Abstract

Objective To explore the heterogenous subtypes and the associated factors of health literacy among patients with metabolic syndrome.

Methods A cross-sectional study was conducted, and 337 patients with metabolic syndrome were recruited from Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital in Zhejiang Province from December 2021 to February 2022. The Social Support Questionnaire, Short version of the Health Literacy Scale European Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q16), and MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status were used for investigation. Latent class analysis (LCA) was performed to explore the heterogenous subtypes of health literacy among Metabolic syndrome patients. Univariate analysis and logistic regression were used to identify the predictors of the latent classes.

Results The findings of LCA suggested that three heterogeneous subtypes of health literacy among individuals with metabolic syndrome were identified: high levels of health literacy, moderate levels of health literacy, and low levels of health literacy. The multinomial logistic regression results indicated that compared with low levels of health literacy class, the high levels of health literacy class were predicted by age (OR 0.932, 95%CI[0.900-0.966]), socio-economic status (OR 1.185, 95%CI[1.058–1.328]), and social support (OR 1.065, 95%CI[1.012–1.120]). Compared with low levels of health literacy class, the moderate levels of health literacy class were predicted by age (OR 0.964, 95%CI[0.934–0.995]), socio-economic status (OR 1.118, 95%CI[1.006–1.242]), male (OR 0.229, 95%CI[0.092–0.576]).

Conclusion The levels of health literacy among patients with metabolic syndrome can be divided into three heterogenous subtypes. The results can inform policy-makers and care professionals to design targeted interventions for different subgroups among patients with metabolic syndrome who are male, at older age, have less social support, and with disadvantaged socio-economic status to improve health literacy.

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) refers to a cluster of metabolic risk factors; this syndrome consists of abdominal obesity, lipid disorders (increased triglycerides and reduced high-density lipoprotein), elevated blood pressure, and elevated fasting blood glucose levels [Citation1].It has been estimated that the prevalence of MetS worldwide was 38% among adults [Citation2], and the prevalence of MetS was 33.9% in China [Citation3]. Evidence has indicated that MetS increases the risk of developing diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Individuals with MetS are approximately twice as likely to suffer cardiovascular disease and five times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes resulting in a high mortality rate [Citation4]. Currently, MetS has become one of the leading global public health challenges due to its epidemiological and economic burden [Citation5].

It is suggested that healthy lifestyles have been the first-line intervention for prevention as well as management of MetS [Citation6]. Healthy lifestyles refer to certain health behaviors such as a healthy diet, weight management, increased physical activity level, cessation of smoking or drinking, etc. Studies revealed that it was effective to be engaged in multi-disciplinary lifestyle modification programs to reduce one’s individual risk for MetS [Citation7].

Lifestyle modification as non-pharmacological measures are crucial to prevent the progression of the MetS and reduce the epidemic of MetS. Long-term adherence to lifestyle modification is of paramount importance for the successful management and prevention of MetS. However, research suggested that individuals with MetS were less successful in maintaining long-term health promotion behaviors and showed low adherence to diet and physical activity recommendations [Citation8]. This was mainly attributed to receiving confusing advice and information from a variety of sources and encountering several barriers that result in a loss of pleasure and autonomy in health promotion behaviors. Under this perspective, it has been suggested that long-term engagement in lifestyle modification is largely related with higher levels of health knowledge which can also be conceptualized as health literacy [Citation9].

Sørensen et al. have clearly stated the widespread definition that ‘health literacy is linked to literacy and entails people’s knowledge, motivation and competences to access, understand, appraise, and apply health information in order to make judgments and take decisions in everyday life concerning healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion to maintain or improve quality of life during the life course’ [Citation10]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), health literacy has been regarded as one of the most crucial health indicators. Individuals with low health literacy usually have difficulty in seeking health care, understanding health information, and following health instructions properly, which can lead to repeated hospitalizations, health inequalities, and substantial costs for patients [Citation10]. In this respect, health literacy plays a significant role in improving people’s access to health information, and increasing their capacity of searching health-related resources, so people can effectively understand and adopt healthy lifestyles to reduce the risks associated with MetS or actively promote their health.

