Abstract

Background

Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) is a serious public health issue. Dietary changes form the core of MetS treatment. The adherence to dietary recommendations is critical for reducing the severity of MetS components and preventing complications. However, the adherence to dietary recommendations was not adequate among adults with MetS. This study utilizes the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) to develop an individualized WeChat mini program-based behavioural change intervention aimed at strengthening adherence to dietary recommendations in people with MetS.

Methods

The BCW theory was used to design an individualized WeChat mini program-based behavioural change intervention. A descriptive qualitative study was conducted to identify the determinants of adherence to dietary recommendations in individuals with MetS. The study was conducted at the health promotion centre of a prominent general university hospital in Zhejiang, China. Subsequently, the intervention functions (IFs) and policy categories were selected following the identified determinants. Afterwards, behaviour change techniques (BCTs) were chosen to translate into potential intervention strategies, and the delivery mode was determined.

Results

Our study identified fifteen barriers to improve the adherence to dietary recommendations in this population. These were linked with six IFs: education, training, persuasion, enablement, modelling, and environmental restructuring. Then, twelve BCTs were linked with the IFs and fifteen barriers. The delivery mode was a WeChat mini program. After these actions, an individualized WeChat mini program-based behavioural change intervention was developed to enhance adherence to dietary recommendations for individuals with MetS.

Conclusions

The BCW theory helped scientifically and systematically develop an individualized WeChat mini program-based behavioural change intervention for individuals with MetS. In the future, our research team will refine and upgrade the WeChat mini program and then test the usability and effectiveness of the individualized WeChat mini program-based behavioural change intervention program.

Key Messages

This is the first paper to specify the content and active ingredients of an individualized WeChat mini program-based behavioural change intervention using a systematic evidence- and theory-based method for individuals with MetS.

The findings can be used to provide guidance to improve dietary adherence, and ultimately improve the lives of people with MetS.

This methodology can serve as a reference for other researchers who are developing behavioural change interventions.

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a serious public health problem. It was characterised by increased waist circumference (WC), high systolic blood pressure (SBP) or diastolic blood pressure (DBP), high triglyceride (TG) levels, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and elevated fasting blood glucose (FBG) [Citation1]. Approximately 25% of adults worldwide are estimated to have MetS [Citation2,Citation3]. The general prevalence of MetS is 31.1% among adults ≥20 years old in China [Citation4]. Globally, MetS increases the risk of cardiovascular mortality by 2.5 times, the risk of diabetes by 5 times, the risk of coronary heart and cerebrovascular disease by 2 times, and the risk of all-cause mortality by 1.5 times [Citation5]. Otherwise, MetS costs are trillions and will continue to increase [Citation6]. Therefore, it is critical to develop effective prevention and treatment programs to control MetS.

MetS is a constellation of established risk factors of cardiovascular diseases. The World Health Organization states that almost 80% of cardiovascular diseases can be averted through a healthy diet, increased physical activity levels, and smoking cessation [Citation7]. Therefore, diet plays a pivotal role in the prevention and treatment of MetS, and people with MetS should follow dietary recommendations [Citation8,Citation9]. Although dietary recommendations seem simple, their implementation and maintenance remain unsatisfactory. Chen et al. [Citation10] reported that 61% of the participants (n = 241) exhibited suboptimal dietary adherence. Zheng et al. [Citation11] showed that the diet score was not high among patients with MetS. Suboptimal adherence increases the likelihood of MetS components and the risk of complications [Citation12,Citation13]. A greater understanding of how to improve adherence is needed to enable individuals with MetS to benefit from dietary recommendations. Thus, intervention strategies to overcome inadequate adherence are a research priority.

Numerous interventions aimed at improving adherence to a healthy diet have been identified as having varying degrees of effectiveness. However, most diet interventions were delivered by face to face, booklet, or telephone among adults with MetS [Citation11,Citation14], and necessitated significant dedication from both patients and health care professionals due to the financial implications, time requirements, and absence of immediate outcomes. This greatly limited the implementational scalability of interventions for promoting healthy diets. To overcome the existing drawbacks, mobile health (mHealth)-based interventions have been developed as potential solutions. mHealth involves utilizing mobile devices such as phones, tablets, personal digital assistants, and wireless infrastructure to support medical and public health practices [Citation15]. Two systematic reviews found that mHealth-based interventions had the ability to significantly improve diet behaviours [Citation16,Citation17]. Such findings suggest that the use of advanced technologies could provide a valuable means of improving diet adherence.

However, previous mHealth-based diet interventions offered general ‘one-size-fits-all’ dietary recommendations among people with MetS [Citation18,Citation19], which have achieved limited outcomes [Citation20]. Individualized lifestyle education helped patients with MetS adopt lifestyle interventions as part of their daily routine [Citation21]. The concept of individualization refers to designing intervention content based on an individual’s specific characteristics, including existing behaviours, stages of behaviour change, preferences, and barriers [Citation22]. Some studies that provide individualized recommendations may face limitations in offering fully individualized advice due to the limited functionality of mHealth tools such as email, websites, mobile phones, and mobile texts [Citation18,Citation19]. In this case, a WeChat mini program with diversified functions provides solutions for meeting the diversified individual needs of patients with MetS. Nonetheless, no study has been found that develops an individualized WeChat mini program-based intervention to improve dietary compliance among adults with MetS in China.

Moreover, most diet interventions lack systematic theoretical guidance [Citation23,Citation24], which may lead to suboptimal dietary adherence and limit the overall success of interventions [Citation10]. Using theory to change behaviour enhances the chances of intervention success [Citation25,Citation26]. In this context, it is recommended to utilize a theoretical framework when designing an intervention with the goal of enhancing dietary compliance among people with MetS. Behavioural change has multiple theories and models, but the majority of them ignore the background in which the target behaviour occurs, pay little attention to the reflective process, have a static structure, and fail to clarify how to change behaviour [Citation27]. Michie et al. [Citation28] indicated that existing frameworks of behavioural change interventions also lack comprehensiveness, coherence, and behavioural change models. To address the limitations of the above theories and frameworks, the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) framework was created, containing 19 behavioural change frameworks [Citation27]. At present, the BCW has been widely used to design interventions in some contexts. However, we found that the design and development of interventions using the BCW to facilitate adherence to dietary recommendations in people with MetS are scarce.

