ABSTRACT

One of the consequences of the Eurozone crisis was the collapse of social concertation. Some authors have explained that the need for fiscal retrenchment deprived governments of resources to offer concessions to trade unions (Regan, 2013). Although these explanations partly explain why social partnership ended, we do not yet know how political actors achieved this institutional change, neither which ideas they used to legitimate it. This article adopts a discursive institutionalist framework (Schmidt, 2008, 2010) to identify the ideas and the causal mechanisms through which political leaders were able to exercise ideational power in a paradigmatic case study: Ireland. The article argues that external constraints during the crisis empowered specific political actors that used the crisis as a ‘moment of political opportunity’ (Béland, 2005, p. 10) to end the social partnership model. They constructed a communicative discourse to legitimise this change based on the ideas that social partnership was dysfunctional and undemocratic.

Introduction

There is abundant scholarly literature on the collapse of social partnership in the EU during the Eurozone crisis (see Molina & Miguélez, Citation2013 for Spain; González Begega & Luque Balbona, Citation2015 for Spain and Portugal; Doherty, Citation2011; D’Art & Turner, Citation2011; Bach & Stroleny, Citation2013; Regan, Citation2013 for Ireland). Most of these accounts focus on macroeconomic constraints (Molina & Miguélez, Citation2013, p. 8; Regan, Citation2013, p. 4) to explain why governments did not resort to social concertation to address the effects of the crisis. Regan, for example, explains that the new macroeconomic context brought about by the Eurozone crisis did not allow governments to offer concessions to trade unions due to the need for fiscal retrenchment and internal devaluation (Regan, Citation2013, p. 4)

However, materialist explanations exclusively based on interests do not tell us the whole of story, as to ‘understand institutional change fully, one must recognize the central role of ideational processes in politics and policymaking’ (Béland, Citation2007, p. 23). Besides, materialist accounts embedded within Historical institutionalist perspectives tend to identify institutional change as something abrupt (Schmidt, Citation2010, p. 14), and thus mask the ongoing ideological contestation that exists over certain institutions in times of stability.

By adopting a Discursive institutionalist perspective (Schmidt, Citation2008, Citation2010), this article’s contribution to theoretical debates that link ideas with institutional change is twofold. First, the article adds to theoretical discussions on incremental versus revolutionary change by showing that institutions-even when they are broadly supported by political actors – are under constant ideological dispute. Second, the article goes beyond the argument that ideas ‘matter in politics’ (Rueschemeyer, Citation2006, p. 1) to demonstrate how these ideas matter when they are in interaction with other elements. In this sense, the article proposes a causal mechanism that unfolds the causal relations between ideas, conflict and power to explain institutional change.

In order to test these arguments, the article explains the discursive deconstruction of social partnership in a paradigmatic case study: Ireland. The end of the social partnership model was the most important institutional change in Ireland during the crisis (Maccarrone et al., Citation2019, p. 329). The two major Irish political parties, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, had relied since 1987 on social dialogue with social partners to negotiate wages and to agree upon welfare and labour policies by renewing social partnership agreements every three years (O’Donnell & O’Reardon, Citation2000). Some authors acknowledge that this model of socioeconomic governance achieved social and political stability (notably by reducing industrial action) that was not only beneficial to economic prosperity, but also had the support of the main political parties and civil society (Baccaro & Simoni, Citation2004; Collins, Citation2004).

Nevertheless, when the crisis worsened in 2009, the Fianna Fáil/Green government and the Irish Congress of Trade Unions (ICTU) were unable to renew the wages agreement. Moreover, the Fine Gael/Labour government elected in February 2011 also opted for unilateralism and did not restart national social dialogue with trade unions. With the exception of two sectoral agreements signed by public service trade unions and the governments in 2010 and 2013, no national pacts were signed during the crisis period.Footnote1 Empirically, the Irish case gives us fundamental insights about the relationship between ideas, conflict and power. Some authors argue that the end of Irish social partnership was due to the decline of trade union’s power (Culpepper & Regan, Citation2014). Culpepper and Regan explain that Irish trade unions could not offer neither the ‘stick’ (strikes) nor the ‘carrot’ (mobilising consent) to the government, and therefore the latter did not need to include them in policymaking processes (Culpepper & Regan, Citation2014). This article takes up this argument with the objective to offer a complementary explanation based on the changes of power relations within the government. Although these changes have been pointed out by the literature (Murphy et al., Citation2014; Regan, Citation2017), they have not been systematically reviewed from an ideational perspective to explain how the empowerment of certain sectors within the government served as a ‘moment of political opportunity’ (Béland, Citation2005, p. 10) to advance negative ideas against social partnership.

This is important because, as this article empirically shows, despite of the stability of the Irish social partnership model, this institution was ideologically questioned before the Eurozone crisis. The model was sustained due to the existence of old powerful agents (mainly leaders of Fianna Fáil and the Prime Minister office) and pragmatic reasons (the reduction of industrial action in the beginning, and electoral interests later). To the contrary, other political, economic and societal actors (above all the Minister of Finance, but also political parties such as Fine Gael, the media and business associations) had shown their ideological disagreement with the model before the Eurozone crisis but they did not have the power to dismantle it.

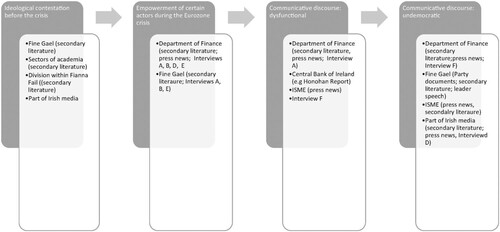

Moreover, the article demonstrates that when external constraints during the crisis strengthened those agents, they constructed a communicative discourse(Schmidt, Citation2000, Citation2002) to legitimise the end of social partnership based on the ideas that social partnership was economically dysfunctional(detrimental to economic competitiveness) and undemocratic.

