ABSTRACT

Today, in an era of increased mobility and migration, there is also increased in-migration within regions and countries. In the case of Norway, there is high tolerance for dialect use, and in this context, it is interesting to ask which kinds of sociolinguistic strategies in-migrants consider to be available given their current situation. This article explores the reported language attitudes from the point of view of people who have moved to Tromsø from other parts of Norway. The data is from a survey about (1) in-migrants’ attitudes towards various forms of dialect use, including dialect maintenance, shifts or changes, and (2) how the in-migrants perceive attitudes in Tromsø towards various forms of dialect use. The study shows that it is seen as ideal to maintain one’s initial dialect, rather than changing or shifting the dialect. However, most of the respondents reportedly changed their own initial dialect and changing or shifting the dialect is perceived as a tolerable sociolinguistic strategy to fit in and accommodate the new place. We also find that a common assumption is that people in Tromsø have positive attitudes towards other dialects, but it seems to matter where one comes from and which dialect one speaks.

1. Introduction

Norway is sometimes described as an exceptionally liberal speech community with high tolerance for dialect use in most contexts (see, e.g. Jahr and Janicki Citation1995; Wiggen Citation1995; Røyneland Citation2009). For instance, Trudgill (Citation2002, 31) says that “Norway is […] one of the most dialect-speaking countries in Europe”, and that Norway has “an enormous social tolerance for linguistic diversity.” In Norway, dialects are not only used in private contexts, as in many other European countries, but also are generally accepted in public domains. However, during the last decade or so, several studies have contributed to modifying this rather one-sided portrayal of Norway, showing for instance that some dialects have more prestige than others (see, e.g. Mæhlum and Røyneland Citation2009, Citation2018; Mæhlum Citation2011; Sollid Citation2014).

Our aim is to look closer at this exceptionally liberal speech community from the perspective of in-migrants to Tromsø who speak Norwegian as a first language. Looking at Tromsø in this context is interesting for several reasons. First, in Norway attitudes toward Northern Norwegian dialects, including the Tromsø dialect, have generally been quite negative (cf. Sollid Citation2014). For example, house-to-rent advertising from about 1950–1960 specified that people from the north were not wanted. However, this situation has changed, and the dialect wave in the 1970s contributed to less linguistic stigmatization. Second, there has been an enormous growth in the population of the Tromsø municipality during the last few decades, from 33,310 inhabitants in 1965 to 76,974 as of 1 January 2020. Tromsø is the largest urban area in a vast and rather sparsely populated region and the processes of centralization and urbanization are prominent. The city is linguistically and culturally diverse, as it is a meeting place for people with a wide range of linguistic and geographic backgrounds and experiences. The exceptional population growth in the area is primarily due to in-migration from other parts of the country, which is our main interest in this article. In addition, there is considerable immigration from other countries (cf. Sollid Citation2019). Consequently, Tromsø is linguistically and culturally diverse. Concurrent with these changes in the linguistic climate and in the Tromsø population, the Tromsø dialect is going through processes of linguistic levelling (cf. Nesse and Sollid Citation2010; Sollid Citation2014). Thus, there are on-going sociolinguistic changes in Tromsø. The concept sociolinguistic change refers to situations where the intersection of language use and society is constantly developing, for instance with respect to the sociolinguistic strategies that are perceived as possible for dialect speakers (Coupland Citation2014; Ommeren Citation2016), i.e. whether they maintain, change or shift their dialects. However, the sociolinguistic climate, i.e. the language attitudes and ideologies that frame and shape language use, has been only somewhat explored to date (cf. Bull Citation1996; Nesse and Sollid Citation2010; Sollid Citation2014), and so far there is only one study of the experiences of Norwegian dialect speakers moving to Tromsø (cf. Jorung Citation2018 study of four speakers from Oslo in Tromsø). With our study, we aim to fill this knowledge gap.

This study investigates the reported experiences of speakers of Norwegian dialects who have moved to Tromsø from different parts of Norway. Based on both quantitative and qualitative data from a questionnaire study, we are (1) interested in their attitudes towards various forms of dialect use, including dialect maintenance, shifts or changes, and we are (2) interested in how the in-migrants perceive attitudes in Tromsø towards various forms of dialect use. The quantitative data are from closed questionnaire questions, while the qualitative data are metalinguistic comments to the closed questions in the survey.

Part 2 provides an outline of the theoretical backdrop for this article. Part 3 presents methodological approaches and considerations, while the main findings of the survey are presented in part 4. Finally, the main findings are discussed in part 5.

2. Theoretical backdrop

The theoretical concept that makes up the main backdrop for our study is language attitudes, and we also include perspectives from research on language ideologies. Seen together, language attitudes and language ideologies contribute to describing a sociolinguistic climate that surrounds dialect speakers.

There are several definitions of the term attitude in language attitudes literature, and there are ongoing discussions on how it should be defined (e.g. Garrett Citation2010; Albarracin, Johnson, and Zanna Citation2014). In earlier research, there was a tendency to consider an attitude as a stable and durable quality of the individual, while current research is more open for understanding the attitude as brief. According to Allport (Citation1954), the attitude is: “a learned disposition to think, feel and behave toward a person (or object) in a particular way”. As seen in this definition, attitudes are thoughts, emotions and behaviour. Moreover, Allport describes the attitude as learned. Sarnoff (Citation1970, 279) explains attitudes as “a disposition to react favourably or unfavourably to a class of objects”. This definition considers how we relate to a social object of some sort, for example language. Both Allport (Citation1954) and Sarnoff (Citation1970) explain the attitude as a disposition, and thus imply a certain degree of stability in the attitude, which allows it to be identified. In more recent research, however, it is common to differentiate between various degrees of commitment: strong commitment when the attitudes are deeply rooted and durable, and weak commitment when the attitudes are shallow and unstable (Garrett, Williams, and Coupland Citation2003). Furthermore, Oppenheim (Citation1982, 39) defines the attitude as

a construction, an abstraction which cannot be directly apprehended. It is an inner component of mental life which expresses itself, directly or indirectly, through much more obvious processes as stereotypes, beliefs, verbal statements or reactions, ideas and opinions, selective recall, anger or satisfaction or some other emotion and in various other aspects of behaviour.

According to this definition, attitudes are psychological constructs. However, psychological constructs cannot be observed directly, and within attitudes research there are often discussions on how to study them. We need to infer from what we see or hear (i.e. various forms of behaviour), and we return to the question of how we research language attitudes below. Here we summarize by saying that we see language attitudes as psychological constructs that are learned dispositions to react favourably or unfavourably towards language and language use. In our study we are interested in the reported attitudes towards the own language use after moving to Tromsø, and also the perceived attitudes in Tromsø towards various forms of dialect use.

While language attitudes here is understood as psychological constructs, we argue with Rosa and Burdick (Citation2016, 108) that language ideologies are mediating forces through which language and language use is made meaningful for the individual in culturally specific ways. In the following we therefor elaborate on the sociolinguistic climate in the surroundings of our respondents through describing relevant language ideologies, i.e. “the cultural system of ideas about social and linguistic relationships, together with their loading of moral and political interests” (Irvine Citation1989, 225).

