ABSTRACT

This paper analyses the socio-territorial conflict prompted by Los Merinos: a residential–tourism project constructed in an ecological reserve that is vital to Andalusian livelihoods. It examines disputes concerning discourses, authorities and rules in order to understand the struggle over land and water. Using the echelons of rights analysis (ERA) framework, the paper scrutinizes the multiscale forces and strategies adopted by business and opposing movement networks in order to shape territory, thereby engaging local and supra-local governments. The authors’ political–ecology lens on environmental justice and territorialization enhances the understanding of the relevance of social movements in contesting the misappropriation of socio-natural environments.

Introduction

Spain is known throughout the world for its highly successful marketing of the promise of sun and sand. Beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, the tourist sector was framed as the motor of the ‘Spanish Economic Miracle’. The country offered a product that was in high demand among the growing working classes in other European countries – affordable vacations in a region with a pleasant climate – and tourist numbers grew exponentially during the last decades of the twentieth century. The construction sector became one of the drivers of the national economy. Operating in symbiosis, the tourism and constructions sectors sparked the rapid transformation of vast rural areas into urban areas throughout Spain, stretching beyond the coast to affect upcountry areas as well. Between 2002 and 2007, residential tourism developed as a new model materialized based on urban megaprojects. These developments created isolated, private residential leisure areas that are completely separate from the territories in which they were located (Aledo Tur, Citation2008).

This phenomenon is epitomized by Costa del Sol in the south of Spain. Private houses, hotels, resorts and golf courses have started appearing throughout the Andalusian landscape, while fertile lands and vast natural areas have been urbanized, and a considerable portion of the coastal and interior ecosystems has disappeared (Nogueira & Rico, Citation2017). The land has been prepared for the arrival of mass tourism, primarily from the UK, Germany, France and the Netherlands, as well as other locations in Spain (Observatorio Turístico de la Costa del Sol – Málaga, Citation2018). Corruption and malversation of funds have had a major influence on urban development in this area. Cases of dubious financial agreements between local governments and construction companies are abundant, as is the lack of governmental control of project implementation and a lack of enforcement of urban-development laws (Prieto Del Pino, Citation2008). One outstanding case involves the municipality of Marbella in 2006, when the mayor, the first deputy mayor and the urbanism advisor were all put in gaol, and the city council was dissolved due to urban corruption (Pérez, Citation2006).

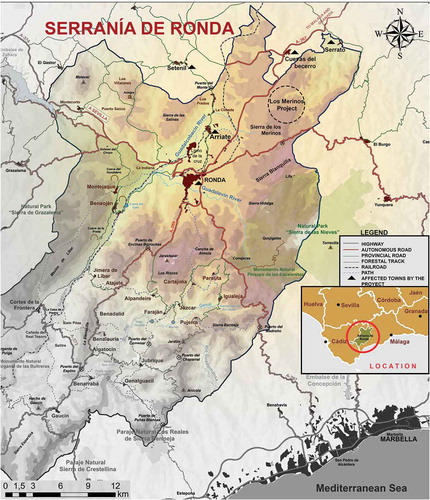

Once the Costa del Sol region became saturated with tourism projects, urban developers started projecting residential tourism projects on nearby inland areas. One example involved the Los Merinos project, located in Serranía de Ronda, Malaga (see ). This project involved the construction of a luxurious tourism complex with golf courses and 800 houses adjacent to a newly developed, fully fledged Formula 1 Grand Prix racing circuit, all within the Sierra de las Nieves Biosphere Reserve, an important protected ecological area. This reserve has a delicate hydrological balance in addition to being home to traditional Andalusian livelihood systems (Prieto, Citation2017).

Figure 1. Los Merinos project in Serranía de Ronda, located to the south of Cuevas del Becerro and to the north-east of Ronda

This paper examines the social responses and mobilization of civil society against the urban promoters to reveal contradictions and disputes that have emerged within this hydrosocial territory. Controversies involve the strongly diverging norms, authorities and discourses of actors in their attempts to defend or gain control over land and water rights within this Andalusian setting. To analyse these disputes, the theoretical lens of the ‘echelons of rights analysis’ (ERA) framework is used (Boelens, Citation2015; Zwarteveen & Boelens, Citation2014). The Los Merinos case involves the consolidation of a socio-ecological movement: the Ronda Highlands Water Defence Platform (Plataforma Serranía de Ronda para la Defensa del Agua). This grassroots movement started to mobilize the public debate and gradually acquired decision-making power, thereby contesting the powerful coalition of ‘urban development’ actors and its discourse of modernization, all with the objective of protecting territory and water rights.

This paper analyses the Los Merinos project, which illustrates the threat of land and water-grabbing through the enclosure of the commons, which is occurring throughout the world, and particularly in Spain. It explores the different strategies that business groups used to transform this hydrosocial territory into a luxurious residential–tourist area, in addition to investigating the social movement’s contestation in order to protect existing hydro-territorial rights. The paper demonstrates how a government can act as a double agent on several political scales in the midst of such social battles.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The next section describes the Los Merinos urban project in Serranía de Ronda. The third and fourth sections describe the methodology applied in this research and define the conceptual framework. The fifth section analyses the Los Merinos conflict based on the ERA framework. The sixth section presents the discussion and conclusions regarding the struggle over land and water access, its outcome and the future of Los Merinos.

A residential urban project in Serranía de Ronda: Los Merinos Norte

Francisco Franco’s dictatorial regime (1936–75) laid the foundations for the conversion of the country into one of Europe’s most important tourism destinations (Navarrete, Citation2005). Once the country’s economy opened to international trade and European visitors in the 1960s and 1970s, the tourism sector started booming. It continued to grow after the reinstallation of a democratic regime, and it now constitutes an important part of the economy. In 2007, housing construction contributed 9.3% of national gross domestic product (GDP) (Romero, Citation2010). According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization (Citation2019), Spain was the second most-visited country in the world in 2018. The rapid growth of residential tourism has had a negative impact on the country’s landscape and ecosystems, however, with effects also extending to the cultural and social cohesion of a large number of towns and cities (see also LaVanchy & Taylor, Citation2015; Sauri, Citation2019). The burgeoning tourism industry was encouraged by the 1997 Land Law, which allowed land-market liberalization (BOE (Official State Gazette), Citation1997) and transformed land into an increasingly privatized and transferable commodity, void of cultural values (cf. Achterhuis et al., Citation2010; Baud et al., Citation2019). This law encouraged the purchase of rural land at low prices for purposes of real-estate construction and resale as urban land at three times the original price. These policies and the accompanying large-scale political and financial corruption undermined the existing legal principles of integrated spatial land planning: environmental protection and sustainable water-governance norms (Prieto, Citation2017; Swyngedouw & Boelens, Citation2018).

This is the context of the Los Merinos Norte project, which was planned by Swiss capitalist investors in the 1980s. Once tourist real-estate development had saturated the space that was available for urbanization in Costa del Sol, developers started moving their housing-development projects to nearby inland areas. One attractive location was Serranía de Ronda, which is well known for its fascinating natural environment. Several projects were planned for the northern part of the municipality of Ronda. One of these projects was Los Merinos Norte, which was intended to complement the Los Merinos Sur project, which effectively constructed an entire Formula 1 Grand Prix racing circuit in the middle of this fragile ecological reserve. Los Merinos Norte comprised 785.8 hectares, with plans to construct two golf courses, an equestrian centre, 800 large villas, a luxury hotel, two schools, a sports park, commercial and social facilities, and private and public green areas. The entire urban complex was projected to accommodate a total population of 4091 people (Fraga, Citation1995). The implementation of Los Merinos Norte started 20 years after it was first conceived, when the Promociones de Club de Campo y Golf Ronda, S.L. company acquired the project.