With the objective to test these arguments, this article uses process tracing methods, which are useful to ‘demonstrate how such ideas are tied to action’ (Schmidt, Citation2008, p. 308). In so doing, it triangulates different types of data such as documentary sources, secondary literature, journalistic accounts, media news and biographic books. The empirical evidence of this research is also supported by the data collected in the seven elite interviews that were carried out by the author in January 2017. Interviews were made to those responsible for negotiating social partnership agreements in the beginning of the Eurozone crisis such as representatives from the trades unions, senior civil servants and politicians involved in the administration and negotiations of social pacts. All interviews were semi-structured, anonymous, and lasted between one and two hours.

The article proceeds as follows. The next section develops the analytical framework based on the Discursive institutionalist approach. The third section explains incremental ideational change in Ireland before the crisis. The fourth section shows how the crisis empowered certain political and societal actors. The fifth section analyses the communicative discourse developed by these actors to legitimate the end of the social partnership. The last section concludes.

Conflict, ideational power and institutional change

This article proposes an analytical framework based on the Discursive institutionalist approach to trace the causal connection between ideas and institutional change. This relationship has often been contested because it is difficult to show how ideas alone cause change in institutions (Campbell, Citation2002, p. 22). Spite of this difficultness, some scholars have shown that ideas can influence politics through their interaction with other factors in a sequence (Rueschemeyer, Citation2006, p. 13). We draw on this argument and propose a mechanism that unfolds the causal power of ideas when they are in relation to other factors such as conflict and power.

First, the article is inspired on ideational analyses because they help us to reveal the conflict beneath the surface that exists in times of institutional stability (Peters, Pierre, & King, Citation2005, p. 1275). Second, it is claimed here that ideas on their own have little enforcement power if they are not promoted by powerful actors (Béland, Citation2005, p. 10). Therefore, the concept of ideational power is usefulbecause it helps us find the mechanisms through which ideas and power interact (Béland, Carstensen, & Seabrooke, Citation2016, p. 315). Third, the article claims that although ideational change is in most cases incremental, political actors need to find ‘moments of political opportunity’ (Béland, Citation2005) to bring ideas to the fore in the political debate. In order to do so, political actors construct a communicative discourse to place ideas in the political agenda that serve to drive and legitimise institutional change. In the next sections, we elaborate further our theoretical proposals.

Conflict and ideational change

Institutional change is in most cases the result of a conflict over ideas that comes from periods of institutional stability (Peters et al., Citation2005, p. 1278). Ideas do not emerge from a vacuum in moments of crisis. Whereas materialist accounts fail ‘to identify the political conflict and dissensus with at the surface might appear stable’ (Peters et al., Citation2005, p. 1278), ideational accounts are useful to identify ideational change, ‘how old ideas fail and new ideas come to the fore’ (Schmidt, Citation2010, p. 14). Therefore, it is important to pay attention to how ideas change over time (Carstensen, Citation2011, p. 597).

In relation to this, Discursive institutionalism distinguishes evolutionary from revolutionary change (Schmidt, Citation2010). Evolutionary change involves incremental alterations of ideas usually associated with endogenous factors, whereas revolutionary change is related to sudden changes of ideas normally brought about by exogenous factors.

In addition, each type of change implies different levels of ideas. Revolutionary change is easier at the level of programmatic ideas at the cognitive level, which are paradigms that aim to provide solutions to policy problems (Béland, Citation2007; Hall, Citation1993). On the other hand, incremental change also requires changes in ‘deep philosophical ideas’ related to normative values that ‘usually operate slowly by adapting themselves naturally to new circumstances’ (Schmidt, Citation2014, p. 196). The analysis of both cognitive and normative ideas is fundamental when we want to account for ‘paradigm shifts’ (Hall, Citation1993) because ideational change can only be successful if both programmatic and philosophical ideas are connected (Béland, Citation2005, p. 8). Therefore, the first proposal of this article is that to account for ideational change we need to identify ideational conflict in times of stability to recognise both normative and cognitive ideas.

Power and moments of political opportunity

But in what way do these ideas matter? Carstensen and Schmidt argue that one significant way is through agents’ promotion of certain ideas at the expense of the ideas of others (Carstensen & Schmidt, Citation2016, p. 319). Therefore, before analysing how ‘policy ideas are communicated and translated into practices’ (Campbell, Citation2002, p. 21), we must identify the political and societal actors that have the ideational power to advance or resist alternative ideas (Carstensen & Schmidt, Citation2016). Although entrepreneurs contest ideas in times of stability, it is common for ‘power-seeking actors’ (Carstensen, Citation2011, p. 597) to use moments of crisis to push their ideas. When institutions are contested, powerful actors use ideas as ‘weapons’ to achieve institutional transformation (Blyth & Mark, Citation2002, p. 39).

In this sense, ‘moments of political opportunity’ (Béland, Citation2005, p. 10) are important here because this is when entrepreneurs are able to bring their preferred solutions to the fore in the political debate to provide a solution to an existing problem (Béland, Citation2005, p. 10). This was already put forward by Blyth and Mark (Citation2002) when they explained that ideas not only help powerful actors to ‘define a crisis as a crisis’ but also to plan their strategies to face it (Blyth & Mark, Citation2002, p. 10). The second proposal of this article is that, in order to link ideas with institutional change, we need to identify the empowered political actors that are able to exercise ideational power in ‘moments of political opportunity’ (Béland, Citation2005).

