Abstract

Not much is known about factors influencing hypertension management in patients with ischaemic heart disease (IHD). Therefore, the aim of the study was to assess factors influencing hypertension management in patients hospitalized due to IHD. We reviewed hospital records of 1051 consecutive patients with a discharge diagnosis of myocardial infarction (MI; n = 290), unstable angina (n = 247), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI; n = 259) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG; n = 255) who were hospitalized at three university (n = 533) or three community (n = 518) cardiac departments. During the follow‐up interview (6–18 months after discharge) 70.2% of study participants fulfilled the criteria for a diagnosis of hypertension. Hypertension had not been diagnosed during index hospitalization in 17.5% of hypertensive participants. Overall, 7.1% of hypertensives were not treated with any blood pressure lowering agent. Irregular health checks (odds ratio, OR, 16.3, 95% confidence interval, CI, 4.1–64.0), alcohol drinking (OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.5–7.0), unstable angina (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.3–5.8), hypertension awareness (OR 0.2, 95% CI 0.1–0.5) and blood pressure lowering drugs prescribed at discharge (OR 0.08, 95% CI 0.03–0.19) were significantly related to the probability of not being on antihypertensive medication. High blood pressure (⩾140/90 mmHg) was found in 68.9% of hypertensives; older age (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.0–1.6) and hypertension awareness (OR 0.6, 95% 0.3–1.0) were the only significant predictors of uncontrolled hypertension. Among treated participants with uncontrolled hypertension, 33.4% were on monotherapy, 66.6% were on combination therapy, 25.5% were on three or more drugs and 14.7% were on combination of three or more drugs with diuretic. Conclusions. Hypertension management in the secondary prevention of IHD is not satisfactory. Age and hypertension awareness are the main factors related to the quality of blood pressure control in the post‐discharge period.

Introduction

The current status of hypertension management in the general population is far from being satisfactory. Large studies have shown that the rate of controlled blood pressure (BP) among patients with hypertension does not exceed 30% worldwide Citation[1–6], although safe and effective therapies for hypertension are readily available, and the importance of obtaining optimal BP control through the use of these therapies is being increasingly recognized. Several factors have been indicated as possibly responsible for poor hypertension management in the general population Citation[1], Citation[3], Citation[7–9].

Recently published results from Europe and North America showed that about half of ischaemic heart disease (IHD) patients have their BP >140/90 mmHg Citation[10–14]. In addition, a cross‐sectional survey conducted in France showed that about 30% of patients admitted for unstable angina or myocardial infarction (MI) leave hospital with uncontrolled hypertension Citation[15]. Although hypertensive subjects with IHD are at a much higher risk when compared with their counterparts without IHD, little is known about factors influencing hypertension management in patients who have undergone hospitalization due to IHD. So far, no study has specifically addressed the issue of hypertension control in patients after coronary angioplasty or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Moreover, no study assessed the frequency of undiagnosed and untreated hypertension in IHD patients. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate factors influencing hypertension management during and after hospitalization due to IHD.

Methods

The study design was similar to that of the EUROASPIRE surveys Citation[10]. We reviewed hospital records of 1051 consecutive patients hospitalized between 1 July 1996 and 30 March 1999 in three university (n = 533) and three community (n = 518) hospitals. The criterion of inclusion in the study was the discharge diagnosis of:

Acute MI (first or recurrent, no prior percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or CABG, n = 290);

Unstable angina (first or recurrent, no prior MI, PCI or CABG, n = 247);

PCI (first, no prior CABG, n = 259);

First CABG (n = 255).

The six cardiac departments served the area of the city of Kraków and its province (1.2 million inhabitants). In cases of patients with more then one hospitalization during the study period, only the first admission was considered. Patients with incomplete medical records, those over 70 years old and those not surviving to hospital discharge were not included in the analysis. All charts were abstracted by trained reviewers using a standardized data‐collection form, including information about demographics, history of IHD, coronary risk factors and on‐discharge treatment.

