ABSTRACT

We empirically identify the considered views of the Northern Ireland public on the relative merits of two possible models of a united Ireland: an integrated united Ireland in which Northern Ireland is absorbed into an all-island polity, and a united Ireland in which Northern Ireland continues to exist as a devolved entity. We use data from a specially designed one-day citizens’ assembly. We report analyses based on quantitative examination of pre- and post-deliberation surveys and qualitative analysis of the transcripts of participants’ deliberation. We find that, after learning about the different two models, citizens’ support for the devolved model declined, particularly among Protestant participants. We elaborate the implications of our findings for any referendum on the constitutional future of Northern Ireland.

1. Introduction

In a referendum it is wise to be clear about the meaning of the choice posed to voters. Are they choosing between two well-defined alternatives, A or B, or between the status quo and an ambiguous alternative, A or not-A? Although a majority within the UK in June 2016 voted to ‘leave the EU’, with majorities in Scotland and Northern Ireland dissenting, the result has triggered three years of intense argument about what leaving the EU should mean. Such post-referendum confusion and acrimony regarding the meaning of the alternative to the status quo could be equally, if not more, problematic in a future referendum on Northern Ireland’s constitutional status.

Such a referendum, frequently and misleadingly referred to as a ‘border poll,’ is typically characterised as offering a choice between staying in the UK or leaving the UK to reunify with the rest of Ireland. But if a referendum is held in Northern Ireland within the next decade, and a majority there vote for Irish re-unification, the question obviously arises: what would that mean? Would it be clear what version of a re-united Ireland would be on offer before the referendum, or would determining that precise model be left to subsequent negotiation and bargaining? The grave challenge of specifying, operationalising, and debating exactly what reunification may mean is the subject of this article. Do unionists and nationalists know what a re-unified Ireland will mean? Do Protestants in particular have firm views on what many among them have regarded as an unpalatable choice? If they were obliged to choose, what version of a united Ireland would they prefer to live under?

We contribute to debate and planning for clarifying any future referendum choice by specifying the two most plausible potential models of a re-unified Ireland, and we identify the current considered views of the people of Northern Ireland on the relative merits of each of these two models. The first model is an integrated united Ireland, essentially a unitary state in which Northern Ireland ceases to exist, being absorbed into an all-island polity governed from Dublin’s parliament and executive, overseen by its courts (‘Integrated model’). The second model is a united Ireland in which the bulk of the arrangements of the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) are preserved, but transferred to Irish sovereign authority: Northern Ireland continues to exist, albeit now as a devolved entity within a sovereign Ireland, with a continuation of its current power-sharing arrangements and with the current powers of the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive intact (‘Devolved Northern Ireland /GFA model’).

To identify citizens’ considered views, we conducted a one-day citizens’ assembly in Belfast at which a cross-section of the Northern Ireland population listened to presentations, engaged in discussion and deliberation, and indicated their informed and considered views on the two possible models of a ‘united Ireland’. Briefly stated, our results are as follows. At the start of the day support for a united Ireland with a devolved Northern Ireland on the lines of the GFA was much higher than support for an integrated united Ireland. But, by the end of the day, support for a united Ireland with a devolved Northern Ireland had declined to the same level as support for an integrated united Ireland. This change in support was most pronounced among Protestant participants. Although perceived as ostensibly a ‘soft’, inclusive, or compromise option, some thought that the transferred Good Friday model was unlikely to work politically because the power-sharing arrangements were not functioning, and in their view showed little promise of reliable functioning; the different policy powers in the different parts of the island were judged likely to cause confusion; and, indeed, some thought that because this model is neither the status quo nor a fully-fledged united Ireland, it is unlikely to satisfy either nationalists or unionists and would hence prompt further acrimony and conflict. Relatedly, other participants saw such an arrangement as transitional – a ‘semi-skimmed’ united Ireland– one that would not last.

The remainder of this paper is organised to maximise clarity on these findings. We begin by elaborating on the different models of a united Ireland that we presented to the participants in the citizens’ assembly. We then describe the structure and organisation of the citizens’ assembly, and in the subsequent section report our quantitative and qualitative findings. In our conclusion we suggest that our analysis can help anchor the emerging debate about the nature of any potential referendum. Our aim is to facilitate policy-makers by providing a preliminary mapping of models and their current perceived merits and demerits. We aim to provide considerations to support further serious reflection on how to specify the choice(s) in any future referendum, and how to avoid post-referendum confusion about the meaning(s) of the alternative to the status quo.

Our analysis contributes directly to the understanding of unionism(s) in a time of change. We know of no previous deliberative forum which has sought to explore the views of Protestant and unionist citizens on possible versions of a united Ireland. We interrogate the views of people in Northern Ireland towards a change from the status quo (union with Great Britain and the European Union), to different possible unions, all-Ireland unions, as fleshed-out alternatives to the status quo. What are people’s views towards transition to an Irish union based on full integration, and the elimination of Northern Ireland? What are their views towards a model of all-Ireland union which would involve considerable continuity with Northern Ireland’s current political system? The vote in one union, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, to exit another union, the EU, has raised the salience of a possible vote to recreate an all-Irish union, so the analysis is topical.

2. Models of Irish unity

In systematically addressing the question of different possible models of Irish unity we must simultaneously accomplish two tasks. We wish to contribute to debate on how usefully to understand different models of a united Ireland, and, crucially, to report how exactly we informed the citizens who participated in our one-day citizens’ assembly.

We began our presentation to the participating citizens by outlining the constitutional status quo (for general background on the Northern Ireland conflict, see Aughey, Citation2005; McGarry & O’Leary, Citation1995; McKittrick, Citation2012; O’Leary, Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2019c, Vols. 1–3; Ruane & Todd, Citation1996, Citation1999). The status quo in UK law is based on the GFA, and endorsed in the double referendum of May 1998 in both parts of Ireland. Its fundamental premise is that a majority in Northern Ireland has the legal right to determine whether the region remains within the United Kingdom, or reunifies with sovereign Ireland. There is no legal right to independence for Northern Ireland. The relevant majority to whom the principle of consent applies is a majority of the people in Northern Ireland entitled to vote; the decision-rule is clearly defined as 50% +1 in a valid poll. That is the constitutional status quo in the UK, the position from which discussion and organisation of a referendum would start.

The Northern Ireland Secretary of State is obliged to trigger a referendum if, in her view, ‘a majority of those voting would express a wish that Northern Ireland should cease to be part of the United Kingdom and form part of a united Ireland’, and in the event of a vote for reunification she must legislate to give effect to that wish after negotiations between the UK and Ireland (Northern Ireland Act, 1998, Part 1, section 1, and schedule 1; for the question more generally, Coakley, Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Gibbons, Citation2018; Ó Beacháin, Citation2019).

