ABSTRACT

FL literature lessons in Dutch secondary education present a potential dilemma for teachers in terms of language use. On the one hand teachers are encouraged to support target language (TL) input and output to promote foreign language (FL) learning. On the other hand, the curricular culture in the Netherlands has historically stipulated that FL literature teaching should take place in the first language (L1). Furthermore, studies on TL/L1 use in FL lessons suggest teachers and students turn to L1 when discussing complex content such as a passages from a literary texts. As such, it is unknown what is currently happening regarding TL/L1 use during FL literature lessons in the Netherlands. Therefore, this descriptive study investigates how much and during which classroom activities TL/L1 were used in English as a foreign language (EFL) literature classrooms. Twenty-four lessons (four for each of six teachers) were video-recorded and TL/L1 use analysed. Results show that although students used mostly L1, teachers predominantly used TL, revealing them to be actively providing a language focus in EFL literature lessons. TL/L1 use by teachers and students differed between classrooms and individual lessons; TL/L1 choice was generally not determined by classroom activities but by teacher consistency and encouragement.

Introduction and context for this study

While there is general agreement on the importance of Target Language (henceforth TL) use in Foreign Language Teaching (henceforth FLT), teaching reality is often quite different (Hall & Cook, Citation2013). In the Netherlands, the context of our study, this is an interesting issue because Dutch FL teachers are influenced by potentially conflicting interests and objectives that could affect their language choice – that is TL or L1 – in their FL teaching practice.

Literature has been part of the FL curriculum in Dutch secondary education since 1863 (for an overview see Bloemert, Jansen, & van de Grift, Citation2016). Until the 1990s, the literature component was traditionally tested in an oral exam and therefore lectures on literary history were often delivered in TL. This was exceptional in that Dutch FL teaching generally took place in L1 both in the distant past (Wilhelm, Citation2005) and more recently (Hulshof, Kwakernaak, & Wilhelm, Citation2015). Because of the increasing emphasis on experiencing texts and on reading pleasure in the 1990s, Dutch exam regulations prohibited the use of TL in FL literature exams as it was believed TL could hinder students when trying to discuss their reading experience (Kwakernaak, Citation2016a). This had the washback effect of making L1 the preferred language of instruction in FL literature teaching: L1 use was further promoted when the government decided in 1998 that language skills and the literature component should be tested separately. This decision had its effect on the FL literature lessons, which were now – and still are – predominantly taught in L1 (Hulshof et al., Citation2015). As a result, the literature component in FL education has become a separate part in the curriculum, often unconnected to and isolated from students’ FL development (Kwakernaak, Citation2016b).

The issue of using TL or L1 in the teaching of FL literature is connected to the worldwide move towards the integration of FL development and FL literature teaching. An important milestone was the proposed reform by the Modern Language Association, which argued for FL curricula in which ‘language, culture, and literature are taught as a continuous whole’ (Modern Language Association, Citation2007, p. 3). Overall, there has been a growing global awareness that integrating literature and language is a sine qua non; (see Paesani, Citation2011; Paran, Citation2008). Current discussions have moved toward finding a balance between what Paran (Citation2008) calls a ‘language learning focus’ and a ‘literary focus’. Nevertheless, this may not reflect classroom realities, where an increasing focus on literature (rather than on language development) may result in teachers allowing an increased use of the L1 in class (Paran, Citation2008).

In sum, teaching FL literature lessons present a potential dilemma for Dutch FL teachers regarding which language they use. On the one hand, they are convinced of the relevance of TL use, seeing it as a sign of quality (Boon & Tammenga-Helmantel, Citationin press; Haijma, Citation2013; Oosterhof, Jansma, & Tammenga-Helmantel, Citation2014). On the other hand, national language policies have constrained teachers from testing literature in TL. Furthermore, teachers in various contexts have indicated that they prefer to teach complex content in L1 (Bateman, Citation2008; Macaro, Citation2000; Tammenga-Helmantel & Mossing Holsteijn, Citation2016), which would then apply to teaching literature. However, at present no empirical studies exist which examine actual TL/L1 use within EFL literature classrooms and it is unknown what language Dutch EFL teachers use in their literature teaching practice. We therefore conducted a descriptive study exploring the extent of TL/L1 use in literature classrooms by six Dutch EFL teachers and their students. Descriptive research ‘is more concerned with what rather than how or why something has happened’ (Nassaji, Citation2015, p. 129), and it is particularly appropriate for situations where no previous research exists, as is the case here.

