Abstract

Background

The aim of this current study was to identify the prevalence and risk factors of H. pylori infection in the low-risk area of gastric cancer in China, and evaluate the value of different gastric cancer screening methods.

Methods

An epidemiological study was conducted in Yudu County, Jiangxi, China, and participants were followed up for 6 years. All participants completed a questionnaire, laboratory tests and endoscopy. Patients were divided into H. pylori positive and negative groups, and risk factors for H. pylori infection were identified using multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Results

A total of 1962 residents were included, the prevalence of H. pylori infection was 33.8%. Multivariate analysis showed that annual income ≤20,000 yuan (OR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.18–1.77, p < 0.001), loss of appetite (OR: 1.71, 95% CI: 1.29-2.26, p < 0.001), PG II >37.23 ng/mL (OR: 2.11, 95% CI: 1.50–2.97, p < 0.001), G-17 > 1.5 and ≤5.7 pmol/L (OR: 2.52, 95% CI: 1.93–3.30, p < 0.001), and G-17 > 5.7 pmol/L (OR: 1.96, 95% CI: 1.48–2.60, p < 0.001) were risk factors of H. pylori infection, while alcohol consumption (OR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.54–0.91, p = 0.006) was a protective factor. According to the new gastric cancer screening method, the prevalence of low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia in the low-risk group, medium-risk group and high-risk group was 4.4%, 7.7% and 12.5% respectively (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

In a low-risk area of gastric cancer in China, the infection rate of H. pylori is relatively low. Low income, loss of appetite, high PG II, and high G-17 were risk factors for H. pylori infection, while alcohol consumption was a protective factor. Moreover, the new gastric cancer screening method better predicted low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia than the ABC method and the new ABC method.

1. Introduction

H. pylori is a kind of microaerophilic, spiral gram-negative bacterium, which infects more than half of the world’s population [Citation1]. Chronic H. pylori infection is closely related to the occurrence of gastric cancer and is recognized as a Type I carcinogen [Citation2]. Long-term population-based cohort studies have shown that eradication of H. pylori can significantly reduce gastric cancer morbidity and mortality [Citation3,Citation4]. Whereas, the majority of patients with H. pylori infection do not present obvious clinical symptoms in the early stages [Citation5]. Therefore, the identification of risk factors for H. pylori infection can help in early diagnosis and timely treatment. Many studies have suggested that H. pylori infection is associated with socioeconomic status, environmental conditions, and lifestyle habits [Citation6–8]. A prospective study conducted in an area with a high prevalence of gastric cancer found that annual family income and education level were independent predictors for H. pylori infection [Citation9]. However, no studies have investigated the infection rate and risk factors of H. pylori in low-risk areas of gastric cancer in China.

Gastric cancer is the second most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in China [Citation10]. Most patients are found to have advanced gastric cancer, while the 5-year survival rate of early gastric cancer after radical resection is over 90% [Citation11]. Therefore, many scholars have constructed early screening models for gastric cancer based on serological examination, including the ABC method and the new ABC method [Citation12,Citation13]. A new screening method proposed by Li et al. [Citation14] has shown a good ability to identify high-risk populations in areas with a high prevalence of gastric cancer in China. However, the effectiveness of these screening methods has not been validated in a low-risk region of gastric cancer in China. The age-standardized incidence rate of gastric cancer in Yudu County of China is 9.35 per 100,000, which is similar to the incidence rate of gastric cancer in Europe and high-income North America [Citation15]. Hence, we conducted an epidemiological survey to determine the prevalence and risk factors of H. pylori infection in the low-risk area of gastric cancer in China and evaluate the value of different gastric cancer screening methods.

