Abstract

Aim: Groove pancreatitis (GP) is a rare type of chronic pancreatitis characterized by varying degrees of thickening and scarring of the duodenal wall, duodenal lumen stenosis, mucosal hypertrophy with plicae and cyst formation. GP is primarily observed in middle-aged male patients with a history of alcohol consumption. Clinical symptoms are usually non-specific, and there is currently no unified diagnostic standard. However, imaging methods, particularly endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), are useful for diagnosis. EUS-guided biopsy can provide a strong basis for the final diagnosis. This review summarizes the value of EUS and its derivative technologies in the diagnosis, differential diagnosis and treatment of GP.

Methods: After searching in PubMed and Web of Science databases using ‘groove pancreatitis (GP)’ and ‘endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)’ as keywords, studies related were compiled and examined.

Results: EUS and its derivative technologies are of great significance in the diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and treatment of GP, but there are still limitations that need to be comprehensively applied with other diagnostic methods to obtain the most accurate results.

Conclusion: EUS has unique value in both the diagnosis and treatment of GP. Clinicians need to be well-versed in the advantages and limitations of EUS for GP diagnosis to select the most suitable imaging diagnostic method for different cases and to reduce the unnecessary waste of medical resources.

1. Introduction

Groove pancreatitis (GP), also known as duodenal dystrophy, paraduodenal pancreatitis, cystic dystrophy of heterotopic pancreas, paraduodenal wall cyst, pancreatic hamartoma of the duodenum and myoadenomatosis, is a type of pancreatitis that affects the space comprising the pancreatic head, duodenum and common bile duct [Citation1]. The specific cause of this disease is not clear; however, it may be related to long-term alcoholism, smoking, peptic ulcer, ectopic pancreas, gastrectomy, biliary diseases and anatomical or functional disorders of the minor duodenal papilla [Citation2]. There are three types of GP: the pure form, which is limited to the groove area without the pancreatic head, the pancreatic parenchyma and the main pancreatic duct. The segmental form extends beyond the above areas, forms fibrous scars and wraps around the pancreatic head and main pancreatic duct, causing stenosis and dilation. The diffuse form involves the entire pancreas and presents as chronic pancreatitis [Citation3].

Patients with GP present with atypical clinical symptoms including epigastric pain, weight loss and vomiting due to duodenal obstruction. Laboratory examinations also lack specificity; carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen (CA) 199 levels in GP patients are generally normal, although some patients may have slight increases in pancreatic amylase, lipase, pancreatic elastase, glutamyltransferase and alkaline phosphatase levels. Atypical clinical symptoms and laboratory examinations result in the diagnosis of GP, which mainly relies on imaging examinations.

Conventional diagnostic methods for GP include computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Currently, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has become the preferred examination for diagnosis and treatment of GP. In addition to accurately displaying the anatomical structure of the groove area, EUS can perform punctures and biopsies to distinguish GP from pancreatic cancer, guide the next step of treatment and avoid unnecessary surgery [Citation3]. This article reviews the diagnostic and therapeutic value of EUS for GP.

2. Common imaging features of GP

2.1. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) barium swallow test and gastroscopy

Some patients who undergo the GI barium swallow test show stenosis of the gastric antrum and duodenum, whereas gastroscopy shows congestion, erosion, edema, stenosis and polypoid hyperplasia in the descending part of the duodenum. However, some patients still have intact mucosa, and a biopsy under gastroscopy cannot always provide a representative tissue specimen [Citation4].

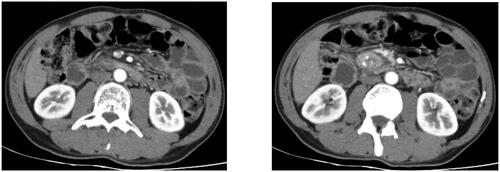

2.2. CT

Typical CT manifestations of GP include thickening of the medial wall of the duodenum, unclear fat accumulation, obvious soft tissue in the groove area and a cyst in the duodenal wall. Chronic GP may also manifest as calcification of the pancreatic parenchyma, and dilation and tortuosity of the pancreatic duct (). In the segmental form, CT can detect lump-like enlargements of the pancreatic head, making it difficult to distinguish GP from pancreatic head cancer [Citation5–7].

