ABSTRACT

This research note has two functions. It first sets the scene for this special issue using the 2020 Irish National Election Study (INES), which comprises several discrete data sets. The note also reports on findings from one part of the INES – an online poll of voters of polling day, which included a battery of questions related to attitudes and behaviours relevant to national politics. The note provides an empirical analysis of the vote choice in this election. Rather than taking a theory-testing approach, we use a more data-driven strategy and identify the key variables in the data set that are of relevance to an understanding of vote choice. Our findings support the views of other recent commentaries of Irish elections that Irish electoral politics is undergoing major transformation. The new electoral politics that is emerging is personified by a clear left vs. right divide in which strongly held ideological positions separate the voters of the main parties.

Introduction

In contemporary democracies there is a long-standing tradition of a large, national election survey at the time of, or shortly after, a parliamentary election. The British Election Survey, the American National Election Survey, or the German Election Data Project are some of the more well-known examples. In Ireland, the Irish political science community has organised the Irish National Election Study (INES) since 2002, but it has struggled to attract sufficient public funding to maintain consistency over the years, resulting in the political science departments arranging their own funding to ensure the series continues.

The 2020 INES, the focus of this Special Issue,Footnote1 comprises several discrete elements. University College Dublin in cooperation with Ireland Thinks carried out an online poll on the day of the election.Footnote2 At the same time, researchers at the University of Limerick developed a voter advice application online, which enabled them to collect significant data on respondents’ political attitudes, and colleagues at Dublin City University collected information on media and social media during the campaign leading up to the election. These sources together provide a wealth of information on voter behaviour and media coverage in the 2020 Dáil election.Footnote3

This research note makes a first foray into the UCD/Ireland Thinks data set (the INES 1), setting the scene for the papers that follow in this special issue by providing a general overview of the main drivers of the vote in 2020. We carry out an empirical analysis of vote choice in this election, examining what it is that differentiates voters for each of the main political parties. Rather than adopting a theory-testing approach, we use a more data-driven strategy, identifying the key variables in the data set that are of relevance to understanding vote choice in 2020. The note is structured as follows. We start by briefly setting the context of the extraordinary election outcome in 2020. We then present the logic of the machine learning approach being adopted here, which works on the basis of using a host of independent variables to predict outcomes. We apply this technique to the 2020 data set, which indicates several interesting trends, among them: an emerging left vs. right divide in electoral politics in which strongly held ideological positions trump parochial, candidate-centred concerns. The note concludes with a brief review of the papers that follow in the rest of this special issue.

The context of the 2020 Irish elections

In these times of electoral change it is commonplace to talk of the outcome of an election as being like no other, and certainly the 2020 Irish election did not disappoint in that regard. This was the election in which Fine Gael expected to be rewarded for its stewardship of the economy, having taken the economy out of recession and supposedly into another period of prosperity. This was the election in which Fianna Fáil (buoyed in particular by early campaign opinion poll bumps) expected to continue its path to renewal almost a decade after its 2011 electoral meltdown. This was the election in which Sinn Féin – smarting from poor mid-term electoral trends – was targeting steady state, or at best slight gains, but nothing too dramatic. All such predictions were to be proven wrong. This proved to be the best election ever for Sinn Féin, the worst election for Fine Gael since the 1940s, and for Fianna Fáil (apart from its 2011 meltdown) it was its second worst electoral outcome ever. But for a cautious candidate strategy of not running many candidates Sinn Féin would have been the largest party in the Dáil. The two mainstream parties were left clinging on to power by their finger-tips only on the basis of agreeing to the (previously unthinkable) proposal of forming a coalition government with rotating Taoisigh.

The titles of the accounts of this election outcome that have been published so far provide a useful summary of just how seismic it was: ‘the end of an era’ (Gallagher, Marsh, & Reidy, Citation2021); ‘two-and-a-half party system no more’ (Field, Citation2020); ‘change gradually then all at once’ (Little, Citation2021). This was an election that produced a number of stand-out results: the second lowest electoral turnout among post-war Irish elections; the second most volatile election in the history of the state; the worst ever electoral outcome by the established parties; and a further fractionalisation of the party system (at least as measured by the effective number of legislative parties). The 2011 INES referred to that election as ‘a conservative revolution’ (Marsh, Farrell, & McElroy, Citation2017). On this occasion, the revolution we witnessed in 2020 was far from conservative. If this was, indeed, ‘the end of an era’, then it is timely to speculate over what new era is in the process of emerging.

