Abstract

Objective

To investigate the outcome of total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) and postoperative pain characteristics and compare the pain severity after TLH for adenomyosis or uterine fibroids.

Methods

This prospective observational study collected 101 patients received TLH for adenomyosis (AD group) including 41 patients were injected goserelin (3.6 mg) 28 days before TLH, while other adenomyosis patients received TLH without preoperative treatment, and 113 patients received TLH for uterine fibroids (UF group). Pain scores were evaluated at different time sites from operation day to postoperative 72 h using the numeric rating scale. Clinical data were collected from clinical record.

Results

Operative time and anaesthetic time were longer in the AD group than those in the UF group (66.88 ± 8.65 vs. 64.46 ± 7.21, p = 0.04; 83.95 ± 10.05 vs. 79.77 ± 6.88, p < 0.01), severe endometriosis was quite more common in AD group (23.76% vs. 2.65%, p < 0.01). Postoperative usage of Flurbiprofen in AD group were more than that of UF group (15.48 ± 38.00 vs. 4.79 ± 18.16, p = 0.02). Total pains and abdominal visceral pains of AD group were more severe compared with UF group in motion and rest pattern at several time sites, while incision pain and shoulder pain were similar. The total postoperative pains after goserelin preoperative treatment in AD group were less than that without goserelin preoperative treatment (p < 0.05). The levels of serum NPY, PGE2 and NGF after laparoscopic hysterectomy of adenomyosis reduced with GnRH agonist pretreatment.

Conclusions

Acute postoperative pain for adenomyosis and uterine fibroids showed considerably different severity, postoperative total pain and abdominal visceral pains of TLH for adenomyosis were more severe compared with uterine fibroids. While patients received goserelin before laparoscopic hysterectomy of adenomyosis suffered from less severity of postoperative total pain than that without goserelin preoperative treatment.

Key messages

Acute postoperative pain for adenomyosis and uterine fibroids showed considerably different severity, postoperative total pain and abdominal visceral pains of TLH for adenomyosis were more severe compared with uterine fibroids.

Patients received goserelin before laparoscopic hysterectomy of adenomyosis suffered from less severity of postoperative total pain than that without goserelin preoperative treatment.

Introduction

Total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) is one of the most common gynaecological procedure; moreover, symptomatic uterine fibroids and adenomyosis are the main indications as benign diseases for hysterectomy [Citation1,Citation2]. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy is increasingly used, as this approach can reduce postoperative morbidity, ensure earlier recovery and a shorter postoperative hospital stay compared to open hysterectomy [Citation3,Citation4].

Although considered less painful than open abdominal hysterectomy, laparoscopic hysterectomy also requires suitable postoperative pain management timely to ensure shorter hospitalization and faster recovery, particularly in the early postoperative period. The timely detection and treatment of intense acute postoperative pain within the first three days is important, which may reduce the risk of developing chronic pain and increase the quality of life for patient [Citation5–7].

In addition to incision pain, TLH may cause different types of pain including abdominal pain, shoulder pain, etc, which results from various perioperative predicaments, including pneumoperitoneum, stretching of the abdominal cavity, and dissection of the pelvic region. Moreover, the severity and style of postoperative pain may also associate with different indications for total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Patients with severe dysmenorrhea undergoing laparoscopy for ectopic pregnancy may suffer from a high risk of substantial postoperative pain after gynaecological laparoscopy [Citation8].

To identify and predict acute postoperative pain after TLH is the first important step to manage it. While pain characteristics of laparoscopic hysterectomy associated with different indications are unclear and may differ from other gynaecological laparoscopies. Therefore, we designed the present study to investigate the pain characteristics and pain control after total laparoscopic hysterectomy for the indications of uterine fibroids and adenomyosis.