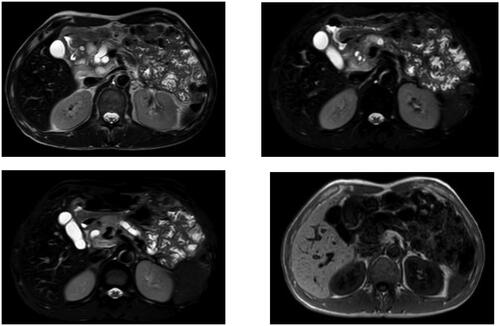

2.3. MRI

The most typical MRI manifestation of GP is a patchy mass between the head of the pancreas and the C-ring of the duodenum. The mass appears as a low signal on T1-weighted images, and can appear as a low, equal or slightly high signal on T2-weighted images. Changes in the T2 signal depend on histological changes in the lesion area; subacute diseases display brighter T2 images due to edema, whereas chronic diseases have lower signals due to fibrosis (). MRCP can provide information about the pancreatic and bile ducts, and GP can be characterized by gradual thinning of the distal common bile duct, which helps distinguish GP from distal cholangiocarcinoma. Contrast-enhanced dynamic MRI images of chronic GP can show delayed and progressive inhomogeneous enhancement. In addition, most pancreatic cancer masses also have dense fibrous tissue, which makes it difficult to differentiate between the two diseases by MRI [Citation8].

3. Diagnostic value of EUS and its derivative technologies for GP

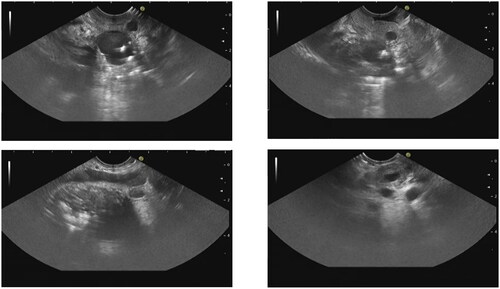

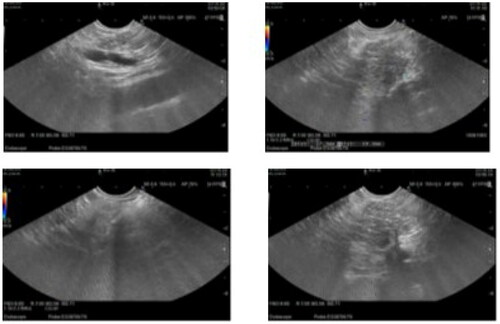

Currently, CT is considered the first-line imaging method in most treatment centers, allowing doctors to diagnose GP and differentiate it from pancreatic tumors in most cases. Because of its high tissue contrast resolution, MRI is the imaging method of choice when CT results are uncertain. EUS can more accurately detect changes in the duodenal wall compared to CT and MRI, and provides the possibility of obtaining cytohistological samples. Therefore, EUS must be considered as a problem-solving method in difficult cases ( and ).

Table 1. Different imaging and endoscopic features of suspected cases of GP with other causes cannot be ruled out.

Table 2. EUS performance of GP patients.

3.1. EUS

EUS has the ability to provide the precise localization, scope and characteristics of submucosal tumors, enabling differentiation of the causes of stenosis (such as tumors and annular pancreas). The typical EUS manifestations of GP include thickening of the duodenal wall, duodenal stenosis and hypoechoic structures in the submucosa and intrinsic muscularis of the duodenal wall, that is, cysts of the duodenal wall with or without common bile duct stenosis and a pancreatic head mass. Pancreases presenting with chronic pancreatitis typically appear atrophic with heterogeneous lobular parenchyma ( and ). Matteo et al. showed that, for cases of duodenal wall thickening, the detection rates of EUS, MRI and CT were 96.5%, 91.0% and 84.1%, respectively, and those of duodenal wall cysts were 94.4%, 81.9% and 75.7%, respectively [Citation14]. Okasha et al. also concluded that in 21 patients suspected of GP who underwent CT, MRI and EUS examinations simultaneously, 9 (42.8%), 5 (23.8%) and 16 (76.2%) showed thickening of the duodenal wall, with 10 (47.6%), 8 (38%) and 12 (57%) detected pancreatic head enlargement/mass, 5 (23.8%), 1 (4.8%) and 11 (52.4%) detected duodenal wall cyst [Citation3]. Although there are few literature comparing EUS with other imaging methods, the conclusions drawn from current literature suggest that EUS is more accurate in diagnosing duodenal wall changes in GP than MRI and CT. Due to the clinical manifestation of duodenal stenosis in this disease, conventional probes may have diagnostic problems, 20 MHz mini probe sonography provides more information in cases of intracavitary stenosis, making the diagnosis more accurate [Citation15].

