Abstract

Objective: Evaluate the profiles of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) adherence, adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and discontinuation associated with ADRs to provide information for further PEP program improvement and increase adherence to PEP.Methods: The Web of Science, PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library were searched for cohort studies reporting data related to PEP adherence or ADRs (PROSPERO, CRD42022385073). Pooled estimates of adherence, the incidence of ADRs and discontinuation associated with ADRs, and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated separately for the included literature using random effects models. For substantial heterogeneity, meta-regression and subgroup analyses were conducted to explore sources of heterogeneity.Results: Overall adherence was 58.4% (95% CI: 50.9%–65.8%), with subgroup analysis showing differences in adherence across samples, with the highest adherence among men who had sex with men (MSM) (72.4%, 95% CI: 63.4%–81.3%) and the lowest adherence among survivors of sexual assault (SAs) (41.7%, 95% CI: 28.0%–55.3%). The incidence of ADRs was 60.3% (95% CI: 50.3%-70.3%), and the prevalence of PEP discontinuation associated with ADRs was 32.7% (95% CI: 23.7%-41.7%), with subgroup analyses revealing disparities in the prevalence of discontinuation associated with ADRs among samples with different drug regimens. Time trend analysis showed a slight downward trend in the incidence of ADRs and PEP discontinuation associated with ADRs.Conclusion: Adherence to PEP was less than 60% across samples, however, there was significant heterogeneity depending on the samples. SAs had the lowest adherence and the highest incidence of PEP discontinuation. Ongoing adherence education for participants, timely monitoring, and management of ADRs may improve adherence.

KEY MESSAGE

Although PEP has been implemented in most countries for over two decades, there is a notable absence of adherence evaluation and a need for systematic analysis regarding the impact of adverse drug reactions.

We performed a meta-analysis to characterize PEP adherence in samples, assess adverse drug reactions during PEP treatment, and the possibility of PEP discontinuation associated with adverse drug reactions.

Adherence to PEP was less than 60% across samples, however, there was significant heterogeneity depending on the samples. Particularly, survivors of sexual assault have the lowest adherence and the highest incidence of PEP discontinuation.

Adherence, adverse drug reactions, and discontinuation associated with adverse drug reactions of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis: A Meta-analysis based on cohort studies

Introduction

According to statistics from the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) [Citation1], about 38.4 million people were living with HIV globally by the end of 2021, with about 1.5 million new infections and approximately 650,000 deaths. At the same time, the ‘95-95-95’ targets [Citation2] (95% of people living with HIV know their status, 95% of people who know their status are receiving treatment, 95% of people who are receiving treatment are virally suppressed) have been achieved by 85%, 75%, and 68%, respectively. Therefore, it appears that the situation of AIDS prevention and control is still critical, and there remains much to do to eradicate AIDS by 2030. Strengthening joint strategies and adopting more public health strategies are urgently needed to reduce HIV infection and transmission, and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is an essential and economically efficient component of biomedical interventions [Citation3].

The recommended PEP comprises a 28-day course of a combination of two or three antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) within 72 h of HIV exposure for HIV-negative individuals [Citation4,Citation5] to reduce and, if possible, avoid HIV infection. If a significant risk of HIV remains after 28 days, PEP can be transitioned to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Depending on the type of potential exposure, PEP is divided into occupational post-exposure prophylaxis (oPEP) [Citation6] and non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis (NPEP) [Citation7]. PEP was first recommended by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention in 1998 for occupational exposures of healthcare workers (HCWs) [Citation8] to percutaneous injuries (such as needle sticks or sharp cuts), blood, tissue, or other potentially infectious body fluids that come into contact with mucous membranes or incomplete skin (such as chapped, abraded, or exposed skin with dermatitis) [Citation6]. In 2005, the scope of the subject was broadened to encompass non-occupational exposures [Citation9]. This included instances such as sexual assault, human bites that result in skin breakdown, accidental needle sticks that occur outside of work, unsafe sexual practices (such as unprotected sex, multiple sexual partners, anal sex and sex exchanged for drugs or money), and injection drug use [Citation7,Citation9,Citation10].

To achieve effective prevention, adherence is a crucial determinant of PEP [Citation11]. According to the guidance [Citation5], participants who meet the criteria for administration are determined to be in adherence with PEP by taking their medication for the full 28 days as required. Animal models suggest that PEP is most effective when initiated as early as 72 h after exposure and continued for a full 28 days [Citation12,Citation13] and that adherence to antiviral therapy must be at least 95% to ensure a high treatment success rate [Citation14]. However, previously reported adherence was not only low but varied widely among cohorts, with a meta-analysis showing 24% to 78% adherence among participants after non-occupational exposure [Citation15]. Non-adherence seems to be a challenge that requires constant attention, and poor adherence is the result of many barriers [Citation16]. One of the main barriers to good adherence has been identified as being related to patient-specific factors [Citation17], where a variety of factors such as the type of exposure, the complexity of treatment regimens, adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and the relatively low risk of HIV transmission per exposure, may have prevented certain eligible participants from completing the prescribed PEP regimen [Citation18–22]. A study evaluating the implementation of PEP among HCWs in Zimbabwe showed that the uptake of PEP among HCWs was high at 95.9%; unfortunately, adherence to the treatment was only 10.6% and few attended follow-up HIV assessments [Citation23]. In contrast, a study in China showed a high adherence rate of 93.6% among men who have sex with men (MSM) and a follow-up rate of 91.9% [Citation22]. Based on the information available, there seems to be a significant level of inconsistency in adhering to PEP protocols, which has become a pressing issue that needs to be addressed [Citation24].

