ABSTRACT

This study conducted an in-depth systematic review of literature to explore the context of water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH) sustainability and resilience in refugee communities. Our results indicate growing concerns, given the two-decade waiting period for refugees to achieve repatriation/integration into host communities, and the bulk of their accommodation is largely in the Global South. This makes the sustainability of WaSH increasingly complex and depends on understanding the roles and interdependences among the factors in each specific refugee camp, and recognizes that it is not ‘one-size-fits-all’ solutions and the sustainability of one camp might not be suitable for other camps.

Introduction

The number of people forcibly displaced, both within their country of residence as internally displaced persons (IDPs) or crossing borders as refugees, due to disasters (both man-made and natural), war, conflicts and violence, dramatically increased over the last decade. The UCL Lancet Commission on Migration and Health highlights that migrants, including forcibly displaced people, are more often discriminated against and denied access to health services compared with local populations (Abubakar et al., Citation2018), and their health needs are often unmet (Miliband & Tessema, Citation2018). Together, the increasing numbers of refugees and health disparities put enormous pressure on the ability of humanitarian and development organizations (HDOs) to provide basic services, including safe access to clean water for sanitation and hygiene (WaSH), to minimize public health risks. In 2020, 82.4 million people (42% children under 18 years of age) were displaced, despite restrictions due to the Covid-19 pandemic and border closures, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees’ (UNHCR) Global Trends Report (UNHCR, Citation2020), an increase from about 79.5 million displaced people due to similar causes in 2019. The UNHCR responded to internal displacement events due to conflict and wars in 34 countries in 2020, which increased the number of IDPs by 30% compared with 2019 and provided emergency services in response cyclones and flooding devastation in Central American and African countries, which are also grappling with internal conflict and political instability. The recent outbreak of Covid-19 worldwide and the re-emergence of Ebola in African countries have highlighted how fragile and unsustainable WaSH and other service delivery systems are in many developing countries (Hannah et al., Citation2020), with heightened vulnerability in refugee settings, especially in camps. The people living in camps often lack safe access to clean water in adequate quantities, have a shared toilet system, and the health of many is already stressed from water-borne diseases, such as cholera and diarrhoea, exacerbating vulnerabilities (Betts et al., Citation2021; Cooper et al., Citation2020; Shackelford et al., Citation2020). For example, in Kutupalong (the largest Rohingya refugee camp in Bangladesh) often one toilet is shared by 28–32 people (Akhter et al., Citation2020, p. 16) compared with the SPHERE standard of one toilet per 20 people. Adopting critical measures including washing hands with soap regularly, cleaning of hand-contact surfaces and of clothing, towels and bedding on hot wash cycles, self-quarantine and social distancing to prevent these disease outbreaks seems impossible in the context of refugee camps, even in highly developed countries such as the UK and France (Dhesi et al., Citation2018; The Guardian, Citation2021). Indeed, in the UK, among other factors, inadequate provision of facilities for asylum seekers was responsible for significant Covid-19 clusters due to overcrowding, poor hygiene and sanitation facilities, using facilities that had previously been designated unfit for the military (The Guardian, Citation2021).

Earlier research found that approximately three-quarters of deaths among residents of refugee camps are caused by communicable diseases that are spread due to overcrowded settlements (Connolly et al., Citation2004). Therefore, public health-related impacts from natural or man-made hazards in often-overcrowded refugee camps are more devastating than in any other setting if not prepared for or mitigated through sustainability planning. This is becoming urgent as the World Health Organization (WHO, Citation2019) states that most countries can expect to experience at least one large-scale emergency every five years, in addition to increased frequency of both small (disease outbreaks, fire) and large (monsoon floods, cyclone) seasonal and man-made disasters and emergencies, with impacts including loss of life, disability and significant loss of livelihoods (WHO, Citation2019). Simultaneously, it has been estimated that by 2050 there will be more than 200 million environmental refugees globally due to the impacts of climate change (Brown, Citation2008) such as sea-level rise, water security issues, and increased drought/flooding and extreme weather events. Ensuring safe access to WaSH and other basic services to millions of refugees in this context will become extremely challenging and might jeopardize the goal of a sustainable future.

Refugee camps (for a definition and alarming facts, see Appendices A and B) are designed to meet the most basic needs – food, water, shelter, medical treatment – during emergencies and are an integral part of UNHCR emergency operations to provide basic services to refugees or IDPs. Camps are considered as temporary shelters before any viable long-term solution (such as repatriation/integration into the hosting community) to displacement can be achieved. The defining feature of camps according to the UNHCR is ‘some degree of limitation on the rights and freedoms of refugees, such as their ability to move freely, choose where to live, work or open a business, cultivate land or access protection and services’ (UNHCR, Citation2021, p. 1). The ‘alternatives to camps’ approach (see Appendix A) is defined in the UNHCR policy as strategies to remove these restrictions so that refugees’ dignity and well-being can be restored. This includes integrating refugees with the community upon their arrival or as soon as possible thereafter. It is acknowledged that alternatives to camps are complicated and require years of strategic planning and facilitation by host countries to achieve the necessary integration, alongside investment of substantial time, resources and international efforts to achieve (Idris, Citation2017; Tull, Citation2017). However, ‘alternatives to camps’ must be made viable as a matter of urgency through the establishment of coherent policies across HDOs and human rights groups, given that camps are home to growing numbers of displaced people, typically in areas that themselves have systemic challenges in terms of infrastructure and poverty.

In reality, many camps have been operating for decades without any effective solutions and face further difficulties in providing access to WaSH services due to the ageing of infrastructure, sudden onset of disaster and funding limitation on maintenance (Akhter et al., Citation2020; Cooper et al., Citation2020; Shackelford et al., Citation2020). The oldest camp in history, known as ‘Cooper’s camp in West Bengal’, was established to provide shelter to people displaced due to the 1947 partition of so-called British India into India and Pakistan (Finch, Citation2015), and in 2015 it was reported as still being home to about 7000 people. Recent data highlight that just four large camps together accommodate more than 1 million refugees and IDPs (UNHCR, Citation2021), and almost 86% of the total refugees (estimated 82.4 million refugees in 2021) and IDPs are hosted by developing countries (UNHCR, Citation2021) with 65% of camps located in climate hotspots (UNHCR, Citation2001) (Appendix A). Therefore, ensuring provision of the basic services such as WaSH to camps (or alternatives to camps) is crucial, as is ensuring the sustainability and resilience of these services to sudden onset of disaster or another emergency. This review unpacks how the sustainability and resilience of WaSH interventions can be achieved and whether the provision of services to camps can also be done in a manner that benefits the surrounding local communities.

Theory of change, multisectoral, multidisciplinary and system-wide approach for sustainability and resilience

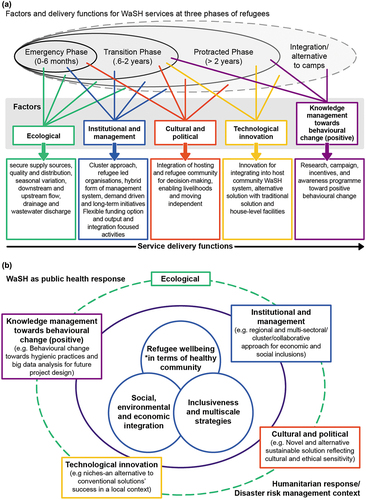

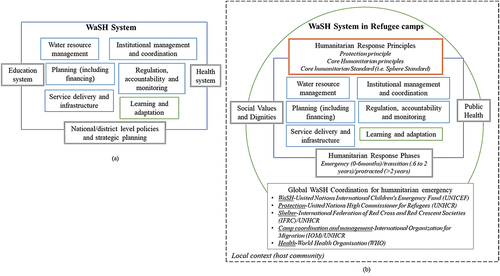

A sustainable and resilience-focused WaSH system requires evaluating risk management plans and implementing strategies at different levels (macro, meso and micro) and supporting, strengthening, and restoring local capacities during protracted crises and in post-disaster or post-conflict periods (Akhter et al., Citation2020; Day et al., Citation2020; Howard et al., Citation2020). According to the theory of change, the different blocks necessary for developing an effective WaSH system (Gensch & Tillett, Citation2019; Huston & Moriarty, Citation2018) are shown in ); however, this was designed for the general context (where national/international standards for WaSH services exist). Refugee camps often use the SPHERE standards or WaSH manuals developed by UNICEF/UNHCR for emergency situations, where resilience or sustainability might not be the major focus. ) explains the complexity and contextual differences in developing a WaSH system in refugee camps compared with the general context. This indicates that for a complex system such as WaSH, critical framing is required to reduce public health risks which requires disaster risk assessment, preparedness-planning and community-driven responses (Betts et al., Citation2021; Spiegel et al., Citation2019), and an integrated approach to implement and monitor risk-informed and climate-sensitive plans (Mizutori, Citation2020).

