ABSTRACT

Analysis of the flow of demographic trends and the evolution of political forces in Northern Ireland has long had a predominantly binary focus. The many studies of the fall and rise of nationalism, and of the rise and fall of unionism, are based on a sometimes explicit but more often unspoken narrative of competition between two communities. This article considers an issue in relation to which a much smaller literature has appeared: the steady growth of an apparent middle ground. This is made up in part of those who were born outside Northern Ireland. But it also includes people who have exited from affiliation to the two dominant communities defined by religious background, or perhaps never belonged to either; of those who do not see themselves unambiguously as British or as Irish, but rather report a dual or alternative identity; and of those who identify with neither the unionist nor the nationalist community. Using census and survey data, the article tracks the evolution of this expanding section of the population, and assesses its implications for political choice and for the future constitutional path of Northern Ireland.

Introduction

The string of impressive electoral successes notched up by the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland in 2019 was hailed as a mould-breaking development. The party almost doubled its support in the local elections, more than doubled its vote share in the European elections, saw the election of its leader to the European Parliament and won a record 17% of votes in the December 2019 House of Commons election. Not surprisingly, this outcome was dubbed ‘the rise of the centre ground’ (Hayward, Citation2020).

Did the election really reflect a fundamental reorientation of political ties in Northern Ireland, or might it have been simply a pragmatic response to traumatic political events, such as Brexit? This article explores the extent to which underlying value changes might constitute a basis for some form of electoral realignment. It begins by discussing certain general analytical issues, before going on to look at three domains that are of particular significance, though sometimes conflated: deconfessionalisation at the level of religion, disaffiliation at the level of national identity, and dealignment at the level of communal identification. It concludes by examining the political implications of change at these three levels.

Intermediate groups in divided societies

Attempts to devise institutional architecture that would transcend group boundaries in deeply divided societies have attracted mixed verdicts. Thus, while consociational settlements such as the Good Friday Agreement have been widely welcomed, they have also generated an extensive literature that is critical of their capacity to bridge the gap between communities in conflict (see, for example, Dixon, Citation2018; Taylor, Citation2006; Wilford, Citation2010; Wilson, Citation2009). It is also widely acknowledged that since by their very nature such settlements give privileged status to certain cultural segments (those between which power is formally shared), they necessarily, and ironically, undermine the status of others, resulting in an outcome that has been labelled ‘exclusion amid inclusion’ and is the subject of a growing literature (Agarin & McCulloch, Citation2020; Agarin, McCulloch, & Murtagh, Citation2018). It has also found its way into the legal literature in the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Stojanović, Citation2018).

Being bypassed in a peace settlement does not inevitably lead to political invisibility; there are types of consociational arrangements where such ‘other’ groups may acquire considerable political significance (Agarin, Citation2020, pp. 12–13). Notwithstanding dire predictions in the past about the long-term prospects for the Alliance Party in Northern Ireland, it, too, has been found ‘capable of playing an effective role’ in the political process even before its recent victories (Mitchell, Citation2018, pp. 343–344). Like the inclusive ‘civic’ parties in Bosnia and Hercegovina, which aspire to represent all significant social groups, it has displayed a capacity to ‘skilfully navigate the institutions’ (Murtagh, Citation2020, p. 87).

‘Others’ are not necessarily a numerically stable group. Their numbers may shrink or expand, and the boundaries that separate them from other groups may be complex, imprecise and ever-shifting. This is borne out in survey-based investigation, which has shown that different types of identity (such as national or religious) vary considerably in their importance for individuals, and change over time (Muldoon, McNamara, Devine, & Trew, Citation2008). This is compatible with conclusions based on qualitative research; one major study of this kind concluded that post-conflict identity change in the early twenty-first century had been ‘pervasive’ in Northern Ireland (Todd, Citation2018, p. 127), and a later local study confirmed that the intensity of intercommunal barriers had diminished (Dornschneider & Todd, Citation2020, p. 12).

The combination of fluid social boundaries with uneven access to state power in consociational settlements raises important questions about the relationship between excluded categories and the traditional blocs. How extensive is this ‘leakage’ from the traditional blocs, and what are its political consequences? These are big questions, of which this article tackles mainly the first, making some concluding remarks about the second.

Simply looking at the extent of ‘leakage’ raises important issues of definition – not least, the most obvious question: ‘leakage’ from what? Indeed, is the process even one of ‘leakage’, since changing ethnic demography may also be a consequence of migration? There are different ways of approaching the dual structure of the Northern Ireland population. Is the crucial difference one between Catholics and Protestants, where religious denominational adherence is the crucial line of division? Is it between those seeing themselves as predominantly Irish or British, reflecting long-standing loyalties that are based on a distinctive historical origin myth that is now articulated by reference to national identity? Or might it be between those who self-designate as ‘nationalist’ or ‘unionist’, labels that reflect contrasting perspectives on political life and constitute a form of communal alignment? The three sections that follow consider these dimensions in turn, each beginning with an overview of its socio-political significance, assessing the challenges in measuring it, analysing the extent to which change over time may be identified, and concluding with a discussion of the extent to which we may detect shifting relationships between established blocs and the emergence of a ‘middle ground’.

This article relies on three main sources: the decennial population census, supplemented by microdata from 2011 (a 5% anonymised sample); the little-used Continuous Household Survey, which has included a question on national identity since 2012–13; and the Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey (1998–2019). Use is also made of a number of other well-known surveys, notably the Northern Ireland Social Attitudes Survey (1989–1996).Footnote1 The number of cases in the Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey (in recent years, about 1,200) is relatively modest, so to permit analysis of smaller groups a pooled dataset spanning the years 2013–19 has been created. Combining data over so long a time span brings obvious dangers, but these diminish when the variables in question, such as religious affiliation, national identity and communal alignment, are relatively stable. In addition, with a view to countering sampling error when the number of cases is relatively small, spline curves rather than linear point-to-point connectors have been fitted to the linecharts below, and, apart from the first and the last datapoint for each line, three-year moving averages have been used. This has the effect of smoothing what would otherwise be excessively ‘spiky’ lines and reporting a more realistic representation of change.

Religion: the threat of deconfessionalisation?

