?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Arguably, the most fundamental question one can ask about a party system is whether it is bipolar or not. Based on theoretical conjectures and on tendencies one observed during the 1990s and early 2000s, as well as reflecting the position of the academic community at the time (e.g. [Bale, T. (2003). Cinderella and Her ugly sisters: The mainstream and extreme right in Europe's bipolarising party systems. West European Politics, 26(3), 67–90; Müller, W., & Fallend, F. (2004). Changing patterns of party competition in Austria: From multipolar to bipolar system. West European Politics, 27(5), 801–835]), Peter Mair had a clear prediction: the future of party politics would be bipolar. Using the Who Governs Europe dataset [Casal Bértoa, F., & Enyedi, Z. (2021a). Party system closure: Party alliances, government alternatives, and democracy in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press], the article examines the validity of Mair's predictions. Notwithstanding certain exceptions (e.g. Bulgaria, Luxembourg, Serbia), the article demonstrates that the tendency towards increasingly bipolarised party politics has failed to materialise. Next to the description of empirical patterns the article provides suggestions on how to improve our conceptual apparatus of party system analysis.

Introduction

In February 2020, Sinn Féin (SF) won a plurality of the first preference votes for the first time in the history of Irish democracy (Little, Citation2021), turning SF into the third pole of an otherwise two-bloc party system. The subsequent governing formula, a coalition between Fianna Fáil (FF), Fine Gael (FG) and the Green Party (GP), was unprecedented, bringing together the arch-enemies of Irish politics and consolidating the pattern of partial government alternation in a country where wholesale alternation has been the norm.

In some sense these developments were very much in line with Peter Mair's work and with the predictions that can be derived from his theories concerning the decline of traditional party loyalties and the increasing promiscuity of parties in coalition making (Mair, Citation2013). The trigger for this train of thought originated in Irish politics too: commenting on the then surprising 1989 FF-Progressive Democrats coalition (surprising because Fianna Fáil used to govern alone), he envisioned a trend towards less structure and ideological discipline and more volatility in European party politics (Mair, Citation2006, p. 67).

But the current development challenges another suggestion of Mair, the one on the bipolarisation of party politics. If, like in today's Ireland, the composition of governments is no longer predictable, if most parties can end up in coalition with most other parties, and if wholesale alternation is replaced by partial alternation, then party politics is no longer structured in a bipolar way. The most obvious consequence of the shift towards multipolarity is that it increases the complexity of government formation. Furthermore, it can contribute to cabinet instability, it may undermine the partisan accountability of governments, and it can push party systems towards de-institutionalisation. At the very same time, it allows for a more nuanced representation of political alternatives than a simple dichotomous configuration.

If the departure from bipolarity were an Irish phenomenon, a case study would be necessary to identify its causes and consequences. But a similar trend is visible in most parts of Europe. Besides, we also need to open our analytic lens because Mair's prediction referred to the whole continent. The issue, therefore, demands the revisiting of the theoretical arguments and a systematic analysis of all European cases.

The article is structured in five sections. First, we clarify the notion of bipolarisation. Then we reconstruct the theoretical argument behind Mair's expectation for a bipolar tendency in European politics and discuss the state of European party systems during the mid-2000s, that is, when Mair wrote the most relevant piece on the subject. Section two presents the dataset that will be used to test the extent to which Mair's predictions were accurate. Building on Casal Bértoa and Enyedi (Citation2021a), an analysis of the patterns of competition in Europe's currently democratic party systems and the level of bipolarisation will be presented in section three. Section four reviews the factors considered responsible for the failure of the bipolarisation thesis. The article concludes with a summary of the main findings and a reflection on the future of inter-party competition in Europe.

Bipolarity: what is it?

Arguably, the most fundamental question one can ask about a party system is whether it is bipolar or not. There exists a large body of literature showing that when it comes to ideological polarisation, government-building, accountability, and a host of other relevant political phenomena (Kam, Bertelli, & Held, Citation2020), bipolar systems have special characteristics. For example, in our most recent book (Casal Bértoa & Enyedi, Citation2021a, pp. 122–124), we found that bipolarity is significantly and positively related to the party system closure and stability.

In Mair's work the significance of bipolarity lay in the fact that the competition of two camps is necessarily focused on the choice of alternative governments, while more complex, multiplayer configurations emphasises on the expressive–ideological or subcultural–functions of parties. In the first case, politicians compete in terms of their potential to manage the country's affairs as efficiently as possible, while in the latter instance the stakes of elections are what represent the values and interests of particular groups of voters in the most authentic fashion.

Mair had a clear prediction concerning the ratio of bipolar vs. multipolar systems. Based on theoretical conjectures and on tendencies he observed during the 1990s and early 2000s, he expected the future to be bipolar.Footnote1 Specifically, he wrote in Crotty and Katz's Handbook of Party Politics: ‘[…] the party systems of the future are more and more likely to reflect the type of bipolar competition that has long been characteristic of the French Fifth Republic (Citation2006, p. 70)’. The idea was later reiterated in ‘The Challenge of Party Government’, a piece published in West European Politics (WEP), where he spoke about a ‘growing evidence of bipolarity’ (Citation2008, p. 228).

Before we investigate the justification and the validity of this claim, we need to clarify what bipolarisation means. In our understanding (Casal Bértoa & Enyedi, Citation2021a; Mair, Citation2006; Sartori, Citation1976) those party systems can be considered bipolar that are dominated by two alternating parties or by two alternating alliances (or blocs) of parties. The bipolar configuration is possible and unequivocal if the boundaries of the competing alliances are well established and if there are no relevant political parties moving between the alliances. Such a pattern is more likely to materialise if all the parties that are present in the system can play a role in government-building. The existence of significant pariah parties, or parties that refuse to participate in governing, leads to a shrinkage of the pool of ‘coalitionable’ actors, decreasing the likelihood of any bloc reaching the threshold needed to form a government.Footnote2

Next to the weakness of swinger and pariah parties, the third crucial facilitating condition of bipolarity is the lack of cleavages crosscutting the government opposition divide. As a result, the opposition parties do not see themselves to be closer to any of the government parties than to their fellow opposition parties. Consequently, when the government is defeated, all opposition parties are ready, in principle, to cooperate in the new government. The competition between government and opposition, on the other hand, is zero sum. The voters pass a verdict about the identity of the new government. The result is the periodic wholesale alternation of governments.

