ABSTRACT

Cape Town’s water injustices are entrenched by the mismatch between government interventions and the lived realities in many informal settlements and other low-income areas. This transdisciplinary study draws on over 300 stories from such communities, showing overwhelming frustration with the municipality’s inability to address leaking pipes, faulty bills and poor sanitation. Cape Town’s interventions typically rely on technical solutions that tend to ignore or even exacerbate the complex social problems on the ground. Water justice requires attention be paid to the range of everyday realities that exist in the spectrum from formal to informal settlements.

Introduction

Freshwater scarcity is becoming an increasingly urgent problem across the planet, particularly in cities (McDonald et al., Citation2014; Mekonnen & Hoekstra, Citation2016). By 2050, rapid urbanization paired with climate change is expected to increase the number of city dwellers facing perennial water shortage by almost 1 billion in developing countries alone (McDonald et al., Citation2011). Most urban growth is expected in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, where lessons from cities in the Global North do not necessarily apply (Fragkias et al., Citation2013; Nagendra et al., Citation2018). In Cape Town, South Africa, a recent drought threatened the water supply of 4 million residents, many of whom live in the city’s sprawling informal settlements where access to water services is much more unreliable than in more affluent areas (Enqvist & Ziervogel, Citation2019; Mahlanza et al., Citation2016). Informality, however, is not simply an exception or opposite to a state-led technological service delivery ideal; rather, it is a product of a particular form of urbanization that includes informal practices (Kooy, Citation2014). Given the heterogeneity of emerging urban landscapes and the range of ways in which city dwellers depend on water, achieving water justice in cities such as Cape Town requires interventions that can grasp and adapt to the complex realities on the ground (Kooy, Citation2014; Nagendra et al., Citation2018; Ziervogel, Citation2019a).

A grounded understanding of everyday water challenges requires reliable data on people’s living conditions. This can be difficult to obtain, especially in rapidly growing cities in the south. In Malawi, official statistics claim that 96% of the urban population has access to treated water, surpassing the country’s Millennium Development Goals (WHO & UNICEF, Citation2015). However, this fails to recognize that households’ primary water sources are often unreliable (due to poorly run ‘water kiosks’ or intermittent supply) and that secondary sources are much likelier to be untreated (Adams, Citation2018). As shown by Zawahri et al. (Citation2011), many countries in northern Africa and the Middle East have similar problems, with official Development Goals statistics relying on oversimplified measures. For example, access to a tap is assumed to mean access to safe drinking water, but in fact ‘tap water is often contaminated by existing systems of treatment, distribution and storage. […] Provision of safe sanitation and potable water is particularly lacking in densely populated “informal” settlements in both rural and urban areas’ (Zawahri et al., Citation2011, p. 1172). While international development efforts are well intended, their need for harmonized data for cross-country comparisons, paired with national governments’ desire to show progress, tends to generate assessments that ignore local and contextual factors – leaving the often particularly vulnerable residents of informal settlements out of the picture (Adams, Citation2018; Zawahri et al., Citation2011).

One way to help adapt interventions to the specific conditions of each place is by drawing on pre-existing initiatives that are run at a local level. Over the past decades, water service delivery in informal settlements has seen a shift in public policy discourses away from ‘state-led initiatives to increasingly market-based, private-sector-oriented and communitarian solutions’ (Dagdeviren & Robertson, Citation2011, p. 492). Community-based initiatives typically engage local residents in partnerships with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) for technical and financial support. Studies from cities in Ghana and Malawi, for instance, have shown that involving residents from local informal settlements in local governance can promote water justice by making water services cheaper and more reliable (Adams & Zulu, Citation2015; Harris & Morinville, Citation2013). Under ideal conditions, participation in water and sanitation governance is said to help promote legitimacy, public awareness, local empowerment, accountability and sustainability (Jiménez et al., Citation2019); however, approaches relying on bottom-up engagement have their limits and should not be treated as a panacea (Enqvist & Ziervogel, Citation2020; Morinville & Harris, Citation2014; Ziervogel et al., Citation2019). Lessons from Mexico City show that although residents in informal settlements have more limited access to water services compared with others, they are still less likely to express their grievances to the government through formal or informal channels. Eakin et al. (Citation2020) argue that these residents have low expectations that public agencies will address their problems, and are therefore more likely to try to adapt or simply do nothing at all, compared with their neighbours in wealthier neighbourhoods. Often challenges to public participation in water governance involve such socio-institutional barriers rather than technical ones. Other obstacles include low public awareness of participatory processes, limited local support for or capacity to engage in them, and difficulty identifying shared visions that residents can agree on (Brown & Farrelly, Citation2009; Harris & Morinville, Citation2013). The sheer size of urban water infrastructure, and the scale at which it operates, is difficult to match by local groups’ limited capacity – not least because large coalitions among cities’ heterogeneous populations tend to require more complex negotiations and partnerships (Jiménez et al., Citation2019).

This paper uses a water justice lens that supports water democracy and citizen participation (Sultana, Citation2018), and questions whether the dominance of a neoliberal approach is able to address differential access to water services particularly for marginalized groups (Finewood & Holifield, Citation2015; Harris et al., Citation2016; Neal et al., Citation2014). In response to calls to repoliticize urban water governance (Finewood & Holifield, Citation2015; Zwarteveen & Boelens, Citation2014), the paper uses transdisciplinary methods to involve citizens not only as informants but also as partners in problem identification, research design and implementation processes, and analysis of findings. By collecting local data that reveal values and everyday stories that surface the structural inequality in urban water services, tools and strategies are generated to contest the legitimacy of technocratic responses more effectively (Finewood & Holifield, Citation2015).

Our case study includes several so-called townships and informal settlements in Cape Town. Like many South African cities, the racial discrimination dating back to Cape Town’s founding was brought to an extreme during the country’s apartheid government (1948–94), not least in terms of access to water and exposure to water-related risks such as flooding (for an overview of the city’s historical and current water woes, see Enqvist & Ziervogel, Citation2019). South Africa’s subsequent democratic government has attempted to uplift previously disadvantaged groups, but this was undermined by widespread corruption as well as efforts to promote economic growth and international competitiveness simultaneously. At a city level, increasing unemployment and higher taxes further deteriorated relationships between the City of Cape Town (‘the City’) and communities still struggling to escape poverty, indebtedness and other historical disadvantages (Jaglin, Citation2004). For instance, many households incurred debts during apartheid-era protests that included a refusal to pay for municipal services deemed inadequate (Smith, Citation2004).