3.2. EUS elastography (EUS-E) and contrast-enhanced EUS (CE-EUS)

Currently, there are relatively few studies on the application of EUS-E and CE-EUS in GP diagnosis. Surinder et al. showed that the duodenal wall was thickened due to fibrosis and appeared hard on EUS-E. The cystic area showed no enhancement owing to the absence of any contrast agent on CE-EUS. Owing to fibrosis, the surrounding thickened walls have a limited distribution of blood vessels and exhibit patchy delayed enhancement. This ensures ease of distinguishing GP from malignant tumors; most tumors have vascular hyperplasia, and in contrast with the patchy enhancement of GP, hyperenhancement is observed on CE-EUS [Citation16].

3.3. EUS-fine needle aspiration (FNA)/fine needle biopsy (FNB)

Because of the presence of pancreatic head masses and enlarged lymph nodes around the pancreatic head in some cases of GP, it needs to be accurately distinguishable from malignant tumors. EUS-FNA can collect samples from suspected lesions, making it an ideal method for performing this distinction. Approximately 90% of cases can be diagnosed using puncture cytology [Citation17]. Jun et al. [Citation18] conducted an EUS-FNA examination in 23 patients (10 with groove cancer (GC) and 13 with GP) and found that the diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy of EUS-FNA were 90%, 100%, 100%, 92.86% and 95.65%, respectively. This study shows that the diagnostic accuracy of FNA for GP is relatively satisfactory. In highly suspected cases of GP, EUS-FNA was performed on the abnormally thickened duodenal wall and groove area, revealing only inflammatory changes and no malignant or poorly developed cells; this largely ruled out the possibility of malignant tumors [Citation9, Citation13]. For patients with imaging findings highly suggestive of GP and clinical suspicion of malignant tumors, EUS-FNA examination before formulating treatment plans usually provides satisfactory results [Citation10].

However, EUS-FNA biopsy results show significant differences, mainly depending on the sampling location. Cytological features related to reactive cell abnormalities caused by pancreatitis may mimic those of malignant tumors. At the same time, FNA has potential limitations in cytology, including the inability to determine tissue structure and the limited number of quantitative samples for further immunohistochemical staining. In most patients, the sample size obtained through FNB overcomes the limitation of insufficient sample size obtained through FNA. Therefore, the histology of FNB is considered the best method for distinguishing between benign and malignant pancreatic lesions. To date, no study has compared the diagnostic efficacies of EUS-FNA and FNB for GP. However, Wong et al. [Citation19] analyzed the diagnostic performances of EUS-FNA and FNB in solid pancreatic masses and concluded that the diagnostic rate of FNB was higher than that of FNA (94.6% vs 89.6%). A large retrospective study involving 3020 patients with solid lesions (71.3% of whom were pancreatic masses) showed that the diagnostic performance of EUS-FNB was superior to that of EUS-FNA [Citation20]. Another meta-analysis containing 11 studies also showed similar results [Citation21]. In the future, research can be conducted to compare the diagnostic capabilities of FNA and FNB in GP, to obtain a more accurate diagnosis and to develop treatment plans to avoid unnecessary surgical treatment.

4. Differential diagnostic value of EUS in GP

Pancreatic tumors are the main differential diagnosis that must be considered for GP. Other potential differential diagnoses include duodenal tumors, cholangiocarcinoma of the distal common bile duct, periampullary cancer and autoimmune pancreatitis at the same anatomical location [Citation22, Citation23].

