?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Purposes

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on physical fitness among college women living in China and to explore how fitness changed with different physical conditions.

Methods

We performed repeated measures of BMI, 800 m running and sit-up performance assessment on college women from one university in China pre and post the COVID-19 lockdown. A total of 3658 (age 19.15 ± 1.08 yr.) college women who completed the same assessment pre and post the COVID-19 lockdown were included in the analysis. We analyzed the data using one way ANOVA and paired-samples t-test.

Results

Due to the COVID-19 lockdown, the result shows a significant increase in BMI by 2.91% (95% CI =0.33, 0.40) and a significant decline in 800 m running and sit-up by 7.97% (95% CI =0.69, 0.77) and 4.91% (95% CI = −0.27, −0.19), respectively. College women in the highest quartile level of physical condition (Quartile 4) had more decreases than college women in the lowest quartile level (Quartile 1). Their BMI level was increased by 3.69% and 0.98% in college women in Quartile 4 and Quartile 1, respectively. Their performance of 800 m running was decreased by 9.32% and 7.37% in college women in Quartile 4 and Quartile 1, respectively. Their performance of sit-up was decreased by 13.88% in college women in Quartile 4 while it increased by 10.91% in college women in Quartile 1, respectively.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 lockdown might increase the BMI level and decrease 800 m running and sit-up performance among college women living in China. The decrease for college women in higher quartile level of physical condition (Quartile 4) were more seriously while college women in lower quartile level of physical condition (Quartile 1) were modest.

KEY MESSAGES

This study performed repeated tests on a large sample of 3658 college women before and after the COVID-19 lockdown to estimate the impact of COVID-19 on physical fitness.

The COVID-19 lockdown decreased physical fitness (BMI, 800 m running and sit-up performance) among college women living in China.

College women in higher level of physical condition at baseline were more seriously affected by the COVID-19 lockdown than college women in lower level of physical condition.

1 Introduction

The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a global pandemic by on 11 March 2020 [Citation1]. To contain the spread of the pandemic, strict lockdown and social distancing measures were implemented all over the country in China. Schools and colleges in all provinces closed from mid-Jan 2020 until mid-June 2020 [Citation2,Citation3]. During the school closure and social isolation, students stayed at home and ceased their school-based exercises and outdoor physical education (PE) courses such as running, jumping, basketball, football, tennis, etc. Simultaneously, public sports venues, playgrounds, and parks were closed. Although the school closure and confinement measures during the pandemic were necessary to prevent the pandemic, they probably limited students’ engagement in sufficient physical activity (PA) and exercises, leading to an increase of sedentary behaviour and the number of health disorders [Citation4]. It is questionable if, in the lockdown period, college students would be led to less participation in physical activity and exercises that could contribute to significant physical fitness changes.

It is known that physical activity and exercises are gold health standards and efficient non-pharmacological approaches in many chronic diseases [Citation5]. However, previous studies have shown that nearly 80% of adolescents were insufficiently active before the pandemic all over the world [Citation6]. Meanwhile, more than 77% of adolescents in school failed to meet the physical activity recommendation guideline of WHO [Citation7–9]. The COVID-19 lockdown had further reduced students’ PA levels and adversely affected their physical fitness [Citation10–13]. One study investigated the physical fitness of 264 eighth-grade students living in the United States and found that students increased their body mass index and decreased their physical fitness performance during the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation14]. Moreover, a previous study evaluated the fitness status of 114 high school students living in Croatia and found that the muscular fitness status of students was negatively influenced by the COVID-19 lockdown [Citation15]. Similarly, a decrease of physical fitness performance was also observed in Chinese high school students and college students after the COVID-19 outbreak [Citation16,Citation17]. To make matters worse, the reduction of physical activity and fitness during the pandemic would probably increase the risk of anxiety, depression symptoms, and weight gain and for students [Citation18–20].

To reduce the negative impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on physical fitness among college students, many colleges carried out web-based PE courses for students at home, as conventional outdoor PE courses were unavailable [Citation21,Citation22]. Learning at home has given college students more free time to participate in PA and exercises, however, it probably existed enormous disparities in access to opportunities base on partners, friends, neighbourhood characteristics, and socioeconomic status at home [Citation23,Citation24]. Many students, especially those with low incomes, do not have indoor space, or adequate equipment to make home-based PE courses or exercises [Citation12]. Nevertheless, few studies [Citation21,Citation22] evaluated the effectiveness of web-based PE courses in preventing the negative effects on physical fitness among college students during the COVID-19 lockdown.

