Abstract

Introduction

Despite recommendations for COVID-19 primary series completion and booster doses for children and adolescents, coverage has been less than optimal, particularly in some subpopulations. This study explored disparities in childhood/adolescent COVID-19 vaccination, parental intent to vaccinate their children and adolescents, and reasons for non-vaccination in the US.

Methods

Using the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey (HPS), we analyzed households with children aged <18 years using data collected from September 14 to November 14, 2022 (n = 44,929). Child and adolescent COVID-19 vaccination coverage (≥1 dose, completed primary series, and booster vaccination) and parental intentions toward vaccination were assessed by sociodemographic characteristics. Factors associated with child and adolescent vaccination coverage were examined using multivariable regression models. Reasons for non-vaccination were assessed overall, by the child’s age group and respondent’s age group.

Results

Overall, approximately half (50.1%) of children aged < 18 years were vaccinated against COVID-19 (≥1 dose). Completed primary series vaccination was 44.2% among all children aged <18 years. By age group, completed primary series was 13.2% among children <5 years, 43.9% among children 5–11 years, and 63.3% among adolescents 12–17 years. Booster vaccination among those who completed the primary series was 39.1% among children 5–11 years and 55.3% among adolescents 12–17 years. Vaccination coverage differed by race/ethnicity, educational attainment, household income, region, parental COVID-19 vaccination status, prior COVID-19 diagnosis, child’s age group, and parental age group. Parental reluctance was highest for children aged <5 years (46.8%). Main reasons for non-vaccination among reluctant parents were concerns about side effects (53.3%), lack of trust in COVID-19 vaccines (48.7%), and the belief that children do not need a COVID-19 vaccine (38.8%).

Conclusion

Disparities in COVID-19 vaccination coverage among children and adolescents continue to exist. Further efforts are needed to increase COVID-19 primary series and booster vaccination and parental confidence in vaccines.

KEY MESSAGES

Using survey data collected from September 14 to November 14, 2022, COVID-19 vaccination coverage was low among children and adolescents. Overall, approximately half (50.1%) of the children aged <18 years were vaccinated against COVID-19 (≥1 dose). Completed primary series vaccination was 44.2% among all children aged < 18 years. By age group, completed primary series was 13.2% among children <5 years, 43.9% among children 5–11 years, and 63.3% among adolescents 12–17 years. Booster vaccination, among those who completed the primary series, was 39.1% among children 5–11 years and 55.3% among adolescents 12–17 years.

Vaccination coverage differed by race/ethnicity, educational attainment, household income, region, parental COVID-19 vaccination status, prior COVID-19 diagnosis, child’s age group, and parental age group.

Parental reluctance was the highest for children aged <5 years (46.8%), followed by children 5–11 years (35.8%) and adolescents 12–17 years (23.5%).

Main reasons for non-vaccination among reluctant parents were concerns about side effects (53.3%), lack of trust in COVID-19 vaccines (48.7%), the belief that children do not need a COVID-19 vaccine (38.8%), lack of trust in the government (35.6%), and that children in the household were not members of a high-risk group (32.8%).

Disparities in COVID-19 vaccination coverage among children and adolescents continue to exist. Further efforts are needed to increase COVID-19 primary series and booster vaccination and parental confidence in vaccines.

Introduction

COVID-19 vaccines are needed to protect children and adolescents from severe outcomes such as hospitalizations and deaths caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. As of April 2023, children and adolescents under 18 years constituted 17.2% of COVID-19 cases and 2,172 deaths in the U.S [Citation1]. Despite recommendations for COVID-19 primary series completion and booster doses for children and adolescents, coverage has been less than optimal, particularly for young children. COVID-19 vaccination (completed series) was 10.4% among children aged <5 years, 32.9% among children 5–11 years, and 61.8% among adolescents 12–17 years as of April 2023 [Citation2,Citation3]. For COVID-19 booster vaccines, coverage among children is even lower. The CDC reported that only 4.7% of children 5–11 years and 7.7% of adolescents 12–17 years had received the updated bivalent booster vaccine as of April 2023 [Citation3]. Among all age groups, disparities exist in vaccination and parental intention toward vaccination [Citation4–6]. For example, previous studies found that children who were Black or Hispanic, living below the poverty level, or receiving public health insurance were less likely to be vaccinated due to transportation challenges, a lack of access to routine pediatric care, and greater parental vaccine hesitancy [Citation4–6]. Implementing strategic efforts are needed to strengthen vaccination programs and reduce barriers to receiving COVID-19 vaccines.