A group of local inhabitants perceived the project as a threat to the high cultural and ecological value of the Los Merinos Norte territory. It was also perceived as a threat to the body of groundwater existing within the territory, which is an important water source at both the regional and local levels. The project infrastructure would invariably lead to the destruction of the oak forest ecosystem, and the golf course would inevitably induce profound overexploitation and pollution of the groundwater. The members of the ecologist group Silvema – Serranía de Ronda launched an awareness-raising campaign to mobilize collective action against the project. Concerned about their water supply, the mayor and a large part of the civil society of a neighbouring municipality, Cuevas del Becerro, joined the movement, forming the core of the newly constituted ‘Ronda Highlands Water Defence Platform’. Other local ecology associations and individual citizens joined as well. The ensuing conflict between this social movement and the local/international business group that was promoting the project involved legal disputes, multiscale and multi-actor alliance-building, and strategies aimed at influencing public opinion. Local and regional governments, civil groups, the media and academia took sides and influenced the evolution of the conflict.

Methodology

This article is based on a literature review and fieldwork conducted in several periods in 2016 and 2017, with follow-up work in 2018. The research was conducted within the framework of a master’s and a doctoral thesis, in cooperation with the Justicia Hídrica/Water Justice Alliance (www.justiciahidrica.org). The authors conducted 38 semi-structured interviews with four groups of actors who were actively involved in the conflict, as well as with third parties who were less directly involved. The first group of actors who were actively involved in the conflict were members of the ecologist local group of Ronda, inhabitants of Ronda and Cuevas del Becerro, and the former Mayor of Cuevas del Becerro. The second group consisted of representatives of the business group promoting the residential tourism project. The third group comprised government officials at two different levels: at the local level, the mayors of Ronda, Cuevas del Becerro, Arriate and Setenil; and at the provincial level, the former delegate of the Environment of Málaga. The fourth actively involved group consisted of local and provincial journalists who had been reporting on the development of the conflict for years. Interviewees who were not directly involved in the conflict were regional and provincial government officials and academics. Also interviewed was the chief executive officer (CEO) of the team of architects who designed and modified territorial planning. All the interviews were conducted in Spanish, the native language of the interviewers. Besides conducting the interviews, the author organized group discussions and transect walks, participated in local field observations, examined media coverage (radio, television, newspapers, videos, internet) from past and current periods, and reviewed the grey literature and legal and policy documents.

Conceptual notions: echelons of rights analysis (ERA)

Given that water is a finite resource, most contexts involving competing water uses entail appropriation by one sector, thereby implying scarcity for another. Water is thus a materially disputed resource, and any study of water justice must therefore involve analysing the distribution of water benefits and burdens – including needs, rights, obligations and privileges – across various social sectors. At the same time, however, socio-environmental justice should not be considered exclusively from the perspective of material resources or distributive justice. It is also important to consider representational justice (i.e. participation) and cultural justice (i.e. recognition) and the ways in which these forms of justice shape the political process (Fraser, Citation2000; Schlosberg, Citation2004). In addition to distributive, representational and cultural justice, Zwarteveen and Boelens (Citation2014) emphasize the importance of considering ecological justice (i.e. socio-ecological integrity) when examining water-justice struggles, arguing that this aspect is essential for sustaining ecosystems and related water-based livelihoods, both now and in the future. The intertwined nature of these spheres is demonstrated in the struggles of the Water Defence Platform, which adds substance and identity to the construction of territory and a geographical sense of belonging among Ronda dwellers (cf. Duarte-Abadía et al., Citation2019; Poma & Gravante, Citation2015). In turn, the construction of territory and belonging constitute powerful tools with which to defend hydro-territorial rights (cf. Bebbington et al., Citation2010; Boelens & Vos, Citation2014; Escobar, Citation2008, Citation2018; Jackson, Citation2018; De Vos et al., Citation2006; Wilson, Citation2019).

The construction of territory gives rise to new, rooted languages of valuation (Duarte-Abadía & Boelens, Citation2016; Martínez-Alier, Citation2002), which draw links between the ecological, political and cultural aspects (Boelens & Gelles, Citation2005; Van der Ploeg, Citation2008). These languages contest the instrumental and utilitarian valuation languages that commonly steer modernist–capitalist territorial transformations (Duarte-Abadía & Boelens, Citation2019; Schmidt & Peppard, Citation2014; Swyngedouw, Citation2015). The notion of ‘hydrosocial territories’ (Boelens et al., Citation2016) facilitates the exploration of this arena of multiple conflicting languages of valuation and the ways in which territories are transformed from contested imaginaries into materialized realities (e.g. Ricart et al., Citation2019; Rocha López et al., Citation2019). Hydrosocial territories are understood as (disputed) spatial configurations that interlink institutions, norms, technology, discourses, knowledge and financial resources with regard to the control of water. This study analyses the Los Merinos Norte project as a hydrosocial territory imagined and planned by foreign investors, supported by the local government, and confronted with the Platform’s alternative perspectives on hydrosocial territory.

To examine the conflicts over hydro-territorial configuration in Los Merinos, the theoretical framework of ERA is used (Boelens, Citation2015; Zwarteveen & Boelens, Citation2014), which identifies four echelons of conflict: (1) conflict over the distribution of and access to water (and water-related) resources; (2) conflict over the content of norms, rights and rules (that regulate the flow and distribution of resources); (3) conflict over the legitimate authority (to establish such norms, rights and rules); and (4) conflict over discourses (that subsequently defend the authority and legitimacy of rule-making and resource distribution).

The study of disputed resource access and management focuses on water and land, as well as on the infrastructure and financial/material means for the use and management of land and water. The study of contested norms, rights and rules is conditioned by legal pluralism, which has been defined as the existence and interaction of different normative orders within the same socio-political space (Roth et al., Citation2015; De Vos et al., Citation2006). Socio-environmental conflicts commonly arise between informal (e.g. customary, religious or cultural) and formal norms, or between different scales and powers (e.g. local, regional or national) involved in formal legislation. In the case of Los Merinos, different water and land laws and policies existed and were used by the actors in the conflict as legitimization tools. Conflicts over legitimacy of authority focused on conflicting decision-making powers, questioning the dominant value and institutional frameworks in resource policies and regulations, and determining which actors should have the voice and legitimacy to implement, debate or modify such policies. Formal authorities (e.g. the Mayor of Ronda or the river basin authority) have decision-making power established by law. At the same time, however, informal authorities have decision-making power due to their position, influence on social opinion, or role in creating principles and values. For example, the positive messages about the project issued by Ronda’s newspaper and radio served to steer local opinion at least partly in favour of its implementation. In addition, the existence of different modes of public–private partnerships can blur the boundaries between official authority structures, particularly when many state officials commonly continue their careers in private companies (role-rotation practices; Veldwisch et al., Citation2018; cf. Ruiz-Villaverde et al., Citation2010). The analysis of conflicting discourses focuses on how actors articulate and legitimize territorial projects, for example, by considering the ways of defining territory that were promoted (and discredited) and identifying the discursive strategies that lead one use of water and land resources to prevail over another. In addition to studying the use of language, the analysis of discourses requires examining the use of knowledge, which influences the truth regimes that prevail in any given society. Power, knowledge and truth are directly interrelated (Feindt & Oels, Citation2005; Fletcher, Citation2017; Foucault, Citation1980). For example, in Ronda, knowledge concerning the groundwater characteristics and the ecology of Los Merinos Norte land is crucial to evaluating the potential risks of a project regarding the water security of Serranía de Ronda (cf. Allan et al., Citation2015; De Stefano et al., Citation2015; Trottier et al., Citation2019).

In this case study, the struggle for the defence of water rights is based on a conflict over land use and valuation, with access to groundwater resources implying access to land. The dispute also concerns access to land, as it harbours a highly valuable ecosystem. For this reason, the ERA framework is applied to the analysis of conflict over both types of resources. The next section presents an analysis of the discourses, authorities, rules and norms of the actors in the conflict, as well as their ultimate outcome with regard to land-use planning and access to the water resources of Serranía de Ronda.

