Abstract

Objective: To compare the anaesthesia methods in percutaneous nephrolithotomy in terms of safety and effectiveness in elderly men.

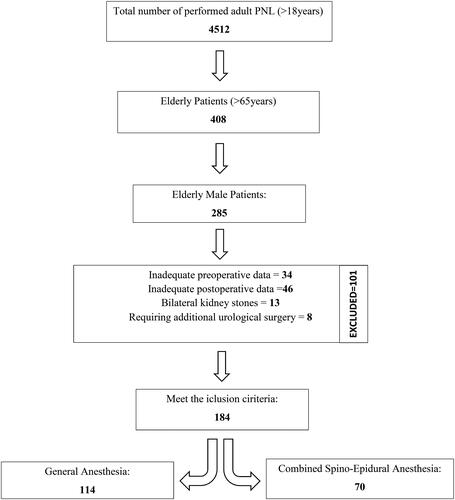

Methods: Elderly male patients who had undergone percutaneous nephrolithotomy were screened retrospectively and divided into 2 groups: percutaneous nephrolithotomy under combined spino-epidural anaesthesia (Group CSEA, n = 70) and percutaneous nephrolithotomy under general anaesthesia (Group GA, n = 114). Preoperative, perioperative and postoperative outcome measures were examined.

Results: Between the two groups, there was no statistically significant difference in terms of stone burden, stone location, presence of the previous operation in the same kidney, presence of staghorn stones, mean American Society of Anesthesiologists scores and presence of abnormal kidney (p > 0.05). The mean duration time in the operation room and post-anaesthesia care unit (PACU) was statistically shorter in the Group CSEA (p < 0.01). There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of Clavien Grade 1 and above complications (p > 0.05). Stone-free rates and success rates were similar in both groups (p = 0.133 and p = 0.273, respectively).

Conclusion: The type of anaesthesia does not affect the success rate and complication rate of percutaneous nephrolithotomy in elderly male patients. Patients who underwent percutaneous nephrolithotomy under CSEA needed less analgesic injection during the postoperative period. CSEA can shorten the time a patient spends in the operating room and PACU, which provides more effective use of operation room working hours.

KEY MESSAGE

Combined spino-epidural anaesthesia (CSEA) can be safely administered in elderly men during PNL operation without affecting surgical success. CSEA patients less occupy the operating rooms. CSEA patients’ postoperative period is more comfortable because of the less painful period.

1. Introduction

The type of anaesthesia that should be employed in percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PNL) has recently intrigued researchers interested in endourology. In the last decade, many studies have been conducted and published on the best type of anaesthesia in PNL, generally covering all age groups [Citation1,Citation2]. However, it is worth noting that these studies have not focused on the elderly population. The anatomy of the kidney, location of kidney stones, size and number of stones, comorbid diseases, and experience of the surgeon are known to affect the success rate of PNL [Citation3]. As the rates of chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, and the use of anticoagulants due to these diseases are higher in elderly patients, an increased risk of anaesthesia for PNL in the elderly seems to be inevitable. However, the type of anaesthesia chosen in PNL is more important in the elderly than in the younger population, especially considering the complications. It has been shown that anaesthesia results can differ, even with gender, due to pharmacokinetic reasons [Citation4]. Previously, it was shown that women are more resistant to general anaesthesia (GA) and wake up earlier than men, and as a result, the time spent in an operating room was significantly shorter for women than for men [Citation5,Citation6]. Thus, studies evaluating the effects of a combination of parameters, such as age, gender and anaesthesia type, on PNL outcomes are needed. In this study, we aimed to compare the outcomes of PNL due to anaesthesia methods in terms of safety and effectiveness in elderly men.

2. Materials and methods

Ethics committee approval for our study was obtained from the ethics committee of Bursa City Hospital with the decision number 2019-KAEK–140 2021-8/4. Our urology unit is one of the largest renal stone centers in Turkey and PNL has been performed in large quantities since 2003. A total of 184 male patients over 65 years of age who had undergone PNL in our unit between 2003 and 2019 were included in this study and analyzed retrospectively. All procedure was performed by surgeons with similar experience, each of whom had performed more than 300 operations. The patients were divided into two groups: PNL under combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia (CSEA) (n = 70) and PNL under GA (n = 114). Patients with inadequate preoperative and postoperative data and with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score above III, with bilateral kidney stones, and conditions requiring additional urological surgery such as ureteroscopy and retrograde intrarenal surgery were excluded.