Because parents are the main decision-makers for child and adolescent vaccination [Citation7], it is important to understand parental characteristics, intentions, and reasons for non-vaccination, so that targeted messages and strategies can be developed to increase vaccination coverage. In general, studies have found increasing child/adolescent vaccination uptake and confidence with increasing parental age [Citation8–12]. However, reasons for the disparities in vaccination coverage by parental age and child/adolescent age are unknown.

The goal of this study was to assess the prevalence of, and factors associated with, child (<5 years, 5–11 years) and adolescent (12–17 years) COVID-19 vaccine coverage (≥1 dose, complete series, and booster dose), parental intent to vaccinate their children and adolescents, and reasons for non-vaccination using a large, nationally representative survey of U.S. households. Examining disparities in child/adolescent vaccination coverage, such as by parental age and other sociodemographic characteristics, parental intent for vaccination, and possible reasons for non-vaccination, is important for developing targeted strategies to increase parents’ confidence and reduce barriers to COVID-19 vaccines.

Methods

Study design

The U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey (HPS) is a nationally representative cross-sectional household survey of adults aged ≥18 years that has been fielded since 2020 to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on U.S. households. The survey design of the HPS has been described previously [Citation13]. Non-institutionalized adults aged ≥18 years in the United States were selected from the Census Bureau’s Master Address File and contacted via email and/or text. The survey was conducted online using Qualtrics as a data collection platform. Data were collected from September 14–28, 2022 (response rate = 4.7%), October 5–17, 2022 (response rate = 3.9%); and November 2–14, 2022 (response rate = 5.6%) [Citation14,Citation15].

This analysis included only respondents (who could be parents, grandparents, aunts/uncles, older siblings, or other family members, but hereafter referred to as ‘parents’ for simplicity) with children aged <18 years living in the household. This study on disparities in COVID-19 vaccination coverage and intent among children and adolescents was reviewed by the Tufts University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board and determined as not human subjects research (Study ID:00003208).

COVID-19 vaccination, intent, and reasons for non-vaccination

To identify households with children, respondents were asked: ‘In your household, are there… Children under 5 years old? Children 5 through 11 years old? Children aged 12–17 years?’ The analyses were restricted to households with children aged 17 years or younger. Among households with children, respondents were asked, ‘Have any of the children living in your household received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine?’ (did not specify the child’s age). To assess primary series completion, respondents were asked ‘Are any of the children (under 5 years old/5–11 years/12–17 years) fully vaccinated against COVID-19?’ To assess booster vaccine uptake, respondents were asked, ‘Have any of the children (under 5 years old/5–11 years/12–17 years) received a booster or additional doses of a COVID-19 vaccine?’ Booster vaccination was assessed among those who completed their primary vaccine series. Vaccination coverage was assessed for all children aged <18 years, as well as by age group. Age-specific analyses were restricted to households that exclusively had children aged <5 years (n = 8,381), 5–11 years (n = 9,169), or 12–17 years (n = 13,533) because the question about whether children received at least one dose did not distinguish between the child age groups. While there were 44,929 households with children aged <18 years, 13,846 households were excluded from age-specific analyses because they had children in multiple age groups, resulting in a total of 31,083 households with only children in each of the age-specific strata (<5, 5–11, 12–17 years).

Among respondents whose children were not vaccinated by the time of the survey, respondents were asked about their intent to vaccinate children: ‘Now that vaccines to prevent COVID-19 are available to most children, will the parents or guardians of children in your household…’ Response options were definitely, probably, be unsure about, probably not, or definitely not get the children a vaccine, or ‘I do not know the plans for vaccination of children living in my household.’ Vaccination intent was categorized as uncertain (probably will/unsure about) or reluctant (probably not/definitely not). Results for those who would definitely get children a vaccine were not included in the tables because sample sizes were very small.

Furthermore, these respondents were asked: ‘Which of the following, if any, are reasons that the parents or guardians of children living in your household may not or will not get a vaccine for all of the children?’ Response options, for which respondents could select all that applied, were: (1) concern about possible side effects of a COVID-19 vaccine for children; (2) plan to wait and see if it is safe and may get it later; (3) not sure if a COVID-19 vaccine will work for children; (4) don’t believe children need a COVID-19 vaccine; (5) the children in this household are not members of a high-risk group; (6) the children’s doctor has not recommended it; (7) don’t trust COVID-19 vaccines; (8) don’t trust the government; and (9) other. Additional response options included the following and were recoded as ‘other’ due to the small number of responses: (1) other people need it more than the children in this household do right now (n = 403), (2) concern about missing work to have the children vaccinated (n = 225), (3) unable to get a COVID-19 vaccine for children in this household (n = 85), (4) parents or guardians in this household do not vaccinate their children (n = 601), (5) concern about the cost of a COVID-19 vaccine (n = 334), and (6) other (n = 1,857).