Based on previous research (e.g. Omdal Citation1994; Haugen Citation2004; Mæhlum and Røyneland Citation2009, Citation2018; Røyneland Citation2009; Sollid Citation2009, Citation2014; Mæhlum Citation2011; Ommeren Citation2016), there are mainly two Norwegian language ideologies that are relevant for our purposes. First, there is a high acceptance of dialects in Norway, but as indicated in the introduction, this is not acceptance without frames or limits. There is a prevailing idea of a “proper” or “authentic” Norwegian dialect. This language ideology is related to the period after the Danish–Norwegian union and is part of the nation-building process that occurred during the nineteenth century. Part of the linguistic differentiation of Norwegian from Danish was also embracing dialects that showed a link beyond the 400 years of union (Sollid Citation2009). This also includes consolidation of what is considered Norwegian and, in consequence, a process of homogenization. In this context, Northern Norwegian dialects were not included in the idea of what were considered to be proper Norwegian dialects (Sollid Citation2014). The main reason why Northern Norway became irrelevant was extensive language contact and multilingualism involving the Sámi, Kven and Norwegian languages. The language policy of the second half of the century aimed at promoting Norwegian at the expense of Sámi and Kven. Ultimately, features of linguistic contact were indicative of non-Norwegianness.

Second, there is an expectation that speakers maintain their initial dialects. Thus, dialect shift and bidialectism are not considered valid strategies during migration within Norway (Ommeren Citation2016). The first dialect of a speaker is their “authentic dialect”, and thus there are social costs if the speaker shifts to another dialect (Røyneland Citation2017). At the same time, there might be social costs if the speaker chooses to maintain their dialect, as is the case for speakers of Northern Norwegian dialects that indicate a Sámi or Kven background. In the same vein, if the speaker mixes and uses features from other dialects or languages, the first dialect is devalued for being “broken” or “impure.” In Norwegian, the folk concept of knot denotes an undesirable and inauthentic linguistic practice (Molde Citation2007) in which the speaker uses language to differentiate between their previous and current social or geographical belonging. This linguistic practice is seen as a less prestigious way of speaking. However, what is considered prestigious changes between contexts.

These two language ideologies originate from the same dominating idea, namely purism. As a language ideology, purism is relevant both in a Norwegian and in a Northern Norwegian context (cf. Røyneland Citation2017). Thomas (Citation1991, 12) links linguistic purism to a desire to preserve language:

Purism is the manifestation of a desire on the part of a speech community (or some section of it) to preserve a language from, or rid it of, putative foreign elements or other elements held to be undesirable (including those originating in dialects, sociolects and styles of the same language). It may be directed at all linguistic levels but primarily the lexicon. Above all, purism is an aspect of the codification, cultivation and planning of standard languages.

As Mæhlum (Citation2011) points out, purism is a dominating feature of the general sociolinguistic climate. Inscribed in this is a view of a language or a dialect as a whole unit. Furthermore, purism is linked to a view of one historical version of a language or a dialect as purer and hence a more desirable version of the language or dialect (cf. also Thomas 1991). Although purism is an old language ideology going back to the era of standardization of written languages in Europe (Brunstad Citation2001, Citation2003), purism can still be seen as part of the Norwegian linguistic climate as a desire to keep the dialects pure and as an essentialist idea of identity. In light of this, identity is a permanent and unchangeable condition, immune to external influence and change. An outcome of the idea of language purism is the devaluation of mixing features from different languages and also shifting dialects. Even though this is a significant part of the sociolinguistic climate, there is some resistance towards purism and normativity (Mæhlum and Røyneland Citation2009, 223).

Considering this general description of the linguistic climate of Norway and Northern Norway, Tromsø can be said to have an intermediate position. The official status as city (kjøpstadsprivilegium) from 1794 attracted government officials and other members of the middle class, who had a middle-class, delocalized way of speaking (cf. Sollid Citation2014). Local dialects in and from the area around Tromsø were the main basis for the emerging Tromsø dialect, and as the city grew, it became important to differentiate between the city dialect and surrounding rural dialects. Thus, on the one hand, Tromsø was a Northern dialect that was affiliated with the cultures and languages of the Sámi and Kven peoples. On the other hand, there was a process of linguistic differentiation (cf. Irvine and Gal Citation2000) between the city and rural communities and dialects between certain ways of speaking and the city of Tromsø. Today, as the Tromsø dialect undergoes constant change, there seems to be weaker differentiation between urban and rural Northern dialects (cf. Nesse and Sollid Citation2010).

In this sociolinguistic context, it is interesting to ask what people who move to Tromsø think of their sociolinguistic options. In an ethnographic study, Jorung (Citation2018) finds that her four participants from Oslo have different linguistic strategies for blending in in Tromsø, ranging from using the variation within the Oslo dialect to using a mix of the Oslo and Tromsø dialects. The participants reflect on their experiences in light of authenticity, using their relationships to both Oslo and Tromsø as points of reference for what is considered authentic.

3. Methodological considerations

3.1. Approaching language attitudes

The data in our study is gathered using a questionnaire. The questionnaire has four parts with questions about: (1) the informant’s background, (2) dialect use and identity, (3) attitudes towards dialect use and change, and (4) personal experiences of the moving situation and of changes in social and linguistic environment (cf. the questionnaire in Omdal Citation1994). The criteria for participation was that they all have experienced moving to the city at some point in their lives and that they all have Norwegian as their first language. The form contains a mixture of open-ended, multiple choice and closed questions, where the closed questions have the three response alternatives “yes”, “no” and “other” and the “other” alternative is open. All in all, the questionnaire contains 57 questions. It was distributed electronically, both via the online version of the local newspaper iTromsø and via e-mail to deans at the University of Tromsø (UiT), who further shared it with employees at their faculties, and to headmasters at various local schools, who furthered it to teachers at their schools. The university and the University Hospital of Northern Norway (UNN) are the two largest workplaces in the city, and many people move to Tromsø in order to study or to work at these institutions. With that in mind, it is relatively fair to assume that we find a high ratio of in-migrants among these employees. The survey was completed in February 2015.

Within language attitudes research, there are generally three wide approaches: (1) content analysis, which focuses on how language varieties are treated and commented on in a society, (2) direct approach, such as questionnaires and interviews, and (3) indirect approach, often referred to as “the speaker evaluation paradigm” or the matched guise technique (Lambert et al. Citation1960). The direct approach, which is the approach used in this study, involves asking direct questions about language attitudes, evaluations, preferences, etc. (Garrett Citation2010). There are some problems that often occur with direct approaches and with the formulation of questions that the respondents are asked (cf. Garrett Citation2010). First, the researcher may ask hypothetical questions about how people would react to a particular object, event or action. As Garrett (Citation2010, 43) points out, “responses to these sorts of questions are often poor predictors of people’s future behaviour in a situation where they actually encounter such objects, events or actions”. Thus, if one investigates attitudes and the relation between attitudes and behaviour, answers to hypothetical questions may not be that insightful. There is also a chance of asking strongly slanted questions, such as questions containing more or less loaded words that tend to push people into answering one way (e.g. “Nazi”, “bosses”, “healthy”). Questions may also be slanted by their overall leading content. Furthermore, another potential pitfall is asking multiple questions, which may give responses that are difficult to interpret since they can refer to more than one component of the question, or that they are ambiguous.