2. Methods

2.1. Population and data collection

An epidemiological study was performed in Yudu County, Jiangxi Province, China. From August 1, 2015 to January 30, 2016, the cluster-sampling method was adopted to conduct a field survey in 3 rural villages in the east, west and south of Yudu country, and the follow-up was conducted until August 30, 2022. People aged between 40 and 69 years were included in the study, and the exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the coexistence of significant concomitant illnesses including heart diseases, renal failure, hepatic disease, previous abdominal surgery or H. pylori eradication; (2) patients with a history of gastric cancer or other malignant tumours; (3) subjects who cannot tolerate gastroscopy; (4) not willing to participate in the study; and (5) incomplete demographic data. The collected data included gender, age, body mass index (BMI), education level, marital status, size of family, family history of gastric cancer, socioeconomic conditions, smoking, drinking, eating habits, gastrointestinal symptoms, laboratory tests and etc. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, and all patients provided written informed consent.

All the staff who participated in the field investigation received unified training and collected information through standardized questionnaires [Citation16]. We set up temporary stations in three villages to publicize the project. Through the village committee, we convened the people eligible for gastric cancer screening, and explain the importance, the benefits and potential risks of participating in screening to eligible subjects. In addition, we also informed villagers through the telephone that they could participate in the public welfare gastric cancer screening program. All participants signed informed consent and completed questionnaires, laboratory examinations (serum anti-H. pylori IgG antibody, PG I, PG II and G-17) and endoscopy. A smoker was defined as a patient who smoked more than one cigarette per day for more than one year. Alcohol consumers are defined as those who consume more than 100 ml of alcohol per week for at least a year. Frequent consumption of fresh vegetables, fresh fruits, preserved foods, fried foods and hot foods was defined as more than three times per week. Endoscopic resection was performed when high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia or early gastric cancer was found. When advanced gastric cancer is detected by endoscopy, surgical treatment is scheduled. For subjects with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, gastroscopy was performed annually to detect the lesions in time, and the remaining participants received endoscopic examination again five years later. A new gastric screening method was divided into three groups according to age, gender, serum anti-H. pylori IgG antibody, PG I/II ratio, G-17, pickled food and fried food. The low-risk group, medium-risk group and high-risk group were defined as scores ≤11, 12-16, and 17-25, respectively [Citation14]. ABC method was divided into four groups (Group A: H. pylori (-) and PG (-); Group B: H. pylori (+) and PG (-); Group C: H. pylori (+) and PG (+); Group D: H. pylori (-) and PG (+)) according to the levels of serum anti-H. pylori IgG antibody, PG I and PG II, and PG I ≤ 70 ug/L and PG I/II ≤3 were classified as PG positive [Citation12]. The new ABC method was divided into three groups (Group A: G-17 (-) and PG (-); Group B: G-17 (+) and PG (-), or G-17 (-) and PG (+); Group C: G-17 (+) and PG (+)) according to the levels of serum PG I, PG II and G-17, and PG I ≤ 70 ug/L and PG I/II ≤7 were classified as PG positive, G-17 ≤ 1 pmol/L or G-17 ≥ 15 pmol/L were classified as G-17 positive [Citation13].

2.2. Laboratory examination and endoscopy

Blood samples of 5 ml were collected from each subject by peripheral venipuncture under sterile conditions. Blood samples were centrifuged and serum concentrations of PG I, PG II and G-17 and anti-H. pylori IgG antibodies were detected using commercial ELISA kits (Biohit Oyj, Helsinki, Finland). According to previous studies [Citation17–19], the cut-off values of PGs were defined as PG I ≤ 70 ng/mL, PG II >37.23 ng/mL, PG I/II ≤3, and G-17 critical values ≤1.5, >1.5 and ≤5.7, >5.70 pmol/L. All subjects underwent white light gastroscopy (GIF-Q260J; Olympus Optical Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), and tissue biopsy was performed on the suspected lesion site during the gastroscopy. The diagnosis of intraepithelial neoplasia is based on biopsy pathology, low-grade intra-epithelial neoplasia includes mild to moderate dysplasia, and high-grade intra-epithelial neoplasia refers to severe dysplasia.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR) depending on whether they followed a normal distribution, and were statistically analyzed by Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test. Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test was performed to analyze the categorical data. Patients were divided into H. pylori positive and negative groups according to the status of serum anti-H. pylori IgG antibody. Potential risk factors for H. pylori infection were screened through univariate analysis, and variables with p < 0.05 in univariate analysis were included in multiple logistic regression analysis. The covariables adjusted in the multivariate logistic regression analysis model include education level, annual income, drinking, hiccups, belching, loss of appetite, PG I, PG II, PG I/II ratio and G-17. Risk factors were estimated by calculating the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). A P-values < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The chi-square test was used to compare different screening methods for low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. SPSS software version 26.0 (IBM; Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics of H. pylori positive and negative groups

