Abstract

Background: The association of blood pressure (BP) variability (BPV) in hospitalized patients, which represents day-to-day variability, with mortality has been extensively reported in patients with stroke, but poorly defined for other medical conditions.

Aim and method: To assess the association of day-to-day blood pressure variability in hospitalized patients, 10 BP measurements were obtained in individuals ≥75 years old hospitalized in a geriatric ward. Day-to-day BPV, measured 3 times a day, was calculated in each patient as the coefficient of variation of systolic BP. Patients were stratified by quartiles of coefficient of variation of systolic BP, and 30-day and 1-year mortality data were compared between those in the highest versus the lowest (reference) group.

Results: Overall, 469 patients were included in the final analysis. Mean coefficient of variation of systolic BP was 12.1%. 30-day mortality and 1-year mortality occurred in 29/469 (6.2%) and 95/469 (20.2%) individuals respectively. Patients in the highest quartile of BPV were at a significantly higher risk for 30-day mortality (HR =4.12, CI 1.12–15.10) but not for 1-year mortality compared with the lowest BPV quartile (HR =1.61, CI 0.81–3.23).

Conclusions: Day-to-day BPV is associated with 30-day, but not with 1-year mortality in hospitalized elderly patients.

Introduction

Mean arterial pressure is probably the single most important factor associated with cerebrovascular morbidity and mortality and thus most studies use this value for targeting medical therapy. Yet, blood pressure (BP) variability (BPV), defined as variation in BP levels over a time period, has been found in several studies to be associated with mortality and adverse cardiovascular outcomes [Citation1–4], although other studies failed to find such an association [Citation5].

Systolic BPV has been defined by most studies as the standard deviation of systolic BP and by the coefficient of variation of systolic BP [Citation1].

Long term variability has been extensively reported to be associated with cardiovascular mortality, whereas mid-term (day-to-day or week-to-week) and short-term (beat-to-beat or minute-to-minute) variability are less clearly associated with this outcome [Citation6]. The association of day-to-day BPV in hospitalized patients with mortality has been extensively reported in patients with stroke [Citation7,Citation8], but poorly defined for other medical conditions. Although data is limited, previous studies found an association between home-measured day-to-day BPV and cardiovascular mortality [Citation9,Citation10]. In the elderly, heart rate variability and BPV were suggested as potential clinical markers that may predict negative health outcomes [Citation11]. In this paper we attempt to assess the association between systolic BPV and 30-day and 1-year mortality in a cohort of elderly patients hospitalized in a geriatric ward for a variety of medical conditions.

Methods

Study population

All elderly individuals hospitalized in the Geriatric Ward at the Rabin Medical Center between October 2012 and July 2015 were screened for eligibility to be included in the inter-arm BP study [Citation12]. Our geriatric ward is a 30-bed ward which admits patients ≥75 years of age with various acute medical problems (patients 65–75 years old are infrequently admitted following femoral neck fractures). The exclusion criteria of the inter-arm study were detailed previously [Citation12] and included patients who were expected to survive less than 24 hours from admission, patients with systolic BP lower than 90 mmHg on admission and patients in whom simultaneous BP measurement could not be performed. Since patients with an acute infection as the cause of hospitalization may have different BP levels during hospitalization due the resolution of the infection, all patients with a discharge diagnosis compatible with an acute infection were excluded from the present analysis. In addition, patients who did not have at least 3 additional BP measurements on 3 different days during hospitalization were also excluded. The study was approved by the Ethics committee of the Rabin Medical Center and all patients or their legal guardians gave informed consent.