Figure 1. Building blocks for the WaSH system in general (a) and for the refugee context (b).

Indeed, the sustainability and resilience framings have indicated a critical relationship between public health and disaster risk reduction (DRR) for many decades. The first international policy framework in DRR – the Hyogo Framework of Action (HFA) (2005–15) – started to connect public health with disaster risk management scope. The Sendai Framework for DRR (2015–30) replaced the HFA and introduced ‘health resilience’ and ‘building back better’ in line with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) commitment of ‘leaving no one behind’. All these frameworks entail the critical relation between DRR and public health response with a key focus on the resilience of health infrastructure and ensuring equal access to WaSH services. The recent development of the ‘Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management (EDRM) Framework’ by the WHO (Citation2019) further signifies this critical relation and the future projection of changing public health responses and the utmost importance of system-wide approaches and disaster prevention, preparedness and readiness. This framework adopted a set of core principles and approaches to guide policy and practice, including a risk-based approach, comprehensive emergency management (prevention, preparedness, readiness, response and recovery), an all-hazards approach with a focus on inclusive-, people- and community-centred approaches. Together, these frameworks point towards multi-sectoral and multidisciplinary collaboration, and incorporation of whole-of-health systems-based approaches and ethical considerations, noted also by policy practitioners and scholars as being important for the sustainability of the service-delivery system including WaSH (Chan et al., Citation2018; Spiegel et al., Citation2019; WHO, Citation2019).

Research has evidenced that despite both disaster science experts and public health professionals acknowledging public health as a critical determinant of DRR (Chan et al., Citation2018), responses towards mitigating public health hazards in high-density areas, such as refugee camps, tend to focus on rapid public health assessments and ad-hoc or short-term solutions to control risks rather than looking for the underlying factors and overall capacity of the system to cope in the long term (Spiegel et al., Citation2019). Here capacity refers to the combination of all strengths, attributes and resources available within a community, society or organization that can be used to achieve agreed goals (WHO, Citation2019). However, the paradox of prevention (including the inverse law whereby most cases of a disease come from a population at low or moderate risk of that disease, and only a minority of cases come from the high-risk population for the specific disease) and preparedness studies underscore these approaches and state that current short-term focused service-delivery models do not benefit those who need them most (Day et al., Citation2020; Nicole, Citation2015). The contemporary paradigm of humanitarian assistance is now shifting towards a more sustainable and resilient approach to ensure that refugees have equal access, dignity and well-being as local populations. Such a shifted paradigm recommends that governments and aid agencies carefully consider both the refugee and host communities who are exposed to resource constraints including increasing public health and environmental risks (Araya et al., Citation2019; Tafere, Citation2018) and those selected solutions should enhance conditions for both groups. In light of such policy transformation, this review explores the critical linkages from the different factors and building blocks of WaSH that reduce the public health burden, with an emphasis on reducing vulnerability and developing capacity to cope with disaster and with the impact of climate change in different geographical locations.

Research aim and objectives

It is critical to understand the coherence across WaSH interventions, public health hazard and disaster risk-reduction strategies to deliver sustainable and resilient systems for refugees and other vulnerable groups, such as high-density communities living in slums or other urban areas, and to examine the context, factors and capacity development that are needed to effectively deliver WaSH. Therefore, this review aims to understand if and how coherence across WaSH interventions, public health hazards and disaster risk-reduction strategies in refugee camps can deliver a sustainable and resilient system for the immediate benefit of the displaced persons and the longer term benefit of refugees and their host communities. The following research objectives were formulated to achieve this aim:

To unpack the critical factors and outcomes related to the WaSH interventions responsible for the vulnerability and capacity of the public health system in relation to refugee well-being.

To identify the barriers and opportunities in WaSH interventions that impede or support the minimization of public health risks in refugee camps.

To determine to what extent evidence suggests that WaSH interventions can be made sustainable and resilient in camps and can offer opportunities for the integration of refugee and host communities for future benefit.

The outputs of the systematic review (of the peer-reviewed literature and international development organizational reports) will inform practitioners of the factor interdependencies, support development of capacity and resilience, and provide evidence of the economic and public health benefits of risk-informed and sustainable WaSH services in refugee settings.

Research methods

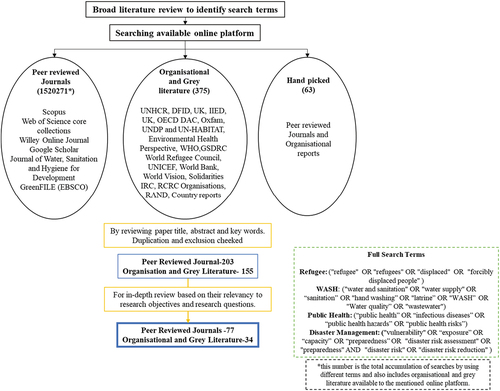

To address the study objectives, a systematic literature review was conducted using relevant search keywords in the available online research platforms (see for details). This review process followed the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta analyses (PRISMA) approach and checklist to structure the content and discussion, which is added as supplementary data to this paper. The PRISMA approach provides a structural guideline for ensuring the quality of the review (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the systematic approach to identifying relevant literature for critical review.

Literature identification

We searched several platforms containing peer-reviewed journal articles along with the grey (not peer reviewed and available online) and organizational literature using keywords such as WaSH, public health risk, disaster risk reduction and refugees (search formulas and specific search engines are provided in the supplemental data online). The organizational literature indicates reports published by an organization (e.g., UNHCR, World Bank, WHO). A description of the search and inclusion/exclusion rationale is presented in . Inclusive strategies for searching the relevant literature used different keywords (). Search queries were time limited to after 2001 (i.e., after the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were adopted) to 2021 (20 years). Database searches were conducted in March and April 2021 and repeated in June 2021 for any addition to the relevant topics.

Table 1. Exclusion criteria for the systematic scoping review.

Selection of articles and data extraction

To understand the critical link across public health hazards, WaSH intervention and disaster risk-reduction strategies, a two-step screening process was developed. The initial screening vetted papers for their applicability to refugee settings and WaSH systems. In the secondary screening, studies were reviewed for three core ideas – public health hazard risk assessment, disaster management scope assessment and WaSH intervention assessments.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria table

This research explored literature that deals with refugees in any phase of their displacement. Although the focus is on the protracted phase where people live in the camps or temporary shelters for more than two years, other phases were also looked at to understand how WaSH interventions include risk assessment and other disaster management strategies. WaSH services, including water quality, communicable diseases outbreak due to failure or quality deterioration of the WaSH facilities, faecal sludge management and drainage, were explored. A technology focus and other engineering development topics were excluded from the search as significant engineering projects are not generally available in a camp context, although they could in future become a key aspect of transitioning existing camps towards sustainable long-term settlements as part of an ‘alternatives to camps’ strategy. For example, recent technological developments towards solar desalination and waste treatments that do not require centralized infrastructure could be part of environmentally sustainable settlement (alternative to camp) solutions.

Initial screening

To ensure consistency in the screening process, the same search strategies were implemented across all databases and extracted titles, and publications were excluded based on the criteria outlined in . Initial screening was conducted using the titles and abstracts of publications (provided with a unique ID) and compiling them into a single Excel spreadsheet by removing duplicate titles. For a study to be included in the full-text review, it had to have an explicit focus on water, sanitation and hygiene, or the WaSH sector, in a refugee camp or temporary settlement for a displaced population living there for more than two years.