The role of religion as a source of division in Northern Ireland is so well established as to require little further discussion. For some, it is the central, fundamentally divisive reality lying behind the conflict (for discussion, see Ganiel, Citation2016; Mitchell, Citation2006a, Citation2006b). More generally, though, it is a social phenomenon that defines communal identity by pointing towards ancestral bonds that link people to a perceived past, differentiating them from the rival community, whose collective narrative rests on a conflicting historical myth. To cite one classic and one contemporary view, a half century ago, Richard Rose (Citation1971, p. 184) argued that ‘Protestants have always assumed that there is a great gulf fixed between them and their Catholic neighbours’, while ‘Catholics have emphasised their alienness from those who consider themselves British’. Almost five decades later, the assessment of Brendan O’Leary (Citation2019, p. 11) was similar: reflecting on the ethnic origins of the conflict, he remarked that Northern Ireland's ‘two largest descent groups are religiously labelled’, with Catholics regarding themselves as ‘descendants of the native Irish, who preceded in residence the English and British conquerors of Ulster’, while Protestants ‘mostly regard themselves as the descendants of British settlers in Ireland’. The two communities were set apart not just by religion, but by language and culture, which separated largely Anglo-Scots Protestants from mainly Gaelic Irish Catholics (Coakley, Citation2011, p. 98). Interdenominational differences were hardened by being embedded in law, with a privileged Anglican (Church of Ireland) minority monopolising power, Presbyterians and other Protestants excluded, and the Catholic majority marginalised, lacking both political and civil rights. By the late nineteenth century, following mass mobilisation in the 1880s, it had become clear that electoral behaviour was overwhelmingly structured by religious affiliation, and that political preferences, including in particular attitudes towards the constitutional question of the Union, were similarly determined (Coakley, Citation2002).

Religion was not, however, a clear-cut dividing line. As in other post-industrial societies, the process of secularisation has created an increasing pool of non-religious or ‘independent’ persons who have moved out of the traditional religious blocs, raising the prospect of the emergence of a political middle ground, since there is a strong tendency for the denominationally ‘neutral’ to support parties of the centre (Hayes & McAllister, Citation1995). This trend was particularly noticeable among the religiously unaffiliated of Protestant background (Breen & Hayes, Citation1997).

Measuring religious affiliation has been relatively straightforward, since religion traditionally occupied a central state role and has had formal criteria of membership, such as overt patterns of worship and, in the Christian tradition, participation in such ceremonies as baptism and confirmation. The reliability of census data on religion since 1861 has thus been taken for granted, but difficulties began to emerge in 1971, when the proportion not answering this question rose sharply. In 2001 a new approach was adopted, following what was by then established practice in survey research. Those not indicating their religion, or saying they had none, were asked a supplementary question about childhood religion, to produce a new variable, ‘community background (religion or religion brought up in)’ (NISRA, Citation2013). It should be stressed that in this article, except where otherwise indicated, ‘religion’ refers to religion currently practiced, not to background.

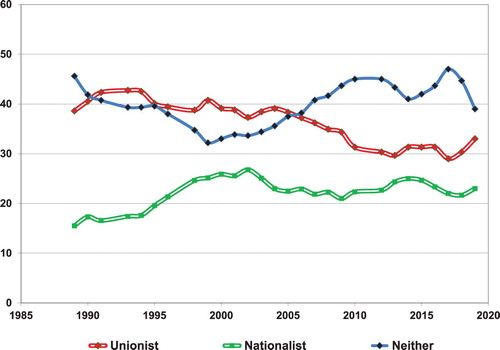

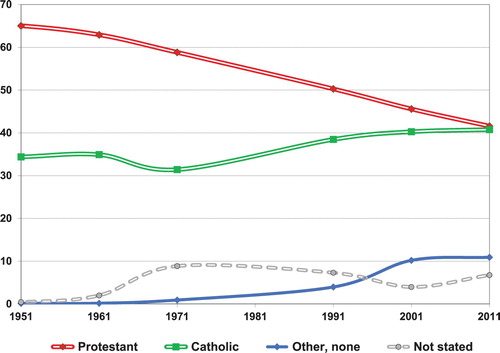

The changing religious denominational face of Northern Ireland is summarised in . This traces the evolution of four groups since 1951, a year in which the census recorded essentially the same denominational balance as had been the case since 1901 in the six counties that would constitute Northern Ireland after partition: (1) Protestants (including all other Christians), (2) Catholics, (3) those subscribing to other religions or to none, and (4) those not reporting their religion. The most striking trend is a sharp, linear decline in the proportion of Protestants (from 65% in 1951 to 42% in 2011), matched by a less steep rise in the proportion of Catholics (from 34% to 41%), with the dip in 1971 attributable to disproportionate refusal to answer the religion question. ‘Other’ religions have too few adherents to show on this graph; they would be indistinguishable from the horizontal axis, since they increased from only 0.1% in 1951 to 0.8% in 2011. The two remaining lines on the graph refer to those with no religion (not recorded in 1951; 10% in 2011) and those not stating their religion (increasing from 0.4% to 7% over the same period).

Figure 1. Religious affiliation, 1951–2011 (percent).

Note: Data for 1981 omitted due to under-enumeration and incomplete response. ‘Protestant’ includes all other Christian denominations.Source: Census of Northern Ireland, 1951–2011, available www.nisra.gov.uk. Data for 1971 replaced by estimates from Compton (Citation1985, p. 207). Data for ‘other, none’ and ‘not stated’ in 2001 recomputed on the basis of information in NISRA (Citation2013, pp. 3–5).

For purposes of this article, the most important question has to do with those falling outside the two major denominational blocs. As shows, those classified as belonging to other (non-Christian) religions were originally made up overwhelmingly of the Jewish population, which accounted for 74% of all non-Christian denominations in 1951. But by 2011 the Jewish share had dwindled to just 2% of ‘others’, a category now dominated by newer arrivals (Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists and others) of whom 53% were born outside Northern Ireland. But the number of adherents of non-Christian religions remains small: just under 15,000 in 2011.

Table 1. Non-Christian religions, 1951–2011 (percent).