During the 2000s, the City implemented several measures to reduce water use, both to comply with national requirements to conserve water resources and because no space was left to construct more dams within a practical distance. This had impressive results, but came partially at a cost to the city’s most vulnerable as ‘water management devices’ (WMDs) started being installed to restrict water use in households with outstanding debt. The argument was that devices would help households detect leaks and avoid high water bills by turning off the supply once consumption surpassed the free allocation of 350 litres/day; however, many community organizations and activists came to view them as a violation of vulnerable residents’ right to water (City of Cape Town, Citation2007; Enqvist & Ziervogel, Citation2019; Mahlanza et al., Citation2016). A record-breaking three-year drought hit Cape Town in 2015–17, resulting in the threat of ‘Day Zero’ – the day when all domestic taps would be turned off. In early 2018, Day Zero was projected as fewer than 90 days away (Enqvist & Ziervogel, Citation2019; Wolski, Citation2018). Both the drought itself and authorities’ responses to it (including raised tariffs, restrictions on water use, ramped-up WMD installations and public information campaigns) brought many pre-existing fears and frustrations to the fore, even though Day Zero was eventually avoided (Matikinca et al., Citation2020; Robins, Citation2019; Ziervogel, Citation2019a). For many residents in middle- and high-income areas, the experience became a stark reminder of the disruptions that people (of colour, predominantly) in informal settlements have suffered for decades: water cut-offs, queueing at communal taps, and risks to sanitation and personal safety.

This paper complements the dominant narrative of ‘the Day Zero drought’ as a threatening crisis, with one describing the water emergencies that already plague many of Cape Town’s residents. We seek to identify, amplify and understand some voices of Capetonians who are among the most vulnerable and exposed to water injustice. Given the challenge of studying a multidimensional problem with no one clear solution, we opted for a transdisciplinary approach that can connect diverse knowledge holders and practitioners (Knapp et al., Citation2019). This implies working collaboratively across both the boundaries between academic disciplines, as well as those between academic knowledge and the tacit and experiential knowledge held by all people (Lang et al., Citation2012; Polk, Citation2015; van Breda & Swilling, Citation2018). This mission emerged from a partnership between (1) the Western Cape Water Caucus (WCWC – ‘the Water Caucus’ or simply ‘the Caucus’), a volunteer-based water rights group with members from various low-income areas in Cape Town; and (2) researchers at University of Cape Town’s African Climate & Development Initiative (ACDI). With support from the Environmental Monitoring Group (EMG), a local NGO, and researchers at Stellenbosch University’s Centre for Complex Systems in Transition, a transdisciplinary research project was designed. This used a tool called Sensemaker to co-design a methodology for collecting stories about lived experiences from people in townships and informal settlements.

As described below, Sensemaker invites respondents to interpret and give meaning to the stories they share. This paper places a particular emphasis on describing the method and reporting on the findings, with a relatively light emphasis on researchers’ interpretations. Our discussion and conclusions focus on the implications of the findings and the methodology for water justice in urban low-income communities, including the role of participatory research and problem assessments.

Methodology

This study is a product of a series of meetings between the Caucus and two researchers at ACDI (J.E. and G.Z.), facilitated by EMG, which had previously collaborated with both parties. The Caucus, an organization run by volunteers from several townships and informal settlements around Cape Town, has been working with local water issues for about two decades. Through the meetings, Caucus members described a frustration with not being able to influence City officials to acknowledge and address the problems that the Caucus identifies in local communities. They expressed a need to acquire better ‘evidence’ to support their arguments, as well as a desire to acquire skills to collect such evidence themselves by conducting studies. These needs fit well with the ACDI researchers’ interest in better understanding water issues in low-income areas, and in supporting community organizations working with such issues. The primary purpose of the project was therefore to co-design a knowledge-production process, and to use this process to generate new understanding of water issues in Cape Town’s low-income areas. The Sensemaker research tool (Lynam & Fletcher, Citation2015; Metelerkamp et al., Citation2019) was introduced to Caucus representatives as a way to collect data from members of their communities; and an agreement was reached to jointly design a study using this tool.

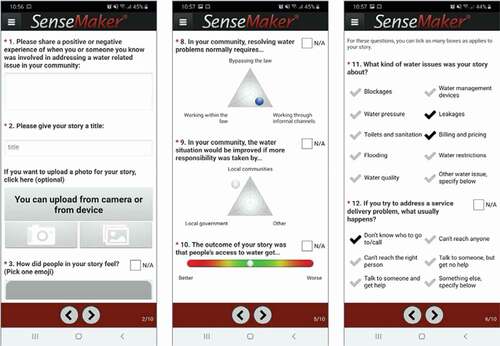

The Sensemaker approach employs a ‘signification framework’ for data collection. This consists of a prompting question to elicit stories of lived experiences, in the form of short anecdotes from respondents, followed by a series of follow-up questions to let the respondents ‘self-signify’ their stories, to clarify what they mean to them. These questions can be multiple choice, open ended or include ‘dyads’ and ‘triads’ where the respondent places a marker between two or three response options according to how they view their story (). The open-ended prompt and the follow-up questions of the signification framework allow both qualitative and quantitative information to be collected. The process can be conducted on paper or via a smartphone app, and responses are then uploaded to a software program that allows for data synthesis and visualization.

Figure 1. One option for collecting stories through the signification framework was via a smartphone-based app. The left-hand panel shows the initial prompting questions; the middle and right-hand panels show a selection of the follow-up questions asked

Study design and data collection

For our project, we needed sufficient time to co-design the signification framework and overall study approach. Two four-day workshops were organized in 2019: the first in July, to design and pilot the story collection approach; the second in October, to synthesize the collected stories and identify key insights to present back to the studied communities, City representatives, journalists and other community organizations. The workshops were facilitated by Sensemaker experts (co-authors J.B. and L.M.), assisted by representatives from EMG (T.L., A.M. and S.M.). For each workshop, the Water Caucus appointed 12 of its members to participate; seven individuals took part in both workshops and have agreed to be included as co-authors of this study (N.D., Z.M., M.M., G.N., A.O., W.R. and M.Y.) by virtue of contributing to its design, data collection and data analysis. The questionnaire, including the initial prompt and all ‘signifying’ questions, was developed jointly by the researchers and Caucus appointees during the first workshop (see Data A in the supplemental data online). The prompting question we developed was: ‘Please share a positive or negative experience of when you or someone you know was involved in addressing a water related issue in our community.’

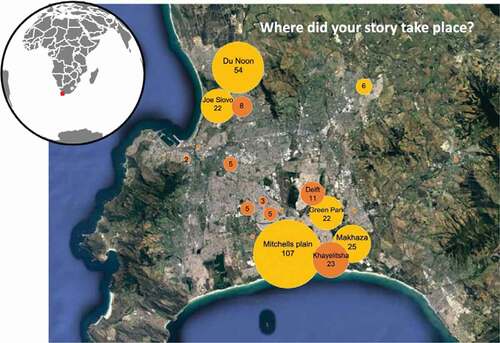

In the period between the two workshops, participants collected 311 unique stories from the areas in which they lived (Mitchells Plain, Du Noon, Makhaza, Joe Slovo, Green Park and Kraaifontein) as well as several other areas in Cape Town (). They were given the option of collecting stories on paper, or using an app version of the questionnaire adapted for smartphones. Both were made available in English, isiXhosa and Afrikaans. Stories collected on smartphones were automatically uploaded to a Sensemaker server, whereas paper-based responses were uploaded onto the server via laptops by the Caucus participants and researchers together. The researchers (J.E. and L.M.) worked to process the quantitative data to produce visual representations of the findings in posters shared with the participants.

