Abstract

The prevalence of hypertension in type 2 diabetics is high, though there is no published data for Switzerland. This prospective cohort survey determined the frequency of type 2 diabetes mellitus associated with hypertension from medical practitioners in Switzerland, and collected data on the diagnostic and therapeutic work‐up for cardiovascular risk patients. The Swiss Hypertension And Risk Factor Program (SHARP) is a two‐part survey: The first part, I‐SHARP, was a survey among 1040 Swiss physicians to assess what are the target blood pressure (BP) values and preferred treatment for their patients. The second part, SHARP, collected data from 20,956 patients treated on any of 5 consecutive days from 188 participating physicians. In I‐SHARP, target BP⩽135/85 mmHg, as recommended by the Swiss Society of Hypertension, was the goal for 25% of physicians for hypertensives, and for 60% for hypertensive diabetics; values >140/90 mmHg were targeted by 19% for hypertensives, respectively 9% for hypertensive diabetics. In SHARP, 30% of the 20,956 patients enrolled were hypertensive (as defined by the doctors) and 10% were diabetic (67% of whom were also hypertensive). Six per cent of known hypertensive patients and 4% of known hypertensive diabetics did not receive any antihypertensive treatment. Diabetes was not treated pharmacologically in 20% of diabetics. Proteinuria was not screened for in 45% of known hypertensives and in 29% of known hypertensive diabetics. In Switzerland, most physicians set target BP levels higher than recommended in published guidelines. In this country with easy access to medical care, high medical density and few financial constraints, appropriate detection and treatment for cardiovascular risk factors remain highly problematic.

Introduction

Epidemiological surveys conducted in North America and the UK have shown that the prevalence of hypertension in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients, especially in young people, is higher than in the general population. About 40% of patients with type 2 diabetes are also hypertensive by the age of 45 years Citation[1], Citation[2]. Moreover, by the age of 75, the prevalence of both diseases combined is as high as 60% Citation[1], Citation[3], Citation[4]. Diabetes mellitus and hypertension are frequently associated with microalbuminuria, overt proteinuria and dyslipidemia Citation[5]. In hypertensive diabetic patients, microalbuminuria is the strongest independent cardiovascular risk factor Citation[6]. It has been shown that early detection of microalbuminuria and treatment with drugs affecting the renin–angiotensin system can significantly delay the onset and progression of kidney damage Citation[7–10].

In Switzerland, epidemiological reports on the prevalence of hypertension and its association with diabetes are scarce Citation[11–14]. In one prospective cohort study including 356 type 2 diabetes patients, hypertension was diagnosed in 54% of the patients, albuminuria in 53% and dyslipidemia in 47% Citation[15]. However, no data are available on the diagnostic strategy followed by physicians, especially general practitioners, at the time when hypertensive and diabetic patients are first identified.

The objective of the Swiss Hypertension and Risk Factor Program (SHARP) survey was to determine the frequency of type 2 diabetes associated with hypertension seen in private practice, the risk factors for cardiovascular complications, as well as to collect data on the diagnostic work‐up and therapeutic strategies used by general practitioners and internists in this high‐risk subgroup of patients.

Methods

SHARP was carried out in 2001 as a two‐phase program to collect medical data throughout Switzerland. SHARP has been designed as a cross‐sectional study of unselected patients attending primary care settings, recruited from a representative sample of medical practitioners. In step one (I‐SHARP), 1040 physicians from all three main regions (German, French and Italian) of Switzerland in metropolitan and regional areas were randomly selected to yield a representative sample of medical practitioners in respect to the population. This step assessed the practice of medical practitioners only; no data collection on patients was obtained. Step 2 (SHARP) was a prospective registry where a representative group of 188 physicians collected patient data on hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors in all patients attending their practice throughout a 5‐day period.