Review of the literature

Teachers’ and students’ use of TL/L1

When teaching a FL, usage of TL seems both obvious and essential: input, output, and interactions are core pedagogical principles of FL teaching (Ellis, Citation2005). Recent studies on Dutch FL teaching in secondary education relate TL use to increasing language skills of the students (Dönszelmann, Citation2019; Fasoglio & Tuin, Citation2018; West & Verspoor, Citation2016). International literature reviews (Hall & Cook, Citation2012; Tammenga-Helmantel, van Eisden, Heinemann, & Kliemt, Citation2016) confirmed this. Cai and Cook (Citation2015) found a positive effect on student motivation and classroom climate, and stress the advantages of both L1 and TL use, leading to current discussions on how much and in what classroom activities L1 is used.

Studies investigating how much TL and L1 are used by teachers and students report divergent findings: both high L1 and high TL use, and a range of TL/L1 use between different lessons and between different teachers. Both Rolin-Ianziti and Brownlie (Citation2002) and Macaro (Citation2001) investigated TL use and reported a high use of TL by teachers (see for an overview of the characteristics of the studies). Similar results were reported by Duff and Polio (Citation1990). Cai (Citation2011), on the other hand, found that teachers primarily used L1 in their FL lessons. A similar divergence was reported by Copland and Neokleous (Citation2011). They identified one teacher who conducted their FL classroom almost entirely in L1 and another who conducted it almost entirely in TL. Studies also report ranges in L1 and TL between lessons of the same teacher. For instance, Duff and Polio (Citation1990) found that TL use in the same classroom ranged between 10% and 100%. Considerably fewer studies report on student output, but those that do, display similar variation. Macaro (Citation2001), for example, showed that British secondary school students on average use a large amount of L1 during French lessons. These results did however vary in one teachers' classes between 8% in one lesson and 32% in another. Storch and Aldosari (Citation2010), on the other hand observed that Saudi Arabian college students learning EFL not only generally used TL but they also did so consistently, with a low range of L1 use (between 5% and 12%).

Table 1. Overview of the characteristics of the studies.

Turning to the Dutch context, FL teachers in Dutch secondary education use the TL to a lesser extent than their European colleagues (Bonnet, Citation2004; Kordes & Gille, Citation2013), though TL use in EFL classes is higher than in German or French classes (Haijma, Citation2013; West & Verspoor, Citation2016). The difference between TL use in EFL classes compared to other FL classrooms can be due to differences in status and position between English and other FLs. Compared to other foreign languages EFL dominates: EFL is compulsory for all primary and secondary school students, motivation of students for English in secondary education is higher than for French (Elzenga & de Graaff, Citation2015), and English is omnipresent in Dutch society, creating ample opportunities for students to be exposed to it and in effect developing towards becoming a second language rather than a foreign language.

TL/L1 use in different classroom situations

Although as seen above the quantity of TL/L1 can vary both between and within classrooms, reported TL/L1 use depends to a high extent on classroom activities. For example, Hall and Cook (Citation2013) reported that the majority of the teachers (74%) report using L1 when giving instructions and explaining complex content. Similar results were reported by Polio and Duff (Citation1994), who found that teachers use L1 for grammar instruction and when translating difficult words (see also Bateman, Citation2008; Macaro, Citation2000; Tammenga-Helmantel & Mossing Holsteijn, Citation2016). In other words, L1 is preferred and used when teachers convey new and especially complex content. Also, pedagogically challenging situations (such as giving reprimands) hinder teachers from using TL (Haijma, Citation2013; Oosterhof et al., Citation2014). Another argument for using L1 teachers mention is ‘natural’ and smooth communication (Tammenga-Helmantel et al., Citation2016). On the other hand, TL is often used for linguistically predictable situations (Oosterhof et al., Citation2014) such as the opening and closing of a lesson or classroom activities which can be prepared in advance, such as lectures.

Studies of student preferences regarding TL/L1 use suggest similar patterns. Varshney and Rolin-Ianziti (Citation2006) showed that students prefer L1 for vocabulary and grammar explanation. Additionally, Chavez (Citation2003) found that students’ preferences for language use during discussions of content depended on content complexity: students preferred using L1 when content was complex, such as teaching grammar, and preferred TL when content was familiar and was being repeated. Reasons why students prefer L1 use during complex content are reducing cognitive overload (Scott & de la Fuente, Citation2008), and ‘to understand and make sense of the requirements and content of the task; to focus attention on language form, vocabulary use, and overall organization; and to establish the tone and nature of their collaboration’ (Swain & Lapkin, Citation2000, p. 268).