The effectiveness of PEP is subject to other factors, including drug tolerability and ADRs [Citation25]. Previous studies have demonstrated that over two-thirds of occupational exposers undergoing PEP treatment experience significant ADRs [Citation26]. Results from a large prospective cohort study [Citation27] showed that 96.4% of non-occupationally exposed participants reported at least one ADRs, and 77.1% reported at least one serious adverse reaction. Simultaneously, the data showed that the most common ADRs were fatigue (58.5%), nausea (49.5%), diarrhea (22.5%), and headache (20.7%), with a PEP discontinuation rate of 81.2% associated with ADRs. However, it is worth noting that the ADRs were resolved in nearly all cases once the treatment was stopped. Therefore, with a high incidence of ADRs, participants are likely to interrupt treatment because of ADRs, adherence further deteriorates and PEP discontinuation becomes significant [Citation25]. Since ADRs may differ depending on the particular drug and as ARVs are constantly updated, further research is required in the treatment of PEP to monitor ADRs in all populations, substantial experience will be accumulated to decrease the rate of treatment discontinuation associated with ADRs.

Although PEP has been implemented in most countries for over two decades and is still widely recommended according to current guidelines [Citation27], the challenges of poor adherence and the impact of serious ADRs must be overcome [Citation28]. In 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) formulated updated guidelines on PEP, emphasizing the need to improve PEP adherence. Nonetheless, there is a notable absence of adherence evaluation within samples and a need for systematic analysis regarding the impact of ADRs. Therefore, to better characterize the adherence to PEP, analyze the incidence of ADRs, and provide a reference for further interventions to optimize the delivery of PEP in populations, this study performed a comprehensive meta-analysis of adherence to PEP, the incidence of ADRs, and PEP discontinuation associated with ADRs.

Method

Search strategy

Study selection and data extraction analyses for this study are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [Citation29] guidelines (Supplementary Material 2), and the protocol is pre-registered with Prospero (ID: CRD42022385073). A preliminary search of the Web of Science, PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases was first conducted with the terms HIV and post-exposure prophylaxis from the inception to 24 December 2022. All studies relating to PEP adherence or ADRs were then manually searched separately in these studies, with the search terms shown in Supplementary Material Citation1.

In addition, a manual search of the literature mentioned in the reference list of included studies was performed to obtain relevant studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) prospective or retrospective cohort studies reporting at least one of three data on adherence to PEP, the incidence of ADRs of PEP, and PEP discontinuation rates associated with ADRs; (2) original English-language studies; and (3) adult participant over 18-years-old and considered eligible for PEP initiation, regardless of exposure type and region.

Exclusion criteria: (1) case reports, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or conference abstracts; and (2) studies on the prevention of mother-to-child transmission.

In addition, articles with incomplete information were excluded if data from studies with the same sample were published.

Literature screening, data extraction, and quality assessment

First, databases were searched, all retrieved literature was imported into EndNote X9, and duplicates were removed. Second, two researchers independently screened the titles and abstracts of the articles. After initially eliminating those not meeting the criteria, the qualified literature was read in full to determine the final literature to be included in the study. If there was disagreement it was discussed and resolved with a third researcher.

The following information was extracted independently from all included studies: first author, year of publication, study design, type of exposure and sample characteristics, income level in the study area, drug regimen, the number of people eligible to initiate PEP, the number of people who adhered to prescription medication, the number of participants who recorded whether ADRs occurred, and the number of participants who had discontinuation associated with ADRs. If there were ADRs, each adverse reaction’s type and number of cases were recorded. Participants who completed the entire 28 days of treatment as required were considered to have complied with ‘adherence’.

The quality of each study was assessed according to the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies (Supplementary Materials 1, ) on a rating scale: high quality (scores 7–9), moderate quality (scores 4–6), or low quality (scores 0–3) [Citation30]. Higher scores indicated higher methodological quality and studies were included in the analysis if they had a NOS score of 4 or above. NOS allows for qualitative assessment of cohort studies which has been used in several previous systematic reviews on related topics[Citation31–33] and is therefore applicable to the quality assessment of this study.

Statistical analysis

Heterogeneity among studies was estimated using the Cochran Q and I2 statistics (25%, 50%, and 75% representing low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively) by selecting appropriate effect indicators based on the type of data. Considering the substantial statistical heterogeneity among studies (I2>75%, Q-test p < 0.05), point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the pooled rates of adherence, ADRs, and PEP discontinuation associated with ADRs were calculated separately using a random-effects model, along with the corresponding forest plots. Subgroup analyses and meta-regression analyses were performed with study design type, exposure, samples, and income level (information on income cut-offs according to World Bank standards is provided in Supplementary Material Citation1, SCitation2, http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classification) in the study area, drug regimen, and study quality to identify sources of substantial heterogeneity for each study aim. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Egger’s test together (p > 0.05 indicated no publication bias). Sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding each study consecutively to explore the effect of individual studies on the overall pooled effect size. Data processing and analysis were performed using R (version 4.2.2) and Stata (version 15.1) software.