We aimed to use the BCW to systematically develop an individualized WeChat mini program-based behaviour change intervention to promote adherence to dietary recommendations in adults with MetS in China.

Methods

This study is a component of a comprehensive intervention aimed at promoting a healthy diet and physical activity in individuals with MetS in Mainland China. Our study was performed according to the stages and steps of the BCW guide (see ) [Citation29]. In short, it consisted of three layers (see ), with the COM-B (capability, opportunity, motivation, and behaviour) model serving as its core, which synthesises existing behavioural change theories and explores the determinants of the desired behaviour. Moreover, the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) was incorporated into the BCW to expand upon the COM-B model and more deeply understand the determinants of target behaviour [Citation30]. The second and outer layers of the BCW are the intervention functions (IFs) and policy categories, respectively, which are designed to promote behavioural change [Citation28]. Moreover, the Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy v1 (BCTTv1), which is an active ingredient, has been linked to the BCW to help select specific behaviour change techniques (BCTs) and deliver the IFs [Citation31].

Figure 1. Stages involved in an intervention development using the BCW [Citation27] (used with permission from authors).

![Figure 1. Stages involved in an intervention development using the BCW [Citation27] (used with permission from authors).](/cms/asset/12413c0e-0380-4633-bd87-b9cc553e5e02/iann_a_2267587_f0001_c.jpg)

Figure 2. the Behavior Change Wheel (used with permission from authors) [Citation27].

![Figure 2. the Behavior Change Wheel (used with permission from authors) [Citation27].](/cms/asset/b246da23-c72c-4496-8dd1-89607af20356/iann_a_2267587_f0002_c.jpg)

Stage 1: understand the behaviour

The first stage involved four steps to understand the behaviour.

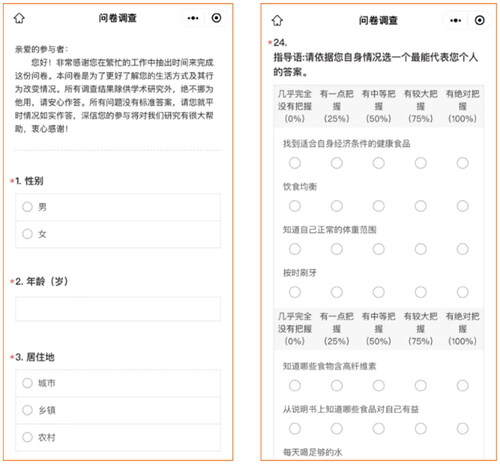

Step 1: define the problem in behavioural terms

Step 1 involved defining the problem in behavioural terms. Doing so required identifying the problem and specifying the behaviour and target population [Citation29]. To define the problem, we reviewed evidence on dietary adherence among people with MetS. The databases PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Library, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, Weipu, and Wanfang were systematically searched using the following keywords: ‘metabolic syndrome’, ‘diet’, ‘nutrition’ and ‘lifestyle’. When applicable, manual searches were performed on the cited references in relevant papers. Furthermore, we conducted a cross-sectional study to investigate the diet behaviours of participants with MetS at the health promotion centre of a prominent general university hospital in Zhejiang, China. From January to May 2021, 288 individuals (≥18 years old) diagnosed with MetS were asked to independently complete the diet survey. One dimension of the Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile II, namely, nutrition, with six items, was used to assess diet behaviours [Citation32]. Each item included four options and was measured on a four-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 4 (routinely). The total score varies between 6 and 24. Two trained researchers contacted the participants and collected self-reported demographic characteristics and diet behaviours from them.

Step 2: select target behaviour

Step 2 aimed to determine which behaviour could address the defined problem. Step 2 involved consideration of all the specific behaviours to potentially target in the intervention design. The BCW suggested starting with 1 or 2 target behaviours and building on these behaviours incrementally [Citation29]. Therefore, not all possible behaviours needed to be included in the intervention. We selected potential target behaviours by reviewing existing literature on diet management measures for individuals with MetS. Furthermore, according to the BCW framework, four criteria were used to select the final target behaviour: (i) how much of an impact changing the behaviour would have on the desired outcome, (ii) how likely it is that the behaviour can be changed, (iii) how likely it is that the behaviour would have a positive or negative impact on other related behaviours, and (iv) how easy it would be to measure the behaviour [Citation29].

Step 3: specify target behaviour

Step 3 involved specifying the context of which the target behaviour occurred, to which there were several components: who would carry out the target behaviour, what they would need to do to achieve change, where and when the behaviour was performed, and how often and with whom. A literature search on diet interventions among people with MetS was undertaken to specify the target behaviour.

Step 4: what needs to change?

Step 4 involved conducting research to explore the barriers and facilitators to the target behaviour. Based on the COM-B model and TDF, a descriptive qualitative method using semi-structured interviews was employed to unravel adherence from the perspective of individuals with MetS. A qualitative descriptive method could provide practitioners with the most direct and essential answers to the questions that concern them; therefore, this method was chosen in our study [Citation33]. This section was performed according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) [Citation34]. The COM-B model includes three domains: capability, opportunity and motivation, which interact with one another to enable behaviour to occur [Citation29]. The TDF includes fourteen domains that can be condensed to fit the three constructions of the COM-B model, as follows: capability (knowledge, cognitive and interpersonal skills, memory, attention and decision processes, behavioural regulation, and physical skills); opportunity (social influences, environmental context, and resources); and motivation (reinforcement, optimism, emotions, social/professional role and identity, beliefs about capabilities, beliefs about consequences, goals, and intentions) [Citation30].

Participants and setting

The present study employed a purposive sampling approach to recruit participants [Citation35].