Bringing ideas to the fore: communicative discourse

Finally, how do political actors bring ideas to the fore in the political debate? As Peters et al. (Citation2005) argues, ‘ideas are crucial elements in the battle to place issues in the agenda’ (Peters et al., Citation2005, p. 1295). Political discourses articulate different forms, types and levels of ideas. Schmidt distinguishes two types of discourse: coordinative and communicative discourse (Schmidt, Citation2000, Citation2002). Coordinative discourse is that used by policy makers during discussions and bargaining in the policymaking process whereas communicative discourse ‘encompasses the wide range of political actors who bring the ideas developed in the context of the coordinative discourse to the public for deliberation and legitimation’ (Schmidt, Citation2010, p. 3). Agents can use their ‘power over ideas’ in the context of communicative discourse to impose their ideas and resist alternative ones (Carstensen & Schmidt, Citation2016, p. 323).

On the other hand, agents can also use their ‘power through ideas’ to persuade other political actors (Carstensen & Schmidt, Citation2016, p. 323). In relation to this, politicians use communicative discourse strategically and deliberately to achieve public support and legitimise specific programmes (Béland, Citation2007). The analysis of communicative discourse allows us to observe ‘how and when ideas in discursive interactions enable actors to overcome constraints’ (Schmidt, Citation2010, p. 4). Therefore, the third and last step of the causal mechanism proposed here claims that empowered political actors legitimate their ideas through communicative discourse. .

Incremental ideational change in Ireland before the Eurozone crisis

This section evaluates the incremental ideational change that led to the collapse of social partnership in Ireland. This change was mostly incremental for two reasons. First, the model had weak ideological embedding in the main Irish political parties. Second, negative ideas on this policymaking model had also evolved since very early, leading to the model being in constant process of contestation.

One the one hand, the social partnership ideology was never embedded in the major Irish political parties, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael (Doherty, Citation2011, p. 384). This made the Irish social partnership model heavily dependent on the entrepreneurship and ideas of specific political actors, mostly from Fianna Fáil (Roche, Citation2009). Roche dates the origins of social partnership to the ideas of the former Fianna Fáil leader, Sean Lemass, who was crucial in obtaining the trade unions’ support for the party (Roche, Citation2009, p. 185).

Although placed on the centre-right of the political spectrum, Fianna Fáil’s commitment to the trade unions had converted it into a corporatist party par excellence. As Begg explains: ‘The Fianna Fáil Party has always worked – and with some success – to secure trade union support, much to the chagrin of the Labour Party’ (Begg, Citation2016, p. 149). Later, Lemass’ ideas were put in practice by two other Fianna Fáil leaders, Bertie Ahern and Charles HaugheyFootnote2 (Roche, Citation2009). Ahern, who was Taoiseach from 1997 to 2008, became the ‘political guarantor of social partnership’ when he governed with ministers that were more reluctant to negotiate with trade unions (Roche, Citation2009, p. 200). The Irish social partnership became the responsibility of the Taoiseach’s office.

Although the processes of negotiations with social partners were never formally institutionalised, some characteristics of the process gave it some regularity and stability. Therefore, social partnership became a central part of Irish policymaking since the fiscal crisis of the 1980s (Hardiman, Murphy, & Burke, Citation2008, p. 618). The role of the National Economic and Social Council (NESC) was central to this process as it had been responsible for producing policy documents that served as benchmarks for the negotiations since the late 1980s (Nye, Citation2001, p. 192). Before the Eurozone crisis, negotiations with social partners were therefore coordinated by the Department of the Taoiseach (Murphy & Hogan, Citation2008, p. 591) where senior officials and the prime minister were responsible for coordinating the discussions with NESC and bargaining with social partners. This led to the emergence of a stable model of socioeconomic governance even though there was a lack of formal institutions. In fact, the programmes elaborated by NESC ‘were more or less endorsed by governments and parties of all political hues’ (Roche, Citation2009, p. 200).

Nevertheless, negative ideas about social partnership slowly evolved before the crisis, notably within Fine Gael but also in the media and certain sectors of academia (Baccaro & Simoni, Citation2004). Political parties such as Fine Gael have traditionally expressed reluctance about the social partnership model and had relied on this strategy for pragmatic reasons rather than ideological commitment (Doherty, Citation2011; Roche, Citation2009). Since the early 1990s, Fine Gael criticised social partnership by saying that it was undemocratic (The Irish Times, Citation2007). Although it never tried to openly dismantle it, it changed its procedures when it was in government. For example, in 1996, the Fine Gael Prime Minister, John Bruton, created the Community Pillar to invite non-profit organisations to social partnership (Larragy, Citation2006, p. 1). The objective was to inject participatory democracy into the model (Meade, Citation2005, p. 364).

Moreover, part of the Irish media had also shown their doubts about the Irish social partnership model before the crisis. In 2001, the Irish Times published an article title ‘The Hypocrisy of social partnership’ where Kieran Allen questioned the ability of social partnership to redistribute wealth (Allen, Citation2001). Negative ideas on social partnership had already been present within certain sectors of the Irish academia before the crisis as some economists had argued that social partnership was ‘counterproductive’ (Baccaro & Simoni, Citation2004, p. 1). Whereas social partnership had survived in the 1990s thanks to the association between this model of socioeconomic governance and the economic growth (Regan, Citation2016), in the late1990s some economists started arguing that social partnership had deviated from its initial economic objectives. There were voices against negotiating with social partners even within Fianna Fáil, leading to the model’s ‘weak ideological foundations’ (Doherty, Citation2011, p. 384). This was the case of the former FF finance minister Charlie McCreevy who was removed from his position in 2004 when he ignored the commitments adopted by the Taoiseach in the context of the negotiations of the Programme for Prosperity and Fairness (Regan, Citation2012, pp. 148–149).

