ABSTRACT

Political theorists argue that justice for cultural groups must account for socioeconomic distribution, political representation and cultural recognition. Combining this tripartite justice framework with settler colonial theory, we analyse novel data sets relating to Aboriginal peoples’ water experiences in south-eastern Australia. We construe persistent injustices as ‘water colonialism’, showing that the development of Australia’s water resources has so far delivered little economic benefit to Aboriginal peoples, who remain marginalized from decision-making. We argue that justice theories need to encompass a fourth dimension – the vitally important socio-ecological realm – if they are to serve as conceptual resources for advancing Indigenous peoples’ rights and needs.

Introduction

Indigenous peoples worldwide demand self-determination in their political, economic and socio-cultural affairs.Footnote1 While no universal definition exists, the principle of self-determination emphasizes the rights of Indigenous peoples to make their own political, socioeconomic and cultural decisions. In struggles for self-determination, Indigenous peoples seek to maintain or re-establish the capacity to govern their customary territories, including inherent rights to use and protect their lands and waters (Coombes et al., Citation2012; Robison et al., Citation2018). These struggles are particularly complex in settler-colonial contexts where settler-states and their institutions have appropriated natural resources and caused significant widespread environmental degradation (e.g., Austin-Broos, Citation2013; Berry & Jackson, Citation2018; Poelina et al., Citation2019). Land and resource regimes that marginalize Indigenous peoples tend to be deeply entrenched in settler-colonial states; Indigenous jurisdiction is only tenuously recognized at best (Alfred, Citation2009; Austin-Broos, Citation2013; Robison et al., Citation2018; Weir, Citation2009).

Indigenous-state relations face growing international scrutiny, with some settler-colonial states introducing recognition mechanisms to respond to Indigenous land and resource claims (Balaton-Chrimes & Stead, Citation2017; Barcham, Citation2007). However, these mechanisms are generally formulated with little or no Indigenous input and at best usually offer limited and restrictive outcomes. Furthermore, they commonly essentialize Indigenous rights (e.g., confine them to ‘traditional’ or ‘pre-colonial’ forms) and render them subservient to the rights and interests of the majority settler population (Foley & Anderson, Citation2006; Moreton-Robinson, Citation2003).

Indigenous claims to freshwater exemplify the tensions in these settler-colonial political relations and environmental governance regimes. Water and water places are crucial to Indigenous peoples’ spirituality, well-being, livelihoods and identities, and their aspirations for self-determination span cultural, political and socioeconomic dimensions (Robison et al., Citation2018). Water is an essential element in complex attachments to place and the reciprocal, ethical relations that bind people and their territories (Te Aho, Citation2010; Bates, Citation2017; Hemming et al., Citation2019). In many societies, water is an animate being, sometimes described as mother or the lifeblood of a territory (Anderson et al., Citation2019; Yates et al., Citation2017). Settler-states typically obstruct Indigenous peoples’ rights to water (Boelens et al., Citation2018; Jackson, Citation2018b).

Unequal access to water and the political processes that direct management are fundamentally rooted in colonialism (Berry & Jackson, Citation2018; Curley, Citation2019b; Estes, Citation2019; Gibbs, Citation2009; Poelina et al., Citation2019; Robison et al., Citation2018; Weir, Citation2009). Imperial conquest and colonization resulted in dispossession and displacement of land and water tenures, while development dramatically transformed the waterscapes of Indigenous territories. Colonial expropriation of water deprived communities of their means of subsistence, interfered with lifeways and traditions founded on water cultures and debilitated social institutions, and thereby further eroded the political power of Indigenous peoples to influence subsequent resource allocations. Kul Wicasa scholar Nick Estes (Citation2019, p. 133) describes colonial water expropriation as an ongoing project: ‘Water is settler colonialism’s lifeblood – blood that has to be continually excised from Indigenous people’.

Indigenous water justice claims have garnered increased attention globally over recent decades (Jackson, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Jiménez et al., Citation2014; Taylor et al., Citation2019), including from policy-makers, researchers and governments. This study contributes to the emerging body of literature on Indigenous water rights in three ways. First, it furthers theoretical understandings of Indigenous water justice by engaging with settler-colonial theory and the tripartite justice theory developed by Fraser (Citation2000, Citation2009). Second, it describes and analyses present-day circumstances of Aboriginal people in Australia’s most intense water resource conflict. Third, it applies this tripartite justice framework to develop new conceptual resources with which to understand the phenomenon of water colonialism in south-eastern Australia.

This paper responds to key water justice questions posed by the editors of this special issue and is structured as follows. First, we outline and review the concept of Indigenous water justice and propose that a multidimensional conception of justice offers a helpful framework for examining and addressing the present condition of Indigenous water (in)justice. Here, we also introduce the concept of water colonialism (the why) as a framework that provides an explanation of the causes of contemporary and historical Indigenous water injustices and the barriers to the realization of water justice (the when). After contextualizing our south-eastern Australian case study and discussing the methodology, we reveal the multiple dimensions of water injustice experienced by Aboriginal peoples and Country (the who) in the New South Wales (NSW) portion of the Murray–Darling Basin (MDB) (the where), and as reflected in interview data and statistics on its land and water tenure and economic structure. The dimensions of injustice we focus on include continued misrecognition and exclusion from state water governance processes, damaging socio-ecological relationships, and ongoing expropriation of water and water-derived wealth from Aboriginal peoples (the what). We then bring together our main findings and discuss the implications for future policies to address these multiple dimensions of Indigenous water justice. In particular, we recommend that any responses by Australian governments to the socioeconomic dimension must overcome the underlying colonial legacies of dispossession and maldistribution of water, land and capital simultaneously.

It is important to note that the authors are non-Indigenous, white settlers living on unceded Aboriginal lands outside the case study location. This research was made possible through the work, support, insights and generosity of First Nations participants and peak bodies of the MDB with whom the first two authors have worked for several years. It is our intention that this work is useful in their struggles for water justice.

Water justice

Water can be considered a unique, essential resource that is unevenly distributed across space, making questions about its management and control inherently political. Water has attracted the interest of justice scholars because conflicts over water usually play out along axes of social differentiation, such as wealth, gender, class and race (Joy et al., Citation2014). There are many ways to conceptualize and analyse water justice (Joshi, Citation2015; Joy et al., Citation2014; Neal et al., Citation2014). What makes struggles for water justice so critically important and complex is that, as Indigenous peoples in both Turtle Island (North America) and Australia have long recognized, ‘water is life’ (Estes, Citation2019, p. 15; cf. Weir, Citation2009); it has many distinct biophysical, economic, political and socio-cultural qualities, and is imbued with meaning by people with diverse cultures and histories of water management (Boelens et al., Citation2018; Sultana, Citation2018; Yates et al., Citation2017).

The longstanding field of water justice studies (Syme et al., Citation1999) focuses on the distribution of water, stressing security of access to sufficient quantities of safe water and sanitation, bringing in issues of reliability, physical accessibility and affordability (Sultana, Citation2018). In efforts to broaden understandings, others argue that water justice transcends equitable water distribution and requires that we also consider the fairness of, and access to, institutional agendas and decision-making around water (Nikolakis & Grafton, Citation2014). Access to the political sphere – water governance and decision-making – has thus given rise to the study of procedural water justice (Lukasiewicz et al., Citation2013; Neal et al., Citation2014; Syme et al., Citation1999).

Water governance specialists and political ecologists have begun calling for more nuanced approaches to identifying and understanding water injustices; ones that extend beyond scarcity as the sole concern. They propose water justice be understood by examining both ‘formally accredited justice’, depicted in legal-positivist constructs, as well as ‘socially perceived justice and equity’. The latter is informed by and dependent on peoples’ own experiences in their socio-political contexts (Zwarteveen & Boelens, Citation2014, p. 147; see also Boelens et al., Citation2018; Joy et al., Citation2014). This approach to conceptualizing water justice commands a ‘re-politicization’ of water governance by making visible the hidden and uneven distribution of economic and political power (Joy et al., Citation2014). Re-politicization occurs by analysing and questioning how state and non-state actors are permitted (or otherwise) to participate in, control, decide and shape water governance, including water rules, water norms and truths (Zwarteveen & Boelens, Citation2014). This relational and contextualized approach to understanding water justice is also sensitive to how diverse peoples see, define, relate to and understand water and water justice (Boelens et al., Citation2018; Joy et al., Citation2014; Yaka, Citation2019; Zwarteveen & Boelens, Citation2014). It pays attention to the broader social, political and economic injustices in which water injustices are historically and contemporarily embedded (Joshi, Citation2015; Lynch et al., Citation2013; Mathur & Mulwafu, Citation2018; Sultana, Citation2018).