Figure 2. Disc locations indicate where in Cape Town respondents said that their story took place, and sizes approximate the number of stories from each area. Yellow discs represent neighbourhoods where Western Cape Water Caucus (WCWC) members reside; orange discs represent other areas that respondents reported stories from.Footnote1

Data processing and analysis

During the second workshop, the Caucus participants split into three groups based on topics that the organization had previously identified as priorities: water bills, water management devices and sanitation. It should be noted that these topics were not used during story collection to prompt respondents; they were only used in the subsequent analysis for the purpose of linking the findings to the Caucus’ earlier work – and because the topics aligned very well with the collected material. Each of the three groups then read through the collected stories and identified all those that concerned their topic. Based on this, they then prepared oral presentations that would tell a common or important story to the audience – typically, this took the form of a short skit where participants role-played, for example, a troubled citizen, a City representative and an investigative news reporter. With the help of the researchers, relevant quantitative findings were identified so that the posters could also be used in the presentations to give support to the narratives. The presentations were used during three ‘story return sessions’ in the weeks after the second workshop, where the Caucus invited members of the studied communities to hear about and share their reflections on the results of the study. This step thereby also acted as a way to embed the interpretation and framing of the findings in the context that had been studied.

The study was approved by the Faculty of Science Research Ethics Committee at the University of Cape Town (approval number FSREC 99-2019). As the data were collected and are owned by the Water Caucus, the committee agreed that verbal consent was sufficient. Each respondent was given verbal information about the study by a story collector from their community, and a written version (see Data A in the supplemental data online) in English, isiXhosa or Afrikaans. The final data set was anonymized to avoid identification of any respondents or other individuals featuring in the stories. A data-use policy was developed by ACDI researchers, EMG and Caucus members to clarify what the data can be used for, and who can get access to what parts of it. This was done seeking a balance between the need to safeguard the Caucus’ interests, allow for research and sharing the study findings with the general public (for more information, see ACDI, Citation2020).

Reflections on the study process

Transdisciplinary research is characterized by knowledge co-production across academic disciplines (interdisciplinarity) as well as involving non-academic societal actors, and by facilitating outcomes including action, problem management and capacity-building (Knapp et al., Citation2019). The need for context-specific approaches, informed both by literature as well as the dynamics of research in practice, can make this work both difficult and ‘messy’ compared with more conventional research (van Breda & Swilling, Citation2018). However, it also makes collaboration and sharing of experiences within the transdisciplinary research community particularly important (Lang et al., Citation2012). We knew from the outset that we would wrestle with different ways of understanding the world, and varying levels of experience and familiarity with research procedure and ethical conduct in the academic sense. There are inherent power dynamics in any such process, not least in the context of a society still dealing with the legacy of state-led discrimination of selected parts of the population. Understanding these dynamics is key for ensuring equitable outcomes, and therefore particularly important in projects that focus on action for societal change (Knapp et al., Citation2019). In our case, the Caucus members held essential experiential knowledge of their local contexts, and the academics held more knowledge about how to access, interpret and use the collected data. There was also a transfer of knowledge through the training of the story collectors in the research method, the importance of allowing respondents to tell their own stories without being influenced or coerced, and of encouraging and collecting stories also from people who might have different opinions and perspectives than those shared by WCWC members. This was an important part of meeting the Caucus’ request for learning how to conduct research. Participants were also given information about and authority to object to the project as a whole as well as to question or oppose different steps along the way. Further, the project also recognized that their expertise was also critical for the research design itself. Since they live in the study areas and are already active community members and activists, their familiarity with the nature of the problems being studied as well as the social norms around appropriate behaviour and conduct, is more contextually rich compared with that of the academics’. A key task in this transdisciplinary research process was therefore to navigate the different power and knowledge asymmetries that cut both ways.

A part of this challenge was to find ways to address the tension and stress that surfaced during the process. The participants’ task of independently collecting 30 stories each required both time commitment and emotional endurance, as residents shared their needs for help with urgent problems. Furthermore, technical issues such as the Sensemaker application not being compatible with certain phones, and story collectors sometimes finding it difficult to upload collected stories, put a strain on the process. The academics as well as partners at EMG put considerable effort into technical support, field visits and a ‘care day’ where various frustrations or problems were raised and addressed. Here, we had the benefit of a co-author’s previous experience with emergent research design processes (van Breda & Swilling, Citation2018), as well as an adaptable time plan and sufficient budget to accommodate added activities as the need arose. These factors turned out to be critical for ensuring the completion of the project. Back-up resources were also kept available in case other needs arose, for example, for additional fieldworker ‘care days’ and other assistance in the field or for vernacular translation.

Results

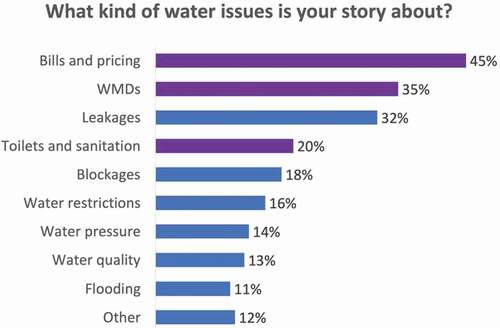

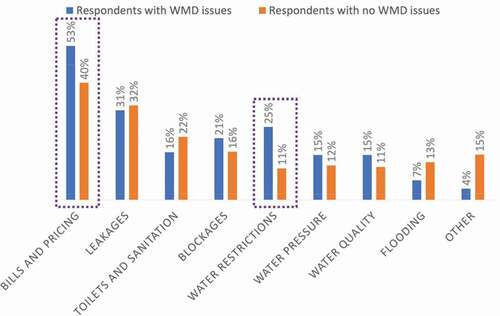

The findings show that respondents’ stories are mostly about water bills and pricing, WMDs, and water leaks; it is also clear that the three issues that Caucus members have chosen to focus their work on are also common in the stories (). Furthermore, given Cape Town’s recent water crisis, it is worth noting that only about one in six stories are about water restrictions or water pressure issues. This suggests that the impact of the drought was of limited concern to respondents, compared with other more pressing problems. Below we present four themes that stand out most clearly from the data and capture a range of different experiences on the ground.

Figure 3. Most stories are about issues around bills, water management devices (WMDs) and leaks. The three issues that the Western Cape Water Caucus (WCWC) is focusing on are also all common in the collected stories (marked in purple)

Frustrations

Perhaps the most prevalent message from the 311 stories is a sense of frustration. People struggle to find answers and solutions to their problems, and sometimes have to endure the impact of this on their daily lives for years.