The Eurozone crisis: moment of political opportunity

During the Eurozone crisis, political actors that held negative ideas about the social partnership were empowered, notably the Ministers of Finance and Fine Gael. First, the cabinet reshuffle undertaken on 7th May 2008 in the Fianna Fáil/Green coalition government led to the appointment of new leaders that were not close to social partnership processes and dynamics. Second, the general elections of February 2011 resulted in the victory of Fine Gael, which formed a government with the Labour Party and used the crisis to push for the end of the social partnership.

On the one hand, the cabinet reshuffle led to the ‘political guarantor of social partnership’ (Roche, Citation2009, p. 200) and former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, being replaced by Brian Cowen. Although Brian Cowen had not shown special antipathy towards the social partnership while he was the Minister of Finance, the social partnership model was ‘less central to his political identity and reputation’ (Roche, Citation2009, p. 204). Besides, the new Minister of Finance, Brian Lenihan, who adopted the leading role in managing the crisis, had openly expressed his opposition to the social partnership. Neither Brian Cowen nor Brian Lenihan had close relationships with trade unions (CitationInterview A). For these reasons, the shifts of power after the cabinet reshuffle in 2008 were detrimental to the social partnership. The arrival of people that had already shown publicly their negative views about trade unions decreased trust between the government and trade unions which is central for successful negotiations (Adshead, Citation2011, p. 87) A representative from the UNITE trade union explained to us in the interview that when the Eurozone crisis started:

They had at the helm of Fianna Fáil people who didn’t really understand the trade unions, and were more susceptible to the ideological line put out by Department of Finance … I think they had to make a choice. Whether to continue down the road of Social Partnership or to side with finance capital. And they sided with finance capital. (CitationInterview A)

As a result, the Irish Department of Finance had more power than the Department of the Taoiseach and other governmental departments, which at the same time had consequences for the dynamics of social partnership (Regan, Citation2017, p. 125). Senior officials at the Taoiseach’s office who had coordinated the social partnership process with social partners in the past had retired or had been moved to other departments (Regan, Citation2016). In turn, the office of the Taoiseach became not only became very small but officials in charge with negotiating with social partners had disappeared, and only remained there those who were more reluctant to negotiate (CitationInterview B). The new Minister of Finance, Brian Lenihan was central for the end of social pacts as he did not believe that trade unions could play a role to solve the crisis (Murphy et al., Citation2014). During the negotiations of the wage agreement with trade unions in 2009 the differences between the Prime Minister and Brian Lenihan came to the surface. Whereas Brian Cowen wanted an agreement with the trade unions, Brian Lenihan opposed to negotiate and preferred to act unilaterally to impose cuts (CitationInterview D). The differences between Brian Cowen and the Minister of Finance regarding social partnership led to a divergence of views about how to solve the crisis. Whereas the Prime Minister wanted to preserve some kind of national consensus given that Fianna Fáil was rooted in that tradition, the Minister of Finance, who came from a technocratic background, preferred to solve the crisis unilaterally(CitationInterviews, A, CitationE).

Moreover, the general elections of February 2011 were won by Fine Gael and this resulted in the consolidation of anti-social partnership procedures and dynamics. The Troika’s arrival and the implementation of the Memorandum of Understanding confirmed the empowered role of Finance. First, the negotiations with the Troika placed the Department of Finance at the centre of the main decisions (CitationInterview B). Second, the strengthening of Finance was consolidated through a series of institutional reforms implemented by the Fine Gael/Labour coalition.

The government created the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform led by the Minister of Public Expenditure and Reform (Brendan Howlin, 2011-2016) on 6th July 2011. This new department was split off from the Department of Finance, and its objective was to address the specific challenges of structural reforms brought about by the Eurozone crisis. In practice, this meant that the importance of the departments that were responsible for fiscal policy and structural reforms increased given that since it now had two ministers and more influence in decision-making processes. In addition, the Fine Gael/Labour government created the Economic Management Council, formed by the Prime Minister, Enda Kenny, the Deputy Prime Minister, Eamon Gilmore, the Minister of Finance, Michael Noonan, and the Minister of Public Expenditure and Reform, Brendan Howlin. This Council centralised all decision-making on the management of the crisis and negotiations with the Troika (CitationInterview E).

In addition, the political and institutional changes under the Fine Gael/Labour coalition led to a decrease in the influence of certain political actors that had been central to the social partnership model before the crisis. The government moved the Labour Market Policy Unit, which dealt with industrial relations and labour markets issues, from the Department of Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation to the Departments of Education and Social Protection (Regan, Citation2013, p. 139), which had less enforcement power. Also, the role of NESC changed during the crisis and its influence on government policymaking was reduced (Regan, Citation2016). Other political actors, such as the employer’s organisation and the banking sector, became more influential during the Eurozone crisis together with the Department of Finance and the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform (Doherty, Citation2011). Regan explains that the small firms’ association (SFA) increased its participation in the policymaking process during the crisis and it acquired greater influence since then (Regan, Citation2013, p. 17).