The position in the Republic may be less well known, especially in Northern Ireland. Article 3. 1 of the modified Irish Constitution opens with a strong affirmation of a preference for unity with full respect for diversity:

It is the firm will of the Irish Nation, in harmony and friendship, to unite all the people who share the territory of the island of Ireland in all the diversity of their identities and traditions …

… recognising that a united Ireland shall be brought about only by peaceful means and with the consent of a majority of the people, democratically expressed, in both jurisdictions on the island.

So, for Irish re-unification to happen, under Irish law, it would seem that there has to be a majority of 50% +1 in Northern Ireland, matched by a majority of 50% +1 in a referendum in the Republic of Ireland. In short, Irish reunification requires concurrent consent. That is the Irish constitutional status quo from which would proceed referendums on re-unification. Logically, the appropriate sequence of referendums would be to start in the North, followed by one in the South, but if and only if the North has voted for reunification.Footnote1

2.1. Irish unity: elements of continuity

We emphasised to those participating in the citizens’ assembly that some matters would stay the same under any conception of a united Ireland. The GFA is not just an agreement that applies within Northern Ireland, it is protected by an internationally binding treaty between the United Kingdom and Ireland, and some of its key provisions would continue to apply even if Northern Ireland became part of a reunified Ireland (see Humphreys, Citation2018; O’Leary, Citation2019c, Vol. 3). Some core arrangements – not necessarily all – would remain the same, though there would be some role reversals.

Notably, the government of Ireland would be solemnly obliged to conduct itself impartially across the different national and political traditions that exist in the island – the British tradition, the Irish tradition, the Northern Irish tradition, those who prefer to have no tradition – and over those who have different religions and those who have none. This obligation would remain the same, though in this case sovereign responsibility would have passed from the UK to Ireland.

Citizenship rights would remain the same. Under the GFA, the natural presumption is that British citizenship is guaranteed forever to those born or validly naturalised in Northern Ireland irrespective of whether Northern Ireland is in the UK or becomes part of the Republic of Ireland (see Meehan, Citation2014). The Northern Irish would continue to be entitled to British or Irish citizenship, or both. Fundamental human and minority rights protections would remain the same. The Irish Government is committed by treaty to the GFA: Ireland thereby has to protect the rights embedded in the GFA itself, as well as the rights embedded in the European Convention on Human Rights, and the rights – particularly the non-discrimination rights – currently embedded in EU law (McCrudden, Citation2017). The Common Travel Area within the islands of Great Britain and Ireland would probably remain the same (for background, see Ryan, Citation2001). Both governments renewed their commitment to that Common Travel Area on 8 May 2019, even though the UK currently plans to leave the EU (Maher, Citation2017; Ryan, Citation2016).

Some fundamental institutional architecture of the GFA, according to international law, would remain in existence, unless both sovereign governments mutually agreed to changes (for an outline, see Coakley, Citation2014; O’Leary, Citation2019c, Vol. 3; Todd, Citation2017). The British–Irish Council, which links the governments of Ireland and of the UK, all of the current devolved governments inside the UK, and the insular dependent territories of the Crown – Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man – would continue to exist after Irish reunification. The British–Irish Inter-governmental Conference, in which the sovereign governments address matters that are not exclusively devolved to Northern Ireland, would continue unless the two governments modified their treaty arrangements. There would, however, be a role reversal: the government of the UK would have a special responsibility for representing the interests of the British people of Northern Ireland in a united Ireland, just as at present the government of Ireland has a special interest in representing the interests of Irish people inside Northern Ireland.

2.2. Irish unity: elements of change

Significant changes would also be likely in any united Ireland scenario. For example, Article 29 of the Irish Constitution permits Ireland to rejoin the Commonwealth, which it left in 1949 when the British resisted having republics as members. Shortly after Ireland’s departure, India became a republic, while remaining in the Commonwealth. Since then, the Queen’s role as Head of the Commonwealth has been separated from her role as head of state for many of its constituent members. Thus it is possible that in the future Ireland might rejoin the Commonwealth, of which the British Crown would probably continue to be symbolic head.

It is generally agreed that there will be economic changes if there is Irish reunification. But there is a debate about the economics of reunifying Ireland, on which we take no definitive view here, and took no view in the deliberative forum. One side effectively suggests that the South cannot afford the North – the North would be too expensive for its taxpayers, at least if they were to be supported at current levels of public expenditure. This perspective emphasises that the North benefits dramatically from what is called ‘the British subvention,’ i.e. the gap between what is raised in taxation in Northern Ireland and what is spent there by the UK state. This side tends to say that a united Ireland is economically impossible. The alternative perspective, by contrast, emphasises that Ireland is now richer in income per head than the UK however the data are crunched, whether by per capita gross domestic product or gross national income. In this view, precisely because Ireland is much, much richer than it was, it could afford reunification. This side usually claims that the subvention is exaggerated, and that some public expenditures would no longer be required. Moreover, this side argues that Northern Ireland would now strongly benefit economically from being disconnected from Great Britain to become part of a more dynamic, high growth economy in Ireland, an argument some claim is likely to be even more compelling with the UK’s departure from the EU.

We did not decide, nor did we ask participants to decide, which of these perspectives is correct, or closer to the truth, even though such arguments would figure prominently in a referendum. We also did not prevent or inhibit participants from discussing these perspectives. We did, however, ask them to make an assumption, namely that, in the short run, a reunited Ireland would make only a small difference economically. Within the North some would be better off, some would be worse off, but in general there would not be a massive transformation. There would, however, be one major economic change if Ireland reunified. The currency across the island would be the Euro, and Sterling would cease to be the operative currency in Northern Ireland.

Participants were advised that political and legal arrangements would be very different from the outset of a united Ireland. First, the Constitution of Ireland would apply throughout the island and its territorial waters, and that would apply the moment Irish reunification took place. That does not mean, of course, that the Irish Constitution cannot be changed; but changes would require constitutional amendments. Second, upon Irish re-unification, Northern Ireland would immediately return to the European Union, just as East Germany immediately became part of Germany and the Union upon German reunification. That prospect has been confirmed unequivocally by a decision of the European Council’s leaders that is binding in international law. That would mean that European Union law applied in Northern Ireland as well as, obviously, in the rest of Ireland. Third, if Irish reunification takes place, then Northern Ireland would no longer be part of NATO. Although Ireland is not part of NATO, and is formally militarily neutral, it is a member of Partnership for Peace, and its security co-operation with the rest of the EU has been steadily changing and deepening. Fourth, in Northern Ireland, the Head of State would change, with the President of Ireland now taking on this role.