Machine learning and election studies

The typical approach to studying patterns in electoral behaviour is to formulate a set of hypotheses with expected relationship between key variables. For example, we might hypothesise that the lower social classes are more likely to vote for parties on the left, or that more religious voters are more likely to vote for the traditional government parties in Ireland. Hypotheses such as these are based on patterns that are regularly seen in a range of election surveys across the world of democracies, or they are based on careful theoretical derivations from basic assumptions. When state of the art methods are applied, these hypotheses are typically tested using multiple regression or some experimental design to attempt to properly control for potential confounding factors.

Following earlier trends in economics, political science methodology has seen an increasing focus on causal inference. Where existing statistical methods, such as factor analysis or multidimensional scaling, would be developed from the perspective of summarising high-dimensional multivariate data or to develop refined measurements of social science concepts, the focus is now on precise estimates of causal effects. By approximating experimental research designs as closely as possible even when the data are observational, these newer methods seek to address confounding effects (Angrist & Pischke, Citation2008; Morgan & Winship, Citation2007). Furthermore, there is a more consistent focus on assessing the level of statistical uncertainty in any quantities of interest (King, Tomz, & Wittenberg, Citation2000), which is often lacking in conventional multivariate techniques.

There are very good reasons for this emphasis on theory-driven hypotheses on explanatory factors that are evaluated with careful causal inference designs, but it does have its limitations. The first is that it has de-emphasised careful measurement in favour of causal inference. Without careful measurement, that tries to capture sometimes difficult to observe underlying latent factors, looking at relationships between key variables can be a tricky endeavour. Secondly, while the deductive approach is the most appropriate for careful evaluation of causal effects, it does limit the ability of the researcher to discover surprising patterns in the data. While discovery can take place, for example through creative thought or innovative connections across academic disciplines, another method is to ‘let the data speak’, which is our focus here.

Our discussion so far has referenced two of the three types of theory outlined by Gerring (Citation2001), namely description and explanation. The third is prediction. In statistical research prediction is at the core of machine learning and data science (Hastie, Tibshirani, & Friedman, Citation2009), where the aim is often to use algorithms to predict customer behaviour, identify faulty products, classify behaviour in public spaces, and so on. When prediction, rather than causal inference, is the key focus, concerns about confounding (which is at the heart of causal inference) move to the background and identifying patterns in the data becomes key. We can attempt to find latent structure in the data (unsupervised learning) or use variables in the data to classify or predict specific outcome variables (supervised learning). The former is closely aligned with – and often use the same methods as – the older tradition in quantitative political science that was more focused on measurement, while the latter is more closely aligned with contemporary methods in political science, but without any regard for potential confounding.

In the analysis that follows we will take a slightly different perspective and try to ‘let the data speak’, without any clear prior expectations about what we should find. We apply two closely related methods from the supervised machine learning literature, the classification tree and the random forest algorithm.

The classification tree is a statistical method whereby a set of observations in a high-dimensional space, defined by a range of variables, is iteratively split in two, such that the two groups are maximally different on the outcome variable. For example, if we want to explain turnout in an election, the first variable the algorithm might split the data on is by age, separating younger from older voters based on some threshold age, if this creates the greatest difference between the two groups in terms of the likelihood to vote. In the second step, the algorithm will then either split this group of younger voters, or the older ones, based on some other variable, again to get the maximum difference between the two subgroups. This algorithm implicitly allows for complicated interactions between variables and is naturally well suited for both categorical and numerical variables.

One downside of the classification tree algorithm is that the selection of the variable to branch on can be strongly driven by the level of variation in the variable. Variables with a higher level of variance are more likely to be selected as the variable to split the data on. A further limitation is that the tree can easily be too fine-tuned to a specific data set, emphasising patterns that are not generalisable. It thus can suffer from overfitting. The random forest addresses these concerns by running a large number of tree algorithms on the same data, but using bootstrapped samples to avoid overfitting,Footnote4 and each iteration leaving out a small subset of variables to avoid overreliance on variables with high variance. The benefit is that it is more robust, though there is a downside that it is not as straightforward to visualise the model as with a tree analysis.