In order to develop effective interventions promoting health literacy among individuals with MetS, knowledge on the determinants of health literacy in this population is necessary. Previous studies have explored the relationships between sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, socioeconomic status, and health literacy among individuals with MetS. For example, Krijnen et al. found that education, income, and occupational prestige were positive associated with health literacy among individuals with MetS [Citation11]. Research also suggested that gender and family history were related to health literacy among MetS population [Citation12].

Social support refers to receiving actual or perceived support offered from individual’s social networks, such as spouses, friends, co-workers, and families [Citation13]. It has been suggested that low social support was associated with poor health literacy in patients with hypertension [Citation14]. Previous research has also stated that social support is related to health literacy and is a critical target for the improvement of health outcomes among old adults and university students [Citation15,Citation16]. However, the relationships between social support and health literacy among MetS population have not been explored yet.

The above-mentioned studies have paved the way to examining the relationships between gender, education, income, and health literacy, but they usually evaluated health literacy based on the total scores of the self-assessment scales as the standard towards categorizing the literacy of individuals with MetS. Although this variable-centered approach is useful to study the general trends, it can lead to an oversight on the possibility that different heterogenous subgroups may share the same levels of health literacy within the group. Person-centered methods can be adopted to reveal the heterogeneity among subgroups which share similar characteristics [Citation17]. Compared to traditional, variable-centered approaches, latent class analysis (LCA) uses a person-centered approach to identify subgroups characterized by similar levels of health literacy.

To fill in significant gaps within research, this present study aimed to perform a latent class analysis to identify heterogenous subtypes of health literacy among individuals with MetS. We also wanted to identify sociodemographic characteristics and social support as predictors that may contribute to differences in health literacy among heterogenous subgroups. This study would be helpful to better differentiate and understand heterogenous subtypes of health literacy among individuals with MetS. This knowledge may be important to develop tailored health literacy intervention programs and policies to improve health outcomes in populations with MetS.

Methods

Design and participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted, and 368 individuals with MetS were recruited from the health promotion center of a hospital in Zhejiang Province from December 2021 to February 2022. We selected the specific hospital mainly attributed of convenience. The inclusion criteria for participants were the following: (1) age older than 18 years old; (2) diagnosed with MetS (Joint Scientific Statement harmonizing criteria 2009); (3) being capable of and willing to participate and complete study questionnaires on their own. The exclusion criteria were: (1) pregnant and breastfeeding women; (2) and individuals with neurological or mental disorders. Paper questionnaires were sent to participants through face-to-face interviews.

Before present study begins and frequently during the study, researchers discuss with participants about ethical principles, including confidentiality, anonymity and the right to participate or withdraw from the study. All participants were informed of the purpose of this present study. By doing this, participants are fully aware of their rights and the voluntary nature of the study increasing the probability of participating. Informed consent was obtained before distribution of the questionnaires. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethics committees of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital have approved the present study (20200115-31).

Measures

Sociodemographic data included age, gender, education and years of work experience, etc.

Health literacy

The Short version of Health Literacy Scale European Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q16) was used to evaluate health literacy [Citation18]. This questionnaire contains 3 dimensions of health literacy (health care, disease prevention, and health promotion) and 16 items. Each item was measured on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4 (very easy, easy, difficult, and very difficult). A sum score is calculated from 16 to 64 and higher scores mean greater health literacy. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.81.

Socio-economic status

The MacArthur Scale of Subjective Socio-economic status developed by Adler et al. was used to measure socioeconomic status [Citation19]. This scale could capture an individual’s reflection on current circumstances, background variables, and future opportunities. The scale asks the ‘following: At the top of the ladder are the people who have the most money, the most education, and the most respected jobs. At the bottom are the people who have the least money, least education, and the least respected jobs or no jobs’. There are two symbolic ladders with 10 numbered rungs in this scale where respondents are asked to subjectively indicate their own social standing. The total scores range from 0 to 20, and the higher scores present higher socio-economic status.