Story 168: Unattended water problems in our locations

I live in a communal block of flats in Langa township, I have been living there for almost ten years now. We use taps that are leaking and very rusty as they have been there for quite some time without being changed, and no one seems to care anymore. Toilets are the same, sometimes blocked. We are helped by other community members who also live there, other than that [we get] no help from the City of Cape Town officials. We sometimes wake up to empty taps – no warning, nothing whatsoever. That is our daily life. What is strange is that they do not attend to water problems [but] they say we must be water-wise. How ironic.

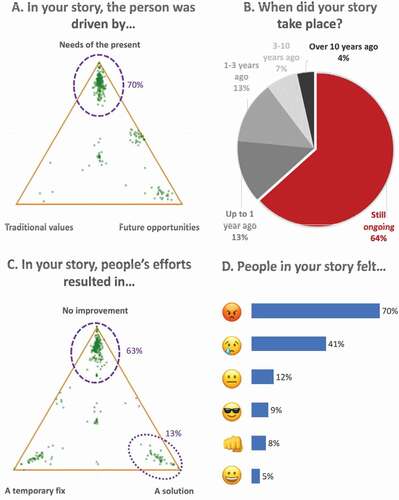

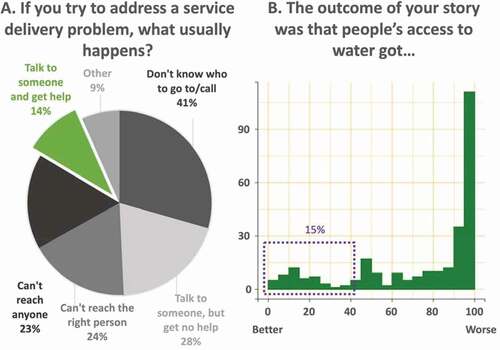

The quantitative ‘coding’ that respondents did of their own stories shows how widespread the frustrations are. Most respondents (70%) say that the people in their stories are driven by present needs rather than the past or future opportunities, and 64% of stories were coded as ‘Still ongoing’ rather than resolved (, B). Similarly, 63% of stories resulted in no improvement and, when asked about how people in their story felt, over two-thirds (70%) of respondents chose an ‘angry face’ emoji (, D). Together, this gives the impression that most residents are caught in day-to-day struggles with urgent problems that will not go away: when asked what happens when people try to address problems, the only positive option (‘Talk to someone and get help’) was the least likely choice ().

Figure 4. Roughly two-thirds of stories convey a message of frustration: people are driven by the needs of the present (196 of 282 respondents) (A), and their problems are still ongoing (197 of 306) (B); most people are unable to achieve any improvement (185 of 292) (C), and generally feel angry (215 of 307) (D). Of 292 respondents, 37 (13%) indicated that their story resulted in a solution (C)

Figure 5. Some respondents coded their stories as having some positive elements: 40 of 294 respondents (14%) usually find help when they seek it (A); and 44 of 287 respondents (15%) indicated that their story resulted in better access to water (B)

Part of the explanation for why many people experience this situation may be because of where they live: ‘Housing/planning’ is seen as the most relevant non-water issue by two-thirds respondents (rather than ‘Gardening/food growing’ or ‘Electricity’). Many respondents live in informal settlements or have limited access to resources needed for long-term solutions, which seem to trap many in unsustainable coping strategies.

Story 310: Drain leakage

My problem is a drain leaking inside my yard. My house has been built on top of a pipe, so I have to demolish my house in order to solve the problem. I went to the Housing Department and they told me that it’s not their problem. The owner is supposed to play a big role. The owner is supposed to hire a planner before extending the house. I can’t afford all of these problems – that’s why I took shortcuts.

Instead of directing frustration towards, for instance, those responsible for illegally constructing a dwelling on top of a servitude, frustration is often directed towards the City of Cape Town as the actor ultimately seen as responsible for providing housing, water and sanitation services. Many stories also describe ward councillors who are not working for their constituents, and some respondents express frustration with others in their community.

Story 29: Water leakage

I am staying in a shack-dwellers area where we are using a communal tap. Sometimes it is stolen and we use a single pipe instead. My problem is, my shack is next to the tap and there is a lot of leakage that no one cares about. We formed a committee to look at our problems, working together with the Councillor, but they are struggling to get hold of him. He is always promising to come and check our problem but till today nothing has changed. When it’s election time he is always available, asking us to help him doing door-to-door campaigns, and we honestly work with him hoping that things will be changed, but they are not. We are so frustrated because it also affects our children.

Success stories

Despite the predominant sense of frustration, a few respondents shared stories with positive outcomes. The 13% who reported that the issue in their story was resolved () is a similar proportion to the 14% that claim to usually get help when seeking it, and the 15% stating that their story resulted in better access to water (). This pattern suggests that there could be around 40–45 respondents with positive experiences.

However, on closer scrutiny, there are only 25 respondents (8% of 311) who have given ‘consistently positive’ accounts, that is, where a mostly positive story is coded to say that a solution was found, that people’s access to water improved and that the respondent usually gets help when trying to address water-related issues (see Data B in the supplemental data online). Successful problem-solving is clearly rare, but these stories also show the joy and relief respondents feel when it does happen.

Story 201: Wow to you guys (municipality)

Yesterday I woke up in the morning and found our tap’s head was gone and water was flowing out. I tried to stop the water by sticking a pipe in it. I called our municipality office and reported it. They came on the same day and fixed it by replacing [the old tap] with a new one. And I was so happy to see that they are there for our problems, and sort them out with no delays.

Understanding people’s problem-solving strategies is an important part of this project. In a closer reading of the 25 success stories, the most common reason for the resolution is help from community members (nine stories), followed by help from municipality (seven stories), self-help or hired help such as a local plumber (five stories), or unclear (four stories). With these low numbers, it is difficult to draw conclusions about broader patterns, but it is remarkable that in our sample fewer than one-third of solutions are found with help from the municipality.

Story 261: Blockages

I have a problem with a drain that [keeps] blocking, and it is in front of my front door so all the smell comes straight into the house. No one has ever come from the City of Cape Town [to do something]. I end up [relying on] people from the community to come and help even though they are not trained.

In addition to the 25 success stories, another 76 stories have some positive element in them: 21 respondents indicated that they would usually get help when they seek it (), but that this did not happen in the story they shared; seven respondents said that water access improved, but had a story that was about something else; 20 respondents shared stories of negative experiences but indicated positive outcome when answering the signifying questions – possibly due to misunderstandings or mistakes in the data collection or entry process, or a result of some stories being very short and possibly omitting positive elements that was then expressed in the follow-up questions. Lastly, 28 of the 76 stories with a somewhat positive content describe unfinished or temporary solutions, usually coded as a temporary fix by respondents (and in some cases also as having given better access to water) (), but without obtaining a satisfactory outcome.

Story 177: Platforms have made my home flood more and more

In 2017 we were relocated from a [flood-prone] wetland [area to one where they had built] platforms. It was a temporary fix, because where we are living now, on platforms, it’s flooding more than in our [old] place. We struggled a lot to build on the platform, it’s hard to dig even for a pole [due to the hardened surface], so therefore we couldn’t dig when we were building. Now we are facing a tremendous flooding [problem] because the water is going straight under our zinc sheets. While you are sitting, you’ll find water under the carpet, coming straight through from outside to inside the house. Everything gets wet in the house, and furniture gets spoiled.