BP measurement and data collection

The initial BP measurement was performed by a designated technician in a quiet room, in the supine position following at least 5 minutes of rest. BP was measured simultaneously in both arms with a standard sphygmomanometer (Vital Signs Monitor 52 NTP model, Welch Allyn Protocol, Inc, Beaverton, Ore) calibrated according to manufacturer's recommendations. Additional measurements performed during the hospitalization were performed at least once daily in the arm in which the higher BP was recorded on the initial BP measurement. For the purpose of the study, the initial 2 BP measurements were used in addition to at least 3 other measurements to a total of 5–10 BP measurements. The standard deviation of systolic BP and the coefficient of variation of systolic BP were calculated from the first available 10 BP measurement. If the patient was discharged and only 3–7 additional BP measurements were available we included all BP measurements. Medical history and patients' characteristics retrieved from the patients' medical records included age, sex, number of days of hospitalization and comorbidities. In addition, all medications dispensed during hospitalization were recorded and the changes made in anti-hypertensive agents on admission or during hospitalization were recorded. Laboratory parameters evaluated included fasting serum glucose levels, lipid profile and renal functions. Data on mortality were available for all participants from the Ministry of Internal Affairs registry.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis for this paper was generated using SAS Software, Version 9.4. Continuous variables were presented by mean ± std, Categorical variables were presented by (N, %). The coefficient of variation was calculated for the first 10 systolic BP measurements, as stated above. Baseline patient characteristics were calculated by quartiles of coefficient of variation of systolic BP.

The General Linear Model was used to compare the value of continuous baseline variables between the coefficient of variation quartiles and Chi-Square was used to compare the value of categorical baseline variables. Logistic Regression was used to analyze the effect of coefficient of variation on 30-day and 1-year mortality, unadjusted and adjusted for covariates. Our model included adjustment for age, sex, mean systolic BP, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and Katz index of independence in activities of daily living. Two sided p values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

During the study period, 3774 individuals were hospitalized in the geriatric ward of which 557 were recruited to the inter-arm study and were used for the analysis of BPV. Of these, 88 were excluded because they were hospitalized due to an acute infection and the final analysis was performed on 469 patients. The most common reasons for hospitalization were observation following orthopedic surgery (n = 87), recurrent falls (n = 74), stroke (n = 40), other forms of trauma (n = 32) and evaluation before performance of trans-catheter aortic valve replacement (n = 18). The average number of BP measurements was 9.54/person and 387/469 patients had 10 available BP measurements. Baseline characteristics of patients, presented by coefficient of variation of systolic BP quartiles, are presented in . Age, gender, co-morbidities and the length of hospitalization were not significantly different between the four groups.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients presented by coefficient of variation of systolic blood pressure quartiles.

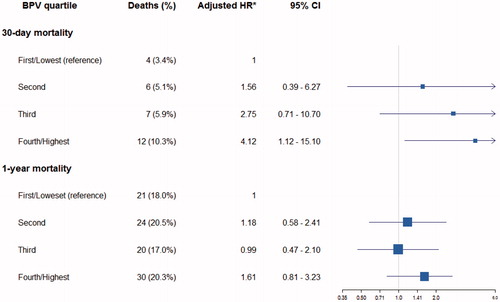

Mortality in the entire cohort was 6.2% (29/469) and 20.2% (95/469) for 30-day and 1-year, respectively. Both the unadjusted and multivariable adjusted (for age, sex, mean systolic BP, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and Katz index of independence in activities of daily living) hazard ratios for 30-day mortality were significantly higher in the fourth BPV quartile compared with the first BPV quartile (Table 2 – provided in the Online Supplement). The adjusted hazard ratios for 30-day and 1-year mortality associated with each quartile of coefficient of variation of systolic BP are presented in . The unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for 30-day mortality in the fourth quartile compared with the first quartile were 3.22 (CI 1.01–10.32) and 4.12 (CI 1.12–15.10), respectively. Unadjusted and multivariable adjusted hazard ratios for 1-year mortality of patients in the fourth BPV quartile were 1.58 (CI 0.84–2.96) and 1.61 (CI 0.81–3.23), respectively. Similar associations were present when the analysis was performed for the standard deviation from mean systolic BP instead of the coefficient of variation of systolic BP. Diabetes did not significantly influence the association between BPV and mortality; 30-day mortality in diabetic patients was 7.6% (12/157) compared with 6.2% for the entire cohort. Overall, anti-hypertensive agents were either added or omitted from the medical treatment prescribed prior to hospitalization in 105 (22.5% of the entire cohort) patients, whereas in 362 patients anti-hypertensive agents were not changed. Patients for whom anti-hypertensive agents were changed during hospitalization distributed almost equally across the first (4.2%), second (6.4%), third (6.4%) and fourth (5.3%) study BPV quartiles (p = .38).