A series of more mundane institutional changes were also predicted. In Northern Ireland, TV and radio licence fees would be paid to Raidió Teilifís Éireann, not to the BBC. The British Honours system – Knighthoods, CBEs, MBEs, and so on – would no longer apply. All national sports teams would be all-island (though currently there is only one major exception to unified Irish teams in competitive field sports, namely in soccer). The Irish Army would voluntarily incorporate any serving soldiers inside the existing British Army who came from Northern Ireland, but it would be the Irish Army. Such independent public bodies as the Irish Central Bank would apply their powers across the island.

Participants were advised of further significant changes to government that would affect the North. The Irish Supreme Court adjudicates the Irish Constitution and related questions that come before it. The composition of the Supreme Court would be expanded to include a representative set of judges from Northern Ireland. For all of Ireland, monetary policy would be set by the European Central Bank – including the interest rate that applies in banks, and affects mortgages and the price of loans. The big questions on taxation would rest with Dáil Éireann, as guided by the Irish Government, notably regarding income tax and VAT. The low corporate tax rate to encourage inward investment that applies to multi-national companies would presumably be the same across Ireland. The Irish Senate would continue to exist, but there would be new senators in proportion to the existing North’s share of the overall Irish population. Very importantly, representatives from Northern Ireland would now sit in an all-island parliament in Dublin.

Participants were guided as to likely initial party configurations in an all-island parliament. We projected from existing party shares in the North and the South, based on recent elections to Dáil Éireann and to the Northern Ireland Assembly – emphasising that the projection could not be taken as an absolutely reliable guide to outcomes. Participants saw that a significant share of the overall all-island vote would be held by three large parties, Fine Gael, Fianna Fáil, and Sinn Féin; and that the DUP would be the next largest party. We provided a crude indicator of the relative influence of ‘cultural Protestant’ voters, i.e. those of Protestant background in either part of the island, but now combined within a united Ireland. We stated that Protestant political preferences would likely be spread across many political parties on the island, not just the DUP or the UUP. Some would support the Alliance Party, some the Greens, some other parties of the left, and so on. The one in six ratio was provided as our rough estimate of the proportionate influence of cultural Protestants in an all-island parliament.

Having introduced the constitutional status quo, and indicated what would continue and what might change in a reunified Ireland, we presented in detail two possible models of a united Ireland that might be on offer in a referendum, an integrated united Ireland and a united Ireland with a devolved Northern Ireland. (We also presented two further theoretically possible models, federation and confederation, but argued that they were unlikely to be on offer in a referendum: see supplemental data for full details of our discussion of this point.)

2.3. Exploring the integrated model

Participants were told that in an integrated Ireland, Northern Ireland would be voluntarily absorbed into a unitary Irish state after the two referendums. What that would mean was spelled out. The laws that apply in the Republic, its institutions, its public agencies, and its public services would be extended to cover what is now Northern Ireland. There would be some necessary transitional arrangements, and these would be subject to northern influence through the presence of northern deputies in the Irish parliament. But the key reality would be that the existing Irish set of laws, the Irish statute book, and European Union law would all apply, except where transitional arrangements are needed. The transitional arrangements would be negotiated by the British and Irish governments and, if it was functioning, the Northern Ireland Executive.

Such symbols as, the national flag and the national anthem of Ireland in the short run could remain as they are now but, so far, all of the major parties in the South, including Sinn Féin, have signalled that these would be up for negotiation in such a changed political context. Provisionally, however, the existing symbols, national flag and national anthem would stay. Some features of the GFA would continue to apply: the Irish government would be obliged to display ‘rigorous impartiality’ in respect of the two communities in Northern Ireland.

There would be a decisive impact on political institutions in the North, however. Northern Ireland, as such, would cease to exist. There would be an all-island parliament in Dublin. Government would be organised fundamentally at an all-island level. Local government would remain the same in the South, and probably remain the same in the North, in the short term. There could, however, be convergence towards the Southern model, namely county government would be restored, perhaps with separate city governments in Belfast, Craigavon, and Derry/Londonderry.

Very importantly, in an integrated Ireland, one would expect the Southern parties to organise in the North and some northern parties would seek to recruit voters in the South. There would be a quick move towards an all-island party system – a visible transformation in the eyes of most citizens. There would be a big change in the organisation of public services, policies and security in the North. There would be a common civil service: judging by what has happened in other reunification processes there would be a fusion of the civil services; the Northern Ireland civil service would be integrated into the Irish civil service. There would be some rationalisation (implying job cuts) where there would otherwise be duplication. Some civil service jobs would require competence in the Irish language as at present in the South, but that would be a selective requirement, not ubiquitous.

In this model, there would be an integrated health service. The same system that exists in the South would extend and apply in the North, no doubt, with transitional arrangements to allow for the different model that has applied in the North since 1945. There would be common provision for Catholic schools, Protestant schools, and non-denominational primary and secondary schools, similar to the model that applies in the North at the moment, with equal funding for each set of schooling arrangements. Universities and higher institutions of third-level education would be part of the same system, and subject to the same regulations. Over time there would be a single welfare system, a common set of pension arrangements in the public sector, and common regulation of private sector pensions, and the same kinds of benefits would apply throughout the island. No doubt, across several governmental and social policy sectors, negotiated transitional arrangements would cater for significant differences that have emerged in the two parts of the island over the century since partition, but in this model one would expect common environmental policies, common infrastructural policies for railways, roads, ports and airports, common urban planning policies, and so on. Fisheries and agricultural policy would be determined by the European Union.

These were not the sole developments to be expected. In an integrated Ireland, the Irish state’s fundamental rights provisions would apply across the island, as modified by the European convention and by the EU’s own law. Questions like abortion and the rights of same sex couples would, for example, be subject to the Irish Constitution and Supreme Court decisions in Dublin. There would be a fusion of the police services, the Police Service of Northern Ireland would be fused with the Gardaí in the South, and, because of the GFA, one would expect a common code requiring the police to respect both traditions, and those who belong to none. The Irish Army would be recruited on an all-Ireland basis, and unlikely to have a separate Northern Ireland regiment. People with British citizenship could serve in the Irish Army but at the very highest levels, in a typical reservation across Europe, only Irish citizens could serve as generals, and likewise operate in the highest echelons of the Irish Department of Defence and intelligence services.

2.4. Exploring the devolved model

Participants were then informed about the second model in some detail. The border would continue to retain some legal and institutional significance; of course, it would not be a hard border, marking a sovereign demarcation. But it would still matter because the Northern Ireland Assembly would exercise power inside Northern Ireland in those areas for which it was responsible. The Dublin Parliament would also exercise powers in Northern Ireland, crudely, as currently exercised by the London government. The Irish Constitution was designed to accommodate this possibility; as Article 15.2.2 states:

Provision may however be made by law for the creation or recognition of subordinate legislatures and for the powers and functions of these legislatures.