From May to August 2021, two researchers (CDD and SJ) recruited participants by distributing a recruitment advertisement. Those who agreed to participate in the study were assessed by the researchers to determine the representativeness of their characteristics. Potential participants were provided with information about the study and asked to complete a written informed consent form. The sample size depended on data saturation. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) individuals with MetS who met the diagnostic criteria of the 2009 Joint Scientific Statement [Citation1], (2) individuals without food allergies or intolerances, and (3) individuals who were ≥18 years old. Exclusion criteria were the following: (1) people following specific diets; or (2) people who were unable to communicate effectively.

Data collection

According to the existing literature, the three constructs of the COM-B system, and the fourteen domains of the TDF, our research team developed a semi-structured interview guide (). Through conducting pre-interviews with three patients, the interview guide was further modified and improved. The interview did not strictly follow the present interview guide but was guided by the thoughts and perspectives of the participants. The first author (CDD) conducted and recorded these interviews using a digital recording tool with the permission of the participants. The digital recording was transcribed verbatim within 24 h after the end of the first interview. The study would continue until no new themes emerged, indicating thematic saturation, at which point data collection would stop [Citation36].

Table 1. Interview schedule.

Data analysis

The interview transcript was analysed using Braun and Clarke’s six-step framework [Citation37]: (1) becoming familiar with the data; (2) generating initial codes; (3) searching for themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) writing up the final report. First, CDD listened to and transcribed the audio recordings; checked the transcriptions; and read, listened to again, and reread the final transcripts to become familiar with the data. Simultaneously, CDD took notes for forming hidden codes. Second, the initial codes were developed. Next, the codes were checked and grouped to formulate themes by two researchers (CDD and ZH). These themes were then mapped into the three COM-B model constructs and fourteen TDF domains by two researchers (CDD and SJ). Disagreements and ambiguities were resolved by discussion with a third researcher (YZH).

Rigour

In the process of the data analysis, our research team adhered to the criteria for authenticity, credibility, criticality, and integrity [Citation38]. Authenticity was ensured by two researchers (CDD and YZH) who checked the accuracy of the interview transcriptions. To maintain credibility, our research team discussed any differences related to methodological issues and data analysis. Criticality and integrity were attained through rigorous evaluation of each research decision and conscientious reflection on the researcher’s biases and their potential impact on the research. In addition, the members of our research team are PhD candidates or holders in nursing and have participated several times in qualitative research workshops. These experiences have equipped them with the essential skills of organizing, coding, and analysing textual data. Their experience was instrumental in ensuring the rigor of this research.

Stage 2: identifying intervention options

Steps 5 and 6: identifying IFs and policy categories

According to Michie et al. [Citation29], the relevant IFs and policy categories should be identified based on the results of the COM-B model and TDF diagnosis. The IFs included education, training, restriction, persuasion, incentivization, coercion, modelling, environmental restructuring, and enablement [Citation29]. All the IFs were then evaluated according to the APEASE (affordability, practicability, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, acceptability, side effects/safety, and equity) criteria [Citation29]. Affordability refers to whether the cost of the proposed intervention fits within the budget. Practicality assesses whether the intervention is delivered as intended to the target population. Effectiveness measures the impact of the intervention in achieving desired objectives in a real-world context. Cost-effectiveness evaluates the ratio of effect to cost. Acceptability gauges the appropriateness of the intervention according to relevant stakeholders (public, professional, and political). Side effects/safety considerations involve assessing potential unwanted effects or unintended consequences of the intervention. Equity examines how the intervention may impact disparities in standard of living, wellbeing, or health among different sectors of society [Citation29]. After the IFs were identified, policy categories—including communication/marketing, guidelines, fiscal measures, regulation, legislation, environmental/social planning, and service provision—would normally be determined to assist in the delivery of the identified IFs in accordance with the BCW framework. However, our study was not related to changing policies on diets; therefore, policy categories were not addressed.

Stage 3: identify content and intervention options

Step 7: identify BCTs

Once the relevant IFs were determined, the intervention designers, who were PhD candidates or holders in nursing and who focused on behavioural change in patients with chronic disease, used the BCTTv1 to identify and link the most frequently used BCTs to each IF [Citation29,Citation31]. Furthermore, to identify any additional BCTs, a matrix was applied to link the fifty-nine BCTs from the BCTTv1 to the twelve TDF domains [Citation39]. Additionally, the APEASE criteria were used to assess and narrow the potentially appropriate BCTs by two researchers [Citation29]. If two researchers gave the same reasons for the inclusion and exclusion of BCTs according to the APEASE criteria, which meant that they had the same choice of BCTs, the BCTs would be finalised. Any disagreements were resolved through constructive discussions within our research team. After the BCTs were identified, our research team translated the BCTs into potential intervention content.

Step 8: identify the model of delivery

The delivery model referred to the method(s) of intervention administration, such as self-help, individual, group, telephone, or other modalities [Citation40]. Before deciding the most appropriate delivery mode, the full range of possible delivery models must be considered, including face-to-face, TV, internet, app, and mobile phone text [Citation29]. The delivery model was determined after considering the target behaviour, target population, and specific setting. Specifically, the delivery model was selected based on previous experience with diet intervention development. Additionally, the APEASE criteria were considered to assess the delivery model [Citation29]. Disagreements were discussed within our research team.

Expert consultation

Following the completion of all stages, we synthesised the key findings from each stage. The intervention materials, including the content and format, were sent via email to a panel of twelve experts with diverse academic backgrounds. This panel consisted of advanced nursing practitioners, behavioural science experts, management scientists, and general physicians. Each expert reviewed the materials individually and shared their feedback and comments. After a period of two weeks, all the feedback and comments were collected. Our research team rigorously scrutinised and deliberated on each feedback point and subsequently refined the intervention content and format based on expert input. The review process aimed to ensure the intervention’s relevance, validity, efficacy, and acceptability across multiple disciplines, perspectives, and contexts.