Indigenous water justice and injustice

By virtue of their colonial political and economic marginalization, Indigenous peoples around the world generally have relatively restricted access to productive water resources (Jackson, Citation2018a). Key international declarations and policy statements, and other works by Indigenous peoples (see below for examples), reveal that Indigenous perspectives on water justice share similarities with the framing above, but also differ in fundamental ways.

One difference is ontological. Notwithstanding considerable diversity in understandings, Indigenous peoples generally conceptualize water – and water justice – in terms of relationality and mutual dependence. Water is to be respected as kin, as a sacred, life-giving being, inseparable from and interconnected with relationships and obligations to landscapes, territories and past, current and future generations (Bakker et al., Citation2018; Estes, Citation2019; Hemming et al., Citation2007; McGregor, Citation2012, Citation2015; Morgan, Citation2011; Sam & Armstrong, Citation2013; Weir, Citation2009; Wilson, Citation2020). The authors of the Indigenous Peoples Kyoto Water Declaration (Citation2003), for example, state they ‘recognize, honor and respect water as sacred and sustains all life’. The authors of the Garma International Indigenous Water Declaration (Citation2008) assert, ‘water has a right to be recognized as an ecological entity, a being with a spirit and must be treated accordingly’. This is reflected, for example, in the Anishinaabek understanding that water justice explicitly depends on justice and healing for waters themselves and the trauma and distress they endure (McGregor, Citation2015). Indigenous water and water justice conceptualizations are determined by individual polities or Nations (Hemming et al., Citation2007; McGregor, Citation2012) and are therefore heterogeneous and diverse (Macpherson, Citation2019; Molina Camacho, Citation2016; Nikolakis & Grafton, Citation2015). Notwithstanding these differences, water is central to defining complex Indigenous attachments to and relationships with place (Te Aho, Citation2010; Jackson & Barber, Citation2013; Sam & Armstrong, Citation2013) and so for Indigenous peoples, the contamination, diversion or depletion of water bodies represents an attack on collective identities and survival as peoples (Jackson, Citation2018a).

A second difference is that Indigenous water injustice is entrenched in Indigenous peoples’ everyday experiences of and struggles against colonization. Expropriation of waters has generated multifaceted, multi-generational impacts for Indigenous peoples (Jackson, Citation2018a; Jackson et al., Citation2021; Robison et al., Citation2018; Sam & Armstrong, Citation2013; Walkem, Citation2006). The dispossession of and damage to Indigenous peoples’ lands and waters fractures spiritual and customary relationships with their territories. It interrupts economic and cultural activities, and erodes social and political systems. These significant injustices are reflected in sick and dying landscapes and ‘other-than-human relatives’ (Estes, Citation2019) as well as ongoing assaults on Indigenous health and well-being (Alfred, Citation2009; Sam & Armstrong, Citation2013). Climate change is likely to exacerbate many of these harms (Nikolakis et al., Citation2016). Despite these tremendous obstacles, Indigenous peoples still uphold their relationships with and responsibilities to place and water, actively resisting these forces (Estes, Citation2019; Lynch et al., Citation2013; McGregor, Citation2012; Poelina et al., Citation2019; Prieto, Citation2016), including at the global scale through the international Indigenous water justice movement (Jackson, Citation2018a).

Indigenous water justice is part of broader struggles for environmental and social justice, self-determination and sovereignty (Curley, Citation2019a; Estes, Citation2019; Hemming et al., Citation2019; Nikolakis et al., Citation2016; Prieto, Citation2016; Sam & Armstrong, Citation2013; Walkem, Citation2006; Wilson, Citation2020; Yazzie, Citation2013). Advocates and scholars argue for responses informed by Indigenous perspectives and priorities (McLean, Citation2007; Taylor et al., Citation2016; Weir, Citation2009; Wilson, Citation2020). One approach suggested by Robison et al. (Citation2018) conceptualizes Indigenous water justice as integral to self-determination, the foundational concept of international Indigenous rights law (see also Hemming et al., Citation2007). Rights to water are a precondition for exercising the right to self-determination, across intertwined socioeconomic, cultural and political dimensions (Robison et al., Citation2018).

Indigenous water justice can be further specified through another multidimensional formulation of justice, one advanced by political theorist Nancy Fraser (Citation2000, Citation2009). This approach responds to the distinctiveness of justice claims by cultural groups which must not only account for socioeconomic distribution but also address political representation and cultural recognition (Fraser, Citation2009; Jackson, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; McLean, Citation2007; Schlosberg, Citation2004). As argued by McLean (Citation2007), Jackson (e.g., Jackson, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Jackson & Barber, Citation2013) and Wilson (Citation2020), water justice for Indigenous peoples includes the equitable redistribution of water rights, plus legal, jurisdictional and cultural recognition, as well as fair and just participation and representation in water governance on terms set and determined by Indigenous peoples. Fraser’s framework accommodates the plurality of Indigenous conceptualizations of water and water justice. The approach also emphasizes the necessity for state water planning and responses to ‘simultaneously attend to the socioeconomic, cultural and political dimensions of water justice’ (Jackson & Barber, Citation2013, p. 3; see also Schlosberg, Citation2004, more broadly). Following these arguments, this tripartite framework can help conceptualize Indigenous water justice and local experiences of water colonialism.

Water colonialism

Indigenous water injustice occurs in the context that Robison et al. (Citation2018) term ‘water colonialism’. Water colonialism describes situations of past, present and ongoing acts, institutions, decision-making processes, physical interventions, discourses, narratives and paradigms that continue to marginalize and exclude Indigenous peoples. Although water colonialism as described by Robison et al. draws from observations across particular settler-colonial nations (the United States, Canada and Australia), evidence suggests that water colonialism is experienced in other colonial contexts, such as South Asia (D’Souza, Citation2006) and Malawi (Mathur & Mulwafu, Citation2018). Recent work also indicates that emerging norms of supra-national water governance perpetuate conditions of water colonialism (e.g., Taylor et al., Citation2019). Similarly, we might consider so-called ‘water grabbing’ processes, where extra-territorial actors appropriate water, as a form of water colonialism (Mehta et al., Citation2012).

Taking direction from settler-colonial theory (Wolfe, Citation1998), water colonialism describes an enduring political and economic order that perpetuates the expropriation of Indigenous water (Estes, Citation2019; Jackson, Citation2017a; Lynch et al., Citation2013; Marshall, Citation2017). Portrayals of contemporary water governance as politically and economically neutral work to obscure the ongoing role of the state and capital in producing and maintaining processes of colonial water expropriation (Boelens et al., Citation2018; Strakosch & Macoun, Citation2012; Wolfe, Citation1998). Herein, we aim to further develop understandings of Indigenous water justice and water colonialism by examining the case of water colonialism in the NSW portion of the MDB.

Case study context

Claims for water justice

There has been no formal treaty between the Australian government or its federal state and territory governments, and any First Nation of Australia. While First Nations’ ‘sovereignty […] has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown’ (Referendum Council, Citation2017), this sovereignty is not recognized politically or legally by the Australian state (Watson, Citation2012). This is evident in the colonial history of water governance and management. The history of colonial conquest could be written as a history of water dispossession, in which colonial occupation of First Nations’ territories followed the watercourses. Water governance and management systems served the imperial project of white nation-building and continue to be tailored to maximize the generation of economic benefit for agricultural capital and the settler-state (Berry & Jackson, Citation2018; Gibbs, Citation2009). In Australia’s south-east, governments supported and subsidized widespread construction of dams and weirs, causing significant environmental degradation and damage, with momentous consequences for First Nations peoples (Morgan, Citation2011; Weir, Citation2009).