Analysing the hydrosocial territorial conflict using the ERA framework

This section examines three actors: the business group (land buyers and project promoters) represented by the company Promociones Club de Campo y Golf Ronda, S.L.; the social movement organized in the Plataforma Serranía de Ronda para la Defensa del Agua; and the government, depicted primarily by Ronda council. All these actors defended their own interests in territorial ordering – through discourses deploying diverse languages of valuation – to legitimize different forms of authority, each of which seeks to defend or promote particular rules that will ultimately determine who would have access to the territory and water of Merinos Norte.

Discourses on progress and environmental justice

The Los Merinos Norte conflict involves the fundamental competition and collision between two discourses: one on progress and one on environmental justice. The project promoters used a high-modernist discourse to justify their interests. More specifically, Promociones Club de Campo y Golf Ronda, S.L. and the Ronda government defended the project as a means to progress, defined as quick economic growth. They argued that the project would generate benefits not only for the company but also for the city and the comarca of Ronda. As expressed by the former manager of the company:

Why is there so much unemployment? […] Because there are protection zones that limit activity in the area. Ronda has problems because of very strict environmental measures. This generates unemployment, misery, frustration. […] In a city with 30% unemployment, the same unemployment rate as the Gaza Strip, you must provide economic viability, and not only prohibition, limitation, and protection. […] All cities must have business in order to operate and to create jobs. (interview, former manager of Promociones Club de Campo y Golf Ronda)

According to this discourse, the project would generate three major benefits. First, the company would provide the city council with direct access to financing through the payment of a percentage of the project’s houses that urban promoters would be obliged to allocate to the local government, which would have the option of using them, selling them independently or selling them back to the urban promoters, with the third option being the most common. This arrangement served as the major source of funding for many small municipalities in Spain from the 1960s to the breakdown of the construction sector in 2008 (Román & Rebaque, Citation2016). Romero (Citation2010) describes this type of influence of construction projects on local governments as ‘state capture’ or, more specifically, the ‘de facto colonization of local institutions and governments by business sectors and interest groups’. In Merinos Norte, the houses allocated to the local government were valued at €18 million, €15 million of which would be paid to the city council in advance.

The second benefit to be generated by the project was employment: temporary jobs during the construction phase, as well as long-term jobs for gardeners, hotel receptionists, waiters, cleaners and maintenance staff. The former company manager assured the creation of 2400 new jobs. As a final benefit, the project was to attract customers with a high level of purchasing power, which would generate economic benefits by increasing the profits of local businesses. The promoters argued that the urban tourism project would settle the population permanently. As noted by a former Mayor of Ronda:

I would like people to be able to live here and not to have to go elsewhere. […] Many people who live in Ronda have to move to the coast or to Málaga, but people would like to have jobs in their own hometown. […] I don’t understand why I can’t build in Rondathe same way that they do in Málaga city’. (interview, former Mayor of Ronda)

Arguments of distributive justice, as expressed in terms of employment opportunities, were central to the discourse of the project promoters. The former manager of the company promoted the project as a factory that would provide employment for local people: ‘Ronda could be one of the cities with the lowest unemployment rate and most economic resources in the whole region.’ The local newspaper and radio spread the same message: ‘If we have decided to live from tourism, let’s live from tourism. And golf course tourism is of crucial importance’ (interview, director of Radio Coca). The discourse was also embraced and proliferated by Ronda’s association of small and medium-sized enterprises (APYMER): ‘People have to stay more than one day. […] It has been proven that golf tourism is a very important engine of the economy of the Costa del Sol and Andalusia’ (interview, APYMER representative).

In contrast, the group of ecologists (Silvema-Serranía de Ronda) and the Water Defence Platform considered Los Merinos an exclusionary tourism development model imported from Costa del Sol, which would be of benefit to just a few.

These urban projects do not respond to the demands of the population, nor do they provide reasonable growth perspectives. […] [The plan] would have provided economic success for certain professionals: architects, lawyers, bankers … for them, it would have been fantastic [but not for us]. (interview, Silvema member)

The ecologists mistrusted external investors who offered financing and rapid employment, arguing that the jobs to be created would be temporary and of low quality. Similar projects in the region had resulted in the hiring of cheaper workers from outside the area, instead of local ones. Instead of reaping the benefits, Ronda would incur long-term social and public costs (e.g. for road maintenance, lighting, sanitation and waste disposal), all at the taxpayers’ expense. ‘It is bread for today and hunger for tomorrow’ (interview, former Mayor of Cuevas del Becerro).

The members of the Water Defence Platform had a different concept of progress, as they had previously accentuated in a documentary on their territorial notions: ‘Progress consists of creating fraternity, sensitivity, and identity. When a territorial landscape, which is essential to a people’s identity, is destroyed, this uproots its inhabitants’ (Jiménez, Citation2008). The social movement’s resistance to the commodification of land in Los Merinos land was intertwined with their desire to perpetuate family ties within the territory, thereby transmitting vernacular knowledge, rooted values and affective relations with the land (cf. Bebbington, Citation2000, Citation2009; Paerregaard, Citation2017; Van der Ploeg, Citation2008; Vos et al. Citation2020). Successive generations had seen the oaks growing in the Serranía de Ronda – holm oak meadows, representing high ecological and cultural value. As explained by the leader of the movement, Juan Terroba, the Water Defence Platform aimed to defend both the ecological properties of Merinos and the right to public access to this territory, in opposition to private appropriation. Not only had the earlier Merinos South project built a private motor racing circuit right in the middle of this ecological reserve, but also the land had already been purchased by a twin project (Merinos North), thereby prohibiting access to the public for hiking and recreation.

The company’s discourse denied the socio-environmental impact by arguing that the project was sustainable, with low urbanization density and a golf course. ‘The golf course represents a great ecological benefit for the area and its immediate surroundings.’ Moreover, its construction would provide ‘an improvement in the quality and image of tourist offerings, the recovery of degraded landscapes, the integration of pre-existing trees into the tourist complex, and the reforestation of areas at high risk of erosion’ (Fraga, Citation1995). Los Merinos would offer ‘low-density tourism as an alternative to coastal tourism’ (interview, director of the architect team of the General Urban Development Plan – PGOU Plan General de Ordenación Urbana). This low-density outlook nevertheless led to a dramatic removal of oak trees at the start of the project. As stated by Juan Terroba, ‘It is unimaginable how a group of people are destroying eight million square metres of Mediterranean mountain holm oaks, the most emblematic landscape of Serranía de Ronda’ (cited in Jiménez, Citation2008).

In addition to the threat of ecosystem destruction, the Water Defence Platform argued that the Merinos Norte project posed a hazard to regional water security and sovereignty. The project threatened to deplete an important water source for the region: the aquifer of the mountain ranges of Los Merinos, Colorado and Carrasco. The Ronda aquifer and the springs that supply water to Cuevas del Becerro and the municipalities of Serrato, Arriate and Setenil would be affected by water scarcity and contamination. As stated by the former Mayor of Cuevas del Becerro, ‘The village without El Nacimiento is inconceivable.’ In the broader environment, the project would have the potential to affect the important Guadalteba and Guadalhorce rivers.

The discourse of the Water Defence Platform was challenged by the company and the government of Ronda, who argued that sufficient water was available in Serranía de Ronda and that the project would not affect water security in the surrounding villages. ‘Here in the Sierra, there is enough water for both Merinos, in addition to supplying several municipalities of Málaga’ (interview, former Mayor of Ronda). The company also argued that Cuevas del Becerro could not be affected, as the Merinos aquifer was not connected to its spring. Even worse, they argued, water scarcity problems in Cuevas del Becerro were likely to be caused by the neighbours themselves, who would be likely to ‘steal the water through illegal wells’.