The follow‐up interview took place 6–18 months after discharge (from 1 October 1997 to 30 May 2000). During the interview, personal and demographic details, history of IHD, smoking status, height, weight, BP, fasting glucose, plasma lipids and a list of current medications were obtained. Treatment rates are reported for all patients, without excluding those with contraindications to specific antihypertensive drugs.

BP was measured twice using a sphygmomanometer. Both measurements were performed in standardized conditions, i.e. with the patient seated, at room temperature, between 07.30 and 10.00 h, after at least 30 min without eating or smoking and after a 10‐min rest. The right arm was used for measurements whenever possible. BP for individual participants was calculated as the average of the two readings.

Participants were considered hypertensive if they had high BP (⩾140/90 mmHg) during the follow‐up interview or if they were treated with antihypertensive drugs at that time and were diagnosed as having hypertension during index hospitalization. The patients were considered having undiagnosed hypertension if they had hypertension (as defined above) and it was not diagnosed during index hospitalization. According to official Polish guidelines controlled hypertension was defined as systolic BP <140 mmHg and diastolic BP <90 mmHg during the interview in participants with hypertension (as defined above). The patients were considered having treated hypertension if they had hypertension (as defined above) and were prescribed at least one BP lowering drug (even if it was prescribed for treatment of stable angina, heart failure etc). Beta‐blockers, angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, calcium antagonists, diuretics, angiotensin II receptor blockers, vasodilatators, alpha‐blockers and central acting agents were considered BP lowering drugs. Spironolactone was considered a diuretic.

A fasting venous blood sample was obtained for plasma lipid and glucose measurements between 07.30 and 08.30 h. Total cholesterol concentrations were assessed using a Technicon RA‐1000 analyser. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as total cholesterol level ⩾5.2 mmol/l and/or being on a lipid‐lowering drug at the time of the interview (we used cholesterol value of 5.2 mmol/l [instead of 5.0 mmol/l] because at the time of conducting the present study the value of 5.2 mmol/l was recommended as a cut‐off for hypercholesterolemia in Poland). Body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by square of height in meters) was used as an index of obesity. Practice setting was defined on the basis of the patient's declaration. The study protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee.

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using the Statistica 5.5 software. Categorical variables were reported as percentages, whereas continuous variables as means±SD. The Pearson's χ2 test was applied to all categorical variables. Normally distributed continuous variables were compared using Student's t‐test. The Mann–Whitney U‐test was used in case of variables without normal distributions. A two‐tailed p‐value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. A multivariate analysis, consisting of a logistic regression, was performed with the use of all variables (for untreated and uncontrolled hypertension). As it is improbable that BP lowering drugs prescription at discharge or hypertension awareness 6–18 months after discharge could influence diagnosis of hypertension during the index hospitalization, we did not include these variables into the multivariable analysis when undiagnosed hypertension was the dependent variable. Items with the highest p‐values were sequentially removed and a new logistic model was defined without the eliminated variable. This operation was continued until all remaining variables had p‐values <0.05.

Results

Overall, 1051 patients were considered to fulfil the study entry criteria. Of the 1051 patients, 845 (80.4%) agreed to participate in the interview 6–18 months (mean 13.9±4.7 months; median 12.9 months) after discharge. A possible selection bias in the formation of this study population was examined by comparing it with respect to age, sex, risk factors, and the rate of BP lowering drugs prescribed at discharge with 206 patients on whom we had no interview data. These comparisons did not reveal any statistically significant differences with respect to all the above factors except for the frequency of beta‐blockers (65.7% in responders vs 57.8% in non‐responders; p<0.05) and diuretics (15.0% vs 20.6%; p<0.05) prescribed at discharge. We also compared the attendance rates between the discharge diagnosis groups showing a slight but statistically significant bias (p<0.05), characterized by a somewhat higher attendance rate in the PCI group (79.3%, 76.9%, 87.6% and 77.7% for MI, unstable angina, PCI and CABG group, respectively).

