Abstract

Introduction

Studying post-vaccination side effects and identifying the reasons behind low vaccine uptake are pivotal for overcoming the pandemic.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was distributed through social media platforms and face-to-face interviews. Data from vaccinated and unvaccinated participants were collected and analyzed using the chi-square test, multivariable logistic regression to detect factors associated with side effects and severe side effects.

Results

Of the 3509 participants included, 1672(47.6%) were vaccinated. The most common reason for not taking the vaccine was concerns about the vaccine’s side effects 815(44.4). The majority of symptoms were mild 788(47.1%), followed by moderate 374(22.3%), and severe 144(8.6%). The most common symptoms were tiredness 1028(61.5%), pain at the injection site 933(55.8%), and low-grade fever 684(40.9%). Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that <40 years (vs. ≥40; OR: 2.113, p-value = 0.008), females (vs. males; OR: 2.245, p-value< .001), did not receive influenza shot last year (vs. did receive Influenza shot last year OR: 1.697, p-value = 0.041), AstraZeneca (vs. other vaccine brands; OR: 2.799, p-value< .001), co-morbidities (vs. no co-morbidities; OR: 1.993, p-value = 0.008), and diabetes mellitus (vs. no diabetes mellitus; OR: 2.788, p-value = 0.007) were associated with severe post-vaccine side effects. Serious side effects reported were blood clots 5(0.3%), thrombocytopenia 2(0.1%), anaphylaxis 1(0.1%), seizures 1(0.1%), and cardiac infarction 1(0.1%).

Conclusion

Our study revealed that most side effects reported were mild in severity and self-limiting. Increasing the public’s awareness of the nature of the vaccine’s side effects would reduce the misinformation and improve the public’s trust in vaccines. Larger studies to evaluate rare and serious adverse events and long-term side effects are needed, so people can have sufficient information and understanding before making an informed consent which is essential for vaccination.

KEY MESSAGES

Age < 40 years, females, not receiving influenza shot, AstraZeneca vaccine, co-morbidities, and diabetes mellitus were factors significantly associated with severe post-vaccination side effects.

Although most of the reported vaccine side effects were mild in severity and well-tolerated, larger prospective studies to understand the causes of rare serious adverse events and long-term side effects are needed to overcome vaccine hesitancy among people and enable them to have sufficient information and understanding before making an informed consent which is essential for vaccination.

Introduction

On 11 March 2020, the novel Coronavirus disease of 2019 (Covid-19) was announced a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), only four months after the first known case of Covid-19, reported in China [Citation1]. The pandemic spread has been rapid and heterogeneous causing one of the greatest global humanitarian crises in recorded history.

The vigilance around personal protective measures including wearing face masks, maintaining interpersonal 2-meter distance, avoiding mass gatherings, washing hands, and quarantine have slowly eased off. Although such measures might have mitigated the spread and thus saved lives, sustaining these measures in the long term must be balanced against the various health, social, and economic aspects [Citation2]. Therefore, vaccines remain the only solution for this never-ending crisis, triggering a massive global effort [Citation3], as leading pharmaceutical companies and scientists were in a race against time to develop and test the first effective vaccine. Several vaccines have been approved for emergency or full use by WHO: Pfizer–BioNTech, Oxford–AstraZeneca, Sinopharm BIBP, Moderna, Janssen, CoronaVac, Covaxin, Novavax, and Convidecia. Other vaccines are under assessment by the WHO: Sputnik V, Sinopharm WIBP, Abdala, Zifivax, Corbevax, V, COVIran Barekat, Sanofi–GSK, and SCB-2019 [Citation4]. Immunization with the currently approved vaccines remains the only way to protect oneself against COVID-19, especially when there is no clear global consensus on the treatment guidinclusionnes for Covid-19.

Today 2.7 billion people have yet to receive their first vaccine dose against Covid-19 [Citation5]. Most of the unvaccinated live in lower-middle-income and low-income countries [Citation5]. In Syria, only 9.3% of the population is fully vaccinated [Citation6], despite the total number of vaccines delivered to Syria by the Covid-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) being sufficient to cover 39% of the population [Citation7]. Syria received its first batch of Covid-19 vaccines on 21April 2021, delivered by COVAX [Citation8]. The WHO supported the operating costs of vaccine administration, and vaccines are now available in 962 fixed sites: 39 hospitals, and 923 primary healthcare centres [Citation7]. The vaccines currently available in Syria are Pfizer–BioNTech, AstraZeneca, Sinopharm, Moderna, Janssen, Sputnick light, Sputnick v, and Sinovac.

Although the efficacy and safety of the approved vaccines have been shown to be promising by many prestigious organizations [Citation9,Citation10], information on the long-term side effects and safety in literature remains scant. Headache, fever, fatigue, and pain at the site of injection were the most abundantly reported side effects of the Covid-19 vaccine, with the side effect severity ranging between mild and moderate [Citation11,Citation12,Citation13]. Serious vaccine complications, despite the rarity, include blood clots after the first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine [Citation11]. This dangerous complication has negatively impacted the acceptance of vaccines and disseminated fear of Covid-19 vaccines. Despite Covid-19 infecting over half a billion and killing millions [Citation14], the public’s lost confidence in vaccines safety and efficacy remains the main reason behind low vaccination rates [Citation15,Citation16]. The culprit, social media is negatively affecting the users’ views and intentions to enrol in the uptake of the vaccine [Citation17,Citation18]. For these reasons, post-vaccination surveillance of the vaccines’ side effects and reasons behind the stigma of vaccines has become an area of interest.

Our study aims to assess Covid-19 vaccine uptake, self-reported vaccine side effects and the reasons for not taking the vaccine among Syrians more than a year after the introduction of vaccines in Syria. The objectives of this study are to identify factors associated with Covid-19 vaccine side effects and severe side effects.