Australia’s most productive agricultural region is the MDB (Grafton & Wheeler, Citation2018). The MDB incorporates the territories of more than 40 First Nations, and Indigenous people today comprise 5.3% of the area’s total population (ABS, Citation2017, Citation2018; MDBA, Citation2019). The MDB covers 14% of Australia’s landmass and traverses five state and territory jurisdictions, Queensland, NSW, Victoria, South Australia and the Australian Capital Territory. These state and territory governments are responsible for managing and controlling freshwater under the Australian Constitution.

This history of the MDB’s development exemplifies the exclusion of First Nations from water governance. Aboriginal peoples were denied riparian rights and access to statutory water entitlements under colonial, then state, laws (Berry & Jackson, Citation2018). Under colonial regimes, Aboriginal control of access to particular waters, such as through 19th-century reserves, tended to be relatively short-lived (Goodall, Citation1996). Governments largely ignored Aboriginal peoples when making decisions about water and when building the water-based economy, including when designing a water market in the late 20th century (McAvoy, Citation2006, Citation2008). Water trading commenced in parts of the MDB from the 1980s and accelerated in the 1990s (Grafton & Wheeler, Citation2018). While NSW Aboriginal land rights laws date from this time, governments had already over-allocated water-use entitlements beyond sustainable levels at the time land rights were introduced (Hartwig et al., Citation2020; Jackson, Citation2017a). Although the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) facilitates state recognition of Indigenous water rights and interests, interpretations remain narrow, encompassing only the right to water for personal, social, domestic and ‘non-consumptive’ cultural purposes (Hartwig et al., Citation2018). National water policy only accommodated this legal recognition a decade later in 2004 (Jackson, Citation2017a).

First Nation leaders, advocates and supporters have fought for the recognition and respect of their inherent rights and interests in land and waters in the MDB (Hemming et al., Citation2019, Citation2007; Jackson et al., Citation2021). The pursuit of water rights has seen First Nations alliances emerge first in the south with the Murray–Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations (MLDRIN) in 1998, followed by the Northern Basin Aboriginal Nations (NBAN) in 2011. These alliances now perform essential First Nations advocacy roles (Jackson et al., Citation2021). Coordination and advocacy have produced several First Nation-led policy initiatives, programmes and proposals including ‘cultural flows’ (Weir, Citation2009, Citation2017). Developed against a backdrop where water management was characterized by conflicts between agricultural and environmental needs (Mooney & Cullen, Citation2019; Morgan, Citation2011; Weir, Citation2009), this term was coined by Traditional Owners to assert their ‘distinct Indigenous identity and political status’ (Weir, Citation2009, p. 244). Cultural flows emphasize Aboriginal control and self-determination in water management decision-making processes and outcomes. The concept has gained some traction in Australian water management and research, although states still refuse to recognize First Nations peoples’ authority to manage and control water (O’Bryan, Citation2019; Weir, Citation2017).

Nevertheless, Australian governments have started acknowledging First Nations’ roles in water governance. An increased focus on consultation has had discernible procedural effects in some areas (Hemming et al., Citation2019; Jackson & Moggridge, Citation2019; Jackson et al., Citation2021; Mooney & Cullen, Citation2019). On the whole, however, state recognition remains limited and has not led to the kinds of political, economic and cultural outcomes sought by First Nations (Hartwig et al., Citation2018; Jackson et al., Citation2021; Marshall, Citation2017; McAvoy, Citation2006, Citation2008; Tan & Jackson, Citation2013). At the time of writing, a coalition of peak bodies representing Indigenous sector organizations is negotiating with state, territory and commonwealth governments to agree on targets for Indigenous control of interests in water (Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations (CATSIPO) & Australian Governments, Citation2020, p. 47). However, Aboriginal organizations continue to stress the need for deeper, more radical reforms to facilitate greater First Nation empowerment in MDB decision-making, and to redistribute water-use rights to Aboriginal peoples (Jackson & Moggridge, Citation2019; Mooney & Cullen, Citation2019).

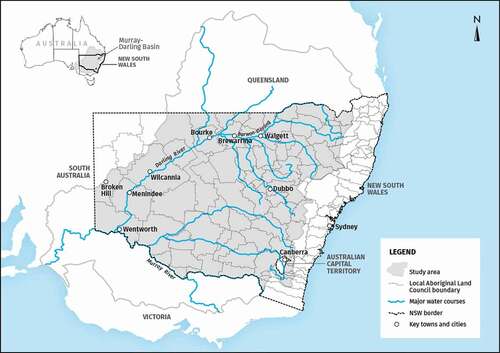

Indigenous demographic and socioeconomic geography

This paper focuses on the NSW portion of the MDB () for several reasons. First, analysis of recent census statistics indicates that 65.1% of the MDB’s Indigenous population resides in this area (ABS, Citation2017, Citation2018; MDBA, Citation2019). Second, 75% of Aboriginal-owned commercial water licences across Australia are held in NSW (Altman & Arthur, Citation2009), with most in the MDB portion of that state. Third, NSW was one of the first Australian jurisdictions to develop legislative, policy and programme responses to Aboriginal water claims, though with mixed success (e.g., Behrendt & Thompson, Citation2004; Hartwig et al., Citation2018; Jackson & Langton, Citation2012; McAvoy, Citation2006, Citation2008; Moggridge et al., Citation2019; Tan & Jackson, Citation2013; Taylor et al., Citation2016). does not attempt to depict First Nations’ territories. Such cartographic artefacts may exacerbate territorial conflicts among First Nations (Jackson, Citation2017b). Instead, it illustrates the boundaries of the 120 Local Aboriginal Land Councils (LALCs) incorporated under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW). LALCs hold lands restored to NSW Aboriginal groups based on place of residence rather than customary ownership. They also provide manifold social, community, governance, representative and/or cultural functions for Aboriginal communities and peoples in NSW (Norman, Citation2015).

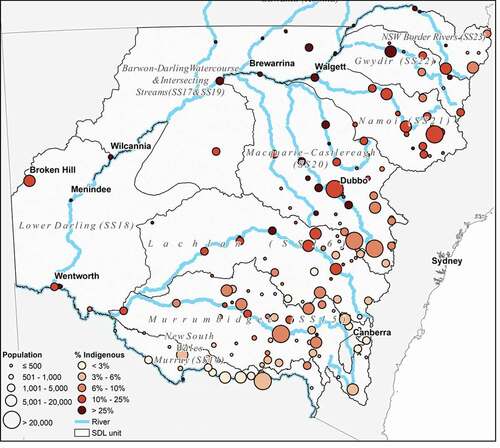

presents Indigenous and non-Indigenous population estimates for current water management units across the study area for the first time (called sustainable diversion limit (SDL) resource units). The Basin Plan 2012 sets extraction limits (called SDLs) for 29 surface water SDL resource unit management areas across the MDB, with 10 in the study area. This table shows that nearly 10% of residents in the study area identify as Indigenous. It also shows that the Indigenous population is unevenly distributed across SDL resource units. The largest Indigenous population of the MDB is in the Macquarie-Castlereagh SDL resource unit (25,542) which includes the regional centre Dubbo and many towns with smaller but sizable Indigenous populations such as Orange, Bathurst, Wellington and Coonamble. Several SDL resource units have much smaller Indigenous populations (3000–4000), including Lower Darling, NSW Border Rivers, NSW Murray and Intersecting Streams.

