Abstract

Background

While Cardiac Rehabilitation (CR) programs have shown effectiveness in improving cardiac outcomes, there is limited understanding of how patients perceive and adapt to these interventions. Furthermore, alternative modes of delivering CR that have received positive evaluations from participants remain underexplored, yet they have the potential to enhance CR uptake.

Objectives

To explore the patient experience in CR programmes following Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) and describe their adaptive processing.

Patients and Methods

This qualitative study was conducted at a nationally certified centre in China between July 2021 and September 2022, encompassing three stages: in-hospital, centre-based, and home-based CR programs. Purposive sampling was used to select eligible AMI patients for in-depth semi-structured interviews. The interview outline and analytical framework were aligned with the key concepts derived from the middle-range theory of adaptation to chronic illness and the normalization process theory. The findings were reported following the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist.

Results

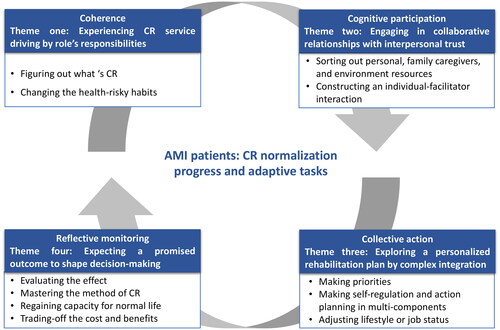

Forty AMI patients were recruited. Four main themes describing the process of AMI patients normalizing CR intervention were identified, including (1) experiencing CR service driving by role’s responsibilities, (2) engaging in collaborative relationship based on interpersonal trust, (3) exploring a personalized rehabilitation plan by complex integration, and (4) expecting a promised outcome to shape decision-making.

Conclusion

Integrated care interventions for AMI patients could benefit from a collaborative co-designed approach to ensure that CR interventions are normalized and fit into patients’ daily lives. Organizational-level CR services should align with the rehabilitation needs and expectations of patients.

Introduction

An acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a life-threatening cardiac presentation that can be a traumatic and stressful experience and is associated with subsequent chronic illness adversely affecting the patient and their family [Citation1]. Various cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs have been proposed, aligning with guideline recommendations and utilizing different delivery models, such as in-hospital, centre-based, home-based, and technology-supported CR for AMI patients [Citation2–4]. However, evidence suggests that a hybrid CR is more effective [Citation3, Citation5, Citation6]. Future research priorities include integrating patients’ needs and promoting active participation in CR to achieve better cardiovascular outcomes [Citation3, Citation4]. The subjective evaluation of AMI-related stressors and CR treatment in relation to personal perception and coping efforts have been neglected in the research of improvement of CR uptakes.

Despite the high prevalence of AMI in China, there is a scarcity of evidence-based and scalable CR interventions and services [Citation7]. Recognizing this gap, the Cardiovascular Disease Quality Initiative (CDQI) was launched in 2019 with the aim of establishing certification standards for CR centres. However, similar to other countries, China continues to face challenges such as fragmented CR services and low rates of CR participation [Citation8]. Extensive research has been conducted on the barriers to CR participation [Citation3, Citation4, Citation9]. One review identified physician-related (i.e. low CR referral rates and inadequate physician endorsement), patient-related (i.e. gender and racial disparities, medical comorbidities, socioeconomic factors, and psychological factors), and system-related (i.e. travel and transportation, cost of attendance, and fragmented care) factors [Citation10]. Additionally, studies have highlighted patients’ expectations for CR programs, such as communication with specialists, pre-program training, and periodic visits to maintain motivation and adherence [Citation9]. While there is evidence describing the motivation, attitude, and experiences of patients towards CR, little is known about how AMI patients appraise the stress of their disease, adapt to CR interventions, and adjust to the management of the hospital-to-home transition. Alternative delivery modes that have received positive evaluations from CR participants remain largely unexplored.

One area seen as a way of improving CR attendance is the use of adaptive tasks which is how an individual appraises disease-related stressors and shapes coping abilities whilst they manage their health condition and health-related outcomes [Citation11, Citation12]. Adaptive experience includes self-management, management of symptoms, treatment, and emotions, forming relationships with healthcare provides, and maintaining a positive self-image, relating to family members and friends, preparing for an uncertain future[Citation13, Citation14]. Considering the cultural context, middle-range theory of adaptation to chronic illness (MRT-ACI) was generated through rigorous mix-methods research [Citation15] and has been successfully used to understand the adaptation processing of Chinese patients[Citation16–18]. Another approach to explaining the adaptive experience of patients is the use of Normalization Process Theory (NPT), which elucidates the tasks involved in organizing and operationalizing healthcare practices by focusing on four key actions: coherence, cognitive participation, collective action, and reflexive monitoring [Citation19]. Applying NPT can offer insights into the mechanisms that facilitate successful adaptation and integration of healthcare practices into patients’ daily lives [Citation20, Citation21]. By combining the key concepts of MRT-ACI and NPT, we can gain a comprehensive understanding of how AMI patients adapt and engage with CR and document their proactive changes.