Methods

Patients and methods

This prospective observational study was approved by the ethics committee of Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital (NO.2021KY035) and it is a registered clinical study(ChiCTR2200060698). The study recruited patients who had undergone total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) due to adenomyosis or uterine fibroids. The patients were recruited from January 2021 to December 2021 in the Department of Gynecology, Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, Fujian Provincial Hospital and Tiantai branch of Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital. Detailed surgical and clinical data were collected from electronic medical records, and the pain intensity was assessed by the third party. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines for the Declaration of Helsinki. Verbal and written informed consents were obtained from all the included patients.

Patients scheduled for elective TLH under general anaesthesia due to adenomyosis or uterine fibroids were included in this study. The details of inclusion criteria were as follows: adenomyosis or uterine fibroids as the indication for hysterectomy diagnosed through preoperative ultrasound, age 18–55 years and American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification of I to II [Citation9]. The diagnostic criteria for adenomyosis included a myometrial lesion, a distorted and heterogeneous myometrial echotexture, and a globular and/or asymmetric uterus. All patients with symptoms of adenomyosis, such as dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, or menostaxis, were recruited in this study. Based on transvaginal ultrasound and gynaecological examination, patients with adenomyosis accompanied by deep infiltrating endometriosis were excluded from this study. One or two cycle of subcutaneous injections of goserelin (Zoladex 3.6 mg, AstraZeneca, UK) as preoperative treatment were performed for some patients before laparoscopic hysterectomy of adenomyosis.

The diagnostic criteria for uterine fibroids included a markedly enlarged uterus containing fibroid diagnosed by ultrasonography and with symptoms such as menorrhagia, frequent urination or other relative symptoms. The exclusion criteria were as follows: cancer, infection, smoking history, body mass index of >35 kg/m2, alcohol or drug use, chronic pain, or psychiatric disorders.

Surgical procedures

The anaesthesia management protocol was standardized among all patients. All patients were given a mask to inhale oxygen with a flow rate set at 6–8 L/min. Anaesthesia was induced using propofol (1.0–1.5 mg/kg), remifentanil (1.5 µg/kg), and cisatracurium (0.15–0.20 mg/kg). General anaesthesia was used to induce tracheal intubation after 3 min of assisted breathing. Anaesthesia was maintained with propofol (4–6 mg/kg/h) and remifentanil (0.2–0.4 µg/kg/min). The propofol infusion was titrated to maintain the bispectral index value between 40 and 60.

The surgical procedure consisted of a coincident total laparoscopic hysterectomy. The women were placed in the lithotomy position with the arms alongside the body. The intra-abdominal pressure was of 12 mmHg during the procedure. An umbilical trocar (12 mm) and two lower abdominal trocars (5 mm) were placed in lower abdomen on both sides and confirm them access the abdominal and pelvic cavities. A harmonic scalpel was used to cut the arteries and ligaments. Bipolar coagulation electrodes were used to manage bleedings. A harmonic scalpel was used for cutting the peritoneum and vaginal cuff. After transvaginal removal of the uterus, the vaginal cuff was sutured with barbed, delayed absorbable sutures using the intracorporeal knots technique. All the surgical procedures were performed by senior surgeons.

Postoperative pain was evaluated by the numeric rating scale (NRS; score range 0–10; 0, no pain; 10, worst imaginable pain) during the first 72h postoperatively. If the pain exceeded an NRS score of 4, intravenous flurbiprofen (1 mg/kg) was administered, and opioids were prepared as rescue analgesics postoperatively. Postoperative nausea or vomiting was treated with intravenous metoclopramide (10 mg). If metoclopramide was ineffective, ondansetron (4 mg) was administered.

Data collection

Patient demographic data, including age, body mass index, ASA physical status, clinical history, and preoperative diagnosis were recorded 1 day prior to the scheduled surgery. The volume of the uterus was also measured by transvaginal sonography. The volume of the uterus was calculated using the prolate ellipse equation (length × width × height × 0.523).

Surgical data such as surgical time, anaesthetic time, endometriosis severity, adhesions observed during laparoscopy, and drainage insertion were collected from the clinical record. Endometriosis severity was classified according to the American Society of Reproductive Medicine classification system and we defined stage I and stage II as mild, stage III and stage IV as severe. If the pelvic adhesion involved more than half of the pelvic cavity, we defined it severe; other is mild or no adhesion.