Research questions

As the literature review above has shown, there is a tension between, on the one hand, the importance of the use of TL in FL content focused classes for language learning purposes, and empirical research showing that L1 use is preferred by teachers and students whenever the focus shifts to content, on the other. Moreover, using TL in FL literature classes is not part of the curricular culture in Dutch secondary education. This therefore raises the question of how much TL/L1 is used and in what classroom activities this takes place within FL literature lessons in Dutch secondary education.

To answer this research question, we take two perspectives, one looking at overall classroom use of TL, and the other examining the way in which TL use was manifest in the specific classroom activities. Our two research questions were therefore:

How much are TL and L1 used by teachers and students during FL literature lessons in Dutch secondary education?

In what literature classroom activities are TL and L1 used by teachers and students in FL literature lessons in Dutch secondary education?

Methodology

Participants

Data was collected in secondary school EFL classrooms at upper-secondary level in schools which focus on pre-university studiesFootnote1 (average level CEFR B2; mean student age 17) from six schools in the Netherlands in September and October 2015. The teachers were participants in a larger research project conducted by the second author (see for background details of the teachers; all names are pseudonyms). All teachers have an MA in English Language Education which, in the Dutch context, requires teachers to attain C1/C2 level. The data consists of four video-recorded lessons of each teacher, making a total of 24 EFL literature lessons. For each teacher, the four observed lessons were the first four EFL literature lessons they taught that particular school year. The teachers were informed that the research was about EFL literature education but they did not know the focus was the use of TL/L1. Because Dutch FL teachers have complete freedom in their literature curriculum design, we have included an overview of the content they taught in these four lessons, which highlights evidences the differences in the choices our participants make (see ). The number of students in the six classes ranged between 21 and 31, and the average lesson time ranged from 40 to 50 minutes.

Table 2. Teacher demographics, class size, and lesson length.

Table 3. Overview of the curriculum material used for each classroom.

Procedure and data analysis

During the video analysis, we made notes for each lesson, concentrating on teachers’ and students’ TL/L1 use and teachers’ instructions regarding TL/L1 use. We determined which language was used by teachers and by students during different literature lesson classroom activities: L1 only; TL only; or a combination of TL/L1. An activity was classified as TL/L1 when teachers switched between TL and L1 within a specific classroom activity, or when we observed they conducted a specific classroom activity, for example a lecture, sometimes entirely in TL and other times entirely in L1. Examples from the videos were used to illustrate the results.

We identified eight different types of activity: lecture episodes, class discussions, group work, student presentations, quiz activities, and reading out loud, as well as reading in silence and watching movie clips. Since the last two activities involve TL use but do not involve production by either the teacher or the students we do not report on them further. During lecture episodes we looked both at the language in which teachers delivered the lecture and at the language students asked or answered questions. For class discussions, we looked at which language was used by both teachers and students throughout. During group work we looked at which language the teacher used when walking around and talking to students, which language students spoke amongst each other, and which language they used when they spoke to their teacher. With the student presentations, we looked at which language students used to present, which language was used by the teacher to give feedback, and which language was used by both teacher and students to ask questions to the presenters. During the quizzes, we looked at which language was used by the teacher to present the quiz questions. Since answers to the quizzes were written, we did not include them in our analysis. During reading out loud in the TL, we looked at which language was used by both teacher and student. We did not investigate lesson classroom activities unrelated to literature, such as off-topic conversation and classroom management. In addition, neither teachers nor students related in the observed lessons to topics other than literature (such as grammar). This situation reflects the Dutch curricular culture where FL literature is a separate subject.

In the results section we present the amount of TL/L1 spoken output by teachers and students. Because lesson time differed from school to school, we provide the percentage based on the total speaking time of each teacher and the percentage based on the total speaking time of each teacher's students. In the appendix we provide an overview of the total amount of minutes both teachers and students used TL/L1 per lesson and the average amount of minutes over the four observed lessons. We acknowledge that other measures would have been possible, especially since learners and teachers, for example, speak at a different rate. However, looking at the amount of time spent talking TL/L1 provides an indication of the relative importance that learners and teachers accord to the two languages in the classroom.

All 24 lessons were coded by the first author. The second author then coded the first lesson of each teacher and interrater reliability was calculated. This resulted in the following Cohen's Kappa scores which show strong agreement: Emma (0.860), Susan (0.861), Anna (0.876), Peter (0.929), Sophie (0.946), and Julia (0.949).

Results

Overview of lessons

gives an overview of how the six teachers structured their lessons, focusing on the classroom activities for the different lessons. It shows that some teachers, such as Peter, Julia and Emma, used a rather consistent structure of activities whereas others, for example Sophie, did not have a strict structure but used a wide variety of activities.

Table 4. General structure of the literature activities for each of the four lessons for all six teachers.

