ABSTRACT

This paper investigates individual’s perceptions of inequality and the impact this has on mass public opinion support for the European Union (EU) in the Republic of Ireland. This question is posed in the context of the onset of the economic and financial crisis of 2007/8 as the crisis can be regarded as a critical juncture in Ireland’s relationship with the EU as a result of the economic downturn and the widening of economic disparities individuals have experienced. Ireland is a critical case in examining EU support as since its accession to the EU in 1973 it is often considered an exemplar of what the EU could offer small member states with a strongly pro-integrationist mass public. Using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) multiple regression analysis on 2009 European Election Study (EES) data, this paper shows that individuals’ concerns about inequality lowers support for the EU as it is currently constituted, but increases support for continued European integration. This suggests that individual-levels of support may be in a precarious state, yet they can be salvaged as individuals in Ireland regard the EU as the institutional-driving force to address market-generated inequality.

1. Introduction

Recent trends suggest that the EU citizenry is becoming more critical of the EU (Anderson & Reichert, Citation1995; Brinegar & Jolly, Citation2005; de Vreese & Boomgaarden, Citation2005; Eichenberg & Dalton, Citation2007; Franklin, Van der Eijk, & Marsh, Citation1995; Kuhn & Stoeckel, Citation2014; Loveless, Citation2010; Norris, Citation1999; Rohrschneider & Loveless, Citation2010). Following the 2007/8 financial crisis, there is a greater percentage of individuals who may not be objectively ‘poor’ but feel themselves to be at a heightened risk of economic adversity as a result of rising inequality and economic problems in both their respective member state and the EU. These individuals are likely to be more supportive of income redistribution as a means to minimise their own economic insecurity. While these preferences for increased economic security may not be unexpected, what this would produce in terms of changes in support for the EU project is unclear.

Using the European Election Study (EES) 2009 survey dataset in Ireland and conducting an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) multiple regression analysis this paper shows the importance individuals place on addressing inequality is positively correlated with support for further European integration but not for the EU as it is currently constituted (i.e. status quo). This is important as it informs our understanding of popular support for the EU in Ireland. What is notable about these findings is that there is little evidence that this effect is a direct function of economic ‘winning and losing’ via individual’s socio-economic status (Gabel, Citation1998; Gabel & Palmer, Citation1995). Moreover, economic losing and its assumed negative effects on support for the EU may be more nuanced and widespread. Overall, individuals in Ireland are disappointed by the current performance of the EU and express concerns about economic conditions particularly those who experience increased economic instability and insecurity. However, these individuals also appear to be more supportive of the EU in the future.

I propose the following understanding for individual’s attitudes towards the EU in Ireland. While the EU has long been, an economic project coupled with a normative democratic framework, the evidence here suggests that support for the EU in Ireland moves with a desire for democratic politics to play a more stabilising role in the economy. Following the economic crisis of 2007/8, even if the EU is seen to have failed to create adequate economic and social opportunities or has provided these prospects in an unequal manner, EU membership may still represent assurance that both economic and political institutions can work effectively. In addition to traditionally identified groups of ‘losers’ these ‘new losers’ appear to be supportive of the EU as a means to buttress democratic power at both the national and supranational level based on the belief that democracy is the mechanism to combat market-generated inequalities. This suggests that the EU should reflect Irish individuals’ preferences for fairness and justice in society via strong and effective democratic institutions that function to diminish excessive market distortions.

2. Irish attitudes towards the EU

Ireland is often regarded as one of the most enthusiastic supporters of European integration since its accession to the EU in 1973 as they are often considered as ‘good Europeans’ with a pro-integrationist attitude (Adshead & Tonge, Citation2009; Gilland, Citation2002; Kennedy & Sinnott, Citation2006, Citation2007; Lyons, Citation2008; Sinnott, Citation1995, Citation2002, Citation2005). However, the reality of Irish public opinion is more nuanced: support for the EU in Ireland is not a single entity, but a complex set of opinions determined by a variety of factors. Research has shown that since the 1990’s knowledge about the EU amongst the Irish public is low (Garry, Marsh, & Sinnott, Citation2005; Holmes, Citation2005; Kennedy & Sinnott, Citation2006, Citation2007; Laffan & O’Mahony, Citation2008, p. 128) with individuals in Ireland more likely to refer to the economic aspects of the EU, such as the freedom of movement, the Euro and economic prosperity. This ‘knowledge deficit’ is perhaps not surprising as for the first twenty years of EU membership Ireland’s self-perception of its status within the EU was that of a small, poor, peripheral member state. In their examination of the nuances of Irish public opinion toward the EU Kennedy and Sinnott (Citation2007) find that Irish individuals’ knowledge of the EU does not affect the relationship between opinion of EU support and evaluations of domestic and European institutions. Therefore, the EU project in Ireland is not one which can be encapsulated by a single overarching judgment, but by many different facets.

Between 1972 and 2012, Irish governments have held nine European referendum campaigns. The emergence of referendums as key forums for debate about the EU in Ireland has resulted in a much greater degree of polarisation of opinions with Garry et al. (Citation2005) and Glencross and Trechsel (Citation2011) demonstrating that voting in EU-related referendums typically distinguish between ‘second-order’ effects and the impact of ‘substantive’ ‘issues’. As Garry (Citation2013) correctly points out, findings with regards to both ‘second-order’ and ‘issue-voting’ approaches are of significant theoretical importance for the understanding of individual-level political behaviour and normative evaluations of the practicality of using the mechanism of referendums to ratify EU treaties. While both approaches are important for the wider debate they are opaque and difficult approaches to adopt when examining individual-level mass public opinion attitudes towards the EU in Ireland. Overall, they deflect from a thorough examination of individual-level normative attitudes towards support for the EU in Ireland. From this, it is evident that the EU is an economic project combined with a democratic normative framework suggesting that support for the EU shifts with a desire for politics, in particular political institutions, to play a robust role in stabilising the economy and this addressing inequality since the onset of the economic crisis in 2007/8.