In addition to the wording of questions, there can be certain inclinations or biases in people’s responses, such as social desirability bias and acquiescence bias (cf. Garrett Citation2010). While acquiescence bias implies that some respondents tend to agree with an item, regardless of what it concerns, social desirability bias is the tendency for people to respond to questions in ways that they perceive to be socially appropriate. In studies of attitudes towards languages or dialects, the respondents may reproduce attitudes that they have learned or experienced as desirable in various situations.

In all likelihood, social desirability and acquiescence bias affect some people and attitudes more than others. As Garrett (Citation2010, 45) argues, “it may well be that they have a greater effect where the issues are of some personal sensitivity, or where the issues are less likely to have been well thought through.” Of course, this could be an issue with the questions in our survey. Nevertheless, dialect use and attitudes are typically not very sensitive issues in Norway. In contrast, they seem to be rather popular and common topics, especially when people from different parts of the country meet. Also, as Oppenheim (Citation1992) argues, social desirability bias is of less significance in questionnaires than in interviews. Questionnaires ensure a high degree of individual anonymity, which could make it more comfortable for the respondents to express various opinions, not just those that are socially appropriate.

In our study, we are interested in looking at correlations and overall tendencies in the data as well as what the respondents themselves say about dialect use and attitudes. Metalingual statements constitute a relatively large proportion of the data. Common features in experiences and reported linguistic practices among the respondents in the survey could be related to the influence of similar ideological beliefs about language. However, it is not always clear where such beliefs are located. Coupland and Jaworski (Citation2012, 36), referring to Schieffelin, Woolard, and Kroskrity (Citation1998, 9), suggest that

they inhere in language use itself, in explicit talk about language (that is, in metalanguage), in implicit metapragmatics (indirect signalling within the stream of discourse), or at least partly as “doxa”, “naturalized dominant ideologies that rarely rise to discursive consciousness.”

As they further point out, language is necessarily used with sets of various assumptions, such as thoughts about what is “correct”, “appropriate”, “permissible”, “normal” and so on as well as assumptions about the default meaning of an indexical expression (Silverstein Citation1998), which varies between times and places. Such evaluative and prescriptive assumptions are ideological. Of course, relying on reported language use is potentially problematic. Using such data is often followed by a fair amount of scientifically articulated scepticism regarding how much one should trust these reports and how such data should be used. For example, the use of technical tools within language studies has made it possible to compare what people say that they say with what they actually say, and such comparisons have shown that self-reports about language use and actual language use are not always in accordance with each other. Thus, self-reports are not necessarily a good method for mapping actual language use (cf. Labov Citation1966). However, people’s reports (i.e. folk linguistic beliefs; cf. Preston Citation1993) about language use can be used as data in sociolinguistic studies. There is potential in this kind of empiricism, especially as a basis for understanding the investigated speech community. In our study, looking at reported language use could provide insight into the social meaning of various linguistic practices in Tromsø, i.e. how the respondents describe both their own linguistic practices, and other’s perceptions of their linguistic practice as in-migrants.

3.2. Presentation of the respondents

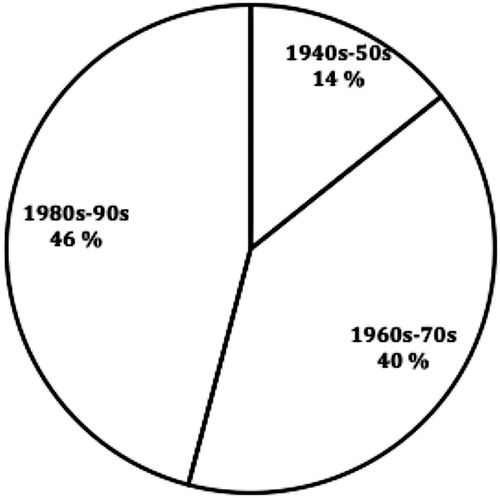

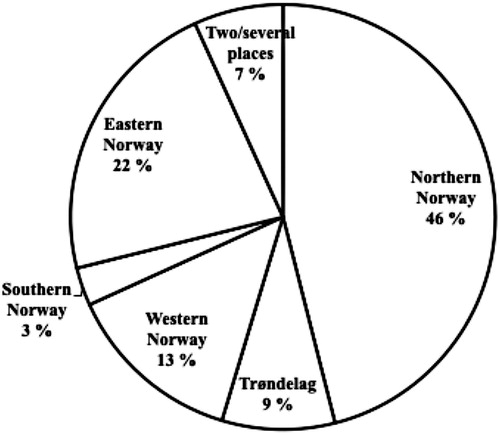

The questionnaire gathered responses from a total of 282 respondents. About two thirds of the participants are female, and the average age is around 40 (i.e. born 1975–76). However, they are very diverse when it comes to age, the oldest one being born in 1944 and the youngest in 1995. As shown in and , the respondents are mostly born between 1960 and 2000. Also, many of the respondents (46%) have moved to Tromsø from different parts of Northern Norway, which in this context refers to the counties Troms and Finnmark and Nordland. The second largest group of participants (22%) come from Eastern Norway, which includes the counties Viken, Oslo, Innlandet, Vestfold og Telemark, while some (13%) come from Western Norway, which includes the counties Møre og Romsdal, Vestland and Rogaland. A few respondents (9%) come from Trøndelag and (3%) come from Southern Norway, which is the county Agder. Some (7%) have more than one place of origin, which in this context means that they have grown up in more than one part of Norway or in more than one country. Furthermore, around half of the respondents have moved to Tromsø during the last ten years, while some (39%) have lived in the city for 11–30 years. A few (10%) have lived in Tromsø for over 30 years.

The survey has an overrepresentation of respondents within higher education. They are mainly employees or students at the university, at the university hospital, and at various elementary and high schools in the city. A relatively small proportion of the respondents (15%) say that they are currently in school or unemployed. This means that the respondents in our survey represent a somewhat uneven picture of the Tromsø population. Thus, this is a nonrandom sample, and “nonrandom samples are likely to have som bias in them” (Johnson Citation2008, 35). The weakness of this method is obvious, and since the respondents in our survey are not a random selection of the Tromsø population, we cannot make statistical generalizations. Purely statistical generalizations can only be made if the selection of a population is perceived to be a random selection of the given population (Aalen Citation1998, 199). At the same time, efforts were made to compensate for this weakness by trying to get a high response rate. The respondents were rewarded for finishing the questionnaire, and the reward was being included in a drawing of lottery tickets.