Water management devices

As shown in , issues with WMDs are the second-most reported among respondents. This is remarkable given that the devices are actually an intervention from the City that is not supposed to give people problems, but rather to solve them. For many respondents, the effect seems to have been the opposite:

Story 46: Poor service

I chose a meter because I thought it would be a help, but now I regret it 'cause the water bills are higher than before. Our people are being robbed.

On closer scrutiny, it seems that the 104 respondents with WMD issues were considerably more likely to highlight problems relating to water bills and water restrictions compared with those who did not report any WMD-related issue ().

Figure 6. Stories about issues with water management devices (WMDs) are more likely also to be about water bills and restrictions, compared with stories that are not about WMDs

This finding should be interpreted carefully. Rather than indicating that all WMDs cause problems with bills and restrictions, it is more likely that if a WMD malfunctions, it is also likely to let bills skyrocket or lead to water cut-offs. However, a closer reading of the WMD-related stories reveal that many residents attribute problems to the devices, especially residents who have devices that were installed without their permission.

Story 212: Water bills

I’m very disturbed 'cause a water device was installed on my property without my consent. Now we are facing huge water bills, I don’t know where to go or who to call.

It is easy to understand that people who experience the WMD as an intrusion in their homes might become more hostile and suspicious of the government’s intentions and therefore ascribe other water problems to the device. This would mean that technology that extends the power of municipal authorities also risks increasing the number of problems that the municipal authorities are viewed as responsible for.

Citizen–state relationships

A fourth theme that also emerges through all the previous three is a breakdown of communication between local residents and municipal authorities. The frustration of residents seems rooted in a failure to reach someone who will listen to and help address people’s grievances, and the success stories are few and more likely to come from local help than the municipality. Although WMDs were intended to help residents manage high water bills and reduce leaks, they are repeatedly said to have been installed without consent and without adequate information about what they mean for the recipient. As alluded to in Story 81 below, there were also instances in which the City of Cape Town appeared to be acting against its own laws and policies, particularly with regards to debt cancelation and water billing for residents with WMDs. Many respondents expressed hopelessness, and some even doubt the City’s sincerity when it comes to improving the lot of the least privileged.

Story 81: Utterly disgusted with the City’s response

I’m so disappointed in our council that I have no trust in them. A water device was installed about a year ago. Recently I received a water bill totalling more than R16,000. Accepting the device came with an assurance that my water arrears would be scrapped. A week ago my water was cut, demanding an immediate payment of about R10,000 before reconnection. I tried unsuccessfully to engage with the council, saying I don’t have that kind of money. They promised to look into the matter. Until today, still nothing. My family is suffering.

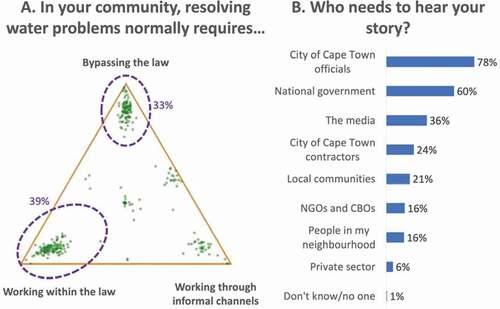

In the face of failed efforts to resolve issues through regular channels with the City of Cape Town, resorting to informal or illegal alternative solutions was common in the stories collected. Barely two of five respondents believe that water problems can normally be resolved working within the law ().

Figure 7. ‘Working within the law’ is something only 39% of respondents (111 of 287) think is required to resolve water-related problems. Most see a need for other approaches, and one-third of all respondents believe that solutions require bypassing the law (a). Most respondents want the municipal and national government to hear their stories (b)

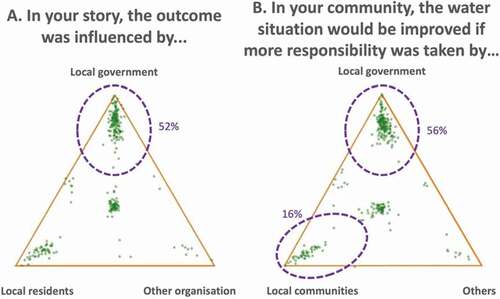

This lack of trust in the formal system is a serious threat to any efforts to work collaboratively. However, a majority of respondents indicate that the municipal government still has a role to play in addressing water-related issues. Most people want the City of Cape Town, followed by the national government, to hear their stories (). The local government is also what most people think mostly influenced the outcome of their story, and respondents believe it could improve the water situation more than local communities can ().

Figure 8. Local government was seen by most respondents as having the most influence over stories’ outcomes (146 of 279) (A) and the greatest ability to improve the water situation (165 of 296) (B). However, 48 respondents indicate that it is more important that local communities take more responsibility (B)

This suggests that there is still a wish for the government to do better. However, while just over half felt that the onus of responsibility rested squarely with the City of Cape Town, many did not share as strong a view. Of these, 16% indicated that local residents are the ones who need to take more responsibility for resolving water issues in their communities ().

Story 103: Respect the wetland

My problem is about this wetland behind us that is not fenced and no one is taking care of it. Many times we have found dead bodies, people got robbed, and stolen cars are hidden there. It’s very risky and dangerous for us and our children. People are not respecting the water, they throw their dirty stuff there, full of car tyres and clothes. I wish people could learn and know the importance of water to us as human beings and to the environment.

Some respondents also expressed a desire for ways that they can also engage and contribute:

Story 10: Platforms to engage communities

Some may be aware of [water scarcity] ’cause they have television sets and cell phones, that report almost everything happening in the surroundings. My question is: what about the people who do not have these things, and illiterate people? I think that there should be channels where the public is engaging with the City of Cape Town. They say there are platforms, but most of us do not know about them, ’cause we would like to participate, make our voices heard and make suggestions as well.

Discussion

The finding that stands out the most in this study is that two-thirds of the 311 stories describe various forms of frustration. This points to a fundamental problem in the relationship between the municipality and Cape Town’s low-income communities: residents cannot seem to find solutions to most of their water problems through formal government channels, and so many eventually start to consider it necessary to work through informal channels or even bypass the law. Fewer than one in ten respondents describe a satisfactory outcome, and when they do it is usually achieved within the local community – either by respondents themselves, by neighbours or by hiring private assistance – rather than with help from the City. Most people still think that the City of Cape Town holds the most responsibility for improving conditions, and wish that it would listen to their grievances, but only a small fraction usually find anyone to help resolve their water problems.