Those professing no religion were a much bigger category in 2011, reaching 10% of the population. A little over three quarters had been born within Northern Ireland; those born elsewhere (23%) accounted for a disproportionately large share (11% of the overall population were born outside Northern Ireland; NISRA, Citation2020, table DC2241NI). Most of those returned as having no religion were themselves of a non-religious background (52%); 34% had been brought up as Protestants and 13% as Catholics.Footnote2 But those who continued to identify with a particular religious denomination were not necessarily themselves regular church attenders. Survey data over the seven-year period 2013–19 suggest that only 27% of Protestants and 33% of Catholics attend church at least once weekly.Footnote3

A number of important conclusions may be drawn about patterns of religious affiliation in Northern Ireland, and in particular about patterns of withdrawal from this. First, notwithstanding the strength of denominational affiliation and the powerful bonds on which it is based (including public religious rituals, denominational schooling, a centuries-old tradition of official counting of people according to denominational labels, and more recent determined attempts to assign people to one or other of the two main denominational groups for employment monitoring purposes), there has been a steady, if recent, process of ‘leakage’ from the traditional churches towards an agnostic position: by 2011, as noted above, those claiming not to adhere to any denomination accounted for 10% of the population. Second, among adherents of the traditional churches there has been an apparent decline in intensity of commitment: in addition to evidence of falling levels of adherence to traditional religious norms, data from the NILT pooled dataset 2013–19 show the proportion of weekly churchgoers dropping steadily by age group, from 45% among those aged over 65 to 15% among the 18–24 group. Third, there has been some dilution in the composition of the two main groups: once recruited overwhelmingly from the local population, 11% of Catholics and 7% of Protestants had been born outside Northern Ireland by 2011.

National identity: the challenge of disaffiliation?

Religious and political positions were once closely aligned; the boundary commission of 1925, for example, charged with redefining the line of the Irish border, concluded after consulting a mass of evidence that there was no need for a plebiscite to establish people's wishes since these could be inferred from their religious affiliation (Coakley, Citation2016, p. 40). But the landmark pre-’troubles’ survey mentioned above suggested that by 1968 the implications of religious affiliation for national identity had become complex: a majority of Catholics described themselves as Irish, while a big majority of Protestants opted for the ‘British’ or ‘Ulster’ labels (Rose, Citation1971, pp. 207–209). By the close of the 1970s the polarisation in national identity was more pronounced, with Protestants largely abandoning the ‘Ulster’ label and instead describing themselves as ‘British’ (Moxon-Browne, Citation1983, p. 6). When a new option, ‘Northern Irish’, was introduced in 1986 a significant movement towards this category took place, apparently at the expense of the ‘Ulster’ category, and this was confirmed in a new survey in 1989 (Moxon-Browne, Citation1991). A continuous data series from then onwards suggests a consolidation in this position, with the ‘Ulster’ label shrinking to the point of disappearance and increased support for the ‘Northern Irish’ one.

The potential importance of the emergence of this new identity has been linked to its capacity ‘to bridge bipolar ethnic differentiation’ (McAuley & Tonge, Citation2010, p. 276) and to promote more moderate political attitudes (McNicholl, Citation2019, p. 44).Footnote4 It appears to have different significance for Catholics and Protestants, with the former initially more likely to adopt this label, but with Protestants taking the lead after 2006 (Tonge & Gomez, Citation2015, p. 294). This shift could be seen as a repackaging of old loyalties rather than marking the emergence of a centrist identity (Hayes & McAllister, Citation2009, pp. 390–392, 400).

Perhaps more striking than the degree of movement towards this new label is the resilience of the old ones. Hayes and McAllister (Citation2009, p. 392) note that ‘national identity remains strongly differentiated by religious denomination’; Muldoon, Trew, Todd, Rougier, and McLaughlin (Citation2007, p. 101) see forms of national identity as ‘constructed as oppositional and negatively interdependent’; and Tonge and Gomez (Citation2015, p. 295) argue that bipolar national identity forms part of ‘a deep political and cultural faultline’. Three factors help to explain this survival of the older labels. First, the Good Friday Agreement formally defined the polity as a dual one, solemnly recognising people's right ‘to identify themselves and be accepted as Irish or British, or both’ and to freely choose British or Irish citizenship, or both (McAuley & Tonge, Citation2010, p. 267). Second, powerful political forces reinforce the binary nature of identity. Unionist elites stress Britishness, not Northern Ireland identity; and their Sinn Féin counterparts are reluctant even to utter the name ‘Northern Ireland’, emphasising instead the ‘Irish’ dimension (Tonge & Gomez, Citation2015, pp. 279–80, 294). Third, identity labels may easily be confused with citizenship, and with overt ties that may have implications for identity, such as passport holding (Muldoon et al., Citation2007, p. 100).

There is no agreement on a single approach to the measurement of national identity (Coakley, Citation2007, pp. 581–587). The most commonly used instruments in Northern Ireland and in this article are survey questions in the following format:

single categorical choice: ‘which of the following best describes the way you think of yourself?’, as used in survey research since 1968, with minor variations in question wording;

multiple categorical choice, similar to the first approach, but where the respondent may select several options, with two variants:

a generalised query about personal identity (with wording similar to that above), as in most surveys;

a specific question: ‘how would you describe your national identity?’, as in the 2011 census, the continuous household survey and certain opinion polls;

bipolar ordinal scale, often called the ‘Moreno scale’: the two poles are defined as ‘British only’ and ‘Irish only’, with ‘more British than Irish’, ‘equally British and Irish’ and ‘more Irish than British’ as intermediate categories, often asked in surveys.

The options on offer of course also influence responses. We do not know how ‘Northern Irish’ might have fared in 1968, since it was not an option. The impact of the menu of options is obvious in the many surveys which have used both the first and third of the approaches above: British–Irish polarisation is much higher when a bipolar ordinal scale is applied than when there is a wider categorical choice menu.Footnote5

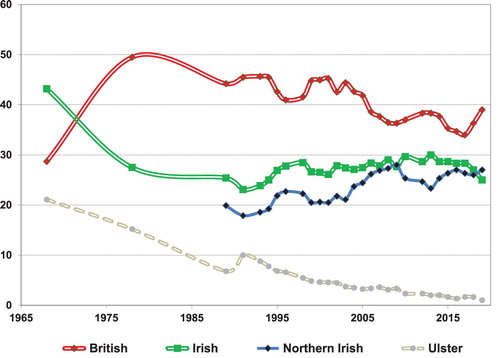

A general indication of the interplay between the several national identity labels, as measured using the first approach described above, is given in for the period 1968–2019. Striking trends for the early period include a sharp decline in Ulster and in Irish identity, in favour of British identity. This appears to have reflected a sharp drop in Irish identity among Protestants, of whom 20% described themselves as Irish in 1968, but only 8% in 1978 and 4% in 1989. Ulster identification similarly declined, especially after the introduction of a new ‘Northern Irish’ label in 1989. Over the later period (1989–2019), there have been three clear trends, each reflecting a process of very gradual change: a small rise in the ‘Northern Irish’ group (from 20% to 27%); relative stability in the proportion identifying as ‘Irish’ (starting and finishing at 25%, though reaching almost 30% in the intermediate years); and a rather more significant drop in those identifying as ‘British’ (from 44% to 39%, following a prolonged dip to the mid-30s from 2007 onwards).