The average BP at the interview was 138.7±21.5 mmHg for systolic and 84.1±11.5 mmHg for diastolic. O845 participants, 408 (48.3%) had high BP (⩾140/90 mmHg) during the follow‐up interview; high BP was more frequent in the patients who had been diagnosed as having hypertension during index hospitalization (60.4% vs 30.4% in diagnosed vs not‐diagnosed, respectively; p<0.0001).

Overall, 593 (70.2%) participants met the criteria, as defined in the Methods section, for having hypertension. The average BP at the interview in hypertensive participants was 145.7±21.0 mmHg (systolic) and 87.2±11.4 mmHg (diastolic) whereas in non‐hypertensive ones (n = 252) it was 122.3±11.3 and 76.8±8.0 mmHg, respectively. Participants with hypertension were older, more often had diabetes or obesity, and less often were smokers. Women were more likely to have hypertension ().

Table I. Characteristics of participants with and without hypertension (as defined in the methods section).

Diagnosis of hypertension

In 104 (17.5%) of 593 hypertensive participants, the diagnosis of hypertension had not been made during index hospitalization. Sex, education, diabetes and the history of MI prior to index hospitalization were related to the rate of undiagnosed hypertension in univariate analysis (). Patients with detected hypertension during index hospitalization were more often prescribed BP lowering drugs at discharge and more often were aware of having hypertension at the time of follow‐up screening (). Male sex, absence of diabetes and the positive history of MI were independently related to having undiagnosed hypertension ().

Table II. Proportions of patients with undetected, untreated and uncontrolled hypertension according to demographic, healthcare and cardiovascular risk factors.

Table III. Independent predictors of undetected, untreated and uncontrolled hypertension in hypertensive ischaemic heart disease patients (n = 593).

Treatment of hypertension

Of 593 hypertensives, 185 (31.2%), 230 (38.8%), 117 (19.7%), 17 (2.9%) and two (0.3%) participants were taking one, two, three, four and five BP lowering drugs, respectively and 42 (7.1%) were not treated with any BP lowering drug at the time of the interview. Hypertensives who had not been diagnosed as having hypertension during the index hospitalization were more frequently untreated at the time of follow‐up interview (4.5% among diagnosed hypertensives vs 19.2% among undiagnosed ones; p<0.0001). Sex and hospital settings were predictors of untreated hypertension in univariate, but not in multivariate analysis (Tables and ). Irregular health check was related to being untreated (); however, no significant difference in the rate of untreated hypertension was found between other practice settings (hospital outpatient clinic vs general practitioner vs private cardiology practice). Heavy alcohol drinking, discharge diagnosis of unstable angina, irregular health check, BP lowering therapy at discharge and hypertension awareness were independently related to the probability of patient being on antihypertensive medication at the time of follow‐up interview ().

BP control

Of 593 hypertensives, 407 participants (68.9%) had uncontrolled hypertension during interview (BP ⩾140/90 mmHg), of whom 355 (87.2%) had uncontrolled systolic BP and 239 (58.7%) diastolic BP. Older hypertensives was found to have uncontrolled hypertension significantly more often when compared with those of age below 60 years (). Hypertension awareness and age were the only independent predictors of well‐controlled hypertension in multivariate analysis ().

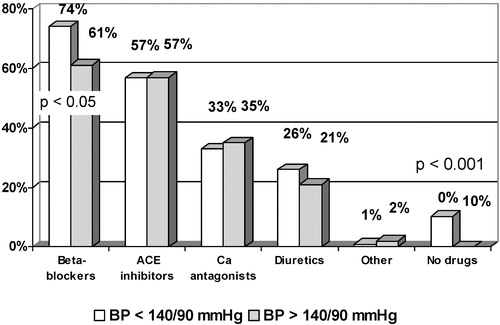

All hypertensives with BP below 140/90 mmHg at the interview were taking BP lowering drugs, but 10.3% of those with high BP were without any antihypertensive therapy (p<0.0001) (). Among treated participants with uncontrolled hypertension 33.4% were on monotherapy, 66.6% were on combination therapy, 25.5% were on three or more BP lowering drugs and 14.7% were on three or more drug combination with diuretic. Among hypertensives with BP below 140/90 mmHg 34.2%, 65.8%, 23.4% and 15.1% were on monotherapy, combination therapy, combination therapy consisting of at least three drugs, and on three or more drugs combined with diuretic, respectively.