Table 1. Indigenous estimated residential population (ERP) by sustainable diversion limit (SDL) resource unit

The Indigenous population of the NSW portion of the MDB is growing remarkably rapidly. While around 50,000 Indigenous people lived in the study area in 2006 (ABS, ABARE & BRS, Citation2009), by 2016 the population had increased to 78,000. This compound growth rate of 4.5% per year is extreme by demographic standards. In contrast, the settler population of the study area is growing by only 0.2% per year. Because the drivers of Indigenous population growth in the MDB are poorly understood, with the Indigenous population increasing far more rapidly than can be accounted for by births and deaths alone, there is a great deal of uncertainty regarding the future Indigenous population of the MDB (Markham & Biddle, Citation2018b). If the remarkable 2006–16 growth rates continued, First Nations people would make up over 16% of the population in the study area in 2031.

shows SDL resource units, as well as cities, towns and discrete communities by size and Indigenous population share. It shows that while settlements in NSW generally tend to be located adjacent to rivers, this pattern is particularly evident among settlements where a high proportion of the population is Indigenous. Even in the most sparsely settled parts of NSW such as the north-west, Indigenous populations continue to occupy riverside towns and communities with declining non-Indigenous populations. This spatial demography, depicted in , informed our location selection for interviews.

Figure 2. Cities, towns and discrete communities in the New South Wales (NSW) portion of the Murray–Darling Basin (MDB), by population and proportion of population who are Indigenous

Indigenous peoples of the MDB have distinctly different socioeconomic status and demographic composition in comparison with the settler population, including lower rates of employment and lower household incomes (ABS, ABARE & BRS, Citation2009; Taylor & Biddle, Citation2004). The Indigenous population of the NSW portion of the MDB is relatively young (median of 22 years of age; ABS, Citation2017) and is disadvantaged economically, with a median gross weekly personal income for working age people of around A$450 per week and an unemployment rate of 18.5%. In north-western NSW, cash poverty rates were recorded at 37% in 2016 (Markham & Biddle, Citation2018a), making that region the poorest in the state.

Methods

This research draws together novel qualitative and quantitative data sets to help understand water colonialism for the study area. First, through two sets of interviews, we sought to understand the experiences, perspectives and strategies of 21 Traditional Owners whose Country includes the Barwon–Darling River system, an intermittent, dryland river running through north-western and western NSW. The first set of interviews were conducted with Traditional Owners from the Barkandji Nation in 2017 while visiting towns in western NSW (Wentworth, Broken Hill, Wilcannia and Menindee). Barkandji Traditional Owners’ voices have been prominent in media events focused on the health of the Darling River during recent years (Bates, Citation2017; Hartwig et al., Citation2018). Interviewees were identified through a snowballing strategy (Atkinson & Flint, Citation2001), beginning with the directors of the Barkandji Nation’s Prescribed Body Corporate (PBC), which is the corporation set up under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) to hold and manage native title in trust for all Barkandji native title holders. These interviews were semi-structured and sought opinions, perspectives and understandings of Indigenous water justice.

Traditional Owners from other Nations along the Barwon–Darling system, including Murrawarri, Ngemba and Ngiyampaa, have also expressed deep concerns for river health and water injustices. Our second set of interviews included Traditional Owners from a number of these Nations in response to an environmental flow event in the Barwon–Darling in 2018 (Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, Citation2018). Local Aboriginal water specialists were approached to identify community leaders in north-western NSW towns of Walgett, Bourke and Brewarrina to interview during this event. These interviews were more open ended, with interviewees asked about the environmental and social effects of the water releases. Their responses also revealed significant insights into Indigenous water justice.

For both sets of interviews, as many respondents as possible were interviewed while in the field and with the time and resources available, noting that some individuals referred to us could not be reached. Interviews were recorded and transcribed for thematic analysis, shaped by settler colonial theory and the tripartite justice framework. Interviews were conducted in accordance with the human ethics guidelines of Griffith University (GU reference numbers OTH/02/15/HREC and 2016/387), and we identify individuals in accordance with the consent they granted under these approved protocols.

We also describe a series of economic and environmental data related to Indigenous land and water holdings, as well as economic and demographic data. As Walter (Citation2016, Citation2018) argues, there are significant gaps in data holdings relating to Indigenous Australians, reflecting racialized power dynamics between First Nations peoples and government statistical agencies. Rarely are Indigenous priorities, including land and water rights, represented in statistical data. Consequently, we triangulate a range of data from different sources, and make the best estimates we can from the limited available data. These include data about Aboriginal collective water holdings (from Hartwig et al., Citation2020) and land holdings collated from various government sources in 2019, census data on Indigenous agricultural employment and business ownership in 2016, land-use data assembled from remotely sensed imagery acquired in 2017 (Department of Planning, Industry and Environment (DPIE), Citation2018) and regional water use and agricultural sales data estimated from the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) Rural Environment and Agricultural Commodities Survey (REACS) 2017–2018 (ABS, Citation2019a, Citation2019b). We furnish these data to illustrate the expropriation of water by settlers and the economic consequences of water colonialism.

Results

Insights from interviews with Traditional Owners

At the time of our interviews, western NSW was suffering from the worst drought on record, one that anthropogenic climate change exacerbated. Low rainfall and over-allocation of water to irrigation in the northern MDB over a much longer period has precipitated ecological collapse along the Barwon–Darling River, with severe social impacts particularly, though not exclusively, for Indigenous communities. The water issues that Traditional Owners raised during interviews are consistent with those detailed so far, especially the denial of rights, exclusion from decision-making and lack of recognition of jurisdiction.

Centring the river and its relations

All conversations shared a common ontological starting point: questions about water justice began with stories of the river and custodial relationships, not with the detached and abstract notion of ‘water resources’. These conversations centred the array of social, economic and cultural relationships with water that underpin First Nations peoples’ identities. For example, Barkandji PBC Director F, explained that:

The Paaka means ‘river’, and indji means ‘belonging to’. So, as a Barkandji person, I belong to the river. It’s Barkandji’s responsibility to look after the river. The Kurnu people up at Bourke, it’s up to them to make sure Nations further down have access to water.

Traditional Owners stressed relational values when they used terms and ideas such as ‘lifeblood’ or ‘mother’ to reference relationships that are vulnerable to disruption from infrastructure and over-use.

Frequently in these conversations, Traditional Owners referenced past activities carried out at local waterways, such as growing up along the river, fishing, celebrating, socializing and connecting with each other and with Country. Many also expressed a clear sense of nostalgia and grief for the loss of those experiences, as rivers, billabongs, wetlands or waterholes are now low or dry. Each time the river is denied water, it is another dispossession. We were told that lack of access to flowing water is not limited to the loss of what that water could be used for; it meant also that people cannot connect with traditions and practices and fulfil customary obligations, or pass them on and keep them alive. The harm the river has, and continues to, experience destabilizes the future – the loss of ceremonies past (and ceremonies to come) undermines social life and cultural practices and education. The ability to form quotidian, lived connections in daily habits of catching and eating fresh fish, swimming, taking children out on the water, is also damaged, and grieved.

Water dispossession and the fracturing of ceremonial and everyday relations threatens people’s lifeworlds. It is genocidal in effect. Brad Hardy from Brewarrina told us, ‘The river is like blood, without it, we die. We are the river people.’ Brewarrina is the site of the heritage-listed fish traps, an outstanding example of pre-European contact aquaculture (Bark et al., Citation2015; Pascoe, Citation2014). The fish traps are a complex arrangement of stone pens, channels and rock walls covering 400 m of the Barwon riverbed. Aboriginal people refer to the site as ‘Baiame’s Ngunnhu’ after the ancestral creator who made the traps during a time of major drought. The traps continue to be used today to catch fish in receding floodwaters. They are also an important historical inter-tribal meeting place for First Nations from the surrounding area, particularly the Ngemba people who are the custodians of the site, as well as the Murrawarri, Euahlayi, Weilwan, Ualari and Barranbinya people (Bark et al., Citation2015). Hardy, who leads cultural tours at the site, explained that it is ‘the oldest man-made structure’ in the world. In the mid-1960s the traps were ‘blown up to put a weir in’. Like others we interviewed, Brad viewed the degradation of the river as the colonial destruction of Indigenous lifeways. Settlers had ‘visions like the Americans – to hold water back and grow cotton’. The development of the region and extraction of its flows of water brought incalculable loss for the Aboriginal economy: ‘Our society wasn’t greedy, we built in the backwater to catch some [fish], not all. […] Everything our people needed was found along this stretch of river, before cotton.’