Independent variables

Sociodemographic factors assessed for parents of children <18 years were respondent age group (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, ≥50 years), sex (male, female), race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic (NH) Black, NH White, NH Asian, NH other/multiracial), highest educational attainment (high school equivalent or less, some college or Associate’s degree, Bachelor’s degree, graduate degree), annual household income (<$35,000, $35,000–49,999, $50,000–74,999, ≥$75,000, did not report), health insurance status (covered, not covered), respondent vaccination status (vaccinated with ≥1 dose, not vaccinated), respondent history of COVID-19 infection (yes, no), and region (Northeast, Midwest, West, South).

Statistical analysis

Sociodemographic characteristics were assessed for parents of all children <18 years. Child and adolescent COVID-19 vaccination coverage (≥1 dose, completed primary series, and booster vaccination) and parental intentions toward COVID-19 vaccination for their children/adolescents were assessed overall, by child/adolescent age group, and by respondent sociodemographic characteristics. Booster vaccination was only assessed for children 5–17 years because boosters were not recommended for children aged <5 years until December 2022. Factors associated with child and adolescent vaccination coverage (≥1 dose, primary series, and booster) were examined using multivariable modified Poisson regression models, resulting in adjusted prevalence ratios. Appropriate weighting was used to ensure standard errors reflected the sampling design [Citation16]. Independent variables in the model included age group, sex, race/ethnicity, educational status, annual household income, insurance status, parental COVID-19 vaccination status, prior parental COVID-19 diagnosis, geographic region, and the number of children in the household (only for analyses with all child/adolescent age groups combined). Parental intent (uncertain/reluctant) was examined overall and by sociodemographic characteristics of children in all age groups (<5, 5–11, and 12–17 years). Reasons for non-vaccination of children and adolescents were assessed overall, by child/adolescent age, and by respondent age. For comparisons, linear regression was used to compare the differences in survey-weighted proportions (treating the proportions as continuous variables, bounded at 0 and 1) of respondents who are reluctant (probably not/definitely not) toward vaccinations for children <5 years and 5–11 years and compared with those who are reluctant toward vaccinations for adolescents 12–17 years. In addition, we also used linear regression to examine differences in reasons for non-vaccination by parental age. All results presented in the text are statistically significant at p < .05. Analyses accounted for the survey design and weights to ensure a representative sample in Stata (version 17.0).

Results

Among households with children, the plurality of households had one child (44.6%, 95% CI: 43.6, 45.5), followed by two children (33.4%, 95% CI: 32.6, 34.2), and three or more children (22.0%, 95% CI: 21.3, 22.8) (). The percentage of households with children ages 12–17 years was 51.1% (95% CI: 50.3, 51.8), with the oldest children aged children 5–11 years being 30.3% (95% CI: 29.5, 31.0), and the oldest children aged <5 years being 18.7% (95% CI: 18.0, 19.3). Approximately three-quarters (74.7%, 95% CI: 73.9, 75.5) of parents were vaccinated against COVID-19 and more than half (56.7%, 95% CI: 55.9, 57.5) had a previous COVID-19 infection.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of parents of children and adolescents <18 years, United States, household Pulse survey, September 14–November 14, 2022.

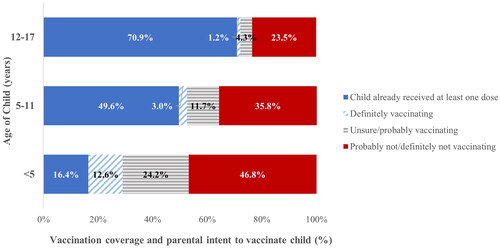

Overall, approximately half (50.1%, 95% CI: 49.2, 50.9) of children aged < 18 years received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine (). COVID-19 vaccination (≥1 dose) was lowest among children aged <5 years (21.2%, 95% CI: 19.9, 22.6), followed by children 5–11 years (49.9%, 95% CI: 47.6, 52.2) and adolescents 12–17 years (69.8%, 95% CI: 68.0, 71.6) (, ). Primary series completion was 44.2% (95% CI: 43.4, 45.1) among all children aged < 18 years (). By age group, primary series completion was 13.2% (95% CI: 12.3, 14.1) among children aged <5 years, 43.9% (95% CI: 41.8, 46.0) among children 5–11 years, and 63.3% (95% CI: 61.3, 65.2) among adolescents 12–17 years. Booster vaccination was 50.3% (95% CI: 48.7, 52.0) among all children 5–17 years; by age group, 39.1% (95% CI: 36.3, 41.9) among children 5–11 years and 55.3% (95% CI: 53.2, 57.4) among adolescents 12–17 years ().