Collecting linguistic data over the Internet can be seen as a continuation of the questionnaire tradition as we know it from classical dialectology (Chambers and Trudgill Citation1980, 24f.; Eichhoff Citation1982; Knoop, Putschke, and Wiegand Citation1982; cited in Hårstad Citation2010, 138). Although there is a longstanding tradition within linguistics using the questionnaire as a method for collecting linguistic data, this approach is relatively new within dialectology (Hårstad Citation2010, 138). Indeed, the Internet has been used as a source for linguistic data, but perhaps mostly within corpus linguistics and lexicographical studies (Grefenstette Citation2002; cited in Atteslander Citation2005, 1072f.; Hårstad Citation2010, 139). Akselberg (Citation2008) was one of the first to experiment with the Internet as a medium for studying language in Scandinavia. Both Akselberg and Hårstad used online newspapers to publish questionnaires about language in Bergen (Akselberg Citation2008) and in Trondheim (Hårstad Citation2008, Citation2010). A similar questionnaire survey was conducted in Oslo (Stjernholm and Ims Citation2014). Transferring the questionnaire technique to the Internet has one obvious advantage; one can reach out to a large number of language users within a relatively short amount of time and at low costs. However, there is widespread scepticism towards using the Internet to collect linguistic data (cf. Hårstad Citation2008, 138ff.), which mainly concerns challenges attached to validity and representativeness. Among other things, Hårstad mentions Best and Krueger (Citation2004), who argue that people’s access to the Internet can vary. Hårstad (Citation2008, 140–141) also discuss problems with non-responses among respondents, in addition to challenges attached to the test situation, including that it is quite complex and difficult to control. For example, we have limited access to what the respondents mean with their evaluations. We do not know if the respondents answer what they think they say, what they think they should say, or what others think they should say. Similarly, we do not know if they answer what they think they should mean (referred to as “the social desirability bias”, see part 3.1. and part 5).

4. Findings

4.1. Overall tendencies and correlations

When the respondents in our survey describe their own way of speaking, we get a first look into folk linguistic aspects of the data. In the “dialect use”-part of the questionnaire, one open-ended question is “Which dialect(s) do you speak?Footnote1”. Almost all of the respondents have submitted individual responses to this, and the individual responses are further arranged into categories based on how detailed they are. Most of the respondents (60%) report that they speak other dialects than the Tromsø dialect, including dialects from the north, mid, west, south and east part of the country. Some (5.3%) report that they speak “no dialect at all” or “bokmål”, the latter usually referring to dialects that are close to bokmål, which is the most used of the two official written standards in Norway. Some of the respondents (7.4%) only write that they speak Northern Norwegian, and they do not explain it any further.

Another question in this part of the questionnaire is “How will you describe your way of speaking?Footnote2”. This is a multiple-choice question with response alternatives that provide the respondents with prefabricated formulations. Around half of the respondents (54%) choose a response alternative that is suggesting that they speak “mixed” and that they have a dialect with features from several dialects. A few (4%) claim that they can shift between dialects, and that they do not “mix” them. Several (37%) report that they have only one dialect.

There seems to be a difference in what the respondents mean by “speaking mixed”. One respondent writes that they speak a “mixed dialect. I can change between Tromsø and Stavanger dialect, but the Tromsø dialect will be a mixed dialectFootnote3”. Another writes: “I don’t mix, but vary a lot within Trondheim dialect kjem/kommerFootnote4 etc. depending on who I speak withFootnote5”. Other respondents write: “Only one dialect, but with elements/words from other dialectsFootnote6”. In one comment, the Norwegian word avslepen (i.e. “honed” or “ground”) is used as a description. This is an expression often used about levelled dialects. These metalinguistic comments from the data show that although people’s comments about language at times can be quite inaccurate from a linguist’s point of view, such comments can still be highly interesting and helpful to understand how they conceptualize their linguistic surroundings.

The findings from the survey show that many of the respondents are positive towards dialect use, and over 80% report that they like both the Tromsø dialect and the dialect from their homeplace. This is an indication of the tolerance towards dialects and dialect use in Norway (e.g. Trudgill Citation2002), where most speakers have positive attitudes towards their own and also other’s dialects. indicates that over 60% of the respondents think that in-migrants should keep their distinctive features (including food, clothes and languages) when they move to Tromsø. also indicates that this was an engaging question; several of the respondents (31%) provide comments under “other” (cf. section 4.3).

Figure 3. “Do you think in-migrants should keep their distinctive features when they settle down in the city (including food, clothes, languages)? [Synes du innflytterne bør holde på sitt særpreg når de har bosatt seg i byen (også mat, klær, språk)?]” The figure shows percentage distribution (n = 279).

![Figure 3. “Do you think in-migrants should keep their distinctive features when they settle down in the city (including food, clothes, languages)? [Synes du innflytterne bør holde på sitt særpreg når de har bosatt seg i byen (også mat, klær, språk)?]” The figure shows percentage distribution (n = 279).](/cms/asset/90ce6890-6af2-47f5-bdd9-6c9bc4deb71d/sabo_a_1911209_f0003_ob.jpg)

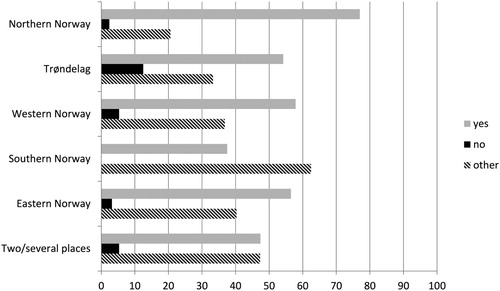

At this point it is interesting to ask whether it matters where the respondent comes from. displays the percentage distribution of responses to this question according to the place of origin. Several of the Northern Norwegian respondents (77%) answer that people should keep their distinctive features when they move to Tromsø. This could indicate that they are liberally inclined towards the newcomers, but it may also indicate that they are more reluctant towards change than respondents from other parts of the country. Also, the Northern Norwegian respondents have the lowest percentage of comments under “other” (20.6%), and very few answered “no” (2.4%). The Southern Norwegians and respondents that have lived two or more places seem to be the least reluctant towards change. They also have the highest percentage of comments in the “other” section (62.5%). In general, the respondents commented quite frequently on this question (cf. section 4.3).

Figure 4. “Do you think in-migrants should keep their distinctive features when they settle down in the city (including food, clothes, languages)?” The figure shows percentage distribution according to place of origin (n = 279).