Poor water quality and its web of impacts

Upstream at Walgett, Doreen Peters also reminisced about a time before cotton when the river was ‘clean’ and the fish plentiful. Families would meet on the river where they would fish and pass on knowledge to younger generations. ‘Cotton has taken most of the water from the river. The town of Walgett could die from not having a good, or clean, river.’ When we interviewed Doreen, Walgett residents could no longer draw water from the river; they were reliant on groundwater from the Great Artesian Basin. Its salt content was so high that the Aboriginal Medical Service was recommending that people buy bottled water. Reliance on bottled water was commonplace along the Barwon–Darling River until recently (), despite the low incomes of many of the Aboriginal residents. At Bourke, Robert Knight explained that he spent A$50 a month on bottled water because he ‘doesn’t drink water out of the tap’. He is deterred by the muddy taste of the river water and the existence of a cotton gin ‘right here near town’ (with aerial crop spraying). Jason Ford at Brewarrina said that, ‘we’re the poorest people in society and we can’t use this water’. Barkandji interviewees also reflected on the economic strain of having to purchase drinking water due to the health risks associated with poor quality of available water options.

Figure 3. Towns such as Menindee, which have a high Indigenous population, have recently relied on purchased and/or donated bottled water

In describing the social impacts, the people we interviewed saw continuities between dispossession and trauma, between river health, human health and social vulnerabilities. Barkandji Person B said:

When there’s no water, the crime rate goes up and when there’s water, that relieves the community and the crime rate goes down. The river is a source of recreation for us – people go camping, fishing, swimming and events are put on when there’s water in the river. When the water’s gone, there’s a real mental impact on our community and that’s when crime goes up.

Those we interviewed felt the impact of water colonialism at the psychosocial level. Several leaders referred to the trauma their communities have experienced. Ike (Isaac) Gordon, a pastor from Brewarrina, has long drawn the association between community health and river health. He explained that, ‘it’s our veins, that’s why we live here, because of the river’. Since the 1990s, the water level has dropped 2 m below the normal bank and the river has stopped running, which is an occurrence he has only seen twice in his 55 years. ‘It’s greed that killed our river, pure greed.’ Ike described graphs presented at public health meetings that map the coincidental deterioration in river flows and the very high death rate of his people. He said, ‘what makes me sick is when our rivers are sick. They are wasting the water, flooding the fields […] you’re slowly killing us […] Everything we had to help us cope has been taken away from us’. River restoration is a cultural imperative because:

the river is a source of healing. I see a lot of sadness, I do funerals as a pastor. We’re faced with grief and sadness, so much. […] The river is a place where we find so much peace. It helps.

For Robert Knight, when the river is running at Bourke:

it builds excitement in us because it is a time when we can go fishing. And when the river rises like this, people are always on the river. So it brings food, recreation for our people, helps feed families. Our people are always on the river.

Reparations, redistribution and compensation

As is reported elsewhere in the same region (e.g., Bark et al., Citation2015; Goodall, Citation2008; Muir et al., Citation2010), it is clear that Aboriginal leaders have thoughtfully considered the role of ecological and hydrological processes in sustaining their life, livelihoods, cultural practices and well-being. Principles or norms of justice infused the interviewees’ commentary, and the severe distributional impacts of water resource development were acknowledged as central to current water justice claims. According to a Paakindji man interviewed:

Water justice means reclaiming back some of the resources that were totally ours. The allocation has been over 100% for the Darling due to some of the agriculture practices further upstream, which means that our people have not had access, or any say in [the management of] our cultural heritage.

Barkandji PBC Director E said:

There’s hardly any water at the best of times so I don’t know how they’re going to survive in the future if they’ve still got their cotton plantations there, big ones! Must be generating millions of dollars, but the Aboriginal people don’t see any of it and it’s our rivers that they’re raping.

Barkandji Person B and several others we interviewed regarded financial compensation as a necessary form of reparation for the damage done to the river and to Aboriginal peoples:

Well, I think for every Aboriginal person that lives on our waterways where they’ve been destroyed, government owes us each so many gigalitres of water. Why? Because of our cultural flows and because we haven’t been given access to those cultural flows in this national disaster. No one has cared about our rights! […] It could be part of a royalty deal – that every Aboriginal person who lives near or depends on the waterways should be entitled in this way!

A Barkandji Native Title Holder pointed to the profound power imbalance that Aboriginal people face when negotiating over water:

They basically told us at the [government-facilitated groundwater consultation] session a couple of weeks ago that the extraction of water is going to go ahead anyway, so if we don’t negotiate and get involved, they’re going to go and do it anyway! My point for being involved is for them to know that we don’t support it, even if they go ahead with it. We have to look at social justice for us, for our cultural rights and for the cultural identity of our generation, and the generations to come after us. If industry is going to get money and benefit out of our resources, that’s not fair! I don’t want to just negotiate for site monitoring opportunities and a small bit of employment for our people. We want some decent compensation. […] I live in high hopes that we don’t just get consultation, but we get to negotiate.

In addition to claims for financial reparations, several people stressed the possibility of restoration enabled by water rights for Aboriginal Nations. According to Barkandji PBC Director D:

it’d be good if we had cultural flows coming down the Darling. Those cultural flows would go right through, right into Wentworth and into Lake Victoria, and then some of that water would be stored at Menindee. […] We want our cultural flows.

Beyond redistribution, political participation and jurisdiction to exercise management rights is integral to water justice. Even though the Barkandji have received legal recognition through the native title framework, they have little control over water (Bates, Citation2017; Hartwig et al., Citation2018). Barkandji PBC Director D explained that, ‘the Darling is our lifeblood. Without that, we are finished. So water justice is nothing, it’s just on a piece of paper until that party comes and sits and talks with us, and then there’s justice’. Barkandji Traditional Owners see state water managers overruling, dismissing or ignoring their jurisdiction as governments endorse and govern in favour of powerful cotton and mining industries. Consultation about water management does not equate to decision-making power: ‘We’ve been going to all these meetings, but we still don’t have a final say’ (Barkandji community member D).

Interviewees understood water justice to be multidimensional, encompassing more than just the distributional realm. It entails the capacity to share water with Country, to ensure the continuity of cultural life, and have a degree of meaningful control over water governance. Barkandji Person C’s reflections summarize these perspectives:

Water justice to me is getting our fair share of good quality water, and to have our rights protected in law and recognised. Water justice would be to ensure river flows aren’t compromised for irrigation. Water justice is to ensure our rivers are healthy, not just have water flowing through them, but are actually healthy. Water justice is looking after our native species and aquatic species. Water justice is being able to go to the river and catch a feed. Water justice is practicing culture. Water justice is having a feeling of connection. Water justice is being able to share that water. Water justice is having a right to decide how we manage water. Water justice is having water security and having environmental and cultural flows protected. Those things are what water justice is to me.

Insights from economic and environmental data

Data relating to land and water holdings and water-related socioeconomic benefits reveal the current inequitable distribution of the commercial economic outcomes of water colonialism. We focus on agriculture because in the MDB, agriculture is the primary commercial use of water. Consequently, understanding the distribution of water’s economic benefit between First Nations people and settlers requires an engagement with the political economy of agricultural land ownership. Accordingly, in this section we analyse land ownership and water use jointly. We present these analyses not to imply that Aboriginal land-holders should use land and water in the same manner as settler agriculturalists, but rather to demonstrate the economic imperative underpinning continued colonial control of water.