Owing to atypical clinical symptoms, non-specific duodenal wall thickening under endoscopy and overlapping imaging symptoms pose great challenges in the differential diagnosis of GP and pancreatic tumors. Kalb et al. [Citation24] reported three diagnostic criteria for GP on MRI: thickening of the medial duodenal wall, cysts in the duodenal wall and groove area and late enhancement of the second duodenal segment. The diagnostic accuracy of GP based on these three criteria was 87.2%, and the negative predictive value of pancreatic cancer was 92.2%. Given the central role of changes in the duodenal wall in the differential diagnosis of GP and pancreatic tumors, performing MRI is necessary if MRI examination and EUS findings do not provide a definitive answer. Additionally, EUS-guided biopsy is useful in cases of imaging confusion. GP is usually manifested as hypoechoic and uneven masses infiltrating the duodenal wall with calcification and cystic changes by EUS. Most of the masses in GP are lamellar, while pancreatic cancer is round and irregular. The biliary stricture of GP is smooth and long, while that of pancreatic cancer is abrupt and short [Citation25]. Cystic changes in the duodenal wall are commonly seen in GP. The FNA manifestation of the lesion site is non-specific mild or moderate inflammation. Jun et al. [Citation18] found that patients with elevated CA199 and mass-like lesions displayed on multi-slice spiral CT are more likely to be diagnosed with pancreatic tumors, and recommended the use of EUS-FNA in diagnosis for such patients. It can be said that when the FNA result is malignant, EUS tissue sampling may be decisive, but when the FNA result is benign, the possibility of sampling error must always be considered. However, in complex cases, the differential diagnostic value of imaging and endoscopic examination is limited, and a clear diagnosis ultimately requires pathological confirmation. Dhali et al. reported the rare case of a 49-year-old man with persistent upper abdominal pain and a history of alcohol abuse. Physical and laboratory examinations revealed no significant abnormalities, and EUS-FNA revealed chronic inflammatory cells. GP was highly suspected based on endoscopic and imaging examinations. However, the patient underwent pancreatoduodenectomy and histopathological examination revealed mixed neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine tumors. If only radiology and FNA results were considered for this patient, an inaccurate diagnosis might have been made, which would have proven fatal. This indicates that, although FNA can provide biopsy pathological results and is relatively accurate, false negatives may still occur due to the small sample size taken during biopsy and the technical level of the operators. Further, the coexistence of GP and pancreatic tumors should be taken into account as well. Patriti et al. [Citation26] showed that preoperative CT, MRI and EUS were consistent with a diagnosis of GP. Differentiation between simple GP and GP with malignant tumors relies only on postoperative pathological diagnosis, and GP is less common than pancreatic tumors [Citation17, Citation22]. For any suspected pancreatic head mass, the possibility of a pancreatic tumor should be carefully ruled out before diagnosing a GP. The diagnosis of GP must be made with great caution. Combining relevant clinical manifestations, laboratory examination results, imaging results, especially EUS and EUS-FNA results, can generally accurately diagnose GP and differentiate it from other diseases, but special cases must be kept in mind at all times.

5. Therapeutic value of EUS in GP

Although GP is a special type of chronic pancreatitis, its treatment principles are similar to other types, including nonsurgical, endoscopic and surgical treatments (). Conservative nonsurgical treatment is suitable for the early acute stage of the disease, and includes quitting smoking and alcohol consumption, restoring pancreatic function and using painkillers. However, the efficacy of these treatments is usually relatively short-term [Citation27].

Table 3. Studies according to type of treatment (surgical versus endoscopic versus medical treatment).

According to the high-resolution images provided by EUS, it has guiding significance for the selection of GP treatment methods. Surinder et al. retrospectively evaluated the EUS examination results of 17 GP patients who initially received conservative treatment and then underwent surgery on unresponsive patients. There were 12 patients with pure GP (70.5%) and five patients with segmental GP (29.5%). Fourteen patients (82.3%) responded to conservative treatment (Group1) and three patients (17.7%) required surgery (Group2). In the EUS examination, there was no statistically significant difference in the thickening of the duodenal wall and pancreaticoduodenal area, as well as changes in the pancreatic head between the two groups of EUS results. The incidence of cysts in the duodenal wall and groove area in Group1 was higher than that in the Group2 (92.8% vs 33.3%; p = 0.06; 78.5% vs 0%; p = 0.02), indicating that patients with cystic GP seem more likely to respond to conservative treatment [Citation54].

