Abstract

Background

Botulism is a rare disease, and infant botulism (IB) even rarer, especially when steering the condition to honey consumption. IB is considered a life-threatening disease as it leads to severe neurological symptoms. Exploring the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) among mothers on the relationship between honey and IB will help public health professionals implement appropriate maternal health education materials targeting infant health and increase the awareness of the paediatric primary care providers, physicians, and nurse practitioners about the risk of IB among their patients.

Objectives

To determine the knowledge of mothers from Hail city in Saudi Arabia (SA) regarding IB and assess their attitude and practice towards feeding honey to their infants before 12 months of age.

Methods

Using a comparative cross-sectional study, in February 2022, we broadcasted an online questionnaire through social networking and evaluated the KAP of 385 mothers.

Results

Less than half (48%) of the mothers have heard about IB, 40% of them knew the relation between honey ingestion and IB and only 6.5% acknowledged that they knew the causative agent for IB. The prevalence of feeding honey to infants before 12 months was 52%. Mothers from Hail city were less likely to provide honey to their infants (p = 0.002).

Conclusion

The study revealed that mothers from Hail city have relatively low knowledge of IB and that they hold favourable perceptions of using honey as a food supplement and feeding honey to their infants before 12 months. Considering the high prevalence of honey feeding with the known low incidence of IB in SA, Medical professionals should consider IB in their differential diagnosis particularly in the presence of neurological symptoms.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Owing to the immaturity of their gut microflora [Citation1], infants are most susceptible to develop infant botulism (IB). Immobility of the intestines and a descending paralysis beginning with cranial nerve palsies progressing to respiratory failure [Citation2]. Moreover, symptoms such as hypotonia, constipation, facial diplegia, encephalopathy, seizures, and hypothermia make IB a life-threatening disease [Citation3]. Obviously, Clostridium botulinum is the causative agent since it appears to embody the disease name. However, what is surprising is the source of the organism, as it is linked to one of the most nutritious foods ever known to mankind, honey.

Honey is a well-known vehicle of C. botulinum spores and is considered an important food-related risk factor for IB. C. botulinum spores are spore-forming microorganisms that can survive in honey at low temperatures (4 °C). Botulism toxin affects peripheral nerve endings by blocking presynaptic acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junctions of skeletal muscles, which can result in the progressive decline of muscle function leading to flaccid paralysis. IB in infants results from spores’ germination in the intestine with in VIVO toxin production [Citation4,Citation5]. Honey samples collected from different parts of the world have tested positive for botulinum toxins [Citation4–9]. The association between IB and honey has been demonstrated in many studies [Citation4,Citation10,Citation11]. Evidence in the literature showed that honey consumption was associated with 15%–35% of the reported cases of IB. Accordingly, honey was advised to be omitted from infants’ diets, and its consumption and all foods supplemented with honey are banned for children under the age of 12 months [Citation4].

In a society as in Arab Islamic countries, where a vast majority of the population believes in complementary medicine and relies heavily on traditional systems of medicine, honey has been considered a miracle cure that spans a wide array of concerns, including promoting circulation; alleviating stomach, intestinal and colic pain; and acting as a topical antibiotic [Citation12]. In such a society, it is a challenge to convince people that honey can pose a health threat to infants and cause life-threatening diseases. What makes the situation even more challenging is that IB is relatively unknown in the community and people are barely aware that it exists. In reviewing the literature, we found only one reported case of IB in the Arabian Gulf States; from Al Kuwait, where the case was attributed to the consumption of commercially produced honey purchased from a local supermarket [Citation13]. On the other hand, countries like USA report their IB cases, for example, in the years of 1976–2016, around 1345 cases of infant botulism were reported in 45 of 58 California counties [Citation14]. This limitation of reported cases in Saudi Arabia does not, however, necessarily indicate the rarity of this disease in this area. Rather, they might indicate a lack of awareness and, consequently, underreporting due to a misdiagnosis, given that IB symptoms are varied and, in most cases, resemble other relatively common diseases, such as sepsis. To our knowledge, there are no studies conducted locally on IB or on honey-feeding practices among infants below 12 months of age in Saudi Arabia (SA). Knowing the prevalence of honey feeding to infants among Saudi mothers will help public health professionals implement appropriate maternal health education materials targeting infant health. It will also increase the awareness of paediatric primary care providers, physicians, and nurse practitioners about the risk of IB among their patients as well as alert researchers to the importance of conducting surveillance studies to determine the prevalence of IB in a community.