First part of the survey, the I‐SHARP interview

In this first part of the survey (I‐SHARP), 1040 physicians from all parts of Switzerland, representative of practitioners usually working with hypertensive and diabetic patients, were asked to complete a short written questionnaire. Doctors were asked to provide data on the weekly percentage of their patients suffering from type 2 diabetes and/or hypertension, state the target blood pressure (BP) values for which they aimed, estimate the percentage of patients able to reach the target, and mention their first line of treatment at the time hypertension and/or diabetes was diagnosed. They were also asked if they screened for microalbuminuria/proteinuria and dyslipidemia at the initial work‐up of diabetes and/or hypertension. Proteinuria was defined as positive if dipstick readings were +, ++ or +++. This subjective data was collected and used as a basis for SHARP.

Second part of the survey, the 5‐day observational survey, SHARP

In this second part of the survey, data from all patients treated on any of five consecutive days from 188 participating physicians were gathered. Using a simple data collection form, physicians were asked to specify, for each patient, the presence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, microalbuminuria/proteinuria and dyslipidemia (possible answers “yes”, “no” or “unknown”), to indicate the BP values and whether any treatment was administered. The data collection was based solely on the physicians' assessments, independent of established guidelines for BP, fasting blood sugar, microalbuminuria and plasma cholesterol levels. For example, if the physician considered the patient normotensive and wrote “no hypertension” despite the BP being >140/90 mmHg, the patient was considered normotensive.

Data analysis

Statistical confidence intervals are based on the correct estimation of a central probability; this can be strongly biased by unknowns. In this survey, very large numbers of “unknowns” were recorded for all categories. It is therefore not feasible to determine standard confidence intervals with these data.

Using the BP values provided, hypertension was also analyzed in accordance with the definition adopted by NHANES Citation[16], which defines hypertension as measured BP⩾140/90 mmHg or receiving antihypertensive therapy, irrespective of the doctor's or patient's self‐reported diagnosis. The high number of “unknowns” can be explained by the fact that the patient population consisted of all patients seeking treatment at any of the participating practices (62% of whom were general practitioners) on any of the five consecutive days selected. This included many younger and otherwise healthy patients; indeed, 17% were younger than 30 years and 52% were younger than 55 years of age. For many patients visiting the physician on this particular day, there was no reason to test for hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, or one of the other conditions researched in this survey. On the other hand, the majority of patients at risk due to well‐known risk factors, such as age, smoking, being overweight, or having relevant personal or family history, are normally investigated for these conditions during medical visits, and the condition would therefore be known for them. We may thus conclude that the majority of those patients in our population for whom the status of one of the pathological conditions is unknown are, in fact, negative. We thus have two subgroups, one where the condition is known (partially consisting of patients at risk) and another subgroup where the condition is not known (mostly consisting of patients not at risk). The probability for risk patients being positive is certainly higher than for younger and healthier patients without risk factors. It seems conservative to assume that the percentage of patients with a positive clinical condition in the second subgroup (the “unknowns”) will not be higher than in the first subgroup (those in whom it is known), i.e. the positives in the “unknown” subgroup are in reality between zero and at most the percentage observed in the “known” subgroup. This provides a lower and an upper limit for the “true” value.

The above reasoning is supported by the observation that, for all pathological conditions surveyed, the percentage of “unknowns” is highest for the lowest age category and significantly decreases with increasing age.

Results

A total of 1040 physicians participated in the I‐SHARP survey: 688 were general practitioners (66%) and 352 (34%) were specialist physicians (271 internal medicine, 37 cardiology and 44 other specialties). In SHARP, a total of 188 physicians, of whom 184 had participated in I‐SHARP, collected prospective data from 20,956 patients (11,432 women and 9307 men, 217 unknown; mean age 52±22 years), and seen during a period of 5 consecutive days. SHARP physicians included 116 general practitioners (62%) and 72 specialist physicians (57 internal medicine, eight cardiology and seven other specialties).