We addressed what this model would look like in more depth. Northern Ireland would continue to exist; its Assembly would perform certain key functions; and its existing statute book would remain in place, though subject to conformity with the Irish constitution. Roughly speaking, the Dublin parliament would have authority throughout the island in all those domains where British authority now applies in Northern Ireland: the currency, the head of state, foreign policy, and external relations. Otherwise, Northern Ireland’s existing legal arrangements would remain in place. Northern Ireland would have its own symbols, and it could have its own flag (the Ulster banner or some other agreed flag). It could have its own anthem. It could have different forms of territorial and indeed cultural autonomy. Different arrangements could apply for the Irish and the Ulster Scots languages compared to the rest of Ireland. The arts could be organised separately and differently funded in the North, and there could be separate public media organisation there.

Importantly, under this model some key functions would be in the hands of the Dublin parliament and the Dublin government, in which of course there would be northern participants, northern deputies, and very likely northern cabinet ministers. Income tax would almost certainly be set in Dublin, but just as Scotland has the right to vary income tax inside the United Kingdom, the same arrangements could apply for Northern Ireland: it could, for example, apply a plus or minus three percent of the rate applied in Ireland as a whole, with consequent implications for local expenditure, and borrowing. But we anticipated that the same corporate tax rate would apply throughout the island, enabling Ireland as a whole to offer the same attractions to external businesses that wish to invest.

Plainly the political institutions that have become familiar in Northern Ireland would remain similar to today: the Assembly elected by proportional representation, and the power-sharing executive determined by the d’Hondt rule. Some participants in our experiment rightly raised the point that ‘we don’t have any currently functioning institutions’. We concurred, but observed that these might be revived.Footnote2 Within the existing terms of the GFA, we observed that there are arrangements for review of how the Northern Executive and the Northern Assembly function, and mechanisms for modifying them to make them function more effectively.

We emphasised that in this model the expectation would be that the Northern Ireland Assembly would continue to exist, and continue to use the single transferable vote system of proportional representation (also used for elections to the Dáil). In a united Ireland, however, what is called ‘the West Lothian question’ in Great Britain would arise on a much bigger scale. We explained to participants that, as initially designed in the UK’s devolutionary arrangements of the late 1990s, Scottish MPs voted in the Westminster Parliament on laws that affected England and Wales, and indeed, Northern Ireland, but English MPs did not vote on matters devolved to the Scottish Parliament. We observed that this discrepancy would create a much bigger problem in a united Ireland, because Northern Ireland would be roughly one third of the population of a unified Ireland. We therefore predicted that deputies in Dáil Éireann would not vote on matters that are devolved to the Northern Ireland Parliament, and that northern deputies in the Dáil would not vote on matters within the current jurisdiction of the 26 counties.

If this model were to materialise, the Northern Ireland executive would continue with its two First Ministers, and ministries would continue to be allocated according to parties’ proportional strength in the Assembly. Northern Ireland would continue to have its own high court, but subject to the jurisdiction of the Irish Supreme Court, though that court would have judges from Northern Ireland. All of the institutions of the GFA would remain: the British–Irish Council, the British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference, and the North/South Ministerial Council. They could change the way they do their work, or their assigned functions, by agreement. A big difference that we said we expected to emerge from this model would be the continuation of distinct party systems, North and South, though Southern Parties would organise in the North, and no doubt some Northern parties would seek to operate in the South.

In our judgment, the Northern Ireland civil service would continue as at present without the same rationalisation that might occur in the integrated Ireland model, but subject to the financial discipline and the personnel authority of the Department of Finance in Dublin. Under this model, there would be the possibility of preserving quite distinct health systems, one that flows from the logic of the NHS in the North and the system that has developed in the South. Northern Ireland could retain its distinct educational system. People could do A-Levels and GCSEs rather than their southern counterparts. Their qualifications would of course be recognised throughout the island but also in Great Britain. The university sector and higher education would remain distinct, and would operate according to their own conventions and rules. We would also expect to see differences preserved in the management of planning, infrastructure and the environment, subject to some all-Ireland provisions.

As to other areas, fishing and agriculture would be primarily determined by the European Union. Questions of fundamental rights related to abortion and same sex marriage would be subject to Irish constitutional law and European human rights law. The Police Service of Northern Ireland would continue to exist, though for some matters it would come under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Justice in Dublin, and it might be possible to create a separate Northern Ireland regiment inside the Irish Army.

3. A citizens’ assembly

3.1. Rationale for a citizens’ assembly

To identify citizens’ considered reactions to these two models, we organised a citizens’ assembly on a modest scale. Our justification was clear: despite the fact that the constitutional distinction between staying in the UK or advocating a united Ireland is of long-standing and high salience in Northern Ireland, consideration of distinct possible models of a united Ireland has been rare. The issues are complex and novel to many, and hence a thoughtful and considered process of learning and deliberation is arguably appropriate (Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge, & Warren, Citation2018; Fishkin, Citation2009). Second, we wished to examine the dynamics of opinion formation. As citizens learn and deliberate about the different possible models of a united Ireland how, if at all, do their views evolve and change (O'Malley, Suiter, & Farrell, Citation2019)? Do they become more in favour of one particular model and less in favour of another, once they have had a chance to consider, discuss, and reflect on both? Measuring views before and after the citizens’ assembly allows us to identify evolution in opinion. Conducting a citizens’ assembly enables us to combine quantitative and qualitative evidence. Thematic interrogation of the deliberative transcripts of the citizen discussions contributes to a fleshed out and nuanced understanding and interpretation of quantitatively observed opinion change, allowing us to identify what it is about each of the models of a united Ireland that citizens find attractive, puzzling, problematic or anathema, once they have had a chance to learn about them and engage in discussion about them.

3.2. Organising a citizens’ assembly

Our one-day citizens’ assembly applied to the Northern Ireland setting the same methodological logic underlying previous citizens’ assemblies, such as the Irish Citizens’ Assembly 2016–18, albeit on a smaller scale.Footnote3 The one-day citizens’ assembly was held on 30 March 2019Footnote4 at the Clayton Hotel in Belfast, between 10am and 4pm. Forty-nine citizens attended the event (out of a planned attendance of 50). Participants were recruited to ensure that those who attended the event were broadly reflective of the demographic composition of Northern Ireland. A quota sampling approach was applied to several demographic variables, including gender, age, socio-economic group, community background and region (see for demographic breakdown).

Table 1. Demographic composition of citizens’ assembly.

As participants arrived, they were given a questionnaire to complete. The aim was to gain an understanding of participants’ views and attitudes on the topics before the day’s deliberations. The same questions would then be asked at the end of the day to determine whether there had been any shift in views as a result of the day’s presentations and discussions. The participants were seated around five round tables, with a demographic mix of participants at each table. They were briefly given an overview of the day, with assurances of confidentiality and anonymity regarding data collected by the managing director of Ipsos Mori Northern Ireland (the market research company commissioned to generate the sample and organise the logistics and facilitation of the event). Professor Garry then addressed participants to explain the purpose and structure of the day’s event.