Second screening

To accurately characterize the linkage across WaSH services, public health risks and disaster management, the review examined three key aspects of each study that met the primary screening criteria above: (1) interrelated factors for developing WaSH; (2) barriers or challenges in WaSH implementation; and (3) case studies with evidence to recommend or assess sustainable WaSH delivery.

Key features of the literature search result, adopted research methods and dataset

The literature search resulted in 276 articles from the total cumulative search of 1,520,271 items and 63 from handpicked searches that were potentially eligible for review. Of these articles we eliminated duplicates and those not relevant to the research objectives, resulting in 203 articles considered eligible for primary screening (). After reviewing the articles for their applicability to WaSH, public health and DRR as described in the third section, 77 full articles and 34 organizational reports were obtained from the secondary screening.

The reviewed documents adopted several research methods and analytical lenses. The methods are diverse, consisting of a mix of qualitative or quantitative approaches. A number of techniques were adopted for data collection, including surveys, cross-sectional surveys, participatory data-collection techniques including key informants’ interviews, focus group discussion and semi-structured interviews. Epidemiological and statistical analyses were the most common, with algorithm-based analyses for decision-making or choosing the appropriate technology for WaSH-related interventions also noted, alongside composite scoring methods, frameworks, structured observations, the logic model for comprehensive risk profiling, techniques such as Geographic Information System (GIS), remote sensing, indexing or indicator-based analysis, nexus thinking, retrospective analysis, chemical analysis, systematic and desk-based review techniques, descriptive analysis using databases from relevant organizations (e.g., UNHCR Health Information System, EM-DAT), meta-analysis, rapid environment assessments/environmental impact assessments, Delphi approach and spatial analysis. Appendix C shows the key datasets with characteristics that were identified as being crucial for refugee WaSH research. As this study presents a systematic review, providing a percentage of papers addressing the key issues discussed is important to indicate the academic focus and gaps in the research study areas.

Results and discussions

Transformed policies, varied disciplinary lens and diverse geography to integrate disaster risks and public health responses

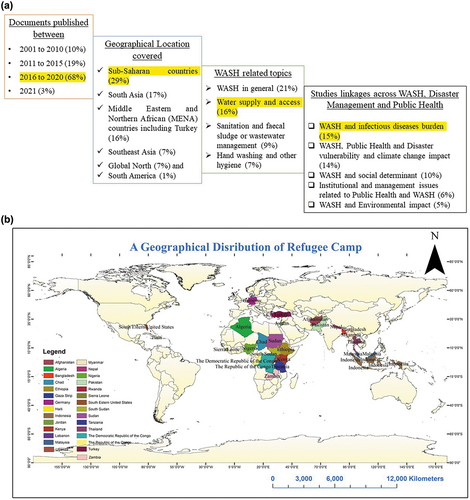

The review revealed that increasing academic focus on WaSH in refugee camps after 2015 (68%) is compared with the previous half-decade (2011–15, 19%). Largely these literatures emphasizing WaSH as a critical preventive measure to public health and disaster risk management (DRM) (). This increasing WaSH literature after 2015 coincides with the launch of key global directives such as SDGs and the Sendai Framework for DRR in 2015 emphasizing ‘health resilience’ and ‘leaving no one behind’. These global commitments have triggered a transformation in policy and regulatory guidelines at different scales of implementation that integrate DRM and public health preparedness through WaSH interventions with a focus on refugee well-being, health and the right to a dignified life (). However, research exploring such interdependencies and influences across different scales (local, regional and national) of policy harmonization is still extremely sparse.

Table 2. Timeline showcasing international and national directives related to refugees and WaSH at different implementation levels.

In line with the SDGs (i.e., SDG 6: access to water and sanitation systems for all; SDG 10: reduced equality; and SDG 11: sustainable cities and communities) and the Sendai Framework for DRR connecting health and resilience, water supply and access in a refugee context was found to be highlighted in the most reports (16%), with an increasing contemporary focus on sanitation, in particular faecal sludge management (9%) and hand hygiene (7%). From the epidemiological context, 15% of the reviewed documents looked at overall gaps in WaSH found to increase the burden of diseases. Epidemiological studies published before 2010 aimed to understand the prevention and mitigation measures to reduce morbidity and mortality from various vector-borne diseases, such as cholera, diarrhoea and respiratory infections (Cronin et al., Citation2008, Citation2009; Shultz et al., Citation2009). The contemporary studies are becoming more specific using a different lens to analyse the vulnerability and public health dimensions of the affected population while understanding its resilience and sustainability from the disaster management viewpoint (14%). In addition to prioritizing the quality and quantity of the water and sanitation services in camps, hygiene – including hand, oral and menstrual – has received attention (7%). Furthermore, contemporary studies used the gendered lens to estimate vulnerability (especially for women, elderly and disabled to miss the benefit of the interventions) to improved health and well-being in a refugee community (Feinberg et al., Citation2021; Nelson et al., Citation2020; Schmitt et al., Citation2021).

Despite the adoption of the Framework for Assessing Monitoring and Evaluating the environment in refugee-related operations (FRAME) in 2009 (UNHCR and CARE) and establishment of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) in 2015 advocating for a healthy environment as a basic right for refugees, only a few (5%) of the reviewed documents used the ‘right to a healthy environment’ as an analytical lens for research, and the literature reported a stark difference in refugees’ access to a healthy environment compared with host communities no matter whether the camps are located in the Global North or Global South (Araya et al., Citation2019; Day et al., Citation2020; Dhesi et al., Citation2015; Yamamoto et al., Citation2017). This lack of environmental focus poses a huge gap in the literature, in particular the lack of recognition of the role of environmental health in camp situations which urgently requires deeper exploration.

Overall, the literature review found that Sub-Saharan African countries (29%) were the most researched, while other regions captured in the literature include South Asian countries (17%) and Middle East and North African countries including Turkey (MENAT) (16%) (). MENAT countries, as per the rest of the developing world, are yet to achieve their commitments and targets defined by the SDGs, which have a deadline by 2030.

Figure 3. (a) Key attributes in reviewed documents, as a percentage, where the total number of documents is n = 111; and (b) geographical distribution of refugee host countries.

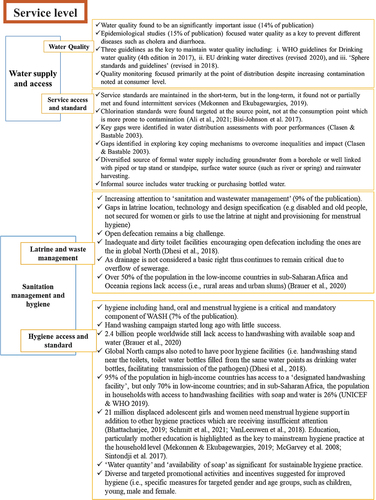

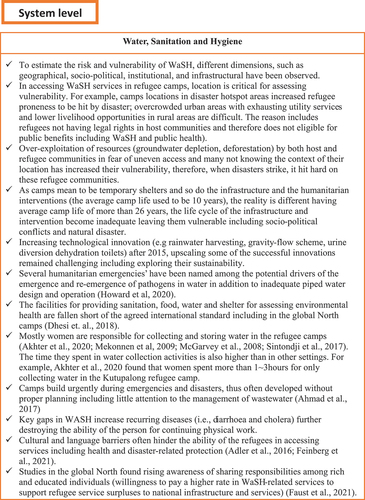

As part of prevention measures from a public health perspective and a basic right from the humanitarian context, establishing water and sanitation infrastructure was key, and the literature looked at a different component of WaSH (i.e., supply water quality and quantity, latrine use, hand washing, faecal sludge management) at both system and services levels. Appendix D showcases some of the WaSH key information at both service and system levels identified through this review.

Shifted implementation approach, priorities, and timeline

The review outcomes highlight changes in priorities, approach and focus of humanitarian responses including WaSH in refugee camps over time (2000–21) through the three phases of refugees’ life cycle, that is, emergency (0–6 months), transitional (six months–two years) and protracted (more than two years) (Cooper et al., Citation2020; Shackelford et al., Citation2020; Zaman et al., Citation2020). While our study focused on the protracted phase, a few studies critical to understand WaSH services in camps which looked at the emergency and transitional phases are also included in our analysis. The changes captured through this review are presented in .

