Abstract

Purpose: Recognition of clinical inertia is essential to improve the control of chronic diseases. Although it is very intuitive, a better interpretation of the concept of clinical inertia is lacking, likely due to its high complexity.

Materials and Methods: After a review of the published articles, we propose a practical vision of inertia, contextualized within the clinical process of hypertension care.

Results: This new vision enables the integration of previous terms and definitions of clinical inertia, as well as proposing specific strategies for its reduction.

Conclusion: Although some concepts should be considered as ‘justified inertia’ or ‘investigator inertia’, the idea that inertia may be present throughout the continuum of care gives physicians a holistic view of the problem that is easily applicable to their clinical practice. Measures to overcome inertia are complicated because of the intrinsic complexity of the concept.

Introduction

Hypertension is the leading cause of death worldwide. High blood pressure has a direct relationship with cardiovascular disease (CVD), a high prevalence in the population and different therapeutic options available for its control, making this cardiovascular risk factor the cornerstone of strategies to improve the general health of the population by reducing the incidence of cardiovascular events. The main hypertension guidelines indicate that the benefit derived from the detection and control of hypertension has a high degree of evidence through a very simple procedure, which is blood pressure (BP) measurement during medical consultation of all persons who contact the health system regardless of the initial reason for their visit [Citation1–3].

Management of hypertension should be understood as a dual cardiovascular continuum. Considering the pathophysiology, it is clear that hypertension is much more than simply an increase in BP values. From high BP to symptomatic CVD, the patient passes through different stages along the cardiovascular continuum, ranging from a healthy asymptomatic individual at risk of developing hypertension to the development of symptomatic CVD, passing through hypertensive subjects with and without target organ damage (TOD). In this continuum the reversibility of the process is reduced over time. It should also be noted that the negative cardiovascular effect of sustained high BP is not the only factor in the progression along the cardiovascular continuum, as there is a common association between hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors, with a negative synergistic effect on the vascular system of the individual. As a consequence, we should not only address and treat high BP values, but also the overall cardiovascular risk of the individual [Citation4,Citation5].

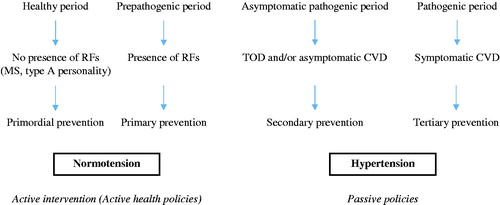

The cardiovascular continuum has two direct clinical consequences. First, it is essential to detect high BP values as early as possible to avoid disease progression; and second, there is a need for precise individual phenotyping, because depending on the stage at which each individual is, different therapeutic and objective measures must be implemented () [Citation4]. In line with these observations, for correct individual phenotyping, associated comorbidities (TOD and CVD) should be actively pursued and individual therapeutic objectives and strategies set in accordance with the current indications as established in the clinical care process for hypertension [Citation6].

Figure 1. Natural history of hypertension and corresponding prevention strategies. Abbreviations: CVD: cardiovascular disease; MS: metabolic syndrome; RF: risk factors; TOD: target organ damage.

Despite the importance of adequate early diagnosis and proper control of hypertension, it is universally accepted that there is a high proportion of undetected hypertension and a moderate degree of control [Citation7]. The factors explaining this are complex and, although they have been widely studied, not all of them are well known and understood. Some of these factors are related to the nature of hypertension itself (intrinsic factors), and others are related to how hypertension is managed in daily practice (extrinsic factors) [Citation8]. Clinical inertia is one of the most important extrinsic factors, due to its high prevalence and potential subsequent correction once detected.

Clinical inertia, an evolutionary concept

Despite its apparent simplicity, the definition of clinical inertia is complex. A simplification of the definition of inertia could perhaps be summarized with the following sentence: everyone should do what is appropriate according to the available evidence and when this does not occur, inertia is present. However, this is a definition that must be developed, not only in daily clinical practice, but also in the academic and research world.

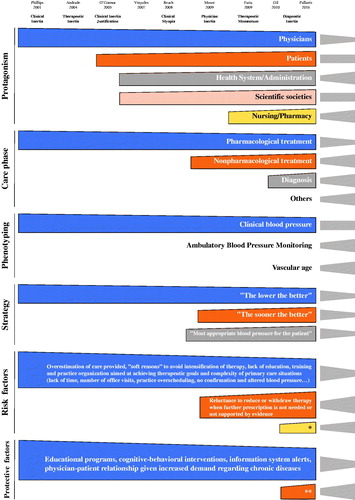

In 2001, Phillips introduced the first definition of the term as the failure of physicians to initiate or intensify treatment when indicated [Citation9]. Since this first publication, an increasing number of publications have followed () and, in association, an increase in articles proposing different terms (such as therapeutic inertia, healthcare-provider inertia, or clinical shortsightedness) and new definitions of inertia. Although this has had an apparent positive consequence (consideration of different aspects of clinical inertia), uncertainty and much confusion has also been generated among physicians and the rest of the scientific community. In addition, the absence of a measurement tool for inertia adds further difficulty to its applicability.

