ABSTRACT

This paper analyses continuity and change in flood risk management policies in Italy between 1952 and 2020. By using the politicized institutional analysis and development (IAD) framework, we systematically analyse the interplay between discursive, institutional and contextual factors to explain policy continuity and change. Italian flood risk management has traditionally been state-centred and focused on flood protection infrastructure for hazard reduction. Although shock events and European Union directives have been triggers for change, the policy shift towards a risk-based approach has been hampered by strong centralism and a hostile attitude towards the differentiation of rules and practices.

Introduction

Flooding is a ‘chronic and costly risk’ for cities and local communities (Witting, Citation2017, p. 251), and flood risk governance has gained increasing importance over the past decades (Alexander et al., Citation2016; Jabareen, Citation2013; Kundzewicz et al., Citation2018). The concept of risk governance refers to ‘the totality of actors, rules, conventions, processes, and mechanisms concerned with how relevant risk information is collected, analyzed, and communicated, and how regulatory decisions are taken’ (Renn et al., Citation2011, p. 233). Flood risk governance arrangements are specifically defined as ‘the actor networks, rules, resources, discourses and multi-level coordination mechanisms through which flood risk management is pursued’ (Alexander et al., Citation2016, p. 4).

Flood risk is a function of the chance (or probability) of a flooding event and the impacts (or consequences) associated with the event (Sayers et al., Citation2002). Flood risk mitigation can thus be achieved by implementing flood probability reduction measures (hazard reduction), or by limiting the consequences of flooding events through enhancing community coping capacity (vulnerability reduction) and limiting floodplain occupancy (exposure reduction) (De Moel et al., Citation2009; Oosterberg et al., Citation2005). Compared with the standards-based approach, wherein the main focus is on ‘the severity of the load that a particular flood defence is expected to withstand’, the risk-based approach stresses the importance of addressing both the probability and consequences of floods (Sayers et al., Citation2002, p. 37).

Italy is affected by floods annually. Next to the entity of weather events, often not exceptional in their intensity, a long-lasting public debate questions the existing governance arrangements and criticizes the lack of a comprehensive approach to flood risk management. Italian flood risk policies have traditionally focused on flood probability reduction (hazard reduction) through flood control infrastructure (Vitale et al., Citation2020). Poorly managed urban development and floodplain occupancy have exacerbated the exposure and vulnerability to floods. Therefore, more recently, attempts have been made to diversify flood risk management strategies and realize a shift towards a risk-based approach (Vitale & Meijerink, Citation2021). In this study, we aim to better understand the evolution of Italian flood risk policies, analysing the extent to which these policies have changed or are characterized by continuity, and why.

The main research question addressed in this study is: How can we understand continuity and change in flood risk management policies in Italy between 1952 and 2020? To answer this question, we draw upon the politicized institutional analysis and development (IAD) framework by Clement (Citation2008, Citation2010), which builds on Ostrom’s (Citation1986, Citation1990, Citation2005, Citation2007) IAD framework. The IAD framework by Ostrom helps to analyse and test the hypotheses about behaviour in diverse situations at multiple levels, and analyses how rules, physical and material conditions, and attributes of the community affect the structure of action arenas, patterns of interaction and outcomes. The politicized IAD by Clement (Citation2008, Citation2010) adds two more external variables to the framework: politico-economic context and discourses. To gain a better understanding of continuity and change in flood risk policies in Italy, we systematically scrutinized the five external variables potentially affecting the national action arena, patterns of interaction and policy outcomes; these variables are physical–material conditions, politico-economic context, discourses, attributes of the community and rules-in-use. The advantage of this framework is that it does not prioritize material, political, discursive or institutional variables, but allows for a broader exploration of all the potentially relevant conditions.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The next section introduces the theoretical perspective underpinning this research. The third section provides details on the methodology used. The fourth section presents the findings of our longitudinal analysis of flood risk policies in Italy between 1952 and 2020. The fifth section gives the main conclusions and engages in a broader discussion.

The politicized institutional analysis and development (IAD) framework

The IAD framework by Ostrom (Citation1990, Citation2005, Citation2007) is suitable for understanding not only how institutions work but also how they change and evolve. Institutions matter as determinants of the context in which human interactions take place (Florensa, Citation2004). Rules-in-use are ‘institutions in their purest form’ (Van den Hurk et al., Citation2014, p. 418). Rules-in-use (or working rules) are defined by Ostrom (Citation2007, p. 36) as ‘the set of rules to which participants would refer if asked to explain and justify their actions to fellow participants’. To bring some order to the massive number of rules, Ostrom (Citation2014) categorizes the rules into seven types, based on the elements of the action situation to which they refer. She considers human interaction as made by participants entering action arenas (boundary rules), holding positions (position rules), choosing among actions at a particular stage of the decision-making process (aggregation rules), based on their control (authority rules), the information they have (information rules), the likely outcomes (scope rules), and the assessment of benefits and costs deriving from these outcomes (payoff rules).

Rules-in-use is only one of the three external variables potentially affecting the action arena, in which actions are implemented by actors involved in an action situation, resulting in patterns of interactions and outcomes. To build a more general theoretical understanding of how institutions work, persist and change over time, Ostrom considers two more exogenous variables potentially affecting the action arena (): physical/material conditions and attributes of the community. Physical/material conditions determine policy choices and the extent to which actions are physically likely to occur or outcomes are produced (e.g., high urban density may hamper the implementation of nature-based solutions). Attributes of the community include preferences of participants in achieving specific outcomes, their knowledge, information and beliefs, and the consideration of other participants involved (Clement, Citation2010; Ostrom, Citation2007), all of which are likely to affect behaviour in human-interaction situations (Ostrom, Citation2014). By looking at the variable of outcomes, we looked at the decisions taken by national decision-makers in terms of courses of action to be pursued in flood risk management (e.g., a national strategy of flood control infrastructure for flood probability reduction).

Figure 1. Politicized institutional analysis and development framework.

Clement (Citation2008, Citation2010) explains that one of the limitations of the IAD framework is the lack of consideration of the role of power distribution and the extent to which this affects the patterns of interaction and final decisions. By drawing on Ostrom’s IAD, Clement (Citation2008, Citation2010) adds two more exogenous variables to the framework, namely, the politico-economic context and discourses (). By looking at the politico-economic context, researchers will be able to understand how power is distributed among the actors who take decisions and the extent to which political and economic interests drive actors’ decisions within a set of rules-in-use. By considering the variable of discourses, the role of values, beliefs and norms in shaping the preferences of actors involved in decision-making processes is emphasized (Hajer, Citation1995). As a member of a community of actors may support a specific discourse, the variables of discourses and attributes of the community are related and will be jointly discussed.

For the analysis of discourses, we looked at the indicators for the presence of specific discourses of resilience in the discussions on flood risk policies (Vitale et al., Citation2020) and the extent to which these have influenced policy outcomes. Notably, the discourses of engineering, ecological and socio-ecological resilience prescribe diverse substantive and governance strategies to enhance urban flood resilience (De Bruijn et al., Citation2017; CitationDavoudi et al., Citation2012, 2013; Holling, Citation1996). Decision-makers may consider it central to act on flood probability reduction via hard control infrastructure to reduce flood hazards (engineering resilience). Decision-makers may also acknowledge the importance of flood vulnerability and exposure reduction (ecological and socio-ecological resilience). Vulnerability reduction may be achieved by improving early warning and emergency measures or adjusting individual houses and infrastructure. Exposure reduction may be pursued by preventing urbanization in floodplains or through de-urbanization programmes (Meijerink & Dicke, Citation2008; Oosterberg et al., Citation2005). Engineering and ecological resilience share the idea of stability, be it a pre-existing state to which the system bounces back (engineering) or a new status to which it strives for (ecological) (Davoudi et al., Citation2012). The socio-ecological resilience discourse highlights the role of people as ‘agents of the ecosystem’ (Folke, Citation2006) and their ability to cope with external disturbances (e.g., improving social learning for flood risk mitigation) (Adger, Citation2000).