Methods

Study design and instrument

A cross-sectional study was carried out between 13 April 28 and May 2022, using convenience sampling strategy. A literature review was conducted to find related research on the topic of the study using relevant keywords (Covid-19 vaccines, side effects, Syria, and worldwide). After an extensive review, the survey was created by the authors according to the information published by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Citation19]. We piloted the questionnaire to assess the clarity, acceptability, and relevance of the survey on 30 volunteers. These volunteers were happy with the questionnaire and were excluded from the final sample to avoid bias. The survey was displayed using Google Forms and distributed by the data collection group through social media apps (Facebook, Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram). To lower non-response bias, graphics interchange format (GIF) and posts were adapted to appeal to each social group. The questions were short multiple choice questions that required no typing. Authors interacted with the participants online and viewers were allowed to comment on the link to increase the survey’s popularity. Face-to-face interviews were also conducted with people in hospitals and on the streets. The inclusion criteria for this study were: Syrian citizens (residing in Syria or a Syrian who took the vaccine outside Syria), aged ≥ 16 years, willing to participate in the study, willing to complete the survey, and willing to provide informed consent. All other respondents not fulfilling the eligibility criteria were excluded from the study. Inability of the participants to complete any section or give contradictory answers rendered the response as incomplete and was then removed from the statistical analysis during validation of the responses. The time needed to complete the survey was 5 min. A brief description of the study was given before the participants and/or their legal guardian(s) provided informed consent. All participants were informed that their responses will remain confidential and will only be used for scientific purposes. The survey included three parts, the first part contained questions on demographic features including age, gender, health status, history of known allergy, history of seasonal influenza shot, smoking history, and history of Covid-19 infection. Confirmation of Covid-19 infection by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was not required in this question. Previous studies found that self-reporting of Covid-19 related symptoms are adequate predictors of Covid-19 infection [Citation20,Citation21]. The second part had two options depending on whether the participant was vaccinated or not. Participants that did not take the vaccine were only asked for the reasons behind this, and then the survey would automatically end. For those that did take the vaccine, information gathered included the vaccine brand, number of doses received (Sputnik light, and Johnson and Johnson are single dose vaccines), vaccination dates, self-reported side effects post-vaccination, symptom severity (self-rated with the options mild, moderate, and severe), onset of symptoms, duration of symptoms, use of painkillers, need for medical assistance, serious adverse events, and history and date of post-vaccination Covid-19 infection. We also asked the participants about the symptoms that lasted more than two weeks post-vaccination. A sample size calculator (website: https://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm) was used to calculate the sample size of 2401 participants based on a confidence interval of 2%, and a confidence level of 95%, for a population of 18284423.

Statistical analysis

The data was collected via Google Forms and were analyzed by entering the data in the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) software version 25. Descriptive statistics were used to express the socio-demographic features of the study sample. Pearson Chi-Square test was performed to evaluate the association between categorical variables. All p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. A multivariable logistic regression model was carried out to detect factors associated with side effects (vs. no side effects), the selected factors included age (<40 vs ≥40), gender (females vs males), smoking history (smoker vs non-smoker), occupation (healthcare worker vs non healthcare worker), seasonal influenza shot (received it vs did not receive it), vaccine brand (Oxford-AstraZenecaa vs other vaccine brands, Sputnik light vs other vaccine brands, and Pfizer-BioNTech vs other vaccine brands), history of Covid-19 infection (positive history vs no history of Covid-19 infection before vaccination), and co-morbidities (yes vs no). These selected factors entered into the model concurrently. The second multivariable logistic regression model was developed to identify factors associated with severe adverse effects (vs no, mild, and moderate side effects). the selected factors included age (<40 vs ≥40), gender (females vs males), smoking history (smoker vs non-smoker), occupation (healthcare worker vs non healthcare worker), seasonal influenza shot (received it vs did not receive it), vaccine brand (Oxford-AstraZenecaa vs other vaccine brands, Sputnik light vs other vaccine brands, and Pfizer-BioNTech vs other vaccine brands), history of Covid-19 infection (positive history vs no history of Covid-19 infection before vaccination), co-morbidities (yes vs no), diabetes mellitus (vs no diabetes mellitus), and hypertension (vs no hypertension).

Results

Demographic characteristics by vaccination status and severity of side effects

Of 3523 total participants who completed the survey, 14 participants who refused to be included in the study were excluded (completion rate = 99.6%). Of 3509 participants enrolled in the study, 1672 (47.6%) received at least one dose of the Covid-19 vaccine while 1837 (52.3%) remain unvaccinated. Of 1672 participants with at least one dose of Covid-19, 316 (18.9%) were partially vaccinated and 1356 (81.1%) were fully vaccinated. Males represented 1662 (47.4%) and females represented 1847 (52.6%) of the sample. The age group 20 to 29 years represented a majority in the sample 1380 (39.3%). Participants in the age category 30 to 59 years were lower in the vaccinated group 689 (41.2%) compared with the unvaccinated group 819 (44.6%) (p-value < .001). Regarding residency, people who live in rural areas were lower in the vaccinated 341 (20.4%) compared with the unvaccinated group 552 (30.0%) (p-value < .001). In contrast, Syrians who live in cities or who took the vaccine outside Syria were higher in the vaccinated group 1160 (69.4%) and 171 (10.2%) compared with the unvaccinated group 1244 (67.7%) and 41 (2.2%) (p-value < .001) respectively. Further data about participants residing outside Syria are available in the Supplementary Table 1. There were higher proportions of healthcare workers in the vaccinated group 660 (39.5%) compared with the unvaccinated group 380 (20.7%) (p-value < .001). Participants with a history of known allergy, chronic co-morbidity, and smoking were lower in the vaccinated group 208 (12.4%), 369 (22.1%), and 727 (43.5%) compared with the unvaccinated group 288 (15.7%), 459 (25.0), and 902 (49.1%) (p-value = 0.006, 0.042, and < 0.001) respectively. Participants who received an influenza shot last year were higher in the vaccinated group 406 (24.3%) compared with the unvaccinated group 87 (4.7%) (p-value < .001) ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic features by vaccination status and side effect severity.

