Abstract

Background

Real-world data on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) are scarce and studies have been restricted in terms of instruments used for assessments.

Objective

To assess generic and dermatology-specific HRQoL of patients with GPP compared with patients with plaque psoriasis using real-world data from the Swedish National Register for Systemic Treatment of Psoriasis.

Methods

Cross-sectional data from 2006 to 2021 including 7041 individuals with plaque psoriasis without GPP and 80 patients with GPP, of which 19% also had plaque psoriasis. Total scores for the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), as well as degree of severity within the instruments’ dimensions/questions, were compared between patient groups.

Results

EQ-5D scores were significantly (p < .01) lower (worse) in patients with GPP (mean [standard deviation (SD)] 0.613 [0.346]) vs. patients with plaque psoriasis (mean [SD] 0.715 [0.274]), indicating lower generic HRQoL of patients with GPP. Significantly (p < .01) higher (worse) total DLQI scores were observed for patients with GPP (mean [SD] 10.6 [8.9]) compared with patients with plaque psoriasis (mean [SD] 7.7 [7.1]), with proportionally more patients with GPP having severe (20% vs. 16%) and very severe (17% vs. 8%) problems. The worsened scores for GPP vs. plaque psoriasis were consistent across EQ-5D dimensions and DLQI questions.

Conclusions

Individuals with GPP have a considerable impairment in both generic and dermatology-specific HRQoL. The HRQoL was significantly worse in individuals with GPP compared to individuals with plaque psoriasis. The significant HRQoL impairment of GPP shows the potential value of better healthcare interventions for this multisystem disease.

KEY MESSAGES

The study assessed health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) compared to patients with plaque psoriasis using real-world data from the Swedish National Register for Systemic Treatment of Psoriasis.

The results showed significantly worse HRQoL scores by two different HRQoL instruments (EuroQol-5 Dimensions [EQ-5D] and Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI]) in patients with GPP compared to patients with plaque psoriasis.

The study indicates that individuals with GPP have a considerable impairment in both generic and dermatology-specific HRQoL.

Introduction

Pustular psoriasis is a heterogeneous group of inflammatory skin disorders characterized by the presence of pustules. Pustular psoriasis is clinically, histologically and genetically distinct from the more common plaque psoriasis [Citation1].

The most severe type of pustular psoriasis is generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) [Citation1]. The prevalence of GPP has been estimated at 0.18–18 cases per 100,000, with an annual prevalence estimated at 1.5 cases per 100,000 in Sweden [Citation2]. It has been estimated that GPP accounts for 0.6–5% of psoriasis cases [Citation2–4]. GPP occurs more frequently in females than males [Citation1,Citation2].

GPP is defined by the European Rare and Severe Psoriasis Expert Network as comprising primary, sterile, macroscopically visible pustules on non-acral skin, with or without systemic inflammation or plaque psoriasis [Citation5]. Large parts of the body can be affected by the pustules, as well as redness and scaling, frequently alongside systemic symptoms [Citation6]. The patient can become severely ill with general symptoms, including fever and severe systemic inflammation. GPP has a heterogeneous clinical course, in which it can either be relapsing (>1 episode) or persistent (>3 months) [Citation5,Citation7]. GPP is considered the most severe of all psoriatic disease variants [Citation8]; GPP typically follows a pattern of disease flares, which can be life-threatening and may require hospitalization [Citation7–9].

The severe clinical manifestations of GPP present a considerable disease burden; a disease flare can adversely affect every aspect of a patient’s life [Citation10]. GPP is a multisystem disease with extracutaneous manifestations including acute respiratory distress syndrome or cardiovascular aseptic shock [Citation8,Citation9,Citation11]; in fact, patients with GPP are more likely to experience pain, fatigue, itch, anxiety and depression than those with plaque psoriasis [Citation12–15]. Patients with GPP also face increased medication use, hospitalizations and economic burden compared with those with plaque psoriasis [Citation12,Citation14–17].