Table 1. Clinical inertia concept historical evolution through the literature (modified from Lebeau et al, [Citation12]).

To illustrate the difficulty mentioned above, in some instances decisions may be made in clinical practice that could be considered clinical inertia, but which are made based on appropriate clinical practice for a specific patient (apparent clinical inertia) [Citation10]. For this reason, some authors propose the concept of ‘true clinical inertia,’ establishing as necessary for this condition: (a) the existence of an implicit or explicit guideline on the health problem of the patient; (b) the knowledge of clinical practice guidelines by the physician; (c) the belief of the physician that the guideline applies to the patient or specific group of patients in which the patient would be classified; (d) the physician has the resources to apply the guideline. Under this proposal, inertia only applies when none of the above conditions are met [Citation11]. From a clinical perspective, this is very important, as the usual approach in the treatment of chronic diseases, and hypertension in particular, is to move into the realm of "apparent clinical inertia" and, clearly, this is an additional difficulty for the assessment of inertia in real-world clinical practice.

Review of the main publications on the concept and the definition by Phillips allows us to highlight some aspects of the evolution that, evidently, has not concluded [Citation9,Citation12–21] and, in fact, continues to evolve: (a) Clinical inertia should be considered at any stage of the clinical care process for hypertension, not only in the therapeutic stage, as is usually the case; (b) Contrary to the general idea that only physicians are responsible for inertia, responsibility is shared with all participants in the clinical care process, including patients, pharmacists, nurses, health authorities, scientific societies and the pharmaceutical industry [Citation22]; (c) Beyond an accusatory and negative view of inertia, a more positive view emerges, due to greater understanding of the multiple causes and determinants of inertia and, consequently, a willingness to develop a strategy in clinical practice to overcome clinical inertia, and to improve control of BP and quality of care.

Our view of clinical inertia in hypertension

Considering the abovementioned reasons, our aim is to clarify the definition and concept of clinical inertia in hypertension to offer a new practical and applicable perspective from our experience and the main published proposals.

To obtain an overall perspective of clinical inertia and its conceptual definition, two authors (VP and IB) conducted a search of the MEDLINE database through the Pubmed portal using the terms “clinical inertia” and “hypertension”. Publications included dated from the study by Philips et al. in 2001 [Citation9], the initial creator of the concept of clinical inertia, until December 2016. An initial abstract reading of 149 publications was conducted by the same authors (VP and IB). Publications selected used the new definition or conceptual interpretation of clinical inertia (n = 28). When a research group had more than one eligible publication, the most relevant was selected as representing a new point of view regarding clinical inertia (n = 20). Reading of the complete text of the initially selected publications was performed by all the authors. The final list of publications to be analyzed was chosen by consensus among all the authors (13). Discrepancies were resolved after consultation with national Spanish experts on hypertension (n = 9).

Considered as a whole, the different proposals to define inertia most likely illustrate different aspects of the problem with complementary terms and points of view that allow a broader and enriching view of clinical inertia in hypertension. The proposal put forward is to simplify the situation to facilitate the easy recognition of inertia as a way to improve the control of BP. With this objective, we propose a new, more holistic concept, based on the pathophysiological and clinical aspects of hypertension, contextualizing clinical inertia in the cardiovascular continuum (from asymptomatic hypertensive patients without TOD to those with patent CVD) (), the clinical care process for hypertension (from primary to tertiary prevention) and the actions to be taken depending on the stage of the patient, as shown in : universal preventive screening with BP measurement in all patients who seek health system services for any reason, regardless of the purpose of the visit; confirmation of the diagnosis after high initial BP values are detected; individualized study of each hypertensive patient to evaluate the possibility of secondary hypertension and to establish goals for control, with therapeutic strategies depending on the estimation of the individual overall cardiovascular risk; and finally, to monitor in the long term with the periodicity and examinations established by the clinical practice guidelines [Citation1–3].

Table 2. Clinical care process in hypertension and its relationship with clinical inertia.

Against the generalized idea of clinical inertia in which the majority of physicians consider it to refer only to the stage of therapeutic follow-up in the clinical care process, the proposal advanced here is based on the idea that inertia can be present in every aspect of care of the hypertensive patient, including nonpharmacological decisions. It is also interesting to consider the recently described “investigator inertia”, defined as the situation in which antihypertensive medications are not modified in a patient participating in a clinical trial, even though the patient has uncontrolled BP according to the protocol. As a consequence, the demonstrated efficacy of the studied intervention is falsely lower than the true efficacy [Citation23].