However, there were two main gaps that the previous work did not address. To begin with, the reduced PA level might adversely affect physical fitness among students during the COVID-19 lockdown has been proved by previous studies [Citation11,Citation14,Citation15,Citation25], however, to what extent are the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on the physical fitness of college students still unclear. Besides, it has not been established the impact differs for college students with different physical conditions. In addition, in most of the previous studies, the effect of the pandemic on physical fitness was evaluated by self-reported fitness levels [Citation26–28] or tested by small samples of hundreds [Citation14–16]. However, few studies assessed the impact based on objectively repeated measures with the same individual COVID-19 lockdown in pre and post the COVID-19 lockdown among large samples.

Thus, this study aimed to assess the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on physical fitness (BMI, 800 m running and sit-up) among college women living in China. Also, this study would like to explore the differences among college women in different quartile fitness conditions. Thus, the novelty of this study was performing repeated physical fitness tests on a large sample of 3658 college women in 800 m running and sit-up performances before and after the COVID-19 lockdown. It would provide statistical evidence to contrast changes in 800 m running and sit-up performance among college women with different quartile physical fitness baseline due to the COVID-19 lockdown.

2 Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

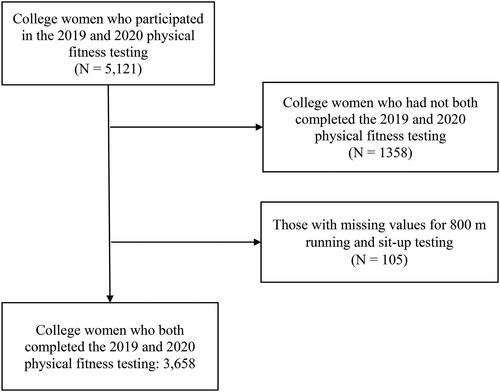

A total of 5121 college women at Tsinghua University participated in the 2019 and 2020 physical fitness testing. 3658 (age 19.16 ± 1.08 yr.) college women both participated and finished the fitness testing in 2019 year (before the COVID-19 lockdown) and 2020 year (after the COVID-19 lockdown). The participants were divided into four groups based on their physical conditions reflected by their 800 m running and sit-up testing performance in 2019. College women who both completed the 800 m running and sit-up testing in the 2019 year and 2020 year were included in this study. shows the analytic sample selection flowchart for the participants in this study.

2.2. Procedures

All college women must take part in physical fitness testing every year except for some special reasons such as disability and illness at Tsinghua University, China. According to the National Student Physical Health Standard (NSPHS) in China [Citation29], the physical fitness assessment for college students contains BMI assessment for both college men and women, while 800 m running and sit-up for college women only. For college women living in China, BMI, 800 m running and sit-up performance assessment were the main measures for evaluating their physical fitness [Citation17,Citation29,Citation30].

Trained teams performed the 800 m running and sit-up testing before and after the COVID-19 lockdown. The lockdown period for the participants in this study was from mid-January 2020 to late August 2020. All of the participants stayed at home during the lockdown and had no access to engaged university-based physical activities. After the lockdown period, the participants went back to school and resumed their university-based physical activities. In this case, the pre-testing in this study was carried out from 9 September to 10 November 2019, and the post-testing in this study was carried out from 19 October to 14 November 2020. The testing was performed from 8:00 am to 12:15 am and 1:30 pm to 6:40 pm. The measurements and procedures of the pre-and-post testing were the same. This study was approved by the Tsinghua University ethics review boards (IRB #2012534001). The study was not a retrospective review, and the data was obtained from college students who participated in physical fitness testing at Tsinghua University pre-and-post the COVID-19 lockdown. Before the testing, trained teams told participants that the testing records, except their personal information, would be used for scientific research. Participants with the agreement would sign the consent. All of the participants included in this study had signed the consent.’ We clarify that informed consent was obtained for participation in the study. The information participants received about the use of their testing data in the research, including their age, height, weight, 800 m running performance, and sit-up performance.

2.3. Measurement

2.3.1. Height & weight

Height & Weight were measured in the fitness assessment room at Tsinghua University. All the college students were barefoot and wore very light clothes. Height was measured by the length from college women’s highest point of their head to their heel without shoes, and weight was measured for college women without shoes and wearing light clothes. The tester used was the Height & Weight tester of Tongfang Health Fitness Testing Products 5000 series (Tongfang Health Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) [Citation31]. This instrument can measure height and weight at the same time. (range: 90–210 cm, considerations: 0.1 cm, precision: ± 0.1%) and (range: 5–150 kg, considerations: 0.1 kg, Precision: ± 0.2%).