Discussion

Definition of hypertension

According to the above definition, hypertension was present in 70.2% of patients who attended the follow‐up visit 6–18 months after hospitalization. This percentage is higher than in the general population, as hypertension is a risk factor for IHD. In the Polish general population, 35–45% of subjects are hypertensive Citation[4]. The estimated prevalence of hypertension may be associated with an error related to different criteria of hypertension diagnosis applied in different hospitals participating in the study. The present results may have also been influenced by the variation in BP levels, which might have led to a misclassification of patients as hypertensive/normotensive.

In most studies assessing the prevalence of hypertension in the general population, elevated BP and/or the intake of BP lowering drugs was used for hypertension diagnosis Citation[1–5]. These studies did not take into account the error associated with the intake of BP lowering drugs for reasons other than hypertension (angina, heart failure, history of MI, peripheral artery disease), because the prevalence of these conditions is much lower than that of hypertension. In the population of the present study, this definition could not be applied since 88.6% of subjects were taking at least one drug with BP lowering potential. On the other hand, the diagnosis of hypertension on discharge from the hospital could not qualify for hypertensive or normotensive group, as 30.4% of patients without a diagnosis of hypertension during hospitalization had BP >140/90 mmHg 6–18 months after discharge, thus qualifying them for the hypertensive group. It should also be noted that in over 5% of subjects with no hypertension diagnosis on discharge, three to four BP lowering drugs were nevertheless prescribed. Our results indicate that physicians' diagnosis of hypertension should be considered with caution when used to identify IHD patients with hypertension.

The above definition of hypertension does not include patients with a history of elevated BP (or even hypertension diagnosis), who had normal (<140/90 mmHg) BP during the control visit and did not take antihypertensive medication. Similarly, such patients were not considered hypertensive in other large epidemiological studies Citation[1–5]. Subjects with elevated BP during hospitalization but without hypertension diagnosis at discharge were considered to have hypertension if BP was ⩾140/90 mmHg during follow‐up visit. If, however, in these subjects BP was below 140/90 mmHg it can be reasonably assumed that no diagnosis of hypertension at discharge was correct. This is because elevated BP values in patients with acute coronary episodes, or in the period close to percutaneous or surgical coronary intervention, do not always reflect hypertension in everyday conditions and cannot be used for hypertension diagnosis. The hypertension definition used in the present study does not include the subjects in whom hypertension diagnosis was missing in the discharge letter, who during control visit were on antihypertensive medication and had normal BP level. It can thus be assumed that the percentage of patients with IHD and undiagnosed hypertension may be even higher than the observed 17.5%.

Diagnosis of hypertension

Women were found to have hypertension more frequently compared to men in the present analysis. Probably, the higher mean age of women can explain this difference.

An interesting subgroup of the present study was the patients with hypertension that were not diagnosed during index hospitalization. Their number may be slightly overestimated, as in some of them hypertension may have developed in the post‐discharge period; still, the proportion of patients with new onset hypertension over 6–18 months may be expected not to exceed a few per cent Citation[16]. In our study, 30% of patients not diagnosed as having hypertension during index hospitalization had BP ⩾140/90 mmHg at the follow‐up screening. In some instances, hypertension may have been actually diagnosed during hospitalization and this fact was not recorded in patients' charts, but such situation can hardly be considered correct. Another reason for such a high rate of undiagnosed hypertension in our analysis could be the white coat hypertension. As the present study was not designed to estimate the frequency of the white coat hypertension in the study population, we can only speculate about its impact on the observed frequency of undiagnosed hypertension.

Surprisingly, the history of MI prior to index hospitalization was a predictor of undetected hypertension. In contrast to previous reports Citation[3] on non‐IHD hypertensives, age was not related to the frequency of undetected hypertension in our analysis. This may be due to exclusion of patients aged over 70. On the other hand, sex and diabetes are independently associated with diagnosis of hypertension in both IHD and non‐IHD hypertensives Citation[3].