The 1837 unvaccinated participants reported the following reasons for not taking the vaccine: concern about the vaccines side effects 815 (44.4%), unconvinced of the vaccine benefits 762 (41.5%), will not contract Covid-19 as previously contracted the virus 400 (21.8%), medical exemption 94 (5.1%), and vaccine unavailability 84 (4.6%).

Of the 1672 vaccinated participants, 788 (47.1%) had mild side effects, 374 (22.3%) had moderate side effects, 366 (21.9%) had no side effects, and 144 (8.6%) had severe side effects. Regarding gender, a higher proportion of females suffered from severe side effects 104 (72.2%) compared with males 214 (58.5%) (p-value < .001). Reported severe side effects was higher among participants in the age categories 16–20 years 16 (11.0%), 20–29 years 60 (8.3%), 30–39 years 29 (9.5%), and 40–49 years 34 (15.0%) compared with the age categories 50–59 years 4 (2.6%) and 60≤ years 1 (0.9%) (p-value < .001) ().

Participants with chronic co-morbidities reported higher numbers of mild side effects 156 (42.3%) compared with no side effects 78 (21.1%) (p-value < .001). Of the co-morbidities reported, diabetes mellitus was associated with higher numbers of mild side effects 27 (32.1%) compared with no side effects 21 (25.0%) (p-value < .001), while allergies, respiratory disease, and hematological disease were associated with higher numbers of severe side effects 60 (28.8%), 13 (23.2%), and 4 (36.4%) compared with no side effects 31 (14.9%), 10 (17.9%), and (0.0%) (p-value < .001), (p-value = 0.001), and (p-value = 0.001), respectively ().

The majority 591 (81.3%) of smokers reported post-vaccine side effects compared with no side effects 136 (18.7%) (p-value = 0.048). A history of Covid-19 infection was associated with higher numbers of vaccine side effects 583 (82.6%) compared with no side effects 123 (17.4%) (p-value = 0.001). Participants who received an influenza vaccine (flu jab) reported higher numbers of mild side effects 192 (47.3%) and no side effects 133 (32.8%) compared with moderate side effects 60 (14.8%) and severe side effects 21 (5.2%) (p-value < .001) ().

Covid-19 vaccine side effects and complications by vaccine brand

Vaccine brands available in Syria at the time of the study were AstraZeneca-Oxford 552 (33.0%), Sputnik light 294 (17.5%), Pfizer-BioNTech 280 (16.7%), Sputix v 203 (12.1%), Sinophram 140 (8.4%), Sinovac 93 (5.6%), Johnson & Johnson 58 (3.5%), and Moderna 52 (3.1%). The majority of symptoms started within 12 to 24 h 614 (47.0%) while the minority started after 48 h 36 (2.8%) (p-value = 0.001) ().

Table 2. Covid-19 vaccine side effects by vaccine brand.

The most common reported side effects were tiredness and fatigue 1028 (61.5%), pain at the injection site 933 (55.8%), low-grade fever 684 (40.9%), headache 648 (38.8%), and muscle pain 615 (36. 8%). Tiredness and fatigue were higher among AstraZeneca-Oxford 377 (68.3%) and Sputnick light 200 (68.0%) compared with Sinophram 67 (47.9%) and Sinivac 39(41.9%) (p-value < .001). Headache was more common among Moderna 27 (51.9%) compared with Sinovac 23 (24.7%) (p-value < .001). Low grade fever (<39) was more common among Johnson & Johnson 32 (55.2%) compared with Sinovac 26 (28.0%) (p-value = 0.001). High grade fever was more common among AstraZeneca 90 (16.3%) compared with Pfizer-BioNTech 14 (5.0%) (p-value < .001). Chills were higher among AstraZeneca 157 (28.4%) compared with Sinovac 5 (5.4%) (p-value < .001). Pain at the injection site was more common among Sputnik light 190 (64.6%) compared with Sinovac 31 (33.3%) (p-value < .001). Swelling, redness, and/or temperature at the injection site were more common among Moderna 15 (28.8%) compared with Sinovac 5 (5.4%) (p-value < .001). Joint pain was more common among Johnson & Johnson 25 (43.1%) compared with Pfizer-BioNTech 65 (23.2%) (p-value < .001). Myalgia was more common among AstraZeneca 261 (47.3%) compared with Sinopharm 30 (21.4%) (p-value < .001). Diarrhoea was more common among Johnson & Johnson 7 (12.1%) compared with Sputnick light 2 (0.7%) (p-value = 0.001). Blurred vision was higher among AstraZeneca 22 (4.0%) compared with Johnson & Johnson 0 (0.0%) (p-value = 0.028). Sweating was more common among Johnson & Johnson 19 (32.8%) compared with Sinopharm 18 (12.9%) and Sinovac 12 (12.9%) (p-value < .001). Cough was more common among Moderna 14 (26.9%) compared with Sputnick light 20 (6.8%) (p-value < .001). Nasal congestion was more common among AstraZeneca 97 (17.6%) compared with Sputnick light 21 (7.1%) (p-value < .001). Runny nose was more common among Johnson & Johnson 8 (13.8%) compared with Sputnick light 10 (3.4%). Sore throat was more common among AstraZeneca 76 (13.8%) compared with Sinopharm 9 (6.4%) (p-value = 0.028). Laziness was more common among AstraZeneca 247 (44.7%) compared with Sinovac 18 (19.4%) (p-value < .001). Insomnia was more common among Sputnick light 87 (29.6%) compared with Sinopharm 24 (17.1%) (p-value = 0.006). Dysrhythmia was more common among AstraZeneca 64 (11.6%) compared with Sinopharm 2 (1.4%). Hypotension or hypertension was more common among Moderna 5 (9.6%) compared with Johnson & Johnson 0 (0.0%) (p-value < .001). Chest pain was more common among Johnson & Johnson 5 (8.6%) compared with Moderna 1 (1.4%) (p-value = 0.002). Dyspnoea was more common among AstraZeneca 57 (10.3%) compared with Sinopharm 5 (3.6%) (p-value = 0.012). Anxiety was more common among Johnson & Johnson 8 (13.8%) compared with Sinopharm 0 (0.0%) (p-value < .001) ().