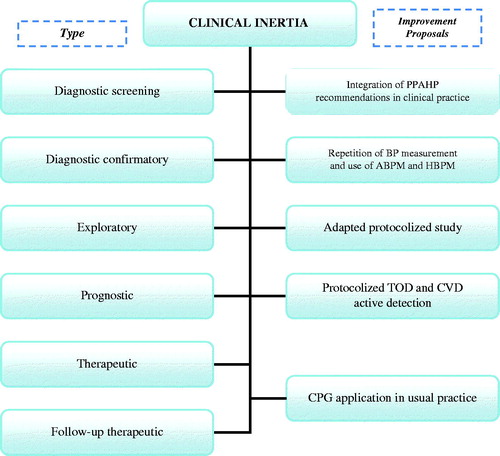

With the basic ideas described above, in the proposed model we consider different types of clinical inertia ().

Figure 2. Types of clinical inertia depending on the clinical care process stage and our proposals for improvement. Abbreviations: ABPM: ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; BP: blood pressure; CPG: clinical practice guidelines; CVD: cardiovascular disease; HBPM: home blood pressure measurement; PPAHP: Program of Preventive Activities and Health Promotion; TOD: target organ damage.

Diagnostic screening clinical inertia

In accordance with the scheme of the clinical care process, primordial prevention is the first step comprising the promotion of healthy lifestyle changes aimed at the entire population. Primary prevention is the second step and is based on strategies aimed at those identified as having a greater risk of developing hypertension in the future, such as normotensive patients with obesity. Due to the high prevalence of hypertension in the general population, the ideal in clinical practice would be the recommendation of healthy hygiene and dietary habits for the entire population and the detection of the population at risk of developing hypertension, taking advantage of any opportunity during a physician visit, independent of the initial reason for consultation [Citation24].

Although such nonpharmacological measures are the basis for the treatment of hypertension at all stages of the disease, regardless of the cardiovascular risk factor and/or associated clinical disease, when considering clinical inertia it should be noted that there are few studies on nonpharmacological treatment in which the situation of the patient indicates prescribing weight loss, exercise and smoking cessation, extending the concept of inertia to other health professions [Citation25].

‘Screening inertia’ is a type of diagnostic inertia that is present when the BP values are high using the preventive activity of taking the BP but these values are not considered indicators of hypertension in the patient and, as a consequence, the results are not confirmed by repeated measurements according to the indications in the clinical practice guidelines [Citation1–3].

Confirmatory diagnostic clinical inertia

A second type of diagnostic inertia is ‘confirmatory inertia,’ which is observed when elevated BP is obtained at two separate visits by two consecutive measurements in each visit [Citation2], but the diagnosis of hypertension is not confirmed by home BP measurement (HBPM), ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) or subsequent office BP measurements.

Both screening and confirmatory diagnostic inertia may be due to due to a number of different reasons. Some are intrinsic to the complex nature of hypertension, such as the individual variability of BP values, white coat phenomenon or masked hypertension. Others are extrinsic and potentially correctable. When considering extrinsic factors for diagnostic inertia, the main errors are two: the methodology applied for BP measurement and its interpretation. A common example of inaccurate measurement is the use of instruments that are not validated or are incorrectly calibrated. Sometimes, although the methodology for measuring BP is appropriate, physicians have concerns about the reliability of the values obtained, generally arguing difficult conditions in their clinical practice for measuring BP according to the guideline recommendations. This situation generates uncertainty in clinicians regarding the reliability of the BP reading. These are all factors involved in accepting borderline BP values as appropriate rather than diagnosing hypertension. We should now reiterate the concept of ‘justified clinical inertia.’ This is a frequent situation in individuals with multiple conditions and/or elderly people, both groups with a high prevalence of hypertension and an elevated cardiovascular risk. When physicians detect grade 1 hypertension in individuals with multiple conditions, they sometimes prefer not to add another diagnosis and more drugs in order to maintain therapeutic adherence, believing that the beneficial effect of controlling BP may be smaller than the overall benefit sought. This is also very common in older people, in whom hypertension is mainly due to a progressive increase in the systolic component, usually combined with low diastolic BP and a higher prevalence of white coat hypertension [Citation26]. For this reason some doctors prefer not to initiate treatment until BP values are much higher than the current recommendations suggest [Citation1–3]. At times, the recognition of these methodological limitations and the opinion that the onset/intensification due to the possibility of potentially negative effects of short-term drug treatment is greater than the benefit are the arguments that some physicians put forward for not diagnosing hypertension. As mentioned previously, ‘justified clinical inertia’ would not be considered a true inertia [Citation10,Citation11], an aspect difficult to evaluate in studies. Another similar diagnostic inertia is the result of uncertainties or reservations about the recommendations of clinical practice guidelines. This situation has been seen in recent years as a consequence of the proliferation of multiple guidelines with different recommendations, as well as the continuous publication of evidence that is at times conflicting and at a speed that is too rapid for clinicians to internalize [Citation27]. Concerning hypertension, there has been recent controversy over BP values due to the differences between the objectives proposed by the European Societies of Hypertension and Cardiology (2013 and 2018) and those proposed in 2017 by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology [Citation1,Citation3,Citation28,Citation29]. These uncertainties are especially important in the aged population [Citation30].