As clearly illustrated by the exchange described above, temporality was a key dimension in the opposing discourses. The dominant market-based discourse was characterized by a time horizon based on short-term interest rates and land prices. In contrast, the ecologists’ movement adhered to a time conception linked to long-term cycles, with a focus on sustaining ecological integrity for present and future generations.

The positioning of Ronda and Cuevas del Becerro in the conflict can be explained by their different socioeconomic realities. Although both municipalities have traditionally been strongly connected to agriculture, they have developed in different directions in recent decades. While Cuevas del Becerro has remained a mainly agrarian society, Ronda has lost its agrarian roots and shifted towards a socioeconomy based on tourism. Cuevas del Becerro has preserved and defended its smallholding agricultural system against latifundia, and its population therefore has a strong direct relationship with the natural and cultural landscape. It also has a history of resistance against the Francoist regime and in defence of their livelihoods (Prieto, Citation2017).

To enhance understanding concerning the origins of the different discourses, it is important to consider the political ideology and positioning of each group of actors. A former Mayor of Cuevas del Becerro represented the party Izquierda Unida, a leftist national party that was the only political party in the Ronda city council to oppose the project. In contrast, the Mayor of Ronda (2007–11), who had approved the implementation of the Los Merinos Norte project, represented the Partido Andalucista, a nationalist–regionalist party. He would later join the Partido Socialista Obrero Español because, in his view, that party attracted more private investment than any other (Duarte-Abadía, Citation2020). At the regional level, the political party that approved the territorial planning modifications necessary for the implementation of the project was the national social-democratic Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE). This case illustrates the regional reality, in which both political parties (PSOE and Partido Popular in Andalucía) favoured large-scale capitalist investments. The parties competed to obtain infrastructure projects as sources of funding for small municipalities and, in many cases, for private interests. Meanwhile, Izquierda Unida has generally opposed this model of urban development.

Decision-making power: authorities

Various authorities have disputed the shaping of the hydrosocial territory of Serranía de Ronda. Beyond formal authorities, actor alliances have used new forms of authority through their social networks and legal plurality. Project promoters have defended the land-market laws, while opponents have deployed the customary rights of local inhabitants to defend water access and territorial conservation.

Legal and political authorities

Ronda city council has supported the project throughout the years, regardless of political party (with the exception of Izquierda Unida). During the 1990s, the municipality of Ronda facilitated the project by adapting the PGOU General Urban Development Plan, which was supported by Andalusia’s regional government. The elaboration and approval of the PGOU was an obscure process that evaded all public tenders or democratic checks and balances (Diez Ripollés et al., Citation2011). This authority approved the new PGOU of Ronda in May 1994, one year after the same body had reclassified the land-use category of Merinos to ‘developable land’, so that the project could be developed. Next, the municipality signed the urban development plan, which neglected important elements of the environmental impact assessment. When the water authority (Agencia Andaluza del Agua) refused to grant a water concession to the project, the municipality of Ronda signed an agreement with the company, promising to supply water to Los Merinos Norte from Ronda’s water network. In doing so, they bypassed the official ruling according to which the municipality had no authority to concede water rights. The unconditional support from the local government to the company created a lack of control over the company´s activities.

In 2005, the Water Defence Platform appealed to the Superior Court of Justice. The main arguments in the allegation were the location of the project within a protected area and non-compliance with the environmental impact assessment. No conservation or protection measures were provided, and the water-availability studies were not ratified by the water authority (Huertas, Citation2005). In 2007, the Public Works Councillor requested the precautionary suspension of construction in order to prevent environmental damage. Nevertheless, the court’s ruling prioritized the prevention of potential economic damage to the company over the prevention of environmental damage, thereby denying the request to stop construction. Ronda city council did not wait for the result of the appeal, and the company immediately started clearing the land, logging more than 1100 holm oaks without the mandatory authorization. Both the business group and the socio-ecological movement made use of the judicial system to defend their interests. The business group argued that the project was legitimate because it was included in Ronda’s spatial planning. With the help of its attorney, the social movement appealed against multiple irregularities of the project, demanding respect for existing nature-protection figures.

Big-business authority: a powerful and deeply entangled social network

The business group managed to gain authority through allegedly illicit strategies, one of which was the creation of a complex business network. Promociones Club de Campo y Golf Ronda, S.L. was the local representative of a wider power structure. A criminology study by the University of Málaga (Diez Ripollés et al., Citation2011) analyses the complex web of enterprises behind the company, which included such national construction and water companies as Copisa and Fomento de Construcciones y Contratas. The strategy was to create a network of authorities that would obstruct the visibility of their actions and the individuals behind them. From 1995 to 2008, 50 companies were created around Merinos. Big-business actors with high-level political relationships formed part of these societies. One example was Luis Solana, a politician/entrepreneur, the former president of the Spanish public television network (TVE), and brother of the former Minister of Foreign Affairs. Another example was Jordi Pujol i Ferrusola, an entrepreneur and son of the former President of Catalonia. In 2014, the Economic Crime and Fiscal Unit of the National Police revealed that Jordi Pujol i Ferrusola had received more than €1 million for intermediation in the signing of the Merinos Norte contract (de Vega, Citation2014). This demonstrates the high level of interest that the project entailed.

The problem is that the economic interests were so great […] that, at every step they took, they became more corrupt. […] And now we know that some of those involved were members of the Pujol family. We were facing the mafia. (interview, former Environment Delegate, Malaga)

Government corruption was suspected at the local level as well. The Mayor of Ronda had allegedly received payments through a local newspaper. In 2011, the Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office investigated this matter in the 2011 Acinipo case involving urban corruption in Ronda. The former mayor, four councillors of his party, a lawyer and two entrepreneurs were investigated under suspicion of ‘bribery, misappropriation of funds, influence peddling, prevarication, false documentation, and money laundering’ (Viúdez, Citation2011; Viúdez & Pérez, Citation2011). The case was closed, however, due to lack of evidence. One of the incidents of bribery investigated in the case involved the newspaper La Gaceta de Ronda, which was owned by the mayor. According to El Observador newspaper, the company had paid €127,344 to the newspaper and that part of this amount had contributed to paying off the mortgage on the mayor’s house (El Observador, Citation2012). According to the socio-ecological movement, this newspaper was a vehicle for the project’s propaganda, and it had discredited the Platform and individuals opposing the project.

In addition to the government’s formal power, other entities – the media, associations and religious fraternities (hermandades) – thus had authority over decision-making processes due their influence over social opinion, principles and values. The company and the government supposedly created alliances with some of these authorities to justify the development of the project and ensure social acceptance. According to members of the social movement, the company had given gifts to the associations and religious fraternities, and the local government had favoured the funding of associations that supported the project.

Cultivating fear to control society

According to the social movement, the overall political atmosphere and social control in defence of the interests of the company was strong.