3. Inequality and support for European integration

The economic and financial crisis of 2007/8 can be regarded as a critical juncture in Ireland’s relationship with the EU, as a result of the economic downturn and a widening of economic disparities individuals have experienced. Individuals and labour market participants perceive the costs and benefits of European integration differently depending upon national wage bargaining systems of welfare state policies (Brinegar, Jolly, & Kitschelt, Citation2004). In particular, ‘domestic political divides between advocates and opponents of EU integration may play out differently and yield contrasting partisan alignments if polities are embedded in different institutional “varieties” of capitalism’ (Brinegar et al., Citation2004, p. 62).

Capitalist institutions affect the proportion of voters in each EU member state who have an incentive to challenge European integration. It is the political economy which shapes the ‘grievance level’ that may deliver the patterns of domestic contestation (Brinegar et al., Citation2004, p. 62) by focusing upon individuals’ socio-tropic evaluations of European integration as well as the cost and benefits that result from changes in the expected economic benefits created by European integration for national political and economic institutions. In addition, individuals’ focus on egocentric voting preferences for European integration is not based on whether individuals are ‘left’ or ‘right’ in ideological terms, but whether they are ‘left’ or ‘right’ within their national political-economic context. The ‘varieties of capitalism’ literature suggests that the economic crisis has affected liberal market economies more severely than coordinated market economies (Bernhagen & Chari, Citation2011; Chari & Bernhagen, Citation2011). Therefore, when analysing Ireland through the lens of ‘varieties of capitalism’ it is individuals’ preferences to be either ‘left’ or ‘right’ in terms of the national political-economic context and the contextualisation that liberal market economies have been affected more since the onset of the economic crisis which are important in determining individuals’ attitudes to address inequality and how they subsequently influence support for the EU.

The onset of the 2007/8 economic crisis and the Irish context highlights the heightened risk of economic adversity for individuals as a result of rising economic problems in both Ireland and the EU. These individuals are likely to be more supportive of income distribution as a means to minimise their own economic insecurity. The focus on European integration is now towards a more individualist egocentric perspective. The theoretical mechanism linking institutions and Irish individuals’ assessments of EU integration is the ‘perception of costs and benefits accruing from integration in light of domestic capitalist institutions’ (Brinegar et al., Citation2004, p. 64). When assessing the economic crisis, individuals consider its impact on their country’s economy. An EU member state’s status as a net beneficiary of European transfers (Anderson & Reichert, Citation1995; Carrubba, Citation2001; Eichenberg & Dalton, Citation1993) and intra-European trade (Anderson & Reichert, Citation1995) are important determinants of EU support. Indicators of macro-economic growth, inflation and unemployment influence aggregate EU support (Anderson & Kaltenhaler, Citation1996). Since Ireland is a net beneficiary of EU transfers it is plausible that individuals in Ireland base their opinion of the EU upon the implications for the national economy.

European integration now differs from European integration pre-economic crisis. While European integration has primarily focused upon market liberalisation, European economic governance now operates in a different direction by imposing regulation and increased (supranational) oversight on banks and markets (Kuhn & Stoeckel, Citation2014, p. 625). The beginning of the economic crisis of 2007/8 hinges upon this pre- and post- phase of European integration in Ireland and as a result it is expected to lead to a resurgence in Gabel’s (Gabel, Citation1998; Gabel & Palmer, Citation1995; Gabel & Whitten, Citation1997) ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ thesis. This resurgence derives from the onset of the economic and financial crisis of 2007/8 and continuing economic recession in Europe, which has created a new group of ‘losers’ in the EU project. This new group of ‘losers’ continues to be socio-economically secure but it includes those individuals who perceive themselves to be pushed closer to the economic edge of ‘losing’. Put simply, following the 2007/8 economic crisis there is a greater percentage of people in Ireland who may not be objectively ‘poor’, but who feel themselves to be at a heightened risk of economic adversity due to rising inequality and economic problems in Ireland and the EU. These individuals are likely to be more supportive of income redistribution as a means to minimise their own economic insecurity.

This is vital for the understanding of individuals’ changing support for the EU in Ireland. The extensive nature of individuals’ support for the EU in Ireland suggests that the EU should reflect EU citizens’ preferences for fairness and justice in society via strong and effective democratic institutions. These institutions will then act and function in order to diminish excessive market distortions. It appears that, following the economic crisis of 2007/8, if the EU is regarded by individuals to have failed to create adequate and social opportunities, or has provided these prospects in an unequal manner, membership of the EU may still represent assurance for individuals that both economic and political institutions can and will work effectively in order to address inequality.

In Ireland, the European integration project has for many years been motivated by economic objectives based upon utilitarian factors. The Irish tendency has followed a stance of ‘not what the country could do for Europe, but what Europe could do for the country’ (Holmes, Citation2005, p. 2). Ireland has adopted a highly practical approach to European integration and has acquired a reputation of being supportive of European integration while also acquiring one of a ‘begging bowl’ mentality operating in a reactive self-interest manner (Hussey, Citation1993; Matthews, Citation1983). As a result, the most extensively analysed economic variables influencing attitudes towards integration in Ireland are factors such as the level of unemployment, inflation and net receipts, or payments, from the EU (Anderson & Reichert, Citation1995 ; Gabel & Whitten, Citation1997; Garry et al., Citation2005; Kennedy & Sinnott, Citation2006; Laffan & O’Mahony, Citation2008; Loveless, Citation2010).

The boom years of the Celtic Tiger (1995–2007) saw increased levels of income inequality as the top section of the income distribution pulled away from the median and by 2007, the average levels of income inequality over the Celtic Tiger period remained stubbornly high (Dellepaine & Hardiman, Citation2012, p. 86). The rapid growth and employment expansion combined with an on-going commitment to Social PartnershipFootnote1 processes did not contribute to a reduction in domestic social inequalities or to an expansion in the extent of social consumption. The increase in public spending that took place did not keep pace with market-driven living standards and the tax system favoured, rather than contained, the surge in higher income rewards (Ibid, p. 87).