This study aimed to explore the patient experience in CR programmes following AMI event and to describe their adaptive processing. The specific objectives were: (1) to identify the types of adaptive tasks that reflect subjective evaluations of AMI patients regarding the demands imposed by disease management, (2) to describe the manifestations of adaptive tasks throughout the progress of CR, and (3) to elucidate the normalization process of CR interventions and how they fit into the daily lives of AMI patients.

Patients and methods

Study design

This descriptive qualitative study was conducted as part of an integrated cardiac rehabilitation program with a hybrid approach at a nationally certified Cardiac Rehabilitation Centre (CRC) in Shanghai [Citation22]. Utilizing a constructionist perspective, qualitative descriptive studies generate data that elucidate how individuals actively construct their understanding and knowledge of the world through their experiences within a specific context, encompassing key aspects such as ‘who, what, and where’ characteristics, observed through their actions [Citation23, Citation24]. This study employed semi-structured interviews supported by a comprehensive analysis of observational data across various stages of cardiac rehabilitation. The analysis integrated quantitative data, records of periodic follow-up clinic visits, and textual information (). Thus, this design was selected for its appropriateness and reliability in providing a comprehensive and detailed understanding of individuals’ perceptions regarding CR treatment [Citation25], while acknowledging their knowledge and contributions, potentially informing clinical practices [Citation24, Citation26]. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist was applied [Citation27] (see Supplementary File).

Table 1. Descriptions of three stages of CR service and patients’ involvement.

Theoretical framework

This study employed the NPT as a conceptual framework [Citation19], to investigate the adaptive tasks performed by AMI patients in different CR programs and to describe the dynamic changes throughout the CR process. The NPT framework includes four mechanisms that were applied within the CR contexts. Coherence focused on identifying the meaningful aspects of CR interventions. Cognitive participation involved the enrolment and engagement of individuals, families, healthcare professionals, and other relevant stakeholders. Collective action encompassed interactions with existing therapeutic interventions, daily life routines, social networks, and other health promotion activities. Reflective monitoring entailed the appraisal work aimed at assessing the quality and effectiveness of the services provided. Subsequently, a predefined coding reference was summarized (Supplementary file, Table S1).

Study setting and patients

A purposive sampling approach was used to recruit participants between July 2021 to September 2022. To ensure adequate exposure to the CR program and avoid recall errors, participants were recruited at three distinct stages: the in-hospital stage for clinical rehabilitation, the centre-based stage for outpatient rehabilitation, and the home-based stage for post-cardiac rehabilitation (see ). Two cardiac therapists facilitated the recruitment of patients who were: (1) aged 18 years or older; (2) diagnosed with AMI by a cardiologist and discharged from hospital; (3) completion of prescribed CR-physical exercise intervention under therapist supervision within the chosen CR programs; (4) fluent in Mandarin or the local dialect; and (5) willing to share their experience.

Data collection

provides an overview of the three CR stages, patient involvement, and data collection methodologies. Data collection was conducted preceding transitions to subsequent CR program phases, encompassing three specific timeframes: within 24 h before hospital discharge, during the final assessment of centre-based rehabilitation, and within the sustainable home environment. Eligible patients were invited by cardiac therapists to participate, and two researchers meticulously gathered pertinent field notes to gain a holistic understanding of each patient’s journey. Subsequently, in-person semi-structured interviews were conducted in a quiet clinical room, with participants consenting to the use of voice recorders. To ensure interview consistency across these stages, we developed a comprehensive outline based on the concept of adaptation derived from the MRT-ACI that included the questions: How do you cope with and adapt to the AMI in your life? What issues did you have adapting after your heart attack? What tasks have you done to help manage cardiac rehabilitation? What is your opinion on an on-going CR program? The collection of patient data proceeded in tandem with the coding and interpretation processes. We determined data saturation by accessing information redundancy during the data analysis phase [Citation28]. To further ensure data completeness, we conducted two additional interviews and no new ideas or themes emerged.

Data analysis

The analysis of qualitative text data within Excel and NVivo software followed the five stages proposed by Pope et al. [Citation29], which include familiarization, identification of a thematic framework, indexing, charting, and mapping, and interpretation. Inductive analysis was utilized to derive themes from the textual transcripts [Citation30]. To ensure consistency and accuracy, two authors independently coded all the data and cross-checked their coding. Patients’ health status was validated with the cardiac therapists. The interview findings underwent extensive review and discussion among the CR team members to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the adaptive tasks in CR. Any ambiguities or discrepancies that arose during the analysis process were resolved through thorough discussions within the research team.