Research methods

In our data collection and data analysis, we followed a three-step procedure. First, each variable of our politicized IAD framework was operationalized into a coding scheme (see the supplemental data online). Second, we reviewed the academic literature on the evolution of Italian flood risk management policies to learn more about the variables of our framework. Third, we manually collected and coded the most important policy documents on Italian flood risk policies, such as policy reports, policy assessments, laws and regulations ().

Table 1. Overview of the consulted policy documents.

The selected time frame (1952–2020) is sufficiently long to be able to trace continuity and change in flood risk policies. We have split this time frame into three distinct phases, each marked by significant policy changes. The first phase begins in 1952, when, following the 1951 flood in Polesine, a more comprehensive plan to deal with flood risk was approved. This phase ends in 1989, with the first law on soil protection (Law 183/1989) (President of the Italian Republic, Citation1989). Notably, for the first time, Law 183/1989 encompassed a catchment-based approach and established the river basin authorities. The second phase (1990–2006) was characterized by a gradual devolution of power in flood risk management and a slow process of Europeanization. This phase ends in 2006, when the legislative decree 152/2006 (better known as the Environmental Code) (President of the Italian Republic, Citation2006) abrogated the law on soil protection 183/1989 and transposed the water framework directive (WFD) in the national legislation. The transposition of the WFD into the national legislation induced some innovations. As an example, the former river basins were replaced by the hydrographical districts with consequences for river basin management in terms of flood risk management strategies and actors involved. The third phase (2007–20) is marked by the latest national programmes of measures to be implemented to mitigate flood risk. These programmes strongly relied on flood protection measures, thus hampering the paradigm shift from a standards-based towards a risk-based approach, which was partly initiated a few years earlier.

Continuity and change in Italian flood risk policies between 1952 and 2020

In this section, we present the findings of our institutional analysis of flood risk policies in Italy between 1952 and 2020. An overview of these findings is provided in .

Table 2. Overview of the analysis of flood risk policies in Italy between 1952 and 2020.

1952–89: A standards-based approach

Physical/material conditions

Italy is largely covered by mountains and hills. The hydrological regime of the Alpine rivers is connected to the glaciers and the presence of snow and is characterized by floods during the summer and low discharge during winter. Notably, the regime of the pre-Alpine and Apennine rivers is rain dependent, with floods mostly occurring during spring or autumn and low flow during other seasons (Gallozzi et al., Citation2020; Massarutto et al., Citation2003). However, hydrogeological features and the intensity of weather events are not the only causes of flood risk exacerbation. The economic and building boom that followed the end of the Second World War in 1945 triggered largely unplanned and uncontrolled urbanization in floodplains (Palmieri, Citation2011). Several rivers were tamed, channelled or straightened first for agricultural purposes (Moccia, Citation2020) and, later, to create room for urban development. These rivers soon became the receptacles of agricultural, industrial and urban wastewater, further exacerbating the negative consequences of floods (Rainaldi, Citation2009).

Politico-economic context

The Fascist regime (1922–43) strengthened political and financial centralism, which was only partly undermined by the fall of Fascism in 1943. The Republican Constitution, which came into effect in 1948, made the first attempt towards power decentralization by establishing the regions. Despite the constitutional provisions, the regions started to function only in the 1970s when the election of regional councils became possible. The origin of this delay was partly political, driven by the fear of possible frictions between regional and central forces. Ruling classes feared that regions would be governed by representatives of different political parties than the ruling ones during the Cold War (1947–91). The regions continued to have rather limited power, fiscal autonomy and possibilities for participation in constitutional choices in the years to come (Baldini & Baldi, Citation2014).

Meanwhile, Italy economically converged towards the most advanced countries driven by the economic boom that followed the end of the Second World War (Clementi et al., Citation2015). The economic recession in 1976 partly slowed economic growth globally (Lubitz, Citation1978). The public sector was affected by the recession significantly, resulting in lower investments in public infrastructure. Financial resources were mostly invested in landslide risk management to protect the mountains from deforestation and soil erosion determined by the abandonment of agricultural activities (Farcomeni, Citation2019). Additionally, funding from the state budget for implementing flood risk protection measures was rather limited and discontinuous. National funding was mostly geared towards post-disaster management via the service of civil protection, established in the current structure of national service in 1992 (Law 225/1992) (De Bernardinis & Casagli, Citation2015). Regional, provincial and municipal civil protection units were established, each under the direct control of the state department of civil protection.

Attributes of the community and discourses

Following the disastrous floods in Polesine (1951; 100 casualties), Amalfi (1954; 318 casualties) and Florence (1966; 35 casualties), the government instituted the De Marchi Committee in 1967. The De Marchi Committee was entrusted with in-depth studies on the causes of national landslide and flood risks and the design of new principles for hydraulic risk management and soil protection. It issued a study report in 1970 that included a plan to combat national landslide and flood risks (De Marchi Committee, Citation1970). For the first time, the epistemic community of hydrologists represented in this committee advocated a catchment-based approach and combined attention to water quality and quantity issues (Farcomeni, Citation2019; Gallozzi et al., Citation2020; Mysiak et al., Citation2013; Rainaldi, Citation2009; Scolobig et al., Citation2014). The study focused primarily on protecting agriculture from floods (De Bernardinis & Casagli, Citation2015).

The findings of the De Marchi Committee triggered an extensive debate that lasted for almost 20 years and was interrupted by floods, emergency regulations and legislature turnover (De Bernardinis & Casagli, Citation2015; Rainaldi, Citation2010). Finally, the first law on soil defence was adopted in 1989 (President of the Italian Republic, Citation1989). By drawing on the concept of soil protection introduced by the De Marchi Committee, Law 183/1989 combined two traditionally separated fields: hydraulic protection and soil protection (Gallozzi et al., Citation2020; Scolobig et al., Citation2014). Historically, hydraulic protection was the task of the Minister of Public Works, and consisted of hydraulic measures to reduce flood probability; soil protection was the responsibility of the Ministry of Agriculture and concerned the protection of agriculture and forestry (Gallozzi et al., Citation2020).

Law 183/1989 represented a turning point and marked the beginning of modern flood risk management, an era in which new flood risk management discourses challenged beliefs and consolidated positions. A shift towards an integrated approach to flood risk management was made by considering the river basin and combining former sectoral policies, such as water resource management, soil conservation, water quality and water quantity (Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale [ISPRA], Citation2020; Massarutto et al., Citation2003). Through this law, for the first time the river basin plan incorporated actions to be implemented according to flood risk classes (Lombardi, Citation2016), becoming legally binding for spatial planners, and promoting spatial transformations depending on flood risk.Footnote1 Finally, local councils were asked to update existing land use plans according to the river basin plan dispositions (Lombardi, Citation2016). The importance given to spatial planning measures (in combination with catchment-based measures) encouraged a shift from engineering resilience (a dominant focus on hazard reduction measures) to ecological and socio-ecological resilience discourses and increased attention to vulnerability (e.g., building adjustments or waterproof architecture) and exposure reduction measures (e.g., de-urbanization).

Rules-in-use

The Ministry of Public Works led the flood risk management sector for a long time, with structural measures financed and implemented according to the principle of control over nature (Farcomeni, Citation2019; Goria & Lugaresi, Citation2004). The first governmental attempt towards a more integrated approach was made in the aftermath of the 1951 Polesine flood by adopting a general plan that required coordinated attention to agriculture, hydroelectricity and navigation to limit soil erosion and watercourse overflow (Law 184/1952 and follow-up Law 11/1962) (Gallozzi et al., Citation2020); the plan was a task of the Ministry of Public Works, in collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (President of the Italian Republic, Citation1952, Citation1962).

The action arena remained relatively closed until the 1970s, when the set of actors involved in flood risk management was extended (Goria & Lugaresi, Citation2004). The most important developments are: (1) competencies on flood prevention and first aid were transferred from the Ministry of Public Works to the Ministry of Domestic Affairs (Law 996/1970); (2) the regions were assigned the task of designing and implementing protection measures and post-disaster management (Decree 616/1977) (President of the Italian Republic, Citation1977); and (3) the Ministry of Environment was established (Law 349/1986) (President of the Italian Republic, Citation1986). The Ministry of Public Works preserved most of the tasks concerning soil protection (Farcomeni, Citation2019; Gallozzi et al., Citation2020; Goria & Lugaresi, Citation2004; Scolobig et al., Citation2014).