Predicting vote choice in the 2020 elections

This special issue includes a range of articles that carefully analyse specific theoretical arguments using the INES 2020 data and related data sets. As outlined above, in this introductory note we will take a different perspective and focus on predictive algorithms, with first preference vote as the outcome variable.Footnote5 The intention is to seek to identify some unexpected patterns that go beyond the typical explanations of Irish electoral behaviour that might guide future theoretical and empirical investigations into these patterns. Of course, any future theories based on these findings could not validly be tested on this same data set, but they could be investigated in future Irish, or international election studies.

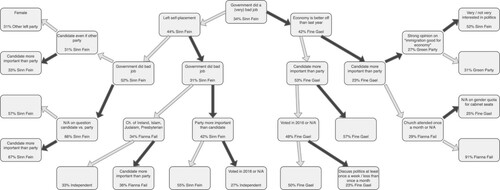

The first model we investigate is the tree model. We use nearly all the variables in the INES 1 data as potential explanatory factors.Footnote6 provides a schematic overview of the findings of our analysis. We see that the first variable on which we can split the sample to maximise the difference in predicted vote choice is government satisfaction, capturing the government versus opposition dynamic. Those who considered the performance of the government poor on average were more likely to vote Sinn Féin, while those who were satisfied or neutral towards the government were more likely to vote Fine Gael. And this split is visible throughout the diagram: on the left we find primarily opposition parties, on the right primarily government parties.

Figure 1. Tree diagram explaining first preference vote choice. The ‘yes’ branch in light grey, the ‘no’ branch in black. Each box shows the variable on which there is a branch following, the party which has the highest first preference vote in this branch, and the percentage that have this party as first preference.

On the left, we subsequently find that left-right self-placement is the next variable to split the sample on, with those on the left indicating a stronger likelihood of voting Sinn Féin than those on the right. This is in line with the findings from the 2016 election study by Cunningham and Elkink (Citation2018) that the left-right dimension matters in separating parties on the left in Ireland, but not those on the right. On the right, the next variable of importance is a further evaluation of government performance, focusing specifically on the economy. Those who thought the economy was better off than the previous year were much more likely to vote Fine Gael than those who do not, which was consistent with that party’s messaging in this election.

Strikingly, on both sides, the next variables that start to play a role are related to whether a voter primarily votes for a particular party or for a particular candidate. Among those who disapproved of the government and who were on the left of the ideological spectrum, most ended up voting for Sinn Féin, with the only category where other left parties dominated Sinn Féin being those voters who thought the government performed badly but not very badly, and who indicated that would vote for their candidate even if this candidate were standing for a different party. Among those more on the right, who thought the government performed very badly, and who thought the party is more important than the candidate, most voted for Sinn Féin. If they did not consider the party more important, they were more likely to vote for an independent candidate than for Sinn Féin. Among those more on the right who had a more moderately negative evaluation of the government performance, church denomination became relevant with Catholics voting Fianna Fáil and others voting independent.

Those who approved of the government performance and thought that the economy had improved were most likely to vote Fine Gael. The candidate versus party question played a small role in exactly how likely, but no other party became more dominant than Fine Gael for this cohort of voters. Among those who approved of the government, but thought that the economy disimproved, those who considered the candidate more important than the party split on church attendance. Those who go to church about once a month voted Fianna Fáil, while those who go more or less often were more likely to vote Fine Gael. For those in this group who considered the party more important than the candidate, those with a strong opinion on either extreme on the statement that immigration is good for the economy, were more likely to vote for the Green Party, while those without a strong opinion were more likely to vote Sinn Féin.