2.3.2 800 m Running

The 800 m running testing was carried out on the Tsinghua University playground. The testing was measured by the time of an 800 m race and recorded in seconds. All of the participants warmed up under the guidance of the trained teams before the testing. During the testing, participants were required to wear a vest containing a timing chip that could automatically measure the running time of participants. Participants’ running performance time in the range of 00:00–16:66 (min: sec) would be recorded. Everyone only conducted the 800 m running testing once. The equipment used in this study was the running tester of Tongfang Health Fitness Testing Products 5000 series (Tongfang Health Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) [Citation32].

2.3.3. Sit-Up

The sit-up testing was carried out in the fitness assessment room at Tsinghua University. All of the college women participated in the testing were asked to warm up under the guidance of the trained teams before the sit-up testing. During the testing, the sit-ups were measured by the repetitions of the completed sit-ups of college women. The number of repetitions they performed the sit-ups in one minute would be recorded. Participants were asked to lie flat with their knees bent, feet flat on a mat, hands behind their heads, and fingers crossed. Participants were required to elevate their upper trunk until the elbow touched the thigh and lower their upper trunk until the shoulder blades touched the mat. Everyone was tested only once. The sit-ups in the range of 0–99 repetitions would be recorded and included in this study. The equipment used in this study was the sit-up tester of Tongfang Health Fitness Testing Products 5000 series (Tongfang Health Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) [Citation33].

2.4. Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, and percentiles were used to analyze the basic characteristics of the sample in this study. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the baseline characteristics of college women in four groups (in different physical conditions). Two-way ANOVA was used to compare college women’s mean level of fitness pre-and-post the COVID-19 lockdown by different physical conditions and testing times. Paired sample t-test was used to assess college women’s body mass index (BMI), 800 m running and sit-up performance pre-and-post the COVID-19 lockdown. We performed paired t-test using bootstrapping and stratified, the variables of age and BMI were the covariate. Furthermore, we analyzed the effect size (ES) of Cohen’s d (small ES, 0.2 ≤ d<0.5; medium ES, 0.5≤ d <0.8; large ES, d ≥ 0.8). Finally, the physical fitness changes in 2020 were compared with the 2019 baseline as the reference. For example,

In this study, we also analyzed the differences of fitness change of a subgroup among college women in different physical conditions. We performed visual binning on the variables of BMI, 800 m running and sit-up performance at baseline. We selected BMI, 800 m running and sit-up variables in 2019 whose values will be grouped into bins and divided into four quartiles (Quartile 1, Quartile 2, Quartile 3, and Quartile 4) with a width of 25%. Quartile 1 ranked by participants in the bottom 25% of physical conditions (BMI, 800 m running and sit-up performance at baseline), Quartile 2 ranked by participants in the 25 to 50% group, Quartile 3 ranked by participants in the 50 to 75% group, and Quartile 4 ranked by participants in the top 25% group. The statistical software used in this study was IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). In this study, p < 0.05 was set as the statistical significance level.

3 Results

3.1. The characteristics of participants

describes the baseline characteristics of the sample in 2019 year. The sample were divided into 4 quartiles according to BMI. Participants’ mean age in this study was 19.15 ± 1.08 (years), and participants’s mean age was 19.29 ± 1.13 (years), 19.24 ± 1.16 (years), 19.12 ± 1.08 (years), and 18.97 ± 1.01 (years), respectively. Participants’s mean height in this study was 164.25 ± 5.81 (cm), and participants’ mean height in Quartile 1, Quartile 2, Quartile 3, and Quartile 4 was 163.83 ± 5.89 (cm), 163.85 ± 5.89 (cm), 164.17 ± 5.82 (cm), and 165.16 ± 5.55 (cm), respectively. Participants’s mean weight in this study was 55.86 ± 8.32 (kg), and participants’s mean weight in Quartile 1, Quartile 2, Quartile 3, and Quartile 4 was 65.59 ± 8.34 (kg), 56.62 ± 4.27 (kg), 52.69 ± 3.92 (kg), and 48.54 ± 8.32 (kg), respectively.

Table 1. The baseline characteristics of the sample in 2019 year.

3.2. The physical fitness testing result

shows the descriptive statistics of participants’ physical fitness performance assessment in 2019 (pre the COVID-19 lockdown) and 2020 (post COVID-19 lockdown). Based on the different physical conditions of the participants in the baseline, we performed a two-way ANOVA to examine the physical condition and testing time as factors to assess the interaction between physical conditions (Quartile 1, Quartile 2, Quartile 3, and Quartile 4) and testing time (pre-COVID-19 testing and post-COVID-19 testing).