Translating findings into WeChat mini program features

Our research team and software engineers cooperated to convert the intervention content into WeChat mini program features. This collaboration involves the integration of the research team’s expertise in intervention design and evaluation with the software engineers’ skills in programming, user interface design, and quality assurance. The resulting program should not only deliver the intervention content but also provide interactive features that promote user engagement, monitoring, and feedback. Moreover, the program’s design should also consider factors such as accessibility, usability, security, and scalability to ensure its effectiveness, efficiency, and robustness. The research team participates in the entire process of program development, maintains real-time communication with software engineers, and ensures that the program’s features meet the diet needs of patients with MetS.

Ethical consideration

Our study complied with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (grant no. 20210220-32). All participants provided voluntary and informed consent by signing consent forms before commencing the research. The participants were informed that their data was confidential. The first author (CDD) stored the obtained electronic and paper data in a password-protected computer file and a locked drawer, respectively.

Results

Step 1: define the problem in behavioural terms

The systematic review found that a healthy diet formed the core of MetS treatment [Citation41]. Therefore, a healthy diet should not be ignored in MetS management. Through a literature search, evidence was found that low adherence to dietary recommendations was a serious problem among people with MetS [Citation42,Citation43]. Additionally, our research team conducted an empirical survey to understand diet behaviour in a general university hospital in Hangzhou, Zhejiang. The empirical study included 241 individuals with MetS. The results showed that the median diet score was 18.0 (interquartile range [IQR] 17.0–20.0), and 61% of the 241 individuals scored no more than 3.0 points in diet, indicating that individuals did not score high [Citation10]. Hence, we identified the behavioural problem as insufficient adherence to dietary recommendations.

Step 2: select target behaviour

Much evidence is available about how to improve dietary compliance among individuals with MetS. The American Heart Association conference recommended a range of target behaviours, such as a low-fat, high-fibre diet to reduce energy intake by 2142–4184 kJ/d (500–1000 kcal/d); a low intake of saturated and trans-fat and cholesterol; an increased intake of fruit, vegetables, and whole grains; and reduced consumption of simple sugars [Citation44,Citation45]. Bach-Faig et al. [Citation46] suggested a low-to-moderate intake of dairy products, fish, and poultry; a high intake of olive oil and plant foods; a low consumption of red meat and sweets; and a moderate consumption of alcohol. Studies included in the systematic review evaluating the relationship between diet patterns and metabolic syndrome in adult subjects proposed an increased intake of fruit, poultry, fish, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and low-fat dairy products to maintain healthy diet patterns [Citation47]. In addition, an international panel pointed out that an increased intake of unsaturated fat—primarily from olive oil (range of 20-40 g/d), a variety of legumes, cereals (whole grains), fruits, vegetables, fish, nuts, and dairy products—would be beneficial for preventing and managing MetS [Citation9]. Considering the following four criteria: (i) how much of an impact changing the behaviour would have on the desired outcome, (ii) how likely it is that the behaviour can be changed, (iii) how likely it is that the behaviour would have a positive or negative impact on other related behaviours, and (iv) how easy it would be to measure the behaviour [Citation29], we defined the target behaviours as individuals with MetS eating healthily as specified in public health guidelines.

Step 3: specify target behaviour

The target behaviour needed to be specified by detailing who should perform the behaviour, when, where, how, and with whom, which are presented in .

Table 2. Specifying the target behavior.

Step 4: what needs to change?

Participating in the study were twenty-two adults with MetS. The demographic and clinical characteristics can be found in a supplementary file (see Supplementary File 1). The behavioural analysis revealed the barriers and facilitators of target behaviours categorised into the COM–B model and TDF domains. In our study, 39 themes were identified based on the interview findings, including fifteen barriers, twenty-three facilitators, and one that could be classified as both (see ). Of the 39 extracted themes, 38.5% fell into the reflective motivation category (n = 15), 30.8% fell into the psychological capability category (n = 12), 12.8% fell into the physical opportunity category (n = 5), 7.7% fell into the automatic motivation category (n = 3), 7.7% fell into the social opportunity category (n = 3) and 2.6% fell into the physical capability category (n = 1). Furthermore, the most commonly coded TDF domains were memory, attention, and decision processes (n = 7; 17.9%); environmental context and resources (n = 5; 12.8%); beliefs about consequences (n = 5; 12.8%); and beliefs about capabilities (n = 4; 10.3%). The remaining findings (46.2%) were coded into ten other TDF domains. The barriers that have been identified require modification and adjustment: perceived poor knowledge about a healthy diet, not monitoring food, eating out frequently and eating more, not being accustomed to eating breakfast, eating fast, preferring sweets, preferring red meat, not being accustomed to eating whole grains, having a negative peer influence, having family meals that are dense in oil and fat, lacking time, experiencing hot weather, having work meals that are dense in oil, and lacking self-control. The majority of the barriers were linked to psychological capability and reflective motivation. displays the results of the behavioural analysis.

Table 3. Behavioural analysis of the dietary recommendation adherence. The subthemes were used to develop the intervention.

Steps 5 and 6: identifying IFs and policy categories

According to the BCW, we linked the behavioural assessment with the IFs (see ). Specifically, six IFs were selected for this intervention design: education, training, persuasion, enablement, environmental restructuring, and modelling. Restriction was not acceptable for individuals with MetS or health care professionals, as rules often require legislative changes to be enforceable and acted upon.

Table 4. Linking the results of the behavioral assessment with the IFs.

Step 7: identify BCTs

As shown in , we identified twelve BCTs that could be used in the intervention. The selected BCTs could serve more than one IF. The identified BCTs included information about health consequences (5.1), prompts/cues (7.1), self-monitoring of behaviour (2.3), demonstration of the behaviour (6.1), instruction on how to perform the behaviour (4.1), social support (practical) (3.2), restructuring the social environment (12.2), focusing on past success (15.3), verbal persuasion about capability (15.1), feedback on behaviour (2.2), goal setting (behaviour) (1.1), and reviewing behaviour goal(s) (1.5).