During the morning session, the first presentation was delivered by Professor O’Leary.Footnote5 It began by highlighting possible lessons from the UK’s EU referendum, emphasising the importance of defining the alternative to the status quo in a referendum, and then, as detailed above, focused on what would remain the same under any model of a united Ireland, and what would be different under any model of a united Ireland.

The four different possible models of a united Ireland were then outlined. The focus was on the integrated model and Northern Ireland as a devolved part of a united Ireland as the two most plausible models. Following Professor O’Leary’s first presentation, the participants engaged in roundtable discussions to explore the topics addressed in the presentation in more detail, facilitated by Ipsos Mori moderators using pre-defined discussion guidelines.Footnote6 Discussions on the tables covered several topics: lessons from the EU referendum; whether a referendum on Irish unity is more or less likely as a result of Brexit; whether a referendum is a good or bad idea; whether or not Northern Ireland is prepared for a referendum; aspects of life that would remain the same under a united Ireland; and aspects of life that would change under a united Ireland.

This table discussion lasted approximately 45 minutes. Following the discussion, the moderators addressed the room, summarising the key points raised at each table. Participants were also invited to write down any questions that had arisen during the discussions, which the moderators passed onto Professor O’Leary who addressed them at the end of the day.

In the afternoon, Professor O’Leary delivered a second presentation. The presentation covered in detail the two different models of a united Ireland. Following the afternoon presentation, table discussions resumed. This time discussion focused on the two most likely models of a united Ireland. It explored preferences for remaining in the UK or joining a united Ireland; integration versus devolution; considering an integrated Ireland (likes, dislikes and areas of tolerance); and a devolved Ireland (likes, dislikes and areas of tolerance). Participants also completed an exercise in which they explored the different options that might be presented to the electorate if a referendum were to occur, identifying their ballot preference and then discussing it with other members of the table.

The main points discussed at each table were then fed back to the room through the moderators. Following all presentations and table discussions, Professor O’Leary spent 15 minutes answering a range of questions posed by the participants. Participants were then asked to complete a short questionnaire. The questions asked in the afternoon questionnaire were the same as those asked in the pre-questionnaire, with the aim of determining whether or not the information delivered to participants throughout the day had impacted their views and attitudes. At the end of the session participants were thanked for their contributions and compensated with £80 in thanks for their attendance.Footnote7

3.3. Operating a citizens’ assembly

The question of Irish unity and the prospect of a referendum on a united Ireland is a particularly contentious and sensitive subject in Northern Ireland. Using this research method therefore carries the risk that citizens would be unable to overcome their own personal views to have a constructive discussion. There were participants with strongly held views, but there were some individuals who, despite having strong views, were willing to engage with other members of the group, while others held very fixed positions and were not as open to debate. The moderators therefore steered conversations so that the more talkative participants did not create an imbalanced discussion.Footnote8

Despite having strong views, the participant was stating his opinion and wasn’t particularly rude or dismissive of anyone else who wished to voice their opinions.

Moderator of table 1

There were a couple of quieter individuals on the table - I think this may have been down to a combination of their individual personalities and a lack of strong opinions on the topics at hand. I was mindful to ask them for their views, at which point they were happy to contribute to the discussions.

Moderator of table 4

Further questions in the questionnaire at the end of the day sought to assess the extent to which participants evaluated the deliberations positively. Very high proportions of participants agreed with the statements: ‘I had ample opportunity to express my opinion during the discussions’ and ‘In general, everyone showed respect for the others in the discussion’.

In order to assess whether the citizens’ assembly had been successful in enabling participants to become more informed, one of the questions asked at the beginning and the end of the day was ‘In general, thinking about the issues relating to having a referendum in Northern Ireland and the choice between staying in the UK and a United Ireland, how informed do you think are about the issues right now?’, with response options ‘very well’, ‘fairly well’, ‘not very well’ or ‘not at all well’ informed (on a one to four scale, where higher scores indicated less knowledge). A paired-samples t-test was conducted to compare self-described knowledge level of the participants before and after the day’s deliberations. There was a significant difference in the scores knowledge level before (M = 2.92, SD = 0.79) and after (M = 2.48, SD = 0.94), t(47) = 3.214, p = 0.002. These results suggest that participating in the one-day citizens’ assembly increased participants’ knowledge of the issues relating to the topic of a referendum on Northern Ireland’s constitutional future.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative evidence

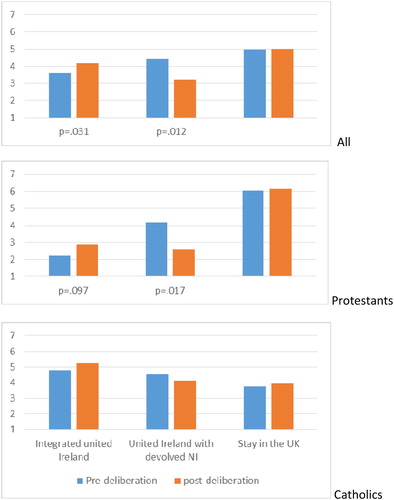

Participants were asked a set of identical questions at the beginning and the end of the day’s deliberations about the relative merits and demerits of staying in the UK, an integrated united Ireland and a united Ireland with a devolved Northern Ireland. In the first battery of questions participants were asked to indicate their level of opposition to or support for each option. The mean scores are reported in , broken down by all participants (top layer of the graph), Protestants participants only (middle) and Catholic participants only (bottom). The general pattern (for all, Protestants and Catholics) is increased support over the course of the day for an integrated united Ireland and a decrease in support for a united Ireland with a devolved Northern Ireland. The differences are statistically significant for all respondents and for Protestants only.

Figure 1. Pre-deliberation and post-deliberation mean support (on 1–7 scale) for integrated United Ireland, devolved United Ireland and staying in the UK – by all participants, Protestant participants and Catholic participants.

Note: statistically significant differences at .1 level or better are reported (paired sample t-tests); analysis excludes ‘don’t knows’, minimum N for all is 37, for Protestant is 18 and for Catholic is 17.

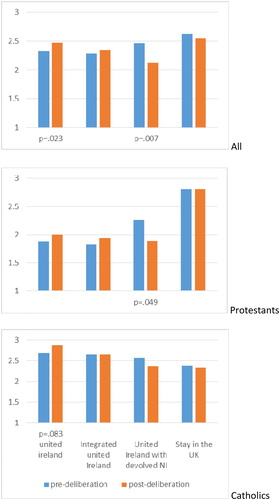

reports changes in the extent to which participants regard each constitutional outcome as acceptable if it were voted for in a referendum. Again, the direction of the effects for Protestants is an increase in acceptability of an integrated model and a decrease in acceptability of the united Ireland with a devolved Northern Ireland model, the latter difference being statistically significant.