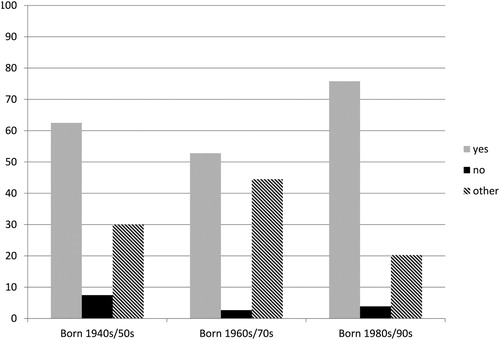

shows the percentage distribution of responses to this question according to birth year. The differences in these responses are not particularly striking, but the youngest respondents seem to be somewhat more liberal towards the newcomers compared to older respondents. In the group of respondents born in the 1960s/70s, almost half of them reflect on this question in the “other” section.

Figure 5. “Do you think in-migrants should keep their distinctive features when they settle down in the city (including food, clothes, languages)?” The figure shows percentage distribution according to birth year (n = 279).

Most of the respondents (80%) do not think that it is necessary for people from their homeplace to change or shift their dialect in order to be understood when moving to Tromsø (cf. ). Of those respondents answering that people from their homeplace need to change their dialect, the highest percentage were from Western Norway, and the lowest percentage were from Trøndelag. Respondents from Trøndelag had the highest percentage of individual comments to this question. None of the respondents that moved two or more times answer that it is necessary to change their dialect to be understood in Tromsø.

Figure 6. “When people from your homeplace move to Tromsø, is it necessary to change the dialect in order to be understood? [Når folk fra ditt hjemsted flytter til Tromsø, er det da nødvendig å endre på dialekten for å bli forstått?]” The figure shows percentage distribution according to place of origin (n = 282).

![Figure 6. “When people from your homeplace move to Tromsø, is it necessary to change the dialect in order to be understood? [Når folk fra ditt hjemsted flytter til Tromsø, er det da nødvendig å endre på dialekten for å bli forstått?]” The figure shows percentage distribution according to place of origin (n = 282).](/cms/asset/8ed30d0d-7296-4676-b60a-82e7ad755d80/sabo_a_1911209_f0006_ob.jpg)

Over half of the respondents (69%) report that they have changed their dialect, while some (21%) answer “no” or that they are unsure (10%). In addition, a substantial amount of the respondents (87%) report that they have received either positive or negative comments on their dialects.

Many of the respondents (53%) answer that they think tromsøværinger (people from Tromsø) generally like the dialect of the respondent’s homeplace. Some (24%) answer “no”, and some (23%) submit individual responses. An especially interesting insight emerges when these responses are distributed according to place of origin (cf. ): there is a clear difference in perception between the respondents from Eastern Norway and respondents from other parts of the country. Several of the respondents from Eastern Norway (45%) do not think that tromsøværinger generally like the dialect of the respondent’s homeplace. The percentage of positive responses is highest among respondents from Western Norway, Trøndelag and Northern Norway.

4.2. Qualitative responses

When asked if in-migrants should keep their distinctive features when they settle down in Tromsø (cf. and ), many of the respondents express that this is a complex question that deserves more than a simple “yes” or “no” answer. Some comment that it depends on what it concerns (i.e. whether it is food, clothes or language), but over half of the comments in the “other” section indicate that people should do what they want and that the respondents do not want to adopt a normative or moralistic stance on other people’s choices. Others emphasize integration and point out that accommodation is important to fit in and be understood. According to several of the comments in the “other” section, the ideal seems to be to keep distinctive features and be accommodating in regard to the new place. Languages and dialects are often mentioned in the comments as important distinctive features. Also, very few of the respondents seem to think that it is necessary for people from their homeplace to change dialects to be understood in Tromsø (cf. ). Respondents from Trøndelag and Western Norway provide the most comments on this question, and several state that it can be necessary to change certain words and expressions that can be hard to understand, but this does not mean that one has to let go of one’s dialect completely. The term knot (cf. Molde Citation2007) is used by some as an example of what one should not do with one’s dialect. Several of the respondents highlight the importance of maintaining one’s dialects because it reflects who one is and where one comes from. However, many of the respondents report that they have changed their dialect, mostly changes in vocabulary to more standard alternatives, which means dialect features that are close to features in the standard Eastern Norwegian dialect, in order to be understood more easily. The respondents express that one should not speak too bredt (broadly), using dialect words and expressions that are difficult to understand, but one should not speak too “purely” either by using a dialect that is close to the written language bokmål, such as levelled dialects or the Oslo dialect. There is no obvious line between knot and acceptable adjustments of the dialect, but as long as one can justify dialect changes by wanting to be understood, at least mild knot seems to be forgivable. All in all, maintaining one’s initial dialect seems to be the ideal, but if one must make a choice between maintaining a dialect and being understood, the latter appears to be more important.

The respondents express that dialect maintenance or shifting can be more or less out of one’s hands, and that this is truer for some than others. One respondent writes:

Let the language come naturally, regardless of dialect. Some change without knowing it, and others keep theirs without knowing it. Some are probably more easily influenced by language, I think.

La språket komme naturlig uansett dialekt. Noen endrer uten at de vet det og andre beholder sin uten at de vet det. Noen lar seg vel lettere påvirke av språk vil jeg tro.

The comments also indicate, more or less explicitly, that dialect shifts or changes are unwanted or that they can be followed by unwanted attention, and that this is something one must learn to accept:

Keep their dialect, it says something about where you come from, and don’t care about comments on the dialect.

Holde på dialekten sin, den sier noe om hvor du er ifra og ikke bry seg om kommentarer man får på dialekten sin.

Do not try to speak Northern Norwegian if you are not from Northern Norway. They will laugh at you.

Ikke forsøk å snakke nordlending om du ikke er det. Da ler de av deg.

I would advise them to speak and to continue to speak their dialect, but to not despair if the dialect changes.

Jeg ville råde dem til å snakke å fortsette og snakke dialekten sin, men ikke bli fortvila dersom den forandrer seg.

Furthermore, a general assumption seems to be that shifts or changes should happen “naturally” and intuitively. As one respondent puts it,

When you try to change your dialect on purpose, it rarely sounds good.

Når man begynner å prøve å endre dialekten sin med vilje, så høres det sjelden bra ut.

The respondents commonly assume that there is high acceptance in Tromsø of dialects from Western Norway, Trøndelag and Northern Norway, but that many people from Tromsø have negative attitudes towards dialects from central parts of Eastern Norway and Oslo. Indeed, in the context of Tromsø the linguistic self-confidence among the Eastern Norwegian respondents seems to be quite low (cf. ). Eastern Norwegian dialects are described as “flat” and “boring.” One respondent writes that this mindset probably builds on the opinion that søringer (southerners), usually referring to people from Eastern Norway, often think that they are better than people from Northern Norway. Other comments mention negative attitudes towards dialects that have features of Sámi and Kven/Finnish. Dialects from Finnmark are also described as less attractive. One comment mentions strong negative attitudes towards the written language Nynorsk, which is the lesser used one of the two official written languages in Norway, and towards dialects that are close to this written language.