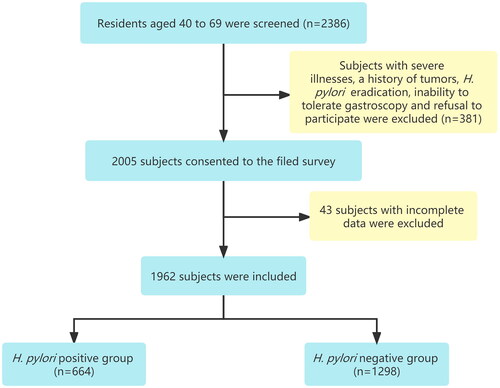

From August 2015 to January 2016, 2386 people aged between 40 and 69 years were screened, a total of 2005 subjects consented to the field survey, and 1962 subjects were eventually included in this study (). The overall prevalence of H. pylori was 33.8% (664/1962). As shown in , the median (range) age of the H. pylori-positive group was 53 (47–60) years, and that of the H. pylori-negative group was 52 (46–60) years. In terms of education level, people with only primary school in the H. pylori-positive group were significantly higher than those in the H. pylori-negative group (p = 0.023). The median family size was 5 (4–7) in the H. pylori-positive group and 5 (4–6) in the H. pylori-negative group, and there was no significant difference between the two groups. However, 62.5% (415/664) of subjects in the H. pylori-positive group had an annual income of less than 20,000 yuan, significantly more than 53.9% (700/1298) in the H. pylori-negative group. In the H. pylori-negative group, 21.1% were alcohol consumers, compared with 16.4% in the H. pylori-positive group, showing a statistically significant difference (p = 0.013). The frequency of consumption of pickled food, fried food and hot food in H. pylori-positive group was significantly higher than that in H. pylori-negative group. There was no significant difference between the two groups in gender, BMI, marriage status, family population, family history of gastric cancer, smoking, fresh vegetables and fruit consumption.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of H. pylori positive and negative groups.

3.2. Comparison of gastrointestinal symptoms between H. pylori positive and negative groups

A total of 829 people (42.3%) had gastrointestinal symptoms including bloating, heartburn, regurgitation, nausea, hiccups, belching, loss of appetite and stomachache (Supplementary Table 1). The symptoms of hiccups, belching and loss of appetite were more common in H. pylori-positive group than in H. pylori-negative group.

3.3. Comparison of endoscopic findings and laboratory examinations between H. pylori positive and negative groups

Endoscopic examination found peptic ulcers in 22% of the H. pylori-positive group, compared with 12.2% of the H. pylori-negative group, with a statistical difference between the two groups. In terms of laboratory examinations, PG I, PG II and G-17 levels in serum were significantly higher in the H. pylori-positive group than in H. pylori-negative group ().

Table 2. Comparison of endoscopic findings and laboratory examinations between H. pylori positive and negative groups.

3.4. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for H. pylori infection

Univariate analysis revealed that annual income ≤20,000 yuan, hiccups, belching, loss of appetite, PG II >37.23 ng/mL, PG I/II ratio ≤3, G-17 > 1.5 and ≤5.7 pmol/L, and G-17 > 5.7 pmol/L were positively correlated with H. pylori infection, whereas drinking, PG I ≤ 70ug/L and high school education were negatively associated with H. pylori infection.