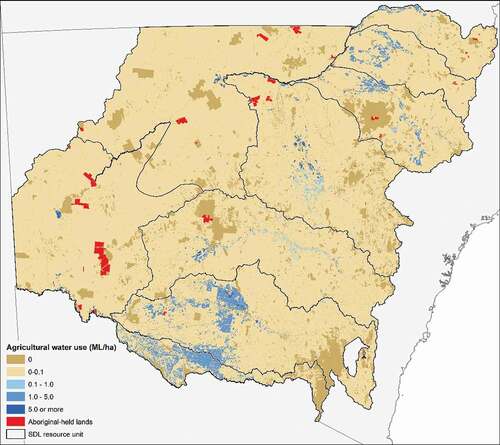

maps Aboriginal-held land alongside agricultural water use across the study area. This Aboriginal-held land includes claims granted through the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW), properties purchased for Aboriginal entities by the Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation (ILSC), protected areas returned to Aboriginal groups under Schedule 14 of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW), and lands where courts have determined the existence of exclusive possession native title. (There are other lands held by LALCs or the NSW Aboriginal Land Council in this area which have been acquired through market purchases or bequests, but these lands are not included because this information is not publicly available.) also demonstrates that for most Aboriginal-held lands, particularly the largest properties, the marginal economic productivity of water is likely to be low. Little of the Aboriginal land estate is suitable for profitable irrigated agriculture (Holmes, Citation2006). In some cases, leaseback arrangements, zoning and other restrictions also prevent agricultural uses of Aboriginal landholdings (Behrendt, Citation2011; Norman, Citation2015). Apart from properties purchased by the ILSC, this is largely by design. These restitution mechanisms were intended to only return those lands that were surplus to the requirements of settler capitalism (Altman & Markham, Citation2015; Norman, Citation2015).

Figure 4. Aboriginal lands (held collectively) and water used for agriculture across the study area

In some cases, returned land also included water entitlements (Hartwig et al., Citation2020). presents recent estimates of the total land and water holdings acquired through these arrangements by Aboriginal entities, noting that some Aboriginal individuals own agricultural properties and water entitlements, but land title and water registers prevent their identification (Altman & Arthur, Citation2009; Altman & Markham, Citation2015). Until now, this information has not been presented in a format that corresponds with current water management geographies. It shows that Aboriginal entities hold only 0.75% of land and 0.22% of water holdings across the study area, despite the fact that Indigenous people constitute 9.3% of the total population. Here we do not estimate the value of the land holdings, although Hartwig (Citation2020) calculated that the NSW–MDB Aboriginal water holdings were valued at approximately A$16.5 million, or about 0.1% of the value of the entire MDB’s water entitlement market in 2015–16.

Table 2. Aboriginal collective water and land holdings by sustainable diversion limit (SDL) resource units

shows considerable variability in the size and proportions of Aboriginal collective land and water holdings within and across the 10 catchments. Although Aboriginal water holdings are largest by volume in the NSW Murray and Murrumbidgee SDL resource units, very little land has been returned there. Indeed, statutory land rights restitution mechanisms have been no more successful in aggregate than the more ad-hoc water holdings return processes. Despite land rights restitution measures and the legal recognition of native title, Aboriginal entities in the study area hold a tiny share of water and land relative to their population size (). In an absolute sense, these land and water holdings are miniscule.

Aboriginal exclusion from holding land and water as factors of production correlates with low levels of Aboriginal private benefit from agricultural economies (). shows the numbers of Indigenous agricultural businesses and agricultural employees by catchment. Unlike and that describe Aboriginal collective land holdings, Indigenous agricultural businesses in are privately owned. Estimates of the Indigenous people who work as employees in agricultural industries are also included in .

Table 3. Indigenous agricultural business ownership and employment by sustainable diversion limit (SDL) resource unit, 2016

Table 4. Estimated irrigated agricultural production by Aboriginal land ownership across the study area, 2017–18

Despite making up 9.3% of the population in the NSW portion of the MDB, Indigenous people own just 0.5% of its agricultural businesses. This reflects both the initial wave of colonial land expropriation and the subsequent history of the theft of Aboriginal agricultural land holdings and reserves (Goodall, Citation1996). Compounding this initial dispossession, discriminatory laws made significant Aboriginal land ownership and capital accumulation impossible for many decades.

Indigenous people form a larger proportion of the employed agricultural workforce, at 3.5%. This is perhaps unsurprising given the historical nature of Aboriginal employment in agricultural industries (Keen, Citation2010; Sharp & Tatz, Citation1966). Yet agricultural employment in Australia is itself in decline (Rosewarne, Citation2019), forestalling its potential as a future source of work for a rapidly growing Indigenous population.

attributes irrigated agriculture revenue in the study area to Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal owners based on land use and NRM region, in proportion to Aboriginal landholdings in each land-use-by-NRM category. Aboriginal peoples appear to receive only a tiny fraction of total revenue generated from irrigated agriculture. Aboriginal people are estimated to receive A$2.4 million of the A$3.4 billion of irrigated agricultural revenue accounted for in (less than 0.1%). While this estimate is indicative only, it demonstrates the economic consequences of water colonialism. The economic structure of water colonialism – selective restitution after dispossession – is such that Aboriginal people accrue almost no income from irrigated agriculture.

Aboriginal people currently receive negligible benefits from irrigation and agricultural activities on their territories. The ongoing colonial expropriation of water benefits is at least partly linked to the distribution, quantity and quality of Aboriginal land and water holdings, itself a direct consequence of historical patterns of land and water allocation and usage, as well as selective approaches of the state to restitution (Hartwig et al., Citation2020; Jackson, Citation2017a; Norman, Citation2015; Weir, Citation2009). These analyses demonstrate that the return of just land or just water rights in isolation is insufficient for economic justice. Both are inextricably linked.

Discussion

The case study reveals persistent and multidimensional water injustice for Aboriginal peoples. We have demonstrated that settlers dominate Aboriginal peoples’ waters, thereby expropriating economic resources, subverting Aboriginal political control and damaging lifeways. We characterize this condition as water colonialism. Traditional Owners described the oppressive conditions and distressing experiences that they and their communities endure as they confront misrecognition, disrespect and exclusion from the political and cultural processes that underpin the governance of water. Our analysis of the current distribution of collective Aboriginal-held land and water rights, together with associated economic benefits from water-intensive agricultural industries enjoyed predominantly by non-Aboriginal people, shows the extent of the expropriation of water and water-derived wealth from Aboriginal peoples in south-east Australia. Together, these findings point to the enduring colonial structures that favour settler rights and interests, which deny the illegitimate foundations of Australia’s agricultural wealth and the rights and interests of First Nations to share in the wealth generated by water use.

A fourth dimension of justice: the socio-ecological

Alongside representation, recognition and redistribution, our analysis of the local, grounded and relational conceptions of water justice conceived by Indigenous participants requires the addition of a fourth dimension. Interviewees frequently emphasized reciprocal relationships with Country and with other people across time and space (McGregor, Citation2015). Many also reflected on past activities relating to their waterways, such as growing up along the river, fishing, celebrating and connecting with those places, its non-human inhabitants and with other people. However, over-extraction (particularly upstream), the construction and operation of water infrastructure, and other state-sanctioned water management policies have caused significant impacts to the health and survival of these water relations and have threatened drinking water supplies. Many interviewees expressed a clear sense of loss for those activities that can no longer take place and described a range of resulting harms that are not being attended to or cannot be ameliorated by, for example, the importation of bottled water. As access to a healthy and flowing river diminishes, this dispossession affects Traditional Owners’ independence, and abilities to sustain themselves, connect with and pass on customs and practices (see also MDBA, Citation2016b; Weir, Citation2009, Citation2017).

These relational conceptions of (water) justice reflect Aboriginal philosophy (e.g., Graham, Citation2014) and align with Yaka’s (Citation2019, p. 356) articulation of a ‘not-yet-captured’ dimension of justice which she terms the ‘socio-ecological’ realm. Yaka develops this new justice dimension at length in response to new kinds of injustices arising from the neoliberal marketization of environmental commons – specifically, empirical insights from community struggles against hydropower plants in Turkey. She acknowledges that this dimension is of relevance to the struggles of Indigenous people for environmental justice globally. Indeed, it strikingly resonates with the conceptions of justice articulated by Traditional Owners we interviewed but which are obscured or neglected in Fraser’s framework. That is, this dimension of justice frames the intrinsic relationality of human and non-human life as a matter of justice and, therefore, reflects the situated ecological embeddedness of human existence and its (water) governance decisions (Yaka, Citation2019; see also Boelens et al., Citation2018). Justice struggles in this dimension focus on preserving – or as we find, improving or restoring – a locally defined and understood ‘socio-ecological existence, [which is] the intrinsic relationship people establish with the river’ (Yaka, Citation2019, p. 359).