There is an intrinsic limitation in the diagnosis of hypertension that arises from the definition of this condition being based on the detection of a usually inexact phenotype, consisting of finding values higher than the established BP standards. This has the theoretical advantage of its accessibility (although, as shown, this is not usually the case in clinical practice) and low cost. Nonetheless, as stated above, it is easy to illustrate the intrinsic limitations of this parameter given its high physiological variability, as demonstrated by the fact that almost one third of diagnosed hypertension is white coat hypertension [Citation31–33]. As a result, hypertension can be erroneously diagnosed, exposing people to complementary examinations or unnecessary treatments [Citation34]. We also know that the opposite phenomenon, masked hypertension, occurs in approximately 10% of the population [Citation31,Citation32]. For these reasons, it is always necessary to confirm the initial diagnosis of hypertension by repeated measurements of clinical BP and, in some instances, using HBPM and/or 24-h ABPM. Both HBPM and ABPM have been shown to be cost-effective and, according to the 2016 Spanish guidelines [Citation2], should be used to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension, except in cases requiring immediate treatment due to very high BP values or very high cardiovascular risk [Citation30,Citation32].

Exploratory clinical inertia

According to the third stage of the clinical care process, secondary hypertension must be considered and a more precise phenotype obtained of each subject along the pathophysiological cardiovascular continuum.

To explore the possibility of secondary hypertension, it is essential to have a practical and cost-effective protocol for differential diagnosis between essential and secondary hypertension. At this point, we can use the term ‘exploratory clinical inertia’ when a structured protocol for the screening of secondary hypertension is not applied in at-risk patients: those with hypertension that is refractory or when onset is at extreme ages of life, or those with rapid development of hypertension and/or TOD. Given the low prevalence of secondary hypertension, protocols should be based on basic diagnostic parameters, with evidence that their systematic application is cost-effective, and always bearing in mind that, following the suspicion of secondary hypertension, in certain clinical settings, some diagnostic procedures may be difficult to implement [Citation35].

The second objective of the exploratory stage is to establish the individual long-term prognosis of each hypertensive patient in order to design the best therapeutic objectives and strategies to achieve them. We must remember that this is still within the asymptomatic pathogenic period and the fourth stage of the clinical care process. The goal is to obtain the most accurate individual phenotype to place the patient at the most precise point on the cardiovascular continuum, in order to establish the long-term prognosis and the risk of having a future cardiovascular event. To do this, the individual overall cardiovascular risk must be estimated by applying a risk estimation table, validated for the local population. This is done by assessing not only clinical BP, but also TOD and establishing subclinical disease and the coexistence of other cardiometabolic risk factors.

Prognostic clinical inertia

Prognostic inertia is present when the overall estimate of individual cardiovascular risk in each hypertensive patient is not calculated. Hypertensive patients with increased cardiovascular risk, TOD (subclinical lesion) or evidence of CVD, need stricter control and intensive treatment. However, some studies find that physicians often underestimate the overall individual cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients, sometimes because a comprehensive strategy for exploring the presence of asymptomatic TOD or CVD is not actively pursued [Citation22,Citation36].

We can conclude that ‘exploratory clinical inertia’ is present when the study of the hypertensive patient does not consider the possibility of secondary hypertension or when TOD and overall individual CVD risk are not actively assessed to establish a potential long-term prognosis.

Therapeutic clinical inertia

Once the prognosis is determined, we must establish individual therapeutic goals and select the best treatment for the patient based on the scientific evidence. As previously mentioned, therapeutic goals should consider not only BP values, but also the goals for other cardiovascular risk factors, as well as the presence of TOD and established CVD. In general, the therapeutic objectives and intensity of treatment should be directly proportional to the overall cardiovascular risk.

Once the goals have been defined, treatment should be initiated. The decision should always be based on hygiene, dietary and lifestyle measures, together with pharmacological treatment when indicated. ‘Therapeutic clinical inertia’ occurs when the choice of treatment is not the most appropriate according to the clinical condition of the patient and the recommendations of the clinical practice guidelines. At times, although a correct and accurate prognosis has been made, the intensity of treatment is not adequate to achieve the objectives, usually due to the belief that possible short-term side effects outweigh long-term benefits. This is the type of inertia that can most frequently be 'justified' [Citation10,Citation11]. To distinguish this situation from ‘true clinical inertia,’ the main criterion would be a justification written directly into the medical history of the patient by the physician.

Follow-up clinical inertia

In accordance with the clinical care process, we define ‘follow-up therapeutic inertia’ as the situation in which treatment is not intensified or modified when the objectives in the periodic follow-up of the patient are not achieved, or follow-up is not carried out with the periodicity or examinations established by the clinical practice guidelines. In addition, it is important to evaluate whether the minimum number of BP measurements have been carried out at each visit during follow-up. As evidence of the importance of this type of inertia, it has been shown that, despite poor control, physicians need 2–3 years to intensify treatments of cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension [Citation37].

