Abstract

Background: Data are sparse regarding ambulatory blood pressure (BP) reduction of up-titration from a standard dose to a high dose in both nifedipine controlled-release (CR) and amlodipine. This was a prospective, randomized, multicenter, open-label trial.

Patients and methods: Fifty-one uncontrolled hypertensives medicated by two or more antihypertensive drugs including a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor and a calcium antagonist were randomly assigned to either the nifedipine CR (80 mg)/candesartan (8 mg) group or the amlodipine (10 mg)/candesartan (8 mg) group.

Results: The changes in 24-hr BP were comparable between the groups. The nifedipine group demonstrated a significant decrease in their urinary albumin creatinine ratio, whereas the amlodipine group demonstrated a significant decrease in their NTproBNP level. However, there was no significant difference in any biomarkers between the two groups.

Conclusion: Nifedipine showed an almost equal effect on ambulatory blood pressure as amlodipine. Their potentially differential effects on renal protection and NTproBNP should be tested in larger samples.

Introduction

Strict blood pressure (BP) control provides a regression of target organ damage, which leads to a favorable impact on the individual's cardiovascular outcome [Citation1]. Despite this, the rate of optimal BP control remains poor. To achieve strict BP control, most patients require a combination of at least two antihypertensive drugs [Citation2,Citation3]. Various guidelines recommend a combination of a calcium channel blocker (CCB) and a renin angiotensin system inhibitor (RASI) to achieve optimal BP control [Citation4,Citation5].

Nifedipine controlled-release (CR) and amlodipine are the most widely used CCBs in clinical practice. Up-titration from a standard dose to a high dose of both nifedipine CR and amlodipine has been shown to lower BP more extensively than a standard-dose, respectively. In Japanese untreated hypertensive patients, up-titration from the standard dose (5 mg per day) to a high dose of amlodipine (10 mg per day) incrementally reduced clinic and home BP from the baseline [Citation6]. In Japanese hypertensive patients with uncontrolled BP despite their treatment with standard-dose nifedipine (40 mg per day) in combination with other antihypertensive drugs, the up-titration of nifedipine CR to 80 mg per day provided an effective reduction in clinic BP [Citation7].

Although RASIs have an apparent renoprotective effect [Citation8], it was reported that the combination of low-dose nifedipine CR with candesartan significantly reduced BP and urinary albumin excretion compared to up-titrated candesartan monotherapy [Citation9]. Among four CCBs (nifedipine, amlodipine, cilnidipine, and efonidipine), only nifedipine and cilnidipine monotherapy provided a significant reduction in urinary albumin excretion despite the similar BP reductions provided [Citation10]. Therefore, nifedipine, itself may have renoprotective effect beyond the effect of BP reduction. Few studies have investigated whether there is a difference in the BP reduction and renal protection provided by high-dose nifedipine CR (80 mg) and that provided by high-dose amlodipine (10 mg) — which are the highest doses permitted in Japan — in uncontrolled hypertensive patients medicated by two or more drugs. If a differential class effect of high-dose CCBs for ambulatory BP control and renal protection in uncontrolled hypertension is observed, a new strategy could be devised for the management of hypertension.

We conducted the present study to compare the BP-lowering effects on ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) and the change in biomarkers including urinary albumin excretion provided by high-dose nifedipine CR (80 mg per day) versus high-dose amlodipine (10 mg per day) in combination with candesartan (8 mg per day) in uncontrolled hypertensive patients medicated by two or more antihypertensive drugs.

Patients and methods

Study design

This was a multicenter, randomized, open-label, active-controlled, two treatment arm clinical trial investigating the effects of nifedipine CR 80 mg/candesartan 8 mg (nifedipine CR group) and amlodipine 10 mg/candesartan 8 mg combination therapy (amlodipine group) on BP assessed by ABPM and surrogate biomarkers in uncontrolled hypertensive patients. The trial was named the Calcium Antagonist Controlled-Release High-Dose Therapy in Uncontrolled Refractory Hypertensive Patients (CARILLON) study. The study was conducted in accord with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of the participating study sites. This study was registered at the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000011161), and written informed consent was obtained from all of the patients.