Social support

The Social Support Rating Scale developed by Xiao et al. was used to measure social support, and it can assess received support and perceived support from life (e.g. partners, colleagues, and supervisors). The scale consists of three dimensions: objective support, subjective support, and the usage of support [Citation20]. This scale Example items include: ‘In the past, when you encounter difficulties, what is the source that you ever received either economic support or practical problem-solving help?’, ‘How many intimate friends do you have, from whom you can receive support and help?’, and ‘What is the way of seeking help when you are in trouble?’. Each item was measured on 4-point Likert scales. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.706.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for the main variables. Latent class analysis was performed using Mplus7.4 to explore the heterogenous subtypes of the health literacy among MetS patients. For the present study, five latent class models were fitted to determine the optimal number of latent classes. The optimal number of classes was chosen based on a series of model fit statistics and the interpretability of the clusters. The model fit statistics included the Akaike information criterion (AIC), Schwarz’s Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and the sample-size-adjusted BIC (A-BIC), and the lower information criterion indicate a better model fit. Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR-LRT), bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT), and entropy were also selected as model fit statistics. Significant LMR and BLRT could help evaluate whether a k-class model is better than a k-1 class model. The entropy presents classification accuracy, and an entropy value close to 1 indicates better accuracy. After identifying the best-fitting profile solution, each participant was assigned to a most likely heterogenous subtype based on their posterior class probability. Sociodemographic characteristics, socio-economic status, and social support were compared between groups using Chi-square tests and F-tests. When testing multiple hypothesis, the Scheffe correction was used. Significant variables were included in multinomial logistic regression to explore the correlates of associated factors with subtypes. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Forest plot was drawn using the R software based on the results of multinomial logistic regression.

Results

Latent class analysis

A total of 337 participants completed the questionnaires. To identify the heterogenous subtypes of health literacy among MetS patients, an LCA was performed on the entire sample using three indicator variables (health care, disease prevention, and health promotion). The results of LCA () indicated that BLRT were all significant for the one- to five-class solutions. However, LMR-LRT suggested that the 2-class and the 3-classes were better than the 4-class and 5-class, respectively. Models with three classes showed lower AIC, BIC, and A-BIC than models with 2- and 3-classes. Moreover, entropy values in three-class solutions were slightly higher than in two-class solutions. Therefore, the 3-class solutions were chosen to be the best fit to the data based on a series of model fit statistics.

Table 1. Model fit results of latent classes for health literacy among patients with MetS.

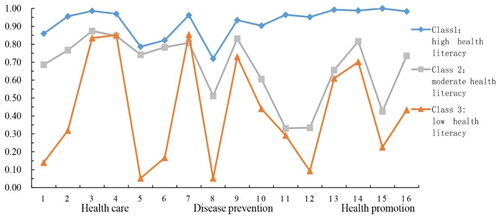

shows the mean scores of three dimensions of health literacy (health care, disease prevention, and health promotion) for all 16 items of the Health Literacy Scale. The y-axis represents the probability of all 16 items of Health Literacy Scale, while the x-axis represents items used for the latent class analysis. The three lines showed different health literacy patterns for the three subtypes. The first class (n = 110) was labeled as high levels of health literacy representing individuals with the highest scores in three dimensions of health literacy (health care, disease prevention, and health promotion) within 16 items. The second class (n = 135) was labeled as moderate levels of health literacy representing individuals with moderate scores in three dimensions of health literacy (health care, disease prevention, and health promotion). The third class (n = 92) was labeled as low levels of health literacy representing individuals with the lowest scores in 3 dimensions of health literacy (health care, disease prevention, and health promotion).

Exploration of factors associated with different latent classes

Differences in sociodemographic, socio-economic status, and social support between different latent classes are shown in . The findings suggested that gender, living areas, education, drinking, age, socio-economic status, and social support were significantly different across the three latent classes (p < 0.05). The classes did not differ significantly in terms of nationality, marital status, religion and smoking. The significant variables were included in the next multinomial logistic regression analysis.