Many of the respondents react to the use of the demonym tromsøværing in the questionnaire. They write that there is no such thing as tromsøværinger “in general”, and when asked if they feel like a tromsøværing, half answer “no” or comment on this question. Some point out that they feel like they belong in Tromsø, but not like a tromsøværing, and that this is an important distinction. According to one respondent, dialect (among other things) creates a strong and defining connection to one’s homeplace:

[I] feel [a sense of] belonging to Tromsø, but don’t know if I will ever be a tromsøværing. The connection to my homeplace created by my dialect, among other things, is too strong for that.

Føler tilhørighet til Tromsø, men vet ikke om jeg noen gang blir tromsøværing. Til det har jeg litt for sterk tilhørighet til mitt eget hjemsted, bl.a. via dialekten min.

Only tromsøværinger can become tromsøværinger, I have been told.

Bare tromsøværinger kan bli tromsøværinger, har jeg blitt fortalt.

Senjaværing.Footnote7 Perhaps “tromsøværing from other parts of the country.”

Senjaværing. Ev «innflytta tromsøværing».

5. Discussion

As mentioned in the introduction, we are interested in finding out whether speakers of Norwegian dialects who have moved to Tromsø maintain, shift or change their initial dialects, and we are interested in their attitudes towards various forms of dialect use, including dialect maintenance, shifts or changes. Our main finding is that many of the in-migrants in our study reportedly changed their first dialect, including vocabulary, often towards a perceived standard alternative. They generally explain these changes as stemming for a desire to be more easily understood, even though many do not consider it necessary to change their dialect to be understood in Tromsø.

When asked what they think people moving to Tromsø should do with their dialect, the in-migrants are divided. One group seem to be quite reluctant to change, expressing that it is important to maintain one’s initial dialect, almost at any cost. The other group seems to be less inclined to give such advice, expressing resistance to purism and normativity. Also, the Northern Norwegian in-migrants seem to be more reluctant to change than in-migrants from other parts of the country, while the Southern Norwegians and in-migrants that have lived in two or more places seem to be the least restrictive to change.

The in-migrants express that they have negative attitudes towards dialect shifts or changes, such as knot, which is generally seen as an unacceptable sociolinguistic strategy, but they seem positive in cases where such strategies favour communication or involve changing or shifting away from a more prestigious linguistic variety (e.g. an Eastern Norwegian dialect). If a decision must be made between maintaining one’s dialect and making oneself understood, the latter appears to be more important. Still, accommodating a dialect “too much” (e.g. trying to speak Northern Norwegian if one is not from Northern Norway) is perceived as ridiculous. The idea of authentic language use and language user does seem to frame the possible choices (cf. Jorung Citation2018), but what is authentic is not given for all in all contexts. Thus, the in-migrants express rather conflicting attitudes towards dialect maintenance versus dialect change. There is resistance to knot as well as purism and normativity. This shows that language attitudes and ideologies are not static, but are frames that are negotiable under changing sociolinguistic circumstances (cf. Sollid Citation2014; Rosa and Burdick Citation2016).

The in-migrants’ negative attitudes towards knot could serve as an example of the social desirability bias (cf. Garrett Citation2010, see part 3.1.). As mentioned, the social desirability bias is the tendency for people to respond to questions in ways that they perceive to be socially appropriate, which means that the respondents could be inclined to tell you about the attitudes that they think they should have. This could also be the case when one respondent writes: “Only tromsøværinger can become tromsøværinger, I have been told.”

The explanation of wanting to be understood usually relates to several more or less deliberate motivations, such as not wanting to be stigmatized, be the subject of prejudice, or be ascribed unwanted qualities or identities (Mæhlum and Røyneland Citation2009). A large number of the respondents in our survey report receiving comments on their dialect use, and some write that such comments have made them more aware of the use of uncommon dialect words that can be “difficult to understand.” Typically, people comment on dialect features that they are not used to and that mark the speaker as different in some way, and such comments often have the effect of moving attention away from what is being said towards how it is being said. The speaker can experience this as negative or frustrating, especially if it occurs frequently, and it can be perceived as a hindrance to communication. In light of this, adjusting one’s dialect, or at least avoiding the most unusual or marked features of the dialect, seems to be a tolerable sociolinguistic strategy to fit in and accommodate the new place.

We are also interested in how the in-migrants perceive attitudes towards various forms of dialect use in Tromsø. According to our findings, a common assumption is that people in Tromsø have positive attitudes towards other dialects, especially dialects from Western Norway, Trøndelag and Northern Norway, but it seems to matter where one comes from and which dialect one speaks. Our data show that some respondents have negative attitudes towards dialects with features of Sámi or Kven/Finnish, which is connected to language ideologies of purism (cf. Røyneland Citation2017) and proper Norwegian (cf. Sollid Citation2009, Citation2014). In addition, the respondents express that people in Tromsø have quite negative attitudes towards Eastern Norwegian dialects, mainly towards the “prestigious” Oslo dialect. As the capital of Norway, Oslo is positioned at the top of the hierarchy of Norwegian cities, and it can be seen as the originator of several social and cultural impulses that spread throughout the country (cf. Mæhlum et al. Citation2008). On a national level, the relationship between Oslo and Tromsø is asymmetrical in many ways, including in regard to dialect use. However, this does not mean that it is easy for people from Oslo to use their dialect when they move to other parts of the country. On a regional level, in the Northern Norwegian context, there appear to be other linguistic hierarchies where Northern Norwegian varieties may be ranked higher than the Oslo dialect (Jorung Citation2018). The Eastern Norwegian in-migrants in our survey seem to encounter both a strong regional identity when they move to Tromsø, and simultaneously the perception of Eastern Norwegians as stuck-up. This contrast between place identities is manifested, for example, in the encounter between the tromsøværing, which is a proud local patriotic person, and the søring, a term that often carries negative connotations in a Northern Norwegian context (cf. Jorung Citation2018). The strong regional identity of Northern Norway could be a result of strategic promotion of Northern Norwegian identity and culture by politicians, media and the business sector. Due to its position at the top of the hierarchy of Norwegian cities, Oslo may have less need to create a collective city identity (Jorung Citation2018). In the capital, identities are more strongly related to urbanness or whether one lives on the east side or west side (cf. Stjernholm Citation2013).

Our findings indicate that the in-migrants view the category of tromsøværing as an exclusive one. They are careful about using the demonym to refer themselves, and when they do, they seem to have a need to specify that they still regard themselves as in-migrants. The respondents express that it can seem almost impossible to be entirely included in a new community, at least as long as one speaks a different dialect. However, several state that one’s first dialect reflects who one is and where one comes from, and changing this dialect “too much” and “on purpose” is seen as an attempt to change one’s identity and as disloyal to one’s homeplace. In an increasingly populated and diverse city like Tromsø, it seems to be important to show that one still has a connection with one’s homeplace, such as by continuing to speak the dialect of that place. The respondents express that they want to be continuous, and that they want to be perceived as “the same” despite moving to a new place and experiencing social and linguistic changes. They want to be perceived as authentic, both by the tromsøværing and the people they moved away from, and they want to be recognizable as both an in-migrant and an inhabitant of the region where they used to live. Accordingly, attempts to maintain one’s initial dialect can be understood as attempts to create continuity and coherence in shifting environments.