Untreated hypertension

We showed that factors related to the frequency of untreated hypertension may be different when compared to non‐IHD hypertensives Citation[3]. Discharge diagnosis of unstable angina could be associated with a higher frequency of untreated hypertension, because some antihypertensive drugs (especially beta‐blockers and ACE inhibitors) are recommended in hypertensive as well as in non‐hypertensive post‐infarction patients. In a previous report, we showed that hospitalization in a university hospital is related to better lipid management in the post‐discharge period Citation[17]. In the present analysis, hospitalization in a university hospital was not independently related to the quality of hypertension management. The above findings support hypothesis that new treatments are used more quickly in university hospitals (at the time of follow‐ups, statins were still considered a new lipid‐lowering drugs group, whereas no such progress had been made in the hypertension pharmacotherapy).

BP control

The principal finding of this study is that despite evidence that antihypertensive therapy improves prognosis, an important portion of patients hospitalized in six cardiology departments with acute or chronic IHD failed to receive proper evaluation and treatment for hypertension during hospitalization as well as after discharge. Almost one‐third of participants without diagnosis of hypertension during index hospitalization were found to have high BP during the follow‐up interview. On the other hand, only one‐third of hypertensive participants had BP at goal (<140/90 mmHg). The European and American guidelines recommend combination therapy when monotherapy fails to control hypertension Citation[18], Citation[19]. Low‐dose combination therapy may even be considered the first step in treating hypertensive patients, especially those with high BP values. Moreover, international guidelines stress the lack of diuretic treatment as a major cause of refractory hypertension. In light of these recommendations, underuse of combination therapy was observed in the study population. Among treated participants with uncontrolled hypertension, only a quarter received at least three‐drug combination therapy 6–18 month after hospitalization due to IHD, and only every seventh patient at least three‐drug combination therapy with a diuretic. Suggestions about metabolic side‐effects of diuretics had probably refrained clinicians from using them more frequently. High systolic BP appears to be an independent predictor of cardiovascular outcome in patients after hospitalization due to acute coronary event Citation[15]. Our results are in concordance with previous report, which showed that the rate of systolic BP control is lower when compared with diastolic BP in patients without IHD Citation[20]. Asmar et al. in their pioneer paper showed that control of BP using only diastolic BP criteria may not fully reverse arterial alteration associated with hypertensive vascular disease Citation[21].

In the whole group of patients with hypertension, only 31.1% had BP below 140/90 mmHg at the time of interview. In the group of those receiving antihypertensive medication, only 33.5% had BP adequately controlled (<140/90 mmHg). In the general population of Poland, the percentage of patients with adequate BP control is much lower Citation[4] but given that patients with IHD represent a group with a very high cardiovascular risk, the above results cannot be considered satisfactory. Actually, according to the recent European guidelines, the antihypertensive treatment in this very high‐risk population should be initiated even if BP remains within high normal range Citation[19]. Among BP lowering drugs beta‐blockers were used most frequently. This finding is consistent with a number of European, US and Polish recommendations that identify beta‐blockers as the preferred first‐line agents for hypertensive subjects with IHD Citation[22–24]. A possibility cannot also be excluded that a significant proportion of our patients received beta‐blockers solely because of IHD and regardless of their BP levels.

Although age was one of the most important factors related to the control of hypertension in our as well as in the other analyses Citation[1], Citation[3], Citation[7–9], Citation[14], education and gender do not seem to be significantly related to the frequency of achieving BP goal in IHD hypertensives below the age of 70. In contrast to our analysis, Amar et al. Citation[25] found classic risk factors and gender to be related to the control of hypertension; however, entry criteria and study definition of hypertension were different in their analysis. Although diabetes was related to more frequent diagnosis of hypertension during index hospitalization, unexpectedly it was not associated with better BP control, despite published recommendations suggesting that these patients should be particularly well controlled with the target even lower than BP below 140/90 mmHg. In univariate analysis, as well as after multiple adjusting, we found no differences between the study sites (hospital outpatient clinic vs general practitioner vs private cardiology practice) in adequacy of BP management. None of the three systems of care performed well in managing hypertension.