Table 2. Differences in sociodemographic, socio-economic status, and social support between different latent classes.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis

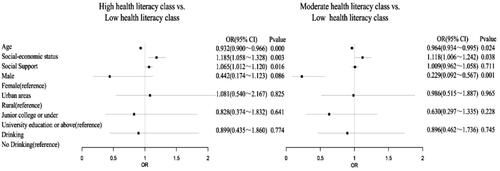

Multinomial logistic regression analysis was used to further identify the predictors distinguishing differences between three latent classes. Low levels of health literacy was set as the reference group, and the predictors were examined. As shown in , compared with low levels of health literacy class, the high levels of health literacy class was predicted by age (OR 0.932, 95%CI[0.900–0.966]), socio-economic status (OR 1.185, 95%CI[1.058–1.328]), and social support (OR 1.065, 95%CI[1.012–1.120]). Compared with low levels of health literacy class, the moderate levels of health literacy class was predicted by age (OR 0.964, 95%CI[0.934–0.995]), socio-economic status (OR 1.118, 95%CI[1.006–1.242]), male(OR 0.229, 95%CI[0.092–0.576]).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first study to investigate heterogenous subtypes of health literacy among individuals with MetS using LCA. Three heterogenous subtypes of health literacy in the population were identified, namely high levels of health literacy, moderate levels of health literacy, and low levels of health literacy, respectively. In addition, the difference between the subgroups was confirmed through multinomial logistic regression analysis, and the low levels of health literacy group was set as the reference group. The results indicated that gender, age, socio-economic, and social support were the predictors of heterogenous subtypes of health literacy among individuals with MetS.

The proportion of low levels of health literacy group was 27.3%, and individuals within this group had the lowest probability of engaging in health care, disease prevention, and health promotion. Meanwhile, the individuals in this subgroup usually had difficulty in accessing, understanding, appraising, and applying health information. While the proportion of low levels of health literacy group was small in this study, given the critical need to improve health outcomes by increasing health literacy amongst individuals with MetS, attention should nevertheless be paid to these individuals. It is suggested that policymakers should not only focus on providing infrastructure and facilities but also adopting programs to help people with low levels of health literacy explore, understand, and use existing access and resources to improve their health outcomes [Citation21]. The proportion of high levels of health literacy group was 32.6%. However, the largest proportion of participants fell into the moderate levels of health literacy (40.1%). Participants in the group with moderate levels of health literacy had moderate capacity in health care, disease prevention, and health promotion. It is important for healthcare providers to pay attention to participants in the group of moderate levels of health literacy because there was potential space to increase their ability to make appropriate health-related decisions and improve their health outcomes.

We found that being old was associated with a higher probability of being a members of the low levels of health literacy class. This means that age was an important risk factor for health literacy. Our results were similar to a previous study. Vogt et al. found that the levels of health literacy in adults over 65 years old are much lower than in adults between 50 and 64 years old, and almost three times lower than in younger age groups [Citation22]. This is probably because when people are getting old, an age-related change can happen during the cognitive processes which include poor capacity of comprehension, numeracy skills, problem-solving, information processing, and memory resulting in lower older adults’ ability to follow health care advice and recommendations and understand health guidance [Citation23]. Due to poor cognitive functions, old patients with MetS are not capable of obtaining and searching for information and resources leading to poor health literacy and failure to prevent and control diseases.

The findings indicated that socio-economic status was a crucial predictor in the present study. Compared to low levels of health literacy group, people with higher socio-economic status were more likely to be the members in the moderate and high levels of health literacy groups. This was in accordance with previous research [Citation24]. Svendsen et al. also found that disadvantaged socio-economic status resulted in low levels of health literacy [Citation25]. The socio-economic status consisted of the individual’s background variables (educational attainment, income, occupation) and future opportunities in our study, and it was particularly suggested that education was regarded as the most important determinant [Citation25]. This is because education has an effect on both employment status and income, which can allow people to gain access to vital resources such as better environmental conditions, healthy food and health insurance leading to high health literacy [Citation25].

Compared to the low levels of health literacy group, individuals with sufficient social support were more likely in the high levels of health literacy group. This means that social support was a protective predictor for health literacy in this study. Evidence has shown the similar effects of social support on health literacy. For example, Faiola et al. found that social support was significantly associated with health literacy among university students [Citation15]. Moreover, a previous study suggested that social support had a positive effect on health literacy, improving medication adherence among patients with hypertension [Citation14]. This is because sufficient social support from families, friends, peers, colleagues, and healthcare professionals can help patients read and understand health information [Citation26]. For example, individuals with MetS can have someone regularly reminding them to take medications and adopt healthy lifestyles and have someone take them to see a doctor if it is necessary. Moreover, patients could have a feeling of a greater sense of self-worth when receiving social support, which encourages them to be more optimistic and confident to receive treatment and care when facing physical, social and economic vulnerabilities [Citation27,Citation28]. Eventually, people with higher social support could have better health literacy and psychological and physical health.