I‐SHARP estimated figures

BP targets

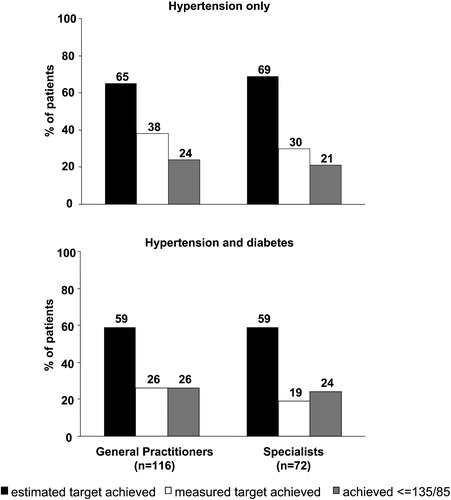

Only 25% of physicians (general practitioners 22%, specialists 31%, p = 0.021) reported that they aimed for target BP values ⩽135/85 mmHg for their hypertensive patients, as recommended by the Swiss Society of Hypertension. Around 19% of physicians aimed for a target BP>140/90 mmHg. In patients with concomitant hypertension and diabetes mellitus, physicians aimed for lower target BP values: 60% strove for ⩽135/85 mmHg, 31% for ⩽140/90 mmHg and 9% for >140/90 mmHg. General practitioners estimated that 65% of their hypertensive patients achieved BP goals, while specialists considered that 69% of their patients were treated on target (Figure ).

Figure 1 Estimate of hypertensive patients (upper panel) and hypertensive diabetics (lower panel) attaining their target blood pressure values as predicted by their doctors in I‐SHARP (solid bars), proportion of hypertensive patients actually achieving measured target goals in SHARP (open bars), and proportion of patients attaining blood pressure values <135/85 mmHg as recommended by the Swiss Society of Hypertension, SSH (gray bars).

Screening for other cardiovascular risk factors

At the initial diagnosis of hypertension, 49% of physicians reported screening for microalbuminuria/proteinuria and 96% for dyslipidemia; for hypertensive diabetic patients, these figures were 87% and 98%, respectively (Table ). There was no difference between general practitioners and specialists in the rate of screening for these conditions.

Table I. I‐SHARP: Physicians testing for risk factors (answers “yes” and “most of the time”).

SHARP achieved figures

The 5‐day observational survey aimed at assessing the concordance between treatment goals and achieved BP results. Among the 20,956 subjects censored in SHARP, 6211 (29.6%) patients were known to be hypertensive, while 11,618 were known to have normal BP. Of the remaining 3127 patients, their doctors declared to be unaware of their BP status. In this latter group, 27.5% of subjects whose BP was measured were found to have values >140/90 mmHg. Moreover, in 10.2% of patients classified by their GP as being normotensive, their BP was found to be >140/90 mmHg on the one reported occasion.

Achieved BP targets

The percentage of hypertensive patients actually achieving individual BP goals defined by their general practitioner was only 38% compared to the estimate of 65% from the I‐SHARP survey (Figure ). When the analysis was performed using target BP values published in guidelines Citation[16], Citation[17] rather than the physician's own target values, this figure dropped to 24% (Figure ). This overestimation was even more marked among specialists, with 69% estimating that they were achieving the target in their patients, but only 31% or 21% of patients with measured BP on target or <135/85 mmHg, respectively (Figure ). In hypertensive patients with diabetes mellitus, this overestimation was even more pronounced (Figure , lower panel). In the latter, angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors were used as their first‐line treatment in 70% of cases, while angiotensin II receptor blockers were the first choice for 28% of diabetic patients.