Figure 1. Child/adolescent vaccination coverage (≥ 1 dose) and parental intent to get children vaccinated, by child age/adolescent group, United States, household Pulse Survey, September 14–November 14, 2022.

Table 2. COVID-19 vaccination coverage (≥1 dose) among children and adolescents < 18 yearsTable Footnotea by parental sociodemographic characteristics. United States, Household Pulse Survey, September 14–November 14, 2022.

Table 3. COVID-19 primary series completion among children and adolescents < 18 yearsTable Footnotea by parental sociodemographic characteristics, United States, Household Pulse Survey, September 14–November 14, 2022.

Table 4. COVID-19 booster status among children and adolescents ages 5–17 yearsTable Footnotea,Table Footnoteb by parental sociodemographic characteristics, United States, Household Pulse Survey, September 14–November 14, 2022.

Among households with children aged <18 years, primary series completion was higher among those who were NH Asian (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR] = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.15, 1.28) compared to NH White, those with higher than a college degree (aPR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.30) compared to those with high school diploma or less, those with incomes ≥$75,000 (aPR = 1.17, 95% CI: 1.10, 1.25) compared to those with <$35,000, and those with ≥3 children (aPR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.09, 1.20) compared to those with 1 child in the household. Respondents who had previously had COVID-19 were less likely to vaccinate their children (aPR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.90, 0.96), while those who had received vaccinations themselves were more likely to vaccinate their children (aPR = 9.18, 95% CI: 7.77, 10.84). Those living in the South were less likely to vaccinate their children (aPR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.81, 0.92) compared to those living in the Northeast (). Similar associations were found between demographic characteristics and vaccination uptake (≥1 dose of COVID-19 vaccination, primary series completion, and booster vaccination) for children of all age groups ().

Parental intent to vaccinate children differed by age group and other sociodemographic factors (). Parental uncertainty was highest for children aged <5 years (24.2%, 95% CI: 22.4 26.0), followed by children 5-11 years (11.7%, 95%CI: 10.2, 13.2) and adolescents 12–17 years (4.3%, 95% CI: 3.7, 4.9). Parental reluctance followed the same trend, with it being the highest for children aged <5 years (46.8%, 95% CI: 44.4, 49.2), followed by children 5–11 years (35.8%, 95% CI: 33.8, 37.8) and adolescents 12–17 years (23.5%, 95% CI: 22.0, 25.1). Most parents with children aged <5 years were reluctant to get their children vaccinated if the parents were aged 18–29 years (62.4%, 95% CI: 57.6, 67.1), identified as NH White (52.0%, 95% CI: 49.5, 54.6), had a high school diploma or less (57.7%, 95% CI: 52.3, 63.0), did not report their income (57.4%, 95% CI: 52.9, 61.9), or were not insured (53.0%, 95% CI: 44.4, 61.7). In addition, among parents who had not been vaccinated against COVID-19 and who had children aged <5 years, 90.6% (95% CI: 87.6, 93.6) were reluctant to vaccinate their children. Reluctant parents of children 5–11 years were also similar in terms of age, race/ethnicity, education, income, insurance status, region, and vaccination status. Furthermore, reluctant parents of adolescents 12–17 years were similar with the exception that the highest groups were those aged 30-39 years (35.2%, 95% CI: 30.5, 40.0) and NH other/multiple race (29.3%, 95% CI: 23.1, 35.5).

Table 5. Parental intent to get children vaccinated against COVID-19Table Footnotea by sociodemographic characteristics, United States, Household Pulse Survey, September 14–November 14, 2022.

The main reasons for non-vaccination of children and adolescents among reluctant parents were concerns about side effects (53.3%, 95% CI: 51.7, 54.8), lack of trust in COVID-19 vaccines (48.7%, 95% CI: 47.2, 50.3), the belief that children do not need a COVID-19 vaccine (38.8%, 95% CI: 37.4, 40.1), lack of trust in the government (35.6%, 95% CI: 34.0, 37.3), and belief that children in the household are not members of a high-risk group (32.8%, 95% CI: 31.1, 34.6) (). Reasons for non-vaccination also differed by age group. Among parents of children aged <5 years, the main reasons for non-vaccination among uncertain parents were concerns about side effects (55.1%, 95% CI: 50.5, 59.7) and waiting to see if it was safe and may get it later (52.0%, 95% CI: 47.4, 56.6). Among reluctant parents of children aged <5 years, main barriers to vaccination were concerns about side effects (55.0%, 95% CI: 52.2, 57.9), lack of trust in COVID-19 vaccines (46.1%, 95% CI: 42.5, 49.7), the belief that children do not need a COVID-19 vaccine (41.2%, 95% CI: 38.3, 44.1), the belief that children in the household are not members of a high-risk group (35.5%, 95% CI: 32.3, 38.7), and lack of trust in the government (33.9%, 95% CI: 30.5, 37.3).