Serum neuropeptide Y (NPY), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and nerve growth factor (NGF) were detected by ELISA at 24h postoperatively for adenomyosis. The patients were preoperatively trained by researchers regarding the use of the NRS, and preoperative dysmenorrhea was assessed by the NRS. Postoperative pain was evaluated at the end of surgery and at 1, 3, 12, 24, 48, and 72h postoperatively. Postoperative pain was assessed using the NRS at motion (patients were told to cough) and at rest, which was described previously [Citation10]. NRS was categorized as low pain if in the range of 0 to 3 and high pain if in the range of 4 to 10. Adverse effects, such as nausea, vomiting, wound infection, delayed wound healing, and fever, were evaluated five days after the operation [Citation11].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean values and standard deviations, and categorical data was presented as counts and percentages. Before the two-sample t-test, data was confirmed to be normally distributed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. In addition, variables as age, BMI, and operation time were analysed using the two-sample t-test. Chi-square test was used to compare categorical data such as complications. If n < 5, the Fisher’s exact test was applied for categorical data. The continuous variables in the study were skewed distribution variables and were presented as the median with an interquartile range [M (P25–75)]. The SPSS 22.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to conduct the statistical analyses. Repeatedly measured data, including overall, incision, visceral, and shoulder pain, were analysed using a linear mixed model with compound symmetry; compare pain at rest and in motion, compare pain at each sites, and compare pain in two groups of different disease. Additionally, all statistical tests were two tailed and a p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Among 214 patients, 113 patients were diagnosed uterine fibroids (UF group) and 101 patients were diagnosed adenomyosis (AD group), all patients received TLH. All patients with adenomyosis were confirmed by postoperative uterine histopathology. After laparoscopy, no deep infiltrating endometriosis was found in this study. Patient characteristics and data from the preperative period are summarized in .

Table 1. Patient clinical characteristics and data of the patients.

Age, parity, body mass index (kg/m2), previous gynaecological surgical history, previous caesarean section did not show significant differences. About the preoperative symptoms, menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual abdominal pain of AD group were more severe than that of the UF group significantly (p < 0.05).

There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of postoperative hospital stay (day), rate of operative complications (visceral damage, postoperative infection, nausea, vomiting) and postoperative defecation. Operative time (min) and anaesthetic time (min) were longer in the AD group than in the UF group (66.88 ± 8.65 vs. 64.46 ± 7.21, p = 0.04; 83.95 ± 10.05 vs. 79.77 ± 6.88, p < 0.01), the blood loss of the AD group was more than that in the UF group significantly (106.67 ± 48.4 vs. 82.87 ± 34.69, p < 0.01). Pelvic adhesion and severity of endometriosis were evaluated during the operation, and we found that severe endometriosis was quite more common in the AD group (23.76% vs. 2.65%, p < 0.01) ().

Table 2. Clinical outcome and the information of the TLH.

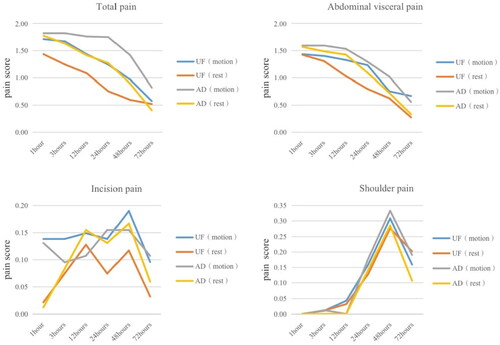

The total pain after TLH decreased gradually from operation day to postoperative 72h. After postoperative 48h, no patients ask for analgesia. Abdominal visceral pain dominated over other pain for postoperative 72h. Whereas shoulder pain was quite less on the day of operation and increased to the maximum severity from postoperative 12h to 48h, then the severity reduced gradually.