In comparison with the initial concept of clinical inertia in our proposal [Citation9], the failure by physicians to initiate treatment corresponds to diagnostic clinical inertia and the failure to intensify or modify treatment once it has begun is what we consider follow-up therapeutic inertia.

Factors that may encourage inertia in the care process

Each clinical practice situation in primary care (as well as in specialized care) has specific characteristics. However, in all cases there are common issues that can lead to inertia at each of the stages analyzed. Among the most frequent causes we find: lack of motivation among professionals, lack of familiarity with clinical practice guidelines or consensus, insufficient completion of the medical history, frequent change of doctor, saturation of consultations (increased pressure on healthcare personnel results in less time for prevention), lack of training in proper drug management (dose escalation, use of combinations, control targets, etc.), and finally, the lack of credibility of the message by the doctor can generate refusal, rational or irrational, by the patient to take the treatment correctly. All of the above implies that a risk factor such as hypertension that is not adequately controlled in initially low-risk and easily controlled patients will evolve along the cardiovascular continuum, and patient risk will increase (TOD) until the possible occurrence of a cardiovascular event. This will increase healthcare costs that could have been avoided by providing a diagnosis and treatment from the earliest possible time. In fact, the most recent hypertension guidelines in Europe [Citation29] are stricter regarding the objectives to be achieved (depending on patient risk), and according to the guidelines of American cardiology societies (American College of Cardiology / American Heart Association) the criterion for stage 1 hypertension is systolic blood pressure between 130–139 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure between 80–89 mmHg [Citation3].

Potential solutions to overcome clinical inertia in the management of hypertension from a new point of view

Due to the difficulties discussed earlier stemming from the absence of a universally accepted definition of inertia, coupled with its high complexity and the different collectives involved [Citation10], it is not easy to establish clear and definitive solutions to reduce inertia in daily clinical practice [Citation11,Citation38]. Based on our proposal for a holistic concept of clinical inertia, we suggest some realistic solutions to overcome inertia in daily clinical practice (). Nonetheless, more research is needed to measure benefit or to assess the best strategies for overcoming inertia.

Figure 3. Conceptual map of the evolution of the term “inertia in hypertension” and its constituent elements. Across the top of the figure are listed the authors and publications that have brought about a significant change in the conceptual evolution of clinical inertia in hypertension. The length of the colored rectangles corresponds to when each topic was first mentioned in the scientific literature (reference). The color has no associated definition and is included to aid in interpreting the figure. The shape of the rectangles represents the evolution (ascending as weight increases over time, descending as weight decreases over time, neutral unchanged). The geometric shapes in grey represent the foreseeable future evolution. *All these causes of clinical inertia at any phase of the clinical care process, clinical inertia in relation to pharmacological but also to nonpharmacological treatment, inaccurate individual phenotyping, not looking for target organ damage. **Develop telemedicine and electronics for correct phenotyping and diagnosis, involve other health professionals, scientific societies and the Health Administration, integrate Program of Preventive Activities and Health Promotion recommendations in clinical practice, repeat blood pressure measurement and use ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and home blood pressure measurement, conduct an adapted protocolized study, protocolized target organ damage and active cardiovascular disease detection, and consider application of clinical practice guidelines in usual practice.

In general, knowledge of the main clinical practice guidelines is considered to be inversely related to the incidence of clinical inertia. However, knowledge of the guidelines is insufficient for physicians, mainly because each standard recommends different values for diagnosis, as is the case of the two main hypertension guidelines [Citation1,Citation3]. The guidelines should perhaps be clearer, with less time between each reevaluation and with a prior consensus among the major endorsing medical societies [Citation26,Citation27].

For screening and confirmatory diagnostic inertia, one solution could be to adopt just one set of international recommendations [Citation1,Citation3] and the Spanish national adaptation [Citation2], to adequately confirm an altered clinical BP and apply the recommended follow-up in the case of normal screening in at-risk individuals. Adopting the criteria of the guidelines and their adaptation to the Spanish population may be a good option [Citation2] as these are specifically aimed at primary care professionals, and their supranational nature has the advantage of providing general recommendations with the possibility of specific modifications for each different geographical area. According to these guidelines, the values for the diagnosis of hypertension during an office visit are ≥140/90 mmHg after an accurate measurement.

Some authors have shown that one way to improve screening and confirmatory diagnostic inertia in the general population may be through the determination of BP in organized groups. An example of this is workplace check-ups, which are carried out periodically through prevention services provided by mutual insurance companies, as an active way of increasing diagnosis in asymptomatic subjects [Citation39,Citation40].

Some physicians express uncertainty about the reliability of the BP values obtained, mostly related to methodological limitations. Again, proper periodic training on the correct methodology and interpretation of the BP measurement should be considered. The use of ABPM is one way to improve the multiple limitations of measurement at the clinic [Citation29,Citation33,Citation41]. Another benefit of its use in confirming the diagnosis is the possibility of detecting white coat and masked hypertension [Citation32]. In addition, ABPM has been associated with a decrease in clinical inertia. [Citation41,Citation42].