Rigour

The theories of MRT-ACI and NPT served as the theoretical foundation and framework for the study, providing consistency in key concepts and facilitating a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. To address potential bias associated with using a purposive sample, we enlisted the assistance of trained investigators who were attending nurses and cardiac therapists. Their expertise and experience in cardiac care helped ensure the inclusion of a diverse range of participants with varying perspectives and experiences. Additionally, a blinded approach was adopted during participant selection, minimizing preconceived notions or biases that may have influenced the selection process. In addressing potential memory bias in patient reports, complementary data collection methods, such as surveys, digital recorded histories, and patient-generated e-consultation texts, were employed to cross-check and enhance the understanding of patients’ expressions during interviews. To enhance the rigor and validity of the study, a team of trained researchers, including a university lecturer with a PhD degree and a clinical nursing expert as a master’s candidate, collaborated in the process of data analysis and interpretation. Moreover, a multi-professional research team allowed for a comprehensive examination of the data from different perspectives, ensuring thorough and reliable analysis. These measures aimed to strengthen the rigour, credibility, and validity of the findings, ensuring they were based on a diverse and representative sample of the population of interest.

Ethical statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine affiliated with Renji Hospital (No. KY2021-098-B-CR-01) and conformed with the Declaration of Helsinki. The participants provided their informed written consent to participate in this study and agreed on the interview record and data usage for research purpose.

Results

Participants characteristics

The study involved forty patients of Han ethnicity with an average age of 55.68 (SD ±12.33), whose characteristics are described in . All forty patients were recruited, and a total of 44 in-person interviews were conducted, with durations ranging from 45 to 65 min. Of the 16 participants who completed in-hospital CR rehab, they reported feeling prepared for discharge based on a validated scale. The main factors that significantly influenced their decision-making process regarding hospital discharge were primarily related to improved physical function and feeling like a burden on their family. Additionally, from the 19 participants who achieved the therapeutic goal during centre-based rehabilitation, their follow-up clinical visits were accessed and analysed. In the post-cardiac rehabilitation phase, four participants were retained from the centre-based CR program, and an additional five participants were interviewed.

Table 2. Characteristics of participants (n = 40).

Normalizing adaptive tasks of AMI patients in CR process

illustrates the synthesis of four descriptive themes along with the corresponding sets of adaptive tasks derived from patients’ experiences. These themes are aligned with four interconnected concepts derived from the NPT, including experiencing CR service, engaging in a collaborative relationship, exploring a personalized rehabilitation plan, and expecting a promised outcome. While these themes remain consistent, their manifestations vary throughout the different CR stages, influenced by situational demands and the degree of integration of CR into patients’ daily lives ().

Table 3. AMI patients’ adaptive tasks across different CR stages.

Theme 1: Experiencing CR service driving by role’s responsibilities

Figure out what’s CR

Patients who were educated about the causes, treatments, and consequences of their illness have shown adaptive efforts in making CR an effective approach to post-AMI treatment. After receiving health education of CR from hospital staff, almost all patients reflected on their past health-related behaviours and would like to figure out what is CR interventions.

I would like to know more about my physical condition and the severity of my illness. I have been avoiding dealing with my health problems. I used to think that it would be okay to be slightly overweight and that I still have time, but my health problems are increasing……. Does participating in this rehabilitation program really benefit my heart? Will I have to continue doing it for a long-term period? (In-hospital rehab, P6)

After learning about therapeutic approaches (CR) from a cardiac specialist in Beijing and gradually understanding the scope of CR services, I discovered its availability in Shanghai several years later. I find it reasonable and suitable for addressing my health concerns. (Transitioning from centre-based to home-based rehab, P3)

Changing the health-risky habits

Family and work responsibilities were significant motivators for individuals to enrol in CR programs and changing their lifestyles. The most significant reason they revealed was to decrease the burden of illness on their families and reduce the frequency of needing assistance, or ‘Tian Ma Fan’ in Chinese. Many patients felt guilty about imposing on their families, especially their children, who had to take time off work or adjust schedules to care for them in the hospital.

Is there a specific intervention that is particularly suitable for promoting heart rehabilitation (after discharge)? My child is only seven years old, and I’m quite concerned. Additionally, I have to take care of my ageing parents, which adds to my concerns. I have a lot on my plate to worry about. (In-hospital rehab, P13)

Some individuals felt a sense of responsibility to remind their loved ones and even volunteered to promote healthy behaviours among others.

(After being discharged and returning home) I feel the need to encourage my family and friends to prioritize their health by taking care of their bodies and avoiding unhealthy habits such as staying up late, smoking, and excessive drinking. I have noticed that they face significant work pressure in their daily lives, and it’s crucial to protect themselves and be mindful of potential heart problems. (In-hospital rehab, P10)

Theme 2: Engaging in collaborative relationship based on interpersonal trust

AMI patients demonstrated a proactive approach in identifying and utilizing personal, family caregiver, and environmental resources, which facilitated the development of individual-facilitator interactions.