A recent systemic literature review identified 20 studies on HRQoL in patients with GPP [Citation18], of which seven related to patients with GPP and plaques psoriasis and 13 related to patients with GPP only. Most studies addressed dermatological-specific HRQoL, while few addressed general HRQoL. Studies report a substantial impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of individuals with GPP [Citation19,Citation20], also when compared with other types of psoriasis, including plaque psoriasis [Citation6,Citation9,Citation13,Citation15,Citation21]. However, real-world data on HRQoL in GPP are scarce and many existing studies are based on small cohorts with limited possibility for generalization. Also, until recently [Citation13], instruments used to measure HRQoL were the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) questionnaires [Citation9,Citation19–21]. To our knowledge, there are few [Citation13] studies using the generic EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) instrument, which is useful to estimate the quality-adjusted life-years for use in cost-effectiveness analyses [Citation22,Citation23].

A better understanding of the dermatology-specific HRQoL impairment in GPP is important from a clinical perspective, as it could improve the basis for treatment decisions. The generic HRQoL impairment is important (i) as it reflects the multisystem nature of GPP and (ii) from a payer perspective/pharmaceutical development perspective as it provides an understanding of the potential value of new healthcare interventions for the disease.

The objective of this study was to analyse generic and dermatology-specific HRQoL of patients with GPP, and to compare with plaque psoriasis, using register-based data from routine clinical practice.

Materials and methods

Data source – PsoReg

This observational study is based on cross-sectional data from the Swedish National Register for Systemic Treatment of Psoriasis (PsoReg). The register was initiated in 2006 and provides real-world data from patients diagnosed with psoriasis who are using, or about to start, systemic treatment. Local, regional and university hospitals and private clinics, as well as treatment centres managed by the patient organization PSO, are enrolled in PsoReg. Data collected reflect clinical practice, because observations occur when patients visit their physician, and no visit is protocol-driven. PsoReg is described in detail elsewhere [Citation24].

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board at Umeå University (Dnr 2010-194-31M, Dnr 2011-286-32M, Dnr 2016-126-32M). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in PsoReg. Data and consent were collected electronically.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The study applied broad inclusion criteria to reflect clinical practice. Cross-sectional data from the PsoReg register from 2006 to May 2021 were used. Analysis was based on the first observation in PsoReg for each individual. The HRQoL questionnaires and the clinical examinations were performed concurrently. Patients with a registration of GPP or plaque psoriasis in PsoReg were included. Patients with concomitant palmoplantar pustulosis, erythroderma and/or acrodermatitis continua suppurativa were excluded. Patients with GPP and a concurrent registration of plaque psoriasis were included in the GPP group.

GPP diagnoses were based on the dermatologist’s clinical examination of the patients at visits in clinical routine care. As there are no unequivocal diagnostic criteria for GPP [Citation25], the diagnoses were decided on by the dermatologists according to their own knowledge and experience.

A flowchart describes the number of patients that were excluded from analyses due to missing values.

Outcome measures

Data regarding patient characteristics included sex, age, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, psoriasis onset age >30 years, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score, smoking status (current smoker), alcohol consumption (high-risk intake as defined by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare) [Citation26], concurrent diagnosis of other types of psoriasis (psoriatic arthritis, nail psoriasis, guttate psoriasis and non-pustular palmoplantar psoriasis) and ongoing treatment (at first observation).

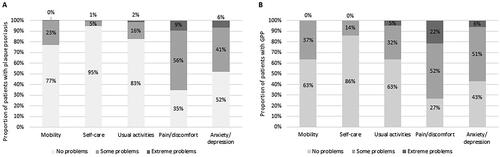

EQ-5D

The EQ-5D-Three Levels (EQ-5D-3L, hereafter only EQ-5D) is a generic standardized questionnaire that measures health status in five dimensions: ‘mobility’, ‘self-care’, ‘usual activities’, ‘pain/discomfort’ and ‘anxiety/depression’ [Citation23]. The three-level version includes three response levels: ‘no problem’, ‘moderate problem’ and ‘severe problem’. The questionnaire results in 243 health states, for which previously published utility values were attached. Utility values from the UK general population [Citation27] were used as no hypothetical values were available from the Swedish setting (only experience-based values) [Citation28]. Lower EQ-5D values reflect decreased HRQoL.