They made statements, comments, and attacks in a personal way. Even city council officials were threatened with expulsion if they did not submit in some way […] Ronda is a small town, and those comments were spread […] those who had less endurance were silenced. (interview, member of the socio-ecological movement)

The leader of the environmental group in Ronda was removed from his post as a policeman and suffered many personal threats and defamations. The business group used a strategy of threats and penal accusations to instil fear. Movement members and their families were taken to court for demonstrating against the project, as well as for other issues (e.g. for the alleged possession of illegal wells). The provincial media that covered the news of the Merinos was also taken to court for defamation. An English resident who had published an article in the British press expressing his opposition to the project and solidarity with the movement was accused of defamation and sued for €22 million. In all, the company filed 24 accusations against various people (Pérez, Citation2011). Although this strategy discouraged some people, it was an incentive for others to continue the struggle:

If they had been more intelligent, there would not have been so much rejection. Many of us, including myself, became more involved in response to the dirty methods and games that they were using. Someone from outside came to threaten our territory and threaten us. They were very direct threats. (interview, member of Silvema – Serranía de Ronda)

The Mayor of Cuevas del Becerro at the time also suffered defamation and threats:

When the strike was going to take place, some collectives that had been created to do the dirty work for the company began to appear. […] They presented documents in the town hall asking me how the general strike had been approved, accusing me of lying about the holm oaks. […] It reached the point where the promoter […] came to my house, asking me to blow off the strike. He did not try to buy me personally, but he did offer me something for the people: industrial land. And when I refused, he told me that they had the best legal team in Spain, and that they were going to defend their project tooth and nail. (interview, former Mayor of Cuevas del Becerro)

Social movement response: multiscale alliances

As mentioned previously, the environmental group cooperated with various civil-society groups and the Mayor of Cuevas del Becerro to create the Water Defence Platform. This alliance expanded as other actors joined the social movement, including the lawyer from Ronda (who advised and legally represented the movement), the local bird conservation foundation, and the Pro-Human Rights Association of Ronda. Beyond the local level, the Platform extended its alliances to non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil groups, including the New Water Culture Foundation, Greenpeace, the Grupo de Trabajo Valle del Genal (Genal Working Group) and the New Territory Culture group. These groups organized demonstrations and presented numerous allegations to the regional institutions and national courts, and Cuevas del Becerro organized a large strike. This was the first case in Spain in which an entire municipality participated in a strike, led by its mayor. The action was reported on the front page of the national newspaper El País, which made the case well known outside Serranía de Ronda.

To disseminate its discourse, the movement made alliances with various academics. For example, the University of Oviedo collaborated by conducting a study on the risks the project posed to the water security of the region. The study revealed that the springs of these villages are supplied by the carbonate aquifer located under Merinos and that they could be affected by contamination from pesticides and fertilizers used in the golf course, as well as by residual water leakage. In addition, there was a risk of overexploitation of the aquifer (Casares et al., Citation2009). In response, the company fortified its discourse on water abundance and commissioned two hydrological studies of the Merinos area to demonstrate that the project would not affect the surrounding populations. One study was conducted by a private company, concluding that the water resources were sufficient for consumption (Ferrándiz 48 G.I.A S.L. y Mayoral, Citation2004). The second study, which was conducted by the University of Sevilla on commission by the same company, concluded that the risk of pollution was very low (Chiara et al., Citation2004). The official Agencia Andaluza del Agua river basin confederation dismissed the studies as unreliable. According to them, the project could have an impact on the water supply of nearby populations, as well as on the river basins connected to these underground waters, including the Guadalhorce and Guadiaro valleys (Agencia Andaluza del Agua, Citation2005).

Norms in conflict

In Spain, various legal tools exist within the field of territorial planning in order to control urban growth and guarantee the adjustment of spatial distributions to biophysical, economic and socio-cultural conditions. The General Urban Development Plan (PGOU) operates at the municipal level and has a duration of 10 years. It classifies the land in the municipality into the categories of urban, non-urban or developable land area, thereby determining where construction is and is not possible. Urban land must meet the basic conditions for establishing such public infrastructural services as sewage, drinking water, road networks and electricity. Non-urban land is regarded as protected due to its high ecological, archaeological and cultural importance. The category of developable land is crucial for presenting any kind of urban project, and it must be approved by the municipality and regional government (in this case, Ronda city council and the Junta de Andalucía, respectively). Within this category of ‘non-programmed developable land’ (suelo urbanizable no programado), it allows the local government to stock land for future developments. Land development depends on the approval of an initial plan known as the urban development plan (Plan de Actuación Urbana – PAU) and a detailed urban development plan known as the partial plan for urban planning (Plan Parcial de Ordenación – PPO). The approval of the PPO by the local and regional government depends on a positive environmental impact assessment (Declaración de Impacto Ambiental – DIA) and a water concession from the water authority. The DIA is approved by the provincial or regional environmental delegation and the municipality.

As mentioned previously, Ronda city council and the regional Department of Public Works approved a PGOU in 1991 that modified the classification of several areas in the north of Ronda from rural to developable land. In addition, it provided for the implementation of residential tourism projects there. In particular, it specifically established the conditions for the construction of golf courses and urbanization projects, including the allocation of 15% of the houses to be built to the council. For the Merinos Norte area, the PGOU even stated the maximum number of houses allowed (800) and specified the timeframe for the construction of the golf course (Plan General de Ordenación Urbanística [General Urban Development Plan], Citation1991). The plan that followed the PGOU, the special urban planning plan (Plan Especial de Ordenación Urbana – PEOU) considered that the highly valuable ecosystem of los Merinos was compatible with alternative uses, and that changes in soil classification were pioneering solutions to create greater profit (Aud, Citation1990). The changes in soil classification were considered ‘innovative and radically different solutions’ for greater profit (Aud, Citation1990). This is justified by the need for an economic model for the future of Ronda. The new plan was described as a source of opportunity, warning that it was not convenient to limit the high-quality production and development possibilities of Ronda (Aud, Citation1990).

The norms stated in these plans were in conflict with those of the Water Defence Platform, which argued that the compatibility of Merinos project with the physical environment was questionable, for various reasons. First, the location of the project (12 km from the town of Ronda) was contrary to the Mediterranean compact-development model that would later be promoted by spatial planning legislation. More specifically, the 2001 Spatial Plan of Andalusia (abbreviated in Spanish to POTA) established this model as a guideline for the coherent and sustainable development of urban areas, and the 2002 Law of Urban Planning of Andalusia (abbreviated in Spanish to LOUA) stated that the construction of new housing must be adjacent to the urban centre (BOE (Official State Gazette), Citation2003). Second, the project planned to transform the majority (69%) of Los Merinos, which was not in compliance with the conditions of the environmental impact assessment. According to this assessment, the soil transformation could not exceed 25% of the territory, and the conservation of the vegetation and fauna had to be assured both during and after the construction phase. Third, the project posed a risk to water security in the region. This was stated in the report issued by the aforementioned Agencia Andaluza del Agua river basin confederation, in response to the water-concession petition. The hydrogeological unit from which the extraction of water was requested drains into nearby subsystems (e.g. the Guadalhorce) that are prone to water deficiency, especially during the summer. The project would affect the minimum flows of these subsystems. The water authority also considered that the project was highly likely to have an impact on the villages of Cuevas del Becerro and Arriate (Agencia Andaluza del Agua, Citation2005). Moreover, it considered that the flow demanded by the project (520 L/inhabitant/day) was excessive, taking into consideration the lack of rain in 2005.

A fourth, very important reason for the Water Defence Platform to question the compatibility of Merinos project with the physical environment was that the project had been planned within an international protection area, the Sierra de las Nieves Biosphere Reserve, which had been established to recognize the ecological value of the area and to foster its sustainable development. The company and the government nevertheless justified the implementation of the project based on the non-binding nature of the biosphere reserve. Only the core zone (a strictly protected ecosystem) is legally protected by the natural park. The Merinos land belongs to the ‘transition zone’ – an area in which the greatest activity is allowed, albeit in a manner that is socio-culturally and ecologically sustainable. This classification was also criticized by the social movement, which claimed that the land should be classified as a buffer zone – an area surrounding the core area in which uses are limited. According to the social movement, the consultancy in charge of the biosphere reserve zoning, Consultora Mediterráneo, S.A., had not been objective in the classification of the area. As confirmed in a study on Los Merinos Norte by Diez Ripollés et al. (Citation2011), the company had previously published a report on the areas of the Merinos project in which it recommended eliminating the protection figure as (complejo serrano) area. This study had been used to justify the change in land classification in the 1991 PGOU. According to CitationDiez Ripollés et al., the position of the consultancy could be explained by the fact that several of the team members had played a role in the approval of the Merinos Norte project. For example, one architect had worked in the Public Works Department of the Andalusian regional government – the body in charge of the final approval of the PGOU – and another architect had signed the Merinos urbanization project.