Sorting out personal, family caregivers’, and environmental resources

Patients recognized that own role was crucial in taking responsibility for health management and sought out appropriate resources for support, especially older patients. They relied on their children to facilitate the translation of complex CR interventions, such as ‘You (nurses) could talk to my son. He will tell me what I should do and how to do it’. (In-hospital rehab, P3). Conversely, younger patients tended to seek direct access to healthcare professionals for their needs.

Will you (nurses) remind me the exact time for centre-based rehab? I have no ideas when I could stop the CR program but am worried about something wrong with my heart again. (In-hospital rehab, P1).

Constructing an individual-facilitator interaction

Furthermore, patients valued the contributions and active involvement of healthcare professionals in their care. They actively sought to establish a trusting relationship and sought confirmation from healthcare professionals to clarify their responsibilities within the CR interventions. This process also boosted their confidence, sense of empowerment, and commitment to adhering to the prescribed CR treatment.

During each communication with my doctors, I explain my reasons for my concerns one by one, which I believe is an efficient way to facilitate our discussion. In turn, they discuss their plans with me before implementing them, which makes it a collaborative process between us that requires coordination. (Centre-based rehab, P2)

Throughout both the centre-based and home-based CR stages, many patients were able to involve their spouses in the CR program. This action not only contributed to patients’ enhanced physical well-being but also strengthened their relationships and provided valuable emotional support. Considering their children’s busy schedules, patients mentioned that their children may not have sufficient time to accompany them in their CR activities. However, they found alternative ways to support their parents’ health behaviours by providing devices such as drug boxes, blood testing equipment, and heart rate monitors. These tools served as guides for their parents to adopt new health behaviours and manage their condition effectively.

Theme 3: Exploring a personalized rehabilitation plan by complex integration

AMI patients showed a strong understanding of the importance of medication, diet, and exercise among CR interventions in effectively managing their disease. They identified these areas as priorities and subsequently engaged in self-regulation and action planning to incorporate them into daily lives, leading to significant changes in their lifestyle and job status.

Making priorities

All patients in different CR phases prioritized medication, dietary choices, and affordable physical activities. These three factors were also the most common reasons for patients to consult during clinical follow-ups and internet consultations throughout the entire CR program.

Could you (nurse) tell me what I should and shouldn’t do during the CR period after my discharge, as well as taking medicine and some precautions regarding my diet? I realize that I can no longer continue my previous habits of drinking and smoking excessively for job-related reasons, staying up late at night and smoking heavily throughout the day. (In-hospital phase, P7)

Making self-regulation and action planning in multi-components

AMI patients enacted a phase of cognitive learning where they needed to practice and explore personalized approaches. They demonstrated varying levels of effort in different aspects, such as monitoring health indicators, managing symptoms, and establishing a daily routine that accommodated their perceived tasks. They emphasized that they had invested a significant amount of time exploring personal strategies for rehabilitation and anticipated to seek guidance and support to ensure they were on the right path towards successful recovery.

I regularly monitor my blood pressure, and it shows stable. During seasonal change, there would be some fluctuations and when I felt uncomfortable. Generally, monitoring of BP is not as frequent, but it depends on the situation. (Centre-base rehab, P3)

Some patients shared positive experiences of incorporating digital approaches into self-management tasks as part of their daily routines. These digital approaches encompassed the use of mobile phones, digital watches, treadmills, and remote ECG devices, assisting in progress monitoring, staying motivated, and enhancing adherence to the prescribed CR program.

…… I had previously bought a (digital) watch that claimed to test blood glucose, blood pressure, and heart rate. However, I discovered that it was providing inaccurate information when I tested it …… So, I decided to change a different product that offers ECG testing, as I believe this method (of that product) makes more sense (in terms of reliability) for health monitoring. (Centre-based rehab, P9)

AMI Patients also engaged in active exploration of self-regulation to cope with emotions. They developed a coping philosophy centred around achieving a sense of balance to deal with AMI illness and normalizing CR interventions. They emphasized the importance of neither completely ignoring oneself nor being excessively self-conscious. Gradually, they came to understand that the process of recovery takes time. They dedicated themselves to engaging in physical exploration and making psychological adjustments, aiming to cultivate a positive interpretation of illness management, establish meaningful life goals, and prioritize emotional well-being.

I approach the topic of life and death with an open mind. (As a policeman) I have witnessed many accidents, which has become a professional habit (to deal with uncertainties). I believe that fate determines the illnesses we may contract and when we will pass away. The only thing we can do is take good care of ourselves. (Centre-base rehab, P1)

Adjusting lifestyles or job status

AMI patients commonly set their sights on achieving short-term milestones as they aimed to be ready for discharge and return to home and work. They engaged in self-reflection and recognized the illness-related stressors associated with unhealthy lifestyles and job strain. This awareness prompted them to take proactive steps to make adjustments in job and life situations.