Dermatology Life Quality Index

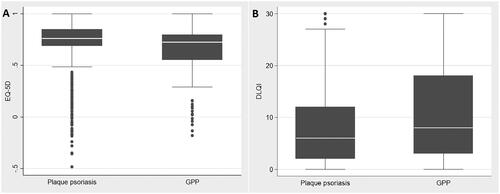

The DLQI [Citation29] is a patient-reported questionnaire of 10 questions on a four-point scale relating how the skin disease affects patients’ quality of life over the past week. The score ranges from 0 (quality of life not impaired) to 30 (quality of life severely impaired). A DLQI cumulative score of 0–1 represents no effect, 2–5 a small effect, 6–10 a moderate effect, 11–20 a very large effect and 21–30 an extremely large effect, on the patient’s life.

Analyses of HRQoL

Descriptive statistics of overall EQ-5D and DLQI scores are reported for the comparison between patients with GPP and patients with plaque psoriasis. As the PASI cut-off value for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis is PASI score ≥10 [Citation30], a subgroup analysis was performed in individuals with plaque psoriasis and a high disease severity (PASI score ≥10). A descriptive comparison (statistical significance of differences was not evaluated) of the different EQ-5D dimensions and DLQI questions was performed.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation [SD]; median, interquartile range) for patient characteristics, DLQI scores and EQ-5D scores were generated. Differences in characteristics and outcomes between groups were analysed through statistical tests as appropriate: the analysis of variance test was used for normally distributed variables, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for non-normally distributed variables and the χ2-test was used for categorical variables.

Regression analyses (ordinary least squares) were performed with EQ-5D and DLQI as the dependent variables and GPP vs. plaque psoriasis as the independent binary variable, while controlling for known determinants of HRQoL: age, sex, comorbidities (psoriatic arthritis and nail psoriasis) and lifestyle factors (BMI, smoking and high-risk alcohol consumption). Male sex, no psoriatic arthritis, no nail psoriasis, no smoker and no risk consumer of alcohol were used as reference categories. High-risk use of alcohol was defined in accordance with the recommendation issued by Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare [Citation26]. Analyses were performed both in the total plaque psoriasis cohort, as well as the subgroup plaque psoriasis and a PASI score ≥10.

Results

From a total of 10,680 patients in PsoReg, 7041 patients with plaque psoriasis (and no diagnosis of GPP) and 80 patients with GPP fulfilled the inclusion/exclusion criteria for this study (Fig. S1, see Supplementary data). Among patients with GPP, 19% (n = 15) had concomitant plaque psoriasis ().

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis and plaque psoriasis at first observation in PsoReg.

Patients with GPP were, on average, a few years older and included higher proportions of females and patients with a psoriasis onset age above 30 years, compared with patients with plaque psoriasis (). Patient groups were similar with respect to the proportions of patients with nail psoriasis, guttate psoriasis and non-pustular palmoplantar psoriasis. Systemic treatment with biologics was more common among patients with GPP than among those with plaque psoriasis. Patients with plaque psoriasis only had mean (SD) PASI scores of 7.86 (6.71).

HRQoL in patients with GPP compared to patients with plaque psoriasis

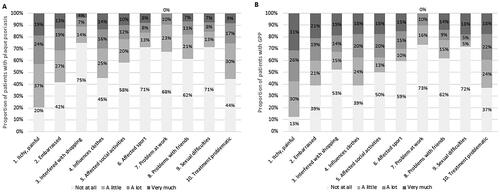

The EQ-5D score for patients with GPP (mean [SD] 0.613 [0.346]) was significantly lower (p < .01) than the score for patients with plaque psoriasis (mean [SD] 0.715 [0.274]), indicating lower HRQoL in the GPP group (; Table S1, see Supplementary data). When controlling for sex, age, comorbidities and lifestyle factors in the regression analyses, the effect size of EQ-5D was smaller but statistically significant when comparing GPP and plaque psoriasis patients; 0.036 (p < .001) (Table S2, see Supplementary data).