Box 1. Shifting approaches and priorities on humanitarian responses including WaSH from 2000 to 2021.

Research before 2010 (10%) focused on integrated and sustainable practices targeting MDGs in refugee settings. The targeted projects had an epidemiological context and focused on understanding disease burdens based on specific outbreaks. Some identified the ‘hardware approach’ such as improved health infrastructure as key to reducing public health risks, whereas others indicated that a ‘soft approach’ such as campaigns and awareness programmes were more beneficial. For example, Cronin et al. (Citation2009) found improved medical access in the refugee camps as the reason for lower mortality estimates despite a higher estimate of diarrhoeal outbreaks in the refugee camps in seven Sub-Saharan countries relative to the surrounding local populations in 2005. By contrast, Shultz et al. (Citation2009) credited an educational and awareness programme for improving hygiene practices for ‘new arrival refugees’ as this group is most affected by cholera outbreaks in Kenyan refugee camps.

Publications between 2011 and 2015 (19%) largely continued to explore sustainable and sensitive infrastructure designs. These studies analysed behavioural change to mainstream hygiene practice (Atuyambe et al., Citation2011; Hamid et al., Citation2015; Mahamud et al., Citation2012; Phillips et al., Citation2015), understanding the social context of public health and WaSH services where community inclusions and cultural diversity are suggested as critical (Marlowe, Citation2013; Vujcic et al., Citation2015). A few studies investigated water-quality challenges regarding social and cultural behaviours (i.e., taboos and misbeliefs) and suggested alternative solutions for wastewater such as faecal sludge management as a way towards achieving sustainable outcomes. Publications (68% + 3% = 71%) from 2016 to 2021 have demonstrated increasing understanding on the emergence of niches (novel and innovative approaches as alternatives to existing solutions), such as rainwater harvesting, urine diversion dehydration toilets and solar-powered desalination which are sensitive and culturally appropriate to the context of refugee communities (). This increasing tendency within contemporary research towards social and cultural sensitivity alongside technological innovation further captured a growing awareness of refugee issues by the Global North. This could be related to the higher intake of refugees and asylum seekers by Global North countries, such as Germany, the UK, the United States and Australia (Araya et al., Citation2019; Dhesi et al., Citation2018, Citation2015; Feinberg et al., Citation2021).

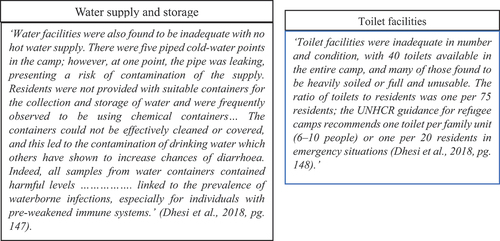

Box 2. Example of water and sanitation facilities in the Global North.

4.3 ‘Well-being’ as the key driver for assessing vulnerability and capacity

Within the observed timeline (before 2010, 2011–15 and 2016–21) for understanding the shifting approaches and research priorities on WaSH implementation, this review identified ‘refugee well-being’ as the key driver of most studies, where the term ‘well-being’ is used interchangeably with health (Feinberg et al., Citation2021; Schmitt et al., Citation2021) and refers to the state of a healthy community (i.e., improved capacity) as opposed to a vulnerable population (Akhter et al., Citation2020; Nelson et al., Citation2020). From a public health viewpoint, well-being refers to both mental and physical health, resulting in more holistic approaches to disease prevention and health promotion (Diener, Citation2000; Eid, Citation2008) by reducing suffering and vulnerability of affected communities through developing their capacity to adapt and learn (Leaning et al., Citation2011). Thus, the balance between vulnerability and capacity will ensure the well-being and resilience of the refugee community. Further suggestions from the literature are to consider economic, social, developmental (such as education) activity, emotional and life satisfaction/well-being while investigating different types of vulnerability (i.e., social, environmental or cognitive; Diener, Citation2000; Eid, Citation2008).

In the context of well-being and capacity as opposed to vulnerability, this research further found that there has been limited exploration of capacity in health research from a developing country context. The reasons identified include the fact that these countries are already stressed due to ‘frequent changes in economic development plans, limited opportunity to connect with international policymakers, scarce research funding, and a limited number of researchers compared with developed countries’ (Jang et al., Citation2021, p. 113). The authors further recommended implementing a disaster and health surveillance system to establish a baseline against which to understand the health impact of disasters and to identify intervention opportunities. Epidemiological studies focused on the benefit of wide-range vaccination programmes in addition to WaSH infrastructure have also been recommended; however, the combination of poverty and conflict or natural disaster poses more damage to these refugee communities or IDPs. There remain capacity gaps in the health infrastructure and support, within coordination of disaster response (at local, regional and international levels) and in terms of the necessary economic and social support to support refugees. From the DRR dimension, studies reported limitations or barriers inside camps including the fact that building permanent or semi-permanent structures for evacuation, such as cyclone shelters, is prohibited, and observed that when disasters strike, sometimes the national response strategies or appeals did not include refugee communities (Akhter et al., Citation2020; Zaman et al., Citation2020. For instance, the need-assessment report produced by the inter-sector coordination group (Bangladesh governmental agencies and UN agencies) prohibits building cyclone shelters (permanent or semi-permanent) in camps at Kutupalong in Cox’s Bazar, which is very prone to cyclone and storm surge floods (IOM, Citation2019; Zaman et al., Citation2020). This also increases refugee community vulnerability and exposures to natural disasters. provides a schematic of the need for coherence across disaster management, public health and WaSH, captured through this review.

Figure 4. Schematic presentation of the need for coherence across disaster management, public health and WaSH.

In terms of well-being, capacity and vulnerability, the condition of refugee camps in the Global North is not much different from those in the Global South. A study in the Calais Jungle camp (officially Camp de la Lande) in France found very similar results in terms of its failure to meet the standard provision requirements and its struggle to continue providing WaSH services to the refugees. shows quotations from the author’s own descriptions and experience from research performed in the Calais Jungle.

These findings are similar to the developing country context, and the Calais Jungle, intended as a temporary shelter for refugees and officially reported as removed in late 2016, in practice is still home to over 1000 refugees (Sawada et al., Citation2011). In other developed countries that are providing quality services to refugees (Van der Helm et al., Citation2017; Zaman et al., Citation2020), the numbers of refugees they can accommodate are small, and these are the exception rather than the rule, typically repurposing existing facilities such as schools, military dormitories or hospitals where WaSH facilities are already in place. Despite such WaSH arrangements, Covid-19 outbreaks were noted in temporary shelters in the UK due to overcrowding, poor hygiene and sanitation facilities, using unfit facilities designed for the military (BBC News, Citation2021), raising questions about how safe the WaSH facilities were towards ensuring public health preparedness.

Debate around camps or alternatives to camps for integration and sustainability

Despite camps or temporary shelters being a critical component of the operation of humanitarian responses for refugees for decades (since the 1940s), it has been acknowledged that this approach is not sustainable (largely services and infrastructures are found unsuitable or fragile after a few years) and there is increasing concern regarding public health for refugees and surrounding inhabitants. As camps are not ideal living conditions, for example, Khan et al. (Citation2020) described that:

the average number of people per household as 4.5. Almost all live in small makeshift shelters of 14 m2 built from bamboo and tarpaulins, with limited access to clean-water and sanitation and most sleep on plastic paper spread over the muddy floor in their tents. (p. 1)

In these circumstances, maintaining even minimum hygiene is challenging, and any infectious disease outbreak has the potential to kill thousands of people; some refugees choose to take their chances outside camps and thus there are large groups of refugees floating in cities or rural areas as illegal immigrants, further increasing their vulnerability. The alternatives to camps, on the other hand, requires society to enable more independent movement of refugees, including the provision of social integration and economic stability, which requires a healthy community and economy (Price, Citation2017).