Table 2. College women’s mean level of fitness pre and post the COVID-19 lockdown by different physical condition.

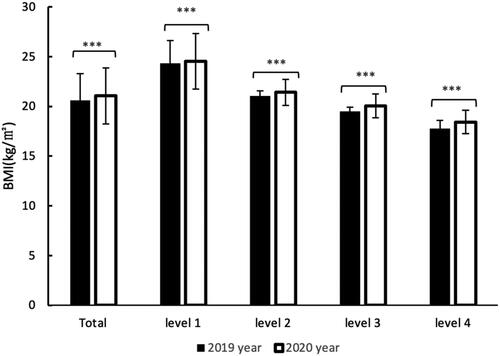

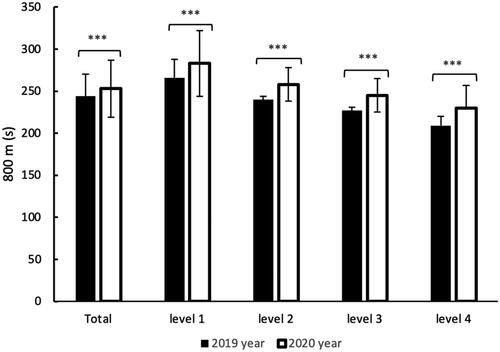

The result showed that the mean level of participants’s BMI in the 2019 and 2020 years were 24.32 ± 2.29 vs. 24.55 ± 2.79 (kg/m2), 21.05 ± 0.50 vs. 21.41 ± 1.30 (kg/m2), 19.52 ± 0.42 vs. 20.05 ± 1.20 (kg/m2), and 17.78 ± 0.81 vs. 18.43 ± 1.17 (kg/m2) for college women in Quartile 1, Quartile 2, Quartile 3, and Quartile 4, respectively. The mean time of participants’s 800 m running in the 2019 and 2020 years were 4:26 ± 0:22 vs. 4:43 ± 0:39 (min:sec), 4:00 ± 0:03 vs. 4:18 ± 0:21 (min:sec), 3:47 ± 0:04 vs. 4:05 ± 0:20 (min:sec), and 3:29 ± 0:11 vs. 3:50 ± 0:27 (min:sec) for college women in Quartile 1, Quartile 2, Quartile 3, and Quartile 4, respectively. The mean repetitions of participants’ sit-up in 2019 and 2020 years were 30.05 ± 5.56 vs. 33.36 ± 10.07 (repetitions), 40.64 ± 2.17 vs. 38.61 ± 8.39 (repetitions), 48.41 ± 1.92 vs. 43.14 ± 8.12 (repetitions), and 54.53 ± 3.66 vs. 46.83 ± 6.87 (repetitions) for college women in Quartile 1, Quartile 2, Quartile 3, and Quartile 4, respectively.

3.3. Impact of COVID-19 on fitness performance

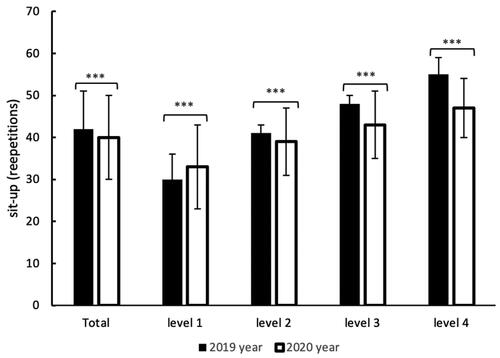

described the paired t-test outcomes for the fitness assessment pre- and- post the COVID-19 lockdown. It is indicated that the college women’s BMI presented a significant increase while 800 m running and sit-up performances presented a significant decline after the lockdown (p<0.001).

Table 3. Paired t-test results of physical fitness testing in 2019 year and 2020 year.

The college women’s BMI increased by 2.91% in total (p<0.001), and the ES was small (d = 0.36). In addition, the BMI increased for college women in Quartile 1, Quartile 2, Quartile 3, and Quartile 4 by 0.98% (p<0.001), 1.73% (p<0.001), 2.72% (p<0.001), and 3.69% (p<0.001), respectively. The ES for college women in Quartile 2 and Quartile 3 was small (d = 0.30, d = 0.47, respectively), and the ES for college women in Quartile 4 was medium (d = 0.69) (see , ).

Figure 2. College women’s mean level of BMI pre and post the COVID-19 lockdown by different physical condition. ***p < 0.001.