Overall TL use in the lessons observed

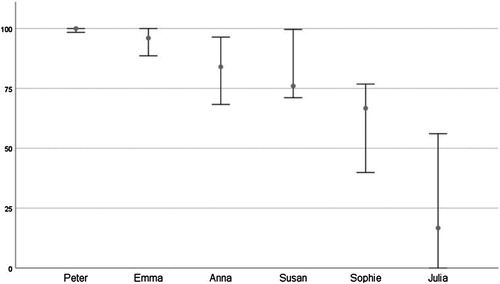

presents the amount and percentage of TL/L1 use by each of the six teachers (see appendix for a detailed overview). In general, we see that most of the teachers, apart from Julia, generally used TL, to a high degree in their EFL literature classrooms. There was, however, a substantial difference between average teacher TL use, which ranges between 16.7% (Julia) and 100% (Peter). Two teachers, Peter and Emma, used very high percentages of TL in all four lessons (100% and 88.6% respectively), with a very narrow range. Three teachers (Sophie, Anna and Susan) used a fairly high percentage of TL in their lessons overall, but differed in their TL use per lesson between 66.7% and 84%; (39.9% to 76.8% for Sophie, 68.3% to 96.4% for Anna, and 71.1% to 99.6% for Susan). Finally, Julia's TL use differed quite markedly from that of the other five teachers. Her average TL use was much lower (16.7%) and the variation, compared to the other teachers, was very high – between 0% and 56.1%. As such, the data shows that teachers seem to fall into three groups: consistently high TL use, generally high TL use with large fluctuations, and generally low TL use with large fluctuations.

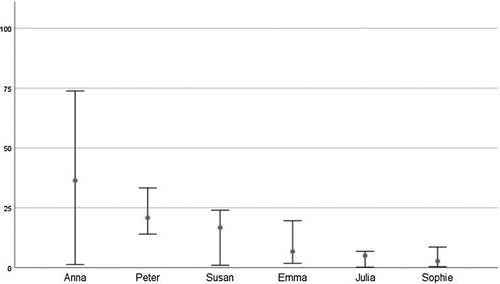

shows that, on average, students used TL in all classrooms during EFL literature lessons, although substantially less than L1. Additionally, there was a considerable variation in average student TL use, ranging between 2.7% for Sophie's students and 36.4% for Anna's students. The results also show that the percentage of TL output by the students differed considerably not only between classrooms but also within classrooms, between the four observed lessons. Julia and Sophie's students showed the lowest averages, and a very limited range. Emma's students showed a low average, but a slightly larger range. Peter and Susan's students showed slightly higher averages (20.8% and 16.7%, respectively) and slightly larger ranges. Here the students who are markedly different from the others are Anna's: her students showed the highest average (36.4%), as well as the largest range (between 1.3% and 73.8%); Anna's lessons two and three were the lessons with the highest percentage of student TL use, and were the only lessons of all 24 in which the students spoke in TL for more than half the time. With lesson time ranging between 40 and 50 minutes, all but Emma's students used TL between one and five minutes on average for the four observed lessons. Emma's students used TL for 16 minutes on average (see appendix). Overall, we found that in all classrooms there was an overall high student L1 use, although substantial differences existed between lessons. Students in our study differed from results found with college students learning English in Saudi Arabia, who generally used mostly TL (Storch & Aldosari, Citation2010), and align more with British secondary school students who were shown to use a large amount of L1 during French lessons but also showed variation between classrooms (Macaro, Citation2001).

TL Use in specific activities

presents an overview of the use of L1, TL or TL/L1 during the different classroom activities observed in each of the six classrooms.

Table 5. General TL/L1 use per classroom activity during the four lessons for teachers and students.

Lectures

All teachers used lectures to teach literature to their students but varied in their language use. Although all six teachers used TL during lectures, Julia and Sophie used L1 as well but exhibited different patterns. Of the four lectures Julia delivered, one took place in TL and the three others in L1. Sophie, on the other hand, used L1 consistently for one lecture and for the other she switched back and forth between TL and L1 throughout.

In all six classrooms students asked or were asked questions during lectures. The language in which students chose to ask and answer varied, but overall students mostly used L1. In Julia's, Anna's, and Emma's classrooms, students asked questions during lectures consistently in L1, even when the teachers delivered the lectures in TL (in Anna's and Emma's case). In Sophie's classroom students used both TL/L1 during the lecture Sophie conducted in TL/L1, and used L1 in the lecture she conducted in L1. Susan's and Peter's students used TL when they asked questions during lectures. Peter was the only teacher to explicitly instruct his students to ask him questions in TL during lectures. When students started in L1 he responded in TL with a light-hearted ‘why are you rasping your throat at me?’, after which students switched to TL.