Figure 2. Pre- and post-deliberation levels of acceptability of each constitutional possibility (on 1–3 scale, higher scores indicating more acceptable) – by all participants, Protestant participants, and Catholic participants.

Note: statistically significantly differences at .1 level or better are reported (paired sample t-tests); analysis excludes ‘don’t knows’, minimum N for all is 36, for Protestants is 17 and for Catholics is 16.

Overall, the interesting pattern that emerged was that for Protestants there was a reduction in positive evaluation of the united Ireland with a devolved Northern Ireland model, to a statistically significant extent at the .05 level across both measures (support and acceptability). Hence, at the start of the day, Protestants were considerably more in favour of the united Ireland with a devolved Northern Ireland option rather than the integrated united Ireland option, but at day’s end, Protestants were equally disposed towards both models of a united Ireland. It is equally noteworthy that there was an increase in acceptability, as seen in , of a united Ireland as measured in the general sense (i.e. not specified as either integrated or devolved), and this increase was in the same direction for both Catholics and Protestants, though only statistically significant (at .1 level) for Catholics.

4.2. Qualitative evidence

We now use our examination of the transcripts of the morning and afternoon round table discussions and deliberations to help make sense of the quantitatively observed patterns that have just been described. We must first emphasise that there is an enormous wealth of fascinating detail in the transcripts from discussions at all five tables during both sessions. We provide for the interested reader a thematic analysis of the entirety of the set of transcripts (see supplemental dataFootnote9).

In brief, the themes that emerged were as follows. There was negative assessment of the quality of the referendum campaign in 2016, characterised as ‘scaremongering’ with a lack of clear information. There was a prevalent view that the 2016 EU referendum had increased the likelihood of a referendum in Northern Ireland on its constitutional future, although many also felt that it depended upon how the issue of ‘Brexit’ was resolved. Some participants expressed concern that holding a referendum would be divisive and could lead to violence. Some felt there were benefits to holding a referendum, though many were of the view that Northern Ireland is not at all prepared for a referendum, and there was little appetite for an immediate referendum, with a five to ten year timeframe suggested by many. There was a consensus that in the event of a referendum being held there would have to be clear information, with serious efforts made to ensure that this was inclusive and as sensible as possible. Some emphasised that political debates in Northern Ireland are inevitably reduced to binary antagonisms – green versus orange –and some highlighted the need to frame future debates in non-binary terms. There was a clear feeling of antipathy to politicians generally, both in relation to the non-functioning executive in Northern Ireland and the manner in which the issue of Brexit was being handled in the UK. There was a related emergent theme of what we might call ‘anti-politics,’ a sense of disenfranchisement, and the underrepresentation of Northern Ireland, indeed a sense that Northern Ireland is politically peripheral, especially in relation to how politicians dealing with Brexit are treating Northern Ireland. When reviewing the different general options (of the status quo versus a united Ireland) there was a tendency to focus on the day-to-day implications rather than the somewhat abstract political and constitutional aspects, focusing on finance, health, jobs and education. When discussing preferences for remaining in the Union it was difficult for some participants to be quite clear as it was contingent upon how the Brexit question unfolded, while for others there was unequivocal support or opposition irrespective of the outcome. A theme emerging from discussion of a united Ireland in general was that it was closely linked in participants’ minds to the issue of the EU, and the possible hardening of the border, and for many Catholics the advantages of unity were linked to staying in the EU and avoiding border problems. Also, for some, discussion of a united Ireland generated the articulation of traditionally strong unionist or nationalist views, while others expressed surprise and an openness to learning about the range of options, and possibly having changeable views (typically from among those not identifying as either ‘nationalist’ or ‘unionist’).

Now we can specifically focus on how participants articulated their views on the two particular models of a united Ireland. Many participants were surprised that there was more than one possible way of thinking about a united Ireland.

The fact that there’s even different options. I would have thought the options would have been either you’re ruled by Ireland or you’re ruled by the UK; I wouldn’t have thought there would be a chance for a devolved Northern Ireland.

Male, 18–29, C2DE, Co. Derry/Londonderry, Catholic, very strongly nationalist

I think before you looked at it through the green or orange-tinted glasses […] and looked at it as united or not, and now, there’s different options that can be laid on because it’s for everybody.

T292, Male, 45–59, ABC1, Greater Belfast, Catholic, neither unionist nor nationalist

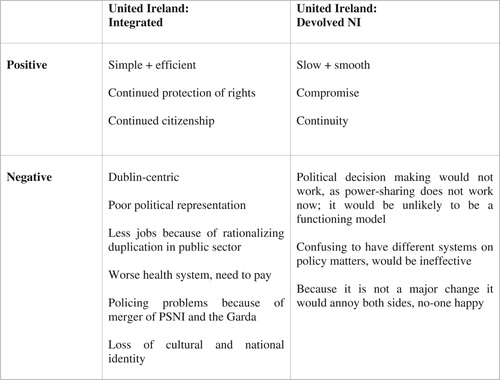

When participants considered some of the possible benefits of the integrated model, the advantage of it being simple and efficient was emphasised. There would be a single system and it appeared relatively easy to understand. One positive feature that surprised many participants was that it would involve a continuation of the rights that currently exist in Northern Ireland, and also that the option of remaining a British citizen would be available. Some citizens felt that this integrated model was in fact the traditional model of a united Ireland and were (positively) surprised that such a model would continue existing rights and citizenship provisions. The main negative features emphasised were that power would definitely be in Dublin, similar to the London focus of the current UK system, and that northern interests might be inadequately represented. The possible job losses in Belfast that might result from eliminating duplication in the public sector caused anxiety, as did the spectre of the Irish health system replacing the free NHS. Fears were raised about the tensions that might result from merging the PSNI with An Garda Síochána, and there was a general antipathy and fear, expressed by many Protestant participants, regarding the loss of their culture and identity.

Figure 3. Main perceived positive and negative aspects of each model of a united Ireland among participants.

One of the attractions noted about a united Ireland with a devolved Northern Ireland in accordance with the full GFA model was that it could provide a slow and smooth move, a soft transition, rather than radical overnight change. However, as participants reflected upon it, many highlighted the fact that the existing power-sharing arrangements are currently not working. Confusion may result; it might prove an unworkable compromise that would annoy both sides.

Given that opinion shift during the day was most evident in relation to the devolved model, we are particularly interested in identifying what considerations played a particularly significant role in swaying support. As reported, several participants had earlier highlighted the merits of this model, especially its gradualism, compared to the radical shift in the integrated model. It was also seen as an inclusive compromise by several participants, and hence attractive. But what seems to us to have driven critical re-appraisal was participants’ fear that this model would not work, both because of the current failure of power-sharing to function, and because the differences between Northern and Southern policies would lead to confusion.