The college women’s 800 m running performance decreased by 7.97% in total (p<0.001), and the ES was medium (d = 0.73). In addition, the 800 m running performance decreased for college women in Quartile 1, Quartile 2, Quartile 3, and Quartile 4 by 7.37% (p<0.001), 7.65% (p<0.001), 7.49% (p<0.001), and 9.32% (p<0.001), respectively. The ES for college women in Quartile 2 and Quartile 3 was large (d = 0.90, d = 0.88, respectively), the ES for college women in Quartile 1 and Quartile 4 was medium (d = 0.55, d = 0.77, respectively) (see , ).

Figure 3. College women’s mean level of 800 m running pre and post the COVID-19 lockdown by different physical condition. ***p < 0.001.

The college women’s sit-up performance decreased by 4.91% in total (p<0.001), and the ES was small (d = −0.23). Furthermore, the sit-up performance decreased for college women in Quartile 2, Quartile 3, and Quartile 4 by 5.00%, 10.87%, and 13.88%, respectively. Interestingly, the table showed that sit-up performance of college women in Quartile 1 increased by 10.91%. The ES for college women in Quartile 3 was medium (d = −0.66) and the ES for college women in Quartile 1, Quartile 2 was small (d = 0.33, d=-0.24, respectively). The ES for college women in Quartile 4 was large (d = −1.10) (see , ).

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on the BMI, 800 m running and sit-up performance among college women living in China. It was found that college women’s BMI significantly increased while 800 m running and sit-up performance significantly reduced due to the COVID-19 lockdown. Moreover, this study also found that college women in different physical conditions at baseline were differently affected. The study results showed that college women in Quartile 4, i.e. participants in the highest level of physical condition in the classification, experienced a more significant decline in physical fitness performance. Interestingly, we also found that the college women at Quartile 1, i.e. participants in the lowest level of physical condition in the classification, performed better in sit-up testing after the lockdown.

This study provided statistical evidence to prove the negative impacts of the COVID-19 lockdown on the 800 m running and sit-up performances among college women living in China. It was founded that college women’s BMI increased by 2.91 kg/m2 (p<0.001) in total. This finding was consistent with previous studies reflected that college students gained weight and increased their BMI during the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation34]. Additionally, it was founded that college women’s 800 m running and sit-up performance decreased by 7.97% (p<0.001) and 4.91% (p<0.001) in total, respectively. This finding was consistent with previous studies showing a significant decline in adolescents’ fitness after the COVID-19 lockdown [Citation14,Citation16,Citation35]. Previous study reported the physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour negatively affected the physical fitness of the population during the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation35]. A study investigated 264 adolescents (133 girls) living in the United States and found that the mean level of the participant’s sit-up performance decreased by 19.4% (from 22.7 repetitions to 18.3 repetitions) during the pandemic [Citation14]. A recent study reported that the mean level of 800 m running performance among Chinese students decreased by 9.12% (from 226.9 s to 247.6 s) after the COVID-19 lockdown. However, the study was based on a small sample of only 115 girls [Citation16]. Similarly, previous research proved the negative impact of COVID-19 on 1000 m running and pull-up performance among college men living in China [Citation36], but the study did not take the difference of college men’s physical conditions into consideration.

However, this finding was inconsistent with a study showing no significant change in sit-up performance mean level of college women pre- and- post COVID-19 lockdown [Citation22]. One possible reason for this inconsistency could be that the testing dates of the two studies were different. The previous research carried out the pre-and-post testing in September 2019 and September 2020, respectively. Nevertheless, our study carried out the pre-testing from 9 September to 10 November 2019, and the post-testing from 19 October to 14 November 2020, respectively. In addition, university-based PE courses and college women’s exercise behaviour might take effect in the university in our study. We found that the baseline of college women’s sit-up level in our study was higher than in the previous study (42.41 repetitions vs. 33 repetitions). Even after the lockdown, college women’s sit-up level in our study (39.82 repetitions) was higher than in the previous study (33 repetitions).

Interestingly, we found that the impact of COVID-19 lockdown on college women’s physical fitness varies by their physical condition at baseline. College women in good physical condition at baseline would be more negatively affected by the COVID-19 lockdown. College women in college women in Quartile 4 (the lowest BMI level at baseline) increase their BMI most by 3.69% while Quartile 1 (the highest BMI level at baseline) increase their BMI lest by 0.98%, after the lockdown. Although college women in Quartile 2, Quartile 3, and Quartile 4 significantly declined their 800 m running and sit-up performance, college women in Quartile 1 increased their sit-up performance by 10.91% after the lockdown. One possible explanation for this finding was that college women had different PA and exercise participation before the lockdown, because PA and exercise are positively associated with physical fitness [Citation35]. This study shows that before the lockdown, the sit-up performance of college women in Quartile 1, Quartile 2, Quartile 3, and Quartile 4 were 30.05, 40.64, 48.41, and 54.53 repetitions, respectively. Therefore, we could infer that college women in higher physical condition at baseline were more physically active than others before the COVID-19 lockdown. Thus, college women with a higher level of physical condition at baseline are more likely to be exposed to more negative influences by the COVID-19 lockdown.