We established an independent CARILLON study control center at Sogo Rinsho Médéfi Co. for the study’s administration and data management. Statistical analyses were performed by the independent Global Analysis Research Center of BP at the Jichi Medical University COE Cardiovascular Research and Development Center (JCARD).

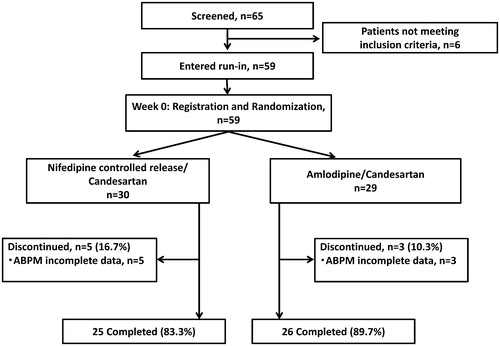

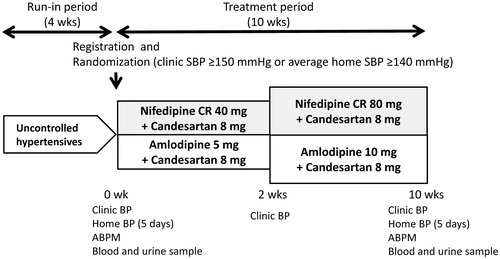

shows the study design. At the end of the 4-wk run-in period with dual antihypertensive therapy or triple therapy with the usual dose of a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor (i.e. Angiotensin Receptor Blocker [ARB], Angiotensin-converting-enzyme Inhibitor [ACEI], or Direct Renin Inhibitor [DRI]) and a CCB that is usually recommended in Japan, 59 eligible patients were registered and were randomized to either the nifedipine CR (NCR) group or the amlodipine (AML) group. At the end of 2 wks of treatment, the nifedipine CR was forced-titrated to 80 mg per day and the amlodipine was forced-titrated to 10 mg per day. Physicians were not permitted to change any antihypertensive medications other than nifedipine CR and amlodipine throughout the treatment period. Other drugs that had the potential to interfere with the safety and efficacy of the study drugs were also not allowed. At the baseline and at the end of the study, each patient's ambulatory BP, home BP, clinic BP, and blood and urine parameters were measured. Home BP was measured for five consecutive days just before the initial randomization and at the end of the study.

Figure 1. Study design. Uncontrolled hypertensive patients who were treated with two or more antihypertensive drugs with the usual dose of a renin-angiotensin system inhibitor and a calcium channel blocker were registered in this study. Abbreviations: SBP, systolic blood pressure; ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring.

Patients

The patients were recruited from multiple outpatient centers in Japan. The entry period was from August 2013 to July 2015. All subjects were Japanese essential hypertensive patients who, at baseline, were being treated with the usual dose of a CCB (i.e. amlodipine 5 mg, nifedipine CR 40 mg, azelnidipine 8 mg, cilnidipine 10 mg, benidipine 4 mg or nicardipine LA 40 mg) plus the usual dose of an ACEI, ARB, or DRI: i.e. imidapril 5 mg, candesartan 8 mg, azilsartan 20mg, valsartan 80 mg, irbesartan 100 mg, telmisartan 40 mg, olmesartan 20 mg, losartan 50 mg, or aliskiren 150 mg. During the 4-wk run-in period, all patients continued each medication. Patients with a clinic systolic BP (SBP) ≥150 mmHg or average home SBP for 5 days ≥140 mmHg were eligible for this study.

Patients were excluded if they had secondary hypertension, cardiogenic shock, atrial fibrillation, severe hepatic or renal dysfunction, hemodialysis, a recent history (≤6 months) of myocardial infarction or stroke, or allergy to drugs used in this study. Women who were pregnant or could become pregnant were also excluded.