Table 6. Reasons for not yet vaccinating child or adolescent against COVID-19,Table Footnotea by child age group and parental intention toward vaccination, United States, Household Pulse Survey, September 14–November 14, 2022.

Reasons for non-vaccination also differed by parental age (). Compared to uncertain parents aged 50 years or older, younger parents were more likely to be concerned about possible side effects (e.g. 61.9% [95% CI: 54.5, 69.2] among parents aged 18–29 years compared to 47.5% [95% CI: 40.6, 54.3] among parents aged 50 years or older), plan to wait to see if it is safe (e.g. 53.7% [95% CI: 46.6, 60.8] among parents aged 18–29 years compared to 33.0% [95% CI: 25.5, 40.4] among parents aged 50 or older), and the belief that children are not members of a high-risk group (e.g. 21.9% [95% CI: 18.6, 25.2] among parents aged 30–39 years compared to 8.3% [95% CI: 5.4, 11.2] among parents aged 50 years or older). Compared to reluctant parents aged 50 years or older, younger parents were more concerned about possible side effects for children (e.g. 56.9% [95% CI: 54.0, 59.8] among parents aged 30–39 compared to 46.2% [95% CI: 42.4, 50.0] among parents aged 50 or older). In addition, other differences in reasons for non-vaccination were planning to wait and see if it is safe (e.g. 20.7% [95% CI: 18.4, 23.1] among parents aged 30–39 years compared to 10.9% [95% CI: 8.5, 13.2] among parents aged 50 years or older), not believing that children need a COVID-19 vaccine (e.g. 42.6% [95% CI: 40.3, 44.9] among parents aged 30–39 years compared to 32.7% [95% CI: 28.9, 36.5] among parents aged 50 years or older), believing that children are not members of a high-risk group (e.g. 37.9% [95% CI: 35.6, 40.1] among parents aged 30–39 years compared to 22.7% [95% CI: 19.8, 25.7] among parents aged 50 years or older), and lack of recommendation from children’s doctors (e.g. 16.2% [95% CI: 14.0, 18.3] among parents aged 30–39 compared to 9.8% [95% CI: 7.6, 12.0] among parents aged 50 years or older).

Table 7. Reasons for not yet vaccinating child or adolescent against COVID-19,Table Footnotea by parental age group and intent, United States, Household Pulse Survey, September 14–November 14, 2022.

Discussion

Uptake of child and adolescent COVID-19 vaccines, particularly for booster doses, has been low for some sociodemographic groups in the U.S. This study found that from September 14–November 14, 2022, COVID-19 vaccination coverage was lowest for children aged <5 years, with 21.2% having received ≥1 dose and 13.2% having completed the primary COVID-19 vaccine series. Booster vaccination coverage was 39.1% for children 5–11 years and 55.3% for adolescents 12–17 years. Further disparities exist by sociodemographic factors, such as parental age group, sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, annual household income, region, number of children in the household, parental COVID-19 vaccination status, and prior COVID-19 diagnosis. Previous studies have shown that disparities in COVID-19 vaccination among children and adolescents existed by sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, region, parental vaccination status, and prior COVID-19 diagnosis [Citation9,Citation12,Citation17]. This study builds on the literature by examining disparities by type of COVID-19 vaccination, child age group, and reasons for non-vaccination by parental age.

While studies have generally shown increasing COVID-19 vaccination with increasing age among adults [Citation9,Citation13,Citation18], interestingly, this study found lower rates of adolescent vaccination coverage among parents aged 30–39 years compared to all other age groups. A possible explanation may be that respondents aged 18–29 years may include parents but also other family members, such as older siblings. While other studies on child immunizations have found that the percentage of respondents who are not parents to be low (<10%) [Citation14], the HPS is a general household survey that is not limited to child immunizations so the percentage of non-parental family members may be higher. Respondents who are 18–29 years old and are older siblings of the children/adolescents discussed in this study may have older parents. As a result, misrepresenting older siblings as younger parents may have biased some of the results found in this study. Parents aged 30–39 years who were reluctant to receive vaccines were most likely to report concerns about side effects, desire to wait and see if it is safe, the belief that children/adolescents do not need a COVID-19 vaccine, the belief that children/adolescents are not members of a high-risk group, and lack of recommendation from the children/adolescents’ doctor.