The first law on soil protection was approved in 1989. Law 183/1989 (President of the Italian Republic, Citation1989) introduced the catchment-based approach, established the river basin authorities, and required the adoption of river basin plans (De Bernardinis & Casagli, Citation2015; Gallozzi et al., Citation2020; Goria & Lugaresi, Citation2004; Mysiak et al., Citation2013; Rainaldi, Citation2009). The Presidency of the Council of the Ministers was entitled to coordinate, control and approve the river basin plans with the dominant role of the Ministry of Public Works and the ad hoc established National Committee for Soil Defence. The measures to be implemented were collected in triennial programmes drafted by the river basin authorities and enclosed in the river basin plans, financed by the state, and implemented by the regions and the Ministry of Public Works. Notably, the Ministry of Environment, set up three years earlier, only had the authority to oversee and regulate water pollution and wastewater disposal (Gallozzi et al., Citation2020).

Outcomes

For decades, flood risk mitigation was pursued via structural measures for flood probability reduction. The De Marchi Committee emphasized the importance of adopting a catchment-based approach for flood risk mitigation and encouraged coordinated attention to flood risk management, water quality and emergency management. Nevertheless, flood risk was still tackled via hazard reduction measures (e.g., embankments and spillways), providing a false sense of security which further encouraged floodplain occupancy. Law 183/1989 was approved only 20 years after the De Marchi Committee had issued its advice. By introducing the catchment-based approach, the law challenged the allocation of existing tasks and responsibilities that were formerly based on administrative boundaries. In addition, the newly introduced river basin plan made future spatial choices depending on flood risk classes – for instance, by limiting urbanization in high flood risk zones. Because of affecting intended spatial planning choices, the river basin regulations did not always gain the support of local administrators and citizens. As an example, according to the new regulations, building permissions could no longer be granted for new constructions in hazard flood areas, thus limiting landholders’ development perspectives.

1990–2006: Attempts to transition towards a risk-based approach

Physical/material conditions

In a recent report on the evolution of land cover and land use in Italy, the Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale (ISPRA)Footnote2 reported that 8000 ha were urbanized between 1990 and 2000 and an additional 9000 ha between 2000 and 2006 (ISPRA, Citation2018). Floodplain occupancy continued further aggravated by unauthorized planning practices. Introduced in 1985 (and renewed in 1994 and 2003), the condono edilizio, or building amnesty, secured legitimization to buildings built without planning permit (Zanfi, Citation2013). Both formal (e.g., building amnesties) and informal institutions (e.g., criminal organizations) prompted unauthorized floodplain occupancy (Chiodelli, Citation2019). Local authorities have often colluded with criminal organizations (De Leo, Citation2017), traditionally interested in building construction works. Poor monitoring and scarce enforcement may explain the gap between formal and informal institutions and the extent to which policy outcomes have deviated from the policy as intended.

Politico-economic context

The institutional decentralization that started in the 1970s was prompted in the 1990s following the Bassanini reforms (Laws 59/1997, 127/1997 and 191/1998), a set of laws specifically targeting the distribution of tasks and competencies between central, regional and local governments (Bassanini, Citation2011). Until the Bassanini reforms, a long-lasting dualism between central and regional forces characterized the management of water resources, with the state preserving most competencies and tasks over soil defence; this has been later acknowledged as one of the reasons behind the lack of a coherent water policy (Massarutto, Citation1999). This devolution of power to the regions was further driven by the European Community and the availability of a system of aid for the regions, the European Structural Funds (1975), to be invested by regional governments. However, ‘the state still ruled over local authorities and regions struggled to carve out their role in territorial governance’ (Baldini & Baldi, Citation2014, p. 102). Although the introduction of the European Monetary System and the Eurozone (2002) partly affected the national economic autonomy (Garofoli, Citation2016), public investments continued (Sorrentino, Citation2019).

Attributes of the community and discourses

Following major floods in the Sarno (1998; 160 casualties) and Soverato (2000; 13 casualties) river basins, new policies were promptly adopted to extend the set of actors and broaden the scope of flood risk mitigation measures. In addition, the WFD triggered new changes in flood risk management policies. As an example, participation was considered important for democratic deliberation, information sharing and social learning to enhance disaster preparedness and risk perception (Miceli et al., Citation2008). Between 1990 and 2006, innovations in flood risk management policies encouraged a shift from a standards-based towards a risk-based approach; this attempt was hampered by the existing top-down and technocratic approach to flood risk management. For example, participation was primarily seen as a means of enhancing effectiveness rather than a transformation of policy styles (Massarutto et al., Citation2003). In response to this top-down planning approach, in the early 2000s, river contracts were initiated as bottom-up voluntary planning practices by local actors. Lombardia and Piemonte were the first two Italian regions promoting river contracts in Italy (Bastiani, Citation2011; Regione Lombardia et al., Citation2012). In the river contract, co-planning and collaboration among private and public actors involved in water management and urban planning are advocated to achieve inclusive decision-making processes and take shared decisions on river basin management (Bianchini & Stazi, Citation2017). The result of this process of deliberation and negotiation is an action programme of measures to be implemented, supplemented with an implementation schedule, financial allocation scheme, and overview of tasks and responsibilities. However, as pointed out by Massarutto et al. (Citation2003), despite the interesting bottom-up attempts, these voluntary agreements were incidental and did not change the dominant top-down style of decision-making.

Rules-in-use

The adoption of the river basin plan required by Law 183/1989 proved to be more difficult than expected. Adopted in the aftermath of the Sarno flooding, the Sarno decree (Decree-Law 180/1998, converted in Law 267/1998) (President of the Italian Republic, Citation1998) set stricter deadlines for delivering landslide and flood risk plans, speeding up the process of mapping hazard and flood risk areas; additionally, the decree required the definition of land use based on flood risk classes and established new regulations for adjusting or delocalizing buildings and infrastructure in high-risk areas (Gallozzi et al., Citation2020; Mysiak et al., Citation2013). The adjustment and delocalization of buildings and infrastructure, which was the responsibility of the regions, remained optional for householders and was barely implemented in practice (De Bernardinis & Casagli, Citation2015). The national government was entitled to take action in case of non-compliance (Gallozzi et al., Citation2020; Mysiak et al., Citation2013; Testella, Citation2011). In the aftermath of the Soverato flood event, the Soverato decree (Decree-Law 279/2000, converted in Law 365/2000) introduced the programmatic conference to convene all relevant actors (e.g., provinces, municipalities, river basin authority) for joint decision-making (De Bernardinis & Casagli, Citation2015; Gallozzi et al., Citation2020; Testella, Citation2011) and to enhance the coherence between spatial planning choices and river basin management. River basin plans became soon legally binding for spatial planning (De Bernardinis & Casagli, Citation2015).

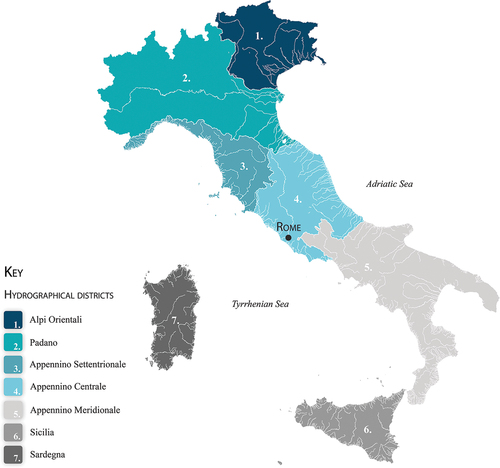

In 2002, the Italian Ministry of Environment was formally entrusted with soil protection (Law 179/2002) (President of the Italian Republic, Citation2000), thus completing the transfer of competencies started in 1989. A few years later, the WFD triggered new institutional changes. Transposed in the national legislation via legislative decree 152/2006 (President of the Italian Republic, Citation2006), the WFD formally abrogated the law on soil protection 183/1989. The institutional changes induced by the WFD can be summarized as follows: (1) the country was divided into eight hydrographical districts (later reduced to seven), which replaced the former river basin authorities, and were entrusted with the hydrographical district plans (); (2) the hydrographical districts were under the direct supervision of the Ministry of Environment (Gallozzi et al., Citation2020); (3) the hydrographical district authority was recognized as a planning agency, but without implementation rights (Rainaldi, Citation2009); and (4) the hydrographical district plan – up to the hydrographical district authority – was first adopted by the steering committee (consisting of representatives of the regions and ministries) of the hydrographical district authority by majority rule and later approved by the prime minister.