At this point it is important to emphasize that our data does not say anything about how our respondents actually speak, and limitations of questionnaire data are also relevant for our study. The survey nevertheless points to interesting folk linguistic perspectives of dialects on the move. Also, there are some patterns that in future studies will be interesting to go deeper into, and here we would in particular point to the role of place in deliberations between sociolinguistic strategies in the context of in-migration.

6. Conclusion

In this article, we have examined the “dialect paradise” of Norway in the context of in-migration to Tromsø, looking at the experiences of speakers for whom Norwegian is their first language. Based on both quantitative and qualitative data from a questionnaire study, we have (1) looked at the respondents attitudes towards various forms of dialect use, including dialect maintenance, shifts or changes, and we have (2) looked at how the in-migrants perceive attitudes in Tromsø towards various forms of dialect use. The findings indicate that it is seen as ideal to maintain one’s initial dialect and that knot is generally perceived as an unacceptable strategy. However, the respondents also show resistance to language ideologies of purism and normativity. Most of them reportedly changed their own initial dialect, and changing or shifting the dialect is perceived as a tolerable sociolinguistic strategy to fit in and accommodate the new place. The in-migrants navigate and relate to frames on different levels created by language ideologies, and they negotiate situations in which they experience conflicting ideologies. The assumptions evident in the survey responses indicate a high degree of acceptance of other dialects in Tromsø, but where one comes from and which dialect one speaks seem to matter. In particular, there are quite negative attitudes towards dialects from central parts of Eastern Norway and from Oslo. The Eastern Norwegian in-migrants encounter a strong regional place identity when they move to Tromsø, including the idea of the tromsøværing, which differs from the way they connect and identify with their own homeplace. The in-migrants see it as almost impossible to be entirely included in a new community as long as they have a different dialect than the local one. Nevertheless, it is important for them to be recognizable and authentic, both as an in-migrant (to the tromsøværing) and as an inhabitant of the place from which they moved (to the people of that area).

Acknowledgement

We warmly thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, which has helped us develop our arguments. Any shortcomings or errors are nevertheless our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Hvilke(n) dialekt(er) snakker du?

2 Hvordan vil du beskrive din måte å snakke på?

3 Original comment: blandingsdialekt. Kan skifte mellom Tromsø dialekt og Stavanger dialekt, men Tromsø dialekten vil være en blandingsdialekt.

4 Here the respondent refers to dialect variation in present tense of the verb komme (infinitive), i.e. “come”. In Trondheim, kjem is more frequently used than kommer (cf. Hårstad Citation2010). The latter is probably a sociolinguistically more noticeable alternative in Trondheim than in Tromsø.

5 Original comment: Jeg blander ikke, men varierer sterkt innenfor trondhjemsken kjem/kommer osv etter hvem jeg snakker med.

6 Original comment: Kun én dialekt, men innslag av ord fra andre dialekter.

7 The demonym senjaværing refers to a person from island Senja in Finnmark and Troms County.

References

- Aalen, Odd O. 1998. Innføring i statistikk med medisinske eksempler. Oslo: Ad Notam Gyldendal.

- Akselberg, Gunnstein. 2008. “‘Kor pent bergensk snakkar du?’. Ei gransking av sjølvrapporterte språkdata til avisa Bergens Tidende si heimeside, bt.no.” Målbryting 9: 149–166.

- Albarracin, Dolores, Blair T. Johnson, and Mark P. Zanna. 2014. The Handbook of Attitudes. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Allport, Gordon W. 1954. “The Historical Background of Modern Social Psychology.” In Handbook of Social Psychology, Volume 1: Theory and Method, edited by Gardner Lindzey, 3–56. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Atteslander, Peter. 2005. “Schriftliche Befragung.” In Sociolinguistics: An International Handbook of the Science of Language and Society, vol. 2, edited by Ulrich Ammon, Norbert Dittmar, Klaus J. Mattheier, and Peter Trudgill, 1063–1076. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Best, Samuel J., and Brian S. Krueger. 2004. Internet Data Collection. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Brunstad, Endre. 2001. “Det reine språket. Om purisme i dansk, svensk, færøysk og norsk.” Unpublished dr.art. diss., University of Bergen.

- Brunstad, Endre. 2003. “Purismeomgrepet gjennom to tusen år.” In Purt og reint. Om purisme i dei nordiske språka, vol. 15, edited by H. Sandøy, R. Brodersen, and E. Brunstad, 37–64. Skrifter frå Ivar Aasen-instituttet. Volda: Høgskulen i Volda.

- Bull, Tove. 1996. “Tromsø bymål.” In Nordnorske dialektar, edited by Ernst Håkon Jahr, and Olav Skare, 175–179. Oslo: Novus forlag.

- Chambers, J. K., and Peter Trudgill. 1998 [1980]. Dialectology. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Coupland, Nikolas. 2014. “Sociolinguistic Change, Vernacularization and Broadcast British Media.” In Mediatization and Sociolinguistic Change, edited by Jannis Androutsopoulos, 67–96. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Coupland, Nikolas, and Adam Jaworski. 2012. “Sociolinguistic Perspectives on Metalanguage: Reflexivity, Evaluation and Ideology.” In Metalanguage: Social and Ideological Perspectives, edited by Adam Jaworski, Nikolas Coupland, and Dariusz Galasinski, 15–51. Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter.

- Eichhoff, Jürgen. 1982. “Erhebung von Sprachdaten Durch Schriftliche Befragung.” In Dialektologie. Ein Handbuch zur Deutschen und Allgemeinen Dialektforschung, vol. 1, edited by Werner Besch, Werner Knoop, Wolfgang Putschke, and Herbert Ernst Wiegang, 549–554. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Garrett, Peter. 2010. Attitudes to Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Garrett, Peter, Angie Williams, and Nikolas Coupland. 2003. Investigating Language Attitudes: Social Meanings of Dialect, Ethnicity and Performance. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Grefenstette, Gregory. 2002. “The WWW as a Resource for Lexicography.” In Lexicography and Natural Language Processing – A Festschrift in Honour of B.S.T. Atkins, edited by Marie-Hélène Corréard, and Beryl T. Atkins, 199–215. Huddersfield: EURALEX.

- Hårstad, Stian. 2008. “Store tal frå trondheimsk tale: Metodologisk drøfting av ei nettbasert dialektgransking.” Målbryting 9: 127–147.

- Hårstad, Stian. 2010. “Unge språkbrukere i gammel by: En sosiolingvistisk studie av ungdoms talemål i Trondheim.” PhD diss., Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

- Haugen, Ragnhild. 2004. “Språk og språkhaldningar hjå ungdomar i Sogndal.” PhD diss., University of Bergen.

- Irvine, Judith T. 1989. “When Talk Isn’t Cheap: Language and Political Economy.” American Ethnologist 16: 248–267.