This problematic relationship between local communities and public agencies has been described elsewhere in terms of a lack of trust (Jaglin, Citation2004) or an absence of a ‘social contract’ (Eakin et al., Citation2020). Sometimes even benevolent efforts to improve water services can widen this gap, for instance, when interventions rely on information gathered with tools too blunt to capture the complexities of informal settlements (Adams, Citation2018; Zawahri et al., Citation2011). The City of Cape Town seeks to adopt a collaborative ‘whole-of-society’ approach to water governance, but its primary tool for understanding residents’ problems is an annual survey that merely captures quantitative information (Water and Sanitation Department, Citation2019, Citation2020). By contrast, the qualitative component of the stories that Caucus participants collected for this study provides a rich understanding of how multiple interlinked problems combine to build up frustration and a sense of abandonment among community members. When the Water Caucus presented preliminary findings to a group of City representatives during the second workshop, the latter expressed particular appreciation for insights gained from these qualitative narratives. Such opportunities to present stories and local data are important because they surface how everyday injustices are experienced, and they help to build democratic practices that are often sidelined if city-scale allocation is prioritized (Finewood & Holifield, Citation2015; Sultana, Citation2013; Zwarteveen & Boelens, Citation2014).

The WMDs provide a useful example of citizen–state tensions. This technology was introduced by the City as a tool to limit water use in non-paying households without disconnecting services entirely (City of Cape Town, Citation2007). The idea was that the devices would ensure access to a basic water supply while preventing bills running too high to be paid, detecting leaks and offering a way out of debt (Beck et al., Citation2016; Mahlanza et al., Citation2016; Yates & Harris, Citation2018). Although this was presented as a way to ‘help consumers become more responsible water users’ (Mahlanza et al., Citation2016, p. 365), WMDs are still a technological attempt to fix a social problem: it centralizes control to the City of Cape Town rather than empowering residents. These types of techno-managerial, top-down approaches are often inept at addressing injustices that are part of a complex web of issues and needs that people face on the ground (Karvonen, Citation2010; Singh, Citation2015; Ziervogel et al., Citation2017). In our study, stories describing issues with WMDs were also more likely to concern problems with bills and water restrictions (), and the respondents, rightly or wrongly, typically viewed the devices as the cause of these issues. This can be seen as an indication of unmet expectations, or a mismatch in perspectives about who is responsible for managing household water consumption and fixing leakages. For years there have been reports of WMDs being installed without giving residents adequate information about their terms of use, or without even obtaining their consent (Mahlanza et al., Citation2016). The rate of installations increased rapidly in response to the recent water crisis (Department of Water and Sanitation, Citation2018; Ziervogel, Citation2018), which might have spread more confusion about what to expect once the devices are installed.

We argue that at the core of this situation lies a failure to sustain a relationship between the City’s formal water-governance system and the informal processes that shape many low-income communities. Had WMDs been initially introduced elsewhere instead, for example, to address leaks, non-payment or indebtedness in households located in Cape Town’s formally planned suburbs,Footnote2 they might have been seen as effective and fair. This was rarely the case in the neighbourhoods in which our respondents live. The devices’ pre-set limit of 350 litres/day is sufficient to provide a basic supply for four people, but low-income households often surpass that multiple times as they tend to include extended family members as well as ‘backyard dwellers’ who rent space in a shack on the property (Mahlanza et al., Citation2016; Smith, Citation2004). Furthermore, as some of our stories show, dwellings in informal or poorly planned settlements sometimes sit on top of water mains or have illegal connections, making the question of responsibility for leaks and willingness to report them problematic. In addition, language barriers, lack of education and distrust may limit residents’ ability to safeguard their rights in terms of information and decisions about installing WMDs. Taken together, this means that an intervention that could work well under different circumstances can instead disempower people by both policing their water use and not acknowledging the reality faced in their daily lives. It thereby raises the barriers for residents to access formal service delivery: when the original problem remains unresolved or seems worsened by the ‘formal’ options offered by the City, solutions sourced within the community – sometimes illegal – easily become the norm.

This process can entrench the disconnect between the public water services and the reality people live in, and reinforce the idea that only through strict adherence to ‘formality’ does one earn the right to water services. In Mexico City, for instance, residents in poorer neighbourhoods have lower expectations of public agencies to assist them with water issues, and therefore see little reason to protest or lodge formal complaints. The lack of a ‘social contract’ contributes to a failure of communication, as people see no reason to speak up about their risk of harm from drought or flooding. Their silence leaves the municipality to instead focus resources on communities that have learnt to expect and demand more (Eakin et al., Citation2020). This breakdown in communication is an important lesson for a highly unequal and multifaceted Cape Town. The formal–informal binary is often unsuitable for such cities; instead, a more dynamic understanding of ‘emergent formalisation’ acknowledges that each context is likely to require different configurations of formal and informal elements (Misra, Citation2014). Cape Town’s new Water Strategy and Resilience Strategy hope to adopt a ‘whole-of-society’ approach with more participation and use of citizen-generated data to inform activities (City of Cape Town, Citation2019; Water and Sanitation Department, Citation2020). However, the City cannot assume that just because it opens its doors to such data, citizens will automatically provide it. When the most vulnerable residents are used to assuming that water services will not be provided for them (or that the City’s efforts are aimed at controlling their water use), the effort of articulating grievances or asking for help might easily be perceived higher than the likely reward (Eakin et al., Citation2020).

In order to improve the feedback from residents to the City, a new social contract is needed where the most vulnerable can expect and demand water services at a level equivalent to (but not necessarily identical with) wealthier residents’ expectations. This requires rebuilding trust: trust that public agencies also exist to assist residents in informal living conditions (which can exist both in areas classified as informal, and elsewhere). Low-income communities are often shaped by various degrees of informality (Kooy, Citation2014; Misra, Citation2014); and as our study shows, most people are used to informal channels being more likely to solve their problems than working through formal ones (). Water justice and more inclusive governance will benefit from building relationships that connect the formal with the informal: the lived reality of the urban poor and the structures that already exist in their neighbourhoods (Ziervogel, Citation2019b). The City therefore needs to recognize informality not simply as a problem to be addressed, or as something opposite or in absence of formal urbanity, but as something that is an inextricable part of many people’s lives and often plays a part in providing critical services (Kooy, Citation2014; Misra, Citation2014; Njiru, Citation2004).

Informality needs to be recognized not just in words but also in practical actions taken to combat water injustice. Just like this research project – a product of a transdisciplinary collaboration with internal power imbalances – inclusive governance needs to take active steps to recognize and include different types of knowledge (Grabowski et al., Citation2019). Situated knowledge that enables non-technical expertise to inform water governance is particularly important for processes aiming at bringing about transformative change and justice (Ziervogel, Citation2019b; Zwarteveen & Boelens, Citation2014). Cape Town’s ‘whole-of-society’ approach to water governance could, if done correctly, support and encourage the community-based support networks on which many residents already rely. Paired with more reliable and adaptable water services, this could start to build trust and raise people’s expectations enough to encourage a positive cycle of further collaboration with the City.