Results

Literature screening

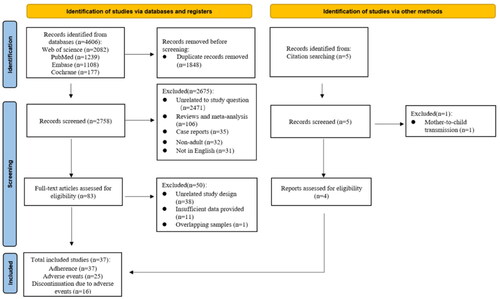

The study selection flow diagram is shown in ; 4606 publications were retrieved from the four databases examined, and after removing duplicate publications and initial screening of titles and abstracts, 83 were read in full for more detailed evaluation, further excluding 38 non-cohort studies, 11 with insufficient data, and one with the same study samples. Five additional studies were identified after a manual search of the literature mentioned in the reference list of the full-texts read, one of which was excluded because it described the prevention of mother-to-child transmission. Ultimately, 37[Citation18–21,Citation27,Citation34–49] articles met all the inclusion criteria for this study.

Research characteristics

The thirty-seven articles included 14 (37.8%) prospective cohort studies and 23 (62.2%) retrospective cohort studies. There were 30 (81.1%) studies on NPEP and seven (18.9%) studies on oPEP, with the highest percentage of MSM (5413, 44.7%), followed by mixed exposure sources (Mixed) (3326, 27.5%), survivors of sexual assault (SAs) (2154, 17.8%), and HCWs (1206, 10.0%). Twenty-six studies were conducted in high-income countries, eight in upper-middle-income countries, and three in lower middle income countries. Of all the 37 included studies, 37 studies reported data on PEP adherence, 25 studies on the incidence of ADRs, and 16 studies on the incidence of PEP discontinuation associated with ADRs. Detailed information is shown in .

Table 1. Basic characteristics and quality evaluation results of the 37 included studies.

Meta-analysis and subgroup analysis of PEP adherence

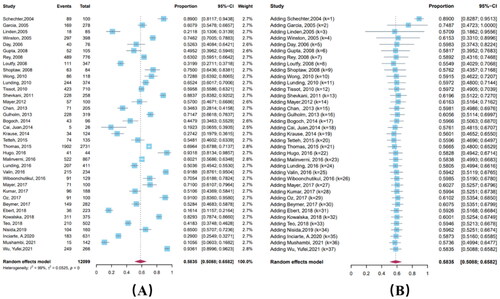

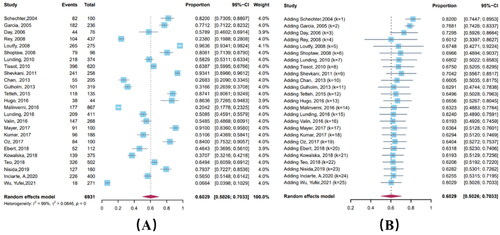

PEP adherence varied widely, ranging from 10.6% to 93.2%, with a pooled estimate of 58.4% (95% CI: 50.9%–65.8%). According to a cumulative meta-analysis including the date of publication, adherence did not exhibit a temporal trend (Coefficient = 0.00043, p = 0.2860); the confidence interval for the combined estimate of adherence gradually narrowed and adherence eventually stabilized at around 60%. The heterogeneity test results showed significant heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 98.8%) ().

Subgroup analysis with variables of study type, exposure, samples, income level, drug regimen, and study quality showed differences in adherence only among samples (p < 0.05) (, Supplementary Materials 1, Table 2), with the highest adherence in MSM (72.4%, 95% CI: 63.4%–81.3%) and the lowest adherence in SAs (41.7%, 95% CI: 28.0%–55.3%).

Table 2. Subgroup and meta-regression analyses of adherence to PEP, ADRs, and discontinuation associated with ADRs.

Meta-analysis and subgroup analysis of ADRs

The results showed a wide variation in the incidence of ADRs, ranging from 6.7% to 96.4%, with a combined estimate of 60.3% (95% CI: 50.3%–70.3%). Cumulative meta-analysis showed a slight downward trend (Coefficient = 0.00850, p < 0.001). The heterogeneity test showed significant heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 99.5%) (). Of the ADRs recorded, nausea was the most frequent, with 36.0% (95% CI: 25.5%-46.4%) of all samples experiencing nausea, followed by fatigue (25.4%, 95% CI: 18.5%–34.8%) and diarrhea (24.2%, 95% CI: 16.8%-31.7%). A forest plot of common ADRs is shown in of Supplementary Material 1.

Subgroup analysis showed differences in the incidence of ADRs by study type and regional income (p < 0.05) (, Supplementary Materials 1, Table 3). The incidence of ADRs was 47.4% (95% CI: 36.7%–58.0%) in retrospective cohort studies and 83.4% (95% CI: 75.2%–91.5%) in prospective cohort studies.

Meta-analysis and subgroup analysis of PEP discontinuation associated with ADRs

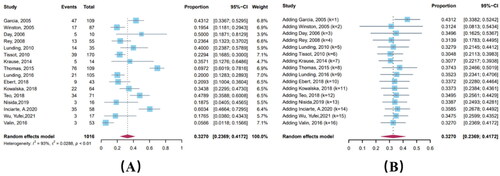

Sixteen articles reported the incidence of PEP discontinuation associated with ADRs to be from 5.7% to 69.7%, with a pooled estimate of 32.7% (95% CI: 23.7%–41.7%). Cumulative meta-analysis showed a mild downward trend (Coefficient = 0.00087, p < 0.001). The heterogeneity test showed significant heterogeneity among the studies included (I2 = 92.7%) ().