Despite its inability to provide official protection in Los Merinos, the biosphere reserve provided important support for the arguments of the social movement. Reports in the national press frequently mentioned the protection figure as the main indicator of the ecological value of the territory. In addition, some members of the Man and the Biosphere (MAB) committee participated in the conflict, explicitly criticizing the Merinos Norte project for representing an unsustainable development model and for the possible contamination of the aquifers. The former chair of the committee warned that if the project were to be carried out, together with another nearby project, it could result in the area’s exclusion from a new intercontinental biosphere reserve that was being planned with Morocco. In an interview for the national newspaper El País, the former committee chair stated: ‘When talking about sustainable development, concepts like rural tourism or agribusiness come to mind. But […] two golf courses and 800 chalets is very much about development and not very much about sustainability’ (Jan, Citation2004). Such statements influenced the perspectives of society and regional politicians concerning the project and the threat that it entailed.

Access to land and water resources

Access to the land and water of Merinos was disputed on one side by the business group and Ronda city council and, on the other, by the social movement and provincial authorities. In the attempt to gain control over these resources, each party tried to deploy the rules, authorities and discourses outlined above, albeit according to different strategies.

The business group primarily used its large economic capital. The Golf and Country Club Ronda company, which was owned by Swiss investors, bought the Los Merinos land, which consisted of two rural parcels, from local owners in 1990 (Diez Ripollés et al., Citation2011). The purchase was followed by a speculation process. In 2003, the Golf and Country Club Ronda company sold the land rights and the four companies owning the Merinos Norte project (Club de Campo de Ronda, S.A., Club de Campo Los Merinos, S.A., Sporting Club Ronda, S.A., and Sporting Club los Merinos, S.A.) to three other companies: Ciudad Jardín de Lindón, S.L., Metálicas Cabanés, S.L., and J. M. Legión Española 1. These companies subsequently resold the land rights to Club Náutico Marina Canal de la Fontana, S.L., which was later renamed Promociones Club de Campo y Golf Ronda, S.L. This process of buying and selling the land over the course of 15 years yielded significant economic benefits for the sellers. In the last operation, the price of the land was more than €15 million, having multiplied 15 times since the 1990s (Diez Ripollés et al., Citation2011). The last purchasing company, Promociones Club de Campo y Golf Ronda, started the process of implementing the Merinos Norte project in 2006. In an effort to increase the price even further, the company did everything possible to promote the adoption of regulations that would allow urbanization, as explained above. In summary, the acquisition of land to the company’s benefit was facilitated by the modification of norms and the manipulation of authorities.

In addition to the appropriation of land, the project entailed a risk of water-grabbing (Duarte-Abadía, Citation2020). The business group’s powerful social network included the national enterprise Constructora Pirenaica, S.A. (abbreviated to Copisa). This was the company responsible for felling the holm oaks in order to build the water-supply network and the sewage system. As noted by Díez Ripollés et al. (Citation2011) and Delgado (Citation2016), Copisa was founded in 1959 to assist the work of the Fuerzas Electricas de Cataluña (FECSA) with regard to hydropower development in Catalonia. In its turn, FECSA was founded in 1951 by Juan March, with support from the Franco regime (Delgado, Citation2016). Copisa is currently a multinational company that builds mega-hydraulic projects in various countries, in association with Degremont, a water-management company and subsidiary of the Suez Group. As explained by CitationDelgado, Copisa and Degremont cooperate with La Caixa bank to control the General Water Society of Barcelona (also known as the Agbar Group, and Copisa has close ties to the Catalan business group Fomento de Construcciones y Contratas (FCC), which controls AQUALIA. Since 1993, FCC has managed water supply, sanitation and purification services in Ronda. With the Merinos Norte Project, AQUALIA hoped to do the same (Delgado, Citation2016). As further noted by CitationDelgado, another reason that Copisa and FCC were interested in developing the Merinos Norte project involved the possibility of controlling the water from the Sierra de Los Merinos aquifers (Duarte-Abadía, Citation2020).

According to Veldwisch et al. (Citation2018), land-grabbing processes around the world are motivated in part by the intention to gain control over water. Such water-grabbing includes control over the ways in which water is to be used, by whom, when, for how long and for what purposes. In the case of Merinos and related territorial water uses, this situation was unacceptable to the socio-ecological movement. To the members of this movement, water rights were closely connected to the duty to defend the common lands (Duarte-Abadía, Citation2020). Water is the lifeblood of Andalusian towns. It acts as a social and communal asset that represents a cultural, ecological and socioeconomic heritage (Aguilera, Citation1995). It further represents identity and identification, a sense of belonging to the territory.

We fight to conserve the diversity of ecosystems, the richness of the soil. We do not want to follow the model of tourist destruction. Look at the cases of Marbella, Estepona, Benahavís, and other cities of the Costa del Sol. I do not think that they are examples to repeat. (interview, movement leader Juan Terroba)

The Water Defence Platform used diverse strategies to oppose the appropriation of land and water resources by the company. Their efforts included the creation of alliances with the academy and provincial authorities, awareness-raising, mobilization, demonstrations and a strike, as well as the use of legal mechanisms. Through alliance-building and judicial strategies, the movement was able to call a temporary halt to the Merinos project.

As mentioned above, the governmental entity with decision-making power over water (Agencia Andaluza del Agua) proved to be a key factor in the conflict. This authority denied the water concession requested by the company, arguing that the demand exceeded the availability of water resources, according to the provisions of the Basin Hydrological Plan. The company then appealed to the Supreme Court. In 2015, however, the court ratified the decision and annulled the validity of the Merinos project plans due to the lack of water supply. It further ruled that the project did not have the mandatory water concession for Los Merinos residential tourism and, moreover, that the Ronda municipality’s agreement with the company to provide water from the municipal network as an alternative was invalid. This resolution resulted in the paralysis of the project – a late victory for the movement, 10 years after the judicial process had started.

The project standstill did not imply that land conservation and water security would be assured in future. The Merinos land continues to be classified as ‘developable land’, meaning that another project could potentially be carried out. The classification is unlikely to be changed because it could radically influence the municipality’s financial situation due to the policy of aprovechamientos urbanísticos. Advance payments amounting to €15 million had been made by Promociones Club de Campo y Golf Ronda, S.L. As observed by Melgar (Citation2016), although investment-development enterprises behind this company have been claiming a refund of this amount, the municipality of Ronda has spent it already, and it is currently unable to bear that amount of debt. The company has sued the city council. The municipality’s excuse for not refunding the money is that the project could still be implemented if the company were to comply with the legal conditions regarding water supply. Reclassifying the land use to rural, thereby precluding urban projects, would invalidate this argument. For this reason, the classification as ‘developable land’ remains in force. Moreover, Promociones Club de Campo y Golf Ronda, S.L. recently declared bankruptcy, and the Los Merinos Norte land became the property of Santander bank. The social movement is afraid that the bank will eventually sell the land to a company in order to implement another urban project. The approval of any such project, however, would again depend on the willingness of the Ronda city council.

Although new, recently enacted environmental laws do offer more protection, these laws could potentially be superseded by another legal figure: the Special Plan. If the municipality deems the project an Act of Public Interest (with the same priorities as those of the business group: creating economic growth, jobs and social benefits), this instrument would open up the possibility of any type of action, even on protected rural land (Flores, Citation2019). ‘The projects are coming back at a good pace. It may be that they will be implemented again. Not Merinos, because it was clearly even a business mistake. But others might’ (interview, representative of the Regional Office for Agriculture). One possible future threat could involve the new law of urban and spatial planning, which is being proposed by the current government formed by Partido Popular and Ciudadanos, through the draft law Ley de Impulso para la Sostenibilidad del Territorio de Andalucía (Law of Andalusian Territory Sustainability Promotion) (Junta de Andalucía, Citation2020). This new law would reduce the number of land categories to two – urban and rural – thereby eliminating the category of ‘developable land’. The objective of the new law is to accelerate administrative processes in order to promote the economy after the COVID-19 crisis. These new conditions could provide incentives for classifying more land as ‘urban’.