The total pains of AD group were higher than that of UF group, especially at 12 h after operation, on day 1, on day 2, and on day 3 (p < 0.05) in motion (.). The total pains of AD group were higher than that of UF group, especially from 1h after operation to day 2 (p < 0.05) in rest (). Postoperative usage of Flurbiprofen of AD group was more than that of UF group (15.48 ± 38.00 vs. 4.79 ± 18.16, p = 0.02) ().

Figure 1. Average postoperative pain score of total pain, abdominal visceral pain, incision pain and shoulder pain for postoperative 72 h of TLH.

Our study demonstrated abdominal visceral pains of adenomyosis were more severe compared with uterine fibroids in motion and rest pattern at several time-sites from operation day to postoperative 72h (). Incision pain and shoulder pain of AD group were similar to those of UF group in motion and rest pattern from operation day to postoperative 72h ().

Compare clinical information of patients with or without preoperative treatment, age, body mass index (kg/m2), previous gynaecological surgical history, previous caesarean section, menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, non-menstrual abdominal pain and postoperative usage of Flurbiprofen did not show significant differences.

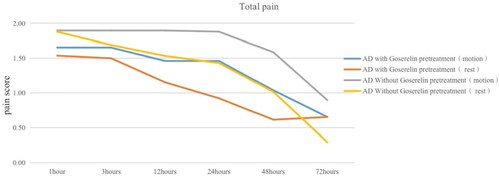

In the AD group, 41 patients received goserelin (Zoladex 3.6 mg, AstraZeneca, UK) as preoperative treatment before laparoscopic hysterectomy of adenomyosis. The total pain of goserelin preoperative treatment group was less than that without goserelin treatment at most time-sites from 1h after operation to day 3 in motion and rest pattern (p < 0.05) (). While incision pain and shoulder pain with or without pretreatment were similar in motion and rest pattern. The levels of serum NPY, PGE2 and NGF were higher at 24h after laparoscopic hysterectomy of adenomyosis without pretreatment than patients with pretreatment statistically significant (p < 0.01) ().

Table 3. Comparison of serum pain factor levels for adenomyosis with or without pretreatment.

Discussion

Postoperative pain after TLH is often neglected by clinician. Persistent uncontrolled pain may transform into chronic or neuropathic pain, and the postoperative pain may increase opioid use and delay discharge from hospital [Citation7,Citation12].

Laparoscopic hysterectomy requires standardized postoperative pain management, particularly in the early postoperative stage. The management of pain after laparoscopic hysterectomy can promote the postoperative recovery and has attracted many scholars’ attention to take various rapid recovery treatments [Citation13,Citation14]. This prospective observational study described the pain characteristics during the first postoperative 72 h in patients undergoing TLH for adenomyosis or uterine fibroids. The postoperative pain includes incision pain, visceral pain, and shoulder pain commonly. Incision pains and visceral pains are surgical trauma pains. Surgical trauma induces the local and systemic inflammatory state by the local release of inflammatory proteins and cytokines, which enter the circulation and systemically spread [Citation12]. So far laparoscopy-induced shoulder pain is generally considered as referred pain. Rapid carbon dioxide (CO2) pneumoperitoneum and the head-down position may be followed by overstretching of the diaphragmatic muscle fibres, tearing of blood vessels, traumatic traction of nerves, or release of inflammatory mediators [Citation15,Citation16].

In this study, the total pain after TLH decreased gradually from operation day to postoperative 72 h. After postoperative 48 h, no patients ask for analgesia. Abdominal visceral pain dominated over other pain from the day of operation to postoperative 72 hr. Whereas shoulder pain was quite less on the day of operation and increased to the maximum severity from postoperative 12 h to 48 h, then the severity reduced gradually.

Considering that Flurbiprofen shows antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis, and prostaglandins are highly potent inflammatory mediators and pain-inhibited factors [Citation17]. We used Flurbiprofen as the first line postoperative analgesia and find that postoperative usage of Flurbiprofen of AD group was more than that of UF group (15.48 ± 38.00 vs. 4.79 ± 18.16, p = 0.02). Our study demonstrated overall pain and abdominal visceral pains of adenomyosis were more severe compared with uterine fibroids in motion and rest pattern at several time sites from operation day to postoperative 72 h.