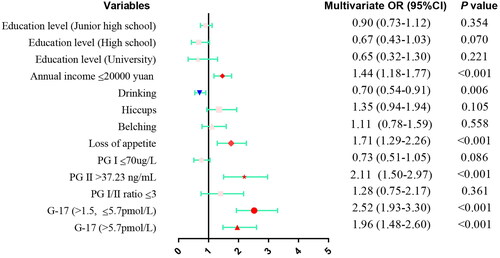

Risk factors for H. pylori infection with p < 0.05 in the univariable analysis were subsequently examined by multivariate analysis ( and ). The results showed that annual income ≤20,000 yuan (OR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.18–1.77, p < 0.001), loss of appetite (OR: 1.71, 95% CI: 1.29–2.26, p < 0.001), PG II >37.23 ng/mL (OR: 2.11, 95% CI: 1.50–2.97, p < 0.001), G-17 > 1.5 and ≤5.7 pmol/L (OR: 2.52, 95% CI: 1.93-3.30, p < 0.001), and G-17 > 5.7 pmol/L (OR: 1.96, 95% CI: 1.48–2.60, p < 0.001) were risk factors of H. pylori infection, while alcohol consumption (OR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.54–0.91, p = 0.006) was a protective factor.

Figure 2. The results of multivariate analysis of risk factors for H. pylori infection were presented as Forest plot. OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; PG: pepsinogen.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for H. pylori infection.

3.5. Comparison of different screening methods for low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia

In our initial field investigation, 120 patients with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, 1 patient with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, and 1 patient with gastric cancer. According to the new gastric cancer screening method, the prevalence of low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia in the low-risk group, medium-risk group and high-risk group was 4.4%, 7.7% and 12.5% respectively (p < 0.001). The prediction effect was significantly better than ABC method and the new ABC method (). We followed the population enrolled in this study for up to 6 years, and one patient developed from low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia to gastric cancer during the follow-up period.

Table 4. Comparison of different screening methods for low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia.

4. Discussion

H. pylori is considered to be one of the causative factors of many gastroduodenal diseases [Citation20–22]. The prevalence of H. pylori infection varies around the world [Citation23], and this study focuses on the prevalence of H. pylori infection and risk factors in areas with low incidence of gastric cancer in China. In the present research, we found that the prevalence of H. pylori infection was 33.8%, which was lower than that in developing countries and similar to that in developed countries [Citation24]. Data from the Jiangxi Provincial Center for Disease Control showed that the incidence of gastric cancer in Yudu County in 2016 was only 9.35 per 100,000, which was much lower than the national average level [Citation15]. It may be due to the lower infection rate of H. pylori in the area.

We further investigated the predictors of H. pylori infection in low-prevalence areas of gastric cancer. Research shows that PG II >37.23 ng/mL, G-17 > 1.5 and ≤5.7 pmol/L, and G-17 > 5.7 pmol/L were independent risk factors for H. pylori infection. Many studies have also found that H. pylori-positive patients have significantly higher PG II levels than H. pylori-negative patients, so it can be used as a marker of active H. pylori infection [Citation25–27]. Zhou JP also found that the level of G-17 in patients with H. pylori infection was significantly higher [Citation19]. This is consistent with our findings. In addition, loss of appetite is also strongly associated with H. pylori infection. This suggests that H. pylori testing should be considered in patients with this gastrointestinal symptom. In our study, annual income ≤20,000 yuan is also a predictor of H. pylori infection. A large number of studies have proved that lower socioeconomic status is a predictive factor for H. pylori infection, because it may lead to poor living environment and sanitary conditions [Citation9,Citation28]. Whereas, we found that alcohol consumption was negatively associated with H. pylori infection. A study from Japan showed that drinking was negatively and dose-dependently associated with H. pylori infection [Citation29]. A national cross-sectional study in Turkey also revealed a lower risk of H. pylori infection in regular alcohol consumers [Citation30]. Previous studies have shown that wine has a significant bactericidal effect on Escherichia coli in vitro [Citation31], and we suspect that alcohol may also have a certain degree of bactericidal effect on H. pylori. Another study has shown that moderate alcohol consumption may prevent H. pylori infection by facilitating the eradication of the bacteria [Citation32]. Apart from that, some alcoholic beverages can stimulate gastric acid secretion, which may eliminate H. pylori by reducing the PH in the stomach [Citation33].