In the approaches to integration (i.e., mainstreamed, or shared access to both the social and infrastructural services) described in the UNHCR policy of ‘alternatives to camps’, WaSH is a very viable option if built-in from the beginning of planning and implementation of refugee interventions. The UNHCR advocates for refugees’ access to local services and for mainstreaming the management of refugee WaSH services into local water and sanitation (governance) structures. For example, Nepal has been hosting Bhutanese refugees for more than 24 years, accommodating them in the forest areas of Jhapa and Morang. Initially, water was supplied through an electric pump from a borehole with support from UNHCR; however, it was quickly realized that this is expensive and unsustainable with high costs for maintenance of diesel and electric equipment and due to the deteriorating water security in that area. With help from the local council and UNHCR a new sustainable, low-cost gravity-flow water system has been introduced and is shared by refugees and the local host community. This becomes a model for mainstreaming infrastructure for refugees into locals’ service systems resulting in increased service quality for both refugees and the host communities (Paudyal & Burt, Citation2017). Such innovation also indicates that the application of sustainable water management practices is essential to secure water systems for the long term. Similarly, a study looked at water security in the Arab peninsula (Hussein et al., Citation2020) and found that refugee influxes do not deteriorate the existing water security issue but rather opened a window of opportunity to further strengthen infrastructural development in that region. Such national efforts are providing a solution to address this overarching critical issue (). This further indicates the necessity to explore the alternatives-to-camps’ approach that emphases careful planning to ensure mainstreamed or shared access to different basic services for the refugees and host community, so that the WaSH system can provide sustainable services whether refugees stay or leave.

Box 3. Example of water scarcity and refugee impact.

Wider environmental and social implications

The review found that only 5% of the literature addressed environmental impacts from refugees and camps, particularly those relevant to water security and sustainability, despite the SPHERE standard and other guidelines including specific measures to minimize environmental impact during operations to reduce conflict potential over access to natural resources. However, the available literature further stresses that despite it being mandatory to conduct an assessment before project intervention, the data from such environmental impact assessments are not available (Price, Citation2017), which hampers knowledge-sharing and development of best practices. Further, the studies pointed out the lack of clear understanding and awareness of why and how environmental issues should be addressed during provision of emergency WaSH activities. The role of international donor investment and funding criteria need to be revised to consider environmental issues in the design of WaSH interventions in such contexts. Long-term and flexible-funding options (contingent on evidence of assessment of environmental consideration, inclusion of indigenous knowledge) have been proposed so that the humanitarian actors can rethink and reshape their prospects in environmental issues in the emergency WaSH context from the very beginning of the response (Johnson et al., Citation2020). The absence of environmental impact analyses implies little understanding of how environmental related assessments are influencing decision-making and follow-up actions ().

Other environmental issues are found to impact the overall sustainability and health of refugee communities. While the UNHCR (Citation2001) reported that the majority of displaced persons are situated in climate change hotspots, many camps are unmanaged in terms of resource utilization. Overcrowded camps put a lot of pressure on natural resources and overexploitation of resources can become critical. For example, a study in Tanzania specifically mentioned refugees’ 65% overexploitation of natural resources compared with the host community (Whitaker, Citation2002), as the interventions provided for refugees or IDPs did not fulfil their needs, leading to overexploitation of the natural resources (Development Initiatives, Citation2017). Sometimes host communities use management loopholes to intensify deforestation as a response to increased needs. When the camps are operated for decades (e.g., Dadaab in Kenya, Karamojo in Uganda, and Darfur) the resource competition occurs more intensely. In addition, groundwater and soil contamination due to mismanagement of human faeces, inadequate drainage and overflow of sewage are often associated with camps. Further, the authors explained these issues with an F-diagram, whereby faeces led to water and food contamination. However, open defaecation is not the only reason, as household poultry and animal infestation (e.g., rabbits, rats) also contribute to pollution of the home environment. The number of diseases (i.e., cholera, diarrhoea, typhoid, hepatitis A and E as causes of liver inflammation and jaundice) with a faecal–oral transmission route highlight how difficult it is to achieve satisfactory WaSH conditions in camps. The few studies that have been conducted in refugee camps showed that challenges exist at different levels. For example, access to water and soap alone does not guarantee actual handwashing behaviour. The level of knowledge about the practice as well as alternative preferred utilization of soap (laundry) plays a role in achieving the desired behaviour in practice (Biran et al., Citation2012; Phillips et al., Citation2015).

In addition to environmental impacts, there are critical social issues responsible for disparities between refugee and local communities, such as limited rights and access to health and utility services, language barriers, literacy rate, and marital status (Adler et al., Citation2016; Feinberg et al., Citation2021). This has also been evidenced in high- and middle-income countries (Araya et al., Citation2019; Feinberg et al., Citation2021). The authors linked social determinants with the health impact and found severe structural inequalities, higher rates of unemployment, earning below minimum wages, language barriers and lack of knowledge regarding access to resources among refugees who are eventually granted rights to remain in countries such as the United States and Germany. A recent study among Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh found that ‘knowledge of WaSH, age, education, and marital status were associated with level of engagement in WaSH practices’ (Hsan et al., Citation2019, p. 799). Education, especially among mothers, has been identified as key to overall family hygiene success (McGarvey et al., Citation2008; Mekonnen & Ekubagewargies, Citation2019; Sintondji et al., Citation2017). An educated household appeared to be aware of environmental pollution and changed their lifestyle accordingly, using clean water and clean fuel. Involving communities in managing their facilities and practices and providing hygiene education at school are critical. Strengthening health education, and accounting for traditional beliefs and myths is critical to bridging gaps between knowledge and practice.

Institutional inclusiveness and participatory governance

There is also a lack of understanding of how the institutional arrangements and governance approach (6% of literature approached the role of governance) affects refugee communities. A few studies identified through this review emphasized the need for inclusiveness and participatory approaches at multiple scales of engagement. The studies emphasized the need to involve the refugee community in decision-making and intervention management. In this context, multi-scale engagement, referring to the project implementation with the association of international, national, regional and local actors’ involvement, is essential. Although the major humanitarian actors involved are largely within the UNHCR’s domination, there is increasing focus on the involvement of local hosting organizations that might further support refugee integration. Involving refugees in WaSH and health service delivery is important for several reasons. First, the involved refugees can share their life experiences and background which will be similar to that of others in the refugee community earning their trust. Second, workers from refugee backgrounds can relate to the situation and provide a solution suitable for that context. Finally, the worker can be culturally sensitive to the refugee community and have greater acceptance (O’Brien & Gostin, Citation2011; Pincock et al., Citation2020).

A study in Kenya and Uganda termed such involvement as refugee-led organizations (RLOs) in camps and found this to be a critical part of the success of Covid-19 pandemic responses. The authors identified five key areas where RLOs could be beneficial: (1) providing public information, (2) supplementing capacity gaps, (3) healthcare delivery, (4) shaping social norms and (5) virus tracking and contact tracing (Betts et al., Citation2021). The authors further stressed that their research had found:

how RLOs have pivoted their existing service provision to fill assistance gaps, including in areas directly related to public health. As the humanitarian system searches for ways to implement remote and participatory approaches to refugee assistance, RLOs offer great potential, if mechanisms can be found to identify those that are effective, provide them with funding, and build their capacities.(p. 3)

Involvement of refugees in interventions was also captured in other literature highlighting the importance of management and community liaisons working together on disaster preparedness and response opportunities (Marlowe, Citation2013).

A study in Germany by Araya et al. (Citation2019) also emphasizes involving the hosting community as actors in refugee integration and planning, with many other studies supporting this assertion, highlighting that:

A first step towards considering hosting communities as a valid stakeholder is to capture and benchmark hosting community perceptions of how services are rendered to displaced communities. Next, these views should be incorporated into the decision-making process of tailoring alternatives and policies of providing infrastructure services to displaced persons.(p. 30)

The authors indicated that this integration of host communities and co-management (i.e., deciding how to best accommodate displaced persons and provide them with water and wastewater services) promotes sustainable planning and the development of urban infrastructure and utility services. This is also true in the emerging economic countries context, which may have less complex infrastructure systems and a more reflexive and flexible approach to water services governance (Yasmin et al., Citation2022). We note, of course, that this is not a simple fix but requires complex negotiations and balancing of needs and resources, but co-development of solutions has been linked to a greater sense of co-ownership of both the challenge and the solution, and thus to reducing ‘us versus them’ considerations (Lachapelle, Citation2008).