Table 5. Identification of the possible BCTs that could be used in the intervention.

Step 8: identify model of delivery

A systematic review reported that the mHealth-based intervention effectively improved individuals’ eating behaviours [Citation17]. A WeChat mini program is an important component of mHealth. It does not require download or uninstallation, is convenient and inexpensive, and allows users to receive health services without temporal or spatial limitations [Citation48]. The features of the WeChat mini program met the APEASE criteria. As a result, our research selected a WeChat mini program as the delivery method.

Expert consultation

A summary of the final included COM-B, TDF, barriers, IFs, BCTs, and intervention content is presented in . As shown in step four, most barriers were related to the COM-B model of capability and opportunity, and the TDF domains of knowledge, memory, attention, and decision processes, and environmental context and resources. Specifically, to increase knowledge about MetS, it may be useful to provide adults with MetS with health education about the diagnosis, health consequences, or diet knowledge of MetS via the WeChat mini program. In terms of unhealthy diet habits, instruction on how to perform a behavior, demonstration of the behavior, and social support were also identified as valuable BCTs. Provision of instruction on how to perform a healthy diet, observable samples of individuals who maintain healthy diets, and suggestions on how to eat healthily could improve individuals’ diet habits. Emphasis on restructuring the social environment and providing social support in this intervention, such as advising family members to maintain a healthy diet and advising individuals to seek help from others via the WeChat mini program, may create a good diet atmosphere for individuals with MetS. Furthermore, the other intervention components included providing via the WeChat mini program: (i) suggestions or feedback about the target behaviour; (ii) reminders for adults with MetS to record the food varieties and/or amount they ate; (iii) the ability for individuals with MetS to set their diet goals or plans per day as specified in public health guidelines and review the goals or plans; and (iv) positive messages telling the person that they can maintain a healthy diet. The experts’ feedback on the intervention content and format encompassed the following aspects:

Table 6. Combined link between COM-B model, TDF domains, IFs, BCTs and intervention content.

‘Advise individuals to minimize the time spent with friends who eat more to reduce food intake via the program.’ should be revised as ‘It is recommended that patients minimize their social activities at night as much as possible, or schedule them at noon if necessary.’

‘Provide information on the definition, drawbacks, and diet knowledge related to metabolic syndrome via the program.’ should be revised as ‘Provide information about the definition, etiology, drawbacks, and individualized diet knowledge of metabolic syndrome via the program.’

‘Share your own diet status with others via the program’ should be added.

‘Provide a healthy diet and cooking assistance.’ should be added.

‘The implementation process of urging a scientific and reasonable diet.’ should be added.

Translating findings into WeChat mini program features

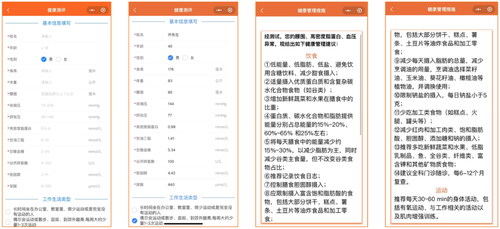

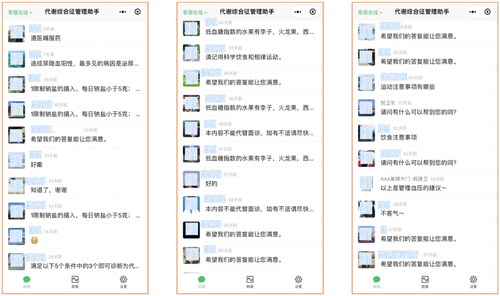

As shown in , the program developed by the research team in collaboration with software engineers consists of three main modules: ‘Health Assessment’, ‘My Records’, and ‘My Homepage’, which could be subdivided into ten functional modules.

The ‘Health Assessment’ module: users need to fill in their personal information, including name, age, gender, height, weight, WC, SBP, DBP, HDL-C, TG, FBG, and other indicators. Based on the collected data, the program provides individualized diet recommendations ().

The ‘My Records’ module includes three parts. Firstly, the ‘Daily Records’ section allows users to record their diet type and amount as a check-in each day. The program can intelligently generate individualized daily reports in chart form, including types and amounts of food intake, for patients to review the gap between their own diet and diet goals recommended by related guidelines (). The second part is ‘Behaviour Review and Advice’, where users need to compare their diet type and amount against the program’s recommendations and select reasons not to follow diet recommendations. The program can then provide individualized solutions (). In the third part, the ‘Recent Seven-Day Report’ section, users can view individualized charts generated by the system, which includes food types and amounts in the last 7 days, for patients to review the gap between their own diet and diet recommendations ().

The ‘My Homepage’ module includes six parts. The ‘Knowledge Encyclopedia’ section provides text and video information about MetS diagnosis, etiology, clinical manifestations, complications, exercise guidance, diet guidance, etc. Users can click on the corresponding content to read and save it (). The ‘Health Consultation, Reminders, Help, and Feedback’ module provides individualized feedback according to patients’ questions and provides diet reminders. In addition, if users have suggestions or need help regarding the contents and use of the MetS health management mini program, they can leave a message for feedback. The team members will later reply (). In the ‘Questionnaire Survey’ section: users can complete online assessments, including self-assessment questionnaires on health-promoting lifestyles, MetS prevention and treatment knowledge, health behaviour self-efficacy, quality of life, etc. The program calculates the questionnaire score and generates a report that is sent to the user’s phone or email (). The ‘Operation Guide’ introduces the usage rules of this program. The ‘Disclaimer’ explains the conditions under which this program is not liable. The ‘Privacy Statement’ introduces the privacy protection of user information.

In addition, within each module, patients can share their own diet management status with family and friends in order to increase compliance with healthy eating through external incentives or support.