Figure 4. Forest plot (A) and cumulative forest plot (B) of PEP discontinuation associated with ADRs.

Subgroup analysis revealed discontinuation rates related to drug regimen only (p < 0.05) (, Supplementary Materials 1, Table 4), with the highest incidence in three-drug regimens (35.4%, 95% CI: 24.0%–47.7%). Concerning samples, SAs had the highest incidence at 36.4% (95% CI: 20.7%–52.1%), followed by MSM (33.1%, 95% CI: 13.0%–53.1%).

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Plotting the funnel plots for each study purpose showed fair symmetry (), and Egger’s test revealed no significant publication bias (p > 0.05). The results of the sensitivity analyses and forest plots () showed that none of the 95% CI combined effect sizes fluctuated by more than 3.0% after excluding the individual studies with the greatest effect on heterogeneity, which was not significantly different, suggesting that the results were relatively stable.

Discussion

This study revealed that the overall adherence was 58.4%, and there was no statistically significant difference in adherence between NPEP and oPEP, treatment adherence remains a challenge in PEP management. The incidence of ADRs was 60.3%, and the incidence of PEP discontinuation associated with ADRs was 32.7%, ADRs may have an impact on adherence, and more research is required to examine the possibility of improving adherence to assist high-risk groups.

A meta-analysis published in 2014 showed an overall adherence rate of only 56.6%, and adherence to the 28-day regimen continues to be a challenge across populations and exposure types [Citation50]. Nearly 10 years after that study, guidelines on PEP have continued to be updated and medication regimens have changed. However, our findings showed an overall adherence rate of 58.4% by the end of 2022, an increase of only 1.8%. Moreover, the indication of PEP after sexual exposure has been recommended by various international guidelines, but time trend analyses show no time trend in adherence, which has stabilized below 60% in recent years. This may indicate that, despite continued updating of PEP guidelines or HIV treatment guidelines on PEP in recent years [Citation6], adherence has not trended upwards over time and remains generally low and suboptimal, which may be related to individual risk reassessment and ADRs. Recommendations for PEP should be considered in conjunction with existing WHO guidelines for improving adherence to PEP.

Although studies have demonstrated high rates of PEP acceptance and utilization [Citation3,Citation38,Citation51,Citation52], and most individuals are willing to seek PEP after high-risk exposures, some participants discontinue medication after risk reassessment [Citation11] because continued treatment is not needed, others are unable or unwilling to adhere to drug regimens for pharmacologic reasons, including pill burden, anxiety about ADRs, and poor tolerability of specific regimens that prevent participants from adhering to drug regimens [Citation53]. Previous studies have shown that ADRs are a predictor variable for nonadherence to PEP [Citation54], and in an analysis to determine the association between ADRs and adherence [Citation48], participants who never reported ADRs had 57% higher adherence compared with those who reported at least one adverse drug reaction, and all participants who discontinued treatment cited severe ADRs as the primary reason for non-adherence. Also, a study conducted at Fenway Health Centre to assess medication dose adherence showed poor adherence to twice-daily dosing probably because some participants would forget the second dose, while adherence to the once-daily regimen was excellent. Therefore, if the mode of administration cannot be changed, clinicians can emphasize the importance of the second daily drug dose to improve compliance with the second dose when prescribing PEP. Low adherence will reduce the effectiveness of PEP [Citation55], and in the future, it will be important to focus on modifying PEP regimens by reducing ADRs and choosing the right number of drugs to prescribe wherever possible, along with increased counselling at the earliest opportunity, in order to improve adherence.

Subgroup analyses showed significant differences in adherence among samples, with SAs being the lowest, consistent with previous studies. A meta-analysis of SAs showed poor adherence in all settings, with an overall adherence rate of 40% [Citation55], much lower than that of non-forcibly exposed HIV patients (78%) [Citation56], which may be related to the characteristics of these specific samples. One potential explanation is the inadequacy of comprehensive post-sexual assault care services. Most victims who experience severe emotional distress have difficulty deciding whether to receive PEP after sexual assault in the context of the social stigma and stigmatization associated with sexual violence [Citation27,Citation34], resulting in low uptake rates [Citation57,Citation58]. The post-traumatic stress response suffered by SAs may make it difficult for them to take daily pills that remind them of the incident [Citation59]. In addition, the cost-effectiveness and ADRs associated with PEP medications prevent most victims from completing the medication program. Krause et al. evaluated the current status of SAs adherence in the emergency department and found that only 27.4% of participants adhered; to improve adherence, this emergency department changed the drug regimen that was associated with too many ADRs, resulting in a reduction in discontinuation rates among SAs [Citation47]. Our study also discovered a higher incidence of ADRs in SAs and the highest incidence of PEP discontinuation associated with ADRs, potentially contributing to the low adherence in these samples. Studies have demonstrated that SAs was a risk factor for decreased adherence [Citation60]; consequently, tailored interventions must be implemented to increase adherence. An intervention study incorporating a nurse-driven model of sexual assault care into existing hospital services found that adherence among SAs increased from 20% to 58% after introducing interventions such as sexual assault counselling and management [Citation61]. Michelle et al. also indicated that offering active follow-up resulted in adherence among SAs of up to 74% [Citation62]. At the same time, the drug regimen was optimized to provide routine symptomatic treatment for possible ADRs. Qualitative studies [Citation63] have shown that adding antiemetic and analgesic medications to the prescription 14 days before treatment may reduced the impact of ADRs, enhanced the emotional and psychosocial state of participants, and may have increased the likelihood of SAs medication adherence. In addition, in response to the epidemiological characteristics of SAs, action is required to implement appropriate interventions such as family support and psychosocial support through community home-care programs, peer counselling, training of medical staff, and selection of safer drug regimens to improve adherence.