Conclusions

This paper approaches the topic of water justice through seven questions that guide this special issue. We focus on water justice concerns among residents in low-income households (1. For whom?) to any water-related issues that they perceive as urgent in their communities (2. To what?). We have chosen the context of Cape Town’s townships and informal settlements at the individual to community level (3. Where?) and focus on the current situation after the city’s recent drought (4. When?). The identified issues of injustice are largely rooted in the segregation imposed by South Africa’s apartheid policies, but also a product of the continued failure of the City of Cape Town to address the needs of a growing population of poor residents – often dependent on informal support networks, far from public amenities and exposed to environmental risk (5. Why?). A key driver of injustice that needs to be addressed is the imbalance in perspectives that impairs the City’s ability to address the problems that its residents are experiencing (6. How?); in our view, active efforts that include community voices are needed to move from tokenistic participation to more inclusive water governance (7. Which actions?). Our study demonstrates one approach for doing this in a way that empowers local communities and generates data that can be used in solutions-oriented dialogues between City officials and community organizations.

The ‘whole-of-society’ strategy adopted by the City of Cape Town in the wake of the ‘Day Zero’ drought views residents as central to shaping future water governance (Water and Sanitation Department, Citation2020). However, there is a lack of tools and mechanisms for how to form productive collaborations. The stories and information collected by local residents in this study provide a unique and new opportunity for public officials to learn about how the lived realities of residents generate both complex problems (such as water cut-offs from unpaid bills after an illegal connection started leaking) as well as seemingly simple ones (such as uncertainty about how much water a WMD allows you to use).

In order for participation to become more than words and also contribute towards water justice, municipal authorities need to acknowledge the informal structures and systems that are already in place in many neighbourhoods (Ziervogel, Citation2019b). People cannot be asked to shift away from a model that they have learnt is more dependable than the formal one, unless the alternative is designed with their perspective in mind. Importantly, this indicates that water justice cannot be achieved unless the mismatch between government interventions and people’s lived realities can be addressed. Simply giving everyone the same rights is not sufficient in an urban landscape shaped partly by informal development; water justice also needs a service delivery arrangement that is adaptable enough to acknowledge the ways in which informality both serves and constrains people’s livelihoods.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all members of the Western Cape Water Caucus (WCWC), especially those who were able to participate in this project by attending the training workshops, collecting stories or carrying out ‘story return’ events in the different communities. They are also grateful to the residents who took time to share their stories and answer questions about their situation in low-income settlements. Further, the project was made possible by meeting facilitation and logistics support from the Environmental Monitoring Group (EMG), as well as process facilitation by Jessica Wilson.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Readers of the print article can view the figures in colour online at https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2020.1841605

2. During the peak of the water crisis, the City finally decided to start installing WMDs also in high-income neighbourhoods. Efforts to curb water consumption among the highest users were effective, but created a different problem: due to the progressive tariff structure, a disproportionally high share of revenue was lost at a time when investments in new water supply were critical (Enqvist & Ziervogel, Citation2019; Visser & Brühl, Citation2018).

References

- ACDI. (2020). Community resilience in cape town (CoReCT). University of Cape Town. http://www.acdi.uct.ac.za/community-resilience-cape-town-corect

- Adams, E. A. (2018). Thirsty slums in African cities: Household water insecurity in urban informal settlements of Lilongwe, Malawi. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 34(6), 869–887. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2017.1322941

- Adams, E. A., & Zulu, L. C. (2015). Participants or customers in water governance? Community–public partnerships for peri-urban water supply. Geoforum, 65, 112–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.07.017

- Beck, T. L., Rodina, E., Luker, L., & Harris, L. (2016). Institutional and policy mapping of the water sector in South Africa. Vancouver.

- Brown, R. R., & Farrelly, M. A. (2009). Delivering sustainable urban water management: A review of the hurdles we face. Water Science and Technology, 59(5), 839–846. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2009.028

- City of Cape Town. (2007). Long-term water conservation and water demand management strategy. Page Water & Sanitation and Water Demand Management. https://resource.capetown.gov.za/documentcentre/Documents/City%20strategies%2C%20plans%20and%20frameworks/Resilience_Strategy.pdf

- City of Cape Town. (2019). Resilience strategy.

- Dagdeviren, H., & Robertson, S. A. (2011). Access to water in the slums of sub-Saharan Africa. Development Policy Review, 29(4), 485–505. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2011.00543.x

- Department of Water and Sanitation. (2018). Water outlook 2018 report, revision 24. City of Cape Town.

- Eakin, H., Shelton, R., Baeza, A., Bojórquez-Tapia, L. A., Flores, S., Parajuli, J., Grave, I., Estrada Barón, A., & Hernández, B. (2020). Expressions of collective grievance as a feedback in multi-actor adaptation to water risks in Mexico City. Regional Environmental Change, 20, 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01588-8

- Enqvist, J., & Ziervogel, G. (2019). Water governance and justice in Cape Town: An overview. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water, 6(4), e1354. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1354

- Enqvist, J., & Ziervogel, G. (2020). Multilevel governance for urban water resilience in Bengaluru and Cape Town. In R. Plummer & J. Baird (Eds.), Water resilience: Management and governance in times of change (pp. 193–211). Springer.

- Finewood, M. H., & Holifield, R. (2015). Critical approaches to urban water governance: From critique to justice, democracy, and transdisciplinary collaboration. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water, 2(2), 85–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1066

- Fragkias, M., Güneralp, B., Seto, K. C., & Goodness, J. (2013). A synthesis of global urbanization projections. In T. Elmqvist, M. Fragkias, J. Goodness, B. Güneralp, P. J. Marcotullio, R. I. McDonald, S. Parnell, M. Schewenius, M. Sendstad, K. C. Seto, & C. Wilkinson (Eds.), Urbanization, biodiversity and ecosystem services: Challenges and opportunities (pp. 409–438). Springer.

- Grabowski, Z. J., Klos, P. Z., & Monfreda, C. (2019). Enhancing urban resilience knowledge systems through experiential pluralism. Environmental Science & Policy, 96, 70–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2019.03.007

- Harris, L. M., McKenzie, S., Rodina, L., Shah, S. H., & Wilson, N. J. (2016). Water justice: Key concepts, debates and research agendas. In R. Hollifield, J. Chakraborty, & G. Walker (Eds.), Handbook of environmental justice (pp. 1–23). University of British Columbia.

- Harris, L. M., & Morinville, C. (2013). Improving participatory water governance in Accra, Ghana. CIGI-Africa Initiative Policy Brief Series.