Several factors could contribute to the decline in physical fitness of college women living in China. First, school closure and home confinement measures were likely to have a negative impact on most Chinese college students’ psychical activity behaviour during the COVID-19 lockdown, which had been reported by previous research [Citation37,Citation38]. Physical activity behaviour was positively linked with physical fitness [Citation35,Citation39], but the COVID-19 lockdown might lead to a sedentary behaviour. Reduced levels of physical activity would also favour the development of several chronic diseases such as obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and immune system diseases [Citation4,Citation40]. Less chance of physical activity and exercise could contribute to the reduction of college women’s physical fitness during the COVID-19 lockdown. Second, another possible reason for decreasing college women’s physical fitness was that the university-based PE courses had been replaced with web-based PE courses [Citation22]. Although web-based PE courses had some positive influence on the improvement of physical fitness in students, the limited field, equipment, and non-face-to-face classes usually affected the effectiveness of the course compared to outdoor PE courses [Citation22,Citation41]. Thus, web-based PE courses during the lockdown might decrease college women’s exercise volume and intensity and have a negative effect on their physical fitness.

Public health should take the decrease in physical fitness by the COVID-19 lockdown seriously. Previous studies showed that the 800 m running and sit-up performance were associated with cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, respectively [Citation14,Citation30]. The decline in cardiorespiratory fitness is likely to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, and all-cause mortality [Citation42–46]. Similarly, poor performance in muscular fitness was usually associated with cardiovascular disease, cardiometabolic disease, obesity, bone health, and all-cause mortality [Citation43,Citation47–52]. Usually, physically active students have more chance in better physical fitness [Citation53]. However, over the past decade, the physical fitness level of adolescents has decreased significantly worldwide [Citation54], and the COVID-19 lockdown might lead to a more difficult situation for the decline of fitness in adolescents around the world [Citation35]. Thus, the COVID-19 lockdown measures have further amplified the value of PA and exercises that could broadly benefit college women. More attention should be paid to improving Chinese college women’s PA level and exercises after the pandemic.

5. Strength and limitations

The strength of this study is that it performed repeating assessments on the BMI, 800 m running and sit-up performance among college women with a large sample before and after the COVID-19 lockdown. This study used a quasi-experimental study design and made a classification of the subjects depending on their physical condition at baseline. However, some limitations were also existed in this study. Firstly, this study assessed college women’s BMI, 800 m running and sit-up performance at one university in China. Thus, the results of this study cannot be extended to the entire college population in Chinese universities. Further studies should consider replicating the findings in this study at other universities. Secondly, although this study assessed the subjects by BMI, 800 m running and sit-up performance, future studies could provide more specific measures such as the percentage of fat, cardiovascular parameters, blood pressure, heart rate, flexibility to assess physical performance and criteria for more interesting findings.

6. Conclusions

The COVID-19 lockdown decreased the 800 m running and sit-up performance among college women living in China. The impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on college women’s physical fitness varied by their physical condition at baseline. The negative impact seemed serious for the college women in higher quartile level of physical condition at baseline while being modest for those in lower quartile level of physical condition at baseline. After the lockdown, public policies are urgently needed to improve the fitness performance of college women living in China.

Institutional review board statement

This study was approved by the Tsinghua University Institutional Review Board (IRB #2012534001).

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Authors’ contributions

XLF: data analysis, drafting of the paper. XYW: data interpretation, drafting of the paper. YYW: data interpretation, drafting of the paper. LLB: data interpretation, drafting of the paper. HJY: conception and design, data analysis, revising and editing. All authors approved the submitted version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Students Fitness Assessment Centre of Tsinghua University for supporting this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Data availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentially reasons, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020 2020 [cited 2022 July 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19.–11-march-2020.

- UNESCO. Education: from disruption to recovery 2021 [cited 2021 November 30]. Available from: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse.

- Moeprc Moe. Postpones start of 2020 spring semester 2020 [cited 2020 January 29]. Available from: http://en.moe.gov.cn/news/press_releases/202001/t20200130_417069.html.