Simultaneously, subgroup analysis revealed that MSM had a high likelihood of PEP discontinuation, even with the highest adherence, just below SAs. The high level of treatment adherence was possibly due to the strong desire of MSM, as a high-risk group, to avoid the stigma associated with being HIV-positive, and the inclusion of more young participants in the study, most of whom were highly educated and able to understand the significance of treatment adherence. Despite the highest adherence among MSM, close to 30% of participants still fail to adhere, and as a vulnerable and stigmatized group, prevention and mobilization strategies need to be rolled out for the sake of the MSM HIV epidemic, with an emphasis on continuing to invest in better ways of collecting data on adherence and refining existing adherence measures to accurately measure adherence.

A recent meta-analysis based on global data [Citation32] showed that, despite high adherence in MSM, a proportion of participants discontinued NPEP after experiencing ADRs, and ADRs were the most prevalent reason for premature discontinuation. Multivariate modelling analysis further highlighted ADRs as an important factor influencing PEP discontinuation [Citation22]. Participants may experience persistent vomiting after taking medication, thereby reducing the effectiveness of other medications in the regimen. In addition, lack of private health insurance was associated with short-term discontinuation for gastrointestinal ADRs, and lower health insurance coverage for MSM [Citation64] resulted in less access to ongoing medical care and more difficulty in obtaining medications to treat ADRs, leading to higher discontinuation rates. However, in a retrospective cohort from Brazil [Citation18], despite an 82% incidence of ADRs, 89.0% of MSM completed the full 28-day PEP regimen, and discontinuation associated with ADRs was rare owing to the provision of professional counselling regarding ADRs. Ondansetron (Zofran) has been proven to be a very effective agent in the treatment of highly and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy and radiotherapy in adults and children [Citation65]. A retrospective study supported the efficacy of this class of antiemetic medication in alleviating nausea and/or vomiting induced by drugs in MSM, showing demonstrable improvement in all patients after taking ondansetron [Citation66]. Therefore, continuous adherence education and medication guidance are essential to improve compliance among MSM during treatment, the most important aspect of which is to provide symptomatic treatment such as antiemetics and antidiarrheals with the PEP initiation kit to minimize the impact of ADRs and maximize the preventive effect of PEP as much as possible [Citation67]. Meanwhile, studies have shown that MSM still have high rates of HIV infection after completing PEP [Citation68], so if high risk behaviors are frequent and PEP blockers are taken regularly, ideally it may be prudent to wait 4 weeks or more and monitor PEP users for acute HIV infection and then implement PrEP as necessary [Citation69]. It is therefore important to carry out risk consultations after the PEP has been completed to discuss the available interventions in combination with chemoprophylaxis, and PrEP and PEP services should be combined where appropriate.

All antiretroviral drugs can cause ADRs [Citation70], so the frequency, severity, duration, and reversibility of ADRs are important considerations in the development of prophylactic treatment regimens. A randomized clinical trial evaluating drug regimens for ADRs in PEP found a 73.4% incidence of ADRs [Citation71], which may be attributable to substantial drug interactions between antiretroviral medications. Some drug interactions are of substantial therapeutic benefit, while others may increase the potential for ADRs, such as the cumulative effects of concomitant use of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors or concomitant use of protease inhibitors [Citation26]. The study showed that participants in Barcelona had significantly fewer ADRs after professional drug counselling and risk assessment [Citation71]. Also, subgroup analysis revealed differences in the incidence of ADRs across study design types, with retrospective cohort studies having a significantly lower incidence of ADRs than prospective cohort studies. A possible reason for this was that most data from retrospective studies were collected retrospectively from medical records, and the propensity of participants to report ADRs passively was generally low [Citation48], combined with the fact that there were many types of ADRs and participants may be confused or forgetful, resulting in missing data and causing differences between the two study design types when interpreting the results. All antiretroviral medications should be administered in close consultation with a physician or clinical pharmacist to reduce the incidence of ADRs. In addition, a professional trained to meticulously record ADRs and provide timely guidance needs to be consulted at every visit.