We conducted this study to investigate the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of honey feeding to infants below 12 months of age among mothers in Hail city. The aim was to explore defective areas of knowledge, misconceptions and feeding malpractices that need to be corrected.

2. Methods and material

2.1. Study design and period

This comparative cross-sectional study was conducted between 15 February and 15 March 2022.

2.2. Study area

The study was conducted using an online recruitment method, targeting Hail city in SA. Hail is the capital of Hail province, one of the 13 provinces of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), and is located in the northeast part of the kingdom. As of 2022, the population of Hail city was estimated as 310,897, and the total population of SA was 35.34 million. Non-Saudi expatriates represent approximately 30% of the total population, and 30% of the SA population is below 15 years of age [Citation15].

2.3. Study population

Saudi mothers who had at least one child aged more than 12 months at the time of the study, with emphasis on mothers living in Hail city.

2.4. Sample size

Using recent Saudi censuses and considering that our target population was adult Saudi females, the study population was calculated as 238,666 females of childbearing age living in Hail city. The online calculator (http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html) was used to calculate the sample size in this study. If the prevalence of honey feeding in the community is 50%, to get the maximum sample size with a 95% confidence level and acceptable p-value of 0.05, the sample size of the study was estimated as 385 participants. Therefore, when the survey reached this number online, we stopped receiving responses.

2.5. Data collection tool

The researcher developed a self-constructed questionnaire to obtain data on maternal KAP concerning IB and the use of honey. Following an extensive review of the literature, we designed a structured questionnaire to obtain relevant information from the respondents. The first version of the questionnaire was constructed in English and translated into Arabic. Back-translation into English was performed to ensure the accuracy and consistency of the tool. To evaluate data for tool verification, feasibility, clarity, and comprehensibility of the questionnaire, it was pretested on 10% of the sample size (38), which was not taken in the final study. The final version of the survey was presented in both Arabic and English languages. The questionnaire consisted of three main elements. The questionnaire was then distributed using the Internet such as Instagram, WhatsApp, and emails.

2.5.1. Element 1: Demographic data

This element included age, education, occupational status and monthly income. The questionnaire also included a question regarding the area of origin to ensure the mothers’ hometown.

2.5.2. Element 2: Baby feeding information

This element comprised a set of questions on the length of breastfeeding and the type and age of introducing supplementary food.

2.5.3. Element 3: Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding infant botulism

Maternal knowledge was assessed using questions about whether the mother knows the relation between honey consumption and IB, the name of the causative organism and a few symptoms of honey botulism.

The belief that honey is an important food supplement for infants and can cure some diseases was rated into scores using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) to indicate the degree of agreement.

The practice was determined by questioning whether mothers provide the infant with honey or honey-containing foods during the first year of life.

2.6. Data entry and analysis

The data were verified, coded, and entered into a personal computer. Categorical data were presented as frequency and percentage, while continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation. The study subjects were categorized into two groups based on the status of honey feeding (honey provider vs. non-honey provider), and then, analytic statistics were conducted using the chi-square test and Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Statistical significance was defined at the 5% level and analyses were all carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA Statistical Analysis).

2.7. Ethics and human subject’s issues

The institutional review board reviewed the study questionnaire and the study protocol, and approval was obtained from Umm Al-Qura University (HAPO-02-K-012-2021-10-799) before the questionnaire was distributed. Data were collected using an anonymous online survey. In addition, the questionnaire included a statement that guarantees data confidentiality and that it will be used exclusively for research purposes. A full explanation of the study aims was posted in the online questionnaire. Acceptance to answer the questionnaire was considered consent to participate in the research.

3. Results

3.1. Study group characteristics

There were 385 mothers who participated in this study, with the majority (36.9%) being between the ages of 26 and 35. The participants were primarily from Hail city, and the remaining half came from various parts of SA. A total of 63.1% of the participants were bachelor’s degree holders. A 55.6% of the participants work, with 22.6% involved in health care and education. Most families in the study sample (48.6%) had an income less than 5,000 Saudi Arabian riyal which is the most common average income in Saudi (SAR) ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics, sociodemographic educational, career and economic history, for the study population.

3.2. Knowledge, attitude, and practice

3.2.1. Knowledge

Less than half of the mothers (47.8%) have heard of IB, and only 41.6% know some symptoms. Likewise, only 36.9% of respondents knew that honey intake is linked to IB ().