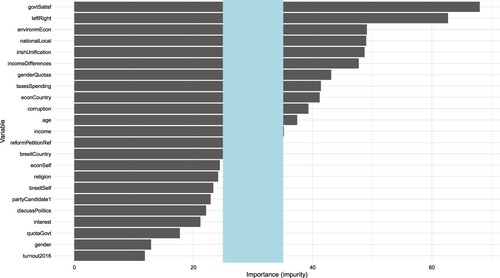

As we discussed above, while the tree analysis allows for a detailed interpretation of the relationships and interactions between the variables in predicting vote choice, the downside is that it is too strongly influenced by a bias in favour of explanatory variables with higher variance and can be strongly driven by a few outlier variables in the data. To address this, we can run a random forest analysis. Because in the random forest analysis, we obtain many trees, it becomes difficult to think of the ‘average tree’. Instead, we can look at how often particular variables play a role in splitting the sample early in the tree model. Therefore, we can think of the average ‘importance’ of a variable across trees in the random forest. provides a visualisation of the relative importance of variables, focusing on the variables that are most and least important, and leaving out the variables in the middle.

Figure 2. Importance of explanatory variables in a random forest analysis to explain first preference vote choice, including only the most and least important variables. Greyed out area corresponds to the importance values of the variables that were left out.

In line with the tree analysis, we find that the first variables that are important in predicting the vote choice are government satisfaction and left-right self-placement, and by a wide margin. Strikingly, however, the relevance of party versus candidate fully disappears when we look at these trees across bootstrapped samples. Religion and church attendance similarly become far less relevant. These tree analysis results were clearly driven by relatively few observations in the sample, which are not present in all bootstrapped samples, reducing the importance of these variables. Instead, all more general ideological variables become relevant for the vote prediction – whether one prioritises the economy over the natural environment; whether one thinks representatives should focus primarily on local or on national issues; whether one is in favour or against Irish unification; whether one thinks the government should try to reduce income differences or not; whether one considers gender quotas a good idea or not; and so on. All these attitudinal variables are key drivers of vote choice.

Another striking finding is that neither gender nor political interest and engagement appear to matter much when predicting vote choice. Also more utilitarian considerations, such as the expected impact of Brexit on oneself or the evaluation of one’s own financial situation in the previous period do not figure much in this prediction. Altogether this suggests that, aside from a government-opposition dynamic, the vote in Irish elections is much more ideologically driven than previous accounts might have suggested (see also Cunningham & Elkink, Citation2018; Muller and Regan, this issue; Cunningham & Marsh, Citation2021). This speaks to the argument that many of the old shibboleths that underlay the notion of Irish electoral politics as sui generis no longer apply: Irish electoral politics can no longer be described as ‘politics with social bases’ and lacking programmatic differences (Carty, Citation1981; Urwin & Eliassen, Citation1975; Whyte, Citation1974), or driven by localism (Carty, Citation1981; Chubb, Citation1957; Marsh, Citation2007) or family traditions (Carty, Citation1981; Gallagher & Marsh, Citation2002; Sinnott, Citation1995).

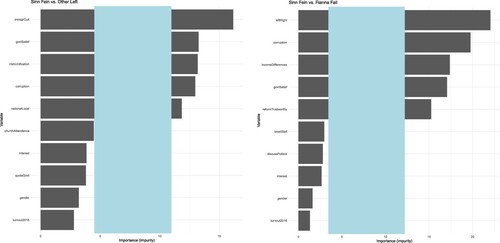

While the analysis thus far focuses on the multinomial question of vote prediction among all parties, the 2020 election stood out in particular for the strong performance of Sinn Féin: as Cunningham and Marsh (Citation2021) note this was ‘the Sinn Féin election’. As a final analysis, we look at two specific pairs of parties, in each instance excluding from the sample any voters who did not vote for either of these two parties. The results are presented in , where on the left we contrast Sinn Féin with the other left partiesFootnote7 and on the right Sinn Féin with Fianna Fáil, the main opposition party on the right.Footnote8

Figure 3. Importance of explanatory variables in a random forest analysis to explain first preference vote choice, including only the most and least important variables, contrasting Sinn Fein to Fianna Fail voters and other left parties. Greyed out area corresponds to the importance values of the variables that were left out.