Figure 1. Forest plot of adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for all cause mortality associated with quartile of coefficient of variation of systolic blood pressure. *adjusted for age, sex, mean systolic BP, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and Katz index of independence in activities of daily living.

Discussion

This study is the first to report an increased 30-day mortality rate in elderly patients with high BPV compared with patients with low BPV. By dividing our study population into two groups (with a median BPV of 15.41 mmHg), high BPV predicted 30-day mortality but not 1-year mortality in a statistically significant manner (data not shown). In order to create more homogenous groups, study population was divided into quartiles of BPV, comparing those in highest versus lowest (reference) group. The fourth quartile of BPV was associated with an adjusted 30-day mortality hazard ratio of 4.12 (p = .03) compared with the reference group, and an association between BPV quartile (across all four quartiles) and 30-day mortality was demonstrated (p = .18). BPV has been reported to be associated with stroke [Citation7] and cognitive decline [Citation13] as well as with cardiovascular outcomes in the elderly. Eto and colleagues reported that a high variability based on 24-hour BP monitoring was associated with increased cardiovascular mortality [Citation14], whereas Chowdery reported that between-visit BPV was associated with a risk for myocardial infarction, stroke and congestive heart failure [Citation15].

Although BPV during hospitalization is easily appreciated and does not require recurrent outpatient visits, its clinical implication may be limited due to the fact that it may represent the mere response to treatment of the condition of the patient. In this regard, patients with admission BP <90 mmHg, patients who were hospitalized due to an acute infection and patients who were expected to die within 24 hours from admission were excluded from the study, which should have minimized the contribution of treatment to BPV. In addition we evaluated all changes made in anti-hypertensive medications during hospitalization in the study cohort and found that there was no significant difference in the distribution of BPV between patients in which changes were made and those in which anti-hypertensive treatment was unchanged.

Diabetes mellitus has been reported to be associated with increased BPV. This has been attributed to both increased plasma glucose levels as well as to autonomic dysfunction and to increased arterial stiffness [Citation16,Citation17]. In this cohort, diabetes was not more prevalent in patients with a high BPV and the association with mortality was similar in diabetics and non-diabetics. It is possible that in elderly individuals, the factors associated with increased BPV (increased arterial stiffness and autonomic dysfunction) are so prevalent irrespective of the presence of diabetes mellitus.

This study supports the claim that high day-to-day BPV is a consequence of autonomic dysregulation, and a marker for disorders that impair autonomic regulation, causing loss of adaptive capacity and frailty that predicts health outcomes and mortality in the elderly population [Citation11]. The fact that 1-year mortality was not significantly increased in patients with a high BPV compared with patients with a low BPV is probably the result of the very high mortality rate in the study population which included hospitalized elderly patients. In this population, the prevalence of co-morbidities affecting mortality is so high that the influence of factors such as BPV is negligible.

This study has several limitations. First, although patients were followed-up prospectively, the cohort was initially recruited for the inter-arm study. Second, despite the fact that we attempted to exclude patients in whom the medical treatment given during hospitalization influenced BPV, the fact that we included patients hospitalized with pain following falls of fractures may have resulted in BPV being influenced by the treatment, frequently including drugs that are not antihypertensives that may affect the BP (i.e. opioids, neuroleptics). Because our geriatric medical ward care for orthopedic patients and patients selected for cardiac intervention, and manage both chronic disorders and acute exacerbations, some of the patients were treated with polypharmacy, a possible confounder. Despite these limitations, this is the largest in-hospital series performed not exclusively in hospitalized stroke patients in which the important association between BPV and mortality was evaluated. Third, cause-specific mortality analysis was not performed and thus it cannot be concluded whether mortality was due to cardiovascular causes as may be expected in patients with high BPV. Yet, the fact that all-cause mortality at 30 days was significantly higher in patients with high BPV compared with low BPV has clinical significance as BPV may be easily evaluated in hospitalized patients and may serve as a readily available tool for risk assessment in elderly patients.