Other cardiovascular risk factors

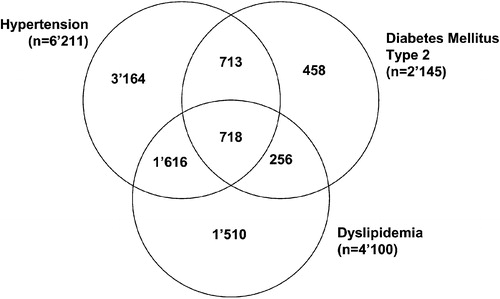

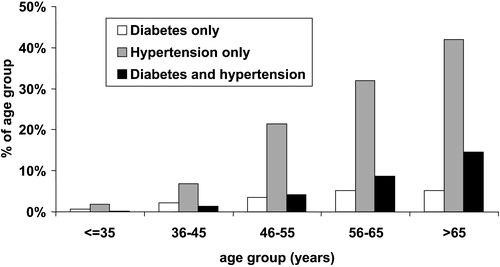

Of the 6211 hypertensive patients, 1431 were also known to suffer from diabetes mellitus (Figure , Table ). The prevalence of hypertension alone or hypertension with diabetes was strongly age‐related, ranging from 21% and 4%, respectively, among the 46–55‐year‐olds, to 42% and 15%, respectively, in patients >65 years of age (Figure ). The prevalence of other risk factors and/or target organ damage as well as treatment for these conditions is reported in Table . Among the 4100 subjects with abnormal serum lipids, 2334 were at the same time hypertensive and 718 were diabetic hypertensives. Almost half the diabetic patients were also dyslipidemic (Figure , Table ).

Figure 2 Distribution of diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia among the 20,956 patients censored in the SHARP cohort.

Figure 3 Prevalence of diabetes mellitus alone (open bars), hypertension alone (gray bars), and diabetes with hypertension (solid bars) in different age groups (entire patient population, n=20,956).

Table II. Prevalence of hypertension, diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors in the SHARP cohort.

Pharmacological treatment

The figures regarding frequency of pharmacological treatment of hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidemia are shown in Table . While only about 6% of hypertensive patients were not on antihypertensive drugs, about 20% of diabetics did not receive oral hypoglycaemic agents or insulin, and only 55% were on lipid‐lowering agents (Table ).

Table III. Prevalence of pharmacological treatment of hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidemia in the SHARP cohort.

From the approximately 50% of hypertensive patients who had a test for microalbuminuria/proteinuria, the number who were positive for microalbuminuria/proteinuria in the entire population was 917, or 4%. In hypertensive diabetics, screening for microalbuminuria/proteinuria was reportedly performed by 86% of I‐SHARP physicians; SHARP results show that 29% of known hypertensive diabetics actually suffer from microalbuminuria/proteinuria. Among these subjects, target BP values were achieved in 31% of hypertensive patients (<140/90 mmHg) and in only 21% of diabetic hypertensives (<135/85 mmHg) (data not shown).

Discussion

The results presented herein are based on the subjective assessment of individual physicians from various specialties evaluating their strategy in the management of hypertension with or without diabetes. These figures also provide a rather rough estimate of the overall incidence of type 2 diabetes and hypertension in Switzerland. However, because the underlying data are subjected to the physician's personal bias, i.e. physicians may have considered a patient normotensive despite the measured BP being as high as 150 mmHg, this may lead to an overestimation of the percentage of patients controlled for hypertension.

Also, the analysis was not based on a representative sample, as data was collected from a cohort of patients attending a GP surgery, rather than using a postcode‐defined population. Despite these limitations, the SHARP survey, which included 20,956 patients from all parts of Switzerland, provides unsettling results for Swiss physicians. They show that roughly one‐third of patients presenting at a medical office are hypertensive, and that one out of four of these patients is also affected by type 2 diabetes mellitus. Both conditions strongly correlated with the patient's age. The prevalence of both diseases combined ranges between 7% and 9% of the entire patient population studied, a figure somewhat lower than in the UK and the USA Citation[1], Citation[2]. It is also interesting to note that approximately a quarter of patients whose doctor did not know their hypertension status had actually BP>140/90 mmHg. Even if repeated high measurements are required to confirm hypertension, this figure suggests a high rate of undiagnosed hypertensive patients. From I‐SHARP, we see that physicians tend to overestimate the percentage of their patients attaining the target BP by a factor of two in the case of hypertensive patients, and three in the case of patients with hypertension and diabetes combined. Even though the quality of medical care in Switzerland is considered high, only 25% of physicians adopt the target BP of 135/85 mmHg in non‐diabetic hypertensive patients, as recommended by the European and Swiss Societies of Hypertension Citation[17], Citation[18]. Even more disconcerting is the observation that 19% of physicians aim for BP values above 140/90 mmHg in the same patients' group. Despite the fact that hypertension is an established cardiovascular risk factor and lowering the BP is effective in reducing cardiovascular morbidity–mortality, more than 6% of patients were not on drug treatment after hypertension has been diagnosed. Overall, the target BP value (mean 139/86 mmHg), as defined by the SHARP physicians, is reached in only 36% of the hypertensive population, a result comparable to what is observed in other countries experiencing difficulties in following the guidelines Citation[2], Citation[19]. Epidemiological data on hypertension for Switzerland are scarce Citation[11–14]. An earlier paper from Buhler et al. in 1994 showed that 19% of known hypertensive patients were not treated at all and 14% were inadequately treated (i.e. diastolic BP>95 mmHg) Citation[20]. SHARP results from 2001 show an improvement with only 6–8% not receiving treatment.