Although according to some definitions (see Bartolini, Chiaramonte, & D’Alimonte, Citation2004, p. 2), only those systems can be considered to be bipolar in which one of the blocs can obtain the absolute majority of seats, this is an unnecessarily restrictive approach, as in many countries parties can run governments with fewer seats.

Bipolarity also implies that while individual parties may come and go, the principal alternatives do not change from election to election. Mair predicted the coexistence of ‘unsettled range of partisan or semi-partisan components’ with ‘core coalitional continuity’ (Mair, Citation2006, p. 71). Such a configuration would imply that the newly emerging parties do not create a new pole but rather tend to join one of the existing blocs.Footnote3

Peter Mair and the future of European politics

Why did Mair think in the mid-2000s that bipolarisation will prevail? This prediction was based on his observations, according to which there is a decline in the distinct identity of individual parties due to the fact that specific political subcultures are losing their relevance and ideology is becoming less important. Party strategies are determined by professional politicians primarily interested in governing. The media focuses on leaders instead of programmes. Citizens consider performance as an important criterion for choice, the strength of party loyalty is waning. All these factors point towards the increasing relevance of the ability to govern, which can be demonstrated only by forces that command significant support.

Mair's expectations were grounded (largely implicitly) in a functionalist logic. According to this logic, elections and parties are supposed to fulfil some social function. If they cannot have an expressive function, they should be about providing choice for government selection. In terms of the latter function, parties are more important than ever. The government-deciding role of elections is strengthened by the negative attitude of citizens and the media towards post-election negotiations between party elites.

This new character of elections was supposed to be enhanced further by the decline of the anti-democratic alternatives, primarily Communism and Fascism, providing room for wide centre-left vs. centre-right alliances that can credibly compete for the government. The stakes of the elections decreased because the two competing alternatives tend to overlap in programmatic terms. But the competition about who should fill public offices is as intense as ever, and the power of the voters to determine the composition of the government is also significant.

Mair's perceptions were strongly shaped by the transformation of the Italian party system in the 1990s. The co-operation of Rifondazione Comunista with the moderate left, the rise of Forza Italia, Berlusconi's umbrella party, the decrease of the number of competitors in the Italian electoral districts, the rise of the winners’ share of the vote, the drop of the gap between the first- and second-placed candidates, and the decline in support of the third and lower candidates were recognised already in the mid-1990s as unmistakable signs of bipolarisation (D'alimonte & Bartolini, Citation1997).Footnote4 For the unity of the left under one pragmatic umbrella organisation, the development of the Italian Democratic party was a prominent example (Donovan, Citation2011).

During the 1990s and early 2000s similar phenomena were observed in various segments of European politics. Blair and Schröder symbolised the new pragmatism of the left.With the co-operation of communists and socialists on the left and with the collaboration of Gaullists, liberals and Christian-democrats on the right, France presented a clear-cut example of bipolarism. On a continental landscape, the newly emerged Greens were seen by Mair to be able to provide ‘the necessary extra weight to the left to allow for the possible emergence of a sustained bipolar pattern of competition’ (Citation2001, p. 111).

Next to Italy, Mair also emphasised the shift towards bipolarity in Austria and Germany and the earlier crystallisation of bipolar patterns in the Southern new democracies, Spain, Portugal, Malta and Greece. The conclusions were generalised for entire Europe:

even in those systems that are marked by quite pronounced party fragmentation, party competition is now more likely to mimic the two-party pattern through the creation of competing pre-electoral coalitions which tend to divide voters into two contingent political camps. During the 1950s and 1960s, for example, the majority of European polities changed governments by means of shifting and overlapping centrist coalitions and rarely if ever offered voters a choice of alternative governments. During the 1990s, by contrast, almost two-thirds of these older polities had experienced at least some two-party or two-bloc competition, usually involving wholesale alternation in government. (Citation2008, pp. 226–227)

Interestingly, the WEP article also speaks of ‘increased sharing of commitments’ (Citation2008, p. 216), citing the examples of Labour and Fine Gael in Ireland, and Labour and the Liberals in the Netherlands joining forces. But the overall tendency observed was one of increasing bipolarity. While most of the discussed cases were from Western Europe, Mair saw a similar tendency developing in the East too, concluding that ‘a number of the post-communist systems have also drifted towards more bipolar competition’ (Citation2008, p. 277). The tendency towards bipolarisation was presented as a virtual necessity because ‘[t]here are no longer any important pariah parties in competition’ (Citation2006, p. 69), and ‘anti-systemness has now become a thing of the past’ (Citation2006, p. 70).

Mair's conclusions were in synchrony with, and partly based on, the assessments of many other scholars. Bale, for example, also observed a tendency of bipolarisation, writing about a ‘shift away in places like the low countries, Italy, Austria and Germany, from a politics heavily influenced by centrist coalitions towards […] competitive bipolar pattern’ (Citation2003, p. 68). Formal coalitions developed between centre- and far-right in Italy, Austria and the Netherlands, and informal ones in Norway and Denmark. According to Bale, in many Western European countries ‘the centre-right, by including the far right either as a coalition partner or as a support party, has removed what was essentially an artificial constraint on the size of any right bloc in parliament’.