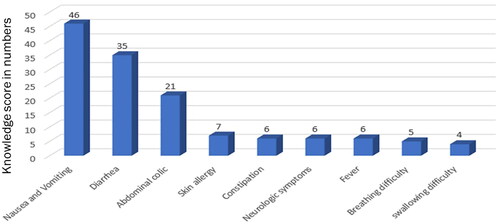

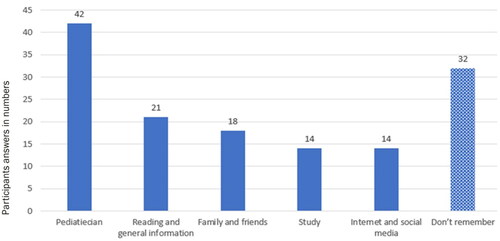

Nausea and vomiting are the most known symptoms of IB, while swallowing difficulties is the least known (). Out of 385 mothers, only 141 participants responded to the question concerning the source of information regarding IB. Forty-two (10.9%) of them obtained their information from a paediatric physician ().

3.2.2. Believes and attitudes

A total of 71 mothers (18.4%) and 65 mothers (16.9%) strongly disagreed that honey is an important food supplement and may treat gastrointestinal symptoms, respectively. The majority had a disagree answer: 98 mothers (25.5%) to the statement ‘I believe honey is an important food supplement’ and 108 mothers (28.1%) were neutral to the statement ‘I believe honey can treat GI symptoms’ ().

Table 2. Maternal knowledge concerning infant botulism, (n = 385).

Table 3. Proportions of participants in regard to believes towards honey.

3.3. Practice

3.3.1. Practice of honey feeding to infants before 12 months

Almost 52% were found to provide honey to their infants before 12 months of age, with the majority providing honey between 4 and 7 months (86, 42.6%).

3.3.2. Complementary feeding

The mean age of introduction of first complementary feeding for infants was 5.49 months SD ± 1.38. The majority (84.2%) started complementary food between 4 and 7 months.

3.4. Factors contributing to KAP

3.4.1. Effects of sociodemographic characteristics of mothers on feeding honey to their infants before 12 months

In this study, a statistically significant association between honey-feeding infants before 12 months of age and the sociodemographic features was found, including age groups, region of the KSA, educational level, mother’s occupation and family income. About 63.9% in the age group of 46–55 years and 66.7% above 55 years provided honey to their infants (p = 0.009).

Fewer mothers from Hail 86 (44.6%) provided honey to their infants compared to mothers from other regions of the kingdom 116 (60.4%) with (p = 0.002).

A higher proportion of mothers (61, 76.3%) with low educational level (high school or lower) provided honey to infants below 12 months, followed by mothers with a bachelor’s degree (115, 47.3%) with (p < 0.001).

Non-working mothers reported a higher prevalence of honey feeding than did working mothers (p = 0.003), and mothers with a family income less than 5,000 SAR were more likely to provide honey before 12 months than did mothers of other financial groups (p = 0.010) ().

Table 4. Sociodemographic characteristics as predictors for feeding of honey to infants before 12 months of age.

3.4.2. Effects of knowledge and beliefs of mothers on feeding honey to their infants before 12 months

Among mothers who provided honey to their infants, 162 mothers (75.0%) reported high scores for the question “I believe honey is a good food supplement,” and 168 mothers (74.0%) for the question “I believe honey is a good treatment for intestinal symptoms” (p < 0.001). On the other side, although the awareness of the relation of honey to IB, 33.8% were found to provide honey to their infants (p < 0.001).

Significant association was also found between age of complementary food and honey ingestion before 12 months, as 93 mothers who gave honey before age of 12 months started complimentary food before 6 months in comparison to only 57 mothers who didn’t, on the other hand only 9 mothers who gave honey before age of 12 months started complimentary food after 12 months in comparison to 14 mothers who did not (p = 0.009). However, no statistical relation was found regarding breastfeeding, (p > 0.05) ().

Table 5. Knowledge and behaviour as predictors for the prevalence of honey feeding to infants before 12 months.

4. Discussion

The current study is a cross-sectional study aimed at determining the KAP of mothers regarding honey feeding to their infants below 12 months of age. The study topic is rare, and the scarcity of literature is expected because botulism is a rare disease, and IB even rarer, especially when steering the condition to honey consumption. We found that studies on the KAP of mothers or caregivers regarding the association of honey to IB are even scarcer, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first KAP study of IB locally and worldwide.