The institutional domain has been critical to the failure or success of WaSH interventions, as conflicts between developmental interventions (long-term, systematic issues and solutions promoting economic, political, social or environmental development) and humanitarian interventions (short-term, during emergencies to relieve suffering) are not uncommon. There are also conflicts regarding sharing resources and responsibilities between disaster management, public health, and other national and regional-level institutions. In such contexts, a common problem with refugee and WaSH issues is that they fall between departments or span a number of departments’ remits. For example, in the Rohingya refugee camp, Bangladesh as the host country showed great collective effort by national organizations, HDOs (at both international and grassroots levels) in quickly setting up temporary shelters (Kutupalong, Nayapara and Vashan-Char camps) and other basic facilities, such as WaSH in Cox’s Bazar (Bangladesh). However, this was insufficient to ensure the resilience or sustainability of the WaSH intervention in this community due to the scale of the challenges for more than 1 million Rohingya refugees in terms of ensuring WaSH facilities in a place already struggling with overcrowding, lack of necessary basic services, and limitations of funding and planning (Akhter et al., Citation2020; Khan et al., Citation2020).

Wash resilience and sustainability

Contemporary research looked at different WaSH interventions and found limited exploration related to the different blocks presented in ), which can be categorized as interdependent factors in the broader environmental, social and technological domains that are necessary for developing capacity for refugee well-being, social and environmental integration, and can benefit from inclusiveness and multi-scale strategies to adapt and learn. Although there is evidence of successful WaSH system development following UNHCR or SPHERE standards (i.e., 35 litres per person per day of water; and 50 persons per communal toilet), the resilience and sustainability of WaSH do not depend on how strongly it is aligned with the guideline. On the contrary, the resilience and sustainability of WaSH depends on what end-value this system can provide for the future benefit of both refugee and host communities irrespective of whether refugees stay or leave that community (Paudyal & Burt, Citation2017; Tafere, Citation2018). For example, Van der Helm et al. (Citation2017) described an inter-agency humanitarian effort to design WaSH infrastructure in Zaatari camp, Jordan, that shifted from humanitarian towards more sustainable options. The investment conducted, through careful consideration of quality control of all processes and outputs, asset management and administrative strategies, should ensure that the infrastructure provided will have a life expectancy of at least 15–20 years (US EPA, Citation2014) if designed to minimum standards. Therefore, regardless of whether or not refugees remain, the infrastructure investment delivers future benefits to local communities. There have been numerous calls to HDOs and international actors that influence policy to highlight the suffering and difficulties of individuals and communities surviving protracted duration as refugees, as they are often forgotten, and the need for greater awareness for both the HDO staff and refugees of the impact of resource gaps on refugee suffering and host community impacts related to poor water, sanitation, health and nutrition services (Cronin et al., Citation2008).

WaSH resilience is largely framed by scholars and policy practitioners as ensuring service access rather than addressing the system itself. The SPHERE handbook (SPHERE Standards, Citation2018) states that agencies should ‘coordinate with WaSH, health, public works and other authorities, the private sector and other stakeholders to establish or re-establish sustainable waste management practices’ (p. 270). While some authors have framed WaSH infrastructure and design specification of the facilities (e.g., to ensure equitable access to safe water, adequate and appropriate sanitation facilities, and good hygiene education) as critical in ensuring resilience and sustaining services, others pointed towards planning and integration with the host infrastructure and master planning of the local areas as key factors for ensuring environmental sustainability. Others have suggested that the health system and WaSH systems of refugees and host communities should be interlinked and connected to reduce the risks of infectious disease outbreaks such as Covid-19 () (Akhter et al., Citation2020; Kassem & Jaafar, Citation2020).

Box 5. WaSH and the Covid-19 pandemic.

This review found that ensuring ‘sustainable and resilient’ WaSH in refugee camps is a very complex challenge and includes uncertainties across various interrelated factors including ecological, institutional and management, cultural and political, technological innovation and knowledge management, and their effectiveness to ensure positive behaviour change. These factors are interdependent and influence each other in terms of developing capacity for ensuring refugee well-being, social and environmental integration. Inclusive governance approaches with multi-scale strategies are needed to develop capacity for adaptation and capability to cope with change. further proposes a blueprint for a system approach to enable crisis responders develop beyond-camp approaches and longer-term sustainable WaSH solutions. The blueprint unpacks the factors (ecological, institutional and management, cultural and political, technological innovation and knowledge management) and their service-delivery functions in support of adaptation and learning for refugee and host community integration in the long term. This indicates that defining WaSH sustainability is a first critical step, which this paper attempts to do, and that an agreed and implementable definition of WaSH sustainability depends on understanding the roles and interdependences among these factors in each specific refugee camp context. Our definition recognizes that a ‘one size fits all’ solution to enhance the sustainability of one camp might not be suitable for other refugee camps.

The emerging concern around environmental and ecological factors and their function for WaSH centres on the debate around long-term sustainability of camps for both refugees and their host community. The location of camps in disaster-prone or climate hotspot areas, itself increasing their vulnerability, is coupled with stress arising from overcrowding that increases pressure on WaSH infrastructure and services access, leading to overexploitation of resources which increases water insecurity (reserves of ground or surface water, up- and downstream flow of river) and pollution (i.e., wastewater discharge into rivers or soil). As camps are developed during the emergency stage as a first response, there is very little pre-planning involved, and no thought is given to the camps’ long-term status. Despite environmental impact assessments being mandatory before camp planning, little evidence is found of this and environmental data are not available, which hampers knowledge sharing and development of best practices.

This absence of planning (which arises in part due to the rapid development of refugee crises and optimism that the situation is temporary despite grown evidence to the contrary) impacts overall sustainability and resilience, including WaSH (Akhter et al., Citation2020; Howard et al., Citation2020; Paudyal & Burt, Citation2017). For example, longer term planning should incorporate seasonal variation of the host country and the nature of its available water resources. Addressing dry season water security issues, for example, requires the incorporation of alternatives or innovative solutions along with conventional systems (i.e., rainwater-harvesting supplemented with the tap-stands or piped water supply). Such seasonal planning might help reduce flooding in the rainy seasons through the provision of drainage solutions or the selection of the camp location. Similarly, for wastewater management, pit-latrines are always on the verge of overflow from their drainage, and thus contaminate water and camp surroundings, therefore alternative solutions, such as urine diversion dehydration toilets or drainage systems should be developed to address overflow. Planning and designing of contamination monitoring points to needs to incorporate the end-user, as most of the literature has found that contamination largely occurs at the point of use rather than at the source.

The institutional and management approach is the core of sustainability planning for camps and several approaches, such as cluster and refugee led, with demand-driven, long-term, output and integration-focused initiatives identified herein as critical for WaSH sustainability. For example, understanding the duration and lifespan of relevant infrastructural and technological development in camps has been difficult due to the debate around average camp life, whereby the UNHCR is still reporting 10 years as the average camp life while in practice it has risen to 24 years. This has an impact on the ageing of infrastructure and services, built based on ‘10 years of average camp’, resulting in declining service delivery and persistent crises to maintain the standard and quantity of services (i.e., water supply and latrine) with ageing infrastructure. The literature suggests the development of WaSH infrastructure that can provide long-term services (Akhter et al., Citation2020; Howard et al., Citation2020; Paudyal & Burt, Citation2017). For instance, Bassi et al. (Citation2018) stated that the lifetime of any technology is correlated with the cost; if the lifespan of any technology increases more than the existing three to five years, its unit cost will be reduced by 21–38% depending on the system design. The authors recommended that decision-makers explore case-specific life-cycle costing to understand sustainability, such as collecting water consumption data and consumption behaviour across seasons to capture the trade-offs between different options. Here, knowledge-sharing will be critical as emergency response needs are not compatible with extensive baseline analyses.