When it comes to the competition between Sinn Féin and other left parties, the strongest factor is the view on whether immigration is good for Irish culture. Cross-tabulation shows that those who strongly disagree with the idea that immigration ‘generally harms’ Irish culture are pretty evenly split between Sinn Féin and other left parties, while those who are more sympathetic with this idea are considerably more likely to vote for Sinn Féin. Attitudes towards Irish unification are another key driver for this separation, but not in the monotonous fashion one would have expected. At both extremes of this scale, support for Sinn Féin is higher; other left parties gain more support among those who are moderately in favour of abandoning the idea of a united Ireland. Finally, those who perceive high levels of corruption in Ireland are more likely to opt for Sinn Féin instead of other left parties. The trends on attitudes to corruption lend support to the argument that Sinn Féin is attracting a left-populist vote (Muller and Regan, this issue), while those on immigration are suggestive of an as yet untapped resource on the right-extreme (e.g. Costello, Citation2017; also Costello, this issue).

The competition between Sinn Féin and Fianna Fáil is primarily an ideological one, with the main driver of the vote separation between the two parties being the left-right self-placement of the voter, and opinions on income driving a further dividing factor. Again, perceived levels of corruption is also a key driver in separating these voters, with Sinn Féin voters perceiving high levels of corruption and Fianna Fáil voters seeing very little. Similarly, there is a differentiation in terms of how trustworthy voters consider TDs to be. These trends might give some pause for thought to senior Sinn Féin figures about recent moves by some in Fianna Fáil to promote a closer relationship with their party.

These tree and forest analyses have not produced any startling new findings, but they do support the general consensus that electoral politics in Ireland is in a process of transition. The remnants of the old model – defined by the predominance of the two civil war parties (Little & Farrell, Citation2021) – is in fast decline as Sinn Féin emerges as the major ‘new’ player. With this comes clear programmatic differences between a bloc of voters on the right centred on Fine Gael and a bloc on the left centred on Sinn Féin. And parish pump sensibilities are increasingly being replaced by strongly held ideological positioning. This all speaks to a party system that would fit comfortably in any comparative description of electoral politics today: the notion of Irish party politics as ‘unique’ is now dead and gone.

An interesting sub-theme emerges from the forest analysis of the Sinn Féin support base, which includes voters who express anti-immigration views and who believe that politics in Ireland is corrupt – adding credence to previous studies (e.g. O’Malley, Citation2008), which suggest that at least some of that party’s support base comprises individuals ripe for the picking by right-wing populists.

Empirical investigations using the 2020 INES

The purpose of this special issue is to demonstrate how the wealth of information provided by an election study can be used to understand electoral outcomes in this extraordinary election and the state of representative democracy in Ireland today. Our agenda is to showcase a mix of different types of analyses, starting with a number of articles seeking in one way or another to explain the vote, and then several articles that broaden out the perspective, using the INES data to consider other themes in the study of contemporary Irish public opinion.

We begin with five articles focused specifically on the election itself, starting with Michael Lewis-Beck and Stephen Quinlan’s examination of economic voting in 2020. The puzzle they seek to answer is why the incumbent government led by Fine Gael failed to reap the electoral dividends of a buoyant economy that economic voting models would generally expect. Their analysis shows that while some voters were, indeed, feeling the economic upturn, many were not. Voter attitudes to the economy and their position in it also feature prominently in our second paper by Stefan Müller and Aidan Regan, which shows how in 2020 there was a distinct shift left by Irish voters (whether measured by self-location on the left-right dimension, or policy preferences on spending and dealing with inequality), the main beneficiary of which was Sinn Féin. That party clearly benefited from the mood swing in the Irish electorate, suggesting a higher degree of congruence between it and its voters than was the case for the other parties – the theme of our third article, by Rory Costello. Using data gathered from Which Candidate voting advice applications in the 2020 election and also the 2019 European Parliament election, his analysis reports higher levels of congruence for those parties (like Sinn Féin and the Greens) that are closely linked to particular policy areas (Irish unity, the environment), whereas the more catch-all nature of the two large mainstream parties results in lower levels of voter congruence. Echoing his findings from an earlier study (Costello, Citation2017), Costello also finds evidence of clusters of voters (older, less educated and rural voters) whose views are being less well represented by existing political parties.