Blood pressure measurement

Brachial BP at the clinic was recorded as the average of two measurements taken at a 15-sec interval using a validated oscillometric device (HEM-7080IT, Omron Healthcare, Lake Forest, IL, USA) at each visit after an initial 5 min of seated rest. ABPM was carried out with an automatic ABPM device (TM2431, A&D Co., Tokyo), which recorded BP and pulse rate (PR) every 30 min for 26 hr by the oscillometric method. ABPM was performed at baseline and at the end of the study. Using the same device used for the clinic BP measurement, home BP was measured on five consecutive days during the last week of the run-in period prior to the study allocation, and during the last week of the treatment period, four times daily (twice each at wake-up time and bedtime). Home BP was calculated as the average of morning or evening BP values for five consecutive days.

We defined '24-hr BP' as the average of all BP readings throughout a given 24-hr period. 'Nighttime BP' was defined as the average of BP from the time when the patient went to bed until the time the patient got out of bed, and 'daytime BP' was defined as the average of BP values during the rest of the day. 'Early-morning BP' was defined as the average BP during the first 2 hr after waking (four BP readings). The 'lowest nighttime BP' was defined as the average BP of three readings centered on the lowest nighttime reading. The 'morning BP surge' was calculated as the early-morning BP minus the lowest nighttime BP.

Biomarker assays

Blood and spot urine samples for laboratory evaluations (hematology, blood chemistry, and urine measurements) were obtained from the patients in the morning in a fasting state at baseline and at the end of the study. The blood samples were centrifuged at 3,000g for 15-min at room temperature. Plasma/serum and urine samples were stored at 4 °C in refrigerated containers and sent to a commercial laboratory (SRL Inc., Tokyo) within 24 hr of collection. Serum creatinine, the urinary albumin creatinine ratio (UACR), N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide (NTproBNP), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-TnT) were assayed within 24 hr of the sample collection at SRL.

Study outcome

The primary outcome was the change in average 24-hr SBP values. The secondary outcomes were as follows: changes in average 24-hr DBP, daytime BP, nighttime BP, morning BP surge, average home BP, UACR, NTproBNP, hsCRP, and hs-TnT.

Statistical analyses

The sample size was calculated based on the assumption that the nifedipine CR group would demonstrate superiority to the amlodipine group with respect to the mean 24-h blood-pressure-lowering effect by 9 ± 10 mm Hg [Citation11], with a statistical power of 80%. The actual sample size specified in the protocol was 20 subjects per group, 40 in total, which had a 80% statistical power for mean 24-hr SBP reduction, using a two-sided test at an α level of 0.05. Assuming 10% drop-out, the needed sample size was 46. Thus, the 59 patients enrolled in our study were sufficient to elucidate the difference in mean 24-hr SBP between the two groups.

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS ver. 23 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The normality of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test before analysis. Statistical analyses were performed based on an intention-to-treat principal. Data are expressed as the means (± standard deviation [SD]) or percentages. Differences between the groups were analyzed with the unpaired Student’s t-test for normally distributed variables. Categorical parameters were compared with the Chi-square test. UACR, NTproBNP, hsCRP, and hsTnT were log transformed because these variables were not normally distributed, and the results are expressed as geometric mean values with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A two-tailed paired t-test was used to compare the mean values between baseline and after treatment for each treatment group. Interactions between treatment groups according to the baseline BP level and the change in BP levels were evaluated by a multiple linear regression model. Two-sided values of p < .05 were considered to indicate significance.

Results

Fifty-nine patients were randomized and allocated to the candesartan/nifedipine CR 80 mg group (NCR, n = 30) or candesartan/amlodipine 10 mg group (AML, n = 29). Because of the incomplete data of ABPM, 5 and 3 patients were excluded from the nifedipine CR and amlodipine groups, respectively (). We analyzed 51 patients (NCR, n = 25; AML, n = 26) who completed the treatment period. The patients’ average age was 67.9 ± 12.4 years, and the prevalence of males was 63.1%. The patients' average BMI was 27.1 ± 4.6 kg/m2. The prevalence of diabetes and the history of myocardial infarction and stroke were 37.3%, 3.9%, and 3.9%, respectively. The number of patients medicated by two antihypertensive drugs was 35 (68.6%), and that of the patients medicated with more than three antihypertensive drugs was 16 (31.4%). presents the baseline characteristics of the patients in the NCR and AML groups. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between two groups.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of Japanese uncontrolled hypertensive patients (n = 51) medicated by two or more antihypertensive drugs.