- De Sousa RAL, Improta-Caria AC, Aras R, et al. Physical exercise effects on the brain during COVID-19 pandemic: links between mental and cardiovascular health. Neurol Sci. 2021;42(4):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05082-9.

- Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Exercise as medicine - evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25:1–72. doi: 10.1111/sms.12581.

- Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, et al. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(1):23–35. doi: 10.1016/s2352-4642(19)30323-2.

- Zhang X, Song Y, Yang T-B, et al. Analysis of current situation of physical activity and influencing factors in Chinese primary and middle school students in 2010. Chin J Prev Medicine. 2012;46(9):781–788.

- WHO. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Switzerland: WHO Press. 2010 [cited 2021 December 16]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241599979.

- Wang Z, Dong Y, Song Y, et al. Analysis on prevalence of physical activity time <1 hour and related factors in students aged 9–22 years in China. Chin J Epidemiol. 2017;38(3):341–345.

- Vainshelboim B, Bopp CM, Wilson OW, et al. Behavioral and physiological health-related risk factors in college students. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;15(3):322–329. doi: 10.1177/1559827619872436.

- Tison GH, Avram R, Kuhar P, et al. Worldwide effect of COVID-19 on physical activity: a descriptive study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(9):767–770. doi: 10.7326/M20-2665.

- Sallis JF, Adlakha D, Oyeyemi A, et al. An international physical activity and public health research agenda to inform coronavirus disease-2019 policies and practices. J Sport Health Sci. 2020;9(4):328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.05.005.

- Dunton GF, Do B, Wang SD. Early effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity and sedentary behavior in children living in the U.S. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1351. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09429-3.

- Wahl-Alexander Z, Camic CL. Impact of COVID-19 on School-Aged male and female health-related fitness markers. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2021;33(2):61–64. doi: 10.1123/pes.2020-0208.

- Sunda M, Gilic B, Peric I, et al. Evidencing the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic and imposed lockdown measures on fitness status in adolescents: a preliminary report. Healthcare. 2021;9(6):681. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9060681.

- Zhou T, Zhai X, Wu N, et al. Changes in physical fitness during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown among adolescents: a longitudinal study. Healthcare. 2022;10(2):351.doi: 10.3390/healthcare10020351.

- Zhao H, Yang XD, Qu FY, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on physical fitness and academic performance of Chinese college students. J Am Coll Health. 2022;70:1–8. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2022.2087472.

- Caputo EL, Reichert FF. Studies of physical activity and COVID-19 during the pandemic: a scoping review. J Phys Act Health. 2020;17(12):1275–1284. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2020-0406.

- Huckins JF, Wang W, Hedlund E, et al. Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6):e20185. doi: 10.2196/20185.

- Zachary Z, Brianna F, Brianna L, et al. Self-quarantine and weight gain related risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2020;14(3):210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2020.05.004.

- Yu J, Jee Y. Analysis of online classes in physical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ Sci. 2020;11(1):3. doi: 10.3390/educsci11010003.

- Xia W, Huang C-h, Guo Y, et al. The physical fitness level of college students before and after web-based physical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:726712. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.726712.

- Quintiliani LM, Bishop HL, Greaney ML, et al. Factors across home, work, and school domains influence nutrition and physical activity behaviors of nontraditional college students. Nutr Res. 2012;32(10):757–763. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2012.09.008.

- Bledniak E, Aleksonis HA, King TZ. The role of tax-filing status in uncovering socioeconomic and physical activity differences in college-aged students. J Am Coll Health. 2021;1:1–10. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2021.1942889.

- Dauty M, Menu P, Fouasson-Chailloux A. Effects of the COVID-19 confinement period on physical conditions in young elite soccer players. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2021;61(9):1252–1257. doi: 10.23736/s0022-4707.20.11669-4.

- Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutr. 2020;12(6):1583. doi: 10.3390/nu12061583.

- Kaur H, Singh T, Arya YK, et al. Physical fitness and exercise during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative enquiry. Front Psychol. 2020;11:2024–2035. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.590172.

- Zenic N, Taiar R, Gilic B, et al. Levels and changes of physical activity in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: contextualizing urban vs. Rural living environment. Appl Sci. 2020;10(11):3997. doi: 10.3390/app10113997.

- MOEPRC. National Student Physical Health Standard. (Revised in 2014) 2014 [cited 2022 April 10]. Available from: http://www.moe.gov.cn/s78/A17/twys_left/moe_938/moe_792/s3273/201407/t20140708_171692.html.

