Publication of a new guideline for the prevention, diagnosis and management of hypertension always generates huge interest among general physicians as well as hypertension specialists. In the last 10 years, American and European hypertension guidelines have become increasingly congruent on almost all aspects, including the definition of hypertension stages, therapeutic targets and therapeutic strategies to achieve blood pressure (BP) goals. This was a major advance as physicians and scientists used the same taxonomy and references to handle their patients with hypertension.

At the last meeting of the American Heart Association (AHA) in November, the new 2017 High Blood Pressure Clinical Practice Guidelines produced by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the AHA in collaboration with many other societies were presented [Citation1]. These recommendations provide major conceptual changes when compared to all previously published guidelines, including JNC7 [Citation2], the 2014 JNC8 committee report [Citation3] and the 2013 European Society of Hypertension(ESH)/European Society of Cardiology (ESC) hypertension guidelines [Citation4]. It is beyond the scope of this editorial to discuss all the differences between the 2017 AHA/ACC guideline and previous ones. However, a few important paradigm shifts deserve comments. These include: (1) the new definition of hypertension, which affects the prevalence of hypertension and its various phenotypes in the population, (2) the lower BP thresholds to start treating hypertension with drugs in high cardiovascular risk patients and (3) the lower BP goals for treated hypertensive patients.

1) The new 2017 ACC/AHA definition of hypertension

In JNC7, a change in BP categories was reported: the optimal BP values of <120/80 mmHg became the normal category; BP values of 120–139/80–89 mmHg were considered pre-hypertension, and all BP values above 160/100 mmHg were considered stage 2 hypertension. In JNC8, definitions of hypertension and pre-hypertension were not discussed, but thresholds for pharmacological treatments in various populations of hypertensive patients were defined. The 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines followed a similar approach, with definitions of hypertension stages and precise thresholds to start medical therapy according to age and comorbidities.

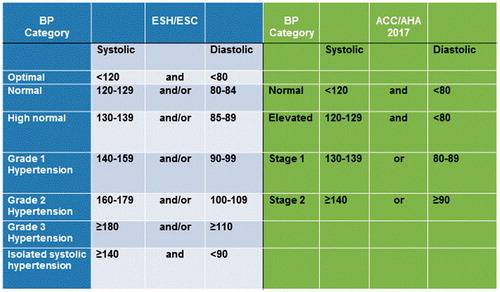

The new 2017 ACC/AHA guideline proposes a completely revised version of BP categories in hypertension. This revised categorization is illustrated in in comparison with 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines. According to this new guideline, normal BP is set at <120/80 mmHg and hypertension stage 1 starts at BP levels above 130/80 mmHg rather than 140/90 mmHg, as in the European guidelines. Of note, there is no stage 3 and the concept of isolated systolic hypertension, as mostly observed in elderly patients, disappears from the figure although it is mentioned later on as the most predominant form of hypertension in older adults. The new definitions have been influenced by the data from SPRINT and meta-analyses that included the SPRINT trial [Citation5]. The limitations of SPRINT have been commented on previously in Blood Pressure and will not be discussed again in this editorial [Citation6].

Figure 1. Comparison of blood pressure categories according to the ESH/ESC 2013 guidelines and the ACC/AHA 2017 recommendations.

This new classification will have a huge impact on the prevalence of hypertension in populations and consequently, on the number of patients who will use the health care system for blood pressure lowering treatment. When applied to the NHANES 2011–2014 data, this new classification will increase the prevalence of hypertension in the US by 14% to include 46% of the general adult population. Above the age of 65, at least 75% of men and women will be classified as hypertensive. The number of newly classified hypertensive persons eligible for treatment with antihypertensive medication should increase by only 2–3%, however, since those with stage 1 hypertension (BP 130–139/80–89 mmHg) and low cardiovascular risk are recommended to receive non-pharmacological treatment [Citation7]. These definitions may also impact the prevalence of white coat and masked hypertension.

2) Lower blood pressure thresholds to treat hypertensive patients

It is now widely accepted that the treatment of hypertension should be based not only on BP values but also according to the level of patients’ CV risk since there is a linear relationship between BP and the CV risk even at low BPs [Citation8]. Thus, the 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines recommend initiating antihypertensive drug treatment “in patients with grade 1 hypertension (140–159/90–99 mmHg) at low to moderate risk, … and remains within this range despite a reasonable period of time with lifestyle measures” [Citation4]. In patients with stage 2 and 3 hypertension rapid initiation of therapy is proposed, and elderly patients should be treated when their BP is above 160 mmHg systolic or lower levels (140 mmHg) if they are fit. Treatment can start with monotherapy in low risk patients and with single pill combinations in patients with higher CV risk.