Outcomes

The disastrous floods in Sarno and Soverato paved the way for discussions about the use of non-structural alternatives in flood risk mitigation. The limitations of spatial development choices based on flood risk classes, the consideration of spatial planning for flood risk mitigation, and the proposal of adjusting and delocalizing buildings in free-flood risk areas represented an important step forward in overcoming the passive concept of soil protection (De Bernardinis & Casagli, Citation2015). The Sarno decree switched the focus from protecting agriculture (particularly emphasized in the De Marchi Committee’s work and perfectly in line with the economic context of the late 1960s) to protect local communities and properties. This switch of focus was followed by the gradual empowerment of the civil protection department (De Bernardinis & Casagli, Citation2015), which strengthened the discourses of ecological and socio-ecological resilience, giving increasing importance to measures aimed at reducing the vulnerability of people and goods, while simultaneously working on flood control infrastructure (focus on hazard reduction).

One of the consequences of the fact that river basin planning became legally binding for spatial planning choices was that the definition of high-risk areas became the object of bargaining between water managers and local administrators. In many cases, the defined high-risk areas deliberately excluded certain urban areas to preserve urban value and secure future spatial development. As argued by Rainaldi (Citation2009), when considering the number of actors potentially interested in river basin planning and the extent to which river basin planning regulations might affect spatial planning choices, it is clear why this is going to meet some resistance. For these reasons, despite the attempts to increase the diversification of actors and measures in flood risk mitigation, a proper paradigm shift towards a risk-based approach was hindered by advocates of a more traditional approach. This traditional approach was further secured by recentralization attempts made by the state in those years to preserve a leading role in funding allocation and final decisions.

2007–20: A failed transition

Physical/material conditions

In a recent report on the evolution of land cover and land use in Italy, ISPRA reported that 7000 ha were urbanized between 2006 and 2012 and an additional 4000 ha were urbanized between 2012 and 2017 (ISPRA, Citation2018). In 2018, according to ISPRA, approximately 2,062,475 inhabitants (3.5%) lived in a high flood hazard area (P3) (flooding return time of 20–50 years), 6,183,364 (10.4%) people lived in a medium flood hazard area (P2) (flooding return time of 100–200 years), and 9,341,533 (15.7%) in a low flood hazard area (P1) (very low probability); the buildings in the medium flood hazard class (flooding return time of 100–200 years) were 1,351,578 (approximately 9.3% of the total buildings) (Trigila et al., Citation2018).

Politico-economic context

Between 2007 and 2020, together with the empowerment of regional authorities that are entrusted with increasing responsibilities, the state strengthened its power over final choices and funding allocation. In addition, the civil protection department became a powerful player, with tasks on prevention, forecasting, monitoring and disaster response coordination. Under the direct control of the prime minister, the civil protection department, established by Law 225/1992 (President of the Italian Republic, Citation1992), was in charge of disaster management and entitled to replace local governments in the management of emergencies. Whereas the state intervention helped local governments to cope with extraordinary emergencies in some cases, more often it was interpreted as an attempt to exercise control over local authorities (Farcomeni, Citation2019). By declaring the state of emergency, ad-hoc responses were provided without substantially discuss the management of actual and future risks (Mysiak et al., Citation2013; Testella, Citation2011).

In 2008, Italy was hit hard by an economic crisis, mainly caused by financial speculations in real estate (Osti, Citation2017). As a consequence, investments in public infrastructure were reduced dramatically (Associazione Nazionale Costruttori Edili [ANCE], Citation2012; Fabrizi et al., Citation2015). Low-rate bank loans, tax breaks and easy building concessions in those years were followed by a real estate and housing bubble which caused the collapse of several construction companies (Osti, Citation2017). Investments in flood risk management, however, continued thanks to the support of ad hoc EU funding streams.

Attributes of the community and discourses

Between 2007 and 2020, the importance of focusing on exposure and vulnerability reduction measures for flood risk management was emphasized. As an example, this was included in the national strategy for climate adaptation, which advocated for better coordination between structural and non-structural measures for flood risk management (Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare [MATTM], Citation2015). Approved in 2015 (MATTM, Citation2015), the climate change adaptation strategy pointed at the factors exacerbating flood risk in Italy and offered a set of measures and strategies to be implemented for reducing flood risk. As non-structural measures, the strategy emphasized the importance of spatial planning decisions, improved emergency responses and the importance of bottom-up initiatives (such as the river contracts). However, while emergency management measures were further developed (under the direct control of the central government), the role of spatial planning for flood risk mitigation remained marginal. A national plan for climate change adaptation, further specifying the measures to be implemented to achieve the goals of the climate change adaptation strategy was also elaborated (MATTM, Citation2018). The plan emphasized the importance of nature-based solutions, in line with the European adaptation strategy. However, besides the fact that this plan has not yet been adopted due to delays, it did not allocate the necessary financial resources for its implementation. Meanwhile, the latest national programmes of measures for flood risk mitigation, such as Italia Sicura (2014) and Proteggi Italia (2019), continued to be focused on hazard reduction via flood control infrastructure programmes.

Rules-in-use

Following major floods, the government financed (via the Finance Act 2010) new programmes of measures for flood risk mitigation to be implemented in high-risk areas. The measures were supposed to be implemented via programme agreements, arranged between the Ministry of Environment and the regions once they agreed upon the expenditure of state and regional financial resources. The Ministry of Environment was entitled to select measures, based on advice from the national civil protection department and hydrographical district authorities (Gallozzi et al., Citation2020). However, the formula of programme agreements and supervision from regional presidents did not help to overcome implementation issues. For this reason, in 2014, the Presidency of the Council of the Ministers established Italia Sicura, a technical structure under the direct control of the prime minister. Italia Sicura was established to implement, coordinate, monitor and control interventions for mitigating national landslide and flood risks. In 2015, Italia Sicura adopted a national programme of measures to be implemented over five years (Galletti et al., Citation2017). The distribution of tasks and competencies was done as follows (also following the Sblocca Italia Decree 133/14, converted in Law 164/2014): regions applied for financing to the Ministry of Environment; the Ministry of Environment transferred financial resources to the regions (which could participate using their financial resources) via programme agreements; the presidents of the region were responsible for project implementation and monitoring; the Ministry of Environment was entrusted with supervision and control over project implementation together with ISPRA. The Ministry of Environment and ISPRA revoked financing in case of non-compliance (Gallozzi et al., Citation2020). In addition, via the Sblocca Italia decree (133/2014), financial resources were specifically targeted to a set of most urgent measures to be implemented in metropolitan cities. The role of the regions was strengthened as regional presidents became responsible for securing the implementation of projects and measures (Decree-Law 133/14) (Gallozzi et al., Citation2020). In 2018, the new government closed Italia Sicura, and transferred its tasks and competencies to the Ministry of Environment. In 2019, Proteggi Italia, a new national plan of measures to mitigate landslide and flood risks, was adopted (President of the Council of the Ministers, Citation2019). Emergency, prevention and maintenance measures were allocated as follows: emergency measures to the civil protection department; prevention measures to the Ministry of Environment; maintenance measures to the Ministry of the Forestry, Ministry of Infrastructure and the Ministry of Domestic Affair (Gallozzi et al., Citation2020). Meanwhile, in 2010, the Floods Directive (FD) was transposed in the national legislation via legislative decree 49/2010 (President of the Italian Republic, Citation2010). Italy was divided into (47) units of management supervised by (54) competent authorities; the legislative decree 49/2010 assigned to the hydrographical district authorities the tasks of fulfilling the FD requirements, with the regions responsible for emergency management (together with the national department of civil protection) (Gallozzi et al., Citation2020).