Figure 1. Box plots and descriptive statistics showing HRQoL by (A) EQ-5D and (B) DLQI scores in patients with plaque psoriasis or GPP. The centre line in each box represents the median; box limits represent the IQR; whiskers represent 1.5 × the IQR and black circles represent outliers. DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; EQ-5D: EuroQol-5 Dimensions; GPP: generalized pustular psoriasis; HRQoL: health-related quality of life; IQR: interquartile range.

For DLQI, patients with GPP had a significantly higher (i.e. worse) mean (SD) score (10.6 [8.9]) than patients with plaque psoriasis (mean [SD] 7.7 [7.1]; p < .01) (; Table S1, see Supplementary data). The difference in DLQI of 2.9 in the descriptive analyses was higher than the effect size of 1.4 (p < .001) observed in the regression analyses, when controlling for sex, age, comorbidities and lifestyle factors (Table S2, see Supplementary data).

Compared with plaque psoriasis, a larger proportion of patients with GPP had a DLQI score classified as a ‘Very large effect on patient’s life’ (23% vs. 20%) and, in particular, an ‘Extremely large effect on patient’s life’ (20% vs. 8%). Having ‘No effect at all’ was less common in patients with GPP (14% vs. 22%) compared to patients with plaque psoriasis ().

Figure 2. Degree of severity of total DLQI score in plaque psoriasis or GPP. DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; GPP: generalized pustular psoriasis.

About 28% of patients with plaque psoriasis had high disease severity, i.e. PASI score ≥10 (n = 1948). HRQoL in this subgroup was comparable to patients with GPP. The mean (SD) EQ-5D score in those with plaque psoriasis and a PASI score ≥10 was 0.627 (0.309) and the mean (SD) DLQI score was 11.46 (7.56). No statistically significant difference in EQ-5D nor DLQI scores was detected in patients with GPP compared with those with plaque psoriasis and a PASI score ≥10 (p = .742 and p = .116, respectively).

The results were similar when analysing females and males separately (Table S1, see Supporting Information). Mean EQ-5D and DLQI were consistently worse in patients with GPP than in those with plaque psoriasis in both sex groups (although not all statistically significant). However, the difference was more pronounced in the male groups. The median EQ-5D and DLQI scores were the same for both female patient groups.

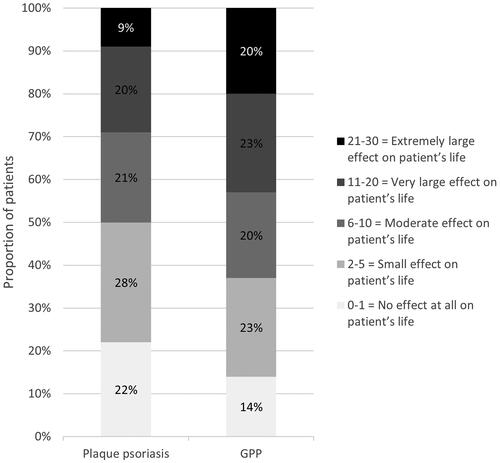

HRQoL dimensions/questions

For the EQ-5D, problems related to ‘pain/discomfort’ and ‘anxiety/depression’ were most commonly experienced by both patient groups (). Compared with plaque psoriasis, problems in all dimensions of the EQ-5D were more frequently experienced, and were more pronounced, in the GPP group.

Figure 3. Proportion of patients with (A) plaque psoriasis or (B) GPP with each response level for the five dimensions of the EQ-5D. EQ-5D: EuroQol-5 Dimensions; GPP: generalized pustular psoriasis.