Finally, in a converging piece, Müller and Fallend (Citation2004) drew attention to the fact that in Austria after the 1999 elections, the government-opposition alignment was adjusted to the left-right divide, and the Liberal Forum, the party that could have complicated the co-operation among the opposition parties, dropped out of the parliament.According to the authors, these changes amounted to a bipolar turn in Austrian politics.

To summarise, Mair's perception of a bipolarising tendency reflected well the position of the academic community of his time. We now turn to examine whether these generalisations were accurate. In the first round we will rely on quantitative data reflecting the nature of government alternation, then we move to the individual cases and try to tease out the reasons behind the actual changes.

Government alternation

Bipolarity, as suggested above, implies periodic wholesale alternation. The ‘periods’ between alternations tend to vary, of course, as governments can win many elections in a row. Partial alternation, on the other hand, that is, the mixture of hitherto opposition and government parties contradicts bipolarity.Footnote5

To measure whether a particular year of European politics was characterised by partial alternations or by wholesale or no alternation, we use an index that was originally introduced by Mair (Citation2007; Casal Bértoa & Mair, Citation2012), and developed further by the present authors (Casal Bértoa & Enyedi, Citation2016, Citation2021a). The index is based on the sum of the differences in ministerial shares of parties in two consecutive governmentsFootnote6 (or ‘total net change’, an intermediate step in calculating volatility – cf. Pedersen, Citation1979). Party systems where the total net change is close to its minimum (0) or maximum (200) values (that is, complete change or no change at all) are in line with bipolar politics. Values closer to the midpoint of the scale indicate partial alternation. To scale the measure from 0 to 100 we subtract the volatility figure from 100. Consequently, the value for alternation is calculated as follows:

where Gt and Gt–1 are the sets of governing parties at times t and t –1, respectively and pi,t and pi,t–1 refer to the proportions of ministers that party i held in government t and t – 1.

We include into the analysis all European party systems that were democratic at the time of the publication of Mair's articles. We consider a country to have a democratic party system when (1) it has a score of ≥6 in the Polity IV index, (2) universal suffrage elections have been held at least once, and (3) governments are formed with (and rely on) parliamentary support, rather than on the exclusive will of the head of state (Casal Bértoa, Citation2021). In this context, countries, such as Russia or Turkey and Ukraine, where democracy collapsed in the late 2000s and mid-2010s, respectively, are not included. in the Appendix displays the final number of party systems included in our analyses (38), comprising more than 232 elections and 390 cases of government formation.

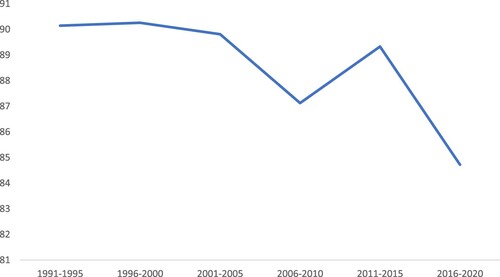

plots the alternation scores between 1991 and 2020, structured in five-year averages.Footnote7 The graph shows that when Mair wrote his assessment, the systems tended to be bipolar as the alternation score was over 90.Footnote8 But the graph also indicates that already at that time, a tendency in the opposite direction, towards partial alternation, was under way. This tendency proved not to be linear, but today's scores are lower (with 5.6 points)Footnote9 than at the turn of the century, and well beyond the European media (87.5) for the last two decades. To conclude, instead of bipolarisation, the changes in the alternation figures suggest a shift towards openness in government-building and towards instability in the conflict lines.

The future that never was

Turning to a qualitative assessment of the nature of party competition in individual systems (see Table A2 in the online Appendix), below we attempt to classify each case as either bipolar or multipolar, contrasting the mid-2000s, the time when Mair’s relevant articles were written, with the early 2020s.

At the beginning of the analysed period, two-thirds of the party systems in Europe could be classified as bipolar. Such systems were most common in the British Isles, the Mediterranean South, the Scandinavian North (Finland excluded), and parts of Central Europe.

In the United Kingdom, the plurality electoral systems and the class divide cemented the Labour-Conservative rivalry soon after the First World War. Five of the six Southern European states (Malta, Andorra, Greece, Spain and Portugal) also displayed from the very beginning of democratic politics the classic left-right opposition pitting Socialists against Conservative Liberals. Like in the United Kingdom, disproportional electoral rules,Footnote10 class cleavage and in the case of Malta and Spain (and to some extent also in the case of Portugal) the clericalism vs. anti-clericalism divide sustained the bipolar logic. Wholesale alternations were relatively frequent in Spain and Greece between the Socialists (PASOK and PSOE) and the Conservatives (New Democracy and the People's Party), while in the case of Andorra, governments tended to be dominated by the Liberals. In Portugal, where the electoral system was more proportional, a two-bloc party system developed with the Socialist Party on the left and the Social Democrats and the conservative People's Party on the right.Footnote11

With the exception of Andorra, all the listed cases continue to follow the logic of bipolarity (see Table B2 in the online Appendix), in spite of the increase in party system fragmentation. In Spain, the impact of the 2008 Great Recession led to the appearance of new parties, at the right and left of the political spectrum, but the system did not move towards multipolarity. Instead, the two-party system transformed into a two-bloc system. The blocs are led by the ‘traditional’ parties (i.e. PSOE and PP), but now in coalition (either government or parliamentary) with Unidas Podemos (an electoral coalition of the new populist radical-left Podemos and the Communist-led coalition called United Left) on the left and the liberal anti-nationalist Ciudadanos and, since 2019, populist radical-right Vox, itself a splinter from PP, on the right. The 2008 economic crisis also induced changes in the Greek party system, leading to the weakening of the traditional parties, the appearance of new ones, and, most importantly, the rise of the populist Coalition of the Radical-left (Syriza) in 2012. But the two-party structure re-emerged, after a period of turbulence, Syriza took over the place of PASOK.