Low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia is considered a precancerous lesion, and a large sample cohort study reported that the incidence rate of gastric cancer in patients with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia was 25.6 times higher than that in the general population [Citation34]. Therefore, early screening for low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia is crucial. In this study, since only one gastric cancer patient was screened in the field investigation, we validated three screening methods for patients with low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia. The results revealed that the new screening method had better differentiation performance, with the prevalence of low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia in the low-risk group, medium-risk group and high-risk group was 4.4%, 7.7% and 12.5% respectively. We followed up on the included subjects for up to 6 years. One patient was detected with early gastric cancer in the second year of follow-up and underwent endoscopic resection in time. Hence, the application of the new screening method in low-incidence areas of gastric cancer may be helpful for the early identification of high-risk groups of gastric cancer. In addition, close follow-up of high-risk groups of gastric cancer will help to improve the diagnosis rate of early gastric cancer and take corresponding measures to improve the prognosis of patients.

There were several limitations of the present study. On the one hand, the sample size was relatively small, and large sample size studies can further confirm these conclusions. On the other hand, due to human and material resources and other factors, the field investigation was only carried out in three rural villages in Yudu County, and these results may not completely reflect the real situation in the region.

In conclusion, in a low-risk area of gastric cancer in China, the infection rate of H. pylori is relatively low. Low income, loss of appetite, high PG II, and high G-17 were risk factors for H. pylori infection, while alcohol consumption was a protective factor. Moreover, the new gastric cancer screening method better predicted low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia than the ABC method and the new ABC method.

Authors’ contributions

Foqiang Liao collected data, analyzed relevant information, and drafted the manuscript; Zhenhua Zhu collected data and drafted the manuscript; Shusheng Zhu, Jianhua Wan and Chenglai Fan conducted data collection and analysis. Nonghua Lu, Xu Shu and Xu Zhang designed the study and supervised the structure and quality of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

The Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University approved this study.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (12.8 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The clinical data were not made public to protect the privacy of the patients. However, the data can be made available upon reasonable request by email.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, et al. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(2):1–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.022.

- Plummer M, Franceschi S, Vignat J, et al. Global burden of gastric cancer attributable to Helicobacter pylori. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(2):487–490. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28999.

- Chiang TH, Chang WJ, Chen SL, et al. Mass eradication of Helicobacter pylori to reduce gastric cancer incidence and mortality: a long-term cohort study on Matsu Islands. Gut. 2021;70:243–250.

- Ford AC, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy to prevent gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2020;69(12):2113–2121. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320839.

- Owyang SY, Luther J, Kao JY. Helicobacter pylori: beneficial for most? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;5(6):649–651. doi: 10.1586/egh.11.69.

- Laszewicz W, Iwańczak F, Iwańczak B. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Polish children and adults depending on socioeconomic status and living conditions. Adv Med Sci. 2014;59(1):147–150. doi: 10.1016/j.advms.2014.01.003.

- Dore MP, Malaty HM, Graham DY, et al. Risk factors associated with Helicobacter pylori infection among children in a defined geographic area. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(3):240–245. doi: 10.1086/341415.

- Bastos J, Peleteiro B, Pinto H, et al. Prevalence, incidence and risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in a cohort of Portuguese adolescents (EpiTeen). Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45(4):290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.11.009.

- Shi R, Xu S, Zhang H, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese populations. Helicobacter. 2008;13(2):157–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2008.00586.x.

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660.

- Suzuki H, Oda I, Abe S, et al. High rate of 5-year survival among patients with early gastric cancer undergoing curative endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19(1):198–205. doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0469-0.