Blood pressure parameters

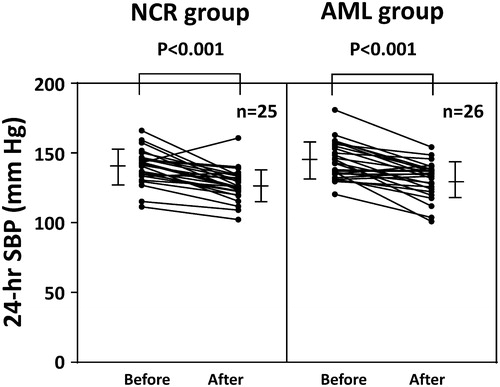

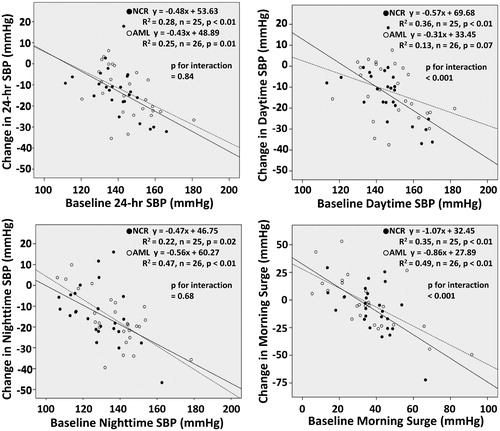

Both treatment groups demonstrated significant reductions in 24-hr SBP and DBP, daytime SBP and DBP, nighttime SBP and DBP, early morning SBP and DBP, and lowest nighttime SBP at the end of the study (, ). However, there were no significant difference in these ambulatory BP parameters between the two treatment groups. The change in the morning BP surge from baseline to the end of the study was −8.0 ± 21.8 mmHg in the nifedipine group, but this was not a significant reduction (p = .08). The amlodipine group showed no significant reduction in morning BP surge (−2.0 ± 24.2 mmHg, p = .67). The interactions between treatment groups concerning (a) the baseline daytime SBP level and the change in daytime SBP, and (b) the baseline morning BP surge level and the change in morning BP surge were significant, respectively ().

Figure 3. Mean 24-hr SBP before and after treatment. Each patient’s mean 24-hr SBP before and after ten weeks of treatment. The central bar on the vertical bars represents the mean ± SD. NCR: nifedipine controlled-release; AML: amlodipine; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

Figure 4. Scatter plot of the linear relationship between the baseline blood pressure (BP) level and the change in BP and the interaction between treatment drugs concerning the baseline BP level and the change in BP. NCR: nifedipine controlled-release group; AML: amlodipine group.

Table 2. Changes in blood pressure.

At the end of two weeks, just before the forced titration of CCBs, there was no significant difference in clinic BP between the treatment groups (). Concerning clinic and home BP, both the NCR and AML treatment groups demonstrated a significant reduction in clinic SBP and DBP and home SBP and DBP. However, there was no significant difference in these clinic and home BP parameters between the treatment groups ().

Biomarkers

provides the biomarker data at baseline and follow-up. The nifedipine CR group demonstrated a significant decrease in UACR at the end of the study, whereas there was no significant difference in the amlodipine group. Amlodipine therapy significantly decreased the serum NTproBNP level, whereas the nifedipine therapy showed no significant reduction in NTproBNP. There was no significant difference in any biomarkers between the nifedipine and amlodipine groups.

Table 3. Biomarker results in the NCR and AML treatment groups.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated that both high-dose nifedipine CR and high-dose amlodipine in combination with candesartan significantly reduced ABPM parameters, but there was no significant difference in the ambulatory BP-lowering effect between the two treatments. The nifedipine CR/candesartan therapy tended to reduce the morning BP surge from baseline to the end of the study, but this was not a significant reduction. The interactions between treatment groups concerning (a) the baseline daytime SBP level and the change in daytime SBP, and (b) the baseline morning BP surge level and the change in morning BP surge were significant, respectively.