Adenomyosis is a common gynaecological disorder characterized by heterotopic endometrial glands and stroma in myometrium. It often causes dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, diffusely enlarged uterus, and dyspareunia, as well as infertility [Citation18]. Our study also found that severe endometriosis was quite more common in the AD group, endometriosis and adenomyosis share some common pathophysiological mechanisms, and both may participate in pelvic inflammatory response. Perioperative hyperalgesia of TLH for adenomyosis has several origins, and surgical trauma is likely the most cause. Surgery causes damage to tissue and nerves, and this leads to hyperalgesia via various mechanisms [Citation19,Citation20]. We infer that the pelvic of adenomyosis may suffer from an inflammatory state, and the surgical trauma may cause much more inflammatory factors and cytokines of local ligament cutting edge and systemically spread [Citation21.Citation22]. Adenomyosis with chronic severe dysmenorrhea may also induce the pain hyperalgesia. Yet the exact mechanisms of adenomyosis-induced pain and hyperalgesia are complicated and still unknown. Due to the disease pathogenesis of adenomyosis and clinical manifest, we could understand the postoperative pain of TLH for adenomyosis which is more severe than that of uterine fibroid.

We also found that patients received goserelin (Zoladex 3.6 mg, AstraZeneca, UK) as preoperative treatment before laparoscopic hysterectomy of adenomyosis suffered from less severity of postoperative pain than those without goserelin pretreatment. At present, there are few studies on goserelin in relieving postoperative pain of adenomyosis, and the mechanism of goserelin in relieving postoperative pain is even less known. As we know that GnRH agonist was able to markedly reduce the inflammatory reaction and angiogenesis and to significantly induce apoptosis of ectopic endometrial lesions derived from women with endometriosis and adenomyosis. The levels of serum NPY, PGE2 and NGF at 24h after laparoscopic hysterectomy of adenomyosis reduced with GnRH agonist pretreatment. We speculate that after the preoperative treatment of adenomyosis with goserelin, the systemic and local inflammatory reactions of adenomyosis may be significantly reduced. It may be one of the mechanisms to alleviate the postoperative pain hyperalgesia after TLH for adenomyosis [Citation23].

As we know, it is the first study demonstrates that TLH for adenomyosis suffers from more severe acute postoperative pain and GnRH agonist preoperative treatment could alleviate the postoperative pain intensity. The present study had some limitations. It used data from two academic medical centres only with limited cases. It may require large-sample clinical studies and a long-term follow-up. To identify the result of less severity of postoperative pain after goserelin preoperative treatment, it may require a well-designed randomized clinical trial. Pain after TLH for adenomyosis and hyperalgesia also need further research to uncover the mechanism.

In conclusion, pain after TLH for adenomyosis and uterine fibroid showed considerably different severity, postoperative overall pain and abdominal visceral pains of adenomyosis were more severe compared with uterine fibroid. While patients received goserelin before laparoscopic hysterectomy of adenomyosis suffered from less severity of postoperative total pain than that without goserelin preoperative treatment.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to everyone involved in carrying out the study, analysing the data, and producing the manuscript.

Contribution to authorship

Qing Wu, Yun Zhou and Huafeng Shou conceived the study and participated in its design, drafting and writing the manuscript as well as supervising the study and critically revising the manuscript. Qing Wu, Shanshan Cao and Saijun Sun collected the clinical data. Qing Wu, Yun Zhou, and Hui Li was responsible for drafting and writing the manuscript and statistical analysis. All authors substantially contributed to the revision of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, China. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Availability of data and material

The data of study are not publicly available due to ethical and legal restrictions. However, upon request, data may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Makinen J, Brummer T, Jalkanen J, et al. Ten years of progress–improved hysterectomy outcomes in Finland 1996–2006: a longitudinal observation study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(10):1. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003169.