The presence of proteinuria, an early marker of kidney damage, was investigated in hypertensive patients by only half of the attending physicians although this test has been shown to be cost‐effective and allowing identification of a very high‐risk subpopulation Citation[6], Citation[10]. It is well known that proteinuria is a hallmark of kidney damage in diabetic patients, and that pharmacological intervention with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers dramatically improves proteinuria and delays onset and progression of diabetic nephropathy Citation[9], Citation[10], Citation[21], Citation[22]. Based on physicians' self‐assessment (I‐SHARP), 13% of the doctors do not screen their hypertensive diabetic patients for proteinuria. However, according to SHARP, in practice 29% of the physicians did not screen their hypertensive diabetic patients for proteinuria and 26% of the patients with microalbuminuria/proteinuria received no anti‐hypertensive treatment. When proteinuria was detected, the BP was controlled in only 31% of non‐diabetic hypertensive patients and in only 21% of hypertensive diabetics.

Dyslipidemia is better identified as a cardiovascular risk factor, and consequently more often assessed. However, 45% patients with known dyslipidemia did not receive any lipid‐lowering agents. This relatively low rate of pharmacological treatment of dylipidemia may be due to different threshold for the definition of hypercholesterolemia and the threshold for dietary and drug treatment of lipid disorders. It may also indicate that lifestyle changes are sufficient for the management of at least mild cases of dyslipidemia. Similarly, the 20% rate of diabetic patients treated with diet in the SHARP survey is consistent with other community‐based cohorts Citation[23].

In conclusion, our data show that the detection and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in Switzerland remains highly problematic, although there are few financial constraints. A stricter interpretation of the actual BP values is needed. Screening for microalbuminuria/proteinuria in the hypertensive, and particularly in the diabetic population, must be considerably improved and the guidelines for patient management must be better explained and applied. Efforts must be targeted at a more integrated approach based on global risk stratification and better identifying high‐risk subgroups of patients who might benefit strongly from medical intervention.

Acknowledgments

APB is a recipient of the Marie Heim‐Voegtlin Grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation, and received clinical research grants from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Switzerland, and Sanofi‐Synthélabo, Switzerland. Our special thanks go to the 1040 physicians who participated in I‐SHARP and the 188 physicians who participated in SHARP. Their invaluable contributions made this survey possible.

References

- Hypertension in Diabetes Study Group. HDS 1: Prevalence of hypertension in newly presenting type 2 diabetic patients and the association with risk factors for cardiovascular and diabetic complications. J Hypertens. 1993;11. 309–317

- Burt B. L., Whelton P., Roccella E. J., Brown C., Cutler J. A., Higgins M., et al. Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population. Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991. Hypertension 1995; 25: 305–313

- Prescott‐Clarke P., Primatesta P (editors). Health survey for England. 1995. HMSO, London 1997

- Harris M. I., Cowie C. C., Stern M. P (editors). Diabetes in America. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, , Washington, DC 1995, 2nd ed