Figure 2. National identity, 1968–2019 (percent).

Source: Loyalty survey, 1968; Northern Ireland Attitudes survey, 1978; Northern Ireland Social Attitudes Surveys, 1989–96; NILT surveys, 1998–2019. See note 1.

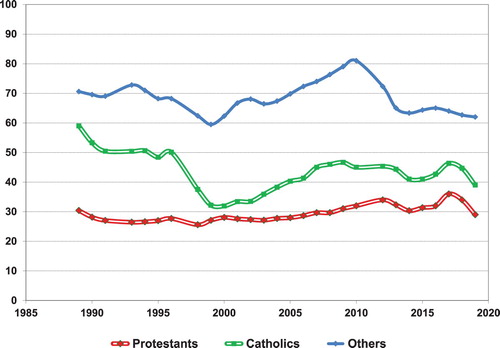

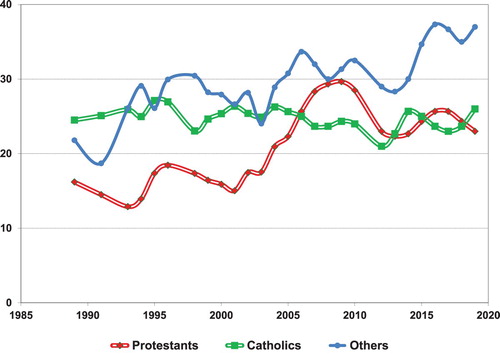

The long-term trend in ‘Northern Irish’ identity appears, then, not to reflect fully the assessments and predictions that have been offered about its political significance in undermining the British–Irish binary alternatives. To start with, the cross-over in Catholic and Protestant attitudes towards Northern Irish identity in 2006 (when this became more strongly associated with Protestants) appears not to have survived: by 2012 a new pattern had emerged, with Protestants no longer disproportionately gravitating towards this label. Since then, both have hovered around the 24% level. This may be seen in , which looks at the profile of Northern Irish identifiers since 1989, grouping them by denominational background. Over this entire period, Catholic ‘Northern Irish’ remained relatively stable, in the mid-20s. Protestant ‘Northern Irish’ increased from around 15% in the early 1990s to double this level but thereafter fell back, ultimately to the same level as Catholics. Support from those who were neither Catholic nor Protestant also increased steadily, reaching a plateau in the mid-30s in 2015.

Figure 3. ‘Northern Irish’ identity by religion, 1989–2019 (percent).

Source: Northern Ireland Social Attitudes surveys, 1989–1996; NILT surveys, 1998–2019. See note 1.

The relationship between Northern Irish identity, religion and age is intriguing. A persuasive argument has been made that the ‘Northern Irish’ label has been particularly attractive to young Protestants as a replacement for their traditional identity, with young Catholics tending instead to opt disproportionately for the ‘Irish’ label (Hayes & McAllister, Citation2009, p. 392). This is explored further in , which brings together three major data collections. The left-hand part of the table reports the extent to which three religious categories accepted the ‘Northern Irish’ label, whether as their only designation (top panel, ‘exclusive’), as one of possibly several designations (middle panel, ‘inclusive’) or as a single designation selected from a short list (bottom panel, ‘categorical’). Respondents were divided into three age groups and, to give an indication of the impact of age, the percentage in the oldest group was subtracted from the percentage in the youngest group. Thus, for example, 28% of Catholics aged under 35 identified exclusively as Northern Irish in 2011, as did a rather higher proportion (37%) of Catholics aged over 54; subtracting the latter figure from the former gives us a negative value, −9%, as reported in the top cell of the relevant column.Footnote6

Table 2. Three measures of ‘Northern Irish’ identity, 2011–19 (per cent).

A number of strong conclusions (reinforced by the large numbers of cases and the consistency of the patterns) emerge from . First, Catholics are more likely than Protestants to opt for an exclusive Northern Irish identity, as the middle left-hand panel of the table shows: in 2011, 28% of Catholics, but only 14% of Protestants, described themselves as ‘Northern Irish’ only, though the gap narrowed a little in subsequent years. Second, when respondents reported additional identities, Protestants overtook Catholics after 2011 (top panel), since many adopted dual or multiple identities (thus, a further 11% of Protestants identified as both Northern Irish and British; only 1% of Catholics did so, with a further 2% identifying as Northern Irish and Irish). Third, when forced to choose just one identity (importantly, labelled as ‘the way you think of yourself’ rather than as ‘your identity’), there were few differences between Catholics and Protestants, with about a quarter of each opting for ‘Northern Irish’ (bottom panel). Fourth, age clearly matters, and there are big differences between Catholics and Protestants in this respect: almost all of the figures in the ‘Catholic’ column on the right-hand side of are negative, indicating that older people are more likely to opt for ‘Northern Irish’ than younger people; but in the ‘Protestant’ column all of the figures are positive, indicating that younger people are more likely to favour ‘Northern Irish’. Finally, those of other religions, or none, are a little more likely than the average respondent to opt for ‘Northern Irish’, especially among the young, though the pattern here is less definite.