In each DLQI question, a greater proportion of patients with GPP compared with those with plaque psoriasis reported that their skin affected their HRQoL (). The two problems affecting the skin the most for both GPP and plaque psoriasis groups were relating to ‘itchy, painful’ (87% and 80%, respectively) and ‘treatment problematic’ (63% and 66%, respectively).

Discussion

This observational study demonstrates that GPP has a considerable impact on both patients’ generic and dermatology-specific HRQoL. HRQoL was significantly lower in patients with GPP compared with patients who had plaque psoriasis only, both in the initial analysis and when controlling for the confounding factors age, sex, psoriatic arthritis and nail psoriasis. In fact, the HRQoL of patients with GPP was comparable to patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (PASI score ≥10).

Patients with GPP reported more problems in all EQ-5D dimensions and DLQI questions compared with patients with plaque psoriasis. A noteworthy finding is the particularly large proportions of patients in both groups reporting problems in the DLQI questions ‘Over the last week, how itchy, sore, painful or stinging has your skin been?’ and ‘Over the last week, how much of a problem has the treatment for your skin been, for example by making your home messy, or by taking up time?’

A strength of this research is that HRQoL was analysed using GPP patient data from Swedish clinical practice. Moreover, access to the national register PsoReg enabled comparison of HRQoL with a cohort of patients that had plaque psoriasis only. Nevertheless, comparisons of outcomes in observational research come with limitations due to confounding factors, especially as both age and sex are known determinants of HRQoL [Citation28,Citation31]. This was considered in the multiple regression analyses, which control for major determinants of HRQoL; age, sex, psoriatic comorbidities and lifestyle factors. The effect sizes were smaller in regression analyses, nonetheless still statistically significant. However, other factors such as socioeconomic status and other comorbidities could confound the outcomes and results should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Another limitation of this study is that, although GPP is a condition that presents with flares, there is no information in PsoReg regarding the course of the disease and whether there was an ongoing flare or not at the time of the assessment. The magnitude of impairment of HRQoL in this study could thus be an underestimation of the HRQoL impairment during flares. However, the estimates could be an overestimation of the overall HRQoL impairment of the chronic disease, as patients may visit their physicians when they are more severely ill.

The findings presented here are consistent with a recent study in patients with GPP (n = 60) or plaque psoriasis (n = 4894) from a US register, which reported mean (SD) DLQI scores of 7.8 (6.8) and 6.5 (6.1) with GPP and plaque psoriasis, respectively [Citation13]. The study also reported EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS) scores (from 0 [worst imaginable health] to 100 [best imaginable health]); mean (SD) EQ-VAS scores were 63.4 (23.8) in patients with GPP and 73.9 (20.9) in patients with plaque psoriasis [Citation13], which followed a similar pattern to the present study. However, direct comparisons between the two studies cannot be made due to differences in study populations and methodologies.

Beyond the above study, there are very limited data on HRQoL of patients with GPP that can be compared with the findings from this study. Choon et al. reported a mean (range) DLQI score of 12.4 (1–28) during a non-flare period in 95 patients with acute GPP in Malaysia, indicating severe disease [Citation9].

A recent study from Japan analysed HRQoL by the SF-36 and compared past (from 2003 to 2007) and present (from 2016 to 2019) cohorts of patients with GPP. Their results indicated an improvement in HRQoL measured by the SF-36 and the authors concluded that advances in treatment may have contributed to this improvement [Citation20].

Due to the limited number of studies assessing DLQI in patients with GPP, there is no minimal clinically important difference (MCID) defined for GPP specifically. However, for patients with inflammatory skin diseases, a score of 4 has been recommended as the MCID [Citation32] and a 2.2- to 7.0-point difference has previously been suggested in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis [Citation33,Citation34]. The higher mean DLQI score of 2.9 observed for GPP compared with plaque psoriasis may suggest a meaningful difference, but the comparison may be limited by discrepancies in patient populations.