In order to bring this in to the understanding of citizens’ support for the EU, it is the connection between individuals’ concerns about inequality and the changes in individuals’ level of support for the EU through the relationship inequality has to both political institutions and the liberal market economy. I do not posit that individuals in Ireland want an alternative arrangement with political democracy and the free market economy of the EU, but rather that individuals in Ireland want democratic institutions and the liberal market economy to both function effectively (Rohrschneider & Whitefield, Citation2006). It is much more productive to consider the market and democracy as mutually enforcing mechanisms so that the liberal market economy can produce improved economic outcomes for a larger proportion of individuals in Ireland in conjunction with robust and efficient democratic institutions.

If an economy provides high living standards and dynamic economic development, individuals will accept objective levels of inequality (Bollen & Jackman, Citation1985). This makes the balance between market-generated inequalities and effective democratic institutions a plausible argument as states with strong democratic political institutions are regarded by individuals as the guarantor against excessive inequalities (Bollen & Jackman, Citation1985; Reuveny & Li, Citation2003; Szelenyi & Kostello, Citation1996; Whitefield & Loveless, Citation2013). When economies fail, democratic political institutions must work. Therefore, I propose that in the wake of the economic and financial crisis, the EU may be regarded as a potential guarantor of democracy that can, as one of its many functions, combat market-driven inequalities.

This analysis does not overturn Gabel’s (Gabel, Citation1998; Gabel & Palmer, Citation1995; Gabel & Whitten, Citation1997) work but in fact expands the definition of ‘loser’. I expect that traditional winners and losers of EU integration will continue to reflect long-standing preferences for the EU. However, in conjunction, I also expect that those concerned about economic conditions will reflect a cross-current of determinants of support for the EU project. Thus, theoretically, I suggest that those who have been moved towards greater economic insecurity (i.e. the new losers) see democracy as the key mechanism to combat market-generated inequalities. Therefore, rather than reflect the anti-EU of the sociodemographic ‘losing’ profile, the expectation is that that those individuals concerned about economic insecurity, the potential ‘new losers’ are more supportive of the EU as a means to reinforce democratic power at the national and supranational level. I hypothesise that as the level of individuals’ preferences for inequality to be addressed increases, individuals are more likely to support the EU and its continued integration. I also note that if concerns with inequality are driven by the desire to see the economic costs of inequality mitigated through democratic means, support for the EU will only benefit if the EU is perceived to have performed well. If the EU has not performed well, I expect to see a loss of support for current performance.

4. Methodology

Increased support for the EU and the continuation of the EU project suggest that individuals in Ireland regard the EU as the enforcer of democratic political institutions which appeal to justice, fairness and transparency. Decreased support for the EU is considered in conjunction with increased concerns by individuals in Ireland of the ability of the EU to address inequality. This is suggestive of the on-going battle with the perceived democratic deficit of the EU, concerns of the efficacy of the EU and a preference for the Irish government to be the basis of effective action against inequality. In any of these latter cases, Irish individuals’ concerns with inequality depress support for the EU. The theory that combines Irish individuals’ concern about addressing inequality with support for the EU and Irish national governance rests on the notion that citizens in Ireland seek strong democratic politics to serve as a safeguard against market-generated inequalities (Reuveny & Li, Citation2003; Szelenyi & Kostello, Citation1996; Whitefield & Loveless, Citation2013). This leads to the hypothesis that;

Hypothesis 1: In Ireland, as the level of individuals’ preferences for inequality to be addressed increases, Irish individuals are more likely to support the EU (EU Status quo) and continued expansion (EU Enlargement).

To operationalise this hypothesis, I use the EES 2009 dataFootnote2 to examine support for the EU (see Appendix for all data and variables). Boomgaarden, Schuck, Elenbaas, and de Vreese (Citation2011) argue that attitudes towards the EU are multidimensional, making it relevant to assess which generic models explain variation in support or aversion to the different dimensions of EU support. Boomgaarden et al. (Citation2011) argue that measures of EU attitudes refer to two clusters of EU attitude orientations. The first cluster relates to specific, utilitarian and output oriented attitudes, while the second relates to diffuse, affective and input oriented attitudes.

In this paper, I also distinguish between attitudes towards the regime and towards the community by separating EU support into two categories: the EU status quo and EU enlargement. This builds upon the findings of Boomgaarden et al. (Citation2011) that emotional responses (i.e. perceptions), along with the performance of the functioning of the EU, both democratically and economically strengthens utilitarian attitudes towards the EU and reflects support based on agreement with extended decision-making competencies, policy transfer and further European integration. Therefore, in order to test the robustness of the approach I include three of them here:

EU membership is good or bad

EU enlargement is good or bad

EU is in our interest

Using OLS Multiple Regression analysis,Footnote3 I run three models of EU support in order to test the theoretical mechanism that individuals in Ireland seek strong democratic politics to serve as a safeguard against market-generated inequalities since the onset of the economic and financial crisis of 2007/8. This necessitates the inclusion of ‘addressing inequality’ into the mass public opinion model thus examining the performance of all three models in Ireland immediately after the onset of the economic and financial crisis of 2007/8.

5. Results

shows the co-variation of the three dependent variables. Each dependent variable varies from one another yet none of the three variables are substantively correlated with one another. This suggests the importance of operationalisation due to the conceptual distinctiveness between the EU as it is currently constituted (i.e. EU Status Quo), and the continued expansion of the EU project (i.e. EU Enlargement).

Table 1. Co-variation of EU support variables.

There are numerous approaches to the understanding of EU support (Loveless & Rohrschneider, Citation2008). The standard model of EU support includes communication (social communication, watching mass media and interest in politics), identity (feeling about being described as European, and fear of immigrants), ideological congruence and institutional performance (including retrospective and prospective socio-tropic economic evaluations as well as normative preferences for the liberal market economy and satisfaction with democracy), and socio-demographic variables (including self-reported social class, subjective standard of living, age, gender, ideology, and education).

For the central independent variable concerning inequality, I ask this question in the context of the onset of the economic crisis therefore constructing the conceptual basis for inequality in the fundamental premise that inequality is generated by market economies and democratic institutions are expected to balance the power of economic elite widely dispersed political power (Bartels, Citation2008; Kaltenhaler, Ceccoli, & Gellneny, Citation2008).Footnote4 Thus, I base my understanding on existing underlying normative attitudes that the market should be fair (vs. purely equal) and democracy should function in a roughly egalitarian, or minimally majoritarian, manner to combat excessive and inevitable market distortions (Whitefield & Loveless, Citation2013) in Ireland.