In summary, despite the important victories achieved by the social movement, the future of land and water control is unknown, and a new project could thus still be implemented. Although the business group’s economic-investment discourse has created major social and environmental problems, it has not been discredited within the city council. Business and political figures who bet on environmental injustices and Ronda’s unsustainable futures are not being held accountable. On the contrary, dominant discourses and hidden power structures are sturdy, and some segments of Ronda’s population are even holding the social movement accountable for Ronda’s financial and ‘modern development’ debt. Resistance to new scenarios of environmental injustice will once again depend on the efforts of the social movement.

Discussion and conclusions

Indiscriminate urban-style development to foster mass tourism has been deeply transforming the Spanish landscape ever since the Francoist regime. Many small municipalities with few possibilities for generating economic income have prioritized capitalist–financial inflow over sustainable territorial planning, promoting unrealistic projects that fail to respond to the actual needs of their citizens. Construction and land speculation have resulted in the destruction of vast natural and rural areas, as well as the creation of leisure islands that are completely disconnected from the local population. In response to these poor water and land governance practices, strong social and environmental resistance movements have been formed at both the national and local levels. Numerous conflicts have arisen in recent decades (and many are still ongoing) involving opposition between discourses on progress and discourses of environmental justice. The |protection of water and land resources in tourist areas in Spain, especially along the east coast, will depend on the efforts of these resistance groups and the degree of social endorsement (e.g. Araque & Crespo, Citation2010; Del Romero-Renau, Citation2015; Nel.lo, Citation2007; Salcedo & Campesino, Citation2015).

This paper analyses a specific case of resistance against a tourism complex, the Merinos project, using the ERA framework. The analysis begins with the discourses used by both the promoters and the opponents of the project, proceeding to the decision-making power held by the two groups of actors. The analysis then proceeds to the norms that were contested and, finally, to the resulting access to water and land. The analysis reveals the dynamics of power relations in this territorial conflict. It further exposes the strategies that the various actors have used to materialize their notions of territory (e.g. building alliances with other actors at the local and higher levels, producing knowledge and making use of the judicial system). The uncontrolled expansion of tourism could serve as a catalyst for the colonization of Serranía de Ronda by treating land as a commodity and by co-opting local authorities to change their urban-ordering plans. The interference of large, powerful private-capital business networks is blurring distinctions between legality and illegality, while disturbing public administrative boundaries and environmental-protection jurisdictions. In the case of Los Merinos, public–private alliances have often led official authorities to set aside their key roles as public servants and protectors of the common good, and instead to make decisions that will benefit the private sector.

As demonstrated by the Merinos encounters, the content and scale of conservation policy – particularly with regard to hydrosocial territories – are not fixed, but flexible, responding to the balances (and imbalances) of power between state regulation, market logic and the cultural anchor of the community (cf. Sañudo et al., Citation2016; De Stefano & Hernandez-Mora, Citation2018; Sanchis-Ibor et al., Citation2017; cf. LaVanchy & Taylor, Citation2015). It is therefore essential for both business and territorial-defence networks to capture political alliances at the regional, national and international levels. Multiscale coalitions provide the necessary political clout and support the particular discourses of these networks, in addition to providing technical, scientific, economic and social tools for territorial ordering (and reordering).

The social movement opposing the Merinos project attracted an array of different, complementary actors, each having advocacy capacity within the respective social networks (cf. Bebbington et al., Citation2010; Dupuits, Citation2019; Horowitz, Citation2012). In this way, their actions could transcend and spread out across regional, national and international scales (cf. Hoogesteger et al., Citation2016; Hoogesteger & Verzijl, Citation2015; Shah et al., Citation2019; Villamayor-Tomas & García-López, Citation2018). The constant monitoring of the political/business actions enhanced the movement’s social and legal strength to attack the irregularities being committed. The movement acquired in-depth technical, political and legal knowledge of all fields in which the business group was involved. This made it possible to mobilize actors and address/manipulate rules on all fronts. For example, one important aspect involved the manner in which the movement mobilized Spain’s water-legal framework, which is largely responsible for the current success of the Water Defence Platform. The territorial planning and land-use categories of Los Merinos have not been modified, however, and the hydrosocial territory continues to be defined as ‘developable land’. The future of Merinos will depend on the presence of new actors with business interests in the area, the alliances formed with the local and regional government, and, most importantly, the capacity of the social movement to maintain or acquire decision-making power over the territory’s boundaries, substance, values and meaning.

The results of this study demonstrate the importance of social movements in defending or steering the process of territorial ordering, including the monitoring of and opposition to territorial misappropriation. The sharing and mobilization of affective, spiritual and cognitive values that the inhabitants attach to their hydrosocial territory ultimately played a fundamental role in their struggle. Claiming the right to live in the place where they were born and to protect the natural environment inherited from their ancestors is closely intertwined with territorial struggles concerning the control of and access to land and water. The existence of these deeply rooted, intergenerational perspectives and modes of territorial belonging is a powerful source of resistance against the classic, dominant projects and rationalities that insist on treating nature as a mercantile, transferable and, in many cases, disposable good. Faced with the threat that capitalist urban projects planned by high-modernist ruling elites pose to the land and water rights of local populations, these movements are key social actors in the fight for environmental justice. At the same time, however, it is necessary to acknowledge that the mere existence of such conflicts is a fundamental symptom of poor water governance, lack of transparency and lack of true public participation. To avoid the perpetual recurrence of these conflicts, it is of the utmost importance for the decision-making process not to be restricted to the sphere of government and/or private investors, but to include all stakeholders, and particularly local inhabitants. The frequency and intensity of Spain’s socio-environmental conflicts indicate that public participation mechanisms are neither effective nor respected. It is crucial to create platforms that can bring together social and environmental groups with local and national governments to debate territorial planning and to join forces to address public and common affairs.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of Silvema-Serranía de Ronda (Ecologistas en Acción) and all the individuals involved in the social movement who provided key information and documentation for this research. We thank the former mayors of Ronda, Cuevas del Becerro, Arriate and Setenil. We thank the local journalist who covered the conflict and the representatives of the local media, the business association, civil associations, government representatives and local inhabitants of Ronda. We thank the academics from Málaga University and Sevilla University who provided information on the hydrology of Ronda. We also thank the representative of the promoter company and the architect responsible for Ronda’s territorial planning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Achterhuis, H., Boelens, R., & Zwarteveen, M. (2010). Water property relations and modern policy regimes: Neoliberal Utopia and the disempowerment of collective action. In R. Boelens, D. Getches, & A. Guevara-Gil (Eds.), Out of the mainstream. Water rights, politics and identity (pp. 27–55). Earthscan.

- Agencia Andaluza del Agua. (2005). Informe de compatibilidad con el Plan Hidrológico de Cuenca [Compatibility report with the Basin Hydrological Plan]. Consejería de Medio Ambiente.

- Aguilera, F. (1995). El agua como activo social. In J. González & A. Malpica (Eds.), El agua. Mitos, ritos y realidades (pp. 359–374). Diputación provincial de Granada. Anthropos editorial.

- Aledo Tur, A. (2008). De la tierra al suelo: La transformación del paisaje y el nuevo turismo residencial. [From soil to land: The transformation of the landscape and the new residential tourism]. Arbor, 184, 729. https://doi.org/10.3989/arbor.2008.i729.164

- Allan, T., Keulertz, M., & Woertz, E. (2015). The water–food–energy nexus: An introduction to nexus concepts and some conceptual and operational problems. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 31(3), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2015.1029118

- Araque, E., & Crespo, J. M. (2010). Conservation versus développement? Une nouvelle situation conflictuelle dans les parcs naturels andalous. Collection EDYTEM. Cahiers de géographie, numéro 10, 2010. Espaces protégés, acceptation sociale et conflits environnementaux (pp. 113–124). Persée. https://doi.org/10.3406/edyte.2010.1119

- Aud, S. A. (1990). Ronda. Plan Especial de Ordenación y Plan Especial del Casco Histórico. Avance [Ronda. Special ordination plan and special plan of the historical quarter. Progress]. Geometría Monografías.