Group work

A second type of activity all six teachers employed at least once during the four observed lessons was group work. Looking at the language use during group work we found a similar pattern to that which emerged during the lectures: TL/L1 use by teachers varied between only TL (Peter, Emma, and Susan), only L1 (Julia), or a combination (Sophie and Anna). During group work, Anna switched mid-sentence between TL and L1 on several occasions. All students spoke consistently in L1 to each other. The only variation was found with Peter's and Susan's students who switched to TL when they addressed their teacher.

Teachers gave students more instructions on language use during group work than for any other activity (apart from Emma and Anna, who did not explicitly address TL/L1 use during group work). Julia, Sophie, Susan, and Peter all discussed with their students the use of TL/L1 during group work, approaching the topic in varying ways and from different perspectives. Julia, Sophie, and Susan wanted their students to use TL more but were inconsistent in their request and the follow-up; ultimately, they all allowed room for choice. Julia told her students in L1: ‘If the questions are in Dutch the answers are also in Dutch; if the questions are in English the answers are in English’. After a student pointed out the instructions in the reader to answer in L1, Julia responded in L1: ‘If it says so in the reader you can do it in Dutch, but it would be a good exercise’. For the rest of the group work activity, Julia and her students worked on the questions in L1. Sophie also asked in TL that her students discuss the topic in TL – ‘I’d like you to talk about the subject, in English, preferably’ – but she did not enforce TL when her students started talking in L1. Similarly, Susan informed her students in TL that ‘It is good to speak English when you are working together’ but also did not enforce TL use when students talked in L1. Peter, on the other hand, approached the topic from a different perspective. He explicitly informed his students that they could use L1 during group work. He explained in TL that they could ‘do this in Dutch because opinions and knowledge are more important than sanctimonious use of English’.

Class discussions

The pattern of language choice by teachers we found during lectures and group work was also evident during class discussions: use of only TL by Peter, Anna, and Emma, only L1 by Julia, and a combination of TL/L1 by Sophie (note that Susan's lessons did not include class discussions). Students predominantly used both TL/L1 during class discussions, but only L1 in Julia's classroom and only TL in Anna's classroom.

Two teachers, Emma and Peter, explicitly addressed students’ language choice during class discussions. Emma frequently asked students to use TL when answering her questions, though her students did not always do so, sometimes responding in L1. She encouraged TL use but not consistently. For example, when a student responded to one of her questions she said in TL ‘Try English please’, but when a student asked her if she could answer in L1 Emma responded in TL ‘That's fine’. Peter's students mostly used TL during class discussions, unless they visibly struggled with speaking in TL and when, as a result, Peter gave them permission to formulate their answers or ideas in L1. For example, at one point during a class discussion Peter noticed a student having difficulty formulating his answer to the question in TL. He then said in TL, ‘Let's do this in Dutch then! Let's briefly change to Dutch because that's a bit more efficient’. When the discussion on the specific question ended, the discussion continued in TL.

Student presentations

Two of the four observed lessons in Emma's classroom consisted of student presentations which were entirely conducted in TL. Students, in groups of between three and five, prepared a presentation on a specific topic and each lesson contained two to three presentations. Groups of students presented on topics related to racial inequality such as Jim Crow and Rosa Parks. These presentations served to give students historical background on racial inequality, connected to The Member of the Wedding, which they were reading during the project. Emma demanded her students present in TL and she asked questions and gave feedback in TL. When students asked questions to the presenters they also did so in TL.

Quiz activity

Sophie incorporated two quiz activities where she read questions she had prepared on the novel the class was working on and students were asked to write down their answers. The activities focused on The Talented Mr Ripley, and questions students had to answer included, ‘Who does Tom murder and pretend to be?’ and ‘Where in Europe does the novel take place?’ Afterwards Sophie read the correct answers out loud to the class so students could check their answers and see how much of the texts they already knew. Both activities took place entirely in TL.

Reading out loud

In two lessons, one from Emma and one from Julia, we observed students reading out loud from the literary texts, which they did in TL as the texts were in English (this is thus the only activity in which the language being used is not a matter of choice but dictated by the material). In Julia's class every student read a couple of lines of a poem, whereas Emma, on the other hand, asked one student to read out loud several pages from a novel the class was reading. In Julia's case, the poem was To His Coy Mistress by Marvell and the poem was read preceding the explanation of the poem. In Emma's case, the novel read was The Member of the Wedding by McCullers. The students had already been working on the novel for some time and the reading out loud was done at the end of the lesson to fill the last space minutes before the bell rang. One of the students who was good in English volunteered immediately to read and the rest of the class listened and/or read along with the text.