- Jaglin, S. (2004). Water delivery and metropolitan institution building in Cape Town: The problems of urban integration. Urban Forum, 15(3), 231–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-004-0002-8

- Jiménez, A., LeDeunff, H., Giné, R., Sjödin, J., Cronk, R., Murad, S., Takane, M., & Bartram, J. (2019). The enabling environment for participation in water and sanitation: A conceptual framework. Water, 11(2), 308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/w11020308

- Karvonen, A. (2010). MetronaturalTM: Inventing and reworking urban nature in Seattle. Progress in Planning, 74(4), 153–202. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2010.07.001

- Knapp, C. N., Reid, R. S., Fernández-Giménez, M. E., Klein, J. A., & Galvin, K. A. (2019). Placing transdisciplinarity in context: A review of approaches to connect scholars, society and action. Sustainability, 11(18), 1–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184899

- Kooy, M. (2014). Developing informality: The production of Jakarta’s urban waterscape. Water Alternatives, 7(1), 35–53. http://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/volume7/v7issue1/232-a7-1-3/file

- Lang, D. J., Wiek, A., Bergmann, M., Stauffacher, M., Martens, P., Moll, P., Swilling, M., & Thomas, C. J. (2012). Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustainability Science, 7(S1), 25–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-011-0149-x

- Lynam, T., & Fletcher, C. (2015). Sensemaking: A complexity perspective. Ecology and Society, 20(1), 65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07410-200165

- Mahlanza, L., Ziervogel, G., & Scott, D. (2016). Water, rights and poverty: An environmental justice approach to analysing water management devices in Cape Town. Urban Forum.

- Matikinca, P., Ziervogel, G., & Enqvist, J. (2020). Drought response impacts on household water use practices in Cape Town, South Africa. Water Policy, 22, 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2020.169

- McDonald, R. I., Green, P., Balk, D., Fekete, B. M., Revenga, C., Todd, M., & Montgomery, M. (2011). Urban growth, climate change, and freshwater availability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(15), 6312–6317. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1011615108

- McDonald, R. I., Weber, K., Padowski, J., Flörke, M., Schneider, C., Green, P. A., Gleeson, T., Eckman, S., Lehner, B., Balk, D., Boucher, T., Grill, G., & Montgomery, M. (2014). Water on an urban planet: Urbanization and the reach of urban water infrastructure. Global Environmental Change, 27, 96–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.022

- Mekonnen, M. M., & Hoekstra, A. Y. (2016). Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Science Advances, 2(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1500323

- Metelerkamp, L., Drimie, S., Biggs, R., & Metelerkamp, L. (2019). We’re ready, the system’s not – Youth perspectives on agricultural careers in South Africa careers in South Africa. Agrekon, 58(2), 154–179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2018.1564680

- Misra, K. (2014). From formal–informal to emergent formalisation: Fluidities in the production of urban waterscapes. Water Alternatives, 7(23), 15–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2020.169

- Morinville, C., & Harris, L. M. (2014). Participation, politics, and panaceas: Exploring the possibilities and limits of participatory urban water governance in Accra, Ghana. Ecology and Society, 19(3), 36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06623-190336

- Nagendra, H., Bai, X., Brondizio, E. S., & Lwasa, S. (2018). The urban south and the predicament of global sustainability. Nature Sustainability, 1(7), 341–349. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0101-5

- Neal, M. J., Lukasiewicz, A., & Syme, G. J. (2014). Why justice matters in water governance: Some ideas for a ‘water justice framework’. Water Policy, 16(S2), 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2014.109

- Njiru, C. (2004). Utility – Small water enterprise partnerships: Serving informal urban settlements in Africa. Water Policy, 6(5), 443–452. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2004.0029

- Polk, M. (2015). Transdisciplinary co-production: Designing and testing a transdisciplinary research framework for societal problem solving. Futures, 65, 110–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2014.11.001

- Robins, S. (2019). ‘Day Zero’, hydraulic citizenship and the defence of the commons in Cape Town: A case study of the politics of water and its infrastructures (2017–2018). Journal of Southern African Studies, 45(1), 5–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2019.1552424

- Singh, N. M. (2015). Payments for ecosystem services and the gift paradigm: Sharing the burden and joy of environmental care. Ecological Economics, 117, 53–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.06.011

- Smith, L. (2004). The murky waters of the second wave of neoliberalism: Corporatization as a service delivery model in Cape Town. Geoforum, 35(3), 375–393. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2003.05.003

- Sultana, F. (2013). Gendering climate change: Geographical insights. The Professional Geographer, 66(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2013.821730

- Sultana, F. (2018). Water justice: Why it matters and how to achieve it. Water International, 43(4), 483–493. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2018.1458272

- van Breda, J., & Swilling, M. (2018). The guiding logics and principles for designing emergent transdisciplinary research processes: Learning experiences and reflections from a transdisciplinary urban case study in Enkanini informal settlement, South Africa. Sustainability Science, 14(3), 823–841. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0606-x

- Visser, M., & Brühl, J. (2018, March 1). Op-Ed: A drought-stricken Cape Town did come together to save water. Daily Maverick.

- Water and Sanitation Department. 2019. Customer perception and satisfaction survey 2017/18 results report. City of Cape Town. http://resource.capetown.gov.za/documentcentre/Documents/City%20research%20reports%20and%20review/WS_Customer_Satisfaction_Survey_Results_Report.pdf

- Water and Sanitation Department. (2020). Our shared water future: Cape Town’s water strategy. City of Cape Town. http://resource.capetown.gov.za/documentcentre/Documents/City%20strategies%2c%20plans%20and%20frameworks/Cape%20Town%20Water%20Strategy.pdf

- WHO & UNICEF. (2015). Progress on sanitation and drinking water – 2015 update and MDG assessment. UNICEF and World Health Organization. https://www.unicef.org/publications/index_82419.html

- Wolski, P. (2018). How severe is Cape Town’s ‘Day Zero’ drought? Significance, 15(2), 24–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-9713.2018.01127.x

- Yates, J. S., & Harris, L. M. (2018). Hybrid regulatory landscapes: The human right to water, variegated neoliberal water governance, and policy transfer in Cape Town, South Africa, and Accra, Ghana. World Development, 110, 75–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.021

- Zawahri, N., Sowers, J., & Weinthal, E. (2011). The politics of assessment: Water and sanitation MDGs in the middle East. Development and Change, 42(5), 1153–1178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01730.x

- Ziervogel, G. (2018). Climate adaptation and water scarcity in southern Africa. Current History May, 117(799), 181–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2018.117.799.181

- Ziervogel, G. (2019a). Building a climate resilient city: Lessons from the Cape Town drought. African Centre for Cities, University of Cape Town.

- Ziervogel, G. (2019b). Building transformative capacity for adaptation planning and implementation that works for the urban poor: Insights from South Africa. Ambio, 48(5), 494–506. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1141-9

- Ziervogel, G., Pelling, M., Cartwright, A., Chu, E., Deshpande, T., Harris, L., Hyams, K., Kaunda, J., Klaus, B., Michael, K., Pasquini, L., Pharoah, R., Rodina, L., Scott, D., & Zweig, P. (2017). Inserting rights and justice into urban resilience: A focus on everyday risk. Environment and Urbanization, 29(1), 123–138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247816686905

- Ziervogel, G., Satyal, P., Basu, R., Mensah, A., Singh, C., Hegga, S., & Abu, T. (2019). Vertical integration for climate change adaptation in the water sector: Lessons from decentralisation in Africa and India. Regional Environmental Change.

- Zwarteveen, M. Z., & Boelens, R. (2014). Defining, researching and struggling for water justice: Some conceptual building blocks for research and action. Water International, 39(2), 143–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2014.891168