Ensuring that parents receive information about the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines for their children is important for increasing vaccination confidence and uptake in this population. Studies have shown that motivational interviewing, which occurs when healthcare professionals inform the patient about vaccination while supporting the patient’s decision-making and respecting the patient’s beliefs, has been found to increase mothers’ intention to vaccinate their children [Citation15,Citation19]. Addressing misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines through the dissemination of factual and easy-to-understand information and increasing vaccine trust and accessibility can increase parents’ confidence in vaccines and willingness to vaccinate their children and adolescents against COVID-19 [Citation20]. Furthermore, studies have shown that healthcare provider recommendations increase vaccination rates, particularly for those with the greatest disparities in COVID-19 coverage [Citation21]. These strategies have been shown to reduce the barriers to childhood and adolescent vaccination that parents reported in this study to increase COVID-19 vaccine confidence and uptake.

Consistent with other data sources [Citation3], this study also found low COVID-19 ≥ 1 dose vaccine coverage (21.2%) and high parental reluctance for vaccination for children aged <5 years (46.8%), emphasizing the importance of increasing vaccination in this group. A possible reason for the low vaccination rate among children aged <5 years is that this age group was the last age group to receive vaccine approval and recommendation (June 2022). COVID-19 can cause severe illnesses in children, particularly in those with underlying medical conditions [Citation22]. The CDC reports that 3.7%, or >3.5 million children aged <5 years have been diagnosed with COVID-19, and over 700 deaths due to COVID-19 have been reported since the beginning of the pandemic [Citation1]. During early 2022, when the Omicron variant was predominant, the weekly COVID-19–associated hospitalization rate peaked at 14.5 per 100,000 infants and children aged 0–4 years, which was approximately five times that during Delta predominance [Citation23]. This study found that the main reasons for non-vaccination among reluctant parents of children aged <5 years were concerns about side effects, lack of trust in COVID-19 vaccines, and the belief that children do not need a COVID-19 vaccine. Addressing vaccine misinformation by providing accurate and clear messages about the vaccine and building trust with community members through collaboration with community and religious leaders is necessary to increase vaccination confidence in this population [Citation24]. Furthermore, encouraging healthcare providers to recommend and underscore the importance of vaccination in reducing severe COVID-19 will help increase vaccination uptake [Citation25]. Lastly, messages to remind parents of any missed COVID-19 vaccines or boosters and offering COVID-19 vaccines at every opportunity, including scheduled well-being visits, can help increase vaccine uptake [Citation26]. The CDC found that offering school-located vaccination programs could help remove logistical barriers and improve vaccination uptake. For example, health departments can partner with school districts and community sites to plan vaccination events for children aged 12–17 and 5–11 years in schools, at COVID-19 community partner vaccination clinics, or mobile clinics [Citation24]. Achieving high vaccination coverage for all children and adolescents is needed to slow the spread of COVID-19 and protect the population from severe illnesses.

While the Household Pulse Survey has a robust sample size and has been used in numerous publications, the data may be subject to several limitations. First, although the sampling methods and data weighting were designed to produce nationally representative results, respondents might not be fully representative of the general U.S. adult population [Citation27]. For example, a report found that data from the HPS may overestimate COVID-19 vaccination coverage compared to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker, which is derived from provider-reported vaccine administration data; however, the HPS estimates showed similar patterns in relative coverage by sex, age group, and state compared to the vaccine administration data [Citation28,Citation29]. Furthermore, the purpose of this study was to examine factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination and compare coverage estimates among different subpopulations, and not solely to provide coverage estimates, which could be derived from CDC’s provider-reported vaccination data. Disparities identified using the HPS study has been found to be consistent with those from CDC’s provider-reported vaccination data [Citation30,Citation31]. Second, the vaccination status of respondents and their children/adolescents was self-reported and may have been subject to recall or social desirability bias. Third, the bivalent booster vaccine was recommended for persons 12 years and older on September 1, 2022, after the questions on the HPS had already been finalized for the September 14–November 14, 2022, data collection. As a result, the questions on the booster vaccination were not specific to the updated bivalent booster vaccine and could include any booster or additional doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. Prior to the recommendation of the bivalent booster vaccines, booster vaccination coverage was assessed as the receipt of booster vaccination among those who are eligible (e.g. received primary series) [Citation32–35]. Since our results are likely to contain doses from boosters received prior to September 1, 2022, we analyzed booster vaccination coverage according to the CDC definition at that time (e.g. booster receipt among those who completed the primary series), and this may not reflect or be comparable with the current booster coverage definition, which is the receipt of the bivalent booster vaccine among the U.S. population [Citation3]. Fourth, respondents in this study are adults who reside with children <18 years in the home. While these respondents are likely to be the parents of these children, they could also be grandparents, aunts/uncles, older siblings, or other family members. Respondents who are family members but not parents of the children/adolescents mentioned in this study may have biased some of the results found in this study. Finally, the HPS had a low response rate (<10%), although the non-response bias assessment conducted by the Census Bureau found that the survey weights mitigated most of this bias [Citation36].