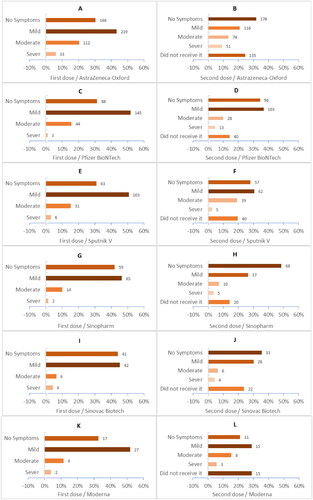

Regarding Covid-19 vaccine symptom severity, the Sinopharm vaccine was associated with a higher percentage of no side effects 51 (36.4%) compared with Johnson & Johnson 7 (12.1%) (p-value < .001), while most of the mild side effects were associated with Sputnik light 168 (57.1%) compared with AstraZeneca 215 (38.9%) (p-value < .001). Moderate side effects were most reported among participants who received Johnson & Johnson 21 (36.2%) compared with Sinovac 8 (8.6%) (p-value < .001). Severe side effects were most associated with AstraZeneca 83 (15.0%) compared with Sinopharm 5 (3.6%) (p-value < .001) (). Post-vaccination side effect severity varied across the first and second doses (). Shockingly, severe side effects were higher after the second dose of most vaccines, including AstraZeneca, Pfizer-BioNTech, Sinopharm, and Moderna (, and ).

The duration of post-vaccination symptoms were reported as follows, >12 h 262 (20.1%), 12-24 h 508 (38.9%), 1-2 days 380 (29.1%), 3 days to 1 week 105 (8.0%), 1-2 weeks 23 (1.8%), and >2 weeks 28 (2.1%) (p-value = 0.011) (). Participants, whose symptoms lasted over 2 weeks, self-reported the following symptoms, pain at the injection site 20 (1.2%), muscle or joint pain 13 (0.8%), fatigue 11 (0.7%), dysrhythmia 5 (0.3%), menstrual abnormalities 4 (0.5%), headache 3 (0.2%), and nasal congestion 2 (0.1%). Other symptoms include low white blood cell count and low platelet count, swollen legs, leg purpura, and hypertension, which were each reported among 1 (0.1%) participant.

The proportion of participants who took painkillers for their symptoms were higher among AstraZeneca 377 (68.3%), Johnson & Johnson 39 (67.2%), Sputnik Light 182 (61.9%), Sputnik v 122 (60.1%), and Moderna 31 (59.6%) compared with Pfizer-BioNTech 139 (49.6%), Sinopharm 69 (49.3%), and Sinovac 42 (45.2%). The highest number of required hospitalization post-vaccination was among AstraZeneca 34 (6.2%) ().

Serious medical complications, such as blood clots and low platelet counts were reported by 5 (0.3%) and 2 (0.1%) respectively. Anaphylaxis shock 1 (0.1%), seizures 1 (0.1%), and cardiac infarction 1 (0.1%) were only reported among those who took the AstraZeneca vaccine ().

Regarding vaccine efficacy, a minority reported having Covid-19 infection after taking the first dose 129 (7.7%) and after taking two doses 117 (7.0%) (p-value < .001). The highest Covid-19 reinfection rate after the first dose was among Sinovac 12 (12.9%), whereas after the second dose was among Sinopharm 21 (15.0%) (p-value < .001) ().

Comparing Covid-19 vaccines by type of formulation (mRNA, inactivated, and viral-vector), showed that viral-vector vaccines were associated with a higher percentage of side effects 905 (81.8%) compared with m-RNA vaccines 250 (75.3%) and inactivated vaccines which were associated with lowest post vaccination side effects 151(64.8%) (p-value < .001). Viral- vector vaccines were also associated with higher percentage of severe side effects and use of painkillers 111 (10.0%) and 720 (65.0%) respectively compared to other types of formation (p-value = < 0.001). The highest reported Covid-19 reinfection rate after the first dose and the second dose were among inactivated vaccines 23 (9.9%) and 26 (11.2%) retrospectively (p- value = 0.013) ().

Multivariate logistic regression analysis

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the variables including age, sex, smoking, occupation, influenza vaccine, vaccine brand, history of Covid-19 infection, and co-morbidities and their association with the development of side effects versus no side effects post-vaccination. The logistic regression model was statistically significant for the following factors, age <40 (vs. ≥40; OR: 1.866, p-value < .001), females (vs. males; OR: 1.696, p-value < .001), current smoker (vs. non-smoker; OR: 1.428, p-value = .006), did not receive Influenza shot last year (vs. did receive Influenza shot last year OR: 1.929, p-value < .001), AstraZeneca vaccine (vs. other vaccine brands OR: 1.426, p-value = .021), history of Covid-19 infection pre-vaccination (vs. no history of Covid-19 infection pre-vaccination OR: 1.317, p-value = .034), and co-morbidities (vs. no co-morbidities, OR: 1.438, p-value .029) were significantly associated with post-vaccination side effects ().