Depending on my health, I will consider my work situation. My current job is quite demanding, and I often have to socialize with clients and attend parties where drinking is heavily involved. ……. After experiencing this cardiac attack, I am considering switching to a less demanding job. (In-hospital rehab, P6)

Theme 4: Expecting a promised outcome to shape decision-making

Evaluating the effect

AMI patients gained the autonomy to explore personalized care, which encouraged them to pay attention to, and reflect upon, their adaptational outcomes and intervention effectiveness. As patients progressed through CR program and acquired new knowledge and skills through cognitive learning and practice, they gained a deeper understanding of CR functions and their physical limitations. These experiences resulted in increased control and satisfaction with the effects of the intervention and boosted their confidence in maintaining CR-related behaviours.

……Now I can tell the activities such as walking from not a kind of ‘exercise’. …. I started with an exercise intensity of around 60W, and now I am at 73W. If I had continued at this pace, I could have reached 75W or 76W, which is similar to what a healthy person can achieve. This experience has gradually given me confidence…… I have a better understanding of how much (exercise intensity) I can handle. (Centre-based rehab, P3)

Mastering the method of long-term CR

AMI patients received education and training that facilitated automatic reflection on their feelings and the ability to discern between improvements and deteriorations. Consequently, they gradually perceived fewer stressors on their health and developed enhanced coping mechanisms to address challenges. These changes in perception also contributed to a more objective evaluation of CR progress, allowing for a less emotionally influenced assessment.

On Thursday, things didn’t go well… I’m feeling fatigued (after exercising at this level) … It’s still relatively relaxing… I’ve recovered a bit, but it seems like I still need six or seven more sessions to get back to my normal state (the target goal) … Today, I made progress and broke my previous record… (home-based rehab, P6)

Regaining capacity for normal life

Patients consistently assessed the changes in physical energy and psychological strength resulting from the CR program and sought encouraging signs of progress to maintain adherence. They valued the capacities of living with illness (such as go traveling and take care of their grandchildren) and being able to do more things and care for themselves independently considering the status of life course.

Thanks to the CR program, my life and quality of life have undergone a fundamental change. I have been able to achieve "coexisting with disease," which means I have solved the problem of how to live with my illness in a positive way. In comparison to the past eight years, these past two months have brought about an obvious recovery in both my physical body and psychological condition. (Centre-base CR rehab, P2)

Trading-off the cost and benefits

Some patients, particularly older individuals and those closely cared for by children, also expressed worries about the cost. They felt reluctant to undergo further medical procedures and tended to report feeling well, despite potential underlying health issues and poor understanding of CR interventions. However, other patients reported surprises regarding the positive experience and significant benefits they received from CR program.

I felt that this (centre-based CR) was my chance to turn my health around [alleviate the progression of my disease]. This was a crucial turning point for me. If this approach can help achieve the goal of delaying or postponing surgery for 2–3 years, it would be a significant medical breakthrough for our patients. (Centre-based rehab, P2)

Discussion

This study explored which adaptive tasks, referring to the concept of ‘illness perception and response’, were of relevance to AMI patients dealing with CR, and how they were implemented, embedded, and normalized within patients’ life. Consequently, key elements of adaptive tasks include actively seeking meaning in CR experience, engaging with internal and external resources, exploring and establishing a rehabilitation routine, and consistently evaluating the effects of CR based on expectational perceptions. These adaptive tasks in executing CR were exemplified through the operation of generative normalization mechanisms, shaping how AMI patients engaged across the various CR stages.

Our study uncovered that the presence of roles’ responsibilities as a motivator to make AMI patients find the meaning and actively using CR programs. Within Chinese cultural contexts, an individual’s health is often intricately tied to their social role, family expectations, and other obligations [Citation31]. This is supported by the notion that sociocultural norms have a profound influence on patients’ health behaviour changes following cardiac events [Citation32]. Meanwhile, we also identified a noteworthy tendency among patients to prioritize self-sacrifice, neglecting their own needs while expecting increased care from their families. This underlying expectation creates a conflict and is accompanied by feelings of guilt and blame deeply ingrained within family dynamics [Citation33], which in turn affects their illness perception, emotional well-being, and acts as barriers to sustaining the CR interventions. Therefore, it becomes crucial to establish a shared experience that bridges the communication gap and promotes open dialogue among patients, family caregivers, and healthcare professionals. This approach advocates for the co-development of stress-coping strategies to better support patients and their caregivers in managing the challenges of living with a chronic condition [Citation34, Citation35]. Healthcare professionals in the CR team should gain awareness of the significance of patient self-commitment and caregiver engagement, and work towards reaching an agreement on health value and treatment priorities.