Finally, the empowerment of certain entrepreneurs usually reflects a reduction in the power of other political actors. Many authors explain that the last decades have witnessed the decline of trade unions’ power and legitimacy (Culpepper & Regan, Citation2014, p. 723; D'Art & Turner, Citation2011; Regan, Citation2013, p. 16). Irish trade unions have lost their power to veto reforms due to lower union density (D'Art & Turner, Citation2011, p. 157; Geary, Citation2016, p. 134) and the loss of mobilisation capacity (Cox, Citation2012). Besides, it has been noted that trade unions lacked a discursive critique of the crisis and a strategy to overcome their exclusion from the policymaking partly because theyhad accepted the need for some austerity (CitationInterviews, A, CitationB).

Communicative discourse: deconstructing social partnership

Those political and societal actors that were empowered during the crisis formed ‘discourse coalition’ (Schmidt, Citation2014), and they elaborated a communicative discourse against the social partnership model based on two ideas. The first idea argued that the social partnership was ‘dysfunctional’ because it had created counterproductive effects that were detrimental to economic growth. This idea is placed at the cognitive level because it ‘serves to justify policies and programs by speaking to their interest-based logic’ (Schmidt, Citation2008, p. 306). On the other hand, the second idea underpinning the communicative discourse was that social partnership was ‘undemocratic’. This idea is placed at the normative level because it ‘attaches values to political action and serves to legitimate the policies’ (Schmidt, Citation2008, p. 3017).

The social partnership as dysfunctional

As we have seen above, the lack of ideological commitment of Fianna Fáil to the social partnership became clear when the new leadership was appointed after the cabinet reshuffle in 2008. The main political entrepreneur for the deconstruction of social partnership was the new Minister of Finance, Brian Lenihan, who argued that social partnership was a part of the problem and not the solution to the economic difficulties raised by the crisis, and issued a report to that effect (Regan, Citation2013, p. 17). One of the arguments sustained by the Ministry of Finance to justify the end of social dialogue was that public sector unions had ‘too much influence over policymaking’ (CitationInterview A). In that sense, Brian Lenihan saw trade unions as a part of the problem rather than the solution (CitationInterview B). In the report, the Department of Finance established a direct relationship between the need to restructure and strengthen the department and decreasing ‘the dominance of the social partnership process’ (Minihan, Citation2010). Also, in December 2009, Brian Lenihan declared to the press that the social partnership had done ‘enormous damage’ to the Irish financial system (Rogers, Citation2010).

Another key ideational element put forward by the Ministry of Finance was that the social partnership had created a series of dysfunctionalities that were detrimental to economic growth. These ideas that associated social partnership with the causes of the economic crisis regained importance during the Eurozone crisis. Empowered agents exercised their ‘power over ideas’(Carstensen & Schmidt, Citation2016, p. 323) to impose the end of social partnership and exclude trade unions from the decision-making processes. The Department of Public Expenditure also supported the view that many problems that had led to the crisis required a different approach to social partnership (CitationInterview G). In addition to the internal reports of the Ministry of Finance, different entrepreneurs in the banking sector also developed this argument in various reports that became influential in the political debate (CitationInterview C). One of them was the ‘Honohan report’, named after Patrick Honohan, the governor of the Central Bank of Ireland (CBI), an economist and a member of academia who was appointed as the governor of CBI in September 2009. In an article prepared for the World Bank, Honohan explains that social partnership had proved useful to achieve wage moderation only in the first decades of implementation, but from the 2000s it became associated to the dysfunctionalities of the property bubble:

In each negotiation, in order to obtain or cement agreement of the unions to moderate basic pay trends, the government offered policy concessions, generally including an explicit or implicit understanding that income tax would be reduced. These tax reductions did help to buy wage restraint in the 1980s and 1990s, but left the government accounts exposed to a downturn (Honohan, Citation2009, p. 3)

The discursive deconstruction of the social partnership as economically ‘dysfunctional’ is associated to the argument put forward by Dukelow (Citation2015) about the use of the crisis by Irish governments to reinforce ‘its dominant neo-liberal policy paradigm’ (Dukelow, Citation2015, p. 94). Entrepreneurs established a link between the social partnership and the ‘mistakes’ associated to the property bubble. Social partnership was blamed for having sustained an economic model that was over-reliant on the revenues of the bubble to increase social spending (CitationInterview F). As the revenues were no longer available, this opened the window to justify austerity and the end of social partnership as the model of socioeconomic governance that had underpinned it:

The breakdown of social partnership combined with the congruence between the government’s budgetary decisions and advocates of austerity further shifted the power balance from the unions to those who argued for austerity (Dukelow, Citation2015, p. 102)

The social partnership as undemocratic

The discursive deconstruction of social partnership was also based on the argument that the social partnership was ‘undemocratic’. Empowered agents exercised their ‘power through ideas’(Carstensen & Schmidt, Citation2016, p. 323) to make their normative perspective on social partnership hegemonic. This idea had also been developed by different Irish political actors and academics before the crisis (Collins, Citation2004; Teague & Donaghey, Citation2009; Gaynor, Citation2009). Most of these critics, supporters of liberal representative democracy, consider that social partnership is illegitimate because it expropriates ‘elective assemblies and governments of their legitimate prerogatives, forcing them to ratify decisions reached in private arenas’ (Baccaro, Citation2006, p. 202). Whereas social democracy defends the existence of intermediate institutions such as social partnership, liberal democracy advocates that these institutions undermine democracy. In the same line, Gaynor explains that these critics argue that social partnership ‘undermines the sovereign position of elected political representatives, with key policy formulation and decision-making taking place in forums outside the institutions of representative democracy’ (Gaynor, Citation2009, p. 3013).