Outcomes

The formula of programme agreements made the implementation of measures for flood risk mitigation dependent on the concertation between the regions and the state. This devolution of power and competencies to the regions, however, was accompanied by recentralization attempts, as the state retained the ultimate decision-making power over funding allocation. The latest national programme of measures for flood risk management, Italia Sicura (2014) and Proteggi Italia (2019), were characterized by a sectoral approach to flood risk management, with a strong focus on structural measures for flood protection. Defined in agreement with the hydrographical district authorities, these national programmes barely considered measures to implement other than flood control infrastructure; spatial solutions for flood risk mitigation have hardly been implemented in practice. The national climate adaptation strategy is partly disregarded. The main focus on reinforcing flood protection infrastructure was motivated by physical/material conditions, such as a lack of space to create nature-based solutions (e.g., room for the river), and the need for a quick response to increasing risks.

Discussion and conclusions

This study enhances our understanding of continuity and change in the national flood risk management policies in Italy between 1952 and 2020. In this section, we first introduce the overall conclusions and then engage in a broader discussion.

The first phase (1952–89) was dominated by the hydraulic paradigm and undisputed confidence in technology (Rainaldi, Citation2009). Flood risk mitigation was achieved via flood protection measures for hazard reduction, with a strong emphasis on engineering resilience and a standards-based approach. The second phase (1990–2006) was characterized by a gradual devolution of power in flood risk management, which broadened the set of actors and measures to cope with flood risk. As an example, spatial planning was recognized as a crucial factor in flood risk management. Values of ecological and socio-ecological resilience were increasingly incorporated, prompting a gradual shift towards a risk-based approach. During the last phase (2007–20), the central government regained power over final choices and funding allocation. Despite the formerly advised combination of structural and non-structural measures in flood risk mitigation, flood control infrastructure remained a priority. Therefore, instead of further strengthening the risk-based approach, flood risk management policies continued following an engineering-oriented approach. We can thus conclude that Italian flood risk policies are characterized by continuity rather than by change, and that the transition towards a risk-based approach has failed.

The empirical analysis presented in this study, which is based on the politicized IAD framework, provides interesting insights into some of the main factors that explain this continuity in flood risk management. By unpacking the five external variables potentially affecting action situations and outcomes, we were able to unravel the material, political, discursive and institutional factors hindering the transition towards a risk-based approach. To begin with, looking at the (1) physical/material conditions, the most important observation is that floodplain occupancy has continued over the past decades. This has reduced the natural water storage capacity of the river basins and increased the probability and potential impacts of floods. When looking at the changes in the (2) politico-economic context, what stands out the most is the power play between the national government and the regions. The national government managed to strengthen the central power over time, especially over funding allocation and final decisions. This can be better understood by looking at the (3) attributes of the community of actors involved and (4) discourses of resilience in flood risk policies. Our empirical findings show that Italian flood risk management remains a technical domain primarily dominated by experts in building flood control infrastructure. These experts hardly consider alternative courses of action, and spatial policies for flood risk reduction are poorly developed. Because of the centralized approach in flood risk management, the adoption of ecological and socio-ecological resilience measures is hindered, as these also depend ‘on the availability of tailor-made governance arrangements’ (Gersonius et al., Citation2016, p. 7). Flood risk management is not only about structural and non-structural measures, but it is also a matter of ‘societal transformations and successful governance approaches’ (Driessen et al., Citation2016, p. 1). The set of institutions or rules-in-use guiding the interactions within the national action arena are very much related to the developments described above. Due to the changing attributes of the community of actors involved in flood risk policies and the increasing influence of the EU, we see an increase in the variety and number of stakeholders involved in flood risk management, and an increase in the scope, from a focus on flood protection only towards a risk-based approach. However, this has been not sufficient for a successful transition towards a risk-based approach.

The institutional analysis presented in this study provides insights into the factors that may explain continuity in flood risk management policies in Italy. As Wolsink (Citation2006, p. 474) in his study on flood risk management in the Netherlands argues, a policy shift ‘must be made effective in a domain that is replete with actors who operate according to old institutional arrangements and accustomed practices’. Italian flood risk management is characterized by continuity rather than by change, and this may be partly explained by mechanisms of path dependence; institutions tend to reproduce and self-reinforce, thus becoming persistent (Peters et al., Citation2005; Pierson, Citation2000). In Italy, attempts to change from path-dependent trajectories were made only after major floods, which acted as ‘windows of opportunity’ (Kingdon, Citation1984). However, as Mysiak et al. (Citation2013, p. 2886) argue, the fact that flood risk management in Italy has often evolved as a response to large natural calamities, has resulted in a ‘normative framework punctuated with ad hoc and insufficiently coordinated pieces of legislation’. The occurrence of shock events has triggered targeted financial resources and ad hoc policy responses driven by a lack of attention to the core of policies, guiding principles or preferences, without substantially questioning the management of actual and future flood risks (Mysiak et al., Citation2013; Testella, Citation2011). The emphasis on emergency responses has precluded the production of long-term strategic visions and investment strategies. The establishment of the civil protection department, progressively strengthened in its role and responsibilities, and the significant financial resources targeted to ex-post disaster management have normalized post-disaster responses and undermined proactive planning attempts (Rusconi, Citation2010). This is why, ‘shock events do not necessarily account for radical policy change’ (Meijerink, Citation2005, p. 1074). The concept of path dependence, in which earlier steps in a particular direction induce further movements in the same direction, is well captured by the idea of ‘increasing returns’ put forth by Pierson (Citation2000). As Pierson (Citation2000, p. 252) argues, ‘in an increasing returns process, the probability of further steps along the same path increases with each move down the path’. This means that once a path is chosen, it may be too costly to leave this path (Van Buuren et al., Citation2016).

Path dependence has been partly favoured by physical/material conditions in the country, which have hampered the implementation of spatial strategies for flood risk mitigation, for instance, due to the ongoing floodplain occupancy. Because of the dominance of the engineering resilience discourse, the main response to shock events was primarily to build new flood protection infrastructure, which encouraged further urbanization, thus increasing the potential damages of future flood events. In the literature, this phenomenon is referred to as the ‘control paradox’ (Remmelzwaal & Vroon, Citation2000; Wiering & Immink, Citation2006), an important mechanism explaining path dependence. In most recent years, forecast management and alert systems have been considerably improved. However, exceptional weather events may be difficult to predict sufficiently in advance to alert citizens; this is why, as Mysiak et al. (Citation2013, p. 2886) point out, it is equally important to act on the built environment by reducing the vulnerability and exposure to ‘extreme precipitation and flash flood events that are hard to predict with sufficient temporal and spatial resolution’.

Yet, spatial strategies for flood risk mitigation have not only been hampered by bio-physical features. The power play between the central state and the regions has played a role in preserving continuity in Italian flood risk management. We cannot understand this power play between the central and regional forces without considering the evolution of the organization of the Italian state. Over the past decades, several countries have supported the decentralization of governmental functions as a means of ‘promoting both democratic and developmental objectives’ (Hutchcroft, Citation2001, p. 23). Grounded on ‘unitary-centralized’ lines, the Italian nation-state attempted a shift towards a ‘unitary decentralization’ following the Second World War (Leonardi et al., Citation1981, p. 95). In a unitary decentralized state, compared with federal countries, regions are created more often as a result of top-down planning, rather than to preserve ‘territorial pluralism’ (Baldini & Baldi, Citation2014, p. 90). This is the reason why despite the devolution of some power to the regions (concerning flood risk policies), the state managed to maintain or regain power over them. Besides, the state has traditionally preserved a key role in matters concerning natural resources and natural hazard management, as also proved by the reform of the Constitution (Title V, Art. 117) for what concerns the allocation of the tasks between the regions and the state; the state has once again preserved a leading role in defining strategic objectives and guidelines for risks management.