To operationalise this rationale, individual respondents in Ireland were asked how they deem the importance of addressing inequality to be using the question ‘income and wealth should be redistributed towards ordinary people’.Footnote5 I take this to be a value position that demonstrates individual respondents’ support for democratic institutions to serve as the arbiter of liberal market generated inequality. In order to show that this measure of inequality is not a proxy for other value positions and can be independently predictive of support for the EU, I analyse how the variable of inequality correlates with both ideological and socio-economic positions. The hypothesis, meanwhile, relies on the assumption that individuals in Ireland, regard the EU as a mechanism to reinforce substantive democratic governance at both the national level (i.e. Ireland) and at the supranational level (i.e. the EU). The analysis demonstrates that an increased number of individuals in Ireland concerned about inequality lowers support for the EU as it is currently constituted (i.e. status quo) but increases support for deeper European integration. This wide-ranging effect is for the most part unrelated to individuals’ socio-economic status of ‘winning’ and ‘losing’ but is driven by normative values of fairness and justice in society, suggesting that individuals in Ireland believe that is the institutional driving force to address market generated inequality in Ireland ().

Table 2. OLS multiple regression analysis: support for the EU in Ireland.

Across all three models of EU support the theoretically relevant variables of inequality, ideological congruence and institutional performance perform well. The central independent variable of ‘address inequality’ is positively correlated with both ‘EU enlargement’ and ‘EU in Ireland’s interests’. This infers that individuals believe that further enlargement of the EU, and the fact that decisions made in the EU are in the interest of Ireland, are factors which increase the need to address market generated inequality and as a consequence this increases mass public opinion support for the EU. However, in the model ‘EU membership is good or bad’ the central independent variable of ‘address inequality’ is negatively correlated and is not statistically significant. This suggests that inequality, or rather individuals’ belief that inequality should be addressed, has no effect on whether Ireland’s membership of the EU is either a good or bad thing.

Nonetheless, given the concern of individuals in Ireland about the issue of inequality and its apparent and differential effect on support for the EU since the onset of the economic and financial crisis of 2007/8 it is evident that inequality is a meaningful political, rather than merely economic, issue and one that needs substantive consideration. For individuals in Ireland, evaluations of support for the EU are not only economic but socio-tropic with many Irish people believing that the liberal market system functions in an unfair and unjust manner as they assess societal differences based upon both access and opportunity to the EU. This is reiterated theoretically by the ideological and institutional performance variables as they are almost uniformly positive and as expected.

In testing the theoretical mechanism, prospective socioeconomic evaluation and satisfaction with democracy are the best performing ideological congruence and institutional performance variables. Prospective socioeconomic evaluation is positively correlated with ‘EU membership’ and satisfaction with democracy positively correlated across all three models as well as being statistically significant across all three models. This further demonstrates that Irish individuals’ evaluations of support for the EU are not only economic but socio-tropic with many individuals in Ireland believing that the liberal market system functions in an unfair and unjust manner as they assess societal differences based upon both access and opportunity to the EU. This is a noteworthy finding given the intense criticism successive Irish governments have encountered since the economic crisis of 2007/8, with scholars citing a lack of expertise and inadequate governance as contributors to Irish socio-economic inequalities (Dellepaine & Hardiman, Citation2012; Kirby & Murphy, Citation2011).

Overall, the ‘identity’ variables are perhaps the most consistent predictor of support for the EU in Ireland as ‘European identity’ is positively correlated across all three models. The statistical significance and correlation coefficients across all three dependent variables for ‘European identity’ and across two models (EU membership and EU Enlargement) for ‘cultural fear’ emphasises the paradox that despite the fact that individuals in Ireland are widely regarded as ‘good Europeans with a pro-integrationist attitude’ there remains a nationalistic sentiment in Ireland. This is concurrent with the notion of perceived cultural threats (McLaren, Citation2002, Citation2004) and the inherent and implied ethnic level of Irish identity (Gilland, Citation2002).

For the socio-demographic variables, I note that similar to findings on support for the EU in the twenty-seven member states the reliance on Gabel’s (Gabel, Citation1998; Gabel & Palmer, Citation1995) ‘winners and losers’ thesis on static demographic variables may be deteriorating. The richer, younger, more educated males in Ireland no longer appear to regard the EU and further European integration as a net positive. Despite tending in a positive direction, as expected, education, age, self-reported social class, and subjective standard of living in Ireland are not statistically significant across all three models and are thus not powerful predictors in gauging EU support in Ireland.

Ideology provides limited consistency, as those individuals in Ireland who subscribe to the left of the political spectrum are less likely to support for the EU. Yet, those individuals who identify with the farthest right position are supportive of the EU, believing that the EU acts in Ireland’s interest. These are the most-opaque findings and at first glance may appear counterintuitive. However, one may posit that the negative support for the EU from individuals on the left, and positive support for the EU from those on the right, is indicative of a clear market position – note the strong positive effects of individuals’ prospective socioeconomic evaluation and membership of the EU. Therefore, it may be considered that both individuals on the left and the right support the EU such that those on the left would prefer to see more democracy and those on the right would rather a continuation of the EU’s apparent market profile. Overall this is an illustration of individuals’ normative view of inequality and that those individuals on the right support an increase in EU involvement in Irish economic governance as the EU is operating and functioning in the interest of Ireland by improving the liberal market position of Ireland, and therefore Irish individuals’ position in the market during the economic crisis. Put simply, individuals acknowledge that the EU is acting as the institutional driving force to address market-generated inequality in Ireland.

This conclusion is not unwarranted given the individual-level findings for the inequality variable. As individuals in Ireland agree with the notion that income and wealth should be redistributed towards ordinary people, support for the EU increases. This is consistent with the theoretical expectation. Individuals’ attitudes towards addressing inequality increases support for the EU, therefore lending support to the theoretical notion that EU citizens regard the EU as a means to reinforce substantive democratic governance at both the nation state level in Ireland and within the EU itself, namely as a means to combat excessive inequality.