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression analysis on variables associated with side effects and severe side effects after Covid-19 vaccination.

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the variables including age, sex, smoking, occupation, influenza vaccine, vaccine brand, history of Covid-19 infection, co-morbidities, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus and their association with the development of severe side effects versus no, mild, and moderate side effects post-vaccination. The logistic regression model was statistically significant for the following factors, age <40 (vs. ≥40; OR: 2.113, p-value = 0.008), females (vs. males; OR: 2.245, p-value < .001), did not receive influenza shot last year (vs. did receive Influenza shot last year OR: 1.697, p-value = 0.041), AstraZeneca (vs. other vaccine brands; OR: 2.799, p-value < .001), co-morbidities (vs. no co-morbidities; OR: 1.993, p-value = 0.008), and diabetes mellitus (vs. no diabetes mellitus; OR: 2.788, p-value = 0.007) were significantly associated with severe post-vaccination side effects ().

Discussion

Multiple vaccines have been developed during the past two years; these vaccines must be available, safe, and effective [Citation22], with the aim to decrease the death and infection rates. Vaccine hesitancy represents a big obstacle despite all the efforts to counter the stigma [Citation23]. Regarding vaccine status in Syria, vaccine hesitancy is reducing the vaccination prevalence among the population. In our study 47.6% of participants were vaccinated, much higher than the actual vaccination rate reported in the country (9.3%) [Citation6]. The reason for this difference may be due to unreported bias, unvaccinated individuals refuse to express their opinion in a questionnaire distributed by healthcare providers due to medical mistrust of the medical system and Conspiracy theories [Citation24]. A staggering 44.4% of unvaccinated participants reported that they were concerned about the vaccine’s side effects. Several studies in the United Kingdom and the United States of America showed that the main cause of vaccine hesitancy was concern about the side effects of the vaccines [Citation25,Citation26]. Despite, implementing various strategies to scale up vaccination campaigns and conduct vaccination at government institutions, universities, and schools, 4.6% of participants mentioned that they would like to take the vaccine, but the vaccine was not available. Syrians can receive the vaccine whether or not they are pre-registered through an online platform [Citation7]. Our study showed that vaccine hesitancy was higher among rural areas, and this was consistent with previous Syrian studies [Citation27,Citation28]. A possible cause of this is the misunderstanding and myths regarding Covid-19 vaccines and conspiracy beliefs, which is more common in the Syrian countryside. Furthermore, we found that participants with a history of chronic co-morbidities or with known allergies were unwilling to get vaccinated. The fear of the vaccine side effects among those groups can be attributed to misinformation about Covid-19 vaccines in low-income countries [Citation29]. Participants aged 30 to 59 were linked to the unvaccinated group. A study from Jordan indicated that the older age groups (>35 years old) were less likely to take the Covid-19 vaccines compared to younger age groups [Citation30]. On the other hand, our data revealed higher vaccine acceptance among healthcare workers (HCW). In Syria, HCW were the first to receive priority access to vaccines [Citation28]. HCW are also aware of the importance of vaccination to help protect them during occupational exposure and to prevent the spread of the disease among patients and the community [Citation31]. Also, participants who received the influenza shot last year were linked to the vaccinated group and this was coherent with another study conducted in Jordan [Citation30].

Regarding vaccinated participants, 78.1% were symptomatic after receiving a Covid-19 vaccine. The most common symptoms according to our results were tiredness and fatigue, pain at the injection site, low-grade fever, headache, and muscle pain. This was consistent with previous studies conducted in Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and the Czech Republic [Citation32–34]. The symptoms were most frequently reported within 12 to 24 h after vaccination and lasted mainly one day. This result was in line with a study conducted in the Czech Republic and the United Kingdom [Citation34,Citation35]. The overwhelming majority of symptoms were mild and moderate in severity 64.6% and 28.6%, respectively. And this was consistent with what was announced by CDC and WHO [Citation11,Citation12]. Whereas, 8.6% of participants reported severe symptoms post-vaccination. A study from Jordan reported similar results [Citation36]. However, an observational study in the United Arab Emirates and a cross-sectional study of healthcare workers in the United States of America showed various proportions of severe symptoms [Citation13,Citation37]. The majority of vaccinated participants used painkillers to alleviate post-vaccination discomfort; the highest proportion of those was among AstraZeneca-Oxford (ChAdOx1) vaccine recipients. Similar findings were observed in a study conducted in Togo [Citation38]. In comparison between the first dose and second dose, we observed that the side effects tend to be more severe after receiving the second dose, specifically AstraZeneca-Oxford (ChAdOx1) and Pfizer BioNTech (BNT162b2). This was similar to previous studies which demonstrated that systematic and local side-effects were more common after receiving the second dose of Covid-19 vaccines [Citation35,Citation39], and coherent with what was announced by CDC [Citation14]. Serious side effects after Covid-19 vaccination are rare but can occur [Citation11], in our study 3.9% of vaccinated participants reported they required medical consultation or hospital visit. This was similar to a study conducted in the United Arab Emirates [Citation13]. Serious side effects included blood clots, thrombocytopenia, anaphylaxis shock, seizures, and cardiac infarction. Despite the rarity of these serious side effects [Citation40], and the lack of consensus on their association with vaccines [Citation41], all of them have been previously mentioned in the medical literature [Citation42–46].