Our fourth article by Lisa Keenan and Mary Brennan examines whether there was a bias against women candidates in the 2020 election. This was the second election to use gender quotas, and the lack of significant improvement in electoral outcomes for women candidates was noteworthy: the proportion of women TDs hardly increased at all compared to 2016. Despite this, Keenan and Brennan’s analysis of the trends using the 2020 INES finds no evidence to suggest that a voter bias existed against women candidates. In our final paper devoted to the 2020 election the focus shifts to an analysis by Kirsty Park and Jane Suiter of newspaper coverage of the parties and their social media (Facebook) communication strategies. According to their evidence, the media coverage stressed (and therefore perhaps in part fed) the atmosphere of electoral change, a theme that was also emphasised by Fianna Fáil and Sinn Féin, the latter adopting a ‘populist communication style’.

Our remaining two articles use the 2020 INES to broaden our perspective, by examining contemporary voter attitudes towards current debates over political and institutional reform. In his article, Luke Field examines the reasons why voters rejected local referendums on the proposed introduction of elected majors in two counties a year earlier (in a third county the vote passed), finding some evidence to suggest that partisan dynamics was a factor in the outcome. Our final article by Walsh and Elkink investigates the factors that drive support for deliberative citizens’ assemblies, finding that distrust leads to support for any political reform, while education and political interest are the main drivers of support for citizens’ assemblies in particular.

Together, this collection of articles demonstrate the importance of proper (and properly funded) electoral research and the wealth of insights we can obtain into the mind-set of the Irish electorate – the citizens that are at the heart of the democratic system.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Johan A. Elkink

Johan A. Elkink is Associate Professor in Research Methods for the Social Sciences at University College Dublin. His work spans computational modelling, spatial econometrics, and statistical network analysis, applied to voting behaviour, democratization, and comparative politics generally. His work has appeared in the Journal of Politics, European Journal of Political Research, Comparative Political Studies, and Oxford University Press, among other academic outlets.

Professor David M. Farrell, MRIA, holds the Chair of Politics at UCD. A specialist in the study of representative politics, his current work is focused on deliberative mini-publics. A co-editor of the recently published Oxford Handbook of Irish Politics (OUP, 2021), his latest co-authored book is Deliberative Mini-Publics: Core Design Features (Bristol University Press, 2021).

Notes

1 We are grateful to the Journal’s editors for their guidance and support, and to the referees of this paper and all the papers in this Special Issue.

2 We thank UCD Research, the UCD College of Social Sciences and Law, and the UCD School of Politics and International Relations who generously provided funding to support the gathering of survey data for the 2020 INES, which are being used in this note and in other papers in this Special Issue (Elkink & Farrell, Citation2020).

3 Many of these data sets have been uploaded for free access at the Harvard Dataverse (Costello, Citation2020; Elkink & Farrell, Citation2020). In addition the Harvard Dataverse also includes freely accessible data from the UCD-RTÉ-TG4-Irish Times-Ipsos MRBI Exit Poll of the 2020 election (Elkink & Farrell, Citation2020a). There is in addition a separate data set that was funded by Trinity College Dublin and University College Cork (cf. Cunningham & Marsh, Citation2021).

4 A bootstrapped sample is a subset of an existing sample, randomly selected but with replacement, of the same size as the original sample. This means that every bootstrapped sample consists of individuals from the original sample, but each time some observations are repeated, while others are left out. It can be shown that, on average, bootstrapped samples relate to the original sample in a similar fashion as the original sample relates to the overall population, such that the distribution of a statistic across bootstrapped samples is similar to the distribution of the same statistic across samples taken from the population. We can therefore use bootstrapped samples to assess uncertainty in statistics we calculate - including the uncertainty around the shape of our classification trees.

5 Note that for all models, the Labour Party, Social Democrats, Solidarity/PBP, and the Workers’ Party have been classified as ‘Other Left’, while Aontu, the National Party, Renua, Irish Freedom and the Irish Democratic Party have been classified as ‘Other Right’.

6 The variables included are: gender, age, education, churchAttendance, religion, employment, income, whenDecide, partyCandidate1, partyCandidate2, turnout2016, interest, discussPolitics, leftRight, govtSatisf, econCountry, econSelf, brexitCountry, brexitSelf, equalEthnic, equalWomen, equalGays, genderQuotas, quotaGovt, irishUnification, taxesSpending, incomeDifferences, environmEcon, nationalLocal, particAssembly, reformMayors, reformExperts, reformFewerTDs, reformPetitionRef, reformTrustworthy, reformAssemblies, immigrEcon, immigrCult, and corruption. See the codebook of the INES 1 data for a description of each of these variables (Elkink & Farrell, Citation2020).