Many researchers pointed out that parents are usually unaware of the potential danger of IB [Citation16]. In this study, more than half of the mothers (52%) were not aware of the risk of IB, and this was comparable to a survey undertaken to investigate mothers’ knowledge of the main foodborne agents and dietary regimens during pregnancy. Specifically, the mothers were asked about their awareness of botulism, and only 51% of the sample knew of the disease in infants [Citation17]. The low levels of knowledge among our study participants were even lower than the level reported in an Indian study, which found that only 25% of participants were unaware of the risks of IB [Citation18].

Further exploration of our data demonstrated that only 6.5% of mothers knew the causative agent for IB, and only 7.5% knew that IB could cause intestinal paralysis. Maternal answers about the symptoms and signs of IB revealed that mothers were not aware of the essential signs of IB, namely constipation and neurological problems in the form of partial muscle paralysis, breathing difficulty and swallowing difficulty, with only around 1% reported knowing these signs. However, we are certain that these are not biased answers because the mothers’ answers to the question of symptom and signs was an open-ended question rather than one that required a ‘YES’ or ‘NO’ response.

The largest source of information to mothers was the treating physician, emphasising the importance of physicians as health educators. Although family members are generally a good resource of information, the low proportion of mothers receiving the information from their family members may indicate the generally low level of knowledge about IB in the community.

In general, mothers showed favourable perceptions about honey, as their mean score for believing that honey is a good food supplement and a good treatment for intestinal symptoms was above average.

We found that older mothers are more likely to give honey to their babies. This practice is most probably related to their level of education, as we also found that mothers with less education and non-working mothers were more likely to give honey to their infants before 12 months.

In this study, the mean age of introduction of complementary food was less than 6 months. Although this age does not comply with the WHO recommendations for infant feeding [Citation19], the practice is still prevalent in many communities locally and nationally. The study ‘Assessment of the actual practices regarding breastfeeding and weaning among mothers in Al Madinah Al Munawarah’ revealed that 47.4% of the mothers introduced complementary feeding before 6 months [Citation20]. Alzaheb et al. likewise reported that 62.5% of the infants received solid foods before reaching 17 weeks of age [Citation21]. The high figure of 84.2% of mothers in our study who started complementary food between 4 and 7 months is comparable to a study conducted in the United Kingdom, which investigated parents’ knowledge, beliefs and practices concerning infants’ complementary feeding among different communities and found that most communities start complementary feeding before 6 months [Citation19]. In this study, the age pattern for feeding honey is very similar to the age pattern for starting complementary feeding, denoting that honey is given as part of complementary feeding.

Regarding therapy we did not find any written or followed guidelines in Gulf countries or Saudi Arabia regarding treating cases of IB. On the contrary countries like USA recommend starting antitoxins in severe cases, while supportive therapy is recommended for mild ones [Citation22]. Clinical diagnosis of botulism is usually confirmed by special laboratory testing that includes full blood counts, electrolytes, liver function tests, urine analysis, cerebrospinal fluid analysis and testing toxins in stool and urine or blood. Botulism treatment depends on the severity of the case, it can involve neutralizing the toxins with specific antitoxins or antibodies or taking supportive therapy until the body recovers [Citation22].

Information validity was ensured by giving the participants the free will to participate in the study, a point that reduced the chances of participants giving wrong information if they did not want to disclose any information. Furthermore, the research was conducted without the involvement of any personal elements to ensure the qualitative data obtained were relevant, reliable, and precise. Consistency of the study results with the existing literature in terms of demographics and feeding habits further assured the validity and reliability of this study. The consistency of our data was also verified by the significant association between maternal knowledge and beliefs and the practice of feeding honey before 12 months. Since literature review concerning this study topic is scarce, the results of this study will be a reference resource for future studies.

The main limitation of this study is the non-random sampling. Given that the study questionnaire was distributed through the social network, there was a greater probability of getting a response from mothers who have access to the Internet al.though the questionnaire involved questions about past practices, recall bias was not a problem in this study because mothers will remember feeding habits to their children as this is not a one-time act but rather an on-going, daily activity.

5. Conclusion

The low incidence of IB despite the high prevalence of honey feeding to infants may be due to under-recognition, underreporting or both. This situation should alarm medical professionals to consider IB treatment, particularly in the presence of neurological symptoms such as bulbar weakness, palsies or hypotonia. This study found that many mothers receive information concerning baby feeding from their doctors; thus, health care professionals, particularly paediatricians, need to concentrate on targeting health education. This study should be supported by other studies and publications on honey ingestion among infants to enhance the understanding of the disease and its incidence in SA.