- Gan X, Wen X, Lu Y, et al. Economic growth and cardiorespiratory fitness of children and adolescents in urban areas: a panel data analysis of 27 provinces in China, 1985–2014. IJERPH. 2019;16(19):3772. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16193772.

- TongfangHealth. Height & Weight Tester Beijing2022 [cited 2022 April 27]. Available from: http://www.tfht.com.cn/EN/product-5000-st.php.

- TongfangHealth. Running Tester. 2022 cited 2022 April 27]. Available from: http://www.tfht.com.cn/EN/product-5000-pb.php.

- TongfangHealth. Sit-up Tester 2022 [cited 2022 April 27]. Available from: http://www.tfht.com.cn/EN/product-5000-yw.php.

- Goicochea EA, Coloma-Naldos B, Moya-Salazar J, et al. Physical activity and body image perceived by university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. IJERPH. 2022;19(24):16498. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192416498.

- Pinho CS, Caria ACI, Aras R, et al. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on levels of physical fitness. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2020;66(suppl 2):34–37. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.66.s2.34.

- Feng X, Qiu J, Wang Y, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on 1000 m running and pull-up performance among college men living in China. IJERPH. 2022;19(16):9930. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19169930.

- Xiang M-Q, Tan X-M, Sun J, et al. Relationship of physical activity with anxiety and depression symptoms in Chinese college students during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front Psychol. 2020;11:582436. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.582436.

- Yu H, Song Y, Wang X, et al. The impact of COVID-19 restrictions on physical activity among Chinese University students: a retrospectively matched cohort study. Am J Health Behav. 2022;46(3):294–303. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.46.3.8.

- Wang J. The association between physical fitness and physical activity among Chinese college students. J Am Coll Health. 2019;67(6):602–609. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2018.1515747.

- Improta-Caria AC, Soci UPR, Pinho CS, et al. Physical exercise and immune system: perspectives on the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2021;67(suppl 1):102–107. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.67.suppl1.20200673.

- Lee KJ, Noh B, An KO. Impact of synchronous online physical education classes using tabata training on adolescents during COVID-19: a randomized controlled study. IJERPH. 2021;18(19):10305. PubMed PMID: WOS:000708313800001. doi: 10.3390/ijerph181910305.

- Sawada SS, Lee IM, Naito H, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness, body mass index, and cancer mortality: a cohort study of Japanese men. BMC Pub Heal. 2014;14(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1012.

- Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, Castillo MJ, et al. Physical fitness in childhood and adolescence: a powerful marker of health. Int J Obes. 2008;32(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803774.

- Lee CD, Blair SN. Cardiorespiratory fitness and stroke mortality in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(4):592–595. doi: 10.1249/00005768-200204000-00005.

- Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women. J Am Med Assoc. 2009;301(19):2024–2035. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.681.

- Katzmarzyk PT, Church TS, Janssen I, et al. Metabolic syndrome, obesity, and mortality: impact of cardiorespiratory fitness. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(2):391–397. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.391.

- Smith JJ, Eather N, Morgan PJ, et al. The health benefits of muscular fitness for children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2014;44(9):1209–1223. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0196-4.

- Ortega FB, Silventoinen K, Tynelius P, et al. Muscular strength in male adolescents and premature death: cohort study of one million participants. Br Med J. 2012;345(v20 3):e7279–e7279. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7279.

- Leong DP, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, et al. Prognostic value of grip strength: findings from the prospective urban rural epidemiology (PURE) study. Lancet. 2015;386(9990):266–273. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)62000-6.PubMed PMID: WOS:000358213700031.

- Fraser BJ, Huynh QL, Schmidt MD, et al. Childhood muscular fitness phenotypes and adult metabolic syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(9):1715–1722. doi: 10.1249/mss.0000000000000955.

- Fraser BJ, Blizzard L, Schmidt MD, et al. Childhood cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular fitness and adult measures of glucose homeostasis. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21(9):935–940. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2018.02.002.

- Fraser BJ, Blizzard L, Buscot M-J, et al. The association between grip strength measured in childhood, young- and mid-adulthood and prediabetes or type 2 diabetes in mid-adulthood. Sports Med. 2021;51(1):175–183. doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01328-2.

- Bopp M, Bopp C, Schuchert M. Active transportation to and on campus is associated with objectively measured fitness outcomes among college students. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12(3):418–423. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2013-0332.

- Tomkinson GR, Lang JJ, Tremblay MS. Temporal trends in the cardiorespiratory fitness of children and adolescents representing 19 high-income and upper Middle-income countries between 1981 and 2014. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(8):478–486. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097982.