Previous studies [Citation43] have shown that intolerance to ADRs was the primary cause of non-adherence to PEP. Gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea and vomiting are prevalent ADRs strongly associated with treatment discontinuation [Citation35,Citation36]. Participants who experienced vomiting were less likely to complete PEP than those who did not, possibly because persistent vomiting negatively impacted their quality of life more than other ADRs, resulting in early discontinuation and reduced treatment adherence, thereby affecting clinical outcomes. In addition, the results of subgroup analyses also showed differences in discontinuation rates across dosing regimens, with triple therapy having the highest discontinuation rates, which may be related to drug selection. Decision models from one study suggested that three-drug regimens were less well tolerated than two-drug regimens, and that treatment regimens were often incomplete, making some participants choose to discontinue, leading to increased cases of HIV transmission after high-risk exposure [Citation72]. However, as the efficacy of three-drug regimens increases, some studies have pointed out that a PEP regimen with two drugs was effective, but it was better to use three drugs and therefore favored using the three-drug regimens. After 2014, WHO recommended guidelines gradually moved toward prioritizing the novel three-drug regimen tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) + lamivudine (3TC) or emtricitabine (FTC), considering better safety and lower costs. Studies have demonstrated that the incidence of discontinuation associated with ADRs was significantly lower with TDF/FTC-LPV/r tablets than with other dosing regimens [Citation25]. In 2021, the WHO updated the medication guidelines [Citation73], and emphasized that TDF + 3TC + Dolutegravir (DTG) has become the preferred regimen for PEP throughout the world because of its rapid onset and fewer ADRs. Meanwhile, the updated guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV suggest that newer antiretroviral regimens have fewer serious and intolerable ADRs than those used in the past. The results of the time trend analysis of this study showed a slight downward trend in the incidence of ADRs and discontinuation associated with ADRs, which may be related to the gradual change of drug regimens to those with better tolerability and lower discontinuation rates. By developing drugs with a higher safety profile, the incidence of adverse reactions in participants may be reduced or even completely tolerated, and discontinuation of medication due to adverse reactions may also be reduced to some extent, and adherence may be improved as a result. However, it is still necessary to conduct effective counselling and education and monitor participants for treatable ADRs through active follow-up to improve medication adherence.

This research had several limitations. First, the studies were highly heterogeneous, with subgroup and meta-regression analyses explaining only a portion of the heterogeneity, so caution is required when interpreting the pooled estimates. Second, PEP has not yet become routine practice in many low and middle-income nations, and there are relatively few relevant studies. Therefore, the validity of the subgroup analyses may be compromised by the limited quantity of literature included. Third, the results of this study may not be generalizable to all populations because male SAs were not included (owing to the small numbers) and they tended to have higher risk exposures. Also, mixed samples were not specifically grouped due to unclear data, but they may involve participants that we used for subgroup analyses.

Conclusion

To summarize, adherence to PEP was less than 60% across samples, and ADRs may have had an impact on adherence. Given that SAs had the lowest adherence and the highest incidence of discontinuation associated with ADRs, it makes sense to improve a package of standardized care services following sexual assault and to consider systems to manage treatable ADRs. As a long-term intervention, scientific public health policies, close monitoring and timely management of ADRs, and education, assessment, and training of participants on medication adherence are needed to gradually improve adherence to PEP in all populations.

Authors’ contributions

All authors agree to take responsibility for all aspects of the work. Study design: SSL and BW; Literature search, information extraction, quality evaluation, and data analysis: SSL, DFY, and YZ; Drafting the manuscript: SSL; Critical revision and assessment: SSL, DFY, YZ, GFF, and BW.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (3.5 MB)Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the cooperation of all participants in the relevant studies, as well as the researchers who provided the data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in this article and its Supplementary Materials.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Global HIV & AIDS statistics.—2022 fact sheet | UNAIDS, https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet. Accessed 12 March 2023.

- Pai NP, Karellis A, Kim J, et al. Modern diagnostic technologies for HIV. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(8):1–13. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30190-9.

- Logie CH, Wang Y, Lalor P, et al. Pre and post-exposure prophylaxis awareness and acceptability among sex workers in Jamaica: a cross-sectional study. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(2):330–343. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02972-5.

- Heendeniya A, Bogoch II. Antiretroviral medications for the prevention of HIV infection: a clinical approach to preexposure prophylaxis, postexposure prophylaxis, and treatment as prevention. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33(3):629–646. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2019.04.002.

- Guidelines on post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV and the use of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis for HIV-related infections among adults, adolescents and children: recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014 (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/145719., accessed 1 June 2023).

- Kuhar DT, Henderson DK, Struble KA, et al. Updated US public health service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency virus and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(9):875–892. doi: 10.1086/672271.

- Announcement: updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(17):458.

- Public health service guidelines for the management of health-care worker exposures to HIV and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. Centers for disease control and prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47(Rr-7):1–33.

- Smith DK, Grohskopf LA, Black RJ, et al. Antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV in the United States: recommendations from the U.S. Department of health and human services. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(Rr-2):1–20.

- Shipeolu L, Sampsel K, Reeves A, et al. HIV nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis for sexual assault cases: a 3-year investigation. AIDS. 2020;34(6):869–876. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002507.

- Sultan B, Benn P, Waters L. Current perspectives in HIV post-exposure prophylaxis. HIV AIDS. 2014;6:147–158. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S46585.

- Tsai CC, Emau P, Follis KE, et al. Effectiveness of postinoculation (R)-9-(2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl) adenine treatment for prevention of persistent simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmne infection depends critically on timing of initiation and duration of treatment. J Virol. 1998;72(5):4265–4273. doi: 10.1128/JVI.72.5.4265-4273.1998.

- Roland ME, Neilands TB, Krone MR, et al. Seroconversion following nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis against HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(10):1507–1513. doi: 10.1086/497268.

- Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004.

- Bryant J, Baxter L, Hird S. Non-occupational postexposure prophylaxis for HIV: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(14):iii, ix-x, :1–60. doi: 10.3310/hta13140.

- Devine F, Edwards T, Feldman SR. Barriers to treatment: describing them from a different perspective. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:129–133. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S147420.

- Kvarnström K, Airaksinen M, Liira H. Barriers and facilitators to medication adherence: a qualitative study with general practitioners. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e015332. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015332.