Preoperative patient history, detailed physical examination, complete blood count, biochemistry tests, urinalysis and culture were performed. All patients underwent preoperative kidney-ureter-bladder radiography (KUBR) and unenhanced spiral computed tomography (SCT). The stone surface area was calculated using the formula “length × width × 0.25 × π”. Preoperative data of age, gender, surgical history for renal stones, stone characteristics, stone area, stone location, presence of hydronephrosis, Guy’s stone score and intraoperative data, such as access number, operation time, and type of anaesthesia, Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score were screened from hospital database records.

2.1. General anaesthesia

In GA endotracheal intubation was performed following intravenous administration of 1 mg/kg lidocaine, 2 mg/kg propofol, 1.5 mcg/kg fentanyl, 0.6 mg/kg rocuronium. Rocuronium and fentanyl maintenance was administered to the patient every 45 min throughout the operation. 1 gr paracetamol and 100 mg tramadol before extubation was done routinely.

Postoperative pain control in Group GA was provided by the intramuscular injection of diclofenac sodium (150 mg/day) or meperidine (200 mg/day) in cases where the VAS score was > 4, until the patients could take the diclofenac sodium personally.

2.2. Combined spino-epidural anaesthesia

The epidural catheter was introduced through an 18 G needle in the intervertebral space at the T12-L1 level to produce sensorial anaesthesia between the T6 segment and the S4 segment (from the kidney to the penile urethra) outside the operating room. A test dose (3 ml of lidocaine with adrenaline at 1:200.000) was administrated. The subarachnoid space was accessed through L3-4 or L4-5 intervertebral space midline by 25 G Quincke spinal needle and 0.125% bupivacaine 3 mL and 20 µg intrathecal fentanyl were administered when cerebrospinal fluid leakage was observed. Subsequently, a 20 mL serum saline mixed solution containing 5 mg of 0.5% bupivacaine and 0.05 mg fentanyl per mL was injected through the epidural catheter. After 15–20 min, the patients were transferred to the operating room under sensorial anaesthesia. Maintenance of anaesthesia was supplied by the injection of the same solution in the amount of 10 mL per 90 min. By the administration of the solution in this concentration, only sensorial anaesthesia was established (without a motor block). Sedation of patients was achieved by intravenous administration of 50 μg of fentanyl or 0.01 mg/kg of diazepam, if necessary.

Postoperative pain control was provided by injection of a 15–20 mL solution containing 3 mg of 0.05% bupivacaine and 0.05 mg of fentanyl in each milliliter through the epidural catheter when the VAS score was >4 (minimum interval of 120 min) in Group CSEA.

2.3. Surgical technique

At the lithotomy position, a 6 French (F) ureteral catheter was inserted through the renal unit by using cystoscopy. After taking the prone position, a renal collecting system was visualized with retrograde pyelography, and an access tract was achieved under fluoroscopy guidance. All procedures, including renal access, were performed by a urologist. After sequential Amplatz dilatation, a 30 F sheath was positioned through the collecting system. In the stone fragmentation process, pneumatic lithotripsy was used as energy. Fragments were extracted using a stone basket or stone grasper. Clearance of the stone fragments was assessed with fluoroscopy. At the end of these procedures, a re-entry nephrostomy catheter was placed, and antegrade pyelography was performed to check for extravasation and colonic injury. For all patients, KUBR was performed on the first postoperative day.

Length of hospital stay, duration of nephrostomy, perioperative and postoperative complications, stone-free (SF) rate, clinically insignificant residual fragment (CIRF) rate, a success rate of an operation and postoperative 4th week glomerular filtration rate (GFR) according to the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula (CKD-EPI) were noted [Citation7].

For the determination of stone clearance, KUBR and UUSG were performed for the patients in the postoperative 4th week. The patients without any residual fragments were described as SF. The presence of residual fragments larger than 4 mm was defined as unsuccessful. CIRFs were defined as fragments ≤ 4 mm, which were non-obstructing, non-infectious and asymptomatic. The operation was defined as successful if the patients had no residual fragments or CIRFs. PNL-associated complications were classified according to the Modified Clavien Classification [Citation8,Citation9].