In recent years, endoscopic therapy has been increasingly used in the treatment of GP. Endoscopic treatment methods include pancreatic duct drainage, stenosis dilation and cyst drainage; these should be selected based on the patient’s actual situation. Isayama et al. [Citation55] reported a patient with obstruction of the minor duodenal papilla due to disordered secretion of pancreatic juice. Symptoms were quickly relieved through successful placement of a minor duodenal papilla stent under endoscopy, and there was no recurrence for more than 12 months 6 weeks after stent removal. However, the long-term efficacies of these treatments remain unclear. Endoscopic stent placement can relieve stenosis in patients with GP and duodenal obstruction. Although the incidence of adverse events is very low, delayed iatrogenic perforation due to stent placement can occur [Citation56]. Endoscopic cyst drainage has also achieved good results in some patients; however, this method is only applicable to cases with few non-dispersed, large and shallow cysts [Citation57]. In patients with multiple, small and deep cysts, the recurrence rate after drainage is high [Citation29, Citation58]. Presently, the success rates of endoscopic treatment vary among different authors; only 37.5% (6/16) of the patients treated with endoscopy by Rebours et al. [Citation32] achieved complete success. However, Arvanitakis et al. [Citation37] achieved complete clinical success in nearly 80% of patients by combining endoscopic and drug therapies. In addition to the high recurrence rate of endoscopic treatment, endoscopic drainage of cysts may be difficult if the patient has obvious scars on the duodenal pancreatic head.

If the symptoms of patients with conservative management and endoscopic treatment do not improve significantly and it is difficult to distinguish them from malignant tumors, surgery should be considered. Surgical methods included pylorus-sparing pancreaticoduodenectomy, pancreas-sparing duodenectomy, duodenum-sparing pancreatectomy and pancreaticoduodenectomy. Egorov et al. [Citation38] evaluated different surgical methods in 52 patients with GP; 29 underwent pancreatoduodenectomy, 10 underwent pancreas-sparing duodenectomy and five underwent duodenum-sparing pancreatectomy. Among these, 79%, 90% and 40% of patients, respectively, experienced complete relief of symptoms. Although the results were not significantly different, which may be due to the relatively small number of patients included, duodenum-sparing pancreatectomy appears to be ineffective in patients with GP, possibly because of incomplete resection of the groove area. Regarding the choice of surgical method, pancreaticoduodenectomy remains the most effective because the diseased tissue is completely removed. The presence of persistent pain and/or pancreatic insufficiency (weight loss, fat leak or diabetes) can be attributed to the severe inflammation and fibrosis changes observed in the pancreatic head of GP patients, in which pancreatoduodenectomy can alleviate symptoms and lead to appropriate weight gain [Citation31]. Levenick et al. [Citation36] concluded that surgical resection leads to a reduction in pain symptoms, severity, reduced demand for opioids and weight gain in symptomatic GP patients. Pancreaticoduodenectomy not only treats the disease, but also improves the quality of life of patients. However, pancreatoduodenectomy has a high incidence of adverse events (pancreatic endocrine and exocrine dysfunction) and a high mortality rate (1–5%); therefore, pancreatoduodenectomy is not a first-line option for many patients with GP [Citation29]. Balduzzi et al. [Citation46] did show that pancreaticoduodenectomy is indeed related to the increase in the incidence of postoperative diabetes. Previous research suggests that other surgeries aim to alleviate symptoms by draining cysts or forming intestinal bypasses, but cannot fundamentally prevent recurrence. However, a recent retrospective analysis conducted by Oleksandr et al. [Citation59] on 153 GP patients with only pancreatic head enlargement showed that for GP patients with only pancreatic head enlargement, preserving duodenal pancreatectomy and pancreaticoduodenectomy had similar pain control effects, but the former had a lower incidence of complications and shorter hospital stay. A study conducted by Vyacheslav et al. [Citation48] showed that the safety and efficacy of preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy for pure GP patients are similar to pancreaticoduodenectomy, and may be the best method for treating pure GP patients. Because pure GP is a duodenal disease, pancreaticoduodenectomy may be an over treatment for this disease. Early detection of such patients provides an opportunity for pancreatic conserving surgery.

6. Discussion and conclusions

Therefore, based on various comprehensive considerations, we conclude that a step-by-step approach may be more suitable for treating GP. Conservative management and endoscopic treatment may ensure treatment efficacy and reduce the incidence of adverse events. However, we still need to consider the indications for surgical treatment.