Content analysis of the use of identity labels in Northern Ireland Assembly debates (1998–2015) came to the surprising conclusion that the expression ‘Northern Irish’ was hardly ever used, even by the main advocates of an overarching identity, Alliance Party members. When used, it appeared to function in four different ways: to refer to a people, a place, an identity claim and a political project (McNicholl, Citation2018, pp. 502–503). Interviews with members of the Assembly and engagement with undergraduate focus groups confirmed the value of this four-fold framework in classifying feelings of identity (McNicholl, Stevenson, & Garry, Citation2019). This framework throws useful light on some of the variation in patterns of acceptance of the ‘Northern Irish’ label discussed above. A question about ‘how you think of yourself’ is sufficiently vague and general to refer to either a people or a place. It may offer a convenient way of sidestepping more fundamental questions about national belonging, especially among Catholics (see Todd, O’Keefe, Rougier, & CañásBottos, Citation2006, p. 334). A question that asks specifically ‘how would you describe your national identity?’ appears to fit comfortably into the ‘political project’ one, which seeks to develop a fresh identity marked by new symbols (a project, incidentally, likely to be viewed more negatively by Catholics or nationalists as one which legitimises Northern Ireland's distinct status). It also buys into a vocabulary more likely to be acceptable or even attractive to Catholics; Protestants typically fail to see unionism as a form of nationalism, tending to label its ideology as anti-nationalist, and stressing Northern Ireland's identity as shared with the British rather than marking out a distinct community.

The large datasets explored in this section offer some support for established findings about Northern Irish identity, but also suggest the need for qualification. Researchers in the early years of the twenty-first century have noted the strength of this identity among Protestants (especially younger ones), and this is borne out by the data presented here. But its relative strength among Catholics (especially older ones) is a more novel finding. Different approaches to measurement and variations in question wording may account for part of this; but deeper political cultural differences between groups may well be the hidden explanation. The findings of Richard Rose (Citation1971, p. 209) retain much of their validity: those who opted for ‘Irish’ or ‘Ulster’ identity in his survey gave as their reason the fact that they were ‘born and bred’ into it (93% and 81% respectively), whereas most of those selecting ‘British’ (53%) gave as their reason the fact that they were ‘under British rule’.

Communal identification: the prospect of dealignment?

The two features discussed so far – religion and national identity – have deep roots, and are common lines of social division in other states. It is well known that religious affiliation structured political status on the island of Ireland for centuries. But national identity was always a more elusive term. The noun ‘United Kingdom’ has no adjectival form, so the population of the state after the Union of 1801 was described as ‘British’ (with English, Scottish and Welsh components) and ‘Irish’ (a designation with implications that appear to have been a little stronger than mere geographical ones). With mass political mobilisation in the late nineteenth century, the terms ‘Ulster’ and ‘Gaelic’ began to challenge the more inclusive ‘Irish’ label, while ‘Anglo-Irish’ emerged to describe a group defined both by religion and class.Footnote7 With the transformation of the United Kingdom after the secession of the Irish Free State in 1922, nomenclature became more challenging, with ‘Northern Irish’ emerging as a geographical label; later, alongside ‘Ulster’, it was adopted by some as a communal descriptor.

With the end of the old Stormont system in 1972, Northern Ireland was increasingly referred to as a ‘bicommunal’ society. Initially, the communities were not named, though the qualifiers ‘Catholic-Protestant’, ‘Nationalist-Unionist’ and ‘Majority-Minority’ were often used. Consociational arrangements, however, require a precise designation of the groups between which power is to be shared, and there were difficulties in labelling these. By the early 1980s, the terms ‘nationalist community’ and ‘unionist community’ had become part of the political vocabulary, alongside the expressions ‘two identities’ (as in the 1982 British proposals to restore devolution) and ‘two traditions’ (as in the 1985 Anglo-Irish agreement). All three of these nouns (community, identity and tradition) found their way into the Good Friday Agreement (1998), which has been described as resting on ‘a narrative of two fundamentally distinct communities’ or ‘traditions’, rather than mere ideologies or political preferences (Hayward & McManus, Citation2019, p. 140). The agreement added a fourth noun, ‘designation’, and gave this legal significance, since all members of the Assembly are required to choose between three designations: ‘nationalist’, ‘unionist’ and ‘other’.

These designations are of legal as well as sociological significance: they matter in certain key decisions, such as selection of First Minister and Deputy First Minister and specific items of Assembly business. The Good Friday Agreement thus potentially undermined the status of the political centre, and on occasion incentivised the non-aligned to switch to the unionist or nationalist designations (Evans & Tonge, Citation2003, p. 48).Footnote8 This went far in the direction of formal recognition of separate communities, but stopped well short of the ultimate codification of division: the use of such devices as separate electoral rolls or population registers for the co-existing communities.

Keeping pace with these developments, the dual character of Northern Ireland has been probed since 1989 by means of a new survey question: ‘generally speaking, do you think of yourself as a unionist, a nationalist or neither?’ Responses to this have consistently shown a near-universal reluctance of Catholics to self-identify as unionist, and of Protestants to self-identify as nationalist, though many opt out and declare themselves to be ‘neither’. The group seeing themselves as neither unionist nor nationalist quickly came to overshadow those adopting the other two labels; its members were likely to be

young, female, of both British and Irish identity, to have lived outside Northern Ireland, to have some [educational] qualification (especially at the highest levels), to have gone to a mixed school, to be in paid employment and to have a high income. (Hayward & McManus, Citation2019, p. 153)

An outline of the evolution of responses to the question on communal alignment over the period 1989–2019 is provided in . This shows a steady decline in unionist identity, from a little more than 40% in the early 1990s to 33% in 2019. Those identifying as nationalist, in the high teens in the early 1980s, rose to the mid-20s in the twenty-first century, and registered 23% in 2019. Perhaps surprisingly, those identifying as neither unionist nor nationalist declined until the end of the last century, but gradually increased thereafter, from 30% in 1998 to around the mid-40s in the 2010s. A sharp dip in 2019 may be an indication of change, but it is too early to say whether this is a ‘blip’ or evidence of longer-term shift (Hayward & Rosher, Citation2020, p. 2).

A breakdown by religion of those opting for the ‘neither’ category over the period 1989–2019 is summarised in . This shows Protestants as consistently the least likely to select the ‘neither’ label: for years, just under 30% of Protestants were recorded as ‘neither’, though this figure rose incrementally after 2009, before dropping sharply again after 2017. Support among Catholics was initially much higher, at 59% in 1989; but it dropped after this, first steadily, then precipitously, so that in the years of and immediately after the Good Friday Agreement it was in the low 30s. It rose steadily thereafter, to reach the mid-40s after 2007, but dropped to 39% in 2019. Those belonging to other religions or to none were strongest of all in their support of the ‘neither’ option, dropping from 71% in 1989 to 62% in 2019, but with a trough at the time of the Good Friday Agreement and a peak of over 80% in 2009–2010.