Although I did say earlier that in order to maybe allay people’s fears I’d be happy with it, in order to bring people on board slowly and kind of work with it. But I think the more you look at it, the more you maybe break it down it probably would be too much work, too much going on. There’d be more focus on what people can’t do as opposed to what people actually can do.

Male, 45–59, C2DE, Co. Antrim, Catholic, fairly strongly nationalist

It’s never going to work. It doesn’t work now … I sort of think, well it says here in the second line, ‘if functioning’, I mean if we’re recognising here that it’s not working at the minute so to add more confusion … it’s just going to go nowhere and it’s just going to, again, be very difficult and it’s actually ruining it for the generation of people that don’t really care about the Troubles or the historic side of it.

Female, 30–44, ABC1, Derry/Londonderry, Protestant, Very strongly unionist

… my first choice would be to stay, but with the backstop in place, but, without that, and I’m choosing between these two options, it would be the fully integrated. The reasons being – for the devolved Northern Ireland … you would still have the same problems … they would still be voting for the red, white and blue or the green, white and gold … there would be slight changes done on the surface, but really you would still have exactly the same really … so therefore, why put the country through riots, fighting, shooting; violence coming back onto the street, for something that really, at the end of the day, is the same.

Female, 45–59, C2DE, Greater Belfast, Protestant, neither

… you’ve got one section of the community that want to remain in the United Kingdom, and you’ve got the other section who want to move to a united Ireland, and what I see with this particular model here is both cases, both people really losing … because on the unionist side, you’re essentially joining a united Ireland and you’re not under the Crown anymore, as such. Whereas on the nationalist side, they’re not getting full control of a united Ireland … and a fully devolved united government, and I think that … Nobody’s happy. So, you’re back to square one …

Male, 30–44, ABC1 Derry/Londonderry, Protestant, neither

We also examined the short qualitative responses that participants were asked to register in the survey at the end of the day, asking them to indicate the positive and negative features of the two different models of a united Ireland. Box 1 reports the negative views of the devolved model that were made by all Protestant respondents who moved at least one unit in a negative direction away from supporting this devolved model over the duration of the day. These participants highlighted the complexity of the model, the economic and identity-related uncertainty associated with it, the idea that very little would have changed, and that tensions and conflicts would have been reactivated.

‘Don't like this at all.’(general dislike)

‘I don't see much change - no one wins.’ (no change)

‘It's no change from what we already have.’(no change)

‘Job uncertainly, financial uncertainty, loss of identity.’ (uncertainty, identity)

‘Confusion over identity, could arise tensions.’ (uncertainty, identity, tension)

‘More complicated.’ (uncertainty)

‘Adds another level of difficulty, a diluted solution? Difficulty in working in partnership with Dublin. Would it be working with or against one another?’ (unworkable compromise)

‘Would only cause dissension between the leavers and the stayers.’(tension)

‘This could cause conflict to start up in the North. This has no benefit but gives more problems.’ (tension)

‘The devolved model would move the goal posts in regards to society in respect to the current situation of Northern Ireland devolved within the United Kingdom which has not been successful or beneficial to the people of the North of Ireland. Everyone is on a different starting point!’ (unlikely to be successful)

5. Conclusion

The Secretary of State for Northern Ireland has the power and duty to initiate a referendum on the constitutional status of Northern Ireland under certain conditions. If the likelihood of a referendum increases, there is likely to be increased focus on what the precise options should be for Irish reunification, and what they mean. Our examination of how citizens in Northern Ireland consider what we regard as the two initially most plausible institutional models suggests that the devolved Northern Ireland/GFA model has the potential to be initially regarded somewhat positively but then is likely to suffer a decline in support once deliberation has taken place over its merits. There is a less powerful tendency in the other direction for the integrated model.

Of course, there are limitations to our analysis, and serious constraints in our ability to infer smoothly from our citizens’ assembly context to the hurly burly of a real world referendum campaign. Instead, we have focused on what happens when citizens calmly reflect on the relative merits of a neutrally presented duo of possible outcomes. We have done so to ascertain what the considered views of the Northern Ireland population may be like. In an actual referendum campaign, political parties and the media, who were deliberately excluded from our deliberations, will be highly active and likely have significant influence on voters’ decisions. It is thus important to emphasise that our citizens’ assembly is not designed to predict exactly how a real world campaign would unfold, but rather to show what happens in a reasoned deliberative setting.

As well as contributing this clarification of the most plausible initial models of a reunified Ireland, and a preliminary assessment of citizens’ considered views on the two most plausible proposals, we believe that our experiment suggests that an enhanced version of our citizens’ assembly may be profitably conducted in the Republic of Ireland. The question of what union, if any, people in the Republic desire, and are willing to offer, is equally crucial to address. The range of possible Irish unions is equally relevant both sides of the border, to unionists and nationalists, and others. Any worthwhile referendum in Northern Ireland would have to match feasible expectations in the Republic.

The challenge of specifying exactly what model of an Irish union should be on offer in both jurisdictions is complex. If a specific model of re-union was voted on in the North, the same model of union would have to be voted on in the South. The type of union to offer voters, in the event of any referendum, has to be discussed throughout the whole island as well as in both current jurisdictions. Replicating the currently reported citizens’ assembly in the Republic would be of obvious merit. Subsequently conducting an all-island citizens’ assembly to assess the merits of many different types of unions should be considered: re-unions of Ireland, modifications to the union with Great Britain, modifications to both jurisdictions’ relationships with the European Union, and perhaps reversion to membership of the Commonwealth. This article summarises the first step in a research programme with important political implications.

Appendix B - Supplemental Material

Download MS Power Point (1.6 MB)Appendix A - Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (75 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

John Garry is Professor of Political Behaviour at Queen's University Belfast. His research interests focus on voting behaviour, public opinion, and deliberative democracy.

Brendan O'Leary is Lauder Professor of Political Science in the University of Pennsylvania and visiting Professor of Political Science at Queen's University Belfast. His research interests focus on Northern Ireland, civil conflicts, consociationalism and comparative federalism.

John Coakley is visiting Professor of Political Science at Queen's University Belfast and Professor Emeritus in Politics at University College Dublin. His research interests focus on Northern Ireland, North-South relations, and British-Irish relations.

James Pow is a lecturer in politics at Queen's University Belfast. His research interests focus on democratic innovations, civic engagement, political behaviour, and public opinion.

Lisa Whitten is a PhD student at Queen's University Belfast. Her research interests focus on Northern Ireland politics, constitutional law, and the politics of “Brexit”.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The implications of these provisions have not been explored in court. For example, it is not necessarily clear that the expressions ‘the consent of a majority of the people democratically expressed’ definitely requires a referendum, nor is it clear whether ‘concurrent’ implies simultaneous decision making in the two jurisdictions.