- Keane W. F., Eknoyan G. Proteinuria, albuminuria, risk, assessment, detection, elimination (PARADE): A position paper of the National Kidney Foundation. Am J Kidney Dis 1999; 33: 1004–1010

- Groop L., Ekstrand A., Forsblom C., Widen E., Groop P. H., Teppo A. M., Eriksson J. Insulin resistance, hypertension and microalbuminuria in patients with type 2 (non‐insulin‐dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1993; 36: 642–647

- Lebovitz H. E., Wiegmann T. B., Cnaan A., Shahinfar S., Sica D. A., Broadstone V., et al. Renal protective effects of enalapril in hypertensive NIDDM: Role of baseline albuminuria. Kidney Int Suppl 1994; 45: S150–155

- Chan J. C., Ko G. T., Leung D. H., Cheung R. C., Cheung M. Y., So W. Y., et al. Long‐term effects of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibition and metabolic control in hypertensive type 2 diabetic patients. Kidney Int 2000; 57: 590–600

- Parving H. H., Lehnert H., Brochner‐Mortensen J., Gomis R., Andersen S., Arner P. Irbesartan in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Microalbuminuria Study Group. The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 870–878

- Lewis E. J., Hunsicker L. G., Clarke W. R., Berl T., Pohl M. A., Lewis J. B., et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin‐receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2001; 345: 851–860

- Rickenbach M., Wietlisbach V., Beretta‐Piccoli C., Moccetti T., Gutzwiller F. [Smoking, blood pressure and body weight in the Swiss population: MONICA study. 1988–89]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr Suppl 1993; 48: 21–28

- Gutzwiller F., Brenner D. Epidemiology of hypertension in old age. Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax 1991; 80: 684–688

- Gutzwiller F., Hoffmann A., Alexander J., Brunner H. R., Schucan C., Vetter W. Epidemiology of blood pressure in 4 Swiss cities. Schweiz Med Wochenschr Suppl 1981; 12: 40–46

- Henzen C., Hodel T., Lehmann B., Mosimann T., Horler U., Joss R. Prevalence and therapy of vascular risk factors in hospitalized type 2 diabetic patients. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 2000; 130: 1979–1983

- Teuscher A., Egger M., Herman J. B. Diabetes and hypertension. Blood pressure in clinical diabetic patients and a control population. Arch Intern Med 1989; 149: 1942–1945

- Burt V. L., Whelton P., Roccella E. J., Brown C., Cutler J. A., Higgins M., et al. Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population. Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991. Hypertension 1995; 25: 305–313

- European Society of Hypertension–European Society of Cardiology Guidelines Committee. 2003 European Society of Hypertension–European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens 2003; 21: 2203–2204

- Conroy R. M., Pyorala K., Fitzgerald A. P., Sans S., Menotti A., De Backer G., et al. SCORE project group. Estimation of the ten‐year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: The SCORE project. Eur Heart J 2003; 24: 987–1003

- Cuspidi C., Michev I., Lonati L., Vaccarella A., Cristofari M., Garavelli G., et al. Compliance to hypertension guidelines in clinical practice: A multicentre pilot study in Italy. J Hum Hypertens 2002; 16: 699–703

- Buhler F. R., de Leche A. S., Schuler G., Gutzwiller F., Baumann F., Schweizer W. [The problem of hypertension in Switzerland. Analysis of a blood pressure study in 21,589 persons]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1976; 106: 99–107

- Lewis E. J., Hunsiker L. G., Bain R. P., Rohde R. D. The effect of angiotensin‐converting‐enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. The Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 1456–1462

- Viberti G., Mogensen C. E., Groop L. C., Pauls J. F. Effect of captopril on progression to clinical proteinuria in patients with insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus and microalbuminuria. European Microalbuminuria Captopril Study Group. JAMA 1994; 271: 275–279

- Bruce D. G., Davis W. A., Cull C. A., Davis T. M. Diabetes education and knowledge in patients with type 2 diabetes from the community: The Fremantle Diabetes Study. J Diabetes Complications 2003; 17: 82–89