6. Discussion

The economic and financial crisis had a profound immediate effect on the economic welfare of EU citizens (Eurofound Report, Citation2012). If the EU is regarded as primarily a market promoter via integration of national economies, it is reasonable to expect that those that are pushed, or perhaps those who perceive themselves and others to be pushed, towards a more fragile personal economic condition may be all the more critical of the EU and ongoing European integration. Kriesi et al. (Citation2008) argue that competition which is guided by changes in the economy, cultural diversity, competition between national governments and perceived encroachment of supranational politics have driven European societies in the theorised directions of Gabel’s (Citation1998; Gabel & Palmer, Citation1995) initial contribution over the past decades of EU expansion. However, ‘losers’ are not only ‘losers’ in continued European integration but also in the reduction of member states’ public sector capacity and a political willingness to continue the welfare state. The findings here demonstrate this highly plausible understanding in three ways.

Firstly, Irish attitudes towards addressing inequality increases support for the EU, in particular for further European integration. This is an interesting and noteworthy finding and points to the perception that individuals in Ireland believe that the Irish political system has failed the Irish people in reducing and addressing inequality. The intervention by the Irish government in the form of the Bank Guarantee Scheme of 2008 did not create greater certainty or stability in economic markets, as initially hoped, and individuals in Ireland were not protected from the uncertainty and risk of the liberal market economy. Irish individuals have recognised this uncertainty and risk of the liberal market economy and have demonstrated a preference for ‘more’ Europe, not ‘less’ Europe.

In order to link democratic institutions and Irish individuals’ perception of the unfair and unjust distribution of access and opportunity within the liberal market economy since the economic crisis to the understanding of individual-level support for the EU in Ireland, I draw a connection between Irish individuals’ concerns about inequality and changes in individual level support for the EU in Ireland. The findings here highlight that Irish individuals’ who want inequality to be addresses appear to be receptive to further European integration, while at the same time being dissatisfied with the EU’s current performance suggesting that the perceived ‘democratic deficit’ in the EU does continue to reinforce previous concerns about European governance (Rohrschneider, Citation2002).

However, popular dissatisfaction with the functioning of democracy tends to produce a desire for more, rather than less, democracy (Dalton, Citation2005; Norris, Citation1999). The findings here demonstrate that support for European integration via Irish individual’s concerns about addressing inequality suggests a prospective connection between the robust democratic enforcement that the EU could potentially offer. While not directly tested here, this suggests that the EU’s response to the crisis has been disproved by individuals in Ireland but despite this the EU has a positive role to play in addressing inequality. Whether the role to be played by the EU in addressing inequality supersedes the Irish nation state, or whether the EU’s role is one that reinforces the EU project, is opaque, ambiguous and difficult to discern. It may be conceived that the EU is being called upon in order to address inequality in a substantive manner, in addition to the action or inaction of the Irish state.

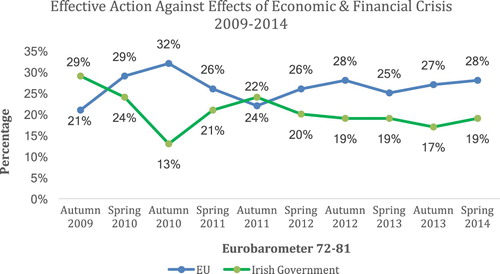

It is difficult to assess whether it is either the EU or the Irish state that is perceived by individuals in Ireland as being primarily responsible for the stabilisation of financial and economic markets and domestic and international economics following the economic crisis. However, recent Eurobarometer data (Eurobarometer 72, Autumn 2009 to Eurobarometer 80, Spring 2014) asks respondents: ‘In your opinion, which of the following is best able to take effective actions against the effects of the financial and economic crisis?’ ()Footnote6

Figure 1. Eurobarometer responses for ‘effective action against the effects of the financial & economic crisis’.

The individual-level responses are notable as individuals in Ireland regard the Irish state as much less effective in its action to manage the effects of the economic crisis since Spring 2010. It may be posited that for individuals in Ireland the question of effective action against the economic crisis may not have a clear answer. However, what is clear is that individuals in Ireland want more, not less EU democratic action. This demonstrates that the EU is indeed regarded by individuals in Ireland as the institutional driving force to address perceptions of inequality since the onset of the economic crisis. Here, inequality in the distribution of economic growth and or changes plays a strong role alongside Irish individuals’ actual socioeconomic status and social location acting as a determinant of Irish individuals’ support for on-going European integration, as well as an evaluative filter through which to assess the EU in its current form. When the liberal market distorts the distribution of goods in society, institutional remedies need to be available. If effective institutions are in fact the presumed remedy for inequality, analysis of changes in the level of support for the EU is possible, as well as a re-examination of the longstanding question of whether the EU may be valued more for its democratic character than its market character is possible which is directly demonstrated by the Eurobarometer data.

Secondly, it is not simply those individuals who find themselves in a more precarious economic position whose concern about inequality affects their support for the EU project as evaluations are not only economic but also sociotropic (Rohrschneider & Loveless, Citation2010). Put simply, the system can be regarded as too unfair thus making inequality representative of this as individuals assess societal differences in access and opportunity to the EU. It is possible that an individual could support the notion that income and wealth should be redistributed and at the same time be satisfied with the level of inequality. However, this is highly likely to be a small proportion of the population compared to those who are worried about inequality and support redistribution as concerns about inequality are strongly related to support for redistribution (Corneo & Gruner, Citation2002; Finseraas, Citation2012; Kenworthy & McCall, Citation2007; Rehm, Citation2009). The question throughout this analysis focuses on a normative preference for the EU project as opposed to a preference for a specific policy outcome. Therefore, the economic and financial crisis of 2007/8 has affected support for the EU and further European integration. The findings here demonstrate show that there is a widespread concern about inequality and the role of the EU (lower support for the EU as it is) as well as optimism for the EU project (support for further European integration) following the economic and financial crisis (Simpson & Loveless, Citation2017).