Discussion

The BCW theory helps scientifically and systematically develop an individualized WeChat mini program-based dietary adherence intervention. To our knowledge, this is the first paper to specify the content and active ingredients of an individualized WeChat mini program-based behavioural change intervention using a systematic evidence- and theory-based method for individuals with MetS. According to the BCW, our study identified four components to the COM-B model, six TDF domains, six IFs, and twelve BCTs based on patients’ barriers to a dietary recommendation that could be used to formulate an individualized WeChat mini program-based behavioural change intervention program that aims to strengthen adherence to dietary recommendations among individuals with MetS in China. The findings can be used to provide guidance to improve dietary adherence, and ultimately improve the lives of people with MetS. Additionally, this methodology can serve as a reference for other researchers who are developing behavioural change interventions.

Developing an effective adherence intervention requires an in-depth identification of the key elements affecting the target behaviour. In our study, some barriers were identified based on the COM-B model and the TDF. In terms of psychological capability, the participants reported having poor MetS knowledge about their diagnosis and lacking knowledge about a healthy diet for managing MetS, which was in accordance with Wang et al.’s findings [Citation49]. Moreover, we also found a phenomenon in which many participants ate out frequently and ate more. Most of the participants expressed that the aim of eating out was to establish a working relationship with customers. Additionally, other unhealthy diet habits were identified, such as eating sweets, eating red meat, eating fast, or not being accustomed to eating whole grains or breakfast. Previous research reported similar findings [Citation50] as it aimed to explore the barriers and facilitators to adherence to the diet guidelines among children and unrelated adults and noted that the primary barriers encompassed a lack of cooking skills, poor eating habits, inadequate knowledge of recommendation/portion/health benefits, etc. In our study, nearly none of the patients recorded the varieties of food they consumed. As reported, the self-monitoring of unwanted behaviour could lead to a decrease in such behaviour [Citation51]. Therefore, intervention strategies should encourage self-monitoring of unhealthy foods.

With respect to social opportunity, negative peer influence was a major barrier to a healthy diet. In contrast, positive peer support enhanced adherence to a healthy diet [Citation52]. Additionally, physical opportunities, including family and work dietary atmospheres, needed improvement. Families were a support source through the role model of healthy eating [Citation53]. In our study, some family meals were oil- and fat- dense. For these families, the diet patterns must be adjusted and a balanced diet must be maintained to create a good dietary environment. Moreover, to maintain a healthy diet at work, people did not eat out or in a canteen but ate a lunch they brought to work [Citation54], which provided a reference for a future diet intervention design. In addition, our study reported that the lack of time and hot weather influenced participant adherence to dietary recommendations. Regarding reflective motivation, several of the participants expressed difficulties in adhering to a healthy diet. They stated that the main reason was a lack of self-control when maintaining a healthy diet. This finding fit well with the existing literature [Citation55,Citation56], which indicated that low adherence to dietary recommendations was associated with less self-control.

The most common IFs were education, persuasion, modelling, enablement, and environmental restructuring in a mHealth-based medication adherence intervention [Citation57] and a healthy eating intervention [Citation58,Citation59], which was consistent with our study. Furthermore, our study identified twelve potential BCTs (of 93) aligned to six IFs to address the identified barriers. Similar to the findings of our study, Rohde et al. [Citation59] identified fourteen BCTs (e.g. rewards, graded tasks, or self-monitoring) in the mHealth-based design aimed at improving eating habits. To increase vegetable consumption, Mummah et al. [Citation60] included eighteen BCTs (e.g. social comparison, feedback, goal setting, and prompts/cues) to develop a theory-based mHealth application. Thus, BCT combinations were often used in interventions to improve diets. In future research, researchers should focus on which BCTs or combinations of BCTs are the most effective. The present study was not related to changing policy on diets. However, the evidence gathered from the intervention development process may offer valuable reference information pertaining to policy categories aimed at promoting behaviour changes.

Our study determined the intervention content based on the identified BCTs. To enhance its scientific and practical feasibility, expert consultations were conducted. Through expert consultation, the intervention content was enriched and the intervention model of delivery-a WeChat mini program was affirmed. The mini program is an important component of mHealth and is grounded in WeChat, which is a widely popular social networking app used in China, and it’s also considered to be one of the leading social networks worldwide. The program supports developers to implement individualized functions, and can provide customized contents and experiences according to the needs of patients. Participants may also access a WeChat mini program-based intervention without needing to log onto a particular website or download a new app [Citation48]. Other advantages include cost-effectiveness, automation, and the convenience of accessing healthcare services anytime and anywhere [Citation48].

We invited software engineers to design the WeChat mini program with more individualized elements based on the identified intervention content. The developed program can provide individualized dietary recommendations, behaviour modification solutions, and goal achievement feedback based on data uploaded by patients. Furthermore, health care professionals can offer individualized support to patients with MetS. A randomized controlled trial involving seven European countries reported that an internet-delivered intervention providing individualized nutrition advice yielded greater and more appropriate changes in dietary behaviour compared to non-individualized dietary advice [Citation61]. Moreover, given that our study followed a comprehensive behavioural change intervention framework, the individualized WeChat mini program-based diet intervention will be promising in improving dietary adherence, thereby improving metabolic parameters and quality of life in individuals with MetS. However, whether the intervention works will be tested in the intervention trial.

Strengths

To date, there has been no study conducted to develop a systematic and individualized WeChat mini program-based diet intervention for adults with MetS using the BCW in a Chinese context. Specifically, the present study was performed following a strong theoretical underpinning, which contributed to a better understanding the behavioural change process [Citation62] and uncovering positive effects [Citation63]. The lack of a theoretical foundation is related to the limited effectiveness of interventions. While multiple behavioural models abound, the majority fail to assist in designing interventions or understanding behavioural change processes. The present research aims to address this gap by applying the BCW. An additional strength inherent in the present study is its deliberate adoption of a qualitative research design to explore in depth the determinants influencing the target behaviour. As a result, health care professionals could develop more comprehensive behavioural change intervention strategies. These barriers and facilitators also provided references for other studies exploring dietary adherence. Finally, the current study successfully addresses the limitations observed in previous studies, including limited individualized elements, time-consuming, high costs, and a lack of real-time feedback, by incorporating more individualized elements and utilizing a digital intervention. In the future, our research team will refine and upgrade the WeChat mini program and conduct a controlled intervention trial to demonstrate its impact on dietary adherence. The trial study has been registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2100043877). If proven effective, health care professionals could offer the WeChat mini program to individuals with MetS in China, aiming to enhance dietary adherence and ultimately enhance their lives in China.