2.4. Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS version 19 (Chicago, IL, USA) was employed to analyze the data. Continuous variables were given as mean ± standard deviation or median (min-max), while categorical variables were given as numbers and percentages. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was conducted to assess the distribution of data. The student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U tests were performed to compare the two groups. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were conducted for the qualitative data. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

The mean age of all patients (n = 184) was 69.13 ± 3.75 years. Of these patients, 39 (21.2%) patients had undergone previous renal stone surgery, 9 (4.9%) patients had solitary kidneys, 4 (2.2%) patients had horseshoe kidneys, and 25 (13.6%) patients had staghorn renal stones. According to the classification of the ASA, 27 (29%) patients were classified as ASA I, 109 (59.5%) patients were classified as ASA II, and 21 (11.5%) patients were classified as ASA III. Between the Group CSEA and Group GA, there was no statistically significant difference in terms of age, laterality, preoperative laboratory findings, stone burden, stone location, presence of hydronephrosis, presence of the previous operation in the same kidney, presence of staghorn stones, mean ASA scores or presence of abnormal kidney (p > 0.05). In addition, there was no significant difference between the two groups according to access number, presence of upper calyx access, mean operation time, mean fluoroscopy time, mean duration of nephrostomy and mean duration of hospitalization. The mean duration time in the operating room and post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) in the Group CSEA was statistically shorter (p < 0.01) ().

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and clinical features of the groups.

There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of Clavien Grade 1 and the above-mentioned complications (). No complications were observed while inserting the Group CSEA catheter or placing the Group GA tube. Nausea and vomiting associated with CSEA were observed in two patients, and hypotension was seen in one patient. Two patients who could not tolerate pain related to PNL under CSEA were switched to GA.

Table 2. Complications according to Clavien Classification.

SF, CIRF and success rates were similar in both groups (p = 0.133, p = 0.316 and p = 0.273, respectively). Additional shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) was performed in two of six patients who did not benefit from PNL treatment during their 4-week follow-up ().

Table 3. Comparison of regional and general anaesthesia groups according to the surgical outcomes of PNL.

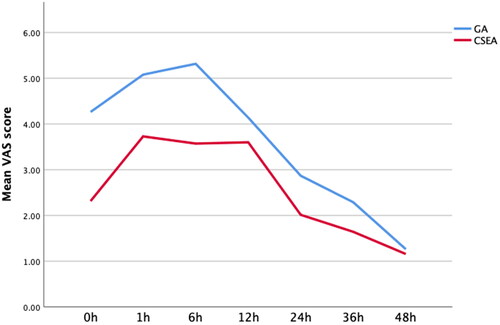

On the postoperative two days, although parenteral analgesics were used in Group GA, they were not needed in Group CSEA (p < 0.001). When the VAS scores of the two groups were compared it was seen that the patients in the CSEA group showed statistically less pain according to the mean VAS score and at hours 0, 1, 6, 24 and 36 (p < 0.001) (, ).

Figure 2. Changes in the post-operative VAS scores GA: General anesthesia, CSEA: Combined spino-epidural anesthesia; h: hour.

Table 4. Comparison of regional and general anaesthesia groups according to the VAS score values.

4. Discussion

In this study, it was found that the effect of anaesthesia type on PNL success rates and complication rates were similar in elderly male patients, but the duration of stay in the operating room and in PACU was shorter in patients who underwent PNL under CSEA compared to PNL under GA.

Although there are many techniques to remove kidney stones, PNL is the most preferred modality in the treatment of large and complex stones. However, the low cardiac and pulmonary reserve due to the natural process of ageing and the high tendency to bleed cause a proneness to complications due to PNL in the elderly population [Citation10]. In contrast, the decline in the GFR with renal parenchymal changes also increases the requirement for stone removal in the elderly population [Citation11,Citation12]. Under these conditions, clinicians should choose the most appropriate case management among alternatives that include watchful waiting or various stone removal techniques, especially for the elderly. Another issue to be decided is the selection of the anaesthesia type in case an operation is planned. Excessive fluid use causes an increased risk of hypothermia, which may cause vasoconstriction and delay the excretion of the agents applied in GA [Citation13]. As a result, the elimination of the drugs administered during anaesthesia induction becomes more difficult. Additionally, the patients who undergo GA are more likely to suffer severe complications, such as drug-induced anaphylaxis, atelectasis, aspiration, exacerbation of existing lung disease, endotracheal tube displacement during a change in the position from lithotomy to prone and dental trauma, than those who undergo regional anaesthesia (RA) [Citation14–16]. Therefore, RA, which does not require the use of general anaesthetic agents, will be a suitable alternative for elderly patients in the presence of comorbid conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular diseases, and a higher stone burden [Citation14,Citation17,Citation18]. According to our study findings, a shorter stay in the operating room and PACU in elderly patients who undergo PNL under CSEA than GA may be associated with less exposure to general anaesthetics and less excessive fluid use in CSEA.