With the continuous improvement in medical institutions’ understanding of GP, diagnosis and treatment methods for GP are constantly improving. As GP is difficult to diagnose and differentiate from cancer by CT and MRI alone, EUS-FNA can provide more accurate biopsy results to clarify the diagnosis, and many patients can achieve complete clinical remission through endoscopic treatment. In summary, EUS has unique value in both the diagnosis and treatment of GP. Clinicians need to be well-versed in the advantages and limitations of EUS for GP diagnosis to select the most suitable imaging diagnostic method for different cases and to reduce the unnecessary waste of medical resources.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, Yumo She and Nan Ge; Methodology, Yumo She and Nan Ge; Formal Analysis, Yumo She; Investigation, Yumo She.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Yumo She; Writing – Review & Editing, Nan Ge; Supervision, Nan Ge.

Institutional review board statement

Not applicable.

Informed consent statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants in this study. We are also grateful to the hospital staff who provided perspective and advice during the preparation of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tezuka K, Makino T, Hirai I, et al. Groove pancreatitis. Dig Surg. 2010;27(2):1–11. doi: 10.1159/000289099.

- Jani B, Rzouq F, Saligram S, et al. Groove pancreatitis: a rare form of chronic pancreatitis. N Am J Med Sci. 2015;7(11):529–532.

- Okasha HH, Gouda M, Tag-Adeen M, et al. Clinical, radiological, and endoscopic ultrasound findings in groove pancreatitis: a multicenter retrospective study. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2023;34(7):771–778. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2023.22875.

- Fléjou JF, Potet F, Molas G, et al. Cystic dystrophy of the gastric and duodenal wall developing in heterotopic pancreas: an unrecognised entity. Gut. 1993;34(3):343–347. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.3.343.

- Manzelli A, Petrou A, Lazzaro A, et al. Groove pancreatitis. A mini-series report and review of the literature. JOP. 2011;12(3):230–233.

- Kwak SW, Kim S, Lee JW, et al. Evaluation of unusual causes of pancreatitis: role of cross-sectional imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2009;71(2):296–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.04.006.

- Shanbhogue AK, Fasih N, Surabhi VR, et al. A clinical and radiologic review of uncommon types and causes of pancreatitis. Radiographics. 2009;29(4):1003–1026. doi: 10.1148/rg.294085748.

- Blasbalg R, Baroni RH, Costa DN, et al. MRI features of groove pancreatitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(1):73–80. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1244.

- Okasha H, Wahba M. EUS in the diagnosis of rare groove pancreatitis masquerading as malignancy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92(2):427–428. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.02.030.

- Oría IC, Pizzala JE, Villaverde AM, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis of pancreatoduodenal groove pathology: report of three cases and brief review of the literature. Clin Endosc. 2019;52(2):196–200. doi: 10.5946/ce.2018.097.

- de Tejada AH, Chennat J, Miller F, et al. Endoscopic and EUS features of groove pancreatitis masquerading as a pancreatic neoplasm. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68(4):796–798. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.02.015.

- Desai GS, Phadke A, Kulkarni D. Cystic dystrophy of the duodenum due to heterotopic pancreas – a case report and review of literature. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10: pd11–pd13.

- Gábos G, Nicolau C, Martin A, et al. Groove pancreatitis-tumor-like lesion of the pancreas. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(5):866. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13050866.

- Bonatti M, De Pretis N, Zamboni GA, et al. Imaging of paraduodenal pancreatitis: a systematic review. World J Radiol. 2023;15(2):42–55. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v15.i2.42.

- Jovanovic I, Knezevic S, Micev M, et al. EUS mini probes in diagnosis of cystic dystrophy of duodenal wall in heterotopic pancreas: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(17):2609–2612. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i17.2609.

- Rana SS, Sharma R, Guleria S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) elastography and contrast enhanced EUS in groove pancreatitis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2018;37(1):70–71. doi: 10.1007/s12664-017-0802-0.

- Patel BN, Brooke Jeffrey R, Olcott EW, et al. Groove pancreatitis: a clinical and imaging overview. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2020;45(5):1439–1446. doi: 10.1007/s00261-019-02239-1.

- Jun JH, Lee SK, Kim SY, et al. Comparison between groove carcinoma and groove pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2018;18(7):805–811. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2018.08.013.