Our findings also indicate that AMI patients actively participate in an exploratory process to develop a personalized CR plan, which involves assessing stimuli, formulating coping responses, and engaging in a combination of instrumental and emotional adaptive tasks. AMI patients often experience recollections of cardiac arrest and medical emergencies [Citation1, Citation36], necessitating interventions that incorporate cultural clinical psychology and appropriate illness perception [Citation37, Citation38]. Additionally, consistent with other studies, inadequate health literacy have been linked to negative emotions and a poorer quality of life among individuals with cardiovascular disease [Citation39], and can hinder the understanding of the physiological and psychosocial benefits of CR [Citation40]. By actively involving patients in the exploration and implementation of CR techniques, their health literacy improves over time by cognitive learning, proactive communications with healthcare professionals, and implementing personalized strategies. Furthermore, the development of adaptive coping strategies is facilitated when AMI patients have a strong belief and control in their own health and confidence in themselves, families, and care professionals, enabling them to navigate through the CR treatment and adhere to it [Citation41, Citation42]. However, discrepancies in identified adaptive tasks across the three stages may originate from the individual capacity influenced by factors such as patients’ social demographics, educational knowledge mastery, practical experiences, and familiarity with organizational aspects. This amalgamation of influences significantly moulds patients’ behaviours and decisions [Citation43, Citation44]. Similar to observations in various health service contexts, these factors underscore an ongoing and progressive evolution among patients in their approach to managing their health [Citation11, Citation45, Citation46].

Throughout the entire CR program, this study delves into the mechanisms that normalize CR interventions across different stages, illustrating how these interventions become integrated into patients’ lives with various rehabilitation emphases. It’s essential to recognize that AMI patients hold dynamic expectations and continually evaluate the effects of CR interventions, evolving their understanding of significance over time. This adaptive approach plays a key role in alleviating feelings of lack of control and learning stress experienced by patients, emphasizing the importance of coping efforts and the self-commitment in their CR journey [Citation47]. The effectiveness of such interventions has been demonstrated in studies such as the SMART-CR/SP project [Citation48]. Similarly, in line with previous studies that aimed to overcome barriers to CR using mobile health and related technologies [Citation4, Citation49–51], we observed that the widespread use of WeChat empowered patients to explore and develop personalized approaches and significantly enhanced their autonomy in translating knowledge into practical applications. This valuable contribution provides detailed information for CR interventions that require practical care delivery modes [Citation39].

Strengths and limitations

This study presents empirical evidence supporting the implementation of integrated care for cardiac patients [Citation52], along with theory-testing of MRT-ACI and NPT. By investigating the adaptation challenges experienced by AMI patients during CR delivery, healthcare professionals can develop interventions that are more tailored and effective, thereby increasing patients’ participation and completion rates in CR. Furthermore, this study helps bridge the knowledge gaps between healthcare professionals and patients, addressing potential disparities in information access and understanding among patients.

Despite our attempts to include diverse AMI patients to have a representative sample, our study did not include a comparative analysis between virtual and in-person CR interventions, nor did it specifically explore health inequalities related to participants’ social characteristics. This limits our ability to fully understand the impact of different modes of intervention delivery and how social factors may influence patients’ experiences and uptake of CR service. In terms of the study design, we recruited AMI patients from three stages of the CR process but conducted single-timepoint interviews focusing solely on the ongoing CR program. However, insights gathered from four retained participants across two CR stages suggest that a longitudinal study, encompassing participants engaged in all three stages through a follow-up design, could significantly enhance our understanding. Such an approach would offer a more comprehensive insight into the cognitive and regulatory processes involved in patients’ adaptive capacity throughout their participation in CR-related interventions over time.

Relevance to clinical practice

The findings of this study underscore the importance of incorporating patients’ perspectives and experiences into the design and implementation of CR programs, ultimately contributing to the development of large-scale trials that prioritize person-cantered care, holistic designs, and co-design implications. By tailoring CR programs to answer the complex needs, continuous stress appraisal, and coping process of individual patients, healthcare providers can enhance the effectiveness and relevance of interventions aimed at tackling the multifaceted challenges associated with adapting to CR. This holistic perspective allows for a more nuanced understanding of the factors influencing patients’ engagement and adherence to CR programs. Furthermore, it sets the stage for co-design implications in the development of CR interventions. The collaborative approach taken in considering patients’ viewpoints fosters a sense of control and empowerment among patients, thereby increasing their motivation and engagement in the CR process, ultimately leading to the normalization of CR interventions fitting into their lives.

Conclusion

This study represents an initial effort to implement a holistic design in post-AMI care, considering the complexities of patients’ stress appraisals and the proactive actions of integrated CR. By understanding the adaptive tasks involved in the CR process, valuable insights can be gained from patients’ experiences and effectively utilized in health education and real-world interventions using patient-centred approach. Ultimately, these efforts are expected to result in increased attendance and completion rates of CR programs, as well as improved cardiovascular outcomes.

Authors contributions

Xiyi Wang and Li Xu conceptualized and conducted the study. Xiyi Wang and Geraldine Lee led the writing and revision of the manuscript. Xunhan Qiu was responsible for participants recruitment. Dandan Chen, Ping Zou, and Hui Zhang verified the data extraction and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants and their caregivers for sharing the actual experiences and to acknowledge our research partner and its faculty staff in which Renji Hospital affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. Xiyi Wang would like to thank K.C. Wong Foundation Fellowship to support her research at King’s College London.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The data is available upon a reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Edmondson D, von Känel R. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(4):1–12. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30377-7.