Discussion

In the context of Dutch secondary education, FL literature lessons present a dilemma in terms of TL/L1 use. On the one hand, TL use has been constrained by both the FL curricular culture in the Netherlands (Kwakernaak, Citation2016a) and the use of L1 in many contexts as the preferred language of instruction when content becomes complex (Hall & Cook, Citation2013). On the other hand, TL use is considered a sign of quality according to Dutch FL teachers (Haijma, Citation2013; Oosterhof et al., Citation2014). This study aimed to explore how teachers approach this dilemma and fill the gap in our knowledge of how much and during which classroom activities TL/L1 is presently used by teachers and students in the EFL literature classroom.

Our results show that in all observed EFL literature classrooms TL was used, generally to a high degree by five of the six teachers, revealing most teachers to be actively engaged in providing a language learning focus in the literature classroom. One of the key findings of our study, therefore, is that former national language policies regarding L1 use in FL literature testing have not led to predominant L1 use in EFL literature teaching for the majority of these teachers. Also, we found that teachers do not turn to L1 when discussing complex content. This contradicts previous findings that teachers use L1 when teaching complex content (Hall & Cook, Citation2013). Likewise, our findings are in contrast to previous research, which found that TL was used by teachers only in linguistically predictable classroom activities such as lectures and that L1 was used in less predictable activities such as class discussions or group work (Hall & Cook, Citation2013; Oosterhof et al., Citation2014). We found that in all classrooms there was an overall high L1 use by students, but a substantial difference between lessons, which is consistent with the literature (Macaro, Citation2001; Storch & Aldosari, Citation2010).

Additionally, we found teachers’ TL/L1 use was not determined by specific classroom activities but seemed rather consistent for each teacher throughout their lessons. As such, teacher TL/L1 use was not influenced by classroom activities but seemed to be a matter of consistency. Most teachers gave instructions to their students on TL/L1 use, but they differed in the explicitness and consistency of the encouragement. Only Peter instructed his students regarding their language choice in all his lesson activities: he required TL use from students during lectures and class discussions. Only if his students visibly struggled and were given permission did they use L1. On the other hand, he explicitly instructed his students to use L1 during group work to ensure students could discuss their ideas freely. Julia, Sophie, and Susan all made noncommittal comments to encourage students to use the TL during various classroom activities, but did not enforce TL when students used L1. Nevertheless, although Peter's students did speak more TL than for example Julia's or Sophie's students, what determined student TL quantity the most was the use of classroom activities that required students to speak TL for prolonged periods of time, such as student presentations or reading aloud.

Students generally used TL for a very limited amount of time but their TL/L1 use, however, was to some degree linked to classroom activity: students used L1 during group work and TL during presentations. Group work as observed in our literature classes requires students to engage in spontaneous discussions, tackle questions about texts, develop new ideas, and formulate answers so that L1 use is expected. Student presentations, on the other hand, are prepared in advance and both content and language are therefore predictable, making TL use easier. This ties in to the literature, which shows that TL is often used in linguistically predictable situations (such as presentations) and L1 is chosen when there is a need to feel comfortable and have smooth communication (Oosterhof et al., Citation2014).

Conclusion

This study investigated TL/L1 use in EFL literature classrooms of six secondary school teachers in the Netherlands. Although students used mostly L1, most teachers were actively engaged in providing both a language and a literature learning focus as most use predominantly TL during EFL literature lessons. This suggests that the historically predominant L1 situation for teaching EFL literature in the Netherlands is no longer the status quo. Additionally, we have shown that teachers did not turn to L1 when discussing complex content.

Despite the various insights regarding TL/L1 use from the 24 observed lessons, these results do not reveal whether the use of TL/L1 by teachers was principled and thoughtful, or as Lau, Juby-Smith, and Desbiens (Citation2017, p. 102) put it, purposeful and strategic. Research activities such as stimulated recall would not only provide insights into the extent of principled TL/L1 use but could also add to the knowledge base of why teachers tend to employ either L1 or TL.