Involving host and refugee communities in decision-making (i.e., setting up shelters, latrines and bathing facilities, providing food and drinking water) is key to understanding the cultural and social differences that will support WaSH sustainability. For instance, the standard that pertains to design and building infrastructure and management systems for camps is different from those of the host community, which becomes a problem for integration with the local community services. Thus, reforms in international policies and discourses need to be translated into the national, regional and local context of the host community so that it can reform the local service-delivery mechanism and implement the necessary infrastructural development to meet the additional pressures created by the presence of refugees. Political influence is critical to all aspects of camp life. Political conflict and power struggle in the community impact who receives what support and who has a voice in project interventions. Sometimes host and refugee communities struggle with power dynamics and resulting conflicts hamper basic service delivery. Providing refugee communities and their representatives with the necessary education and incentives to practise hygiene and water storage management is key to maintaining hygiene.

Tafere (Citation2018) stressed that ‘A genuine care for the environment calls for a systems approach where environmental impacts of humanitarian and development aid are considered an integral part of the humanitarian response, DRR, achievement of SDGs, and in managing the climate nexus’ (p. 199). For example, if water resources are managed well, this will ensure adequate supply of water and better management of wastewater, thus ensuring better latrine management and improved hygiene practices (with adequate supply of water for washing and bathing) and preventing outbreak of diseases and public health crisis. Coupling the development of settlements to the introduction of innovations in environmental sustainability (e.g., use of low-cost solar desalination/water purification on-site) and potentially job-creation opportunities for refugees will provide an important new avenue to escape the current situation of indefinite duration camps.

Conclusions

A systematic review of peer-reviewed and organizational literature was conducted to understand coherence across WaSH interventions, public health risks and DRR strategies in refugee settlements, especially camps. Our objectives were to unpack critical factors and outcomes for assessing the vulnerability and capacity context to understand the barriers and opportunities to explore sustainable and resilient WaSH systems in camps. After a two-phase screening of literature, 77 peer-reviewed journal articles and 34 organizational literatures met our three inclusion criteria for full-text review. The analysis indicates that contemporary research pays increasing attention to issues applicable across WaSH, public health hazards and disaster risk management following updates to adopted global directives and guidance at different scales of implementation, to ensure basic rights, well-being, and the dignity of refugees and IDPs. In terms of driving system-wide change towards a sustainable future, SPHERE standards do not necessarily equip stakeholders to deliver resilience in the long-run and should be updated (). The review identified barriers to sustainability including: the fact that environmental health is not widely considered; the absence of system-wide sustainability in access and services quality in camps’ pre-panning; and lack of consideration of other interrelated factors (i.e., ecological, institutional, cultural and knowledge management) to understand their influence and or nexus behaviour. With the waiting period for refugee repatriation or integration into host communities now being 24 years on average, and their accommodation being largely in low- and middle-income countries, the sustainability and resilience of WaSH becomes increasingly complex, and highly dependent on the societal and economic disparities already in place. Indeed, balancing the needs for immediate response, cost-efficiency and capacity to expand as refugee numbers grow requires a more holistic and long-term approach, integrating both host and refugee communities in co-developing the solutions. Therefore, building WaSH resilience and sustainability in such complex situations requires the consideration of various interdependent factors, that is, ecological, institutional, cultural factors, individually and collectively, and knowledge management. This requires adopting inclusive and multi-scale strategies, careful planning to ensure shared access to provide benefit to both refugees and host communities to support change. Indeed, the debate around camps or alternatives to camps is crucial in understanding the sustainability and resilience of WaSH systems. Camps might not be a sustainable solution for this number of people; however, a systems approach towards WaSH can be a milestone to achieving the alternative-to-camps solutions which integrate sustainability and environmental considerations from the earliest (emergency response) stage to achieve WaSH resilience and sustainability.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (206.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2022.2131362

References

- Abubakar, I., Aldridge, R. W., Devakumar, D., Orcutt, M., Burns, R., Barreto, M. L., Dhavan, P., Fouad, F. M., Groce, N., Guo, Y., Hargreaves, S., Knipper, M., Miranda, J. J., Madise, N., Kumar, B., Mosca, D., McGovern, T., Rubenstein, L., Sammonds, P., … Zhou, S. (2018). The UCL–Lancet commission on migration and health: The health of a world on the move. The Lancet, 392(10164), 2606–2654. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7

- Adler, N. E., Glymour, M. M., & Fielding, J. (2016). Addressing social determinants of health and health inequalities. JAMA, 316(16), 1641. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.14058

- Ahmad, J., Ahmad, M. M., Sadia, H., & Ahmad, A. (2017). Using selected global health indicators to assess public health status of population displaced by natural and man-made disasters. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 22, 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.03.005

- Akhter, M., Uddin, S. M. N., Rafa, N., Hridi, S. M., Staddon, C., & Powell, W. (2020). Drinking water security challenges in Rohingya refugee camps of cox’s bazar, Bangladesh. Sustainability, 12(18), 7325. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187325

- Ali, S. I., Ali, S. S., & Fesselet, J. F. (2021). Evidence-based chlorination targets for household water safety in humanitarian settings: Recommendations from a multi-site study in refugee camps in South Sudan, Jordan, and Rwanda. Water Research, 189, 116642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2020.116642

- Araya, F., Faust, K. M., & Kaminsky, J. A. (2019). Public perceptions from hosting communities: The impact of displaced persons on critical infrastructure. Sustainable Cities and Society, 48, 101508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101508

- Atuyambe, L. M., Ediau, M., Orach, C. G., Musenero, M., & Bazeyo, W. (2011). Land slide disaster in eastern Uganda: Rapid assessment of water, sanitation and hygiene situation in Bulucheke camp, Bududa district. Environmental Health, 10(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-10-38

- Bassi, A., Tange, S., Holm, I., Boldrin, B. A., & Rygaard, M. (2018). A multi-criteria assessment of water supply in Ugandan refugee settlements. Water, 10(10), 1493. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10101493

- BBC News. (2021). https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-kent-58186216

- Betts, A., Easton-Calabria, E., & Pincock, K. (2021). Localising public health: Refugee-led organisations as first and last responders in COVID-19. World Development, 139, 105311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105311

- Bhattacharjee, M. (2019). Menstrual hygiene management during emergencies: A study of challenges faced by women and adolescent girls living in flood-prone districts in Assam. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 26(1–2), 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971521518811172

- Biran, A., Schmidt, W. P., Zeleke, L., Emukule, H., Khay, H., Parker, J., & Peprah, D. (2012). Hygiene and sanitation practices amongst residents of three long‐term refugee camps in Thailand, Ethiopia and Kenya. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 17(9), 1133–1141. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03045.x

- Bisi-Johnson, M. A., Adediran, K. O., Akinola, S. A., Popoola, E. O., & Okoh, A. I. (2017). Comparative physicochemical and microbiological qualities of source and stored household waters in some selected communities in southwestern Nigeria. Sustainability, 9(3), 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9030454

- Biswas, A. K., & Quiroz, C. T. (1996). Environmental impacts of refugees: A case study. Impact Assessment, 14(1), 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/07349165.1996.9725884

- Brown, O. (2008). Migration and climate change. IOM migration research series no. 31 (pp. 7). International Organization for Migration.

- Brauer, M., Zhao, J. T., Bennitt, F. B., & Stanaway, J. D. (2020). Global access to handwashing: Implications for COVID-19 control in low-income ountries. Environmental Health Perspectives, 128(5), 057005.

- Chan, E. Y., Chiu, C. P., & Chan, G. K. (2018). Medical and health risks associated with communicable diseases of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh 2017. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 68, 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2018.01.001

- Clasen, T. F., & Bastable, A. (2003). Faecal contamination of drinking water during collection and household storage: The need to extend protection to the point of use. Journal of Water and Health, 1(3), 109–115. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2003.0013

- Connolly, M. A., Gayer, M., Ryan, M. J., Salama, P., Spiegel, P., & Heymann, D. L. (2004). Communicable diseases in complex emergencies: Impact and challenges. The Lancet, 364(9449), 1974–1983. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17481-3

- Cooper, B., Behnke, N. L., Cronk, R., Anthonj, C., Shackelford, B. B., Tu, R., & Bartram, J. (2020). Environmental health conditions in the transitional stage of forcible displacement: A systematic scoping review. Science of the Total Environment, 762, 143136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143136

- Cronin, A. A., Shrestha, D., Cornier, N., Abdalla, F., Ezard, N., & Aramburu, C. (2008). A review of water and sanitation provision in refugee camps in association with selected health and nutrition indicators–the need for integrated service provision. Journal of Water and Health, 6(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2007.019

- Cronin, A. A., Shrestha, D., Spiegel, P., Gore, F., & Hering, H. (2009). Quantifying the burden of disease associated with inadequate provision of water and sanitation in selected sub-Saharan refugee camps. Journal of Water and Health, 7(4), 557–568. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2009.089

- Day, S. J., Forster, T., & Schweitzer, R. (2020). Water supply in protracted humanitarian crises: Reflections on the sustainability of service delivery models. https://doi.org/10.21201/2020.6362

- De Goyet, C. D. V., Marti, R. Z., & Osorio, C. (2006). Natural disaster mitigation and relief (2nd) ed.). Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries.