Recent advocacy from Aboriginal representative organizations, and the actions of some within the water sector, is effecting modest change towards improving socio-ecological relationships. Such change is reflected in the growing interest in and support for the notion of ‘cultural flows’ and in policy and procedural changes in water agencies including the Murray–Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) and the office of the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder (Jackson & Nias, Citation2019; Mooney & Cullen, Citation2019). In response to the major shift in policy towards restoring river health in the MDB, First Nations water alliances are developing methodologies designed to elevate Aboriginal objectives in water planning, document water related values and influence waterway management (Mooney & Cullen, Citation2019). Water agencies have tended to publicly support such initiatives and some have funded programmes to implement ‘cultural flows’ through water planning and environmental water management mechanisms (or at least to include First Nations environmental aspirations) (e.g., MDBA, Citation2020; Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Citation2019).

Politics, power, and (lack of) representation and recognition

While these ‘cultural flow’ advances are significant and important, they remain limited by the continued exclusion of Aboriginal peoples and poor recognition of Aboriginal decision-making authority and reciprocal ontologies by state-led water governance and management processes. Data show that in the case study region, Aboriginal peoples remain excluded from political and decision-making processes about water, even when they have successfully struggled for legal recognition (Bates, Citation2017; Hartwig et al., Citation2018). Participants in our study argued that a crucial step towards water justice would be for decision-makers to come to Country, sit down and talk with, and listen to, Traditional Owners. That first step was rarely taken, and when consultation did occur, it was considered tokenistic and the outcomes predetermined. The state retains significant control over who can participate and have power, and who, how and what to recognize. Recognition alone does not necessarily result in more inclusive or collaborative decision-making processes (Jackson, Citation2018b).

The concerns and insights canvassed so far are well documented in existing literature and community statements. For example, socio-ecological relations and concerns for Country and people and the interconnection of Indigenous exclusion, misrecognition and misrepresentation in contemporary water governance in the MDB are examined particularly by Weir (Citation2009), but also other scholars and advocates (e.g., Bark et al., Citation2015; Goodall, Citation2008; Hartwig et al., Citation2018; Jackson & Langton, Citation2012; Muir et al., Citation2010; Shillingsworth, Citation2019). By comparison, there is far less available evidence and analysis of the distributional dimension of Aboriginal peoples’ justice claims in this area. Undoubtedly, our findings show that all these interconnected and interdependent dimensions of justice need much further work and attention to move towards water justice for First Nations. Nonetheless, redistribution concerns are increasingly central to First Nations’ water claims and self-determination in the MDB (Jackson et al., Citation2021) and accordingly warrant concerted attention.

Redistribution: dispossession and maldistribution

Until very recently, governments have consistently ignored calls to return water to Aboriginal peoples (Marshall, Citation2017; McAvoy, Citation2006). Aboriginal-specific water access options that are available in the case area, such as native title and Indigenous-specific entitlements, have proven difficult to secure, offer minimal water access and preclude commercial use options (Hartwig et al., Citation2018; Jackson & Langton, Citation2012; Tan & Jackson, Citation2013). More recently, governments appear to be somewhat more open to redistributing water to First Nations. Options for reallocation, however, are defined from within the existing marketized water access framework, and so far have not impinged on the rights of ‘existing’ (i.e., non-Aboriginal) water rights holders. By prioritizing existing rights holders within a water market, governments are likely to continue to ignore the pre-existing rights of Aboriginal people to water, regardless of changes in rhetoric.

A key recent reparation response here has taken the form of allocation of state funds for First Nations to purchase water entitlements. In 2018, the federal government took a small step in this direction, committing A$40 million to purchase water entitlements for Aboriginal people across the MDB. The effect of these relatively small funds on water distributions remains in question, however, especially given that the quantum represents a mere 0.2% of the market value of all MDB water entitlements (in 2016). For comparison, Aboriginal advocates argued 20 years ago, when water was less costly, that A$250 million was needed to redistribute water more equitably across NSW alone (McAvoy, Citation2008). The reliability and security of water access under purchased water entitlements, which can affect the material benefits derived from water, is another key concern (Hartwig et al., Citation2020). To date, no water entitlements have been purchased with these committed funds.

Achieving Indigenous water justice requires more than the redistribution of water rights; our analysis shows that it requires water rights restitution be also accompanied by sufficient land restitution. Although government land restitution and purchasing programmes have returned a small amount of land, most is suitable for grazing rather than more intensive land uses (). Indeed, a series of state decisions and (in)actions have meant that the quality of most collective Aboriginal landholdings is ‘less productive’ in a capitalist sense, because agricultural land is largely excluded from restitution schemes (Behrendt, Citation2011; Goodall, Citation1996; Hartwig et al., Citation2020; Norman, Citation2015). The effect on Aboriginal water access is twofold. First, the amount of water returned with such land has been very limited in volume (Hartwig et al., Citation2020). Second, the economic uses available to Aboriginal water holders are likely to attract lower returns than irrigated agriculture. While Aboriginal Traditional Owners and water holders have diverse aspirations for water use that transcend the narrowly defined ‘economic’ (Weir, Citation2009), some may choose to engage in irrigation if that option were available to them.

However, even the redistribution of water and suitable agricultural land may not be enough to ensure economic prosperity. The increasingly centralized and capital-intensive nature of agricultural industries pose a further barrier to economic redistribution through the market, requiring Aboriginal entrants to the market to have greater and greater quantities of capital simply to compete. While this logic was recognized early in the Aboriginal land rights movement, when campaigners sought reparations as well as land returns in order to fund economic development (e.g., Newfong, Citation2014), such demands have seldom been adequately met. Opting-out of the market entirely is not always an option for water holders. Landholding involves considerable ongoing costs, and so unprofitable uses of water may become financially unsustainable over the medium to long term, as the recent and substantial losses of Aboriginal water holdings documented by Hartwig et al. (Citation2020) demonstrate. Thus, the coercive force of competition will require Aboriginal water holders to maximize their economically productive use of water or risk insolvency. Consequently, although First Nation water holders may view water holistically, the settler-state and market impose pressure to generate an economic return for water use, regardless of Aboriginal water holders’ aspirations.

So far, our analysis accords with the narrow neoclassical definitions of productivity, value and so on, itself part of the operation of water colonialism in economic policy and water governance. A more critical application of the term ‘productive’ is warranted (Altman, Citation2009; Sangha et al., Citation2015; Stoeckl et al., Citation2013). Alternative land uses such as conservation and/or Caring for Country activities are restorative and productive because, in conjunction with targeted ecological and cultural benefits and outcomes, they employ Aboriginal people and produce a suite of other social and/or economic benefits (Barber & Jackson, Citation2017). Such activities can include the application of water, as seen in places within the case area (and elsewhere in the MDB) (Jackson & Nias, Citation2019; The Nature Conservancy, Citation2020) and may improve socio-ecological relationships.

In the northern and western parts of the study area, environmental watering activities have been more limited than the south. Nonetheless, in an MDBA (Citation2016a) survey of this area, a large portion of employed Aboriginal respondents saw their employment is ‘water dependent’, including Caring for Country activities, showing that these projects can be economically productive even in the reductive framework of national statistics (Taylor & Biddle, Citation2004). However, it is important that alternative approaches to managing the environment do not inadvertently reproduce settler-colonial frameworks by accepting its terms and metrics. Water justice for Indigenous peoples means remaking those systems, not performing well under them or being merely recognized by them.