- Dalal HM, Doherty P, McDonagh ST, et al. Virtual and in-person cardiac rehabilitation. BMJ. 2021;373:n1270. doi:10.1136/bmj.n1270.

- Beatty AL, Beckie TM, Dodson J, et al. A new era in cardiac rehabilitation delivery: research gaps, questions, strategies, and priorities. Circulation. 2023;147(3):254–266. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.061046.

- Taylor RS, Dalal HM, McDonagh STJ. The role of cardiac rehabilitation in improving cardiovascular outcomes. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19(3):180–194. doi:10.1038/s41569-021-00611-7.

- Heindl B, Ramirez L, Joseph L, et al. Hybrid cardiac rehabilitation - The state of the science and the way forward. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2022;70:175–182. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2021.12.004.

- Keteyian SJ, Ades PA, Beatty AL, et al. A review of the design and implementation of a hybrid cardiac rehabilitation program: an expanding opportunity for optimizing cardiovascular care. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2022;42(1):1–9. doi:10.1097/HCR.0000000000000634.

- Zhang Z, Pack Q, Squires RW, et al. Availability and characteristics of cardiac rehabilitation programmes in China. Heart Asia. 2016;8(2):9–12. doi:10.1136/heartasia-2016-010758.

- Xu L, et al. Study on influencing factors and effect evaluation of patients with acute myocardial infarction in the cardiac rehabilitation center. J Shanghai Jiao Tong Univ (Medical Science). 2022;42(05):646–652.

- Bakhshayeh S, Sarbaz M, Kimiafar K, et al. Barriers to participation in center-based cardiac rehabilitation programs and patients’ attitude toward home-based cardiac rehabilitation programs. Physiother Theory Pract. 2021;37(1):158–168. doi:10.1080/09593985.2019.1620388.

- Chindhy S, Taub PR, Lavie CJ, et al. Current challenges in cardiac rehabilitation: strategies to overcome social factors and attendance barriers. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2020;18(11):777–789. doi:10.1080/14779072.2020.1816464.

- Moos RH, Holahan CJ. Adaptive tasks and methods of coping with illness and disability (Chapter). Coping with Chronic Illness and Disability: theoretical, Empirical, and Clinical Aspects. 2007: Springer: New York, 107–126.

- Bensing JM, Schreurs KMG, de Ridder DTD, et al. Adaptive tasks in multiple sclerosis: development of an instrument to identify the focus of patients’ coping efforts. Psychol Health. 2002;17(4):475–488. doi:10.1080/0887044022000004957.

- Martz E, Livneh H, Wright B. Coping with chronic illness and disability. 2007: Springer. New York.

- Qiu R, Tang L, Wang X, et al. Life events and adaptive coping approaches to self-management from the perspectives of hospitalized cardiovascular patients: a qualitative study. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:692485. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.692485.

- Wang X, Ye Z. Development of a Middle-range theory of adaptation to chronic illness based on the roy’s model. Chin J Nurs. 2021;56(8):1193–1200.

- Chen D, Zhang H, Shao J, et al. Determinants of adherence to diet and exercise behaviours among individuals with metabolic syndrome based on the capability, opportunity, motivation, and behaviour model: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2023;22(2):193–200. doi:10.1093/eurjcn/zvac034.

- Wang X, Tang L, Howell D, et al. Theory-guided interventions for chinese patients to adapt to heart failure: a quasi-experimental study. Int J Nurs Sci. 2020;7(4):391–400. doi:10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.09.004.

- Wang XY, Shao J, Ye ZH. Understanding and measuring adaptation level among Community-Dwelling patients with metabolic syndrome: a cross-Sectional survey. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:939–947. doi:10.2147/PPA.S248126.

- May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: an outline of normalization process theory. Sociology. 2009;43(3):535–554. doi:10.1177/0038038509103208.

- McNaughton RJ, Steven A, Shucksmith J. Using normalization process theory as a practical tool across the life course of a qualitative research project. Qual Health Res. 2020;30(2):217–227. doi:10.1177/1049732319863420.

- Dalkin SM, Hardwick RJL, Haighton CA, et al. Combining realist approaches and normalization process theory to understand implementation: a systematic review. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1):68. doi:10.1186/s43058-021-00172-3.

- Wang X, Xu L, Lee G, et al. Development of an integrated cardiac rehabilitation program to improve the adaptation level of patients after acute myocardial infarction. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1121563. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1121563.

- Denzin NK, et al. The sage handbook of qualitative research. 2023: Sage Publications, Los Angeles.

- Doyle L, McCabe C, Keogh B, et al. An overview of the qualitative descriptive design within nursing research. J Res Nurs. 2020;25(5):443–455. doi:10.1177/1744987119880234.

- Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qual Health Res. 2003;13(7):905–923. doi:10.1177/1049732303253488.

- Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Titchen A, et al. What counts as evidence in evidence-based practice? J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(1):81–90. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03068.x.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exercise Health. 2019;13(2):201–216. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846.

- Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320(7227):114–116. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Chan EA, Cheung K, Mok E, et al. A narrative inquiry into the Hong Kong chinese adults’ concepts of health through their cultural stories. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(3):301–309. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.06.001.

- Tunsi A, Chandler C, Holloway A. Perspectives on barriers and facilitators to lifestyle change after cardiac events among patients in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2023;22(2):201–209. doi:10.1093/eurjcn/zvac031.

- Bahr HM, Bahr KS. Families and self-Sacrifice: alternative models and meanings for family theory. Social Forces. 2001;79(4):1231–1258. doi:10.1353/sof.2001.0030.

- Thodi M, Bistola V, Lambrinou E, et al. A randomized trial of a nurse-led educational intervention in patients with heart failure and their caregivers: impact on caregiver outcomes. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2023;22(7):709-718. doi: 10.1093/eurjcn/zvac118.

- Chen L, Xiao LD, Chamberlain D. Exploring the shared experiences of people with stroke and caregivers in preparedness to manage post-discharge care: a hermeneutic study. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(9):2983–2999. doi:10.1111/jan.15275.

- Moss J, Roberts MB, Shea L, et al. Healthcare provider compassion is associated with lower PTSD symptoms among patients with life-threatening medical emergencies: a prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(6):815–822. doi:10.1007/s00134-019-05601-5.

- Heim E, Karatzias T, Maercker A. Cultural concepts of distress and complex PTSD: future directions for research and treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2022;93:102143. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102143.

- Broadbent E, Schoones JW, Tiemensma J, et al. A systematic review of patients’ drawing of illness: implications for research using the common sense model. Health Psychol Rev. 2019;13(4):406–426. doi:10.1080/17437199.2018.1558088.

- Jennings CS, Astin F, Prescott E, et al. Illness perceptions and health literacy are strongly associated with health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression in patients with coronary heart disease: results from the EUROASPIRE V cross-sectional survey. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2023; 22(7):719-729. doi: 10.1093/eurjcn/zvac105.

- Magnani JW, Mujahid MS, Aronow HD, et al. Health literacy and cardiovascular disease: fundamental relevance to primary and secondary prevention: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation. 2018;138(2):e48–e74. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000579.

- Santiago de Araujo Pio C, et al. Interventions to promote patient utilisation of cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2(2): p):CD007131.

- Bohplian S, Bronas UG. Motivational strategies and concepts to increase participation and adherence in cardiac rehabilitation: an INTEGRATIVE REVIEW. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2022;42(2):75–83. doi:10.1097/HCR.0000000000000639.

- Linzer M, Rogers EA, Eton DT. Reducing the burden of treatment: addressing how our patients feel about what We ask of them: a "less is more" perspective. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(5):826–829. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.01.014.

- Forsyth F, Blakeman T, Burt J, et al. Cumulative complexity: a qualitative analysis of patients’ experiences of living with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2023;22(5):529–536. doi:10.1093/eurjcn/zvac081.

- Alam MZ, Hoque MR, Hu W, et al. Factors influencing the adoption of mHealth services in a developing country: a patient-centric study. Int J Inf Manage. 2020;50:128–143. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.04.016.

- Farley H. Promoting self-efficacy in patients with chronic disease beyond traditional education: a literature review. Nurs Open. 2020;7(1):30–41. doi:10.1002/nop2.382.

- van de Bovenkamp HM, Dwarswaard J. The complexity of shaping self-management in daily practice. Health Expect. 2017;20(5):952–960. doi:10.1111/hex.12536.

- Dorje T, Zhao G, Tso K, et al. Smartphone and social media-based cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention in China (SMART-CR/SP): a parallel-group, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Digit Health. 2019;1(7):e363–e374. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30151-7.

- Brewer LC, Abraham H, Kaihoi B, et al. A community-Informed virtual world-based cardiac rehabilitation program as an extension of Center-Based cardiac rehabilitation: mixed-methods analysis of a multicenter pilot study. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2022;43(1):22–30. doi:10.1097/HCR.0000000000000705.

- Dalal HM, Doherty P, Taylor RS. Cardiac rehabilitation. BMJ. 2015;351:h5000. doi:10.1136/bmj.h5000.

- Clemensen J, et al. Telemedical teamwork between home and hospital: a synergetic triangle emerges. in 3rd International Conference on Information Technology in Health Care. Sydney, Australia.

- Ski CF, Cartledge S, Foldager D, et al. Integrated care in cardiovascular disease: a statement of the association of cardiovascular nursing and allied professions of the European society of cardiology. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2023;22(5):e39-e46. doi: 10.1093/eurjcn/zvad009.