- Driessen SR, Baden NL, van Zwet EW, et al. Trends in the implementation of advanced minimally invasive gynecologic surgical procedures in The Netherlands. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(4):642–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2015.01.026.

- Walsh CA, Walsh SR, Tang TY, et al. Total abdominal hysterectomy versus total laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease: a meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;144(1):3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.01.003.

- Bijen CBM, Vermeulen KM, Mourits MJE, et al. Costs and effects of abdominal versus laparoscopic hysterectomy: systematic review of controlled trials. PLoS One. 2009;4(10):e7340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007340.

- Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011;152(3 Suppl):S2–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030.

- Alfieri S, Amid PK, Campanelli G, et al. International guidelines for prevention and management of post-operative chronic pain following inguinal hernia surgery. Hernia. 2011;15(3):239–249. doi: 10.1007/s10029-011-0798-9.

- Lirk P, Thiry J, Bonnet MP, PROSPECT Working Group., et al. Pain management after laparoscopic hysterectomy: systematic review of literature and PROSPECT recommendations. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2019;44(4):425–436. Aprdoi: 10.1136/rapm-2018-100024.

- Joo J, Moon HK, Moon YE. Identification of predictors for acute postoperative pain after gynecological laparoscopy (STROBE-compliant article). Medicine (Baltimore). 2019; Oct98(42):e17621. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017621.

- Rawal N. Postoperative pain management in day surgery. Anaesthesia. 1998;53(S2):50–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1998.tb15154.x.

- Kleif J, Kirkegaard A, Vilandt J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of preoperative dexamethasone on postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopy for suspected appendicitis. Br J Surg. 2017;104(4):384–392. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10418.

- Weinbroum AA. Postoperative hyperalgesia-a clinically applicable narrative review. Pharmacol Res. 2017;120:188–205. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.02.012.

- Bautmans I, Njemini R, De Backer J, et al. Surgery induced inflammation in relation to age, muscle endurance, and self-perceived fatigue. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(3):266–273. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp145.

- Hortu I, Turkay U, Terzi H, et al. Impact of bupivacaine injection to trocar sites on postoperative pain following laparoscopic hysterectomy: results from a prospective, multicentre, double-blind randomized controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;252:317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.07.007.

- Turkay Ü, Yavuz A, Hortu İ, et al. The impact of chewing gum on postoperative bowel activity and postoperative pain after total laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;40(5):705–709. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2019.1652891.

- Kehlet H. Procedure-specific postoperative pain management. Anesthesiol Clin North Am. 2005;23(1):203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.atc.2004.11.001.

- Choi JB, Kang K, Song MK, et al. Pain characteristics after total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Int J Med Sci. 2016;13(8):562–568. doi: 10.7150/ijms.15875.

- Brown EN, Pavone KJ, Naranjo M. Multimodal general anesthesia: theory and practice. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(5):1246–1258. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003668.

- Vercellini P, Vigano P, Somigliana E, et al. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(5):261–275. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.255.

- Woolf CJ, Salter MW. Neuronal plasticity: increasing the gain in pain. Science. 2000;288(5472):1765–1769. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1765.

- Wilder-Smith OH, Tassonyi E, Crul BJ, et al. Quantitative sensory testing and human surgery: effects of analgesic management on postoperative neuroplasticity. Anesthesiology. 2003;98(5):1214–1222. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200305000-00025.

- AlAshqar A, Reschke L, Kirschen GW, et al. Role of inflammation in benign gynecologic disorders: from pathogenesis to novel therapies. Biol Reprod. 2021;105(1):7–31. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioab054.

- Liang , Shi S, Duan LY, et al. Celecoxib reduces Inflammation and angiogenesis in mice with adenomyosis. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13(4):2858–2866.

- Khan KN, Kitajima M, Hiraki K, et al. Changes in tissue inflammation, angiogenesis and apoptosis in endometriosis, adenomyosis and uterine myoma after GnRH agonist therapy. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(3):642–653. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep437.