The issue of transparency is another ideational element linked to the idea of social partnership as undemocratic. Supporters of this idea complained about ‘the lack of clear and widely acceptable criteria to justify the involvement of some organizations and the (inevitable) exclusion of others’ (Baccaro, Citation2006, p. 202). Some authors analyse how social partnership in Ireland developed ‘clientelistic politics’ (Cox, Citation2012, p. 2) as ‘membership in the “Social Partnership” became a sort of “trampoline” for a fast start in a political career’ (Byszewski, Citation2012, p. 154). As Ross and Webb put it: ‘social partnership had become an industry unto itself’ (Ross & Webb, Citation2010). The Department of Finance considered that social partnership had led to a democratic deficit because the government negotiated with the unions how to allocate expenditure (CitationInterview F).

Historically, the centre-right political party, Fine Gael, was the main political entrepreneur that had put forward these ideas and it became the biggest party in government since February 2011 (in coalition with the Labour Party). As Roche explains, ‘concern with the democratic accountability of social partnership has been an abiding issue within Fine Gael and has made for considerable ambivalence in the Party’s stance on the process’ (Roche, Citation2009, p. 196). Worried about issues of democratic accountability, Fine Gael – under the leadership of John Bruton, one of the supporters of liberal representative democracy – campaigned in the 1990s to open the social partnership process to NGOs and civil organisations rather than only to trade unions and business organisations (Roche, Citation2009). However, Fine Gael was not the only actor that criticised the democratic deficit of social partnership. These concerns were also shared by specific personalities of Fianna Fàil, the Labour Party and by community and voluntary groups (Roche, Citation2009).

Although the former Fianna Fàil Minister of Finance, Charlie McCreevy, was not against the social partnership (Begg, Citation2016, p. 158), on one occasion he had also declared that ‘he derived his mandate from the electorate’ (Roche, Citation2009, pp. 200–201). One year before the crisis erupted, Charlie McCreevey and the ‘political guarantor of social partnership’, Bertie Ahern, engaged in a discursive struggle about the democratic deficit of social partnership. In an interview given by Mcgreevy for a book,Footnote3 he had argued that trade unions wanted social partnership to be the place ‘where all kinds of decisions would be made’ (The Irish Times, Citation2007). In response, Ahern defended the democratic nature of social partnership because it was based on:

A recognition of the proper and distinct roles of government, on the one hand, and the legitimate contribution to public life of the social partners who, entirely in their own right, exercise very significant influence over the economic and social life of this country (The Irish Times, Citation2007)

One of the challenges for the continuing development of Social Partnership is the need to create a greater sense of ownership and transparency in the process. The process must be more open to scrutiny. The views of social partnership as antidemocratic have been extended to other lobbying activities. (Fine Gael and the Labour Party, Citation2005)

The social partnership model practised by previous governments had become a closed shop, where decisions with national consequences were made behind closed doors by a chosen few, accountable to nobody. (Kenny, Citation2015)

Part of the Irish media, which has traditionally produced and legitimised the neoliberal discourse (Phelan, Citation2007, p. 30), had two roles during the crisis. On the one hand, the main newspapers such as the Irish Times or the Independent served as the ‘megaphone’ that gave voice to the views of politicians and business organisations and disseminated the discursive struggles on social partnership. On the other hand, editorials and opinion articles helped to communicate a negative narrative of social partnership. With the aim of uncovering the ‘industry’ of social partnership, in 2009 the Independent published personal information such as the salaries, houses and pension entitlements of trade union leaders (Quinlan, Citation2009).

In 2015, the Independent published an article where Dan ÒBrien shown his scepticism about the arrangements of social partnership because they ‘undermine the parliament’ (O’Brien, Citation2015). The media played a central role in disseminating negative views about social partnership (CitationInterviews, A, CitationB). The journalist, Dan O’Brien, also published various articles between 2013 and 2015 warning about the risks of going back to social partnership practices. In one of these articles, he concluded:

Social partnership is ill-suited to countries with weak political institutions. It is now clear that whatever reform of Ireland’s political infrastructure takes place, it will not lead to radically more effective institutions. As such, social partnership should rest in peace (O’Brien, Citation2013)

Conclusions

This article has shown that ideas played an important role in the collapse of social partnership in Ireland but that ideas needed powerful actors to be communicated and to be effective. The ideas that social partnership was dysfunctional and undemocratic had existed before the crisis but it was the emergence of external constraints that allowed the carriers of those ideas to bring it to the forefront of political debate and achieve the widespread acceptance of Irish political, economic and societal actors. Social partnership had been widely supported by political actors before the crisis but they were not in power when financial problems worsened, making the social partnership model more susceptible of being altered or collapsing due to the lack of formal institutions.

The article has demonstrated that the Eurozone crisis functioned as a ‘moment of political opportunity’ (Béland, Citation2005) for the Department of Finance, Fine Gael, the banking sector, business associations. They built a communicative discourse based on the combination of a cognitive idea that connected social partnership with the ‘failed’ Keynesian paradigm and a normative idea that set social partnership in opposition to democracy. The first idea connected exogenous factors – the risk of financial default – with endogenous factors – lack of wage moderation during the property bubble – to justify a shift in the political economy paradigm (Hall, Citation1993) to eliminate social partnership. The second idea was related to deep values about how to organise the democratic political system and also combined exogenous and endogenous factors. The arguments that social partnership was ‘clientelistic’ had strong resonance at a time when the narrative of the crisis as resulting from the mismanagement of public finances became widely accepted among the majority of Irish society (Fraser, Murphy, & Kelly, Citation2013, p. 41).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Catherine Moury for her contribution to earlier drafts of this paper. I am also grateful for the constructive feedback received from the anonymous peer reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).Acknowledgments: I would like to thank Catherine Moury for her contribution to earlier drafts of this paper. I am also grateful for the constructive feedback received from the anonymous peer reviewers.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Angie Gago

Angie Gago is a post-doc researcher at the University of Lausanne (UNIL). She obtained her PhD in Political Studies at the University of Milan and she is also a Master’s in Politics and Democracy (UNED) and International Relations (London Metropolitan University). Her research interests are the Eurozone crisis, public policies, welfare state reforms and concertation processes. She has presented her work at various conferences (CES, ECPR, ESPanet, etc.) and it has been published in various books and journals such as South European Society and Politics.