Additionally, we recognise that an in-depth analysis of the classroom activities discussed in this study could provide more detailed insights: classroom activities include interaction patterns which are by nature unique, making a comparison between activities intricate. For example, discourse analysis at the intra- and inter-sentential level could reveal the use of translation and code-switching which arguably facilitate the language learning process (Butzkamm & Caldwell, Citation2009; Cook, Citation2010; Levine, Citation2011; Swain Citation1985). See also Hall and Cook (Citation2012) for an overview of empirical studies in support of using translation and code-switching in instructed language learning. Moreover, given that we found that L1 use was not influenced by classroom activities but more by teacher consistency it would be insightful to investigate in which circumstances and for which purpose each teacher allowed themselves to use L1. Such a detailed analysis of classroom interaction patterns could also increase our understanding of the function of L1 use, such as allowing for metalinguistic learning and awareness of TL use by students.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers who commented on our paper for their insightful comments and suggestions for changes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 The Netherlands has a highly tracked secondary educational system. Generally, students are placed in one of the following three tracks between the ages of 12–14: preparatory secondary vocational education, higher general secondary education, and university preparatory education.

References

- Bateman, B. (2008). Student teachers’ attitudes and beliefs about using the target language in the classroom. Foreign Language Annals, 41(1), 11–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2008.tb03277.x

- Bloemert, J., Jansen, E., & van de Grift, W. (2016). Exploring EFL literature approaches in Dutch secondary education. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 29(2), 169–188. doi: 10.1080/07908318.2015.1136324

- Bonnet, G. (Ed.). (2004). The assessment of pupils’ skills in English in eight European Countries 2002: A European project. Paris: European network of policy makers for the evaluation of education systems.

- Boon, N., & Tammenga-Helmantel, M. (in press). Auf Deutsch bitte! Target language use among in-service teachers of German. To appear in Pedagogische Studiën.

- Butzkamm, W., & Caldwell, J. A. (2009). The bilingual reform: A paradigm shift in foreign language teaching. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag.

- Cai, G. (2011). The tertiary English language curriculum in China and its delivery: A critical study. (Unpublished doctoral thesis). Open University, UK.

- Cai, G., & Cook, G. W. D. (2015). Extensive own-language use: A case study of tertiary English language teaching in China. Classroom Discourse, 6(4), 240–264. doi: 10.1080/19463014.2015.1095104

- Chavez, M. (2003). The diglossic foreign-language classroom: Learners’ views on L1 and L2 functions. In C. Blyth (Ed.), The sociolinguistics of foreign-language classrooms: Contributions of the native, near-native, and the non-native speaker (pp. 163–208). Boston: Heinle.

- Cook, G. (2010). Translation in language teaching: An argument for assessment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Copland, F., & Neokleous, G. (2011). L1 to teach L2: Complexities and contradictions. ELT Journal, 65(3), 270–280. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccq047

- Dönszelmann, S. (2019). Doeltaal-leertaal. Didactiek, professionalisering en leereffecten [Target Language – A vehicle for language learning: Pedagogy, professional development and effects on learning]. (Doctoral thesis). Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

- Duff, P., & Polio, C. (1990). How much foreign language is there in the foreign language classroom? The Modern Language Journal, 74(2), 154–166. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1990.tb02561 doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1990.tb02561.x

- Ellis, R. (2005). Principles of instructed language learning. System, 33, 209–224. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2004.12.006

- Elzenga, A., & de Graaff, R. (2015). Motivatie voor Engels en Frans in het tweetalig onderwijs. Zijn leerlingen in het tweetalig onderwijs gemotiveerde taalleerders? [Motivation for English and French in bilingual education. Are students in bilingual education motivated learners of language?]. Levende Talen Tijdschrift, 16(4), 16–26.

- Fasoglio, D., & Tuin, D. (2018). Hoe goed spreken leerlingen Engels als zij het voortgezet onderwijs verlaten? De ERK-streefniveaus onderzocht [How well do students speak English when they leave secondary education? Researching the CEFR standards]. Levende Talen Tijdschrift, 19(1), 3–13.

- Haijma, A. (2013). Duiken in een taalbad: Onderzoek naar het gebruik van doeltaal als voertaal [Diving in a language pool: Research on the use of the target language as the language of instruction]. Levende Talen Tijdschrift, 14(3), 27–40.

- Hall, G., & Cook, G. (2012). Own-language use in language teaching and learning: State of the art. Language Teaching, 45(3), 271–308. doi: 10.1017/S0261444812000067

- Hall, G., & Cook, G. (2013). Own-language use in ELT: Exploring global practices and attitudes. London: British Council.

- Hulshof, H., Kwakernaak, E., & Wilhelm, F. (2015). Geschiedenis van het talenonderwijs in Nederland: Onderwijs in de moderne vreemde talen van 1500 tot heden [History of language education in the Netherlands: Education in modern foreign languages from 1500 up till the present]. Groningen: Passage.

- Kordes, E., & Gille, J. (2013). Vaardigheid Engels en Duits van Nederlandse leerlingen in Europees perspectief [Dutch students’ skills in English and German in a European perspective]. Levende Talen Magazine, 1, 23–27.