Concerning the change in biomarkers, the NCR group demonstrated a significant decrease in UACR, and the AML group demonstrated a significant decrease in NTproBNP, whereas there was no significant difference in any biomarkers between the two groups.

Change in BP between the two treatment groups

Our findings revealed that both high-dose nifedipine CR and high-dose amlodipine in combination with a fixed dose of candesartan significantly reduced ambulatory SBP levels by 10 mmHg or more in treated hypertensive patients who had failed to achieve BP goals with two or more antihypertensive drugs treatment that included a RASI and a CCB. Our previous study showed that high-dose amlodipine (10 mg per day) had the same extent of 24-hr BP reduction compared with the combination of losartan 50 mg with hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg in untreated hypertensive patients [Citation12]. Concerning the effect of high-dose nifedipine CR for BP reduction, there have been several single-arm studies. Kobayashi et al. reported that switching from another antihypertensive drug to high-dose nifedipine CR (80 mg per day) or up-titration from standard-dose nifedipine CR (40 mg per day) to high-dose nifedipine CR was effective for clinic BP reduction [Citation13]. Another group reported that in patients with uncontrolled BP treated with standard-dose nifedipine CR (40 mg per day) in combination with other antihypertensive drugs, up-titration to high-dose nifedipine CR (80 mg per day) significantly reduced clinic BP [Citation7]. Our present findings and the results of these previous studies suggest that up-titration from the standard dose of both nifedipine CR and amlodipine is effective for BP reduction in uncontrolled hypertensives.

In our nifedipine CR group, the morning BP surge tended to be reduced, and the interaction between treatment groups concerning the baseline morning BP surge level and the change in morning BP surge was significant. In addition, the same association was significant in daytime SBP. One of the reasons for this may be the difference in the timing of drug administration (nifedipine CR twice daily and amlodipine once daily). Long-acting antihypertensive drugs have recently been used and are preferable in clinical practice because they can improve a patient's compliance with the drug regimen and suppress BP variability [Citation14]. The administration of an antihypertensive drug twice daily may be effective to reduce the targeting period's uncontrolled BP in hypertensive patients medicated with multiple antihypertensive drugs.

Our analysis showed that there was no significant difference in clinic, home and ambulatory BP reduction between the nifedipine CR and amlodipine groups. There are few data concerning direct comparisons of BP-lowering effects between nifedipine CR and amlodipine. Kuga et al. reported that in untreated hypertensive patients, the reduction in 24-hr SBP/DBP was significantly greater in patients treated with the standard dose of nifedipine CR, i.e. 40 mg per day (−22 ± 6/−13 ± 8 mmHg) compared to patients treated with the standard dose of amlodipine, i.e. 5 mg per day (−13 ± 13/−11 ± 9 mmHg) [Citation11]. However, the patients in that study were not definitely randomized, and the 24-hr BP levels at both baseline and during the treatment period were significantly higher in the nifedipine CR group than in the amlodipine group.

Comparisons of BP reduction between nifedipine CR and amlodipine in combinations with a fixed dose of ARB have been reported. The ADVANCE-combi study was performed to compare the combination therapy of nifedipine CR + valsartan versus that of amlodipine + valsartan, which were titrated for target clinic BP in untreated hypertensive patients [Citation15]. That study demonstrated that the standard dose (40 mg per day) of nifedipine CR-based combination resulted in a higher target clinic BP achievement rate than the standard dose (5 mg per day) of amlodipine-based combination in both treated and untreated essential hypertensive patients [Citation15]. The different characteristics of the patients under study might explain this diversity. Our study enrolled only uncontrolled hypertensive patients medicated with two or more antihypertensive agents, and we treated them with the highest dose (permitted in Japan) of nifedipine or amlodipine. Our findings suggest that using the highest dose of nifedipine CR or amlodipine is a good choice for controlling BP throughout the 24-hr in patients with uncontrolled BP treated with two or more antihypertensive agents.