Notes

1 Social partners and the government signed the last social partnership agreement, ‘Towards 2016: Review and Transitional Agreement 2008/2009’ in November 2008 (Regan, Citation2013, p. 134).

2 Bertie Ahern was Minister for Labour in 1987 and Prime Minister from 1997 to 2008 and Charles Haughey Prime Minister was Prime Minister from 1987 to 1992.

3 Saving the future – How social partnership shaped Ireland’s economic success, by Tim Hastings, Brian Sheehan and Pádraig Yeates.

References

- Adshead, M. (2011). An advocacy coalition framework approach to the rise and fall of social partnership. Irish Political Studies, 26(1), 73–79.

- Allen, K. (2001). The Hypocrisy of social partnership.The Irish Times, 14 February, 2001.

- Baccaro, L. (2006). Civil society meets the state: Towards associational democracy? Socio-Economic Review, 4, 185–208.

- Baccaro, L., & Simoni, M. (2004). The Irish social partnership and the Celtic tiger phenomenon. Unpublished paper, International Institute for Labour Studies. Working paper DP/154/2004.

- Bach, S., & Stroleny, A. (2013). Public service employment restructuring in the crisis in the UK and Ireland: Social partnership in retreat. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 19(4), 341–357.

- Begg, D. (2016). Ireland, small open economies and European integration. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Béland, D. (2005). Ideas and social policy: An institutionalist perspective. Social Policy & Administration, 39, 1–18.

- Béland, D. (2007). Ideas and institutional change in social security: Conversion, layering, and policy drift. Social Science Quarterly, 88, 20–38.

- Béland, D., Carstensen, M. B., & Seabrooke, L. (2016). Ideas, political power and public policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(3), 315–317.

- Blyth, M., & Mark, B. (2002). Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Byszewski, D. (2012). Social partnership in Ireland. Warsaw Forum of Economic Sociology, 3:1(5), 139–163.

- Campbell, J. L. (2002). Ideas, politics, and public policy. Annual Review of Sociology, 28(1), 21–38.

- Carstensen, M. B. (2011). Ideas are not as stable as political scientists want them to be: A theory of incremental ideational change. Political Studies, 59(3), 596–615.

- Carstensen, M. B., & Schmidt, V. A. (2016). Power through, over and in ideas: Conceptualizing ideational power in discursive institutionalism. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(3), 318–337.

- Collins, N. (2004). Parliamentary democracy in Ireland. Parliamentary Affairs, 57(3), 601–612.

- Cox, L. (2012). Challenging austerity in Ireland. Concept, 3(2), 1-6.

- Culpepper, P. D., & Regan, A. (2014). Why don’t governments need trade unions anymore? The death of social pacts in Ireland and Italy. Socio-Economic Review, 12(4), 723–745.

- D’Art, D., & Turner, T. (2011). Irish trade unions under social partnership: A Faustian bargain? Industrial Relations Journal, 42(2), 157–173.

- Doherty, M. (2011). It must have been love … but it’s over now: The crisis and collapse of social partnership in Ireland. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 17(3), 371–385.

- Dukelow, F. (2015). ‘Pushing against an open door’: Reinforcing the neo-liberal policy paradigm in Ireland and the impact of EU intrusion. Comparative European Politics, 13(1), 93–111.

- Featherstone, K. (2001). The political dynamics of the vincoloesterno: the emergence of EMU and the challenge to the European Social Model. Unpublished manuscript. Queen’s Papers on Europeanisation.

- Fine Gael and Labour Party. (2005). A new departure for social partnership. Retrieved from https://www.labour.ie/download/pdf/new_departure.pdf

- Fraser, A., Murphy, E., & Kelly, S. (2013). Deepening neoliberalism via austerity and ‘reform’: The case of Ireland. Human Geography, 6, 38–53.

- Gaynor, N. (2009). Deepening democracy within Ireland’s social partnership. Irish Political Studies, 24(3), 303–319.

- Geary, J. (2016). Economic crisis, austerity and trade union responses: The Irish case in comparative perspective. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 22(2), 131–147.

- González Begega, S., & Luque Balbona, D. (2015). The economic crisis and the erosion of social pacts in Southern Europe: Spain and Portugal in comparison. RevistaInternacional de Sociología, 73(2), 1-13.

- Hall, P. (1993). Policy paradigms, social learning and the state: The case of economic policy-making in Britain. Comparative Politics, 25, 275–296.

- Hardiman, N., Murphy, P., & Burke, O. (2008). The politics of economic adjustment in a liberal market economy: The social compensation hypothesis revisited. IrishPoliticalStudies, 23(4), 599–626.

- Hardiman, N., & Regan, A. (2013). The politics of austerity in Ireland. Intereconomics, 48(1), 4–32.

- Honohan, P. (2009). What went wrong in Ireland. Prepared for the World Bank.

- Interview C. (18 January 2017). Representative of the Central Bank of Ireland.

- Interview D. (19 January 2017). Representative of IMPACT.