Conclusions

This study found disparities in COVID-19 vaccination coverage among children and adolescents by sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, household income, region, parental COVID-19 vaccination status, prior COVID-19 diagnosis, child age group, and parental age group. Approximately one in five children aged <5 years received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, and half of the children 5–17 years received the booster vaccine. Parental age also affects the likelihood of child/adolescent vaccination, with adolescents aged 12–17 years from parents 30–39 years having the lowest vaccination coverage estimates compared with adolescents from parents of other age groups. The main reasons for non-vaccination were concerns about side effects, lack of trust in COVID-19 vaccines, and the belief that vaccines are not needed for children and adolescents. Further efforts are needed to increase COVID-19 primary series and booster vaccination for all children and adolescents and to reduce disparities in uptake and intention to vaccinate. Increased vaccination would not only protect children and adolescents from severe illness or death from COVID-19 but also prevent the spread of COVID-19, particularly if new variants emerge [Citation37].

Author contributions

Kimberly Nguyen was involved in the conception and design of the study, interpretation of the data, drafting of the paper, and critical revision for intellectual content. Cheyenne McChesney was involved in the conception and design, analysis, and interpretation of the data and revising it critically for intellectual content. Ariella Levisohn was involved in the conception and design, analysis, and interpretation of the data and revising it critically for intellectual content. Laura Corlin was involved in the conception and design, supervision of the analysis, interpretation of the data, and critical revision of the intellectual content. Robert Bednarcyzk was involved in the conception and design of the study, interpretation of the data, and critical revision for intellectual content. Vasudevan was involved in the conception and design, interpretation of the data, and critical revision for intellectual content. All authors provided final approval for the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/datasets.html.

Additional information

Funding

References

- CDC. 2023. Demographic trends of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the US reported to CDC. Available from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#demographics.

- CDC. Weekly flu vaccination dashboard. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/dashboard/vaccination-dashboard.html.

- CDC. 2023. COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Available from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations_vacc-total-admin-rate-total.

- Murthy NC, Zell E, Fast HE, et al. Disparities in first dose COVID-19 vaccination coverage among children 5–11 years of age, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28(5):1–15. doi: 10.3201/eid2805.220166.

- Valier MR, Elam-Evans LD, Mu Y, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in COVID-19 vaccination coverage among children and adolescents aged 5-17 years and parental intent to vaccinate their children – national immunization survey-child COVID module, United States, december 2020-September 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(1):1–8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7201a1.

- Santibanez TA, Zhou T, Black CL, et al. Sociodemographic variation in early uptake of COVID-19 vaccine and parental intent and attitudes toward vaccination of children aged 6 months-4 years – United States, July 1–29, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(46):1479–1484. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7146a3.

- Damnjanovic K, Graeber J, Ilic S, et al. Parental decision-making on childhood vaccination. Front Psychol. 2018;9:735. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00735.

- Baumann BM, Rodriguez RM, DeLaroche AM, et al. Factors associated with parental acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination: a multicenter pediatric emergency department cross-sectional analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2022;80(2):130–142. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2022.01.040.

- Nguyen KH, Nguyen K, Mansfield K, et al. Child and adolescent COVID-19 vaccination status and reasons for non-vaccination by parental vaccination status. Public Health. 2022;209:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2022.06.002.

- Guerin RJ, Naeim A, Baxter-King R, et al. Parental intentions to vaccinate children against COVID-19: findings from a U.S. National survey. Vaccine. 2023;41(1):101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.11.001.

- Teasdale CA, Borrell LN, Shen Y, et al. Parental plans to vaccinate children for COVID-19 in New York city. Vaccine. 2021;39(36):5082–5086. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.058.

- Szilagyi PG, Shah MD, Delgado JR, et al. Parents’ intentions and perceptions about COVID-19 vaccination for their children: results from a national survey. Pediatrics. 2021;148(4):e2021052335. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052335.

- Diesel J, Sterrett N, Dasgupta S, et al. COVID-19 vaccination coverage among adults – United States, December 14, 2020–May 22, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(25):922–927. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7025e1.

- Santibanez TA, Nguyen KH, Greby SM, et al. Parental vaccine hesitancy and childhood influenza vaccination. Pediatrics. 2020;146(6):e2020007609. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-007609.