In the Nordic countries, the opposition between the Social Democratic Party and the coalition of Conservatives, Liberals and Agrarians structured the logic of competition into a bipolar format early on. In Denmark, the Social-liberal Party, the Centre Democrats and the Christian Democrats could swing both ways in the earlier periods, but by the 1990s they integrated into a broad left-wing alliance, led by the Social-democrats. In Scandinavia, only the Icelandic Agrarians managed to preserve some of their third pole credentials.

In Eastern Europe, Albania and Hungary are the most bipolar cases. While the original conflict between post-Communist and anti-Communist forces has transformed into a conflict over cultural values and the nature of democratic institutions, the hostility between the two rival camps remained intact, limiting the possibilities for co-operation across the aisle. Between 2009 and 2016, Albania flirted with a two-and-a-half structure of competition when the Socialist Movement for Integration, a splinter from the Socialist Party (PSH), formed a coalition with the Democratic Party before colligating with PSH in 2013. However, two consecutive absolute majorities obtained by PSH in 2017 and 2021 brought the country back to a two-bloc configuration.

In each region, one can find countries that have always been closer to a multipolar configuration (see Table C2 in the online Appendix). Belgium, Cyprus, Czechia, Finland, Netherlands, San Marino, Slovenia and the three Baltic States are cases in point. LiechtensteinFootnote12 and Switzerland are special cases, best classified as ‘grand coalition’ party systems, but not following a bipolar pattern.Footnote13

In Bulgaria, Luxembourg and Serbia, the multipolar structure shifted towards bipolarity (see Table D2 in the online Appendix), in line with Mair's predictions but typically not because of the causal factors he had suggested. In Bulgaria, the opposition between Boyko Borisov's GERB and the Socialists, while in Serbia the conflict between Aleksandar Vučić's Serbian Progressive Party and the members of the earlier anti-Milošević camp divided the systems into two halves, although in the latter case, due to the overwhelming success of the Progressives, by the end of the period the system was bordering on unipolarity. The Luxembourgish party systems passed from a two-and-a-half pattern, where the Christian Social People's Party (CSV) acted as a hinge between the Socialist Worker's Party (LASP) on the left and the liberal Democratic Party (DP) on the right, to a two-bloc structure within which CSV is opposed by the coalition of LSAP, DP and the Greens. The rest of the countries, altogether 13, changed in the opposite direction. In the following, we consider each case on its own.

During the mid-2000s, the French pattern was a clear-cut example of bipolarity. The two-bloc pattern of competition pitted the Socialists, supported by the Left-Radicals (PRG), Communists and Greens, against the Gaullists, supported by the Union for French Democracy. This configuration was facilitated by a majoritarian electoral system,Footnote14 and by the coattail effects of direct presidential elections. The institutional pressures and historical traditions made any change in this logic highly unlikely, yet, the winner of the 2017 presidential elections was the candidate of a new party, La République En Marche, a party that belongs to neither of the two camps. Accordingly, it proved to cooperate with actors on both sides, in stark contrast with the inherited left-right divisions.

As opposed to the French Fifth Republic, the Italian party system did have a multipolar, centre-based tradition. After 1994, however, the confrontation of the leftist Olive Tree alliance and of the right-wing House of Freedom bloc seemed to have formed a bipolar system. The leaders of the alliances (the Democratic Party and the People of Freedom) were themselves products of mergers, underlying the concentration of the party system. In 1996 and 2008 this two-bloc confrontation manifested itself through the Prodi-Berlusconi rivalry for the premiership. But clear-cut bipolarity proved to be short-lived. The rise of anti-political-establishment and Eurosceptic parties (the reprofiled League, the Five Star Movement/M5S and the Brothers of Italy) led to novel coalitions and partial government alternations (M5S first with the League, then with PD, and finally with both of them in a grand coalition).

Back in the 2000s Austria and Germany appeared as paradigmatic cases of bipolarisation. In the former, the traditional ‘two-and-a-half’ (Blondel, Citation1968) configuration was altered by the rise of the Green movement and by the internal victory of the pragmatic faction over the more fundamentalist (anti-establishment) wing, leading to the formation of a Socialist-Green bloc against a Conservative-liberal camp. The 1998–2005 Socialist-Green government proved that the left no longer needs the liberals to have government access and that the Greens can be reliable partners. In Austria the ‘grand coalition’ formula that dominated party interactions for much of the Cold War period seemed to have ended for good when a purely right-wing coalition was formed between the People's Party (ÖVP) and the Freedom Party (FPÖ), opposed by the leftist Social-democrats and Greens. With hindsight we know that, due to the international outrage at the inclusion of the populists and because of the internal fights among FPÖ factions, no harmonised right-wing bloc developed, but for the contemporaries, this was an open question.

In fact, neither country remained bipolar. First they returned to the ‘grand coalition’ governmental formula. Then, in a further step away from a clear left-right opposition, in Austria the Christian-democrats allied with the Green Alternative, while in Germany, the Social-democrats entered into a coalition with the Greens and the Free Democrats, meaning innovation in government formulae and partial alternation but in the Austrian case the inclusion of a new party into the government.