- Wong T, Pattarapuntakul T, Netinatsunton N, et al. Diagnostic performance of endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition by EUS-FNA versus EUS-FNB for solid pancreatic mass without ROSE: a retrospective study. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20(1):215. doi: 10.1186/s12957-022-02682-3.

- Bang JY, Kirtane S, Krall K, et al. In memoriam: fine-needle aspiration, birth: fine-needle biopsy: the changing trend in endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition. Dig Endosc. 2019;31(2):197–202. doi: 10.1111/den.13280.

- Renelus BD, Jamorabo DS, Boston I, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy needles provide higher diagnostic yield compared to endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration needles when sampling solid pancreatic lesions: a meta-analysis. Clin Endosc. 2021;54(2):261–268. doi: 10.5946/ce.2020.101.

- Pallisera-Lloveras A, Ramia-Ángel JM, Vicens-Arbona C, et al. Groove pancreatitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107(5):280–288.

- Castell-Monsalve FJ, Sousa-Martin JM, Carranza-Carranza A. Groove pancreatitis: MRI and pathologic findings. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33(3):342–348. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9245-x.

- Kalb B, Martin DR, Sarmiento JM, et al. Paraduodenal pancreatitis: clinical performance of MR imaging in distinguishing from carcinoma. Radiology. 2013;269(2):475–481. doi: 10.1148/radiology.13112056.

- Gabata T, Kadoya M, Terayama N, et al. Groove pancreatic carcinomas: radiological and pathological findings. Eur Radiol. 2003;13(7):1679–1684. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1743-1.

- Patriti A, Castellani D, Partenzi A, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma in paraduodenal pancreatitis: a note of caution for conservative treatments. Updates Surg. 2012;64(4):307–309. doi: 10.1007/s13304-011-0106-3.

- Levenick JM, Gordon SR, Sutton JE, et al. A comprehensive, case-based review of groove pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2009;38(6):e169–e175. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ac73f1.

- Pessaux P, Lada P, Etienne S, et al. Duodenopancreatectomy for cystic dystrophy in heterotopic pancreas of the duodenal wall. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30(1):24–28. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(06)73073-1.

- Jouannaud V, Coutarel P, Tossou H, et al. Cystic dystrophy of the duodenal wall associated with chronic alcoholic pancreatitis. Clinical features, diagnostic procedures and therapeutic management in a retrospective multicenter series of 23 patients. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30(4):580–586. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(06)73231-6.

- Tison C, Regenet N, Meurette G, et al. Cystic dystrophy of the duodenal wall developing in heterotopic pancreas: report of 9 cases. Pancreas. 2007;34(1):152–156. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000246669.61246.08.

- Rahman SH, Verbeke CS, Gomez D, et al. Pancreatico-duodenectomy for complicated groove pancreatitis. HPB (Oxford). 2007;9(3):229–234. doi: 10.1080/13651820701216430.

- Rebours V, Lévy P, Vullierme MP, et al. Clinical and morphological features of duodenal cystic dystrophy in heterotopic pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(4):871–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01091.x.

- Jovanovic I, Alempijevic T, Lukic S, et al. Cystic dystrophy in heterotopic pancreas of the duodenal wall. Dig Surg. 2008;25(4):262–268. doi: 10.1159/000148133.

- Casetti L, Bassi C, Salvia R, et al. “Paraduodenal” pancreatitis: results of surgery on 58 consecutives patients from a single institution. World J Surg. 2009;33(12):2664–2669. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0238-5.

- Kim JD, Han YS, Choi DL. Characteristic clinical and pathologic features for preoperative diagnosed groove pancreatitis. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;80(5):342–347. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2011.80.5.342.

- Levenick JM, Sutton JE, Smith KD, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for the treatment of groove pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(7):1954–1958. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2214-4.

- Arvanitakis M, Rigaux J, Toussaint E, et al. Endotherapy for paraduodenal pancreatitis: a large retrospective case series. Endoscopy. 2014;46(7):580–587. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365719.

- Egorov VI, Vankovich AN, Petrov RV, et al. Pancreas-preserving approach to “paraduodenal pancreatitis” treatment: why, when, and how? Experience of treatment of 62 patients with duodenal dystrophy. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:185265–185217. doi: 10.1155/2014/185265.

- Zaheer A, Haider M, Kawamoto S, et al. Dual-phase CT findings of groove pancreatitis. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83(8):1337–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.05.019.