- Gagneur A. Motivational interviewing: a powerful tool to address vaccine hesitancy. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2020;46(4):93–97. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v46i04a06.

- Coutinho LM, Scazufca M, Menezes PR. Methods for estimating prevalence ratios in cross-sectional studies. Rev Saúde Pública. 2008;42(6):992–998. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102008000600003.

- Nguyen KH, Nguyen K, Geddes M, et al. Trends in adolescent COVID-19 vaccination receipt and parental intent to vaccinate their adolescent children, United States, July to october, 2021. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):733–742. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2045034.

- Kriss JL, Hung MC, Srivastav A, et al. COVID-19 vaccination coverage, by race and ethnicity – National immunization survey adult COVID module, United States, December 2020–November 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(23):757–763. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7123a2.

- Allen JD, Matsunaga M, Lim E, et al. Parental decision making regarding COVID-19 vaccines for children under age 5: does decision self-efficacy play a role? Vaccines. 2023;11(2):478. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11020478.

- Allen JD, Fu Q, Nguyen KH, et al. Parents’ willingness to vaccinate children for COVID-19: conspiracy theories, information sources, and perceived responsibility. J Health Commun. 2023;28(1):15–27. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2023.2172107.

- Nguyen KH, Yankey D, Lu PJ, et al. Report of health care provider recommendation for COVID-19 vaccination among adults, by recipient COVID-19 vaccination status and Attitudes – United States, April–September 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(50):1723–1730. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7050a1.

- CDC. 2023. Pediatric data. Available from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#pediatric-data.

- Marks KJ, Whitaker M, Agathis NT, et al. Hospitalization of infants and children aged 0–4 years with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 – COVID-NET, 14 states, march 2020–February 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(11):429–436. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7111e2.

- CDC. 2023. 12 COVID-19 vaccination strategies for your community. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/vaccinate-with-confidence/community.html.

- CDC. Vaccinate with confidence COVID-19 vaccines strategy for adults. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/vaccinate-with-confidence/strategy.html.

- Mekonnen ZA, Gelaye KA, Were MC, et al. Effect of mobile text message reminders on routine childhood vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):154. doi: 10.1186/s13643-019-1054-0.

- Fields JFH-CJ, Tersine A, Sisson J, et al. Design and operation of the 2020 household pulse survey. Washington (DC): U.S. Census Bureau. 2020. Available from: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/technical-documentation/hhp/2020_HPS_Background.pdf.

- Nguyen K, Lu P, Meador S, et al. 2021. Comparison of COVID-19 vaccination coverage estimates from the household pulse survey, omnibus panel surveys, and COVID-19 vaccine administration data. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/adultvaxview/pubs-resources/covid19-coverage-estimates-comparison.html

- Bradley VC, Kuriwaki S, Isakov M, et al. Unrepresentative big surveys significantly overestimated US vaccine uptake. Nature. 2021;600(7890):695–700. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04198-4.

- CDC. 2023. Trends in number of COVID-19 vaccinations in the US. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [cited 2022 June 10]. Available from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-trends.

- Nguyen KH, Anneser E, Toppo A, et al. Disparities in national and state estimates of COVID-19 vaccination receipt and intent to vaccinate by race/ethnicity, income, and age group among adults >/= 18 years, United States. Vaccine. 2022;40(1):107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.040.

- Fast HE, Zell E, Murthy BP, et al. Booster and additional primary dose COVID-19 vaccinations among adults aged >/=65 years – United States, August 13, 2021–November 19, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(50):1735–1739. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7050e2.

- Fast HE, Murthy BP, Zell E, et al. Booster COVID-19 vaccinations among persons aged >/=5 years and second booster COVID-19 vaccinations among persons aged >/=50 Years – United States, august 13, 2021–August 5, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(35):1121–1125. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7135a4.

- Lu PJ, Zhou T, Santibanez TA, et al. COVID-19 bivalent booster vaccination coverage and intent to receive booster vaccination among adolescents and Adults – United States, November–December 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(7):190–198. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7207a5.

- Lu PJ, Srivastav A, Vashist K, et al. COVID-19 booster dose vaccination coverage and factors associated with booster vaccination among adults, United States, March 2022. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29(1):133–140. doi: 10.3201/eid2901.221151.

- Bureau C. 2021. Nonresponse bias report for the 2020 household pulse survey. Available from: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/technical-documentation/hhp/2020_HPS_NR_Bias_Report-final.pdf.

- CDC. 2023. SARS-CoV-2 variant classifications and definitions. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-classifications.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A//www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-info.html.