Secondary hypertension requires the implementation of evidence-based protocols, adapted to local capabilities. Given its low prevalence, a realistic approach to requesting complementary tests will be very important, to ensure they are truly feasible in the care setting. These tests should always be based on a thorough anamnesis and physical examination as a cornerstone for detection, avoiding overuse of radiological and analytical tests without a prior degree of suspicion [Citation35]. It is also very important to avoid ‘exploratory clinical inertia’ when considering overall cardiovascular risk, especially when TOD should be actively examined. However, the issue is to determine which complementary tests should be performed, as it is widely known that the inclusion of an increasing number of tests increases the overall cardiovascular risk of hypertension compared to the use of the traditional cardiovascular risk factors. The adoption of a protocol involving primary care and hospital care is the solution. This protocol should clearly establish the complementary tests to be performed and for which patients, as well as which table for the overall estimation of cardiovascular risk is the best for each specific population. These considerations can also be applied to overcome ‘prognostic clinical inertia.’

Regarding ‘therapeutic clinical inertia,’ strong recommendations should be made for individualized therapeutic goals to be specified and recorded in the clinical history of each patient, not only for BP but also for all cardiovascular risk factors requiring control targets, as well as TOD markers [Citation43]. Similarly, it is very important to explain to the patient the objective to be achieved and the importance of proper adherence. For this, clinical practice guidelines are needed that express clear therapeutic objectives and thus avoid uncertainty [Citation28,Citation44]. The use of predefined materials could be of interest to explain to the patient the therapeutic strategies to be achieved and their purpose. For this reason and to empower the patient, nursing personnel must play a greater role [Citation45].

Some authors have established a direct relationship between the suspicion of nonadherence on the part of the doctor and their resistance to increasing antihypertensive treatment when it is indicated. Physician assessment of the true adherence of each patient could likely be a solution for intensifying treatment in uncontrolled BP control, as shown in the study by Kronisch [Citation46], in which the sharing of electronically measured adherence data was significantly associated with less ‘therapeutic clinical inertia’ (31% for the intervention group and 66% for the control group). This experience also shows the potential benefit of using new technological strategies in the management of hypertension [Citation47].

Finally, chronic hypertension and its progression over time, the need for periodic visits, complementary tests and updating of goals are understood. The periodicity and interventions to be performed should be scheduled for each hypertensive patient at the time of detection of the disease, if not ‘follow-up therapeutic inertia’ occurs. Again, the intensity of follow-up and treatment should be proportional to the cardiovascular risk of each patient. To improve patient involvement and awareness, the implementation of ABPM should always be considered.

Due to greater access of the population to certain healthcare collectives, it is very important to incorporate the participation of nurses and also of the community pharmacy not only in BP measurement [Citation48], but also in the use of techniques such as ABPM, the ankle-brachial index or more sophisticated measurements, such as arterial stiffness [Citation49], all after proper training.

A shared electronic medical record is essential for a multidisciplinary, patient-centered team strategy, where all information is available to all professionals and facilitates interaction. At this stage it is vital to have alerts in the clinical history that indicate to the health professional the poor control of the patient. The greater availability of mobile phones with the possibility of using applications would encourage, in those patients who are familiar with their use, greater participation and better management of their hypertension. Furthermore, remote consultation for hypertensive patients may make it possible to extend the time between office visits when necessary, which would reduce clinical inertia [Citation50].

Reducing inertia as a way to improve BP control is a priority. To accomplish this, a conceptual and cultural change in the management of hypertension is essential for a new organizational structure in the management of hypertension, as well as other chronic diseases [Citation39]. The recognition by all the protagonists that clinical inertia may be present at each stage of the clinical care process is crucial for change to take place. In addition, the development of telemedicine and mobile devices that are becoming increasingly prevalent and at a lower cost opens up the possibility of their widespread use in daily clinical practice.

Cultural change is the first necessary step towards a global organizational change through which patients, nurses and community pharmacies can enhance their role through the implementation of new technologies in daily clinical practice [Citation47]. The study by Crowley of 296 patients monitored by nurses [Citation51] is of interest. When the mean 2-week home BP of a patient was elevated, an 'intervention alert' would reach physicians who could then consider intensifying treatment. The patients generated 1216 intervention alerts during the 18-month intervention. Of 922 eligible intervention alerts, study physicians intensified treatment in 374 instances (40.6%). The perception by the physician that the HBPM was acceptable was the most common reason for lack of intensification (53.7%). When 'acceptable BP' was the reason for not intensifying treatment, the mean BP was lower than for the intervention alerts (135.3/76.7 compared to 143.2/80.6 mmHg; p < 0.001). Acceptable BP intervention alerts were associated with a lower incidence of repeated alerts, meaning that HBPM was lower, despite apparent clinical inertia. This telemedicine intervention aimed at clinical inertia did not guarantee treatment intensification in response to an elevated HBPM. However, when physicians did not intensify treatment, this was because the BP was closer to an acceptable threshold and repeated BP rises occurred less frequently. Lack of treatment intensification when the HBPM is elevated can sometimes represent good clinical judgment rather than clinical inertia, the previously mentioned “justified clinical inertia”, which should not be considered “true clinical inertia”.