Change in biomarkers between the NCR and AML groups

There was no significant difference in the biomarkers UACR, NTproBNP, HsCRP, or Hs-TnT between the candesartan/nifedipine CR 80 mg (NCR) group and the candesartan/amlodipine 10 mg (AML) group. Interestingly, in the NCR group, the UACR at the end of the study was significantly decreased compared to the baseline, but this association was not found in the AML group. This finding is accord with previous reports. In a comparison of four types of CCB monotherapy (nifedipine, amlodipine, cilnidipine, and efonidipine), nifedipine and cilnidipine provided a significant reduction in the UACR regardless of BP reduction [Citation10].

The reason why nifedipine has been superior for a reduction in the UACR compared to amlodipine is unclear. In another study, advanced glycation end products (AGEs, which are proteins or lipids that become glycated after exposure to sugars) had a pro-inflammatory action under diabetes and non-diabetes [Citation16]. Moreover, the interaction between the receptor for AGE (RAGE) and its ligands enhanced oxidative stress and inflammatory response [Citation16]. Nifedipine, but not amlodipine, down-regulated RAGE mRNA levels and was subsequently shown to reduce reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in vitro [Citation17]. Suppressing RAGE expression by nifedipine could have an anti-inflammatory effect on endothelial cells, which may lead to the reduction in the UACR.

In the present amlodipine group, NTproBNP, one of the natriuretic peptides, was significantly decreased at the end of the study compared to the baseline, in accord with previous investigations. We reported that high-dose amlodipine treatment could provide a reduction in BNP levels [Citation6,Citation12]. These interpretations might be an overstatement of our results, because there were no significant differences in the change of the UACR or NTproBNP between our two treatment groups, and the study's sample size was relatively small.

In general populations, both Hs-CRP and Hs-TnT correlate with cardiovascular prognosis [Citation18–20]. However, it has been unclear whether both of these biomarkers are modifiable factors that could be used to confirm the effect of interventions. In this study, there were no significant changes in Hs-CRP or Hs-TnT between the two different antihypertensive drugs used. Further studies are needed to investigate whether these biomarkers are modifiable, in another intervention or a large sample-sized study.

Conclusion

In uncontrolled hypertensives, both high-dose nifedipine CR (80 mg/day) and high-dose amlodipine (10 mg/day) in combination with candesartan (8 mg/day) showed a BP-lowering effect on 24-hr ambulatory BP. However, there was no class effect of BP-lowering between these two drugs. To control specific periods' BP, especially the morning BP surge, twice-daily high-dose nifedipine CR might be superior to high-dose amlodipine. In addition, the potentially differential effects of these drug combinations on renal protection and NTproBNP should be tested in the larger samples.

Organization and management

The CARILLON Society, based at the medical offices of the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Jichi Medical University School of Medicine, played a central role in carrying out the study. The study protocol, which had been approved by the CARILLON Society, was reviewed by the Jichi Medical University Institutional Review Board (IRB) for its scientific and ethical properties, conflicts of interest, etc., and was granted approval. To ensure the transparency of the study, activities related to the study secretariat, data management and monitoring activities were contracted out to the contract research organization (CRO), i.e. Sogo Rinsho Médéfi Co., Ltd. (Tokyo), and the study was initiated after the written operation procedures and protocols for individual study-related activities had been predefined.

With respect to data management activities, the CRO is responsible for developing an electronic data capture system in accordance with the Electronic Records and Electronic Signature Guidelines and for ensuring the quality of the data by managing the history of data entries by investigators and performing data verification using a data check program.

With respect to monitoring activities, the CRO was tasked with monitoring the study in accordance with the predefined monitoring plan. The monitoring activities that were performed during the study included confirming the signed informed consent form for all participants.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the patients, physicians, and medical staff who supported this study, including Yukie Okawara (Jichi Medical University) for the statistical analysis, and Sogo Rinsho Médéfi Co. Ltd. for the secretariat, data management, and monitoring.