It has been emphasized that control of hypertension could be increased if physicians improved the process of care Citation[26]. Most studies have focused on patients' non‐compliance with recommended therapies and have not examined the way in which physicians actually treat patients with hypertension. However, in 50% of hospitalized patients studied by de Macedo et al. Citation[27] extemporaneously prescription of antihypertensive medication was not associated with maintained antihypertensive treatment. In the study of Berlowitz et al. Citation[28], physicians did not increase medications during about three‐quarters of visits in which elevated BP values were recorded. Indeed, our results provide evidence that even in hospitalized high‐risk patients, hypertension is not always diagnosed. Although we did not assess patient adherence, it is improbable that patient non‐adherence alone could explain the failure of physicians to diagnose and initiate or advance therapy appropriately Citation[29]. It was shown that an important reason why physicians do not treat hypertension more aggressively is that they are willing to accept an elevated BP (especially systolic) in their patients Citation[30], Citation[31].

The study results indicate that hypertension treatment in the secondary prevention of IHD is not satisfactory. Moreover, these data provide further evidence that poor hypertension management is common in a variety of healthcare settings. Although most patients receive BP lowering drugs, still a large proportion of them have elevated BP values. An improvement in the efficacy of implementation of secondary prevention of IHD is thus mandatory. Our results also show that factors related to the quality of hypertension management in IHD patients may be somewhat different when compared with hypertensives without IHD.

Conclusions

Hypertension management in the secondary prevention of IHD is not satisfactory. Age and hypertension awareness are the main factors related to the quality of BP control in the post‐discharge period. There is a considerable potential to achieve further reduction in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in IHD hypertensives.

References

- Hyman D. J., Pavlik V. N. Characteristics of patients with uncontrolled hypertension in the United States. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 479–486

- Psaty B. M., Manolio T. A., Smith N. L., Heckbert S. R., Gottdiener J. S., Burke G. L., et al. Time trends in high blood pressure control and the use of antihypertensive medications in older adults. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162: 2325–2332

- Maziak W., Keil U., Doring A., Hense H. W. Determinants of poor hypertension management in community. J Hum Hypertens 2003; 17: 215–217

- Rywik S. L., Davis C. E., Pajak A., Broda G., Folsom A. R., Kawalec E., et al. Poland and U.S. collaborative study on cardiovascular epidemiology hypertension in the community: Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the Pol‐Monica Project and the U.S. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Ann Epidemiol 1998; 8: 3–13

- Benitez M., Codina N., Dalfo A., Vila M. A., Escriba J. M., Senar E., et al. Control of blood pressure in a population of patients with hypertension and in a subgroup with hypertension and diabetes: Relationship with characteristics of the health care center and the community. Aten Primaria 2001; 28: 373–80

- Sharma A. M., Wittchen H. U., Kirch W., Pittrow D., Ritz E., Goke B., et al. High prevalence and poor control of hypertension in primary care: Cross‐sectional study. J Hypertens 2004; 22: 479–486

- Knight E. L., Bohn R. L., Wang P. S., Glynn R. J., Mogun H., Avorn J. Predictors of uncontrolled hypertension in ambulatory patients. Hypertension 2001; 38: 809–814

- He J., Muntner P., Chen J., Roccella E. J., Streiffer R. H., Whelton P. K. Factors associated with hypertension control in the general population of the United States. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162: 1051–1058

- Llyod‐Jones D. M., Evans J. C., Larson M. G., Levy D. Treatment and control of hypertension in the community: A prospective analysis. Hypertension 2002; 40: 640–646

- Boersma E., Keil U., De Bacquer D., De Backer G., Pyorala K., Poldermans D., et al. EUROASPIRE I and II Study Groups. Blood pressure is insufficiently controlled in European patients with established coronary heart disease. J Hypertens 2003; 21: 1831–1840

- Flanagan D. E., Cox P., Paine D., Davies J., Armitage M. Secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in primary care: A healthy heart initiative. QJM 1999; 92: 245–250