Conclusions

High BPV is associated with increased 30-day mortality in hospitalized elderly patients and may help in identifying elderly patients at high risk for short term mortality during hospitalization irrespective of mean BP.

Supplemental_content.docx

Download MS Word (17.2 KB)Disclosure statement

All authors had access to the data and a role in the writing of the manuscript.

References

- Muntner P, Shimbo D, Tonelli M, et al. The relationship between visit-to-visit variability in systolic blood pressure and all-cause mortality in the general population: findings from NHANES III, 1988 to 1994. Hypertension. 2011;57:160–166.

- Rothwell PM. Limitations of the usual blood-pressure hypothesis and importance of variability, instability, and episodic hypertension. Lancet. 2010;375:938–948.

- Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E, et al. ASCOT-BPLA and MRC Trial Investigators. Effects of β blockers and calcium-channel blockers on within-individual variability in blood pressure and risk of stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:469–480.

- Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E, et al. Prognostic significance of visit-to-visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension. Lancet. 2010;375:895–905.

- Tziomalos K, Giampatzis V, Bouziana SD, et al. No association observed between blood pressure variability during the acute phase of ischemic stroke and in-hospital outcomes. AJHYPE. 2016;29:841–846.

- Stevens SL, Wood S, Koshiaris C, et al. Blood pressure variability and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;354:i4098.

- Fukuda K, Kai H, Kamouchi M, et al. FSR Investigators; steering committee of the Fukuoka Stroke Registry included. day-by-day blood pressure variability and functional outcome after acute ischemic stroke: Fukuoka Stroke Registry. Stroke. 2015;46:1832–1839.

- Buratti L, Cagnetti C, Balucani C, et al. Blood pressure variability and stroke outcome in patients with internal carotid artery occlusion. J Neurol Sci. 2014;339:164–168.

- Kikuya M, Ohkubo T, Metoki H, et al. Day-by-day variability of blood pressure and heart rate at home as a novel predictor of prognosis: the Ohasama study. Hypertension. 2008;52:1045–1050.

- Johansson JK, Niiranen TJ, Puukka PJ, et al. Prognostic value of the variability in home-measured blood pressure and heart rate: the Finn-Home Study. Hypertension. 2012;59:212–218.

- Lipsitz LA. Dynamics of stability: the physiologic basis of functional health and frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:B115–B125.

- Weiss A, Grossman A, Beloosesky Y, et al. Inter-arm blood pressure difference in hospitalized elderly patients is not associated with excess mortality. J Clin Hypertens. 2015;17:786–791.

- Qin B, Viera AJ, Muntner P, et al. Visit-to-visit variability in blood pressure is related to late-life cognitive decline. Hypertension. 2016;68:106–113.

- Eto M, Toba K, Akishita M, et al. Impact of blood pressure variability on cardiovascular events in elderly patients with hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2005;28:1–7.

- Chowdhury EK, Owen A, Krum H, et al. Second Australian National Blood Pressure Study Management Committee. Systolic blood pressure variability is an important predictor of cardiovascular outcomes in elderly hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2014;32:525–533.

- Ruiz J, Monbaron D, Parati G, et al. Diabetic neuropathy is a more important determinant of baroreflex sensitivity than carotid elasticity in type 2 diabetes. Hypertension. 2005;46:162–167.

- Frattola A, Parati G, Gamba P, et al. Time and frequency domain estimates of spontaneous baroreflex sensitivity provide early detection of autonomic dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1997;40:1470–1475.