Thirdly and finally, the findings here in relation to the need to address inequality demonstrate a better understanding of individual level support for the EU. By linking higher levels of concern for addressing inequality with lower support for the EU as it is and higher levels of concern for addressing inequality with further European integration it may be posited that democracy and or democratic norms are only one set of potential mechanisms why individuals in Ireland display positive support for the EU as this as is not directly tested in the modelling strategy. What the findings do indicate is that the underpinning values of fairness and justice via strong and effective democratic institutions and processes may drive perceptions of inequality in Irish society with EU membership being much more than mere economic integration in the minds of Irish individuals.

7. Conclusion

Overall the findings here suggest that individuals’ attitudes and orientations towards the EU in Ireland are undergoing a predominant shift. The findings illustrate that individuals’ desire to address inequality is strongly correlated with negative support for the EU as it is, but positively correlated toward a deepening of EU integration. This finding depends on both individuals’ socio-economic location, making it a common explanation of support for the EU, as well as normatively supportive of stronger democratic institutional performance. This in turn allows an analysis of the changing nature and role of the EU in the eyes of the mass public of Ireland in light of many, new economic realities.

European integration and governance have been centrally important in the economic transformation of Ireland, particularly through the alignment of state strategy with the action of economic and social interests. Given the current economic context, inequality not only heightens individual level concerns about economic stability, but it has also demonstrated that context, especially in the case of Ireland, is important and has directly influenced politics. As well as economic recovery, the majority of Irish individuals want an even distribution of growth (i.e. inequality should be addressed) and therefore by addressing inequality, democratic political institutions (i.e. in this case, the EU), should gain more support from Irish mass public opinion, making perceptions of inequality a noteworthy determinant of EU support in Ireland.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided helpful and worthy comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Social Partnership is the term used for the tripartite, triennial national pay agreements reached in Ireland. The process was initiated in 1987 after a period of high inflation and weak economic growth. This led to increased emigration and unsustainable government borrowing and national debt. Strike and wage moderation have been important outcomes of the Social Partnership agreements and are seen as a significant contributor to the Celtic Tiger.

2 It was intended to use EES 2014 data in conjunction with EES 2009 in order to examine change in attitudes towards the EU since the onset of, and after, the economic and financial crisis. However, using 2014 European Election Studies (EES) data is problematic and analytically hazardous owing to changes in the nature and the availability of many of the necessary variables. Only half of the dependent variables are included, more than half (56 per cent) of the independent variables are operationally different, while 19 per cent are missing entirely. This introduces substantial opportunity for both measurement error and omitted variable bias. Therefore, regrettably the OLS Multiple Regression model was not conducted with EES 2014 data.

3 OLS Multiple Regression analysis is the most widely used type of regression to incorporate two or more explanatory variables (i.e. the focus in this analysis on the central independent variable of inequality) in a prediction equation for a response variable (i.e. support for the EU). OLS Multiple Regression modelling is a mainstay of statistical analysis as a result of its power and flexibility to estimate complex models with large numbers of variables as demonstrated in the analysis here. All categorical/ordinal variables in the analysis are treated as continuous variables. Treating the variables in this way produced substantively the same findings in both models (OLS Multiple Regression and the Ordered Logistic Regression). Please see appendix for further details.

An Ordered Logistic Regression model is also conducted using EES 2009 data. The findings from the Ordered Logistic Regression model produced substantively the same findings as the OLS Multiple Regression model and thus for ease of interpretation only OLS Multiple Regression findings are discussed here. Please see appendix for Ordered Logistic Regression findings.

4 More generally, popular dissatisfaction with the functioning of democracy tends to produces a desire for more, rather than less, democracy (Dalton, Citation2005; Norris, Citation1999).

5 Note that the question here asks ‘Income and wealth should be redistributed towards ordinary people’ making no reference to country, party or specific policy.

6 Question QC3 in Eurobarometer 72 & 74, Question QB3a in Eurobarometer 73, Question QC3a in Eurobarometer 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 81, Question QC2a in Eurobarometer 80. Data unavailable for Eurobarometer 82 & 83. Please see http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/eb_arch_en.htm.

References

- Adshead, M., & Tonge, J. (2009). Politics in Ireland: Convergence and divergence in a two-polity Island. Basingstoke: Palgrave and Macmillan.

- Anderson, C. J., & Kaltenhaler, K. C. (1996). The dynamics of public opinion toward European integration, 1973–93. European Journal of International Relations, 2(2), 175–199.

- Anderson, C. J., & Reichert, S. (1995). Economic benefits and support for membership in the E.U.: A cross-national analysis. Journal of Public Policy, 15(3), 231–249.

- Bartels, L. M. (2008). Unequal democracy: The political economy of the new gilded age. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bernhagen, P., & Chari, R. (2011). Financial and economic crisis: Theoretical explanations of the global sunset. Irish Political Studies, 26(4), 455–472.

- Bollen, K. A., & Jackman, R. W. (1985). Political democracy and the size distribution of income. American Sociological Review, 50(4), 438–457.

- Boomgaarden, H. G., Schuck, A. R. T., Elenbaas, M., & de Vreese, C. H. (2011). Mapping EU attitudes: Conceptual and empirical dimensions of Euroscepticism and EU support. European Union Politics, 12(2), 241–266.

- Brinegar, A. P., & Jolly, S. K. (2005). Location, location, location: National contextual factors & public support for European integration. European Union Politics, 6(2), 155–180.

- Brinegar, A. P., Jolly, S. K., & Kitschelt, H. (2004). Varieties of capitalism and political divides over European integration. In G. Marks & M. R. Steenbergen (Eds.), European integration and political conflict (pp. 62–93). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carrubba, C. J. (2001). The electoral connection in European Union politics. The Journal of Politics, 63(1), 141–158.

- Chari, R., & Bernhagen, P. (2011). Financial and economic crisis: Explaining the sunset over the Celtic Tiger. Irish Political Studies, 26(4), 473–488.

- Corneo, G., & Gruner, H. P. (2002). Individual preferences for redistribution. Journal of Politics, 83(10), 87–107.

- Dalton, R. J. (2005). The social transformation of trust in government. International Review of Sociology, 15(1), 133–154.