- Kwakernaak, E. (2016a). Tussen blokkendoos en taalbad: Waarheen met ons vreemdetalenonderwijs? Deel I [Between a box of blocks and a language bath: Where to with our foreign language education? Part I]. Levende Talen Magazine, 4, 10–15.

- Kwakernaak, E. (2016b). Kennis over talen en culturen [Knowledge of languages and cultures]. Levende Talen Magazine, 7, 28–33.

- Lau, S. M. C., Juby-Smith, B., & Desbiens, I. (2017). Translanguaging for transgressive praxis: Promoting critical literacy in a multiage bilingual classroom. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 14(1), 99–127. doi: 10.1080/15427587.2016.1242371

- Levine, G. (2011). Code choice in the language classroom. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Macaro, E. (2000). Issues in target language teaching. In K. Field (Ed.), Issues in modern foreign language teaching (pp. 171–189). New York: Psychology Press.

- Macaro, E. (2001). Analysing student teachers’ codeswitching in foreign language classrooms: Theories and decision making. The Modern Language Journal, 85(4), 531–548. doi: 10.1111/0026-7902.00124

- Modern Language Association. (2007). Foreign languages and higher education: New structures for a changed world. Profession, 12, 234–245. doi: 10.1632/prof.2007.2007.1.234

- Nassaji, H. (2015). Qualitative and descriptive research: Data type versus data analysis. Language Teaching Research, 19(2), 129–132. doi: 10.1177/1362168815572747

- Oosterhof, J., Jansma, J., & Tammenga-Helmantel, M. (2014). Et si on parlait français? Praktijkgericht onderzoek naar het doeltaal-voertaalgebruik van docenten Frans in de onderbouw [And if we speak French? Practice-based research on lower-level French teachers’ use of the target language as language of instruction]. Levende Talen Tijdschrift, 15(3), 15–27.

- Paesani, K. (2011). Research in language-literature instruction: Meeting the call for change? Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 31, 161–181. doi: 10.1017/S0267190511000043

- Paran, A. (2008). The role of literature in instructed foreign language learning and teaching: An evidence-based survey. Language Teaching, 41(4), 465–496. doi: 10.1017/S026144480800520X

- Polio, C. G., & Duff, P. A. (1994). Teachers’ language use in university foreign language classrooms: A qualitative analysis of English and target language alternation. The Modern Language Journal, 78, 313–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02045.x

- Rolin-Ianziti, J., & Brownlie, S. (2002). Teacher use of learners’ native language in the foreign language classroom. Canadian Modern Language Review, 58(3), 402–426. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.58.3.402

- Scott, V., & de la Fuente, M. J. (2008). What’s the problem? L2 learners’ use of the L1 during consciousness-raising, form-focused tasks. The Modern Language Journal, 92(1), 100–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2008.00689.x

- Storch, N., & Aldosari, A. (2010). Learners’ use of first language (Arabic) in pair work in an EFL class. Language Teaching Research, 14(4), 355–375. doi: 10.1177/1362168810375362

- Swain, M. (1985). Communicative competence: Some role of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. In S. Gass & C. Madden (Eds.), Input in second language acquisition (pp. 235–274). Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

- Swain, M., & Lapkin, S. (2000). Task-based second language learning: The uses of the first language. Language Teaching Research, 4(3), 251–274. doi: 10.1177/136216880000400304

- Tammenga-Helmantel, M., & Mossing Holsteijn, L. (2016). Doeltaal in het moderne vreemdetalenonderwijs. Gebruik en opvattingen van leraren in opleiding [Target language in modern foreign language teaching. Teacher trainees’ use and views]. Groningen: Rapportage Meesterschapsteam Vakdidactiek MVT.

- Tammenga-Helmantel, M., van Eisden, W., Heinemann, A., & Kliemt, C. (2016). Über den Effekt des Zielsprachengebrauchs im Fremdsprachenunterricht: Eine Bestandsaufnahme [About the effect of target language use in foreign language teaching: An inventory]. Deutsch als Fremdsprache, 53, 30–38.

- Varshney, R., & Rolin-Ianziti, J. (2006). Student perceptions of L1 use in the foreign language classroom: Help or hindrance? Journal of the Australasian Universities Language and Literature Association, 105, 55–83. doi: 10.1179/000127906805260338

- West, L., & Verspoor, M. (2016). An impression of foreign language teaching approaches in the Netherlands. Levende Talen Tijdschrift, 17(4), 26–36.

- Wilhelm, F. (2005). English in the Netherlands: A history of foreign language teaching 1800–1920. Utrecht: Gopher Publishers.