In this study, people with a history of previous Covid-19 infection had greater odds of post-vaccine side effects. This finding was similar to previous studies conducted in the United Kingdom and Italy [Citation44,Citation47]. Participant characteristics of young age (<40 years), female sex, current smokers, history of chronic co-morbidities, AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccine, and did not receive influenza shot last year had greater odds of post-vaccination side effects. These results were consistent with data from a large cohort study in the United States of America [Citation39]. Furthermore, this study revealed that participants with younger age (<40 years), female sex, history of chronic co-morbidities, AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccine, did not receive influenza shot last year also, and diabetes mellitus had greater odds of severe post-vaccination side effects. This finding was in line with previous studies conducted in Togo and Mexico [Citation38,Citation48]. Also, in this study participants with diabetes mellitus were more vulnerable to severe post-vaccination side effects. Another study found that patients at greatest risk of developing side effects post-vaccination include those with a history of type-2 diabetes [Citation49].

Pain at the injection site was the most frequent symptom, and the reason behind this might be due to delayed-onset injection site reactions [Citation40,Citation50], or what is called ‘Covid arm’, which is a delayed but harmless allergic reaction [Citation51,Citation52]. Irregular heartbeats were reported by participants, although it is a rare prolonged side effect, a research study published in Nature Medicine looks at the possible link between different cardiac arrhythmias and Covid-19 vaccination [Citation53]. Menstrual abnormalities were self-reported as a prolonged symptom, and many studies have shown a possible link between the Covid-19 vaccine and menstrual abnormalities [Citation54,Citation55].

Syrian vaccination rates are extremely low by global standards [Citation6], but the explosion of Covid-19 infections has not been a problem which may be because the true scope of the Covid-19 outbreak in Syria is unknown due to limited testing capacity, underreporting, and lack of access to healthcare. However, a previous study showed that the increases in Covid-19 are unrelated to levels of vaccination across 68 countries and 2947 counties in the United States [Citation56]. the highest infection rate after the first dose of Covid-19 vaccines was observed among the Sinovac (Coronavac) vaccine, which indicated that this vaccine provided poor immune protection against Covid-19. A previous study in Malaysia found that Coronavac effectiveness against Covid-19 infection waned after 3–5 months of full vaccination [Citation57]. Sinopharm (BIBP) Vaccines had the highest infection rate after the second dose compared to all the other vaccine brands. A study from the Kingdom of Bahrain showed that compared to individuals vaccinated with AstraZeneca, Pfizer-BioNTech, or Sputnik V, those vaccinated with the Sinopharm vaccine had a higher risk of post-vaccination infection [Citation58].

The cross -vaccine comparison of our study showed that viral vector-based vaccines were associated with the more frequent side effects. Our results are consistent with the findings of a German cross-sectional study [Citation59]. A study from Algeria revealed that side effects are more prevalent among viral vector vaccines than inactivated virus vaccines [Citation60], and this was adherent with our findings. In contrast, we found that inactivated virus vaccines were associated with lower adverse effects following vaccination. A systematic review study on the safety profile of covid-19 vaccines was showed that the low rates of local and systemic reactions were significantly lower among inactivated vaccines [Citation61]. Inactivated virus vaccine showed higher reinfection rates after vaccination and this finding were consistent with other previous studies [Citation62,Citation63].

Study limitations

The data deduced may not be generalized to the wider Syrian population. Credible published national data on the socio-demographic distribution of the population are unavailable to assess the representativeness of the study’s sample. The authors used a convenience sampling strategy involving various social media platforms and convenient location interviews. Syrians of an older age group represented a minority due to limited internet access. The elderly, the most vulnerable population, require vaccine protection; therefore, a study must be conducted to assess the vaccine uptake among this age group. As such, reaching out to these vulnerable populations must be prioritized. Additionally, as this study is a self-reported survey, the responses may be subject to recall bias.

Conclusion

Most of the reported vaccine side effects were mild in severity and well-tolerated. However, age < 40 years, females, not receiving influenza shot, AstraZeneca vaccine, co-morbidities, and diabetes mellitus were factors significantly associated with severe post-vaccination side effects. Viral vector-based vaccines were associated with the more frequent side effects. Inactivated virus vaccines were associated with lower adverse effects and higher reinfection rates following vaccination. Larger prospective studies to understand the causes of rare serious adverse events are needed to overcome vaccine hesitancy among people. The long-term adverse effects of vaccines will become more important in the future. However, these adverse effects may not be known unless the medical environment is favourable and access to medical care is easy.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Syrian Private University (SPU). The IRB at SPU did not provide us with a number. This research has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s). Participation in the study was voluntary and participants were assured that anyone who was not inclined to participate or decided to withdraw after giving informed consent would not be victimized. All information collected from this study was kept strictly confidential. All study methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Authors’ contributions

MN and SA conceptualised the study, participated in the design, participated in data collection, wrote the study protocol, performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the results, did a literature search, and drafted the manuscript. MF participated in data collection, participated in data encoding, and designed the figures. DCG were involved in the collection of data. FM revised the final draft of the paper. All authors read and approved the final draft.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (12.4 KB)Acknowledgments

We are thankful to all who participated in the study. We would like to specifically thank the data collection group. We would also like to thank Batoul Bakkar, and Wassim Gharz Edine for their contibution by publishing the survey on social media applications.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in [repository name ‘zenodo’] at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7425817 .

Additional information

Funding

References

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5.

- Han E, Tan MMJ, Turk E, et al. Lessons learnt from easing COVID-19 restrictions: an analysis of countries and regions in Asia Pacific and Europe. Lancet. 2020;396(10261):1525–1534. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32007-9.

- Farrar c. A race for the covid-19 vaccine: a story of innovation and collaboration 2020 Available from: https://www.carnallfarrar.com/a-race-for-the-covid-19-vaccine-a-story-of-innovation-and-collaboration/. accessed 24 November 2020.