As demonstrated by our analysis of discourses, adopting new values and measures and broadening the set of actors involved in flood risk management has not been a smooth process, and, in any case, is not sufficient for a proper paradigm shift in flood risk management. A widely accepted engineering approach to flood risk management in the community of actors entitled to deal with flood risk mitigation remains dominant; further supported by established knowledge, networks and information. The dominant set of actors feels threatened by opening up the decision-making process and welcoming forces, values, ideas potentially undermining their identity (Pahl-Wostl et al., Citation2013). As Pahl-Wostl et al. (Citation2013, p. 13) contend, the integration of participation into a technocratic management approach ‘seems to be more threatening to the identity of an expert culture’. The variety of rules and laws issued in Italy over the past decades has too often resulted in an unclear allocation of tasks and competencies among actors involved, overlaps and lacking coordination. This lack of coordination, both across layers of government (vertical) and between organizations involved in flood risk management and spatial planning (horizontal), has partly undermined attempts towards changes in flood risk policies. As an example, the prescriptions of the river basin district authorities concerning planning choices in flood risk areas have often been disregarded in local planning practice, which has allowed new urban development in floodplains. In addition, the unclear division and allocation of tasks and competencies between the actors involved has left space for unauthorized constructions in floodplains. Informal planning practices in flood risk zones demonstrate that rules-in-use may deviate from formal rules, which hampers the transition towards a risk-based approach in flood risk management.

In Italy, the strong bias towards flood probability reduction measures has been only recently questioned by EU policies, collaborative bottom-up initiatives (such as the river contracts) and learning within the epistemic communities of actors involved in Italian flood risk management. Acknowledging the crucial role of structural measures for flood probability reduction, uncertain climate change scenarios and urban growth ask for diversification of strategies and the equal consideration of flood vulnerability and exposure reduction measures to cope with actual and future risks. This diversification is, however, hardly achieved in practice. As an example, the active role of local governments in meeting flood risk management goals via spatial planning choices which are consistent with flood risk conditions is still lacking. Although land use can significantly influence ‘the future development of the damage potential in flood-prone areas’ (Petrow et al., Citation2006, p. 721), local officials and residents tend to underestimate or even deny local risks. This may be partly explained by their belief that flood risks need to be managed centrally.

The politicized IAD framework allowed us to conduct more than an institutional analysis. The framework does not claim the superiority of institutions by taking into account physical/material conditions, politico-economic context, discourses, and attributes of the community, along with rules-in-use (institutions), as factors that may explain patterns of interaction and outcomes. The ‘decomposability of the IAD framework’ allows the study of complex collective action situations, ‘by breaking it down into its several components’ (Clement, Citation2008, p. 33). This has been helpful in finding mechanisms of path dependence in Italian flood risk management, such as the control paradox, the Italian state structure, which hampers decentralization efforts, the dominance of the engineering resilience discourse and the belief that flood risk management is primarily a state responsibility. Despite the observed path dependence, the increasing frequency and impact of flood events and the expected long-term effects of climate change are strong arguments for prompting a better integration between flood probability reduction and exposure and vulnerability reduction measures. Former attempts towards a paradigm shift may be seeds of change, which eventually contribute to change in Italian flood risk policies.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (166.1 KB)Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2021.1985972.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. The flood and landslide management plans are meant to identify areas prone to risk based on flood risk classes, arranged as follows: R4 (very high-risk class, loss of life), R3 (high-risk class, possible harm to humans), R2 (medium risk class, no direct threat for people) and R1 (low risk class, no threat for people).

2. The Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale (ISPRA) was established by Law 133/2008. It is a public research institute under the direct control of the Ministry of Environment.

References

- Adger, W. N. (2000). Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Progress in Human Geography, 24(3), 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913200701540465

- Alexander, M., Priest, S., & Mees, H. (2016). A framework for evaluating flood risk governance. Environmental Science & Policy, 64, 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.06.004

- Associazione Nazionale Costruttori Edili [ANCE]. (2012). The crisis of the construction sector in Italy during the early 1990s and the current crisis Extract from the economic observatory on the construction industry [La crisi delle costruzioni dei primi anni novanta e la crisi attuale. Estratto dall’Osservatorio Congiunturale sull’Industria delle Costruzioni].

- Baldini, G., & Baldi, B. (2014). Decentralization in Italy and the troubles of federalization. Regional & Federal Studies, 24(1), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2013.827116

- Bassanini, F. (2011). Federalizing a regionalised state. Constitutional change in Italy. In A. Benz & F. Knüpling (Eds.), Changing federal constitutions: Lessons from international comparison (pp. 1–20). Barbara Budrich Publishers.

- Bastiani, M. (2011). River contracts. Strategic and participatory planning for river basins management. Approaches – Experiences – Case studies [Contratti di fiume. Pianificazione strategica e partecipata dei bacini idrografici. Approcci–Esperienze–Casi studio]. Dario Flaccovio Editore.

- Bianchini, A., & Stazi, F. (2017). River contracts in Italy (and across the boarders). 10th national meeting on the river contracts and Ministry of Environment contribution to the dissemination and internationalisation of the river contracts [ I contratti di fiume in Italia (e oltreconfine). Il X Tavolo Nazionale dei Contratti di Fiume e il Contributo del Ministero dell’Ambiente alla diffusione e all’internazionalizzazione dei Contratti di Fiume]. Innsbruck, AT: Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention.

- Chiodelli, F. (2019). The dark side of urban informality in the Global North: Housing illegality and organized crime in Northern Italy. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43(3), 497–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12745

- Clement, F. (2008). A multi-level analysis of forest policies in Northern Vietnam: Uplands, people, institutions and discourses. PhD Thesis. Newcastle University Library.

- Clement, F. (2010). Analysing decentralised natural resource governance: Proposition for a ‘politicised’ institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Sciences, 43(2), 129–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-009-9100-8

- Clementi, F., Gallegati, M., & Gallegati, M. (2015). Growth and cycles of the Italian economy since 1861: The new evidence. Italian Economic Journal, 1(1), 25–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-014-0005-0

- Davoudi, S., Brooks, E., & Mehmood, A. (2013). Evolutionary resilience and strategies for climate adaptation. Planning Practice and Research, 28(3), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2013.787695

- Davoudi, S., Shaw, K., Haider, L. J., Quinlan, A. E., Peterson, G. D., Wilkinson, C., Davoudi, S., Fünfgeld, H., McEvoy, D., Porter, L., & Davoudi, S. (2012). Resilience: A bridging concept or a dead end? ‘Reframing’ resilience: Challenges for planning theory and practice interacting traps: Resilience assessment of a pasture management system in Northern Afghanistan urban resilience: What does it mean in planning practice? Resilience as a useful concept for climate change adaptation? The politics of resilience for planning: A cautionary note. Planning Theory & Practice, 13(2), 299–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2012.677124

- De Bernardinis, B., & Casagli, N. (2015). From the de Marchi Committee until today, between lightsand shadows [Dalla Commissione de Marchi a oggi, tra luci e ombre]. In Ecoscienza. Sostenibilità e Controllo Ambientale. Fragilitá del suolo e gestione degli eventi estremi, dalla cultura dell’emergenza a quella della prevenzione, Vol. 3 (pp. 32–35). Agenzia Regionale Prevenzione e Ambientale dell’Emilia-Romagna (ARPA).

- De Bruijn, K., Buurman, J., Mens, M., Dahm, R., & Klijn, F. (2017). Resilience in practice: Five principles to enable societies to cope with extreme weather events. Environmental Science & Policy, 70, 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.02.001

- De Leo, D. (2017). Urban planning and criminal powers: Theoretical and practical implications. Cities, 60, 216–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.09.002

- De Marchi Committee. (1970). Proceedings of the Interministerial Committee for the study of hydraulic works and soil defense [Atti della Commissione Interministeriale per lo studio della sistemazione idraulica e della difesa del suolo]. Rome, IT.