Many studies compare the efficacy and safety of PNL between the younger population and the elderly population. It was shown that PNL in the elderly is as effective and safe as that in the younger population [Citation19–21]. On the other hand, the number of studies evaluating the results of PNL and its relationship with anaesthesia type in elderly male or female patients is limited. In a recent study by Besiroglu et al. (2020), in accordance with the literature, PNL under GA in aging males (over 40 years of age) was described as beneficial and safe as that for younger patients [Citation22]. In this study, we evaluated the effect of anaesthesia type on the outcomes of PNL in elderly male patients; no statistically significant difference was found in terms of success rates (p = 0.273) and complication rates (p = 0.460) between the two groups according to anaesthesia types.

A common finding of the studies that evaluate the efficacy of the anaesthesia method (GA versus CSEA) on the outcome of PNL in the general population is that the anaesthesia type does not affect the outcomes of PNL [Citation23–25]. Singh et al. (2011) stated that verbal commands can be given to patients in PNL under CSEA, which is especially advantageous to avoid pulmonary complications while performing high supracostal access [Citation24]. Oner et al. (2018) reported a similar situation in their studies and that patients who underwent PNL under CSEA spent less time in the operating room. The authors attributed this observation to the lack of recovery time in CSEA unlike GA [Citation25]. In the current study, we found that duration time in the operating room was significantly shorter in the Group CSEA than the Group GA in elderly male patients, similar to the findings of the younger population (<0.001). Although postoperative complications and success rates after PNL in elderly patients do not change with the type of anaesthesia, we consider that a shorter stay in the operating room for the patient who underwent PNL under CSEA will be an important factor in terms of surgical comfort and patient’s preference of anaesthesia type.

Postoperative pain secondary to PNL is another important issue to address. Mehrabi et al. (2013) showed that the need for opioid analgesia on the postoperative first day after PNL was less in Group CSEA compared to Group GA [Citation26]. Singh and Oner also noted in their studies that groups who underwent RA needed fewer analgesic agents than GA in the postoperative period [Citation23,Citation25]. In accordance with the previous results, the postoperative analgesic requirement was significantly lower in the Group CSEA in our study (p < 0.001).

Karacalar et al. (2009) showed in their prospective study that CSEA was associated with superiorities, such as a shorter stay in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU), shorter hospital stay, better postoperative pain management and more patient satisfaction [Citation27]. Kati et al. found that using irrigation fluid at body temperature could result in a faster awakening from anaesthesia [Citation28]. According to our results, while the time spent in PACU was significantly shorter in the Group CSEA (p < 0.001), there was no difference in terms of the duration of hospital stay according to anaesthesia type in the elderly (p = 0.835). Considering factors such as the presence of comorbid chronic diseases and age-related delay in wound healing in the elderly, the shorter duration of stay in the PACU in PNL performed under CSEA can be considered an important sign of the superiority of CSEA in terms of anaesthesia preference in elderly men.

The strongest aspect of our study is that it examines in detail the effects of anaesthesia type on PNL outcomes in a population of satisfactory size with elderly men over 65 years of age. However, there are some limitations to this study. First, the study is not prospectively designed, therefore, only the variables available in hospital records could be evaluated. Second, the groups could not be randomized, and there is no control group. Last, anaesthesia interventions were sometimes performed by different anesthesiologists, which is considered to be an important factor in preventing the standardization of results.

5. Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first study to investigate the effect of anesthesia type on PNL results only in elderly male patients. According to our findings, the type of anesthesia does not affect the success rates and complication rates of PNL in the elderly. Patients who underwent PNL under CSEA needed less analgesic injection during the postoperative period. In addition, PNL under CSEA has been found to allow patients to stay in the operating room and PACU for a shorter period of time. PNL performed under CSEA is an effective and safe method, may be a priority in terms of anesthesia preference in elderly patients, and may enable more effective use of operating room working hours.

Author contributions

SO and EO conceived of and designed the manuscript; VC, MK, SA and AE contributed to interpreting data, drafting the manuscript, critically revising the manuscript for intellectual content, ST applied the patients’ anesthesia procedure; all authors approved of the published version.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

This research data is available on request from the authors. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Sedat Oner, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Basiri A, Kashi AH, Zeinali M, et al. Limitations of spinal anesthesia for patient and surgeon during percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urol J. 2018;15(4):1–8.

- Solakhan M, Bulut E, Erturhan MS. Comparison of two different anesthesia methods in patients undergoing percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urol J. 2019;16(3):246–250.

- Michel MS, Trojan L, Rassweiler JJ. Complications in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Eur Urol. 2007;51(4):899–906; discussion 906. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.10.020.

- Hoymork SC, Raeder J. Why do women wake up faster than men from propofol anaesthesia? Br J Anaesth. 2005;95(5):627–633. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei245.

- Gan TJ, Glass PS, Sigl J, et al. Women emerge from general anesthesia with propofol/alfentanil/nitrous oxide faster than men. Anesthesiology. 1999;90(5):1283–1287. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199905000-00010.