Limitations

However, this study also presents some weaknesses. First, all the participants were from Zhejiang Province. Although data saturation was attained, the applicability of this study to other contexts is limited. Future research will recruit more participants in different districts. Moreover, when the intervention designers used the BCW, subjectivity existed in the process of identifying the intervention content, such as using APEASE criteria. Therefore, subjectivity is a potential problem. Future research could address this issue by inviting a multidisciplinary team to participate in the process of developing interventions to obtain a wider range of views and suggestions. Additionally, given that some same BCTs were categorized to different IFs, their selection was challenging. Finally, the utilization of the BCW in the development of the WeChat mini program-based behavioural change intervention offers a systematic, theory-driven, and evidence-based approach, but the intervention design process was lengthy and time-consuming, which could potentially limit the efficiency of use.

Conclusions

Adherence to dietary recommendations is important, as it may predict the likelihood of MetS components and the risk of complications. This study outlined how an intervention to increase adherence to dietary recommendations in people with MetS was developed with the use of the BCW. In our study, an individualized WeChat mini program-based behavioural change intervention may increase adherence to dietary recommendations among individuals with MetS. Moving forward, our research team will refine and upgrade the WeChat mini program and then test the usability and effectiveness of the individualized WeChat mini program-based behavioural change intervention program.

Authors contributions

Dandan Chen: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing. Jing Shao: Conceptualization, formal analysis, writing-review & editing. Hui Zhang: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis. Jingjie Wu: Conceptualization, revising the article. Erxu Xue: Methodology, writing-review & editing. Pingping Guo: Methodology, writing-review & editing. Nianqi Cui and Xiyi Wang: Data curation. Liying Chen and Zhihong Ye: The conception and design of the study, validation, supervision, formal analysis, writing - review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript and Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate the participating hospital and all individuals with MetS who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and analysed in this study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns. However, they can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the international diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; national heart, lung, and blood institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the study of obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644.

- Saklayen MG. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20(2):12. doi: 10.1007/s11906-018-0812-z.

- Nolan PB, Carrick-Ranson G, Stinear JW, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic syndrome components in young adults: a pooled analysis. Prev Med Rep. 2017;7:211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.07.004.

- Yao F, Bo Y, Zhao L, et al. Prevalence and influencing factors of metabolic syndrome among adults in China from 2015 to 2017. Nutrients. 2021;13(12):4475. doi: 10.3390/nu13124475.

- Engin A. The definition and prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;960:1–17.

- Gallardo-Alfaro L, Bibiloni M, Mascaró CM, et al. Leisure-Time physical activity, sedentary behaviour and diet quality are associated with metabolic syndrome severity: the PREDIMED-Plus study. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):1013. doi: 10.3390/nu12041013.

- WHO. Global status on noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Association CPM, Branch of Heart Disease Prevention and Control CPMA, Society CD, Branch of Stroke Prevention and Control CPMA, Society CHM, Branch of Non-communicable Chronic Disease Prevention and Control CPMA, Branch of Hypertension CIEA, China CHAO. Chinese guideline on healthy lifestyle to prevent cardiometabolic diseases. Chin J Prev Med. 2020;54(3):256–277.

- Pérez-Martínez P, Mikhailidis DP, Athyros VG, et al. Lifestyle recommendations for the prevention and management of metabolic syndrome: an international panel recommendation. Nutr Rev. 2017;75(5):307–326. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nux014.

- Chen D, Zhang H, Shao J, et al. Determinants of adherence to diet and exercise behaviours among individuals with metabolic syndrome based on the capability, opportunity, motivation, and behaviour model: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nur. 2022;22(2):193–200.

- Zheng X, Yu H, Qiu X, et al. The effects of a nurse-led lifestyle intervention program on cardiovascular risk, self-efficacy and health promoting behaviours among patients with metabolic syndrome: randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;109:103638. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103638.

- George ES, Gavrili S, Itsiopoulos C, et al. Poor adherence to the mediterranean diet is associated with increased likelihood of metabolic syndrome components in children: the healthy growth study. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(10):2823–2833. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021001701.

- Montemayor S, Mascaró CM, Ugarriza L, et al. Adherence to mediterranean diet and NAFLD in patients with metabolic syndrome: the FLIPAN study. Nutrients. 2022;14(15):3186. doi: 10.3390/nu14153186.

- Tran VD, Lee AH, Jancey J, et al. Physical activity and nutrition behaviour outcomes of a cluster-randomized controlled trial for adults with metabolic syndrome in vietnam. Trials. 2017;18(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1771-9.

- Kay M, Santos J, Takane M. mHealth: new horizons for health through mobile technologies. Vol. 64. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. p. 66–71.

- Müller AM, Alley S, Schoeppe S, et al. The effectiveness of e-& mHealth interventions to promote physical activity and healthy diets in developing countries: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phy. 2016;13(1):109.

- Schoeppe S, Alley S, Van Lippevelde W, et al. Vandelanotte C: efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phy. 2016;13(1):127.

- Sequi-Dominguez I, Alvarez-Bueno C, Martinez-Vizcaino V, et al. Effectiveness of mobile health interventions promoting physical activity and lifestyle interventions to reduce cardiovascular risk among individuals with metabolic syndrome: systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e17790. doi: 10.2196/17790.

- Chen D, Ye Z, Shao J, et al. Effect of electronic health interventions on metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj Open. 2020;10(10):e36927. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-036927.