Author contributions

All authors were equally involved in the conception, design, analysis, intervention, drafting, and revising the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statements

All data are available upon requested.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Harris R, Tchao C, Prystajecky N, et al. A summary of surveillance, morbidity and microbiology of laboratory-confirmed cases of infant botulism in Canada, 1979–2019. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2021;47(78):1–8. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v47i78a05.

- Midura TF. Update: infant botulism. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9(2):119–125. doi: 10.1128/CMR.9.2.119.

- Horvat DE, Eye PG, Whitehead MT, et al. Neonatal botulism: a case series suggesting varied presentations. Pediatr Neurol. 2023;146:40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2023.06.004.

- Arnon SS. Honey, infant botulism and the sudden infant death syndrome. West J Med. 1980;132(1):58–59.

- Dilena R, Pozzato M, Baselli L, et al. Infant botulism: checklist for timely clinical diagnosis and new possible risk factors originated from a case report and literature review. Toxins (Basel). 2021;13(12):860. doi: 10.3390/toxins13120860.

- Schwartz KL, Austin JW, Science M. Constipation and poor feeding in an infant with botulism. CMAJ. 2012;184(17):1919–1922. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.120340.

- Al-Waili N, Salom K, Al-Ghamdi A, et al. Antibiotic, pesticide, and microbial contaminants of honey: human health hazards. Scientific World J. 2012;2012:1–9. doi: 10.1100/2012/930849.

- Schocken-Iturrino RP, Carneiro MC, Kato E, et al. Study of the presence of the spores of Clostridium botulinum in honey in Brazil. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999;24(3):379–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01309.x.

- Nevas M, Hielm S, Lindström M, et al. High prevalence of Clostridium botulinum types a and B in honey samples detected by polymerase chain reaction. Int J Food Microbiol. 2002;72(1-2):45–52. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(01)00615-8.

- Abdulla CO, Ayubi A, Zulfiquer F, et al. Infant botulism following honey ingestion. BMJ Case Rep. 2012. doi: 10.1136/bcr.11.2011.5153.

- Midura TF, Snowden S, Wood RM, et al. Isolation of Clostridium botulinum from honey. J Clin Microbiol. 1979;9(2):282–283. doi: 10.1128/jcm.9.2.282-283.1979.

- Al-Rawi S, Fetters MD. Traditional Arabic and Islamic medicine: a conceptual model for clinicians and researchers. Glob J Health Sci. 2012;4(3):164.

- Van der Vorst MMJ, Jamal W, Rotimi VO, et al. Infant botulism due to consumption of contaminated commercially prepared honey. Med Princ Pract. 2006;15(6):456–458. doi: 10.1159/000095494.

- Panditrao MV, Dabritz HA, Kazerouni NN, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of infant botulism in California: the first 40 years. J Pediatr. 2020;227:247–257.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.08.013.

- GMI. SAUDI ARABIA POPULATION STATISTICS 2022 [Internet]. Global Media Insight. 2021. Available from: https://www.globalmediainsight.com/blog/saudi-arabia-population-statistics/.

- Tanzi MG, Gabay MP. Association between honey consumption and infant botulism. Vol. 22. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(11):1479–1483. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.16.1479.33696.

- Traversa A, Bianchi DM, Astegiano S, et al. Consumers’ perception and knowledge of food safety: results of questionnaires accessible on IzsalimenTO website. Ital J Food Saf. 2015;4(1):46–48.

- Sultania P, Agrawal NR, Rani A, et al. Breastfeeding knowledge and behavior among women visiting a tertiary care center in India: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Glob Health. 2019;85(1):64. doi: 10.5334/aogh.2093.

- Cook EJ, Powell FC, Ali N, et al. Parents’ experiences of complementary feeding among a United Kingdom culturally diverse and deprived community. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17(2):1–14.

- Salah El Gendy M. Assessment of the actual practices regarding breastfeeding and weaning among mothers in Al Madinah Al munawarah. J Food Sci Nutr Res. 2020;03(04):276–290. doi: 10.26502/jfsnr.2642-11000055.

- Alzaheb RA. Factors associated with the early introduction of complementary feeding in Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(7):702.

- Goldberg B, Danino D, Levinsky Y, et al. Infant botulism, Israel, 2007–2021. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29(2):235–241. doi: 10.3201/eid2902.220991.