- Interview E. (18 January 2017). Representative of SIPTU and ICTU.

- Interviewee A. (16 January 2017). Representative of Unite.

- Interviewee B. (16 January 2017). Representative of the National Economic and Social Council (NESC).

- Interview F. (20 January 2017). Representative of the Department of Finance.

- Interview G. (20 January 2017). Representative of the Department of Public Expenditure.

- The Irish Examiner. (2015). Burton rules out return to social partnership. The Irish Examiner, 19 January, 2015.

- The Irish Times. (2007). McCreevy wary of social partnership. The Irish Times.28 June, 2007.

- Kenny, E. (2015). Speech at the opening of the National Economic Dialogue (Thursday 16 July 2015). Retrieved from http://www.taoiseach.gov.ie/eng/News/Taoiseach's_Speeches/Speech_by_the_Taoiseach_Enda_Kenny_T_D_Opening_of_the_National_Economic_Dialogue_Dublin_Castle_Thursday_16_July_2015.html

- Larragy, J. (2006). Origins and significance of the community and voluntary pillar in Irish social partnership. Economic & Social Review, 37(3), 375–398.

- Maccarrone, V., Erne, R., & Regan, A. (2019). Ireland: life after social partnership. In T. Müller, K. Vandaele & J. Waddington (Eds.), Collective bargaining in Europe: towards an endgame. ETUI.

- Meade, R. (2005). We hate it here, please let us stay! Irish socialpartnership and the community/voluntary sector’sconflicted experiences of recognition. Critical Social Policy, 25(3), 349–373.

- Minihan, M. (2010, December 15). Union leaders reject Lenihan’s criticism of social partnership. Retrieved from www.irishtimes.com

- Molina, O., & Miguélez, F. (2013). From negotiation to imposition: Social dialogue in times of austerity in Spain. Unpublished paper. International Labour office Working Paper No. 51.

- Moury, C., & Standring, A. (2017). Going beyond the Troika’: Power and discourse in Portuguese austerity politic. European Journal of Political Research, 56, 660–679.

- Murphy, O., et al. (2014). Brian Lenihan: In calm and crisis. Ireland: Merrion Press.

- Murphy, G., & Hogan, J. (2008). Fiannafáil, the Trade Union Movement and the politics of Macroeconomic Crises, 1970–82. Irish Political Studies, 23(4), 577–598.

- Nye, M. (2001). Managing the boom: Negotiating Irish social partnership in an expanding economy. Irish Political Studies, 16(1), 191–199.

- O’Brien, D. (2013). Social partnership a danger in politically flawed Ireland. The Irish Times, 30 August, 2013.

- O’Brien, D. (2015). The case against social partnership is overwhelming. The Independent. 6 March, 2015.

- O’Donnell, R., & O’Reardon, C. (2000). Social partnership in Ireland’s economic transformation. In G. Fajertag & P. Pochet (Eds.), Social Pacts in Europe–New Dynamics (pp. 237–256). Brussels: ETUI.

- Peters, B. G., Pierre, J., & King, D. S. (2005). The politics of path dependency: Political conflict in historical institutionalism. The Journal of Politics, 67(4), 1275–1300.

- Phelan, S. (2007). The discourses of neoliberal hegemony: The case of the Irish Republic. Critical Discourse Studies, 4(1), 29–48.

- Quinlan, R. (2009). Geraghty’s des res and the house Jack ‘built’. The Independent. 8 November, 2009.

- Regan, A. (2012). the rise and fall of Irish social partnership. Dublin: Euro-Irish Public Policy.

- Regan, A. (2013). The impact of the Eurozone crisis on Irish social partnership: A political economy analysis. Unpublished paper. International Labour Organization. Working paper No. 49.

- Regan, A. (2016). Post-crisis social dialogue: good practices in the EU-28. The case of Ireland. Unpublished paper. International Labour Office.

- Regan, A. (2017). Rethinking social pacts in Europe: Prime ministerial power in Ireland and Italy. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 23(2), 117–133.

- Robbins, G., & Lapsley, I. (2014). The success story of the Eurozone crisis? Ireland’s austerity measures. Public Money & Management, 34(2), 91–98.

- Roche, W. K. (2009). Social partnership: From Lemass to Cowen. The Economic and Social Review, 40(2), 183.

- Rogers, S. (2010). Social partnership did enormous damage, says Lenihan. The Irish Examiner.15 December, 2010.

- Ross, S., & Webb, N. (2010). Wasters. Dublin: Penguin Ireland.

- RTE. (2009). Isme calls for the end of social partnership. RTE. 13 November, 2009.

- Rueschemeyer, D. (2006). Why and how ideas matter. In R. E. Goodin & C. Tilly (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of contextual political analysis (pp. 227–251). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schmidt, V. A. (2000). Values and discourse in the politics of adjustment. In F. W. Scharpf & V. A. Schmidt (Eds.), Welfare and work in the open economy Volume I: From vulnerability to competitiveness (pp. 229–309). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schmidt, V. A. (2002). The futures of European capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schmidt, V. A. (2008). Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Annual Review of Political Science, 11, 303–326.

- Schmidt, V. A. (2010). Taking ideas and discourse seriously: Explaining change through discursive institutionalism as the fourth new institutionalism. European Political Science Review, 2(1), 1–25.

- Schmidt, V. (2014). Speaking to the markets or to the people? A discursive institutionalist analysis of the EU’s sovereign debt crisis. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations, 16(1), 188–209.

- Teague, P., & Donaghey, J. (2009). Social partnership and democratic legitimacy in Ireland. New Political Economy, 14(1), 49–69.