- Dellepaine, S., & Hardiman, N. (2012). Governing the Irish economy: A triple crisis. In N. Hardiman (Ed.), Irish governance in crisis (pp. 83–109). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- de Vreese, C. H., & Boomgaarden, H. G. (2005). Projecting EU referendums: Fear of immigration and support for the European Union. European Union Politics, 6(1), 59–82.

- Eichenberg, R., & Dalton, R. J. (2007). Post-Maastricht blues: The transformation of citizen support for European integration 1973–2004. Acta Politica, 42, 128–152.

- Eichenberg, R. C., & Dalton, R. J. (1993). Europeans and the European community: The dynamics of public support for European integration. International Organization, 47(4), 507–534.

- Eurofound. (2012). Experiencing the economic crisis in the EU: Changes in living standards, deprivation and trust. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Retrieved from https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_files/pubdocs/2012/07/en/1/EF1207EN.pdf

- Finseraas, H. (2012). Poverty, ethnic minorities among the poor and preferences for redistribution in European regions. Journal of European Social Policy, 22(2), 164–180.

- Franklin, M., Van der Eijk, C., & Marsh, M. (1995). Referendum outcomes and trust in government: Public support for Europe in the wake of Maastricht. West European Politics, 18(3), 101–117.

- Gabel, M. (1998). Public support for European integration: An empirical test of five theories. The Journal of Politics, 60(2), 333–354.

- Gabel, M., & Palmer, H. (1995). Understanding variation on public support for European integration. European Journal of Political Research, 27(1), 3–19.

- Gabel, M., & Whitten, G. (1997). Economic conditions, economic perceptions & public support for European integration. Political Behavior, 19(1), 81–96.

- Garry, J. (2013). Direct democracy and regional integration: Citizens’ perceptions of treaty implications and the Irish reversal on Lisbon. European Journal of Political Research, 52, 94–118.

- Garry, J., Marsh, M., & Sinnott, R. (2005). ‘Second-order’ versus ‘issue-voting’ effects in EU referendums. European Union Politics, 6(2), 201–221.

- Gilland, K. (2002). Ireland and European integration. In K. Goldmann & K. Gilland (Eds.), Nationality versus Europeanisation: The view of the nation in four countries (pp. 166–184). Stockholm: Department of Political Sciences, Stockholm University.

- Glencross, A., & Trechsel, A. (2011). First or second order referendums? Understanding the votes on the EU constitutional treaty in four EU member states. West European Politics, 34(4), 755–772.

- Holmes, M. (2005). Irish approaches to European integration. In M. Holmes (Ed.), Ireland and the European Union (pp. 1–14). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Hussey, G. (1993). Ireland today: Anatomy of a changing state. London: Penguin.

- Kaltenhaler, K., Ceccoli, S., & Gellneny, R. (2008). Attitudes toward eliminating income inequality in Europe. European Union Politics, 9(2), 217–241.

- Kennedy, F., & Sinnott, R. (2006). Irish social and political cleavages. In J. Garry, N. Hardiman, & D. Payne (Eds.), Irish social and political attitudes (pp. 78–94). Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

- Kennedy, R., & Sinnott, R. (2007). Irish public opinion toward European integration. Irish Political Studies, 22(1), 61–80.

- Kenworthy, L., & McCall, L. (2007). Inequality, public opinion and redistribution. Socioeconomic Review, 6, 35–68.

- Kirby, P., & Murphy, M. P. (2011). Towards a second republic: Irish politics after the Celtic Tiger. Ireland: Pluto.

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolszal, M., Bornschier, S., & Frey, T. (2008). West European politics in the age of globalisation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kuhn, T., & Stoeckel, F. (2014). When European integration becomes costly: The euro crisis and public support for European economic governance. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(4), 624–641.

- Laffan, B., & O’Mahony, J. (2008). Ireland and the European Union. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Loveless, M. (2010). Agreeing in principle: Utilitarianism and economic values as support for the European Union in central and Eastern Europe. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 48(4), 1083–1106.

- Loveless, M., & Rohrschneider, R. (2008). Public perceptions of the EU as a system of governance. Living Reviews in European Governance, 3(1), 34.

- Lyons, P. (2008). Public opinion, politics in contemporary Ireland. Dublin: Irish Academic Press.

- Matthews, A. (1983). The economic consequences of EEC membership for Ireland. In D. Coombes (Ed.), Ireland and the European communities: Ten years of membership (pp. 110–132). Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

- McLaren, L. (2002). Public support for the European Union: Cost/benefit analysis or perceived cultural threat? The Journal of Politics, 64(2), 551–566.

- McLaren, L. (2004). Opposition to European integration and fear of loss of national identity: Debunking a basic assumption regarding hostility to the integration project. European Journal of Political Research, 43(6), 895–912.

- Norris, P. (Ed.). (1999). Critical citizens: Global support for democratic governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rehm, P. (2009). Risks and redistribution: An individual-level analysis. Comparative Political Studies, 42(7), 855–881.

- Reuveny, R., & Li, Q. (2003). Economic openness, democracy and income inequality: An empirical analysis. Comparative Political Studies, 36(5), 575–601.

- Rohrschneider, R. (2002). The democracy deficit and mass support for an EU-wide government. American Journal of Political Science, 46(2), 463–476.

- Rohrschneider, R., & Loveless, M. (2010). Macro salience: How economic and political contexts mediate popular evaluations of the democracy deficit in the European Union. The Journal of Politics, 72(4), 1029–1045.

- Rohrschneider, R., & Whitefield, S. (2006). Political parties, public opinion and European integration in post-communist countries: The state of the art. European Union Politics, 7, 141–160.

- Simpson, K., & Loveless, M. (2017). Another chance? Concerns about inequality, support for the European Union and further European integration. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(7), 1069–1089.

- Sinnott, R. (1995). Knowledge of the European Union in Irish public opinion: Sources and implications. Institute of European Affairs (IEA), Occasional Paper No. 5. Dublin Institute European Affairs.

- Sinnott, R. (2002). Cleavages, parties & referendums: Relationships between representative and direct democracy in the Republic of Ireland. European Journal of Political Research, 41, 811–826.