- Baud, M., Boelens, R., & Damonte, G. (2019). Nuevos capitalismos y transformaciones territoriales en la Región Andina. [New capitalisms and territorial transformations in the Andean region]. Estudios Atacameños, 63, 195–208. https://doi.org/10.22199/.0718-1043-2019-0033

- Bebbington, A. (2000). Re-encountering development: Livelihood transitions and place transformations in the Andes. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 90(3), 495–520. https://doi.org/10.1111/0004-5608.00206

- Bebbington, A. (2009). Contesting environmental transformation: Political ecologies and environmentalisms in Latin America and the Caribbean. Latin American Research Review, 44(3), 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1353/lar.0.0119

- Bebbington, A., Humphreys, D., & Bury, J. (2010). Federating and defending: Water, territory and extraction in the Andes. In R. Boelens, D. Getches, & A. Guevara (Eds.), Out of the mainstream: Water rights, politics and identity (pp. 307–327). Earthscan.

- BOE (Official State Gazette). (1997, April 15). Liberalisation measures in the field of soil and vocational schools law 7/1997 of 14 April [BOE No. 90]. (In Spanish).

- BOE (Official State Gazette). (2003, January 14). Andalusian Urban Planning Law 7/2002 of 17 December [BOE No. 12]. (In Spanish).

- Boelens, R. (2015). Water, power and identity. The cultural politics of water in the Andes. Routledge.

- Boelens, R., & Gelles, P. H. (2005). Cultural politics, communal resistance and identity in Andean irrigation development. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 24(3), 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0261-3050.2005.00137.x

- Boelens, R., Hoogesteger, J., Swyngedouw, E., Vos, J., & Wester, P. (2016). Hydrosocial territories: A political ecology perspective. Water International, 41(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2016.1134898

- Boelens, R., & Vos, J. (2014). Legal pluralism, hydraulic property creation and sustainability: The materialized nature of water rights in user-managed systems. COSUST, 11, 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2014.10.001

- Casares, E. M., Fernández, B. G., & Gil, F. J. M. (2009). Estudio geológico e hidrogeológico del entorno de la sierra de los Merinos – Ronda y Cuevas del Becerro (Málaga) [Geological and hydrogeological study of the environment of the Sierra de los Merinos – Ronda and Cuevas del Becerro (Málaga)]. Oviedo University.

- Chiara, E. C., García, A. D., Ascaso, J. O., & Guerrero, M. A. (2004). Informe sobre consumo de agua, riesgo de degradación del suelo y de contaminación de acuíferos por dos campos de golf en Los Merinos Norte (Ronda, Málaga) [Report on water consumption, risk of soil degradation and contamination of aquifers by two golf courses in Los Merinos Norte (Ronda, Málaga)]. Departamento de Ciencias Agroforestales. Universidad de Sevilla.

- De Stefano, L., Fornés, J. M., López-Geta, J. A., & Villarroya, F. (2015). Groundwater use in Spain: An overview in light of the EU Water Framework Directive. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 31(4), 640–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2014.938260

- De Stefano, L., & Hernandez-Mora, N. (2018). Multi-level interactions in a context of political decentralization and evolving water-policy goals: The case of Spain. Regional Environmental Change, 18(6), 1579–1591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1318-6

- De Vega, B. G. (2014, September 16). La corrupción política. La Policía vincula la trama del caso Pujol a un macroproyecto urbanístico en Ronda. Political corruption. [The Police links the plot of the Pujol case to a macro urban development project in Ronda]. El Mundo. Retrieved from: https://www.elmundo.es/andalucia/2014/09/16/5417f43c22601d62718b4571.html

- De Vos, H., Boelens, R., & Bustamante, R. (2006). Formal law and local water control in the Andean region: A fiercely contested field. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 22(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900620500405049

- Del Romero-Renau, L. (2015). Geografia dels conflictes territorials a València i la seua àrea metropolitana. Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica, 61(2), 369–391. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/dag.230

- Delgado, M. (2016). Los megaproyectos como forma de apropiación de riqueza y poder en Andalucía. In M. Delgado & L. Del Moral (Eds.), Los Megaproyectos en Andalucía. Relaciones de poder y apropiación de riqueza (pp. 13–47). Aconcagua libros.

- Diez Ripollés, J. L., Gómez-Céspedes, A., & Aguilar Conde, A. (2011). Los Merinos Norte. Fenomenología de un macroproyecto urbanístico [Merinos Norte. Phenomenology of an urban macroproject]. Tirant lo Blanch.

- Duarte-Abadía, B. (2020). Utopic hidrosocial territories, transformations and water justice struggles in Colombia and Spain [Ph.D. Thesis]. Center for Latin American Research and Documentation (CEDLA). University of Amsterdam.

- Duarte-Abadía, B., & Boelens, R. (2016). Disputes over territorial boundaries and diverging valuation languages: The Santurban hydrosocial highlands territory in Colombia. Water International, 41(1), 15–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2016.1117271

- Duarte-Abadía, B., & Boelens, R. (2019). Colonizing rural waters. The politics of hydro-territorial transformation in the Guadalhorce Valley, Málaga, Spain. Water International, 44(2), 148–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2019.1578080

- Duarte-Abadía, B., Boelens, R., & Du Pré, L. (2019). Mobilizing water actors and bodies of knowledge. The multi-scalar movement against the Río Grande Dam in Málaga, Spain. Water, 11(3), 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11030410

- Dupuits, E. (2019). Water community networks and the appropriation of neoliberal practices: Social technology, depoliticization, and resistance. Ecology and Society, 24(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10857-240220

- El Observador. (2012, March 14). Sumario caso Acinipo (II entrega) [Acinipo case summary (II delivery)]. https://revistaelobservador.com/sociedad/6013-sumario-caso-acinipo-ii-entrega-los-merinos-financiaron-en-un-90-el-periodico-de-marin-lara-con-mas-de-127000-euros-con-los-que-se-pago-entre-otras-cosas-letras-de-la-casa-del-exalcalde-de-ronda-en-el-rocio

- Escobar, A. (2008). Territories of difference: Place, movements, life, redes. Duke University Press.

- Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the pluriverse. Duke University Press.

- Feindt, P. H., & Oels, A. (2005). Does discourse matter? Discourse analysis in environmental policy making. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 7(3), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080500339638

- Ferrándiz 48 G.I.A S.L. y Mayoral. (2004). Estudio hidrogeológico de la finca ‘Merinos Norte y su entorno’. Término municipal de Ronda.

- Fletcher, R. (2017). Environmentality unbound: Multiple governmentalities in environmental politics. Geoforum, 85, 311–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.06.009

- Flores, J. (2019, September 26). Ronda inicia el proceso para renovar su plan general de ordenación urbana. Málaga Hoy. www.malagahoy.es/provincia/Ronda-Plan-General-Ordenacion-Urbana-PGOU_0_1395160892.html

- Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings 1972–1978, ed. C. Gordon. Pantheon.

- Fraga, A. D. (1995). Proyecto Refundido del Plan Parcial de Ordenación ‘Merinos Norte’ Ronda. Colegio de Ingenieros de Caminos Canales y Puertos.

- Fraser, N. (2000, May/June). Rethinking recognition. New Left Review, 3, 107–120. Retrieved from: https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii3/articles/nancy-fraser-rethinking-recognition

- Hoogesteger, J., Boelens, R., & Baud, M. (2016). Territorial pluralism: Water users’ multi-scalar struggles against state ordering in Ecuador’s highlands. Water International, 41(1), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2016.1130910