The ‘unionist’ and ‘nationalist’ labels have inescapable political implications. As popularised in Ireland in the late nineteenth century, they referred not so much to two communities as to two political positions in respect of the British–Irish Union of 1801, and these were expressed in support for two distinct political parties and for two diametrically opposed constitutional priorities – and ultimately they were reflected in clashing patterns of national identity. To what extent do these communal labels continue to have broader political implications? summarises the position in 2019, which reflects a pattern that remained stable over many years.

Table 3. Communal alignment by national identity, party bloc support and constitutional preference, 2019.

As the top panel shows, there is a very strong association between communal affiliation and national identity: 83% of unionists see themselves as British, and almost all of the remainder (16%) as Northern Irish; 76% of nationalists see themselves as Irish, and almost all of the remainder (23%) as Northern Irish; while a plurality of those who do not identify as either unionist or nationalist identify as Northern Irish (46%), with the remainder divided between British and Irish.

The middle panel shows a very strong relationship with party support: unionists vote overwhelmingly for parties in the unionist bloc, as do nationalists (if slightly less overwhelmingly) for parties in the nationalist bloc. To the extent that there is ‘leakage’, this percolates no further than parties of the centre; it does not translate into even minuscule support for parties of the rival bloc. The large segment who describe themselves as neither unionist nor nationalist opt overwhelmingly for parties of the centre, of which the Alliance Party is most significant.

As the bottom panel shows, unionists, not surprisingly, opt almost exclusively for the Union (96%), as do a big majority of the ‘neither’ group. But the position is not symmetrical: although most nationalists support Irish unity (76%), a sizeable minority do not: 20% support the Union, notwithstanding their ‘nationalist’ self-designation.

As this section has shown, there has been an apparently sizeable migration out of the traditional unionist and nationalist designations in Northern Ireland. We do not have precise data on the extent to which these labels were generally shared before the era of public opinion surveys, but by the end of the twentieth century a very large group – ultimately, larger than either the unionist or nationalist groups – defined itself as associated with neither designation. There is evidence that members of this group have broken with communal electoral loyalties (with a majority supporting parties of the centre), but it remains divided between supporters and opponents of the Union.

An emerging middle ground?

This article has sought to examine the extent to which shifting value patterns in Northern Ireland may have placed traditional loyalties under strain and opened the way for new political alignments, in particular by preparing the ground for a reinforcement of the political centre. How may we generalise about these patterns, and what are their political implications?

It is clear that not all change is domestically generated. Immigration has played a significant role, though its extent should not be exaggerated. The 11% reported in the 2011 census as having been born outside Northern Ireland came mainly from familiar adjacent territories: it was made up of 5% born in Great Britain, 2% in the Republic and 4% elsewhere. In respect of religion, these groups reflected their geographical origins: 64% of those born in the Republic were Catholic, 38% of those born in Great Britain were Protestant (with 29% Catholic and 28% other or no religion), and of those born elsewhere 44% were Catholic and 28% other or none, with the Catholic share boosted by the large number of Polish and Lithuanian immigrants. In respect of national identity, these three groups remained even closer to their origins, with 78% of those born in the Republic identifying as Irish, 61% of those born in Great Britain as British, and 67% of those born elsewhere as nationals of other states.

The net effect of immigration appears, then, to be a small boost to the proportion of Catholics and of those with no religion, and slight downward pressure on the proportion opting for ‘Northern Irish’ identity (NISRA, Citation2020). Survey data from 2016, however, show that when it comes to communal alignment those born elsewhere opt out of the unionist – nationalist dichotomy: 52% of those born in the Republic, 60% of those born in Great Britain and 79% of those born elsewhere indicated that they felt neither unionist nor nationalist, though 73% of those born in the Republic supported one of the two main nationalist parties. Strikingly, 36% of those born in Great Britain and 40% of those born elsewhere supported the political centre, figures well above that for those born in Northern Ireland (18%).Footnote9

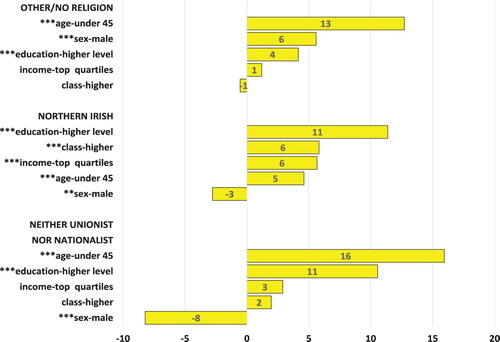

A full analysis of the characteristics of those who fell outside the binary categories discussed here would go beyond the scope of this article, but explores the importance of five dichotomised socio-demographic features for the respective dimensions (religious affiliation, national identity and communal alignment). The bars report the difference between two values in each case: the percentage associated with the reference value and the percentage not so associated. Thus, for example, the top bar reports the difference between the percentage of those aged under 45 who belonged to a non-Christian religious group, or to none (26%) and the percentage of those aged 45 or over who belonged to the same group (13%), a difference of 13%. Two variables have a strong impact – age and education, with those under 45 and those with relatively high education levels less likely to belong to one or other side in the main binary division. Those with higher incomes and from higher socio-economic groups are more likely to adopt a Northern Irish identity, but these variables have little impact on the other two dimensions. The effect of sex is surprising: men are more likely to be non-religious, but sex makes little difference as regards Northern Irish identity, and it is women rather than men who are more likely to opt out of the unionist-nationalist classification.

Figure 6. Background features of those associated with ‘middle’ positions, 2013–19.

Note. Bars refer to the difference between the named feature and its alternative (percentage sharing the named characteristic minus percentage not sharing it). **p<.01 ***p<.001, based on chi-square tests. Source: NILT pooled dataset, 2013–19.

These changes acquire particular meaning in the context of electoral behaviour in Northern Ireland. The post-Brexit period witnessed an upsurge in the popularity of parties outside the two main blocs; they were supported by 25% over the four Life and Times surveys, 2016–2019. But support for these parties was even stronger among those reporting a Northern Irish identity (38%), who were neither unionist nor nationalist (51%), and who did not belong to either of the two main religious blocs (53%). When the cumulative impact of these variables is examined, the outcome is even more striking: of those who did not belong to either religious bloc and who also opted out of the ‘unionist-nationalist’ classification, 70% supported the political parties of the centre.