- De Moel, H., Van Alphen, J., & Aerts, J. C. J. H. (2009). Flood maps in Europe – Methods, availability and use. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 9(2), 289–301. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-9-289-2009

- Driessen, P. P. J., Hegger, D. L. T., Bakker, M. H. N., Van Rijswick, H. F. M. W., & Kundzewicz, Z. W. (2016). Toward more resilient flood risk governance. Ecology and Society, 21(4), 4. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08921-210453

- Fabrizi, C., Pico, R., Casolaro, L., Graziano, M., Manzoli, E., Soncin, S., Esposito, L., Saporito, G., & Sodano, T. (2015). Real estate industry, supply chain and credit companies: An assessment of the long recession effect [Mercato immobiliare, imprese della filiera e credito: Una valutazione degli effetti della lunga recessione]. Divisione Editoria e stampa della Banca d’Italia.

- Farcomeni, A. (2019). Power shift in flood risk management. Insights from Italy. In E. C. Penning-rowsell & M. Becker (Eds.), Flood risk management. Global case studies of governance, policy and communities (1st ed., pp. 58–69). Routledge.

- Florensa, M. C. (2004). Institutional stability and change. A logic sequence for studying. Paper presented at the Tenth Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study of Common Property (IASCP): The Commons in an Age of Global Transition: Challenges, Risks and Opportunities. Oaxaca, MX.

- Folke, C. (2006). Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Global Environmental Change, 16(3), 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.04.002

- Galletti, G. L., Delrio, G., De Vincenti, C., Curcio, F., De Angelis, E., & Grassi, M. (2017). Italia Sicura. National plan of measures and interventions, and financial plan for landslide and flood risk mitigation [Piano nazionale di opere e interventi e il piano finanziario per la riduzione del rischio idrogeologico]. Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri.

- Gallozzi, P., Dessì, B., Iadanza, C., Guarneri, E. M., Marasciulo, T., Miscione, F., Spizzichino, D., Rischia, I., & Trigila, A. (2020). ReNDiS 2020. Twenty years of ISPRA monitoring interventions of soil defence for landslide and flood risk mitigation [ReNDiS 2020. La difesa del suolo in vent’anni di monitoraggio ISPRA sugli interventi per la mitigazione del rischio idrogeologico]. ISPRA.

- Garofoli, G. (2016). The Italian economic development since the post-war period: Policy lessons for Europe. Working paper.

- Gersonius, B., Van Buuren, A., Zethof, M., & Kelder, E. (2016). Resilient flood risk strategies: Institutional preconditions for implementation. Ecology and Society, 21(4), 4. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08752-210428

- Goria, A., & Lugaresi, N. (2004). The evolution of the water regime in Italy. In I. Kissling-Näf & S. Kuks (Eds.), The evolution of national water regimes in Europe (pp. 265–291). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-2484-9_8

- Hajer, M. A. (1995). The politics of environmental discourse: Ecological modernization and the policy process. Clarendon Press.

- Holling, C. S. (1996). Engineering resilience versus ecological resilience. In P. C. Schulze (Ed.), Engineering within ecological constraints (pp. 31–44). National Academy Press.

- Hutchcroft, P. D. (2001). Centralization and decentralization in administration and politics: Assessing territorial dimensions of authority and power. Governance, 14(1), 23–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/0952-1895.00150

- Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale [ISPRA]. (2018). Territory. Processes and modifications in Italy [Territorio. Processi e trasformazioni in Italia]. Rapporto 296/2018.

- Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale [ISPRA]. (2020). Italy and the environment. Trend and regulations [Ambiente in Italia. Trend e normative]. Rapporto 93/2020.

- Jabareen, Y. (2013). Planning the resilient city: Concepts and strategies for coping with climate change and environmental risk. Cities, 31, 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.05.004

- Kingdon, J. W. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Little, Brown & Company.

- Kundzewicz, Z. W., Hegger, D. L. T., Matczak, P., & Driessen, P. P. J. (2018). Opinion: Flood-risk reduction: Structural measures and diverse strategies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(49), 12321–12325. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1818227115

- Leonardi, R., Nanetti, R. Y., & Putnam, R. D. (1981). Devolution as a political process: The case of Italy. Publius, 11(1), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.2307/3329647

- Lombardi, P. (2016). Urban landslide and flood risk between old and new competencies [La città ed il rischio idrogeologico tra vecchie e nuove competenze]. Il Piemonte Delle Autonomie.

- Lubitz, R. (1978). The Italian economic crises of the 1970s. International Finance Discussion Papers. https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/IFDP/1978/120/ifdp120.pdf.

- Massarutto, A. (1999). Italian water policies: The difficult transition from the policy of public infrastructure to the environmental policy [Le politiche dell’acqua in Italia: La difficile transformazione dalla politica delle infrastrutture alla politica ambientale]. In P. Faggi & L. Rocca (Eds.), Il governo dell’acqua tra percorsi locali e grandi spazi. Atti del Seminario Internazionale “Euroambiente 1998”, Portogruaro, 29 Aprile 1998. (pp. 75–102). University of Padova.

- Massarutto, A., De, C. A., Longhi, C., & Scarpari, M. (2003). Public participation in River Basin management planning in Italy. An unconventional marriage of top-down planning and corporative politics. HarmoniCOP project – Harmonising collaborative planning. Work package 4 – Final report. University of Udine.

- Meijerink, S. (2005). Understanding policy stability and change. the interplay of advocacy coalitions and epistemic communities, windows of opportunity, and Dutch coastal flooding policy 1945–20031. Journal of European Public Policy, 12(6), 1060–1077. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760500270745

- Meijerink, S., & Dicke, W. (2008). Shifts in the public–Private divide in flood management. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 24(4), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900620801921363

- Miceli, R., Sotgiu, I., & Settanni, M. (2008). Disaster preparedness and perception of flood risk: A study in an alpine valley in Italy. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(2), 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.10.006

- Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare [MATTM]. (2015). National strategy for climate change adaptation [Strategia Nazionale di Adattamento ai Cambiamenti Climatici].

- Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare [MATTM]. (2018). National plan for climate change adaptation [Piano Nazionale di Adattamento ai Cambiamenti Climatici].

- Moccia, F. D. (2020). INU in Campania Region between the two wars. An indirect influence on the origins of modern urban planning [L’INU in Campania tra le due guerre. Un’influenza indiretta alle origini dell’urbanistica moderna]. Istituto Nazionale di Urbanistica.

- Mysiak, J., Testella, F., Bonaiuto, M., Carrus, G., De Dominicis, S., Ganucci Cancellieri, U., Firus, K., & Grifoni, P. (2013). Flood risk management in Italy: Challenges and opportunities for the implementation of the EU floods directive (2007/60/EC). Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 13(11), 2883–2890. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-13-2883-2013

- Oosterberg, W., Van Drimmelen, C., & Van der Vlist, M. (2005). Strategies to harmonize urbanization and flood risk management in deltas. Proceedings of the 45th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: Land Use and Water Management in a Sustainable Network Society (pp. 1–31). Leibniz Information Centre for Economics.

- Osti, G. (2017). The anti-flood detention basin projects in Northern Italy. New wine in old bottles? Water Alternatives, 10(2), 265–282. https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/alldoc/articles/vol10/v10issue2/355-a10-2-5/file

- Ostrom, E. (1986). An agenda for the study of institutions. Public Choice, 48(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00239556

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

- Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton University Press.

- Ostrom, E. (2007). Institutional rational choice. An assessment of the institutional analysis and development framework. In P. A. Sabatier (Ed.), Theories of the policy process (2nd ed., pp. 21–64). Westview Press.