7 For the purposes of this exercise, ‘other left parties’ are being treated as one party. See Footnote 5 for details on which parties are included under this category.

8 When a similar comparison is made between Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, the main drivers are government satisfaction and the evaluation of the economy, i.e. this is a purely government-opposition dynamic. An analysis of the next general election, when both parties have been in government, will be particularly interesting to help understand the basis of the separate supports for these parties, where the lack of programmatic distinguishability between them has been the main ground for considering the Irish party system as less ideological than elsewhere (Carty, Citation1981; Lutz, Citation2003).

References

- Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2008). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist's companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Carty, R. K. (1981). Electoral politics in Ireland: Party and parish pump. Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Chubb, B. (1957). The independent member in Ireland. Political Studies, 5, 131–139.

- Costello, R. (2017). The ideological space in Irish politics: Comparing voters and parties. Irish Political Studies, 32, 404–431.

- Costello, R. (2020). 2020 which candidate data. Harvard Dataverse, V1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OEYRN7

- Cunningham, K., & Elkink, J. A. (2018). Ideological dimensions in the 2016 elections. In M. Marsh, D. M. Farrell, & T. Reidy (Eds.), The post-crisis Irish voter (pp. 33–62). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Cunningham, K., & Marsh, M. (2021). Voting behaviour: The Sinn Féin election. In M. Gallagher, M. Marsh, & T. Reidy (Eds.), How Ireland voted 2020: The end of an era (pp. 219–254). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Elkink, J., & Farrell, D. (2020). 2020 UCD Online Election Poll (INES 1). Harvard Dataverse, V4. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/E6TAVY

- Elkink, J., & Farrell, D. (2020a). 2020 UCD-RTE-TG4-Irish Times-Ipsos MRBI Exit Poll (INES 2). Harvard Dataverse, V1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HJIB3S

- Field, L. (2020). Irish general election 2020: Two-and-a-half party system no more? Irish Political Studies, 35, 615–636.

- Gallagher, M., & Marsh, M. (2002). Days of blue loyalty: The politics of membership of the Fine Gael party. Dublin: PSAI Press.

- Gallagher, M., Marsh, M., & Reidy, T. (2021). How Ireland Voted 2020: The End of an Era. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gerring, J. (2001). Social science methodology: A criterial framework. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., & Friedman, J. (2009). The elements of statistical learning: Data mining, inference, and prediction. New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

- King, G., Tomz, M., & Wittenberg, J. (2000). Making the most of statistical analyses: Improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 347–361.

- Little, C. (2021). Change gradually, then all at once: The general election of February 2020 in the Republic of Ireland. West European Politics, 44, 714–723.

- Little, C., & Farrell, D. (2021). The party system: At a critical juncture. In D. Farrell & N. Hardiman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of Irish politics (pp. 521–538). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lutz, K. G. (2003). Irish party competition in the new millennium: Change or plus ça change? Irish Political Studies, 18(2), 40–59.

- Marsh, M. (2007). Candidates or parties? Objects of electoral choice in Ireland. Party Politics, 13(4), 500–527.

- Marsh, M., Farrell, D., & McElroy, G. (Eds.). (2017). A conservative revolution? Electoral change in twenty-first-century Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Morgan, S. L., & Winship, C. (2007). Counterfactuals and causal inference. Methods and principles for social research. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- O’Malley, E. (2008). Why is there no Radical Right Party in Ireland? West European Politics, 31(5), 960–977.

- Sinnott, R. (1995). Irish voters decide: Voting behaviour in elections and referendums since 1918. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Urwin, D. W., & Eliassen, K. A. (1975). In search of a continent: The quest of comparative European politics. European Journal of Political Research, 3(1), 85–113.

- Whyte, J. (1974). Ireland: Politics without social bases. In R. Rose (Ed.), Electoral behaviour: A comparative handbook (pp. 619–651). New York: The Free Press.