Conclusion

The evidence explored in this article, then, suggests that a new middle ground is indeed slowly emerging in Northern Ireland. The combined forces of immigration and domestic value shift seem calculated to promote an adjustment in traditional patterns of voting behaviour, reflected not just in changing party loyalties but also, no doubt, in the increased likelihood of lower preference votes transferring towards the centre. A small but growing share of the population no longer classifies itself as Protestant or Catholic, and it is sufficiently large to soften the impact of demographic competition as the two traditional denominational blocs approach parity. An emerging ‘Northern Irish’ identity, particularly pronounced among young Protestants, appears to point towards a modest flight from the British–Irish dualism that has marked the Northern Ireland conflict, though its trajectory is an uncertain one. The spectacular growth of a section of the population that rejects the ‘unionist’ and ‘nationalist’ labels – and that, indeed, now eclipses them – points towards a melting of that very political segmentation that laid the ground for Northern Ireland's consociational arrangements.

The terminology used here, which includes repeated references to the political ‘centre’ and the ‘middle’ ground, raises a key question. Is there indeed something ‘centrist’ about the nature of emerging social and political forces, with implications of compromise, moderation and neutrality? The answer seems to be that there may be, but not necessarily. It is possible to measure fervour of religious commitment by using a scale (such as one based on frequency of church attendance, or on degree of religiosity); to measure intensity of national identity by using a similar scale (a five-point ‘Moreno’ scale is the most obvious); and to measure depth of unionist commitment by using a similar well-established scale.Footnote10

However, the Northern Ireland case illustrates clearly that, while the three dimensions considered in this article may indeed be visualised and measured as if each was a continuum (such as religious Protestant to non-believer, strong British identity to purportedly no national identity, strong unionist alignment to none), there is an important sense in which different positions may be seen as unconnected categories rather than as points on a scale. Opting out of Protestantism, in other words, may mean moving to a radically secular, non-religious position such as atheism; but it may also mean joining another religion, such as Islam. Abandoning British identity may mean moving in the direction of Irish identity; but it may entail selecting an altogether different identity, such as Ulster or Northern Irish. Detaching oneself from unionist alignment may imply embracing a ‘centrist’ stance; but it may also mean adopting a radical loyalist position (such as one associated with the notion of an independent Northern Ireland).

From the perspective of Northern Ireland's bipolar politics, it may indeed matter whether the ultimate destination of new entrants to the political community, or switchers within it, is an intermediate point on a scale or a new category. But what matters more is the progressive weakening of the traditional polar positions of the kind documented in this article. It is likely, then, that the electoral success of the Alliance Party and the political centre in its record-breaking year of 2019 is no flash in the pan but rather points to slow, long-term political realignment.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank ARK – The Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey, the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency and the UK Data Archive for making available the data on which this article is based. I am indebted to Kevin McNicholl and the anonymous referees for perceptive comments on an earlier draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

John Coakley

John Coakley, MRIA, is a professor in the School of History, Anthropology, Philosophy and Politics at Queen's University Belfast and a fellow in the Geary Institute for Public Policy at University College Dublin. His research interests include nationalism, ethnic conflict, and Irish and Northern Irish politics.

Notes

1 The following are the main datasets used: Northern Ireland Loyalty Survey, 1968 (ICPSR, study no. 7237); Northern Ireland Attitudes Survey, 1978 (UK Data Archive, study no. 1347); Northern Ireland Social Attitudes surveys, annually, 1989–91, 1993–96 (UK Data Archive, study nos. 2792, 2841, 2953, 3440, 3590, 3797, 4130); Northern Ireland Life and Times surveys, annually, 1998–2010, 2012–9 (available ARK – Northern Ireland Social and Political Archive: www.ark.ac.uk/nilt); Northern Ireland Census 2011 anonymised 5% sample, regional dataset (UK Data Archive study no. 7769); Power-Sharing and Voting: Conflict, Accountability and Electoral Behaviour at the 2016 Northern Ireland Assembly Election (UK Data Archive study no. 8293); and Northern Ireland Continuous Household Survey 2012–13 to 2017–18 (UK Data Archive study nos. 7564, 7906, 8083, 8410, 8411 and 8585).

2 Based on re-analysis of Census 2011 5% sample (see note 1).

3 NILT pooled dataset, 2013–19 (see note 1).

4 This was based on a very large dataset (comprising 11,097 respondents in Ipsos-MORI surveys in 2014–16), which tracked the emergence of the ‘Northern Irish’ category in detail (McNicholl, Citation2019).

5 Evans and Tonge (Citation2003) offered another intermediate category in their survey of Alliance Party members: ‘British-Irish’—a popular option that implied a more inclusive self-identification as both British and Irish (whereas ‘Northern Irish’ implies an opting out of this binary relationship).

6 The data presented in the top panel match closely the pooled survey data analysed by McNicholl (Citation2019, p. 34), which used the same measurement device as the census.

7 Playwright Brendan Behan famously summarised the class dimension in his play The Hostage (1958) by describing an Anglo-Irishman as ‘a Protestant with a horse’.

8 For example, when David Trimble sought re-election as First Minister following a tactical resignation, there was insufficient support for the prescribed ‘parallel consent’ (which required not just an overall majority in the Assembly, but also support from a majority of nationalist- and unionist-designated members). It was only after one Women's Coalition and three Alliance MLAs redesignated as ‘unionist’ that Trimble had sufficient votes for re-election, on 6 November 2001.

9 Computed from the dataset ‘Power-Sharing and Voting’; see note 1.

10 Scales of this kind are common in Northern Ireland survey research. For example, the NILT series uses an eight-point scale of church attendance, running from ‘several times a week’ to ‘never’. It also uses a five-point ‘Moreno’ scale as described earlier, running from ‘Irish not British’ to ‘British not Irish’. Combining two other questions generates a seven-point unionist-nationalist scale running from ‘very strong unionist’ to ‘very strong nationalist’.

References

- Agarin, T. (2020). The limits of inclusion: Representation of minority and non-dominant communities in consociational and liberal democracies. International Political Science Review, 41(1), 15–29.

- Agarin, T., & McCulloch, A. (2020). How power-sharing includes and excludes non-dominant minorities: Introduction to the special issue. International Political Science Review, 41(1), 3–14.

- Agarin, T., McCulloch, A., & Murtagh, C. (2018). Others in deeply divided societies: A research agenda. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 24(3), 299–310.