- Kodaka M, Suzuki T, Maeyama A, et al. Gender differences between predicted and measured propofol Cp50 for loss of consciousness. J Clin Anesth. 2006;18(7):486–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2006.08.004.

- Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006.

- De la Rosette JJ, Zuazu JR, Tsakiris P, et al. Prognostic factors and percutaneous nephrolithotomy morbidity: a multivariate analysis of a contemporary series using the clavien classification. J Urol. 2008;180(6):2489–2493. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.08.025.

- Tefekli A, Ali Karadag M, Tepeler K, et al. Classification of percutaneous nephrolithotomy complications using the modified clavien grading system: looking for a standard. Eur Urol. 2008;53(1):184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.06.049.

- Tonner PH, Kampen J, Scholz J. Pathophysiological changes in the elderly. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2003;17(2):163–177. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6896(03)00010-7.

- Gillen DL, Worcester EM, Coe FL. Decreased renal function among adults with a history of nephrolithiasis: a study of NHANES III. Kidney Int. 2005;67(2):685–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67128.x.

- Worcester EM, Parks JH, Evan AP, et al. Renal function in patients with nephrolithiasis. J Urol. 2006;176(2):600–603; discussion 603. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.03.095.

- McSwain JR, Yared M, Doty JW, et al. Perioperative hypothermia: causes, consequences and treatment. WJA. 2015;4(3):58–65. doi: 10.5313/wja.v4.i3.58.

- Rozentsveig V, Neulander EZ, Roussabrov E, et al. Anesthetic considerations during percutaneous nephrolithotomy. J Clin Anesth. 2007;19(5):351–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2007.02.010.

- Smetana GW. Preoperative pulmonary evaluation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(12):937–944. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903253401207.

- Newland MC, Ellis SJ, Peters KR, et al. Dental injury associated with anesthesia: a report of 161,687 anesthetics given over 14 years. J Clin Anesth. 2007;19(5):339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2007.02.007.

- Mehrabi S, Shirazi K. K. Results and complications of spinal anesthesia in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urol J. 2010;7(1):22–25.

- El-Husseiny T, Moraitis K, Maan Z, et al. Percutaneous endourologic procedures in high-risk patients in the lateral decubitus position under regional anesthesia. J Endourol. 2009;23(10):1603–1606. doi: 10.1089/end.2009.1525.

- Okeke Z, Smith AD, Labate G, et al. Prospective comparison of outcomes of percutaneous nephrolithotomy in elderly patients versus younger patients. J Endourol. 2012;26(8):996–1001. doi: 10.1089/end.2012.0046.

- Sahin A, Atsü N, Erdem E, et al. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy in patients aged 60 years or older. J Endourol. 2001;15(5):489–491. doi: 10.1089/089277901750299276.

- Stoller ML, Bolton D, St Lezin M, et al. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy in the elderly. Urology. 1994;44(5):651–654. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(94)80198-3.

- Besiroglu H, Merder E, Dedekarginoglu G. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy is safe and effective in aging male patients: a single center experience. Aging Male. 2020;23(5):705–710. doi: 10.1080/13685538.2019.1581756.

- Singh V, Sinha RJ, Sankhwar SN, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing percutaneous nephrolithotomy under combined spinal-epidural anesthesia with percutaneous nephrolithotomy under general anesthesia. Urol Int. 2011;87(3):293–298. doi: 10.1159/000329796.

- Nouralizadeh A, Ziaee SA, Hosseini Sharifi SH, et al. Comparison of percutaneous nephrolithotomy under spinal versus general anesthesia: a randomized clinical trial. J Endourol. 2013;27(8):974–978. doi: 10.1089/end.2013.0145.

- Oner S, Acar B, Onen E, et al. Comparison of epidural anesthesia without motor block versus general anesthesia for percutaneous nephrolithotomy. jus. 2018;5(3):143–148. doi: 10.4274/jus.1866.

- Mehrabi S, Mousavi Zadeh A, Akbartabar Toori M, et al. General versus spinal anesthesia in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urol J. 2013;10(1):756–761.

- Karacalar S, Bilen CY, Sarihasan B, et al. Spinal-epidural anesthesia versus general anesthesia in the management of percutaneous nephrolithotripsy. J Endourol. 2009;23(10):1591–1597. doi: 10.1089/end.2009.0224.

- Kati B, Buyukfirat E, Pelit ES, et al. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy with different temperature irrigation and effects on surgical complications and anesthesiology applications. J Endourol. 2018;32(11):1050–1053. doi: 10.1089/end.2018.0581.