- Development Initiatives. (2017). Development Initiatives’ progress in 2017. http://devinit.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Development-Initiatives-Progress-Report-2017.pdf

- Dhesi, S., Isakjee, A., & Davies, T. (2015). An environmental health assessment of the new migrant camp in Calais. University of Birmingham.

- Dhesi, S., Isakjee, A., & Davies, T. (2018). Public health in the Calais refugee camp: Environment, health and exclusion. Critical Public Health, 28(2), 140–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2017.1335860

- Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34

- Eid, H. (2008). Introduction: Countering the Nakba. Nebula, 5(3), 1–8. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A186321550/AONE?u=anon~8afc639&sid=googleScholar&xid=9cbd80fe

- EU Drinking Water Directives revised in 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/water/water-drink/legislation_en.html

- Faust, K. M., Roy, A., Feinstein, S., Poleacovschi, C., & Kaminsky, J. (2021). Individual responsibility towards providing water and wastewater public goods for displaced persons: How much and how long is the public willing to pay? Sustainable Cities and Society, 68, 102785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.102785

- Feinberg, I., O’Connor, M. H., Owen-Smith, A., & Dube, S. R. (2021). Public health crisis in the refugee community: Little change in social determinants of health preserve health disparities. Health Education Research, 36(2), 170–177. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyab004

- Few, R. (2007). Health and climatic hazards: Framing social research on vulnerability, response and adaptation. Global Environmental Change, 17(2), 281–295.

- Finch, T. (2015). In limbo in world’s oldest refugee camps: Where 10 million people can spend years, or even decades. Index on Censorship, 44(1), 53–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306422015569438

- Gensch, R., & Tillett, W. (2019). Strengthening sanitation and hygiene in the WASH systems conceptual framework. Discussion Paper. Welthungerhilfe and Sustainable Services Initiative, https://washagendaforchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/ssi_sh-discussion-paper_final_191014.pdf

- The Guardian. (2021). https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/jul/11/napier-barracks-staff-asylum-seekers-die-covid-health

- Hamid, M. M. A., Eljack, I. A., Osman, M. K. M., Elaagip, A. H., & Muneer, M. S. (2015). The prevalence of Hymenolepis nana among preschool children of displacement communities in Khartoum state, Sudan: A cross-sectional study. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 13(2), 172–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2014.12.011

- Hannah, D. M., Lynch, I., Mao, F., Miller, J. D., Young, S. L., & Krause, S. (2020). Water and sanitation for all in a pandemic. Nature Sustainability, 3(10), 773–775. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0593-7

- Howard, G., Bartram, J., Brocklehurst, C., Colford, J. M., Costa, F., Cunliffe, D., Dreibelbis, R., Eisenberg, J. N. S., Evans, B., Girones, R., Hrudey, S., Willetts, J., & Wright, C. Y. (2020). COVID-19: Urgent actions, critical reflections and future relevance of ‘WaSH’: Lessons for the current and future pandemics. Journal of Water and Health, 18(5), 613–630. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2020.162

- Hsan, K., Naher, S., Griffiths, M. D., Shamol, H. H., & Rahman, M. A. (2019). Factors associated with the practice of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) among the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 9(4), 794–800. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2019.038

- Hussein, H., Natta, A., Yehya, A. A. K., & Hamadna, B. (2020). Syrian refugees, water scarcity, and dynamic policies: How do the new refugee discourses impact water governance debates in Lebanon and Jordan? Water, 12(2), 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12020325

- Huston, A., & Moriarty, P. (2018). Understanding the WASH system and its building blocks. https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/084-201813wp_buildingblocksdef_newweb.pdf

- Idris, I. (2017). Effectiveness of various refugee settlement approaches K4D Helpdesk Report 223. Institute of Development Studies

- IOM. (2019). https://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms

- IOM. (2019, April–November). Site management & site development daily incident report: survey analysis. The International Organization for Migration –Bangladesh Mission. https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/npm_smsd_daily_incident_report_2019_survey_analysis.pdf

- Jang, S., Ekyalongo, Y., & Kim, H. (2021). Systematic review of displacement and health impact from natural disasters in Southeast Asia. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 15(1), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2019.125

- Johnson, A., Mele, I., Merola, F., & Plewa, K. (2020). No Plan B: The importance of environmental considerations in humanitarian contexts. London School of Economics and Political Science. https://eecentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/LSE_No-Plan-B_The-Importance-of-Environmental-Considerations-in-Humanitarian-Contexts.pdf

- Kassem, I. I., & Jaafar, H. (2020). The potential impact of water quality on the spread and control of COVID-19 in Syrian refugee camps in Lebanon. Water International, 45(5), 423–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2020.1780042

- Khan, M. N., Islam, M. M., & Rahman, M. M. (2020). Risks of COVID19 outbreaks in Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh. Public Health in Practice, 1, 100018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhip.2020.100018

- Lachapelle, P. (2008). A sense of ownership in community development: Understanding the potential for participation in community planning efforts. Community Development, 39(2), 52–59.

- Leaning, J., Spiegel, P., & Crisp, J. (2011). Public health equity in refugee situations. Conflict and Health, 5(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-5-6

- Mahamud, A. S., Ahmed, J. A., Nyoka, R., Auko, E., Kahi, V., Ndirangu, J., Nguhi, M., Burton, J. W., Muhindo, B. Z., Breiman, R. F., & Eidex, R. B. (2012). Epidemic cholera in Kakuma Refugee Camp, Kenya, 2009: The importance of sanitation and soap. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries, 6(3), 234–241. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.1966

- Marlowe, J. (2013). Resettled refugee community perspectives to the Canterbury earthquakes: Implications for organizational response. Disaster Prevention and Management, (5), 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-01-2013-0019

- McGarvey, S. T., Buszin, J., Reed, H., Smith, D. C., Rahman, Z., Andrzejewski, C., Awusabo-Asare, K., & White, M. J. (2008). Community and household determinants of water quality in coastal Ghana. Journal of Water and Health, 6(3), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2008.057

- Mekonnen, H. S., & Ekubagewargies, D. T. (2019). Prevalence and factors associated with intestinal parasites among under-five children attending Woreta Health Center, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Infectious Diseases, 19(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3884-8

- Miliband, D., & Tessema, M. T. (2018). The unmet needs of refugees and internally displaced people. The Lancet, 392(10164), 2530–2532. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32780-6

- Mizutori, M. (2020). International guide to value and engage children and youth in disaster risk reduction. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 35(2), 5–6. https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/media/7662/ajem_02_2020-04.pdf

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Research methods & reporting. British Medical Journal, 339, 333. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c869

- Nelson, E. L., Saade, D. R., & Gregg Greenough, P. (2020). Gender-based vulnerability: Combining Pareto ranking and spatial statistics to model gender-based vulnerability in Rohingya refugee settlements in Bangladesh. International Journal of Health Geographics, 19(1), 1–14.2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12942-020-00215-3

- Nicole, W. (2015). The WASH approach: Fighting waterborne diseases in emergency situations. Environmental Health Perspectives, 123(1). https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.123-A6

- O’Brien, P., & Gostin, L. O. (2011). Health worker shortages and global justice. Health Worker Shortages and Global Justice, Millbank Memorial Fund. https://www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/healthworkershortages-1.pdf

- Paudyal, P., & Burt, M. (2017). Host and refugee population cooperation: Case of Dumse water supply and sanitation project, Damak-5. Conference contribution. https://hdl.handle.net/2134/31527.