Compared to the low levels of health literacy group, females are more likely to be members in the moderate levels of health literacy group. This indicated that low levels of health literacy were more prominent among males, and being male was a risk predictor of health literacy. Consistent with previous research, gender differences have always existed in the issues of health literacy. For example, Ganguli et al. found that females had significantly higher health literacy than male [Citation23]. This may be explained by the fact that women are more likely to pay attention to their health status, so they prefer to collect health-related information and resources than men leading to healthier lifestyles. Moreover, it is suggested that women are more active than men at obtaining information and resources from their healthcare providers, co-workers, friends, and published material in their daily lives to improve their health [Citation29], which can help them have better health literacy.

The findings from our study have important policy implications. Our results can help policy-makers and healthcare professionals identify those vulnerable groups that may be most in need of improving health literacy. Policy-makers should be aware of low and moderate levels of health literacy groups and develop targeted interventions for them. First, healthcare professionals should screen health literacy among individuals with MetS when tailoring their communications. Second, it is important to reduce the cognitive burden of health information and minimize the cognitive challenges among older patients with MetS. Third, standard health and safety information regarding health literacy should be designed. Lastly, more attention should be paid to patients with MetS who are older, male, with less social support, and with disadvantaged socio-economic status. Healthcare providers should find various resources to improve patients with MetS health literacy by enhancing health care knowledge, avoiding technical language, using more visual aids and figures, expanding educational or additional care coordination services, and providing medical assistance.

Limitations

This present study had several limitations to inform future research. First, this was a cross-sectional study, thereby it cannot infer a causal relationship. Longitudinal study design should be adopted in the future to explore trajectory and patterns changes of health literacy and the associated factors affecting it. Second, the instruments used in this study were all self-rating scales, so response bias and recall bias may show up. It might be helpful to take clinical measures of patients’ health literacy into account in the future. Third, although we aimed to identify the predictors of heterogenous subtypes of health literacy among individuals with MetS, the relationships between heterogenous subtypes of health literacy and self-care behaviors and health should be evaluated in the future.

Conclusion

The present study identified three heterogenous subtypes labeled as high levels of health literacy, moderate levels of health literacy, and low levels of health literacy among patients with MetS. The results also suggested that gender, age, socio-economic, and social support were important predictors of heterogenous subtypes of health literacy. For those vulnerable groups that may be most in need of improving health literacy, policymakers and healthcare providers should develop targeted interventions and programmes for them to reduce healthcare costs and improve health outcomes.

Authors’ contributions

HZ and XYW designed this present study, HZ, XYW and DDC collected data, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. HZ, XYW, DDC, JS, JJW, NQC, DJL, LWT, ZHY, EXX and PZ interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank research participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data is available upon a reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. MetS–a new world-wide definition. A consensus statement from the international diabetes federation. Diabet Med. 2006;23(5):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x.

- Saklayen MG. The global epidemic of the MetS. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20(2):12. doi: 10.1007/s11906-018-0812-z.

- Lu JL, Wang LM, Li M, et al. MetS among adults in China: the 2010 China noncommunicable disease surveillance. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2017;102(2):507–515.

- Bahar A, Kashi Z, Kheradmand M, et al. Prevalence of MetS using international diabetes federation, national cholesterol education panel- adult treatment panel III and iranian criteria: results of tabari cohort study. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2020;19(1):205–211. doi: 10.1007/s40200-020-00492-6.

- Solomon S, Mulugeta W. Disease burden and associated risk factors for MetS among adults in Ethiopia. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019;19(1):236. doi: 10.1186/s12872-019-1201-5.

- Zheng X, Yu H, Qiu X, et al. The effects of a nurse-led lifestyle intervention program on cardiovascular risk, self-efficacy and health promoting behaviours among patients with MetS: randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;109:103638. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103638.