The overall HRQoL, as measured by the EQ-5D, in the GPP patient group in our study is considerably lower (0.61) than values reported from the defined general Swedish population (0.84), although not controlling for sex, age and different clinical settings. Akin to observations in the present study, females in the general population had a significantly lower EQ-5D index value than males, of 0.83 and 0.86, respectively (compared with 0.61 and 0.63 in our study, respectively) [Citation28].

Due to the rarity of the GPP condition, a large time period was needed (2006–2021) to allow for a sufficiently large sample size in these analyses. A limitation of this approach is the generalizability of the results to reflect current clinical practice, as disease awareness and disease management may have changed over time. Even though a considerable proportion of patients with GPP had previously used biologics, there are almost no treatments directly targeted for this patient population. Of note, in the present study, more patients with GPP reported a high degree of treatment problems compared with those with plaque psoriasis This reflects the recognition among dermatology experts that new and more effective treatment options for GPP are needed [Citation7,Citation10,Citation25].

Conclusions

In conclusion, our data show that GPP has a considerable impact on patients’ HRQoL and provide a better understanding of the problems patients with GPP face in their daily lives.

Author contributions

J.M.N., S.L. and M.S.E. were involved in the conception and design of the study; J.M.N. carried out the statistical analyses. J.M.N., S.L. and M.S.E. performed analysis and data interpretation; J.M.N. drafted the manuscript; all authors revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content and approved of the version to be published; and that all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board at Umeå University, Sweden (Dnr 2010-194-31M, Dnr 2011-286-32M, Dnr 2016-126-32M). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in PsoReg. Data and consent were collected electronically.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (78.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Gunnar Brådvik and Kristoffer Nilsson, Data Analysts, for data management contributions, and Karin Wahlberg, Medical Writer, for writing and editorial support. All were employed at The Swedish Institute for Health Economics. Kate Silverthorne (OPEN Health Communications, London, UK) provided additional writing, editorial and formatting support, which was contracted and funded by Boehringer Ingelheim.

Disclosure statement

M.S.-E. is responsible for dermatology in the project management of the national guidelines for psoriasis at the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. J.M.N. and S.L. have been involved in the health economics analyses of the national guidelines for psoriasis at the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. The authors have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study were retrieved from PsoReg. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data under Swedish and European law, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Twelves S, Mostafa A, Dand N, et al. Clinical and genetic differences between pustular psoriasis subtypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(3):1021–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.06.038.

- Löfvendahl S, Norlin JM, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Prevalence and incidence of generalized pustular psoriasis in Sweden: a population-based register study. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186(6):970–976. doi: 10.1111/bjd.20966.

- Ito T, Takahashi H, Kawada A, et al. Epidemiological survey from 2009 to 2012 of psoriatic patients in Japanese Society for Psoriasis Research. J Dermatol. 2018;45(3):293–301. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14105.

- Duarte GV, Esteves de Carvalho AV, Romiti R, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis in Brazil: a public claims database study. JAAD Int. 2022;6:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2021.12.001.

- Navarini AA, Burden AD, Capon F, et al. European consensus statement on phenotypes of pustular psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(11):1792–1799. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14386.

- Kharawala S, Golembesky AK, Bohn RL, et al. The clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of generalized pustular psoriasis: a structured review. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16(3):239–252. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1708193.

- Menter A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S. Pustular psoriasis: a narrative review of recent developments in pathophysiology and therapeutic options. Dermatol Ther. 2021;11(6):1917–1929. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00612-x.

- Bachelez H. Pustular psoriasis: the dawn of a new era. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(3):adv00034.

- Choon SE, Lai NM, Mohammad NA, et al. Clinical profile, morbidity, and outcome of adult-onset generalized pustular psoriasis: analysis of 102 cases seen in a tertiary hospital in Johor, Malaysia. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(6):676–684. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12070.

- Gooderham MJ, Van Voorhees AS, Lebwohl MG. An update on generalized pustular psoriasis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15(9):907–919. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1648209.