- Arora A, Rajesh S, Mukund A, et al. Clinicoradiological appraisal of ‘paraduodenal pancreatitis’: pancreatitis outside the pancreas! Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2015;25(3):303–314. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.161467.

- Lekkerkerker SJ, Nio CY, Issa Y, et al. Clinical outcomes and prevalence of cancer in patients with possible groove pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(11):1895–1900. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13376.

- de Pretis N, Capuano F, Amodio A, et al. Clinical and morphological features of paraduodenal pancreatitis: an Italian experience with 120 patients. Pancreas. 2017;46(4):489–495. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000781.

- Aguilera F, Tsamalaidze L, Raimondo M, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy and outcomes for groove pancreatitis. Dig Surg. 2018;35(6):475–481. doi: 10.1159/000485849.

- Chantarojanasiri T, Isayama H, Nakai Y, et al. Groove pancreatitis: endoscopic treatment via the minor papilla and duct of santorini morphology. Gut Liver. 2018;12(2):208–213. doi: 10.5009/gnl17170.

- Ooka K, Singh H, Warndorf MG, et al. Groove pancreatitis has a spectrum of severity and can be managed conservatively. Pancreatology. 2021;21(1):81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2020.11.018.

- Balduzzi A, Marchegiani G, Andrianello S, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for paraduodenal pancreatitis is associated with a higher incidence of diabetes but a similar quality of life and pain control when compared to medical treatment. Pancreatology. 2020;20(2):193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2019.12.014.

- Tarvainen T, Nykänen T, Parviainen H, et al. Diagnosis, natural course and treatment outcomes of groove pancreatitis. HPB (Oxford). 2021;23(8):1244–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2020.12.004.

- Egorov V, Petrov R, Schegolev A, et al. Pancreas-preserving duodenal resections vs pancreatoduodenectomy for groove pancreatitis. Should we revisit treatment algorithm for groove pancreatitis? World J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;13(1):30–49. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i1.30.

- Teo J, Suthananthan A, Pereira R, et al. Could it be groove pancreatitis? A frequently misdiagnosed condition with a surgical solution. ANZ J Surg. 2022;92(9):2167–2173. doi: 10.1111/ans.17939.

- Değer KC, Köker İH, Destek S, et al. The clinical feature and outcome of groove pancreatitis in a cohort: a single center experience with review of the literature. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2022;28(8):1186–1192. doi: 10.14744/tjtes.2022.12893.

- Kulkarni CB, Moorthy S, Pullara SK, et al. CT imaging patterns of paraduodenal pancreatitis: a unique clinicoradiological entity. Clin Radiol. 2022;77(8):e613–e619. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2022.04.008.

- Dhali A, Ray S, Ghosh R, et al. Outcome of Whipple’s procedure for groove pancreatitis: a retrospective cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;79:104008.

- Vujasinovic M, Pozzi Mucelli R, Grigoriadis A, et al. Paraduodenal pancreatitis – problem in the groove. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2022;58:1–8. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2022.2036806.

- Rana SS, Bush N, Gupta R. Conservative or surgical treatment for groove pancreatitis: can endoscopic ultrasound guide the management strategy? HPB (Oxford). 2021;23(11):1769–1770. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2021.06.001.

- Isayama H, Kawabe T, Komatsu Y, et al. Successful treatment for groove pancreatitis by endoscopic drainage via the minor papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61(1):175–178. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02460-5.

- Taibi A, Durand Fontanier S, Derbal S, et al. What is the ideal indwelling time for metal stents after endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastrojejunostomy? Case report of delayed iatrogenic perforation with a review of the literature. Dig Endosc. 2020;32(5):816–822. doi: 10.1111/den.13645.

- Beaulieu S, Vitte RL, Le Corguille M, et al. [Endoscopic drainage of cystic dystrophy of the duodenal wall: report of three cases]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28(11):1159–1164. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(04)95198-6.

- Thürlimann B, Senn HJ. [Safety problems in the handling of cytostatics]. Ther Umsch. 1988;45(6):403–407.

- Usenko O, Khomiak I, Khomiak A, et al. Duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection or pancreatoduodenectomy for the surgical treatment of paraduodenal pancreatitis: a retrospective cohort study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2023;408(1):178. doi: 10.1007/s00423-023-02917-1.