- Pearson T. A., Peters T. D., Feury D. Comprehensive risk reduction in coronary patients: Attainment of goals of the AHA Guidelines in U.S. patients. Circulation 1997; 96((8S))733–I

- Lawlor D. A., Whincup P., Emberson J. R., Rees K., Walker M., Ebrahim S. The challenge of secondary prevention for coronary heart disease in older patients: Findings from the British Women's Heart and Health Study and the British Regional Heart Study. Fam Pract 2004; 21: 582–586

- Tonstad S. D., Furu K., Rosvold E. O., Skurtveit S. Determinants of control of high blood pressure. The Oslo Health Study. 2000–2001. Blood Press 2004; 13: 343–349

- Amar J., Chamontin B., Ferrieres J., Danchin N., Grenier O., Cantet C. Hypertension control at hospital discharge after acute coronary event: Influence on cardiovascular prognosis – the PREVENIR study. Heart 2002; 88: 587–591

- Vasan R. S., Larson M. G., Leip E. P., Kannel W. B., Levy D. Assessment of frequency of progression to hypertension in non‐hypertensive participants in the Framingham Heart Study: A cohort study. Lancet 2001; 358: 1682–1686

- Kawecka‐Jaszcz K., Jankowski P., Pająk A. Determinants of appropriate lipid management in patients with ischaemic heart disease. Cracovian Program for Secondary Prevention of Ischaemic Heart Disease. Intern J Cardiol 2003; 91: 15–23

- Chobanian A. V., Bakris G. L., Black H. R., Cushman W. C., Green L. A., Izzo J. L. Jr. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention., Detection., Evaluation., and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 289: 2560–2572

- Guidelines Committee. 2003 European Society of Hypertension–European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens 2003; 21: 1011–1053

- Mancia G., Grassi G. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure control in antihypertensive drug trials. J Hypertens 2002; 20: 1461–1464

- Asmar R., Benetos A., London G., Hugue C., Weiss Y., Topouchian J., et al. Aortic distensibility in normotensive, untreated and treated hypertensive patients. Blood Press 1995; 4: 48–54

- Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. Recommendations of the Second Joint Task Force of European and other Societies on Coronary Prevention. Eur Heart J 1998; 19: 1434–1503

- ACC/AHA Guidelines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction). J Am Coll Cardiol 1996; 28: 1328–1428

- Kawecka‐Jaszcz K., Januszewicz W., Rywik S., Sznajderman M. Nadciśnienie tętnicze pierwotne. Kardiol Pol 1997; XLVI((Suppl I))86–97

- Amar J., Chamontin B., Genes N., Cantet C., Salvador M., Cambou J. P. Why is hypertension so frequently uncontrolled in secondary prevention?. J Hypertens 2003; 21: 1199–1205

- Stockwell D. H., Madhavan S., Cohen H., Gibson G., Alderman M. H. The determinants of hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in an insured population. Am J Public Health 1994; 84: 1725–1727

- de Macendo C. R., Noblat A. C., Noblat L., de Macedo J. M., Lopes A. A. Use of oral antihypertensive medication preceding blood pressure elevation in hospitalized patients. Arq Bras Cardiol 2001; 77: 328–331

- Berlowitz D. R., Ash A. S., Hickey E. C., Friedman R. H., Glickman M., Kader B. Inadequate management of blood pressure in a hypertensive population. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 1957–1963

- Phillips L. S., Branch W. T., Cook C. B., Doyle J. P., El‐Kebbi I. M., Gallina D. L., et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med 2001; 135: 825–834

- Hyman D. J., Pavlik V. N. Self‐reported hypertension treatment practices among primary care physicians. Blood pressure thresholds, drug choices, and the role of guidelines and evidence‐based medicine. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 2281–2286

- Oliveria S. A., Lapuerta P., McCarthy B. D., L'Italien G. J., Berlowitz D. R., Asch S. M. Physician‐related barriers to the effective management of uncontrolled hypertension. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162: 413–420