- Peiris CL, van Namen M, O’Donoghue G. Education-based, lifestyle intervention programs with unsupervised exercise improve outcomes in adults with MetS. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2021;22(4):877–890. doi: 10.1007/s11154-021-09644-2.

- Magkos F, Yannakoulia M, Chan JL, et al. Management of the MetS and type 2 diabetes through lifestyle modification. Annu Rev Nutr. 2009;29(1):223–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-080508-141200.

- Emiral GO, Tozun M, Atalay BI, et al. Assessment of knowledge of MetS and health literacy level among adults in Western Turkey. Niger J Clin Pract. 2021;24(1):28–37. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_88_18.

- Sorensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-80.

- Krijnen HK, Hoveling LA, Liefbroer AC, et al. Socioeconomic differences in MetS development among males and females, and the mediating role of health literacy and self-management skills. Prev Med. 2022;161:107140. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107140.

- Froze S, Arif MT, R S. Determinants of health literacy and healthy lifestyle against MetS among major ethnic groups of Sarawak, Malaysia: a Multi-Group path analysis. TOPHJ. 2019;12(1):172–183. doi: 10.2174/1874944501912010172.

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310–357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310.

- Guo A, Jin H, Mao J, et al. Impact of health literacy and social support on medication adherence in patients with hypertension: a cross-sectional community-based study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023;23(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s12872-023-03117-x.

- Faiola A, Kamel Boulos MN, Bin Naeem S, et al. Integrating social and family support as a measure of health outcomes: validity implications from the integrated model of health literacy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;20(1):729.

- Lee S-YD, Arozullah AM, Cho YI, et al. Health literacy, social support, and health status among older adults. Educational Gerontology. 2009;35(3):191–201. doi: 10.1080/03601270802466629.

- Weller BE, Bowen NK, Faubert SJ. Latent class analysis: a guide to best practice. J Black Psychol. 2020;46(4):287–311. doi: 10.1177/0095798420930932.

- Storms H, Claes N, Aertgeerts B, et al. Measuring health literacy among low literate people: an exploratory feasibility study with the HLS-EU questionnaire. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):475. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4391-8.

- N A, A S-M, J S, al e. Social status and health: a comparison of British civil servants in Whitehall-II with european-and African-Americans in CARDIA. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(5):1034–1045.

- S X. The theoretical basis and application of social support questionnaire. J Clin Psychol Med. 1994;4(2):98–100.

- Bhusal S, Paudel R, Gaihre M, et al. Health literacy and associated factors among undergraduates: a university-based cross-sectional study in Nepal. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2021;1(11):e0000016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000016.

- Vogt D, Berens EM, Schaeffer D. [Health literacy in advanced age]. Gesundheitswesen. 2020;82(5):407–412. doi: 10.1055/a-0667-8382.

- Ganguli M, Hughes TF, Jia Y, et al. Aging and functional health literacy: a population-based study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(9):972–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.12.007.

- Svendsen MT, Bak CK, Sorensen K, et al. Associations of health literacy with socioeconomic position, health risk behavior, and health status: a large national population-based survey among danish adults. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):565. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08498-8.

- Stormacq C, Van den Broucke S, Wosinski J. Does health literacy mediate the relationship between socioeconomic status and health disparities? Integrative review. Health Promot Int. 2019;34(5):e1–e17. doi: 10.1093/heapro/day062.

- Yu H, Gao Y, Tong T, et al. Self-management behavior, associated factors and its relationship with social support and health literacy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. BMC Pulm Med. 2022;22(1):352. doi: 10.1186/s12890-022-02153-1.

- Morey BN, Valencia C, Park HW, et al. The Central role of social support in the health of chinese and korean American immigrants. Soc Sci Med. 2021;284:114229. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114229.

- Viseu J, Leal R, de Jesus SN, et al. Relationship between economic stress factors and stress, anxiety, and depression: moderating role of social support. Psychiatry Res. 2018;268:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.008.

- Loer AM, Domanska OM, Stock C, et al. Subjective generic health literacy and its associated factors among adolescents: results of a population-based online survey in Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):8682.