- Schechter M, do Lago RF, Mendelsohn AB, et al. Behavioral impact, acceptability, and HIV incidence among homosexual men with access to postexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(5):519–525. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00010.

- Garcia MT, Figueiredo RM, Moretti ML, et al. Postexposure prophylaxis after sexual assaults: a prospective cohort study. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(4):214–219. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000149785.48574.3e.

- Gupta A, Anand S, Sastry J, et al. High risk for occupational exposure to HIV and utilization of post-exposure prophylaxis in a teaching hospital in pune, India. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:142. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-142.

- Rey D, Bendiane MK, Bouhnik A-D, et al. Physicians’ and patients’ adherence to antiretroviral prophylaxis after sexual exposure to HIV: results from South-Eastern France. Aids Care. 2008;20(5):537–541. doi: 10.1080/09540120701867198.

- Wu Y, Zhu Q, Zhou Y, et al. Implementation of HIV non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men in 2 cities of Southwestern China Medicine. 2021;100(43):e27563. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000027563.

- Mushambi F, Timire C, Harries AD, et al. High post-exposure prophylaxis uptake but low completion rates and HIV testing follow-up in health workers, Harare, Zimbabwe. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2021;15(4):559–565. doi: 10.3855/jidc.12214.

- Gantner P, Hessamfar M, Souala MF, et al. Elvitegravir-cobicistat-emtricitabine-tenofovir alafenamide single-tablet regimen for human immunodeficiency virus postexposure prophylaxis. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(5):943–946.

- Tosini W, Muller P, Prazuck T, et al. Tolerability of HIV postexposure prophylaxis with tenofovir/emtricitabine and lopinavir/ritonavir tablet formulation. AIDS. 2010;24(15):2375–2380. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833dfad1.

- Lee LM, Henderson DK. Tolerability of postexposure antiretroviral prophylaxis for occupational exposures to HIV. Drug Saf. 2001;24(8):587–597. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200124080-00003.

- Loutfy MR, Macdonald S, Myhr T, et al. Prospective cohort study of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis for sexual assault survivors. Antivir Ther. 2008;13(1):87–95. doi: 10.1177/135965350801300109.

- Nie J, Sun F, He X, et al. Tolerability and adherence of antiretroviral regimens containing Long-Acting fusion inhibitor albuvirtide for HIV post-exposure prophylaxis: a cohort study in China Infect Dis Ther. 2021;10(4):2611–2623. doi: 10.1007/s40121-021-00540-5.

- Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647.

- Wells G, Shea BO, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle‑Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta‑Analyses. Ottawa, ON: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2000. Available from: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 15 February 2023.

- Bispo S, Chikhungu L, Rollins N, et al. Postnatal HIV transmission in breastfed infants of HIV-infected women on ART: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21251. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21251.

- Wang Z, Yuan T, Fan S, et al. HIV nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of global data. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2020;34(5):193–204. doi: 10.1089/apc.2019.0313.

- Lemma T, Silesh M, Taye BT, et al. HIV serostatus disclosure and its predictors among children living with HIV in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;10:859469. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.859469.

- Linden JA, Oldeg P, Mehta SD, et al. HIV postexposure prophylaxis in sexual assault: current practice and patient adherence to treatment recommendations in a large urban teaching hospital. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(7):640–646. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.01.015.

- Winston A, McAllister J, Amin J, et al. The use of a triple nucleoside-nucleotide regimen for nonoccupational HIV post-exposure prophylaxis. HIV Med. 2005;6(3):191–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00288.x.

- Day S, Mears A, Bond K, et al. Post-exposure HIV prophylaxis following sexual exposure: a retrospective audit against recent draft BASHH guidance. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(3):236–237. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.017764.

- Shoptaw S, Rotheram-Fuller E, Landovitz RJ, et al. Non-occupational post exposure prophylaxis as a biobehavioral HIV-prevention intervention. Aids Care 2008;20(3):376–381. doi: 10.1080/09540120701660353.

- Lunding S, Katzenstein TL, Kronborg G, et al. The Danish PEP registry: experience with the use of postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) following sexual exposure to HIV from 1998 to 2006. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(1):49–52. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181b6f284.

- Tissot F, Erard V, Dang T, et al. Nonoccupational HIV post-exposure prophylaxis: a 10-year retrospective analysis. HIV Med. 2010;11(9):584–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00826.x.

- Wong K, Hughes CA, Plitt S, et al. HIV non-occupational postexposure prophylaxis in a Canadian province: treatment completion and follow-up testing. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21(9):617–621. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008482.

- Shevkani M, Kavina B, Kumar P, et al. An overview of post exposure prophylaxis for HIV in health care personals: Gujarat scenario. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2011;32(1):9–13. doi: 10.4103/0253-7184.81247.

- Mayer KH, Mimiaga MJ, Gelman M, et al. Raltegravir, tenofovir DF, and emtricitabine for postexposure prophylaxis to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV: safety, tolerability, and adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(4):354–359. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824a03b8.

- Chan ACH, Gough K, Yoong D, et al. Non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV at St michael’s hospital, toronto: a retrospective review of patient eligibility and clinical outcomes. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24(5):393–397. doi: 10.1177/0956462412472826.

- Gulholm T, Jamani S, Poynten IM, et al. Non-occupational HIV post-exposure prophylaxis at a Sydney metropolitan sexual health clinic. Sex Health. 2013;10(5):438–441. doi: 10.1071/SH13018.