Icelandic bipolarism was swept away by the 2008 Great Recession. The decline of the traditional parties and the emergence of new ones (e.g. Bright Future, Pirate Party, Liberal Reform Party, Centre Party, People's Party), radically reshaped the party landscape, populating it with actors ready to establish various coalitions.Footnote15

In Poland, the 2005 presidential elections played an instrumental role in terminating the two-bloc (post-communist vs. post-Solidarity parties) structure of competition that developed after the transition to democracy in 1989. A new pattern of competition developed with the liberal Civic Platform (PO) on the left and the conservative Law and Justice (PiS) on the right, the almost pariah status of the once-powerful Left Democratic Alliance and the king-making role of the Polish Peasants’ Party (PSL).Footnote16

In Croatia, North Macedonia and Slovakia, countries that appeared to be bipolar due to the overarching conflict around Communist legacy, the minor parties that existed already in the 2000s between the poles of the party system have proved to be structurally important, often playing the role of king-makers. When Mair published his overview, one may have reasonably expected them to wither away, but from today's vantage point, it is clear that government-building in these countries is greatly influenced by these centrist or ethnic minority actors, often leading to partial alternation in government. The shift was evident in Slovakia, where initially the main line of conflict divided Vladimir Mečiar's nationalist bloc (mainly the Movement for a Democratic Slovakia and the Slovak Nationalist Party), from the anti-Mečiar bloc, which included Liberals, Christian-democrats, Socialist and Hungarian minority representatives, but soon Robert Fico's party, Smer, established its own pole and the emergence of various populist and liberal initiatives have contributed further to the complexity of the party landscape.

In Moldova attitudes towards the EU and Russia originally pitted the Communist Party of Moldova, winning all elections between 1998 and 2014, against those parties in favour of closer relations—even integration—with the EU.Footnote17 But afterwards, the principal right-wing political party (the Liberal Democratic Party) was replaced by two, protest-driven political forces, the Dignity and Truth Party, and the Action and Solidarity Party. The Communists were supplanted by the Socialists, and the character of the Democratic Party was reshaped by the country's main oligarch. Altogether these developments led to a tripolar competition pattern where any of those parties could govern.Footnote18

In neighbouring Romania, bipolarism was weakened when the two major parties (the Socialists and the Democratic Liberals) formed a coalition at the end of 2008. Further realignments took place when the National Liberal Party began to cooperate in government with the Social Democratic Party in 2012, and finally when it merged with the Liberal Democratic Party in 2014. The Social Democrats and the Liberals alternate between fierce rivalry and grand coalition, while the Hungarian minority party tries to play the role of the king-maker, destroying any possibility for the re-emergence of a bipolar structure.

Finally, Andorra's two-party system shifted to a three-party configuration when one of the founders of the PLA created a new political party (Democrats for Andorra/DA) in 2011 and won the early parliamentary elections that very same year. The new complexity is well illustrated by the fact at the 2019 parliamentary elections PLA ran in an electoral coalition with the Socialists, but formed a government with DA.

summarises the classification of European party systems according to trajectories and region, comparing party system types between today (i.e. end of 2020) and the mid-2000s (for country details, please see in the Appendix), when Mair wrote his main pieces on bipolarity. As we can observe, out of the 38 democratic European party systems analysed in this article, up to 22 (almost 60 percent) remained unchanged (10 bipolar, 12 non-bipolar). Out of 16 remaining cases, more than four-fifths (13) abandoned bipolarity, while only three became bipolar. As a result, the ratio of bipolar systems decreased from two-thirds to one-third: the qualitative assessment point in the same direction as the quantitative analysis.

Table 1. A comparison of currently democratic European party systems: mid-2000s vs. 2020.

A contrast with the quantitative approach can also help us validate our categorisations. As indicates using the ‘alternation index’ explained above (see the previous section), the stable multipolar cases have the lowest alternation scores, meaning that they are mostly characterised by the dominance of partial alternation. The stable bipolar cases, on the other hand, are very close to perfect no/wholesale alternation. The cases that underwent party system change are, as expected, in between, with the group that started as multipolar having a more open form of alternation than those that started from the opposite corner. Those systems that moved towards bipolarity, surprisingly, decreased their alternation score. But a closer look at the respective category shows that this is because of one single case, Bulgaria. And Bulgaria was already in 2006 on the verge of bipolarity because the centrist NSDV virtually collapsed at the 2005 elections and had to accept minority status in a left-wing government. Furthermore, the current configuration is not far from multipolarity, with many forces, including the recently emerged There Is Such a People and We Continue the Change challenging the left-right divide. Overall, the alternation scores dovetail with the qualitative assessments.

Table 2. Alternation scores according to types of party systems and periods.

As reveals, the multipolar systems (whether one considers the 2010s or the 2020s separately, or the averages of the two periods) are, as expected, more volatile, more fragmented, have larger anti-establishment parties, have more proportional electoral systems and have more new parties.Footnote19

Table 3. Types of party systems along 6 dimensions.

These results strengthen further the validity of our categorisation, even though the difference is statistically significant only in the case of fragmentation. Given the small N, and considering that we are dealing with virtually the entire universe of European democracies and not a sample of them, the lack of statistical significance does not necessarily mean an actual lack of difference. Even so, we expected a larger gap on some of the key variables. The relative similarity on the dimension of volatility and new parties can be explained with a reference to Mair's point (Citation2006, pp. 70–71), according to which bipolar and multipolar systems can renew electorally. The difference is not in the degree of volatility but rather in the fact that new parties assimilate into existing alliances in bipolar systems, while in multipolar systems, they often form new poles.

The lack of difference on left-right polarisation and on anti-establishment support is more perplexing, as one would expect bipolar systems to score lower on these dimensions. The most likely explanation is that none of these variables captures well what is crucial for the pattern of competition: whether the system contains large enough pariah parties to disturb the periodic alternation of centre-left and centre-right parties or alliances of parties.

The failure of bipolarisation: discussion of likely explanatory factors

In the next and final part of the article, we speculate, based on the political dynamics of the analysed countries, about the factors that played a role in maintaining bipolarity or in undermining the bipolar pattern of competition. When it comes to systems that remained bipolar, we find that the weight of the traditionally strong left-right divide goes a long way to explain the stability of bipolarisation in Denmark, Hungary, Malta, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. In Albania the north–south cleavage seems to have played the functionally equivalent role, while polarisation around religious issues supported the separation of the two camps in Malta, Hungary and Spain. Institutional factors, primarily a disproportional electoral system, also have an evident relevance, but interestingly only in a minority of cases: Greece, Hungary and the United Kingdom. Arguably, the institution of minority governments in Sweden and Norway was also instrumental in making possible the creation of purely left-wing or purely right-wing governments even when no side had an absolute majority in the parliament.