- Irvine, Judith, and Susan Gal. 2000. “Language Ideology and Linguistic Differentiation.” In Regimes of Language: Ideologies, Politics and Identities, edited by Paul V. Kroskrity, 35–83. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

- Jahr, Ernst Håkon, and Carol Janicki. 1995. “The Function of the Standard Variety: A Contrastive Study of Norwegian and Polish.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 115: 25–45.

- Johnson, Keith. 2008. Quantitative Methods in Linguistics. Malden: Blackwell.

- Jorung, Sandra Skaflem. 2018. “‘Søringer’ på vandring i nord. En sosiokulturell-lingvistisk studie av språklig identitet og tilhørighet hos fire flyttere fra Oslo til Tromsø.” Master’s thesis, UiT The Arctic University of Norway.

- Knoop, Ulrich, Wolfgang Putschke, and Herbert E. Wiegand. 1982. “Die Marburger Schule: Entstehung und frühe Entwicklung der Dialektgeographie.” In Dialektologie. Ein Handbuch zur Deutschen und Allgemeinen Dialektforschung, vol. 1, edited by Werner Besch, Werner Knoop, Wolfgang Putschke, and Herbert Ernst Wiegang, 38–91. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Labov, William. 1966. The Social Stratification of English in New York City. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

- Lambert, W., R. Hogdson, R. Gardner, and S. Fillenbaum. 1960. “Evaluational Reactions to Spoken Languages.” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 60 (1): 44–51. doi:10.1037/h0044430.

- Mæhlum, Brit. 2011. “Det ureine språket: Forsøk på en kultursemiotisk og vitenskapsteoretisk analyse.” Maal og Minne 1: 1–31.

- Mæhlum, Brit, and Unn Røyneland. 2009. “Dialektparadiset Norge – en sannhet med modifikasjoner.” In I mund og bog: 25 artikler om sprog tilegnet Inge Lise Pedersen på 70-årsdagen d. 5. juni 2009, edited by Henrik Hovmark, Iben Stampe Sletten, and Asgerd Gudiksen, 219–231. Copenhagen: Copenhagen University.

- Mæhlum, Brit, and Unn Røyneland. 2018. “Dialekt, indeksikalitet og identitet. Tilstandsrapport fra provinsen.” In Dansk til det 21. århundrede – sprog og samfund, edited by Tanya K. Christensen, Christina Fogtman, Torben Juel Jensen, Martha Sif Karrebæk, Marie Maegaard, Nicolai Pharao, and Pia Quist, 247–262. Copenhagen: U Press.

- Mæhlum, Brit, Unn Røyneland, Gunnstein Akselberg, and Helge Sandøy. 2008. Språkmøte: Innføring i sosiolingvistikk. 2nd ed. Oslo: Cappelen Akademisk.

- Molde, Else B. 2007. Knot. Omgrepet, definisjonane og førestellingane. Unpublished master's thesis. Bergen: Universitetet i Bergen.

- Nesse, Agnete, and Hilde Sollid. 2010. “Nordnorske bymål i et komparativt perspektiv.” Maal og Minne 102 (1): 137–158.

- Omdal, Helge. 1994. “Med språket på flyttefot. Språkvariasjon og språkstrategier blant setesdøler i Kristiansand.” PhD diss., Uppsala University.

- Ommeren, Rikke van. 2016. “Den flerstemmige språkbrukeren. En sosiolingvistisk studie av norske bidialektale.” PhD diss., Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

- Oppenheim, B. 1982. “An Exercise in Attitude Measurement.” In Social Psychology: A Practical Manual, edited by Glynis M. Breakwell, Hugh Foot, and Robin Gilmour, 38–56. London: Macmillan.

- Oppenheim, A. N. 1992. Questionnaire Design, Interviewing, and Attitude Measurement. London: Pinter.

- Preston, Dennis. 1993. “The Uses of Folk Linguistics.” International Journal of Applied Linguistics 3 (2): 181–259.

- Rosa, Jonathan, and Christa Burdick. 2016. “Language Ideologies.” In The Oxford Handbook of Language and Society, edited by Ofelia García, Nelson Flores, and Massimiliano Spotti, 1–25. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190212896.013.15.

- Røyneland, Unn. 2009. “Dialects in Norway: Catching Up With the Rest of Europe.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 196–197: 7–30. doi:10.1515/IJSL.2009.015.

- Røyneland, Unn. 2017. “Hva skal til for å høres ut som du hører til? Forestillinger om dialektale identiteter i det senmoderne Norge.” In Ideologi, Identitet, Intervention. Nordisk Dialektologi 10, edited by Jan-Ola Östman, Caroline Sandström, Pamela Gustavsson, and Lisa Södergård, 91–107. Helsingfors: Helsingfors universitet.

- Sarnoff, I. 1970. “Social Attitudes and the Resolution of Motivational Conflict.” In Attitudes, edited by Marie Jahoda, and Neil Warren, 279–284. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin.

- Schieffelin, Bambi B., Kathryn Ann Woolard, and Paul V. Kroskrity. 1998. Language Ideologies: Practice and Theory. Vol. 16, Oxford Studies in Anthropological Linguistics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Silverstein, Michael. 1998. “The Uses and Utility of Ideology.” In Language Ideologies: Practice and Theory. Vol. 16, Oxford Studies in Anthropological Linguistics, edited by Bambi B. Schieffelin, Kathryn Ann Woolard, and Paul V. Kroskrity, 123–145. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sollid, Hilde. 2009. “Utforsking av nordnorske etnolekter i et faghistorisk lys.” Maal og Minne 2: 147–169.

- Sollid, Hilde. 2014. “Hierarchical Dialect Encounters in Norway.” Acta Borealia 31 (2): 111–130. doi:10.1080/08003831.2014.967969.

- Sollid, Hilde. 2019. “Språklig mangfold som språkpolitikk i klasserommet.” Målbryting 10: 1–16. doi:10.7557/17.4807.

- Stjernholm, Karine. 2013. “Stedet velger ikke lenger deg, du velger et sted. Tre artikler om språk i Oslo.” PhD diss., University of Oslo.

- Stjernholm, Karine, and Ingunn Indrebø Ims. 2014. “Om bruk av Oslo-testen for å undersøke oslomålet.” Norsk lingvistisk tidsskrift 32: 100–129.

- Thomas, Georg. 1991. Linguistic Purism. London - New York: Longman.

- Trudgill, Peter. 2002. Sociolinguistic Variation and Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Wiggen, Geirr. 1995. “Norway in the 1990s: A Sociolinguistic Profile.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 115: 47–83.

![Figure 7. “Do you think tromsøværinger generally like the dialect of your homeplace? [Tror du tromsøværinger generelt liker dialekten ved hjemstedet ditt?]” The figure shows percentage distribution according to place of origin (n = 278).](/cms/asset/2a61ca0b-891f-4df1-88df-a428c0a06702/sabo_a_1911209_f0007_ob.jpg)