- Breen, R., & Hayes, B. C. (1997). Religious mobility and party support in Northern Ireland. European Sociological Review, 13(3), 225–239.

- Coakley, J. (2002). Religion, national identity and political change in modern Ireland. Irish Political Studies, 17(1), 4–28.

- Coakley, J. (2007). National identity in Northern Ireland: Stability or change? Nations and Nationalism, 13(4), 573–597.

- Coakley, J. (2011). The religious roots of Irish nationalism. Social Compass, 58(1), 95–114.

- Coakley, J. (2016). Does Ulster still say no? Public opinion and the future of Northern Ireland. In J. A. Elkink & D. M. Farrell (Eds.), The act of Voting: Identities, Institutions and Locale (pp. 35–55). London: Routledge.

- Compton, P. (1985). An evaluation of the changing religious composition of the population of Northern Ireland. Economic and Social Review, 16(3), 201–224.

- Dixon, P. (2018). What politicians can teach academics: ‘Real’ politics, consociationalism and the Northern Ireland conflict. In M. Jakala, D. Kuzu, & M. Qvortrup (Eds.), Consociationalism and Power-Sharing in Europe: Arend Lijphart’s Theory of Political Accommodation (pp. 55–83). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dornschneider, S., & Todd, J. (2020). Everyday sentiment among unionists and nationalists in a Northern Irish town. Irish Political Studies, 35. doi:10.1080/07907184.2020.1743023

- Evans, J. A., & Tonge, J. (2003). The future of the ‘radical centre’ in Northern Ireland after the Good Friday Agreement. Political Studies, 51(1), 26–50.

- Ganiel, G. (2016). Secularisation, ecumenism and identity on the island of Ireland. In J. C. Wood (Ed.), Christianity and National Identity in 20th Century Europe (pp. 73–89). Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Hayes, B. C., & McAllister, I. (1995). Religious independents in Northern Ireland: Origins, attitudes, and significance. Review of Religious Research, 37(1), 65–83.

- Hayes, B. C., & McAllister, I. (2009). Religion, identity and community relations among adults and young adults in Northern Ireland. Journal of Youth Studies, 12(4), 385–403.

- Hayward, K. (2020). The 2019 general election in Northern Ireland: The rise of the centre ground? Political Quarterly, 91(1), 49–55.

- Hayward, K., & McManus, C. (2019). Neither/Nor: The rejection of unionist and nationalist identities in post-agreement Northern Ireland. Capital and Class, 43(1), 139–155.

- Hayward, K., & Rosher, B. (2020). Political attitudes at a time of flux [ARK Research Update 133, June]. Belfast: ARK, Queen’s University Belfast.

- McAuley, J. W., & Tonge, J. (2010). Britishness (and Irishness) in Northern Ireland since the Good Friday Agreement. Parliamentary Affairs, 63(2), 266–285.

- McNicholl, K. (2018). Political constructions of a cross-community identity in a divided society: How politicians articulate Northern Irishness. National Identities, 20(5), 495–513.

- McNicholl, K. (2019). The Northern Irish identity: Attitudes towards moderate political parties and outgroup leaders. Irish Political Studies, 34(1), 25–47.

- McNicholl, K., Stevenson, C., & Garry, J. (2019). How the 'Northern Irish' national identity is understood and used by young people and politicians. Political Psychology, 40(3), 487–505.

- Mitchell, C. (2006a). Religion, Identity and Politics in Northern Ireland: Boundaries of Belonging and Belief. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Mitchell, C. (2006b). The religious content of ethnic identities. Sociology, 40(6), 1135–1152.

- Mitchell, D. (2018). Non-nationalist politics in a bi-national consociation: The case of the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 24(3), 336–347.

- Moxon-Browne, E. (1983). Nation, Class and Creed in Northern Ireland. Aldershot: Gower.

- Moxon-Browne, E. (1991). National identity in Northern Ireland. In P. Stringer & G. Robinson (Eds.), Social Attitudes in Northern Ireland 1990–91 (pp. 23–38). Belfast: Blackstaff.

- Muldoon, O. T., McNamara, N., Devine, P., & Trew, K. (2008). Beyond gross divisions: National and religious identity combinations [ARK Research Update 58, December]. Belfast: ARK, Queen’s University Belfast.

- Muldoon, O. T., Trew, K., Todd, J., Rougier, N., & McLaughlin, K. (2007). Religious and national identity after the Belfast Good Friday Agreement. Political Psychology, 28(1), 89–103.

- Murtagh, C. (2020). The plight of civic parties in divided societies. International Political Science Review, 41(1), 73–88.

- NISRA. (2013). Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. A note on the background to the religion and ‘religion brought up in’ questions in the census, and their analysis in 2001 and 2011. Retrieved from www.nisra.gov.uk/archive/census/2011/ Background_to_the_religion_ question_2011.pdf

- NISRA. (2020). Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. 2011 Census. Retrieved from https://www.nisra.gov.uk/statistics/census/2011-census

- O’Leary, B. (2019). A Treatise on Northern Ireland: Vol. 1: Colonialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rose, R. (1971). Governing Without Consensus: An Irish Perspective. London: Faber and Faber.

- Stojanović, N. (2018). Political marginalization of ‘others’ in consociational regimes. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft, 12(2), 341–364.

- Taylor, R. (2006). The Belfast agreement and the politics of consociationalism: A critique. Political Quarterly, 77(2), 217–226.

- Todd, J. (2018). Identity Change After Conflict: Ethnicities, Boundaries and Belonging in the Two Irelands. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Todd, J., O’Keefe, T., Rougier, N., & CañásBottos, L. (2006). Fluid or frozen? Choice and change in ethno-national identification in contemporary Northern Ireland. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 12(3-4), 323–346.

- Tonge, J., & Gomez, R. (2015). Shared identity and the end of conflict? How far has a common sense of ‘Northern Irishness’ replaced British or Irish allegiances since the 1998 Good Friday Agreement? Irish Political Studies, 30(2), 276–298.

- Wilford, R. (2010). Northern Ireland: The politics of constraint. Parliamentary Affairs, 63(1), 134–155.

- Wilson, R. (2009). From consociationalism to interculturalism. In R. Taylor (Ed.), Consociational Theory: McGarry and O’Leary and the Northern Ireland Problem (pp. 221–236). London: Routledge.