Considering the opposite end of the spectrum, the persistently multipolar countries also share many potentially relevant similarities. They tend to be small, with weak leftist parties, a strong liberal centre, and a proportional electoral system. It seems that under such conditions, bipolarisation strategies have limited scope. Furthermore, in some instances (i.e. Benelux countries and Switzerland) the consociationalist legacy, while in others (e.g. Estonia, Slovenia) the pragmatic, problem-solving culture could have contributed to the survival of complex, multipolar systems. Linguistic or ethnic divides in countries, such as North Macedonia, Moldova, Slovakia, Romania, Belgium or Switzerland, further undermined the development of large homogeneous blocs.

When it comes to categorising party systems in terms of bi- and multipolarity, it would be wrong to assume structural determination. In a certain period, the two-camp logic was under threat even in the most clear-cut bipolar countries. In Greece, for a while, PASOK and New Democracy converged and pariah parties, such as Golden Dawn and the Communists, strived for the status of a new pole. In Spain, the Socialists and Ciudadanos attempted an alliance; in Sweden the radical-left and the Greens were kept at the margins of the system and in the United Kingdom, the Conservative-LibDem government coalition represented a departure from the traditional pattern. But particular developments and elite actions (re)strengthened bipolarity. In Greece, the incorporation of the radical-left (Syriza) and radical-right (LAOS) into a parliamentary majority, in Spain the inclusion of Ciudadanos and Vox into the right and Podemos into the left, in Denmark the inclusion of the Danish People's Party into the government-supporting majority, or in Sweden the weakening of cordon sanitaire against the Swedish Democrats all helped the stabilisation of the bipolar system. The role of specific events, electoral results, splits and mergers, etc. is even more obvious in the 13 cases that show a divergence from the bipolar model. summarises these developments.

Table 4. Systems that moved towards less bipolarity.

These recent shifts to non-bipolarity happened largely because the centre-right preferred the centre-left to the radicals as coalition-partner (e.g. Germany, Ireland), because of the emergence of new forces that aimed at transcending the traditional divides (e.g. France), and because economic crises or corruption scandals forced reshuffles among parties (e.g. Austria, Romania). Populist parties tend to undermine bipolarity either because they are not coalitionable (e.g. Germany, Poland), reducing the possibilities of building governments that do not reach across the aisle, or because they are centrist and, therefore, blur the left-right divide (e.g. Italy, Slovakia). In most cases, the tendency towards multipolarity increased the complexity of government formation (particularly in Germany), reduced cabinet stability (for example, in Italy), had a negative impact on partisan accountability (e.g. in Romania) and decreased party system institutionalisation (most obviously in France). But the elites were largely capable of handling the more complex environment, and the more frequent recombination of political actors rarely appears as a source of public discontent.

Mair was right in thinking that many old-fashioned anti-system parties would either moderate or disappear. The game of government- or parliamentary-majority building, was indeed joined by a large group of previously rejected parties, such as Syriza in Greece, Podemos in Spain, Lega in Italy, the Danish People's Party, etc. Many other parties, such as the Brothers of Italy, Vox in Spain, Sweden Democrats or Jobbik in Hungary, to mention a few, also moved closer to the governmental arena and are ready any day to join the established parties. But a significant number of radical parties remained outside the cordon sanitaire, and new anti-political-establishment parties emerged, forcing the remaining actors to build coalitions that combined parties from the different party blocs. Parties like the Alternative for Germany, National Rally in France, the Party for Freedom and the Forum for Democracy in the Netherlands, the People's Party Our Slovakia, the Alliance for the Union of Romanians, are still rejected, although perhaps not for long. The possibility to create government-ready leftist or rightist alliances is narrowed further by the presence of such parties like the Icelandic and German Pirate Parties or the Dutch Immigrants’ party DENK, which are not focused on governing. Altogether, there was no major increase in the share of ‘coalitionable’ parties. The continuous presence of pariah parties leaves insufficient room for the alternation between two non-overlapping alliances.

In this regard, the decline of catch-all parties, a process that was visible already in the 1990s, cuts both ways. If a swinger centrist party declines (e.g. the National Movement for Stability and Progress in Bulgaria), one that coalesced with left and right, then this helps the development of bipolarity. If, however, centre-left or centre-right parties decline (e.g. Andorra, Moldova), then the maintenance of two exclusive camps becomes difficult.

Like the decline of catch-all parties, the weakening of ideological motivations among some centre-left and centre-right parties had ambiguous consequences. It may have shifted the focus of competition towards governing, but it also blurred the boundaries of party blocs and encouraged competition structured around individual parties, placing impediments in front of alliance-centred politics. In the mass-party phase of European politics, individualistic party strategies were based on strong ideological commitments, homogeneous electorates and subcultural organisations. But such strategies seem to be able to survive even if office-seeking motivations prevail.

During the last two decades, Western Europe underwent a steep socio-political fragmentation process, and, most likely, this factor also played a role in the shift towards multipolarity. In principle, bipolarity can work in fragmented environments (e.g. Norway, Sweden), but, in practice, the existence of many parties provides extra possibilities for innovations in a government building and the experimentation with partial alternation.

There is no single characteristic that would distinguish the ten cases of stable bipolarity from the 13 cases that shifted from a bipolar pattern towards a multipolar one. But in the latter group the majority of the cases experienced the decline (e.g. Germany, Ireland, Slovakia) or even collapse (e.g. France, Italy, Moldova) of mainstream parties. In the former cluster, traditional parties managed to keep hold of their central position in the system, not just at the electoral but also at the governmental level. Only Greece and, to a lesser extent, Spain can be considered an exception.