Conclusions

The reflection we have carried out allowed us to consider clinical inertia as a dynamic phenomenon in its conceptual evolution, as well as throughout the different pathophysiological and care stages of hypertension. Although this evolution causes confusion that interferes with recognition of inertia in daily clinical practice, it has also shown an increase in related aspects, with the need to recognize and distinguish 'justified clinical inertia.' Our holistic model could help identify clinical inertia throughout the pathophysiological and clinical stages of hypertension, as it is a practical tool for the detection and management of inertia in daily clinical practice as part of the ongoing process of quality of care. This is important not only for daily clinical practice, but also in the development of clinical trials, in which the existence of “investigator inertia” is frequent.

The great complexity of clinical inertia relates to the fact that not only physicians, but also patients, other health professionals, health authorities and medical and scientific societies promoting clinical guidelines are all responsible for inertia and its solutions. The solutions require a broader knowledge and not only the acceptance of guideline recommendations. Today, partly due to the growing number of hypertensive patients and also to the increased availability and reliability of electronic devices for better phenotyping of individual BP, organizational changes are needed that include greater integration of nursing, community pharmacy and patients themselves as protagonists, all as part of effective and realistic solutions for clinical inertia. There is a clear need for greater evidence on the efficacy and effectiveness of these new proposals and organizational models and to consider inertia as a dynamic and holistic problem that can be encountered at any stage of the clinical care process.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gretchen Swasey, Maria Repice and Ian Johnstone for their help with the English version of the text.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013;31:1281–1357.

- Maiques Galán A, Brotons Cuixart C, Banegas Banegas JR, et al. Recomendaciones preventivas cardiovasculares. PAPPS 2016. Aten Primaria. 2016;48:4–26.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:e127–e248.

- Dzau V. The cardiovascular continuum and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade. J Hypertens Suppl. 2005;23:S9–S17.

- Hanefeld M, Pistrosch F, Bornstein SR, et al. The metabolic vascular syndrome. Guide to an individualized treatment. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2016;17:5–17.

- Olsen MH, Angell SY, Asma S, et al. A call to action and a lifecourse strategy to address the global burden of raised blood pressure on current and future generations: the Lancet Commission on hypertension. Lancet. 2016;388:2665–2712.

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement studies with 19.1 million participants. Lancet. 2017;389:37–55.

- Rodríguez-Roca GC, Pallarés-Carratalá V, Alonso-Moreno FJ, et al. Working group of arterial hypertension of the Spanish Society of Primary Care physicians (Group HTA/SEMERGEN); PRESCAP 2006 investigators. Blood pressure control and physicians' therapeutic behavior in a very elderly Spanish hypertensive population. Hypertens Res. 2009;32:753–758.

- Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:825–834.

- Aujoulat I, Jacquemin P, Rietzschel E, et al. Factors associated with clinical inertia: an integrative review . Adv Med Educ Pract. 2014;5:141–147.

- Reach G, Pechtner V, Gentilella R, et al. Clinical inertia and its impact on treatment intensification in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 2017;43:501–511.

- Lebeau JP, Cadwallader JS, Aubin-Auger I, et al. The concept and definition of therapeutic inertia in hypertension in primary care: a qualitative systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:130.

- Okonofua EC, Simpson KN, Jesri A, et al. Therapeutic inertia is an impediment to achieving the Healthy People 2010 blood pressure control goals. Hypertension. 2006;47:345–351.

- Vinyoles E. No sólo inercia clínica…. Hipertensión (Madr). 2007;24:91–92.

- Moser M. Physician or clinical inertia: what is it? Is it really a problem? And what can be done about it?. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2009;11:1–4.

- Reach G. Patient non-adherence and healthcare-provider inertia are clinical myopia. Diabetes Metab. 2008;34:382–385.

- Faria C, Wenzel M, Lee KW, et al. A narrative review of clinical inertia: focus on hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3:267–276.

- Rodrigo C, Amarasuriya M, Wickramasinghe S, et al. Therapeutic momentum: a concept opposite to therapeutic inertia. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:97–98.

- Gil-Guillén V, Orozco-Beltrán D, Márquez-Contreras E, et al. Is there a predictive profile for clinical inertia in hypertensive patients?. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:981–992.

- Palazón A, Gil V, Orozco D, et al. Is the physician's behavior in dyslipidemia diagnosis in accordance with guidelines? Cross-sectional ESCARVAL study. PLoS One 2014;9:e91567.

- Pallarés V, Bonig I, Palazón A, et al. Steering Committee ESCARVAL Study. Analysing the concept of diagnostic inertia in hypertension: a cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pract 2016;70:619–624.