- Miki K. Gastric cancer screening by combined assay for serum anti-Helicobacter pylori IgG antibody and serum pepsinogen levels – ABC method. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2011;87(7):405–414. doi: 10.2183/pjab.87.405.

- Ni DQ, Lyu B, Bao HB[, et al. Comparison of different serological methods in screening early gastric cancer. ]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2019;58:294–300.

- Cai Q, Zhu C, Yuan Y, et al. Development and validation of a prediction rule for estimating gastric cancer risk in the Chinese high-risk population: a nationwide multicentre study. Gut. 2019;68(9):1576–1587. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317556.

- He Y, Wang Y, Luan F, et al. Chinese and global burdens of gastric cancer from 1990 to 2019. Cancer Med. 2021;10(10):3461–3473. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3892.

- Wang KJ, Wang RT. Meta-analysis on the epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2003;24:443–446.

- Miki K, Urita Y. Using serum pepsinogens wisely in clinical practice. J Dig Dis. 2007;8(1):8–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-9573.2007.00278.x.

- Bang CS, Lee JJ, Baik GH. Prediction of chronic atrophic gastritis and gastric neoplasms by serum pepsinogen assay: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. J Clin Med. 2019;8(5):657. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050657.

- Zhou JP, Liu CH, Liu BW, et al. Association of serum pepsinogens and gastrin-17 with Helicobacter pylori infection assessed by urea breath test. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:980399. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.980399.

- Ford AC, Mahadeva S, Carbone MF, et al. Functional dyspepsia. Lancet. 2020;396(10263):1689–1702. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30469-4.

- Lee YC, Dore MP, Graham DY. Diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Annu Rev Med. 2022;73:183–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042220-020814.

- Yan L, Chen Y, Chen F, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on gastric cancer prevention: updated report from a randomized controlled trial with 26.5 years of follow-up. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(1):154–162.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.039.

- Leja M, Grinberga-Derica I, Bilgilier C, et al. Review: epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2019;24 (1):e12635. doi: 10.1111/hel.12635.

- Zamani M, Ebrahimtabar F, Zamani V, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the worldwide prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(7):868–876. doi: 10.1111/apt.14561.

- Di Mario F, Crafa P, Barchi A, et al. Pepsinogen II in gastritis and Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2022;27(2):e12872. doi: 10.1111/hel.12872.

- Okuda M, Lin Y, Mabe K, et al. Serum pepsinogen values in Japanese junior high school students with reference to Helicobacter pylori infection. J Epidemiol. 2020;30(1):30–36. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20180119.

- Haj-Sheykholeslami A, Rakhshani N, Amirzargar A, et al. Serum pepsinogen I, pepsinogen II, and gastrin 17 in relatives of gastric cancer patients: comparative study with type and severity of gastritis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(2):174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.016.

- Kotilea K, Bontems P, Epidemiology TE. Diagnosis and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1149:17–33.

- Ogihara A, Kikuchi S, Hasegawa A, et al. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and smoking and drinking habits. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15(3):271–276. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02077.x.

- Ozaydin N, Turkyilmaz SA, Cali S. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori in Turkey: a nationally-representative, cross-sectional, screening with the 13C-Urea breath test. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1215. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1215.

- Weisse ME, Eberly B, Person DA. Wine as a digestive aid: comparative antimicrobial effects of bismuth salicylate and red and white wine. BMJ. 1995;311(7021):1657–1660. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7021.1657.

- Murray LJ, Lane AJ, Harvey IM, et al. Inverse relationship between alcohol consumption and active Helicobacter pylori infection: the Bristol Helicobacter project. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(11):2750–2755. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07064.x.

- Liszt KI, Walker J, Somoza V. Identification of organic acids in wine that stimulate mechanisms of gastric acid secretion. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60(28):7022–7030. doi: 10.1021/jf301941u.

- Li D, Bautista MC, Jiang SF, et al. Risks and predictors of gastric adenocarcinoma in patients with gastric intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(8):1104–1113. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.188.