- BIO SJASoC-VwWEPEP. Status of COVID-19 Vaccines within WHO EUL/PQ evaluation process WHO2021 [updated 07 July 2022. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/pqweb/sites/default/files/documents/Status_COVID_VAX_07July2022.pdf.

- pandem-ic. Mapping our unvaccinated world: pandem-ic; 2022 Available from: https://pandem-ic.com/mapping-our-unvaccinated-world/. accessed September 12, 2022 2022.

- Roser HRaEMaLR-GaCAaCGaEO-OaJHaBMaDBaM. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). 2020. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations?country=SYR.

- WHO. WHO and Syria combine efforts to raise COVID-19 vaccine accessibility and uptake. 2022. http://www.emro.who.int/syria/news/who-and-syria-combine-efforts-to-raise-covid-19-vaccine-accessibility-and-uptake.html. (accessed 9 Feb 2022).

- WHO. Update on COVID-19 vaccination in Syria, 14 June 2021. 2021. http://www.emro.who.int/syria/news/update-on-covid-19-vaccination-in-syria.html. (accessed 14 June 2021).

- Prevention CfDCa. Vaccines for COVID-19 Centers for disease control and prevention2022 [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/index.html. accessed September 16, 2022 2022.

- WHO. COVID-19 advice for the public: getting vaccinated: WHO; 2022updated 13 April 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines/advice.

- Prevention CfDCa. Possible side effects after getting a COVID-19 vaccine 2022 [updated Aug. 15, 2022. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/expect/after.html#:∼:text=Fever%2C%20headache%2C%20fatigue%2C%20and,are%20. accessed 2022.

- WHO. Side effects of COVID-19 vaccines: WHO; 2021 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/side-effects-of-covid-19-vaccines#:∼:text=Common%20side%20effects%20of%20COVID%2D19%20vaccines&text=Reported%20side%20effects%20of%20COVID,muscle%20pain%2C%20chills%20and%20diarrhoea. accessed 31 March 2021.

- Ganesan S, Al Ketbi LMB, Al Kaabi N, et al. Vaccine side effects following COVID-19 vaccination among the residents of the UAE-An observational study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:876336. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.876336.

- worldometers. Coronavirus cases [Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. accessed September 15, 2022 2020.

- Szilagyi PG, Thomas K, Shah MD, et al. The role of trust in the likelihood of receiving a COVID-19 vaccine: results from a national survey. Prev Med. 2021;153:106727. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106727.

- UK M. Public Lost Confidence in Governments’ Handling of COVID Over Time: Survey: Medscape UK; 2022 [updated September 15, 2022. Available from: https://www.medscape.co.uk/viewarticle/public-lost-confidence-governments-handline-covid-over-time-2022a1001s3v. accessed July 12, 2022.

- Tran BX, Boggiano VL, Nguyen LH, et al. Media representation of vaccine side effects and its impact on utilization of vaccination services in Vietnam. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:1717–1728. doi: 10.2147/ppa.S171362.

- Cascini F, Pantovic A, Al-Ajlouni YA, et al. Social media and attitudes towards a COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic review of the literature. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;48:101454. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101454.

- Prevention CfDCa. Possible Side Effects After Getting a COVID-19 Vaccine: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2022 [updated Sept. 14, 2022. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/expect/after.html. accessed September 16, 2022.

- Nomura S, Yoneoka D, Shi S, et al. An assessment of self-reported COVID-19 related symptoms of 227,898 users of a social networking service in Japan: has the regional risk changed after the declaration of the state of emergency? Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2020;1:100011. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100011.

- Adorni F, Prinelli F, Bianchi F, et al. Self-reported symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a nonhospitalized population in Italy: cross-sectional study of the EPICOVID19 web-based survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(3):e21866. doi: 10.2196/21866.

- Pormohammad A, Zarei M, Ghorbani S, et al. Efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Vaccines. 2021;9(5):467. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050467.

- Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2021;9(2):160. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020160.

- Simione L, Vagni M, Gnagnarella C, et al. Mistrust and beliefs in conspiracy theories differently mediate the effects of psychological factors on propensity for COVID-19 vaccine. Front Psychol. 2021;12:683684. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.683684.

- Robertson E, Reeve KS, Niedzwiedz CL, et al. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK household longitudinal study. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;94:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.03.008.

- Lucia VC, Kelekar A, Afonso NM. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students. J Public Health. 2021;43(3):445–449. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa230.

- Swed S, Baroudi I, Ezzdean W, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among people in syria: an incipient crisis. Ann Med Surg. 2022;75:103324. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103324.

- Mohamad O, Zamlout A, AlKhoury N, et al. Factors associated with the intention of syrian adult population to accept COVID19 vaccination: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1310. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11361-z.

- Bekele F, Fekadu G, Wolde TF, et al. Patients’ acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine: implications for patients with chronic disease in low-resource settings. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021;15:2519–2521. doi: 10.2147/ppa.S341158.

- El-Elimat T, AbuAlSamen MM, Almomani BA, et al. Acceptance and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines: a cross-sectional study from Jordan. PLOS One. 2021;16(4):e0250555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250555.

- Shekhar R, Sheikh AB, Upadhyay S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in the United States. Vaccines. 2021;9(2):119. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020119.

- Alhazmi A, Alamer E, Daws D, et al. Evaluation of side effects associated with COVID-19 vaccines in Saudi Arabia. Vaccines. 2021;9(6):674. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060674.

- Almufty HB, Mohammed SA, Abdullah AM, et al. Potential adverse effects of COVID19 vaccines among iraqi population; a comparison between the three available vaccines in Iraq; a retrospective cross-sectional study. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;15(5):102207. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.102207.

- Riad A, Pokorná A, Attia S, et al. Prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine side effects among healthcare workers in the Czech Republic. J Clin Med. 2021;10(7):1428. doi: 10.3390/jcm10071428.