We suggest, therefore, that the socioeconomic dimension of Indigenous water justice and the (re)distribution of water resources to Aboriginal people needs to attend to two truths. First, Indigenous water injustice entails the denial of a fair share in the benefits and/or wealth produced from access to water. Second, Indigenous water injustice also entails the loss or appropriation of what was once controlled by Indigenous peoples, ‘not as property but as commons’ (Yaka, Citation2019, p. 357). The distribution dimension of Indigenous water justice is therefore first a case of dispossession, as well as maldistribution, of both water and land. Government responses to this justice dimension show that the Australian settler-state is yet to grapple with these colonial legacies.

Water colonialism and new formations

The results confirm that water colonialism is not a mere legacy issue. In the more recent water management era, return of land without water or capital to First Nations people is playing out in new ways, as anticipated by Jackson (Citation2017a). For instance, in 2013 the federal and NSW governments purchased 19 properties and associated water-extraction entitlements from private irrigators as a significant water-saving project. With the assistance of The Nature Conservancy, the ILSC and the Wyss Foundation Campaign for Nature, this 87,816 ha area – now named Gayini, the Nari Nari word for water – was handed back to First Nation ownership in late 2019, but without any water rights. Instead, the rights were transferred to the federal government for environmental purposes (The Nature Conservancy, Citation2020). Although the Aboriginal owners, the Nari Nari Tribal Council, are still able to achieve their desired outcomes by partnering with other land and water managers to restore wetlands and landscapes with government- and privately held environmental water (Jackson & Nias, Citation2019), they do not hold this water themselves. This example, among others, demonstrates that water colonialism is a constitutive element of today’s water (and land) governance structures and is perpetually being remade in new forms, creating new legacies.

Other new legacies are now in the making because of water and agricultural reforms. Australia has seen a long-run rationalization within the agricultural industries towards dominance by larger farms (Larder et al., Citation2017; Rosewarne, Citation2019). Under this arrangement, farming becomes increasingly capital intensive and maintaining the viability of smaller and/or marginal farms is increasingly difficult (Holmes, Citation2006). Structural reforms targeted at maximizing water-use efficiencies through reallocation of scarce water resources via the water market (Grafton & Wheeler, Citation2018) and increasing assetization of water rights (Larder et al., Citation2017) contributes to water market appreciation, further adding to this dynamic.Footnote2 This dynamic is amplified when available water allocations shrink because of water recovery for environmental purposes and/or declining mean rainfall and downstream flows (Interim Inspector-General of MDB Water Resources, Citation2020).

These factors and tendencies perpetuate past colonial injustices in two ways. First, they increase and intensify the pressure to alienate Aboriginal peoples’ already (limited) water and land rights. Aboriginal people have been deprived of the ability to accumulate capital and wealth that makes operating financially ‘viable’ properties – as defined in accordance with narrow neoclassical economics and required by settler-colonial land rights legislation or deed of grant – extremely difficult. In some cases, these challenges and difficulties have led to forced liquidation of Indigenous organizations and another round of losses as land and water are removed from the control of communities (Hartwig et al., Citation2020; Jopson, Citation2015). Second, they make securing new land and water rights more expensive and difficult for Aboriginal people. Thus, Aboriginal people remain largely locked out of accessing economic benefits from agricultural land and water use. We anticipate that the patterns of water colonialism described here will be no different in other parts of south-eastern Australia, including other parts of the MDB, given that Aboriginal land and water dispossession and holding patterns and Indigenous socioeconomic conditions are fairly consistent across this area (Altman & Arthur, Citation2009; Altman & Markham, Citation2015; Taylor & Biddle, Citation2004).

At a larger scale, and by virtue of the interconnections of the dimensions of justice, these factors work to centralize power and authority among those with economic power (Boelens et al., Citation2018), such as cotton farmers and larger irrigation bodies. Notwithstanding emerging models that provide some recognition of the legitimacy of Indigenous governance (Jackson et al., Citation2021), data from this study show that local Aboriginal leaders and Traditional Owners remain largely excluded from mainstream water governance, and opportunities to affirm their authority remain limited.

Conclusions

This paper presents First Nations’ voices from north-western NSW alongside economic and environmental data in a novel form that corresponds with new water management geographies configured under the MDB Plan. We show that recent decisions and ongoing governance structures continue to dispossess Indigenous people of water, not only as a resource (and all that it supports ecologically and economically) but also as a vital constituent of territory and of hydro-social relations. First Nations peoples in north-western NSW and the MDB more broadly remain unable to exercise rights to make decisions about water use and management (O’Bryan, Citation2019), notwithstanding recent efforts by governments to recognize their culturally distinct relationships with water. Overall, this case study illuminates specific ways that persistent water colonialism jeopardizes Indigenous identities, well-being, and livelihoods and forecloses opportunities for self-determination. Our findings reveal that land access and ownership are inextricably linked to water justice, and that water justice is central to, but also inseparable from, broader notions of Indigenous justice and self-determination.

This paper also identifies a paucity of information on the social and economic conditions and experiences of MDB Aboriginal communities relating to daily water access and broader water governance and reforms. To this end, more precise and up-to-date knowledge of the situations faced by Indigenous communities could benefit those communities and local policy-makers. Following Walter’s (Citation2018) call, such data should be designed, owned and controlled by Indigenous people in order to reflect not just the complexities of Indigenous structural disadvantage but also the diverse cultures, narratives, geographies, goals and aspirations of Indigenous peoples. Current data holdings lack Indigenous identifiers for the most part and also reflect the categories of dominant settler agricultural practices and capitalist economic organization. In the area of study specifically, for example, more could be known about the multidimensional costs borne by Aboriginal people in accessing domestic water supplies (i.e., financial, health, experiential, etc.), how Aboriginal landholders currently use and benefit from water and their aspirations regarding water. Such insights are crucial for developing transformative responses that reflect First Nation peoples’ diverse water-related social and economic experiences and their struggles for justice.

This paper offers important insights for other Indigenous water in/justice and water colonialism contexts, particularly where water is over-allocated. While Indigenous perspectives about water and water justice are locally embedded and heterogeneous, the centrality of water to Indigenous peoples’ identities and their relationships to people and place across space and time is a common feature. Therefore, to adequately capture these crucial perspectives, we emphasize that frameworks for interpreting and understanding Indigenous water in/justice struggles must include Aboriginal notions of relationality as part of a ‘socio-ecological’ dimension; a realm that is not well encapsulated by Fraser’s tripartite justice framework. Future research should seek to examine further its suitability for better understanding and conceptualizing Indigenous water justice in other places and contexts.

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply grateful to the Traditional Owners interviewed during the course of this research, as well as Uncle Gerald Quayle, Uncle Badger Bates and Derek Hardman for their encouragement after reviewing an earlier draft of the paper. Thanks also to Brad Moggridge, Jason Wilson and Phil Duncan for advice on interviewees and community contacts. The authors extend their appreciation to the two anonymous reviewers whose helpful suggestions and comments improved the quality of this paper, as well as the editors of this special issue.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Consistent with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, we use the term ‘Indigenous’ when referring to those communities, peoples and nations that have a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, and who consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing on those territories, or parts of them. In Australia, a range of terms is used, including Indigenous, Aboriginal and, more recently, First Nations. The last two tend to be preferred locally in the study area (Jackson et al., Citation2021), and we use the same terminology here. ‘Traditional Owner’ is another term often used in Australia that we use, one that describes Aboriginal people who have particular responsibilities towards their custodial territories inherited through their ancestors (Weir, Citation2009). The exception is when describing demographic and socioeconomic data that aggregate those who identify as Aboriginal with those who identify as Torres Strait Islander. In this case, we use the term ‘Indigenous’. Further, ‘Country’, as used in this paper, is the Aboriginal English term that represents Aboriginal peoples’ holistic and sacred understandings of their territories, including land and water, and their relations with them (Rose, Citation1996).

2. Of course, the valorization of water entitlements can also benefit those Indigenous organizations that hold water entitlements. Hartwig (Citation2020) provides a comprehensive examination of Aboriginal water trades in the study area and shows that some Aboriginal organizations do engage in temporary trades and, in doing so, obtain funds for local activities but under constrained circumstances.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics). (2017). 2016 Census – Counting persons, place of usual residence. Census TableBuilder.