- Ostrom, E. (2014). Do institutions for collective action evolve? Journal of Bioeconomics, 16(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10818-013-9154-8

- Pahl-Wostl, C., Becker, G., Knieper, C., & Sendzimir, J. (2013). How multilevel societal learning processes facilitate transformative change: A comparative case study analysis on flood management. Ecology and Society, 18(4), 4. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05779-180458

- Palmieri, W. (2011). Environmental instability and disasters in Italy from unification until today [Per una storia del dissesto e delle catastrofi idrogeologiche in Italia dall’Unità ad oggi]. Quaderno dell'Istituto di Studi sulle Società del Mediterraneo. http://www.issm.cnr.it/personale/palmieri/pdf/QuadCatastrofiPostUnita.pdf

- Peters, B. G., Pierre, J., & King, D. S. (2005). The politics of path dependency: Political conflict in historical institutionalism. The Journal of Politics, 67(4), 1275–1300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2005.00360.x

- Petrow, T., Thieken, A. H., Kreibich, H., Merz, B., & Bahlburg, C. H. (2006). Improvements on flood alleviation in Germany: Lessons learned from the Elbe flood in August 2002. Environmental Management, 38(5), 717–732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-005-6291-4

- Pierson, P. (2000). Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. American Political Science Review, 94(2), 251–267. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586011

- President of the Council of the Ministers. (2019). ProteggItalia. National plan for landslide and flood risk mitigation, restoration and protection of environmental resources [Piano nazionale per la mitigazione del rischio idrogeologico, il ripristino e la tutela della risorsa ambientale].

- President of the Italian Republic. (1952). Law 19 March 1952, no. 184: Illustrative plan for water control and annual report of the Ministry of Public Works [Legge 19 marzo 1952, n. 184: Piano orientativo ai fini di una sistematica regolazione delle acque e relazione annua del Ministero dei lavori pubblici]. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.83 del 07-04-1952.

- President of the Italian Republic. (1962). Law 25 January 1962, no. 11: Implementation plan for natural watercourses management [Legge 25 gennario 1962, n. 11: Piano di attuazione per una sistematica regolazione dei corsi di acqua naturali]. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.161 del 27-06-1962.

- President of the Italian Republic. (1977). Decree of the President of the Italian Republic 24 July 1977, no. 616. Implementation of art. 1, Law 22 July 1975, no. 382 [Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica 24 luglio 1977, n. 616: Attuazione della delega di cui all’art. 1 della legge 22 Luglio 1975, n. 382]. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.269 del 03-10-1977.

- President of the Italian Republic. (1986). Law 8 July 1986, no. 349. establishment of the ministry of environment and regulations concerning environmental damage [Legge 8 luglio 1986, n. 349. Istituzione del Ministero dell’ambiente e norme in materia di danno ambientale]. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.162 del 15-07-1986.

- President of the Italian Republic. (1989). Law 18 May 1989, no. 183. Regulations concerning organisational and functional aspects of soil defence [Legge 18 maggio 1989, n. 183. Norme per il riassetto organizzativo e funzionale della difesa del suolo]. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.120 del 25-05-1989- Suppl. Ordinario no. 38.

- President of the Italian Republic. (1992). Law 24 February 1992, no. 225. Establishment of the national civil protection service [Legge 24 febbraio 1992, n. 225. Istituzione del servizio nazionale della protezione civile]. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.64 del 17-03-1992.

- President of the Italian Republic. (1998). In Law 3 August 1998, no. 267. Conversion into law with modification of the Decree-Law 11 June 1998, no. 180 concerning urgent measures for landslide and flood risk prevention and in support of the areas affected by landslides in Campania region [Legge 3 agosto 1998, n. 267. Conversione in legge, con modificazioni, del decreto-legge 11 giugno 1998, n. 180, recante misure urgenti per la prevenzione del rischio idrogeologico ed a favore delle zone colpite da disastri franosi nella regione Campania]. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.183 del 07-08-1998.

- President of the Italian Republic. (2000). Law 11 December 2000, no. 365. Conversion into law with modification of the Decree-Law 12 October 2000, no. 279 concerning urgent measures for very-high landslide and flood risk areas and on matters concerning the civil protection and in support of the areas affected by landslide and floods in Calabria region in September and October 2000 [Legge 11 dicembre 2000, n. 365. Conversione in legge, con modificazioni, del decreto-legge 12 ottobre 2000, n. 279, recante interventi urgenti per le aree a rischio idrogeologico molto elevato ed in materia di protezione civile, nonché a favore delle zone della regione Calabria danneggiate dalle calamità idrogeologiche di settembre ed ottobre 2000]. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.288 del 11-12-2000.

- President of the Italian Republic. (2006). Legislative decree 3 April 2006, no. 152. Regulations concerning environmental matters [Decreto legislativo 3 aprile 2006, n. 152. Norme in materia ambientale]. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.88 del 14-04-2006- Suppl. Ordinario no. 96.

- President of the Italian Republic. (2010). Legislative decree 23 February 2010, no. 49. Transposition of the Floods Directive 2007/60/EC concerning flood risks assessment and management [Decreto legislativo 23 febbraio 2010, n. 49 Attuazione della direttiva 2007/60/CE relativa alla valutazione e alla gestione dei rischi di alluvioni]. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana n.77 del 02-04-2010.

- Rainaldi, F. (2009). Water management in Italy: From spatial planning to river basin management [Il governo delle acque in Italia: Dalla pianificazione territoriale al basin management]. In XXIII Convegno SISP Roma, Facoltà di Scienze Politiche LUISS Guido Carli, September 17–19, 2009 (pp. 1–28). LUISS Guido Carli.

- Rainaldi, F. (2010). Water management in Italy and UK: A policy change analysis [Il governo delle acque in Italia e Inghilterra: Un’analisi del policy change]. PhD Thesis. Alma Mater Studiorum.

- Regione Lombardia, Regione Piemonte, Autorità di Bacino del Fiume Po, Coordinamento Nazionale Agende 21 Locali. (2012). National charter for the river contracts [Carta Nazionale dei Contratti di Fiume]

- Remmelzwaal, A., & Vroon, J. (2000). Werken met water, veerkracht als strategie [Working with water: Resilience of strategy]. RIZA/RIKZ.

- Renn, O., Klinke, A., & Van Asselt, M. (2011). Coping with complexity, uncertainty and ambiguity in risk governance: A synthesis. Ambio, 40(2), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-010-0134-0

- Rusconi, A. (2010). Water and landslide and flood risk. The design of the river basin plans for water and spatial management [Acqua e assetto idrogeologico. La progettazione dei piani di bacino per la gestione delle acque e del territorio]. DEI Tipografia del Genio Civile.

- Sayers, P. B., Hall, J. W., & Meadowcroft, I. C. (2002). Towards risk-based flood hazard management in the UK. Proceedings of the ICE – Civil Engineering, 150(5), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1680/cien.2002.150.5.36

- Scolobig, A., Linnerooth-Bayer, J., & Pelling, M. (2014). Drivers of transformative change in the Italian landslide risk policy. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 9, 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.05.003

- Sorrentino, R. (2019). Euro: Findings from the first 20 years of single currency in Italy in 10 graphs [Euro: Cos’è successo all’ Italia nei primi 20 anni di moneta unica,in 10 grafici]. Il Sole 24 Ore. https://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/come-e-cambiata-l-economia-italiana-primi-vent-anni-dell-euro-ACGqP8E

- Testella, F. (2011). Normative evolution concerning landslide and flood risk since Law 183/1989 to the Floods Directive (2007/60/EC) and the legislative Decree 49/2010 [Evoluzione normativa sul rischio idrogeologico dalla Legge 183/1989 alla Direttiva Alluvioni (2007/60/CE) e il Decreto Legislativo 49/2010]. Centro Euro-Mediterraneo per i Cambiamenti Climatici.

- Trigila, A., Iadanza, C., Bussettini, M., & Lastoria, B. (2018). Environmental instability in Italy: Hazard and risk indicators. Edition 2018. Report 287/2018. [Dissesto idrogeologico in Italia: Pericolosità e indicatori di rischio. Edizione 2018. Rapporto 287/2018]. ISPRA.

- Van Buuren, A., Ellen, G. J., & Warner, J. F. (2016). Path-dependency and policy learning in the Dutch delta: Toward more resilient flood risk management in the Netherlands? Ecology and Society, 21(4), 4. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08765-210443

- Van den Hurk, M., Mastenbroek, E., & Meijerink, S. (2014). Water safety and spatial development: An institutional comparison between the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Land Use Policy, 36, 416–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.09.017