- Redón J, Mourad JJ, Schmieder RE, et al. Why in 2016 are patients with hypertension not 100% controlled? A call to action. J Hypertens. 2016;34:1480–1488.

- Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Dahlöf B, et al. Physician (investigator) inertia in apparent treatment-resistant hypertension. Insights from large randomized clinical trials. Lennart Hansson Memorial Lecture. Blood Press. 2015;24:1–6.

- Appel LJ. Lifestyle modification as a means to prevent and treat high blood pressure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14: S99–S102.

- Bock C, Diehl K, Schneider S, et al. Behavioral counseling for cardiovascular disease prevention in primary care settings: a systematic review of practice and associated factors. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69:495–518.

- Bulpitt CJ, Beckett N, Peters R, et al. Response to HYVET ambulatory blood pressure substudy. Hypertension. 2013;61:e43

- Giner V, Esteban MJ, Pallarés V. Overview of guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia: EU perspectives. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2016;12:357–369.

- Giner V, Vicente D, Esteban MJ. Is lower still better? Reflections on Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial Study. Med Clin (Barc). 2016;147:127–129.

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group; 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3021–3104.

- Ferri C, Ferri L, Desideri G. Management of hypertension in the elderly and frail elderly. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev. 2017;24:1–11.

- Fagard RH, Cornelissen VA. Incidence of cardiovascular events in white-coat, masked and sustained hypertension versus true normotension: a meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2007;25:2193–2198.

- de la Sierra A, Banegas JR, Vinyoles E, et al. Prevalence of masked hypertension in untreated and treated patients with office blood pressure below 130/80 mm Hg. Circulation. 2018;137:2651–2653.

- Banegas JR, Ruilope LM, Williams B. White-coat uncontrolled hypertension, masked uncontrolled hypertension, and true uncontrolled hypertension, phonetic and mnemonic terms for treated hypertension phenotypes. J Hypertens. 2018;36:446–447.

- Giner V, Esteban MJ, Ragheb A, et al. Short-term implications related to antihypertensive drugs. Reference to MEDIDA and HYVET studies. Med Clin (Barc). 2010;134:657–659.

- Galvan VG, Giner MJE. Strategies for screening of secondary high blood pressure. Hipertensión (Madr). 2016;23:284–297.

- Escobar C, Barrios V, Alonso FJ, et al. Working group of arterial hypertension of the Spanish Society of Primary Care Physicians; PRESCAP 2010 investigators. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1138–1145.

- Conthe P, Mata M, Orozco D, et al. Degree of control and delayed intensification of antihyperglycaemic treatment in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in primary care in Spain. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;91:108–114.

- Lavoie KL, Rash JA, Campbell TS. Changing provider behavior in the context of chronic disease management: focus on clinical inertia. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;57:263–283.

- Sánchez Chaparro MA, Calvo Bonacho E, González Quintela A, et al. ICARIA (Ibermutuamur CArdiovascular RIsk Asessment) Study Group. High cardiovascular risk in Spanish workers. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;21:231–236.

- Marcinkiewicz A, Plewka M, Hanke W, et al. Is it possible to improve compliance in hypertension and reduce therapeutic inertia of physicians by mandatory periodical examinations of workers? Kardiol Pol. 2018;76:554–559.

- McCormack T, Krause T, O'Flynn N. Management of hypertension in adults in primary care: NICE guideline. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:163–164.

- Agarwal R, Bills JE, Hecht TJ, et al. Role of home blood pressure monitoring in overcoming therapeutic inertia and improving hypertension control: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2011;57:29–38.

- Josiah Willock R, Miller JB, Mohyi M, et al. Therapeutic Inertia and treatment Intensification. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20:4.

- Liu H, Wang H. Early detection system of vascular disease and its application prospect. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1723485

- Ram CV. Hypertension guidelines: good-bye to confusion and welcome to clarity. Indian Heart J. 2015;67:18–22.

- Kronish IM, Moise N, McGinn T, et al. An electronic adherence measurement intervention to reduce clinical inertia in the treatment of uncontrolled hypertension: The MATCH cluster randomized clinical trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:1294–1300.

- Milani RV, Bober RM, Milani AR. Hypertension management in the digital era. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2017;32:373–380.

- Santschi V, Chiolero A, Colosimo AL, et al. Improving blood pressure control through pharmacist interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000718.

- Rodilla E, Adell M, Giner V, et al. Arterial stiffness in normotensive and hypertensive subjects: frequency in community pharmacies. RIVALFAR study group. Med Clin (Barc) 2017;149:469–476.

- Wood PW, Boulanger P, Padwal RS. Home blood pressure telemonitoring: rationale for use, required elements, and barriers to implementation in canada. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33:619–625.

- Crowley MJ, Smith VA, Olsen MK, et al. Treatment intensification in a hypertension telemanagement trial: clinical inertia or good clinical judgment? Hypertension. 2011;58:552–558.