- Bogoch II, Scully EP, Zachary KC, et al. Patient attrition between the emergency department and clinic among individuals presenting for HIV nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(11):1618–1624. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu118.

- Cai J, Xiao J, Zhang Q. Side effects and tolerability of post-exposure prophylaxis with zidovudine, lamivudine, and lopinavir/ritonavir: a comparative study with HIV/AIDS patients. Chin Med. 2014;127(14):2632–2636.

- Krause KH, Lewis-O’Connor A, Berger A, et al. Current practice of HIV postexposure prophylaxis treatment for sexual assault patients in an emergency department. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24(4):E407–e412. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.04.003.

- Tetteh RA, Nartey ET, Lartey M, et al. Adverse events and adherence to HIV post-exposure prophylaxis: a cohort study at the Korle-Bu teaching hospital in accra, Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):573. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1928-6.

- Thomas R, Galanakis C, Vézina S, et al. Adherence to post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and incidence of HIV seroconversion in a major North American cohort. PLOS One. 2015;10(11):e0142534. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142534.

- Ford N, Irvine C, Shubber Z, et al. Adherence to HIV postexposure prophylaxis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2014;28(18):2721–2727. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000505.

- Fusca L, Hull M, Ross P, et al. High interest in syphilis pre-exposure and post-exposure prophylaxis among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in vancouver and toronto. Sex Transm Dis. 2020;47(4):224–231. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001130.

- Zhou L, Assanangkornchai S, Shi Z, et al. Acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis and non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in guilin. China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3579. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063579.

- Parkin JM, Murphy M, Anderson J, et al. Tolerability and side-effects of post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection. Lancet. 2000;355(9205):722–723. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)05005-9.

- Neu N, Heffernan-Vacca S, Millery M, et al. Postexposure prophylaxis for HIV in children and adolescents after sexual assault: a prospective observational study in an urban medical center. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(2):65–68. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000225329.07765.d8.

- Chacko L, Ford N, Sbaiti M, et al. Adherence to HIV post-exposure prophylaxis in victims of sexual assault: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(5):335–341. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050371.

- Oldenburg CE, Bärnighausen T, Harling G, et al. Adherence to post-exposure prophylaxis for non-forcible sexual exposure to HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(2):217–225. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0567-0.

- Muriuki EM, Kimani J, Machuki Z, et al. Sexual assault and HIV postexposure prophylaxis at an urban african hospital. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2017;31(6):255–260. doi: 10.1089/apc.2016.0274.

- Inciarte A, Leal L, Masfarre L, et al. Post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection in sexual assault victims. HIV Med. 2020;21(1):43–52. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12797.

- Krakower DS, Jain S, Mayer KH. Antiretrovirals for primary HIV prevention: the current status of pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12(1):127–138. doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0253-5.

- Malinverni S, Gennotte AF, Schuster M, et al. Adherence to HIV post-exposure prophylaxis: a multivariate regression analysis of a 5 years prospective cohort. J Infect. 2018;76(1):78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.10.008.

- Kim JC, Askew I, Muvhango L, et al. Comprehensive care and HIV prophylaxis after sexual assault in rural South Africa: the refentse intervention study. BMJ. 2009;338(1):b515–b515. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b515.

- Roland ME. A model for communitywide delivery of postexposure prophylaxis after potential sexual exposure to HIV. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(5):294–296. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000258321.62272.0e.

- Arend E, Maw A, de Swardt C, et al. South African sexual assault survivors’ experiences of post-exposure prophylaxis and individualized nursing care: a qualitative study. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013;24(2):154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.02.007.

- Cooley LA, Hoots B, Wejnert C, et al. Policy changes and improvements in health insurance coverage among MSM: 20 U.S. Cities, 2008-2014. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(3):615–618. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1567-7.

- Stiakaki E, Savvas S, Lydaki E, et al. Ondansetron and tropisetron in the control of nausea and vomiting in children receiving combined cancer chemotherapy. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1999;16(2):101–108.

- Currow DC, Coughlan M, Fardell B, et al. Use of ondansetron in palliative medicine. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(5):302–307. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(97)00079-1.

- Lu TY, Mao X, Peng EL, et al. [Bibliometric analysis on research hotspots on HIV post-exposure prophylaxis related articles in the world, 2000–2017]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2018;39(11):1501–1506.

- Zablotska IB, Prestage G, Holt M, et al. Australian gay men who have taken nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis for HIV are in need of effective HIV prevention methods. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58(4):424–428. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318230e885.

- Jain S, Krakower DS, Mayer KH. The transition from postexposure prophylaxis to preexposure prophylaxis: an emerging opportunity for biobehavioral HIV prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60 S(Suppl 3):S200–S4. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ094.

- Benn PD, Mercey DE, Brink N, et al. Prophylaxis with a nevirapine-containing triple regimen after exposure to HIV-1. Lancet. 2001;357(9257):687–688. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04139-8.

- Leal L, León A, Torres B, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing ritonavir-boosted lopinavir versus raltegravir each with tenofovir plus emtricitabine for post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(7):1987–1993. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw049.

- Bassett IV, Freedberg KA, Walensky RP. Two drugs or three? Balancing efficacy, toxicity, and resistance in postexposure prophylaxis for occupational exposure to HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(3):395–401. doi: 10.1086/422459.

- Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, testing, treatment, service delivery and monitoring: recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240031593., accessed 1 June 2023).