- Sinnott, R. (2005, June 14). Uphill task to win EU treaty poll here. The Irish Times.

- Szelenyi, I., & Kostello, E. (1996). The market transition debate: Toward a synthesis? American Journal of Sociology, 101(4), 1082–1096.

- Whitefield, S., & Loveless, M. (2013). Social inequality and social conflict: Evidence from the new democracies of central and Easter Europe. Europe-Asia Studies, 65(1), 26–44.

Appendix

Ordered logistic regression model and findings

An Ordered Logistic Regression model was also conducted using EES 2009 data. The findings from the Ordered Logistic Regression model produced substantively the same findings as the OLS Multiple Regression model with the central independent variable of address inequality performing the same across all three models of EU support. When examining both models, in the Ordered Logistic Regression model, there are only six variables (out of seventeen) which do not produce the same correlation and only two variables (out of seventeen) which do not have the same statistical significance as the OLS Multiple Regression model.

Only one of the Communication variables, (social communication is positively correlated with EU Good or Bad and EU in Ireland’s interests) diverges from the OLS Multiple Regression model but it is not statistically significant and thus has no impact on the findings. For the Ideological Congruence & Institutional Performance variables, prospective socioeconomic evaluation produces the most significant finding being statistically significant with EU in Ireland’s interest. While this is a welcome finding, it does not improve the Ordered Logistic Regression model or change the findings of the analysis overall as other variables such as market preference (positively correlated) and satisfaction with democracy (not statistically significant) do not harbour the same results as the OLS Multiple Regression model. For the Socio-demographic variables, Age produces another significant finding (positively correlated and statistically significant) while Gender meanwhile is negatively correlated. Again, while the statistical significance of Age is a welcome finding, it does not change the findings of the analysis overall.

It is important to note that the Ordered Logit model produces substantively the same findings as the OLS Multiple Regression model demonstrating that for individuals in Ireland, evaluations of support for the EU are not only economic but socio-tropic with many Irish people believing that the liberal market system functions in an unfair and unjust manner as they assess societal differences based upon both access and opportunity to the EU. This is reiterated by all of the theoretically relevant variables in both models and demonstrates the robustness of this analysis.

Measurement appendix:

The European Election Studies (2009) is a replication of the 2004 surveys (and previous elections back to 1979) in all EU member countries. European Parliament Election Study 2009, Voter Study, Advance Release, 7 April 2010. European Parliament Election Study 2009 [Voter Study] Advance Release 16/04/2010 (www.piredeu.eu).

Dependent variables:

EU membership: good or bad (q79): Generally speaking, do you think that [country’s] membership of the European Union is a good thing, a bad thing, or neither good nor bad? RC: Good thing, Neither, Bad thing. Reverse coded to make findings intuitive, DK to missing.

EU enlargement is good or bad (q83): In general, do you think that enlargement of the European Union would be a good thing, a bad thing, neither good nor bad. RC: Good thing, Neither, Bad thing. Reverse coded to make findings intuitive, DK to missing.

EU in our interest (q91): How much confidence do you have that decisions made by the European Union will be in the interest of [country] is great deal of confidence, a fair amount, not very much, no confidence at all. Reverse coded to make findings intuitive, DK & Refused to missing.

Independent variables:

Inequality

Address inequality (q63): Income and wealth should be redistributed towards ordinary people. RC: Strongly Agree, Agree, Neither, Disagree, Strongly Disagree. Reverse coded to make findings intuitive, DK/NA recoded to Neither.

Communication:

Social communication (q18): How often talk to friends/family about election? Often, Sometimes, Never. Reverse coded to make findings intuitive, DK to missing.

Mass media (q16 + q17 + q20): How often watch programme about election on TV (q16)/read about election in newspaper (q17)/ look into website concerned with election (q20) Often, Sometimes, Never. Reverse coded to make findings intuitive, DK to missing. Simple arithmetic sum of the three.

Political interest

Interest in politics (q78): To what extent would you say you are interested in politics? RC: Very, Somewhat, a little, not at all. Reverse coded to make findings intuitive, DK to missing.

Identity:

European identity (q82): Do you feel not only [country] citizen, but also a European citizen? RC: Nationality only, Nationality and European, European and Nationality, European only. DK to missing.

Cultural fear (q67): Immigration to [country] should be decreased significantly. RC: Strongly Agree, Agree, Neither, Disagree, Strongly Disagree. Reverse coded to make findings intuitive, DK/NA recoded to Neither.

Ideological congruence and institutional performance:

Retrospective sociotropic economic evaluation (q48): RC: A lot better, a little better, stayed the same, a little worse, a lot worse. Reverse coded to make findings intuitive, DK to missing.

Prospective sociotropic economic evaluation (q49): RC: A lot better, a little better, stayed the same, a little worse, a lot worse. Reverse coded to make findings intuitive, DK to missing.

Market preference (q57): Private enterprise best way to solve [country’s] economic problems. RC: Strongly Agree, Agree, Neither, Disagree, Strongly Disagree. Reverse coded to make findings intuitive, DK/NA recoded to Neither.

Satisfaction with democracy (q84): How satisfied are you with democracy in [country]? RC: Very satisfied, fairly satisfied, not very satisfied, not at all satisfied. Reverse coded to make findings intuitive, DK to missing.

Socio-demographic variables:

Age (q103): Year of Birth. Transformed: 2009-q103 to give age.

Gender (q102): Recoded 0 = Female, 1 = Male

Left-right self-placement (q46): RC: 0 Left – 10 Right. Coded into Left (0, 1, 2, 3), Centre (4, 5, 6), and Right (7, 8, 9, 10) dummy variables.

Education (v200): RC: ISCED (0) Pre-primary level of education;’ (1) Primary level of education; (2) Lower secondary level of education; (3) Upper secondary level of education; (4) Post-secondary, non-tertiary level of education; (5) First stage tertiary education; (6) Second stage of tertiary education (leading to an advanced research qualification) of education.

Social class (q114): RC: Working class, Lower middle class, Middle class, Upper middle class, Upper class. Other/Refused/DK coded to missing.

Subjective standard of living (q120): RC: Poor family (1) – Rich family (7). DK to missing