- Ordovas JM, Ferguson LR, Tai ES, et al. Personalised nutrition and health. BMJ. 2018;361:bmj.k2173. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2173.

- Wang Q, Chair SY, Wong E, et al. Actively incorporating lifestyle modifications into daily life: the key to adherence in a lifestyle intervention programme for metabolic syndrome. Front Public Health. 2022;10:929043. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.929043.

- Lau Y, Chee D, Chow XP, et al. Personalised eHealth interventions in adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Prev Med. 2020;132:106001. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106001.

- Azar KM, Koliwad S, Poon T, et al. The electronic CardioMetabolic program (eCMP) for patients with cardiometabolic risk: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(5):e134. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5143.

- Oh B, Cho B, Han MK, et al. The effectiveness of mobile Phone-Based care for weight control in metabolic syndrome patients: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(3):e83. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4222.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655.

- Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, et al. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol. 2008;57(4):660–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x.

- Michie S, West R, Campbell R. ABC of behaviour change theories. London: Silverback; 2014.

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

- Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel—a guide to designing interventions. Great Britain: Silverback; 2014.

- Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37.

- Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6.

- Cao W, Guo Y, Ping W. Development and psychometric tests of a chinese version of the HPLP-II scales. Chin J Dis Control Prev. 2016;3(20):286–289.

- Sullivan-Bolyai S, Bova C, Harper D. Developing and refining interventions in persons with health disparities: the use of qualitative description. Nurs Outlook. 2005;53(3):127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.005.

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388.

- Quinn PM. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. California: Sage; 2002.

- Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health. 2010;25(10):1229–1245. doi: 10.1080/08870440903194015.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Milne J, Oberle K. Enhancing rigor in qualitative description: a case study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2005;32(6):413–420. doi: 10.1097/00152192-200511000-00014.

- Cane J, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. From lists of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) to structured hierarchies: comparison of two methods of developing a hierarchy of BCTs. Br J Health Psychol. 2015;20(1):130–150. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12102.

- Davidson KW, Goldstein M, Kaplan RM, et al. Evidence-based behavioral medicine: what is it and how do we achieve it? Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(3):161–171. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2603_01.

- Fappa E, Yannakoulia M, Pitsavos C, et al. Lifestyle intervention in the management of metabolic syndrome: could we improve adherence issues? Nutrition. 2008;24(3):286–291. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.11.008.

- Fappa E, Yannakoulia M, Ioannidou M, et al. Telephone counseling intervention improves dietary habits and metabolic parameters of patients with the metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Rev Diabet Stud. 2012;9(1):36–45. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2012.9.36.

- Magkos F, Yannakoulia M, Chan JL, et al. Management of the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes through lifestyle modification. Annu Rev Nutr. 2009;29(1):223–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-080508-141200.

- Grundy SM, Brewer HJ, Cleeman JI, et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109(3):433–438. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6.

- Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404.

- Bach-Faig A, Berry EM, Lairon D, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(12A):2274–2284. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011002515.

- Fabiani R, Naldini G, Chiavarini M. Dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome in adult subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2019;11(9):2056. doi: 10.3390/nu11092056.

- Zhang X, Li Y, Wang J, et al. Effectiveness of digital guided self-help mindfulness training during pregnancy on maternal psychological distress and infant neuropsychological development: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e41298. doi: 10.2196/41298.

- Wang Q, Chair SY, Wong EM, et al. Metabolic syndrome knowledge among adults with cardiometabolic risk factors: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(1):159.

- Nicklas TA, Jahns L, Bogle ML, et al. Barriers and facilitators for consumer adherence to the dietary guidelines for americans: the HEALTH study. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(10):1317–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.05.004.

- Maas J, Hietbrink L, Rinck M, et al. Changing automatic behavior through self-monitoring: does overt change also imply implicit change? J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2013;44(3):279–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2012.12.002.

- Laiou E, Rapti I, Markozannes G, et al. Social support, adherence to mediterranean diet and physical activity in adults: results from a community-based cross-sectional study. J Nutr Sci. 2020;9:e53. doi: 10.1017/jns.2020.46.

- Beck AL, Iturralde E, Haya-Fisher J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to healthy eating among low-income latino adolescents. Appetite. 2019;138:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.04.004.

- Timlin D, McCormack JM, Simpson EE. Using the COM-B model to identify barriers and facilitators towards adoption of a diet associated with cognitive function (MIND diet). Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(7):1657–1670. doi: 10.1017/S1368980020001445.

- Muñoz TM, Cruz RS, Takahashi T. Self-control in intertemporal choice and mediterranean dietary pattern. Front Public Health. 2018;6:176. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00176.

- Howatt BC, Muñoz TM, Cruz RS, et al. A new analysis on self-control in intertemporal choice and mediterranean dietary pattern. Front Public Health. 2019;7:165. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00165.

- Curtis K, Lebedev A, Aguirre E, et al. A medication adherence app for children with sickle cell disease: qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(6):e8130. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.8130.

- Curtis KE, Lahiri S, Brown KE. Targeting parents for childhood weight management: development of a theory-driven and user-centered healthy eating app. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(2):e69. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3857.

- Rohde A, Duensing A, Dawczynski C, et al. An app to improve eating habits of adolescents and young adults (challenge to go): systematic development of a theory-based and target group-adapted mobile app intervention. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(8):e11575. doi: 10.2196/11575.

- Mummah SA, King AC, Gardner CD, et al. Iterative development of vegethon: a theory-based mobile app intervention to increase vegetable consumption. Int J Behav Nutr Phy. 2016;13:90.

- Celis-Morales C, Livingstone KM, Marsaux CF, et al. Effect of personalized nutrition on health-related behaviour change: evidence from the Food4Me european randomized controlled trial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(2):578–588. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw186.

- Patton DE, Hughes CM, Cadogan CA, et al. Theory-Based interventions to improve medication adherence in older adults prescribed polypharmacy: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2017;34(2):97–113. doi: 10.1007/s40266-016-0426-6.

- Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, et al. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(1):e4. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1376.