Concluding notes

Our study has unambiguously demonstrated that the tendency towards increasingly bipolarised party politics has failed to materialise. A truly systematic study about the factors responsible for this outcome is still to be conducted, but our overview suggested a list of institutional, ideological and actor-centred explanations. In this concluding section, we would like to highlight the two factors that we consider the most important in constraining or reversing the tendency towards bipolarity.

First, since the publication of the bipolarisation thesis of Peter Mair the European party politics has changed in major ways. The so-called populist wave, together with the growing relevance of cultural conflicts, led to a multidimensional political space. The destabilising impact of the Great Recession in 2008 and of the European refugee crisis in 2015, and the increasingly centrist role of the Greens, have greatly complicated party politics in the Old Continent, allowing – and sometimes forcing – traditional governing parties to recombine in various ways.

On the other hand, Mair may have underestimated the delicate nature of bipolar politics. Our review indicates that such a configuration requires many preconditions. In the absence of drastic institutional measures such as first-past-the-post voting, and without a deep political divide that symmetrically cuts across the society, bipolar configurations are fragile. The shifts towards non-bipolarity can be caused by the rise of non-coalitionable parties, making grand coalition the only viable option, and by the increasing prominence of new ideological dimensions that foster novel combinations among parties. The bifurcation between government and protest-focused parties does not create bipolar systems because the latter are, by definition, not relevant for governing. The typical result of this type of bifurcation is a series of shifting coalitions with partial replacement among the establishment parties.

Complex coalition-building games have the beneficial impact of encouraging civility across party elites. They must know that (some of) their competitors are also potential coalition partners. They must also acknowledge the multiplicity of political interests in society. At the same time, the possibility of the voters to choose and hold governments accountable diminishes with the rise of multipolarity. According to our overview, this is the case in two-thirds of European countries.

Next to extrapolating the trends observed in the early 2000s, Peter Mair was influenced by the theoretical reasoning according to which elections must be about the choice of government if they cannot be about ideological expressions and programmatic mandates. This led him to expect a general trend towards bipolarity, the ideal configuration for a alternation system. Mair was sceptical about contemporary politics, but perhaps he was not sceptical enough. He assumed that elections need to serve a function, be about ‘something’. What if not?

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to two anonymous reviewers, the two co-editors and the rest of the contributors to the special issue for their comments on an earlier version of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zsolt Enyedi

Zsolt Enyedi is Professor at the Political Science Department of Central European University. He (co)authored three and (co)edited eight volumes and published numerous articles and book chapters, mainly on party politics and political attitudes. Zsolt Enyedi was the 2003 recipient of the Rudolf Wildenmann Prize and the 2004 winner of the Bibó Award. He held fellowships at the Woodrow Wilson Center, Kellogg Institute, Notre Dame University, the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Studies, the European University Institute and SAIS, Johns Hopkins University. In 2020–2021 he was Leverhulme Visiting Professor at the University of Oxford.

Fernando Casal Bértoa

Fernando Casal Bértoa is Associate Professor in the School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Nottingham (United Kingdom). He is co-director of REPRESENT: Research Centre for the Study of Parties and Democracy and a member of the OSCE/ODIHR ‘Core Group of Political Party Experts’. His latest monograph, together with Enyedi (CEU), is titled Party System Closure: Party Alliances, Government Alternative and Democracy in Europe (Oxford University Press, 2021).

Notes

1 As Donovan (Citation2011) pointed out, statements that European politics moves into a bipolar direction were made earlier as well, by Pulzer (Citation1987) and Beyme von (Citation1987).

2 As Richard Katz observed in a discussion of the present article, one could conceptualise bipolarity as the uni-dimensionality of the party systems, which is compatible with large swing parties or pariah parties. We propose the current definition of bipolarity because we consider the structure of the dimensions as separate from the purely relations-based concept of party system. This approach also appears to be in line with the way Peter Mair, and most of the here quoted scholars, conceptualised party systems.

3 For a distinction between blocs and poles, please see Casal Bértoa and Enyedi (Citation2021a, pp. 12–16).

4 Note, however, that D’Alimonte and Bartolini (Citation1997) also added caveats to the bipolar label: observing that individual parties retained their identities and that in 1996 Lega reoccupied the centre.

5 In real life, whether the departure from bipolarity is large or small depends on the size and character of the parties that shift between subsequent coalitions. If a small centrist-pragmatic party alternates between governments led by right-wing or left-wing parties then the departure is small. If partial alternation involves the unpredictable recombination of similar-sized but ideologically different parties then the departure is more significant.

6 The change in the proportion of ministries belonging to specific parties is disregarded when there is no change in coalition membership.

7 Using five-year periods for aggregating the scores is in line with the maximum length in European legislatures and allows us to include at least one election per data point for every country considered in the analysis.

8 For comparative data, see Casal Bértoa and Enyedi (Citation2021a, pp. 113 and 120).

9 The theoretical minimum of the alternation score is 0, but in practice it virtually never falls below 70, providing us with an actual range between 70 and 100. Within this range a drop that is more than 5 points can be considered to be substantial.

10 Majoritarian tier for half of the seats in Andorra, seat-bonus to the largest party in Greece and relatively small average district magnitude in Spain, and 3% electoral threshold in the latter two countries. Only Malta has a proportional electoral system.

11 The Portuguese configuration was close to a two-party format between 1983, when the first attempt to bring together the parties of the right (Democratic Alliance) dissolved, and 2002, when the two main parties (PS and PSD) began to shrink,

12 Liechtenstein experimented with a two-party structure of competition after the 1997 legislative elections, but it returned to the formation of a ‘grand coalition’ between the two major parties (Patriotic Union and Progressive Citizens’ Party) already in 2004, that is, before the publication of Mair’s discussed articles.