Disclosure statement

This study was funded by Bayer Yakuhin Ltd. A conflict of interest between the company and the CARILLON Society, the study director, and other study-related individuals, including the principal investigators, was disclosed at the meetings of the Ethics and Conflicts of Interest committees. After an agreement on the clinical research was signed by the study director and Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd., it was decided that Bayer Yakuhin would fund the CARILLON trial.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103–2116.

- Horikawa T, Obara T, Ohkubo T, et al. Difference between home and office blood pressures among treated hypertensive patients from the Japan Home versus Office Blood Pressure Measurement Evaluation (J-HOME) study. Hypertens Res. 2008; 31:1115–1123.

- Ishikawa J, Kario K, Hoshide S, et al. Determinants of exaggerated difference in morning and evening blood pressure measured by self-measured blood pressure monitoring in medicated hypertensive patients: Jichi Morning Hypertension Research (J-MORE) Study. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:958–965.

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013;31:1281–1357.

- Shimamoto K, Ando K, Fujita T, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2014). Hypertens Res. 2014;37:253–390.

- Uno H, Ishikawa J, Hoshide S, et al. Effects of strict blood pressure control by a long-acting calcium channel blocker on brain natriuretic peptide and urinary albumin excretion rate in Japanese hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:887–896.

- Shimamoto K, Kimoto M, Matsuda Y, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of high-dose controlled-release nifedipine (80 mg per day) in Japanese patients with essential hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2015;38:695–700.

- Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:861–869.

- Hasebe N, Kikuchi K. Controlled-release nifedipine and candesartan low-dose combination therapy in patients with essential hypertension: the NICE Combi (Nifedipine and Candesartan Combination) Study. J Hypertens. 2005;23:445–453.

- Konoshita T, Makino Y, Kimura T, et al. A crossover comparison of urinary albumin excretion as a new surrogate marker for cardiovascular disease among 4 types of calcium channel blockers. Int J Cardiol. 2013;166:448–452.

- Kuga K, Xu DZ, Ohtsuka M, et al. Comparison of daily anti-hypertensive effects of amlodipine and nifedipine coat-core using ambulatory blood pressure monitoring - utility of 'hypobaric curve' and 'hypobaric area'. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2011;33:231–239.

- Fukutomi M, Hoshide S, Eguchi K, et al. Differential effects of strict blood pressure lowering by losartan/hydrochlorothiazide combination therapy and high-dose amlodipine monotherapy on microalbuminuria: the ALPHABET study. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2012;6:73–82.

- Kobayashi N, Ishimitsu T. Assessment on antihypertensive effect and safety of nifedipine controlled-release tablet administered at 80 mg/day in practical clinic. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2012;34:191–200.

- Webb AJ, Rothwell PM. Effect of dose and combination of antihypertensives on interindividual blood pressure variability: a systematic review. Stroke. 2011;42:2860–2865.

- Saito I, Saruta T. Controlled release nifedipine and valsartan combination therapy in patients with essential hypertension: the adalat CR and valsartan cost-effectiveness combination (ADVANCE-combi) study. Hypertens Res. 2006;29:789–796.

- Koulis C, Watson AM, Gray SP, et al. Linking RAGE and Nox in diabetic micro- and macrovascular complications. Diabetes Metab. 2015;41:272–281.

- Matsui T, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, et al. Nifedipine, a calcium channel blocker, inhibits advanced glycation end product (AGE)-elicited mesangial cell damage by suppressing AGE receptor (RAGE) expression via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385:269–272.

- de Lemos JA, Drazner MH, Omland T, et al. Association of troponin T detected with a highly sensitive assay and cardiac structure and mortality risk in the general population. JAMA. 2010;304:2503–2512.

- Folsom AR, Nambi V, Bell EJ, et al. Troponin T, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, and incidence of stroke: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Stroke. 2013;44:961–967.

- Wilson PW, Pencina M, Jacques P, et al. C-reactive protein and reclassification of cardiovascular risk in the Framingham Heart Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1:92–97.