2 Our citizens’ assembly was conducted in March 2019, at a time when the Northern Ireland Assembly had been collapsed for over two years. It was finally restored in January 2020.

3 One of the authors, John Garry, served on the Expert Advisory Group of the Irish Citizens’ Assembly 2016–18. For the methodological logic of the Irish Citizens’ Assembly see Suiter and Farrell (Citation2019) and Farrell, Suiter, and Harris (Citation2019). For an overview of the core features of citizens’ assemblies and the international experience see Farrell and Curato (Citation2019). Specifically, on the Northern Ireland experience of using deliberative fora see, for example, Garry, McNicholl, O’Leary, and Pow (Citation2018) and for their potential use and acceptability see Garry (Citation2016).

4 This date was originally chosen for its symbolic significance, being the day after the planned UK exit from the EU on March 29.

5 See supplemental data for the PowerPoint slides of Professor O’Leary’s presentation in the morning, Professor O’Leary’s presentation in the afternoon, as well as Professor Garry’s opening remarks.

6 See supplemental data for the moderators’ guide for the morning session and also the afternoon session.

7 The citizens’ assembly was very similar to other citizens’ assemblies, the main difference being that it was single day, though note that the exercise of Fishkin et al was also a single day (Citation2012).

8 It is worth noting that previous attempts at deliberating on highly sensitive topics in Northern Ireland and elsewhere proved successful in the sense that courteous deliberation occurred (Garry et al., Citation2018; Fishkin, Luskin, O'Flynn, & Russell, Citation2012). The same was possible in deliberating on sensitive issues in the Republic of Ireland (Farrell, Harris, & Suiter, Citation2017 and Farrell et al., Citation2019), and in the UK on the divisive issue of the UK’s exit from the EU (Renwick et al., Citation2018).

9 See supplemental data.

10 See supplemental data.

References

- Aughey, A. (2005). The politics of Northern Ireland: Beyond the Belfast agreement. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bächtiger, A., Dryzek, J., Mansbridge, J., & Warren, M. (Eds.). (2018). The Oxford handbook of deliberative democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Coakley, J. (2014). British Irish institutional structures: Towards a new relationship. Irish Political Studies, 29(1), 76–97. doi: 10.1080/07907184.2013.874999

- Coakley, J. (2017a). Adjusting to partition: From irredentism to ‘consent’ in twentieth-century Ireland. Irish Studies Review, 25(2), 193–214. doi: 10.1080/09670882.2017.1286079

- Coakley, J. (2017b). Resolving international border disputes: The Irish experience. Cooperation and Conflict, 52(3), 377–398. doi: 10.1177/0010836716684881

- Farrell, D., & Curato, N. (2019). Deliberative mini-publics: Core design features. Working Paper of the Centre for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance, Canberra (pp. 1–12).

- Farrell, D., Harris, C., & Suiter, J. (2017). Bringing people into the heart of constitutional design: The Irish constitutional convention of 2012–14. In X. Contiades, & A. Fotiadou (Eds.), Participatory constitutional change: The people as amenders of the constitution (pp. 120–135). London: Routledge.

- Farrell, D., Suiter, J., & Harris, C. (2019). Systematising constitutional deliberation: The 2016–18 citizens’ assembly in Ireland. Irish Political Studies, 34(1), 113–123. doi: 10.1080/07907184.2018.1534832

- Fishkin, J. (2009). When the people speak: Deliberative democracy and public consultation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fishkin, J. S., Luskin, R. C., O'Flynn, I., & Russell, D. (2012). Deliberating across deep divides. Political Studies, 62(1), 116–135.

- Garry, J. (2016). Deliberative democracy in Northern Ireland. Knowledge Exchange Seminar Series, Northern Ireland Assembly.

- Garry, J., McNicholl, K., O’Leary, B., & Pow, J. (2018). Northern Ireland the UK’s exit From the EU: What do people think? London: UK in a Changing Europe.

- Gibbons, I. (2018). Drawing the line: The Irish border in British politics. London: Haus.

- Humphreys, R. (2018). Beyond the border: The Good Friday Agreement and Irish unity After Brexit. Dublin: Irish Academic Press.

- Maher, I. (2017). The common travel area: more than just travel. A Royal Irish Academy-British Academy Briefing Paper, October.

- McCrudden, C. (2017). The Good Friday Agreement, Brexit, and rights. A Royal Irish Academy-British Academy Briefing Paper, October.

- McGarry, J., & O’Leary, B. (1995). Explaining Northern Ireland: Broken images. Oxford: Blackwell.

- McKittrick, D. (2012). Making sense of the troubles: A history of the Northern Ireland conflict (rev. ed.). London: Viking.

- Meehan, E. (2014). The changing British–Irish relationship: The sovereignty dimension. Irish Political Studies, 29(1), 58–75. doi: 10.1080/07907184.2013.875002

- Ó Beacháin, D. (2019). From partition to Brexit: The Irish government and Northern Ireland. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- O’Leary, B. (2019a). A treatise on Northern Ireland: Vol. 1. Colonialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- O’Leary, B. (2019b). A treatise on Northern Ireland: Vol. 2. Control. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- O’Leary, B. (2019c). A treatise on Northern Ireland: Vol. 3. Consociation and confederation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- O'Malley, E., Suiter, J., & Farrell, D. M. (2019). Does talking matter? A quasi-experiment assessing the impact of deliberation and information on opinion change. International Political Science Review, 130(1), 7–27. doi: 10.1177/0192512107070398

- Renwick, A., Allan, S., Jennings, W., Mckee, R., Russell, M., & Smith, G. (2018). What kind of Brexit do voters want? Lessons from the citizens’ assembly on Brexit. Political Quarterly, 89(4), 649–658. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12523

- Ruane, J., & Todd, J. (1996). The dynamics of conflict in Northern Ireland: Power, conflict and emancipation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ruane, J., & Todd, J. (Eds.). (1999). After the Good Friday Agreement: Analysing political change in Northern Ireland. Dublin: University College Dublin Press.

- Ryan, B. (2001). The common travel area between Britain and Ireland. Modern Law Review, 64, 855–874. doi: 10.1111/1468-2230.00356

- Ryan, B. (2016). The implications of UK withdrawal for immigration policy and nationality law: Irish aspects [ ILPA Position Paper 8]. London: Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association.

- Suiter, J., & Farrell, D. (2019). Reimagining democracy: Lessons in deliberative democracy from the Irish front line. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Todd, J. (2017). Contested constitutionalism? Northern Ireland and the British-Irish relationship since 2010. Parliamentary Affairs, 70(2), 301–332.