13 Other party systems such as the Georgian, Montenegrin and Kosovar ones either did not even exist or were at the early stage of independent existence.

14 Only interrupted in 1986.

15 The clearest example of this is that the Left-Green Movement, marginalised for a decade (1999–2009), managed to capture the Premiership at the end of 2017.

16 The PSL and Agreement, a splinter from PO but later coalition partner of PiS, played the role of swinger parties.

17 Those parties would later form in 2009 the Alliance for European Integration.

18 While beyond the scope of this analysis, it is important to note that the after the July 2021 parliamentary elections Moldova seems to gravitate towards a return to the old bipolar pattern, pitting President Maia Sandu’s Party of Action and Solidarity on the pro-EU side against the Electoral Bloc of Communists and Socialists, and the populist Sor Party on the pro-Russian side.

19 Electoral volatility, which measures the change in partisan preferences between elections, is calculated according to Pedersen’s (Citation1979) index, parliamentary fragmentation according to Laakso and Taagepera’s (Citation1979) ‘effective’ number of parliamentary parties (ENPP) index, and electoral disproportionality according to Gallagher (Citation1991) least squares (LSq.) index. Anti-political-establishment parties (APEp) are defined according to Abedi (Citation2004), and new parties are conceptualised following Sikk (Citation2005). All these data can be found in Casal Bértoa and Enyedi (Citation2021b). We retrieved data on left-right polarisation, using Dalton’s (Citation2008) index, from Döring and Manow (Citation2020).

References

- Abedi, A. (2004). Anti-political establishment parties. A Comparative analysis. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bale, T. (2003). Cinderella and her ugly sisters: The mainstream and extreme right in Europe’s bipolarising Party systems. West European Politics, 26(3), 67–90.

- Bartolini, S., Chiaramonte, A., & D’Alimonte, R. (2004). The Italian party system between parties and coalitions. West European Politics, 27(1), 1–19.

- Beyme von, K. (1987). Parliamentary opposition in Europe. In E. Kolinsky (Ed.), Opposition in Western Europe (pp. 31–51). Beckenham: Croom Helm.

- Blondel, J. (1968). Party systems and patterns of government in western democracies. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 1(2), 180–203.

- Casal Bértoa, F. (2021). Database on WHO GOVERNS in Europe and beyond. The Institutionalization of European Party Systems: Explaining Party Competition in 48 Democracies (1848-2019). Nottingham: PSGo. Retrieved from whogoverns.eu

- Casal Bértoa, F., & Enyedi, Z. (2016). Party system closure and openness: Conceptualization, operationalization and validation. Party Politics, 22(3), 265–277.

- Casal Bértoa, F., & Enyedi, Z. (2021a). Party system closure: Party alliances, government alternatives, and democracy in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Casal Bértoa, F., & Enyedi, Z. (2021b). Who governs Europe? A new historical dataset on governments and party systems since 1848. European Political Science. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-021-00342-w

- Casal Bértoa, F., & Mair, P. (2012). Party system institutionalization across time in post-communist Europe. In M.-R. Ferdinand & K. Hans (Eds.), Party government in the new Europe (pp. 117–130). London: Routledge.

- D'alimonte, R., & Bartolini, S. (1997). ‘Electoral transition’ and party system change in Italy. West European Politics, 20(1), 110–134.

- Dalton, R. J. (2008). The quantity and the quality of party systems: Party system polarization, its measurement, and its consequences. Comparative Political Studies, 41(7), 899–920.

- Donovan, M. (2011). The invention of bipolar politics in Italy. The Italianist, 31(1), 62–78.

- Döring, H., & Manow, P. (2020). Parliaments and governments database (ParlGov): Information on parties, elections and cabinets in modern democracies. Retrieved March 10, 2020, from https://www.parlgov.org

- Gallagher, M. (1991). Proportionality, disproportionality and electoral systems. Electoral Studies, 10(1), 33–51.

- Kam, C., Bertelli, A., & Held, A. (2020). The electoral system, the party system and accountability in parliamentary government. American Political Science Review, 114(3), 744–760.

- Laakso, M., & Taagepera, R. (1979). ‘Effective’ number of parties. A measure with application to West Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 12(1), 3–27.

- Little, C. (2021). Change gradually, then all at once: The general election of February 2020 in the Republic of Ireland. West European Politics, 44(3), 714–723.

- Mair, P. (2001). The green challenge and political competition: How typical is the German experience? German Politics, 10(2), 99–116.

- Mair, P. (2006). Party system change. In R. S. Katz & W. Crotty (Eds.), Handbook of party politics (pp. 63–74). London: Sage.

- Mair, P. (2007). Party systems and alternation in government, 1950– 2000: Innovation and institutionalization. In S. Gloppen & L. Rakner (Eds.), Globalisation and democratisation: Challenges for political parties (pp. 135–153). Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Mair, P. (2008). The challenge to party government. West European Politics, 31(1-2), 211–234.

- Mair, P. (2013). Ruling the Void: The hollowing of Western democracy. New York, NY: Verso Books.

- Müller, W., & Fallend, F. (2004). Changing patterns of party competition in Austria: From multipolar to bipolar system. West European Politics, 27(5), 801–835.

- Pedersen, M. N. (1979). The dynamics of European party systems: Changing patterns of electoral volatility. European Journal of Political Research, 7(1), 1–26.

- Pulzer, P. (1987). Is there life after Dahl? In E. Kolinsky (Ed.), Opposition in Western Europe (pp. 10–30). Beckenham: Croom Helm.

- Sartori, G. (1976). Parties and party systems. A framework for analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sikk, A. (2005). How unstable? Volatility and the genuinely new parties in Eastern Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 44(3), 391–412.

Appendices

Table A1. Included party systems, their time-frame, number of elections and governments.

Table B1. Variation in the nature of currently democratic European party systems between the mid-2000s and the end of 2020.