A similar concept prevails in the ACC/AHA 2017 guideline, but at lower BP values and with a strong recommendation to use non-pharmacological therapies in patients with a 10-year CV risk of less than 10% and elevated BP or stage 1 hypertension (BP 120–139/80–89 mmHg) [Citation1]. This is designed to limit the initiation of drug therapy in persons previously considered as normotensive or pre-hypertensive. With either higher BP values or a higher CV risk, prompt initiation of drug therapy is recommended. However, for patients with elevated BP and those with stage 1 hypertension and a low CV risk, there is no clear indication on the therapeutic strategy to implement after the 6 months of non-pharmacological treatment when no change in BP has been observed and BP remains in the range of 130–139/80–89 mmHg. In our opinion, guidelines tend to overestimate the success rate of non-pharmacological strategies in the real world. Unless strategies such as losing weight, reducing alcohol consumption and reducing salt intake are implemented in the context of a formal program, a very low percentage of patients achieve the proposed objectives and maintain them over time. Moreover, one may question the safety of using pharmacologic combinations therapy in patients with a high CV risk and a BP of 120–129 mmHg systolic and <80 mmHg diastolic. At these BP levels, the risk of orthostatic hypotension is high [Citation9]. In addition, results of SPRINT have shown an increased incidence of adverse effects such as acute renal failure and electrolyte disturbances in patients treated to a BP target of <120 mmHg systolic [Citation5].

3) Lower BP goals for treated hypertensive patients: One size fits all?

One obvious consequence of changing the classification of hypertension is that the definition of adequate BP control changes as well. In the 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines, BP goals differed among different patient populations [Citation4]. Systolic BP targets were set at <140 mmHg for the general non-elderly hypertensive population, at <150 mmHg for the general elderly (>80 y) population, <140 mmHg for the fit elderly, <140 mmHg for patients with diabetes and <130 mmHg for patients with renal disease and proteinuria. Diastolic BP targets were set at <90 mmHg in all groups except in those with diabetes, where the target was <85 mmHg.

In the new ACC/AHA guideline, the target BP is <130/80 mmHg for all patients whatever their age and comorbidities, with the exception of prior stroke. Thus, it appears that “one size fits all” independently of age and comorbidities. The recommendation has the advantage of being simple but whether it is applicable to all hypertensive patients is a point of debate. Indeed, meta-analyses do not provide a strong evidence for a single target in all populations [Citation10]. The best example is the recommendation to lower BP <130/80 mmHg in patients with chronic kidney disease. Except SPRINT [Citation11], no other study or meta-analysis actually confirmed the benefits of lowering BP <130/80 mmHg on mortality in all CKD patients and none of the study including SPRINT found a significant effect of lowering BP <130 mmHg on renal disease progression [Citation10,Citation12].

In conclusion, the recent 2017 ACC/AHA guideline for prevention, detection, evaluation and management of hypertension in adults represents a major paradigm shift in our approach to hypertension. In the US, many individuals will be newly classified as hypertensive and be advised to adapt their lifestyles in order to normalize their BP to <120/80 mmHg. Whether this will occur and improve the global health of the American people remains to be demonstrated. On the positive side, the new guidelines are pragmatic and reflect good clinical practice in areas such as blood pressure measurement and the diagnosis of secondary forms of hypertension. One particularly important recommendation is summarized in the slogan “Know your blood pressure”, encouraging physicians to communicate their BP values to their patients whenever measured in order to reinforce patients’ involvement in their care and increase their adherence to pharmacologic and lifestyle modification therapies.

Finally, when the term “pre-hypertension” was introduced and the thresholds of treatment were reduced, Prof. T.J. Pickering wrote two editorials with provocative title, which are well suited to the actual situation. The first was “Lowering the thresholds of disease—are any of us still healthy?” and the second one was entitled “Now we are sick: labeling and hypertension” [Citation12,Citation13]. These two editorials raise some important questions. One of these concerns the effect of labeling individuals as hypertensive when they have low CV risk and BPs below levels that are currently considered hypertensive. Labeling has been shown to increase use of the health care system, absenteeism from work, as well as depression, independently of the level of BP or its treatment [Citation14]. Another relevant question is whether emphasizing treatment of patients with low CV risk and high normal (renamed elevated) BP will not distract physicians from their major job, i.e. to care appropriately for hypertensive patients at high CV risk. Considering that today only half of those with hypertension are treated and less than half of those who are treated are on target [Citation15].

Disclosure statement

MB, SO, KN and SEK are editors of Blood Pressure and report no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose related to this commentary.

References

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: a Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2017 Nov 13. pii: HYP.0000000000000066. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066. [Epub ahead of print].

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252.

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507–520.

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2159–2219.

- Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. SPRINT Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103–2116.

- Kjeldsen SE, Narkiewicz K, Hedner T, et al. The SPRINT study: Outcome may be driven by difference in diuretic treatment demasking heart failure and study design may support systolic blood pressure target below 140 mmHg rather than below 120 mmHg. Blood Press. 2016;25:63–66.

- Muntner P, Carey RM, Gidding S, et al. Potential U.S. Population Impact of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association High Blood Pressure Guideline. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 6. pii: S0735-1097(17)41474-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.073. [Epub ahead of print].

- Vasan RS, Larson MG, Leip EP, et al. Impact of high-normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:1291–1297.

- Bress AP, Kramer H, Khatib R, et al. Potential deaths averted and serious adverse events incurred from adoption of the SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) intensive blood pressure regimen in the United States: Projections from NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey). Circulation. 2017;135:1617–1628.

- Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:957–967.

- Cheung AK, Rahman M, Reboussin DM, et al. Effects of intensive BP control in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:2812–2823.

- Xie X, Atkins E, Lv J, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:435–43.

- Pickering TG. Lowering the thresholds of disease-are any of us still healthy? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2004;6: 672–674.

- Pickering TG. Now we are sick: labeling and hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2006;8:57–60.

- Rahimi K, Emdin CA, MacMahon S. The epidemiology of blood pressure and its worldwide management. Circ Research. 2015;116:925–936.