- Menni C, Klaser K, May A, et al. Vaccine side-effects and SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination in users of the COVID symptom study app in the UK: a prospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(7):939–949. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(21)00224.

- Hatmal MM, Al-Hatamleh MAI, Olaimat AN, et al. Side effects and perceptions following COVID-19 vaccination in Jordan: a randomized, cross-sectional study implementing machine learning for predicting severity of side effects. Vaccines. 2021;9(6):556. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060556.

- Cohen DA, Greenberg P, Formanowski B, et al. Are COVID-19 mRNA vaccine side effects severe enough to cause missed work? Cross-sectional study of health care-associated workers. Medicine. 2022;101(7):e28839. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000028839.

- Konu YR, Gbeasor-Komlanvi FA, Yerima M, et al. Prevalence of severe adverse events among health professionals after receiving the first dose of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 coronavirus vaccine (Covishield) in Togo, March 2021. Arch Public Health. 2021;79(1):207. doi: 10.1186/s13690-021-00741-x.

- Beatty AL, Peyser ND, Butcher XE, et al. Analysis of COVID-19 vaccine type and adverse effects following vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):e2140364. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40364.

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389.

- Mahase E. Covid-19: AstraZeneca vaccine is not linked to increased risk of blood clots, finds European medicine agency. BMJ. 2023;380:741. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n774.

- Wise J. Covid-19: European countries suspend use of Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine after reports of blood clots. BMJ. 2021;372:n699. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n699.

- Kuter DJ. Exacerbation of immune thrombocytopenia following COVID-19 vaccination. Br J Haematol. 2021;195(3):365–370. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17645.

- Mathioudakis AG, Ghrew M, Ustianowski A, et al. Self-reported real-world safety and reactogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines: a vaccine recipient survey. Life. 2021;11(3):249. doi: 10.3390/life11030249.

- Assiri SA, Althaqafi RMM, Alswat K, et al. Post COVID-19 Vaccination-Associated neurological complications. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2022;18:137–154. doi: 10.2147/ndt.S343438.

- Maadarani O, Bitar Z, Elzoueiry M, et al. Myocardial infarction post COVID-19 vaccine - coincidence, kounis syndrome or other explanation - time will tell. JRSM Open. 2021;12(8):20542704211025259. doi: 10.1177/20542704211025259.

- Ossato A, Tessari R, Trabucchi C, et al. Comparison of medium-term adverse reactions induced by the first and second dose of mRNA BNT162b2 (comirnaty, Pfizer-BioNTech) vaccine: a post-marketing italian study conducted between 1 january and 28 february 2021. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2023;30(4):e15. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2021-002933.

- Camacho Moll ME, Salinas Martínez AM, Tovar Cisneros B, et al. Extension and severity of self-reported side effects of seven COVID-19 vaccines in mexican population. Front Public Health. 2022;10:834744. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.834744.

- Ahamad MM, Aktar S, Uddin MJ, et al. Adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccination: machine learning and statistical approach to identify and classify incidences of morbidity and post-vaccination reactogenicity. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;11(1):31. DOI:10.3390/healthcare11010031

- Kelso JM. Anaphylactic reactions to novel mRNA SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine. 2021;39(6):865–867. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.084.

- Ramos CL, Kelso JM. COVID arm’: very delayed large injection site reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(6):2480–2481. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.03.055.

- Wei N, Fishman M, Wattenberg D, et al. COVID arm’: a reaction to the moderna vaccine. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:92–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.02.014.

- Patone M, Mei XW, Handunnetthi L, et al. Risks of myocarditis, pericarditis, and cardiac arrhythmias associated with COVID-19 vaccination or SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2022;28(2):410–422. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01630-0.

- Muhaidat N, Alshrouf MA, Azzam MI, et al. Menstrual symptoms after COVID-19 vaccine: a cross-sectional investigation in the MENA region. Int J Womens Health. 2022;14:395–404. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.S352167.

- Laganà AS, Veronesi G, Ghezzi F, et al. Evaluation of menstrual irregularities after COVID-19 vaccination: results of the MECOVAC survey. Open Med. 2022;17(1):475–484. doi: 10.1515/med-2022-0452.

- Subramanian SV, Kumar A. Increases in COVID-19 are unrelated to levels of vaccination across 68 countries and 2947 counties in the United States. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021;36(12):1237–1240. doi: 10.1007/s10654-021-00808-7.

- Suah JL, Husin M, Tok PSK, et al. Waning COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness for BNT162b2 and CoronaVac in Malaysia: an observational study. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;119:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.03.028.

- AlQahtani M, Du X, Bhattacharyya S, et al. Post-vaccination outcomes in association with four COVID-19 vaccines in the om of Bahrain. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):9236. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-12543-4.

- Klugar M, Riad A, Mekhemar M, et al. Side effects of mRNA-Based and viral Vector-Based COVID-19 vaccines among german healthcare workers. Biology. 2021;10(8):752. doi: 10.3390/biology10080752.

- Lounis M, Rais MA, Bencherit D, et al. Side effects of COVID-19 inactivated virus vs. Adenoviral vector vaccines: experience of Algerian healthcare workers. Front Public Health. 2022;10:896343. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.896343.

- Wu Q, Dudley MZ, Chen X, et al. Evaluation of the safety profile of COVID-19 vaccines: a rapid review. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):173. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-02059-5.

- Dadras O, Mehraeen E, Karimi A, et al. Safety and adverse events related to inactivated COVID-19 vaccines and novavax;a systematic review. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2022;10(1):e54. doi: 10.22037/aaem.v10i1.1585.

- Zheng C, Shao W, Chen X, et al. Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: a literature review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;114:252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.11.009.