- Lofvendahl S, Norlin JM, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Comorbidities in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis – a nationwide population-based register study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;88(3):736–738.

- Okubo Y, Kotowsky N, Gao R, et al. Clinical characteristics and health-care resource utilization in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis using real-world evidence from the Japanese Medical Data Center Database. J Dermatol. 2021;48(11):1675–1687. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16084.

- Lebwohl M, Medeiros RA, Mackey RH, et al. The disease burden of generalized pustular psoriasis: real-world evidence from CorEvitas’ Psoriasis Registry. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2022;7(2):71–78. doi: 10.1177/24755303221079814.

- Kotowsky N, Garry EM, Valdecantos WC, et al., editors. Characteristics of generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) patients: results from the Optum® Clinformatics™ Data Mart Database. In: The Annual Rare Diseases and Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit of the National Organization for Rare Disorders; 2020 Oct 8–9; 2020 NORD Annual Meeting, Washington, DC.

- Strober B, Kotowsky N, Medeiros RA, et al., editors. Patient-reported outcomes from a large, North American-based cohort highlight a greater disease burden for generalized pustular psoriasis versus plaque psoriasis: real-world evidence from the Corrona Psoriasis Registry. In: American Academy of Dermatology Virtual Meeting Experience; 2021 Apr 23–25; Virtual Meeting.

- Morita A, Kotowsky N, Gao R, et al. Patient characteristics and burden of disease in Japanese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: results from the Medical Data Vision Claims Database. J Dermatol. 2021;48(10):1463–1473. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16022.

- Löfvendahl S, Norlin JM, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Economic burden of generalized pustular psoriasis in Sweden: a population-based register study. Psoriasis. 2022;12:89–98. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S359011.

- Choon SE, De La Cruz C, Wolf P, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;38(2):265–280. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19530.

- Bachelez H, Choon SE, Marrakchi S, et al. Trial of spesolimab for generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(26):2431–2440. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2111563.

- Hayama K, Fujita H, Iwatsuki K, et al. Improved quality of life of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis in Japan: a cross-sectional survey. J Dermatol. 2021;48(2):203–206. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15657.

- Sampogna F, Tabolli S, Söderfeldt B, et al. Measuring quality of life of patients with different clinical types of psoriasis using the SF-36. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154(5):844–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07071.x.

- Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

- EuroQoL. EQ-5D; 2022 [cited 2022 Jun 21]. Available from: https://euroqol.org/

- Schmitt-Egenolf M. PsoReg – the Swedish Registry for Systemic Psoriasis Treatment. The registry’s design and objectives. Dermatology. 2007;214(2):112–117. doi: 10.1159/000098568.

- Reich K, Augustin M, Gerdes S, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: overview of the status quo and results of a panel discussion. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2022;20(6):753–771. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14764.

- Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. Rådgivande samtal om alkohol [Advisory conversation on alcohol]; 2015. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2015-1-8.pdf2015

- Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care. 1997;35(11):1095–1108. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199711000-00002.

- Burström K, Sun S, Gerdtham UG, et al. Swedish experience-based value sets for EQ-5D health states. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(2):431–442. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0496-4.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) – a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x.

- Augustin M, Langenbruch A, Gutknecht M, et al. Definition of psoriasis severity in routine clinical care: current guidelines fail to capture the complexity of long-term psoriasis management. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(6):1385–1391. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17128.

- Norlin JM, Steen Carlsson K, Persson U, et al. Analysis of three outcome measures in moderate to severe psoriasis: a registry-based study of 2450 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(4):797–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10778.x.

- Basra MK, Salek MS, Camilleri L, et al. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology. 2015;230(1):27–33. doi: 10.1159/000365390.

- Basra MK, Fenech R, Gatt RM, et al. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994–2007: a comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(5):997–1035.

- Shikiar R, Willian MK, Okun MM, et al. The validity and responsiveness of three quality of life measures in the assessment of psoriasis patients: results of a phase II study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4(1):71. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-71.