Abstract

Purpose: To study the differences in attitudes towards hypertension and drug treatment between patients persistent and non-persistent to antihypertensive drug treatment.

Materials and methods: Cross-sectional study on patients with hypertension treated at 25 primary healthcare centres in Stockholm, Sweden. Questionnaires were sent to the patients 3–12 months after initiation of antihypertensive drug treatment. Persistent medication users, defined as patients with less than 30 days without tablet supply between prescription refills, were compared with non-persistent users by scores from Likert scales: Brief-Illness Perception Questionnaire (Brief IPQ, 0–10) and Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ General, 4–20 and BMQ Specific, 5–25).

Results: A total of 711 patients were included in the final analyses (mean age: 62 years; 50% women), of whom 609 (86%) were classified as persistent and 102 (14%) as non-persistent by analyses of their filled prescriptions. Likert scales from the Brief-IPQ showed (all p < 0.02) that persistent patients believed that hypertension was a chronic condition (median 6 vs. 4), that hypertension had less consequences on their life (median 2 vs. 3) and that they can prevent cardiovascular disease by taking antihypertensive treatment (median 7 vs. 5). Likert scales from the BMQ General showed (all p < 0.02) that persistent patients believed that there are potential benefits from taking the treatment (median 16 vs. 16), and they did not believe that the doctors put too much trust in drugs (median 12 vs. 13). Further, results from the BMQ Specific showed that they believed that the antihypertensive drugs are necessary for them in order to maintain or improve their own health (median 17 vs. 16).

Conclusions: Primary healthcare providers should further emphasize the chronicity of hypertension diagnosis and the benefits of treatment, to improve the patients’ medication persistence to antihypertensive treatment.

Introduction

Hypertension is one major cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The Global Burden of Disease project reported in 2012 that an elevated systolic blood pressure above 115 mm Hg is the largest contributing factor to global burden of disease and mortality [Citation1]. Thus, blood pressure levels in patients with hypertension need to be controlled. There are several antihypertensive drugs available on the market, all of which have proven to reduce blood pressure and decrease the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [Citation2]. However, although blood pressure control has improved greatly over the last decade, observational studies from Sweden and other countries still show that hypertensive patients do not reach target blood pressure [Citation3–7], and the benefits demonstrated in randomized clinical trials are therefore not appreciated in clinical practice. Although there may be several explanations behind poor blood pressure control, poor medication-taking behaviour is believed to be a major contributing factor.

Patients who are not taking prescribed drugs may be doing so unintentionally or intentionally. Prior studies on patient characteristics related to poor persistence to antihypertensive therapy often conclude that male sex, low age, moderately elevated systolic blood pressure at initiation of antihypertensive treatment and foreign country of birth are important predictors [Citation8–10]. Studies also show that many patients discontinue their antihypertensive treatment early after initiation of antihypertensive therapy [Citation8,Citation11]. Adherence measures how well the patient takes their medication, while medication persistence measures for how long the patient takes their medication [Citation12]. It is important to separate these terms as they measure different things. Patients’ attitudes towards disease (ie hypertension) and treatment (ie drugs) have been studied in relation to poor medication-taking behaviour, but only in relation to medication adherence (not persistence), and usually with too small study populations and poor statistical power.

In the current study, we focused on medication persistence, and we applied the best method for studying patients’ attitudes in a larger population, which is through questionnaires. Two questionnaires commonly used for this purpose are the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (Brief-IPQ) and Beliefs about Medicines questionnaire (BMQ) [Citation13,Citation14]. Some studies have assessed attitudes in relation to hypertension or medication-taking behaviour, but they have either been too small, focused on secondary prevention, or assessed medication-taking behaviour through a self-reporting [Citation15–23] rather than to use a more objective way of measuring medication-taking behaviour, such as pharmacy claims data. Further, some studies addressed an elderly population only, did not include patients newly initiated on antihypertensive treatment, or did not restrict their inclusion to patients with a confirmed diagnosis of hypertension [Citation15–18,Citation20–23]. The question remains if those results can be applied also to a healthier population, such as patients newly initiated on antihypertensive treatment in primary healthcare. Furthermore, it is less clear to what extent beliefs and attitudes towards hypertension and antihypertensive drugs differ between patients who continue to take their antihypertensive treatment and those who discontinue their treatment.

Longitudinal analyses of pharmacy claims data have been suggested as the gold standard in analyses of persistence [Citation24]. Registers may offer complete follow-up. However, they generally contain limited clinical data and lack information about the patient perspective. Thus, linking self-reported questionnaires with medical records and registry data may provide new knowledge on drug utilization patterns in patients with hypertension. The aim of this study was to assess potential differences in attitudes towards hypertension and antihypertensive medication among patients persistent and non-persistent to antihypertensive therapy.

Methods

Patients and setting

This cross-sectional study included patients 30 years or older, consulting primary healthcare, having a diagnosis of essential hypertension (ICD-10 code I10), and being newly initiated on antihypertensive drug treatment. Newly initiated on treatment were all patients who had not dispensed an antihypertensive therapy before January 1, 2015, as calculated from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, which includes all filled prescriptions all Swedish citizens has made since July 2005 [Citation25]. All primary healthcare centres in the South-western and North-eastern greater Stockholm, Sweden, representing different sociodemographic compositions, were invited to participate. All participating primary health care centers followed established national standards concerning ascertainment of diagnoses and registrations.

Information about patient characteristics was retrieved from the computerized electronic health records used by all participating centers (TakeCare, CompuGroup Medical Sweden AB, Uppsala, Sweden) and the study questionnaire. The data from the electronic health records was extracted by dedicated software [Citation26,Citation27]. Information collected included age, sex, native Swede (if the patients were born in Sweden or not), last recorded blood pressure prior to initiation of therapy, and cardiovascular comorbidity. Cardiovascular comorbidity was defined as a diagnosis of (with corresponding ICD-10 codes) atrial fibrillation/flutter (I48), congestive heart failure (I50), ischemic heart disease (I20-25), previous stroke/transient ischemic attack (I60-69, G45)), or diabetes mellitus (E10-11), as documented in the medical records until the date of the first prescription of any antihypertensive medication. Antihypertensive treatment (with corresponding anatomic therapeutic chemical classification system (ATC) codes) studied were angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (C09A and C09B), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB; C09C and C09D), beta receptor blockers (C07), calcium channel blockers (CCB; C08 and CO7FB02), and diuretics (C03A, C03B, C03D, C03E, C09BA, C09DA). Data on prescribed medication were retrieved from the electronic health records, while data on filled prescriptions were collected from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register [Citation24], and linked using each patient’s personal identification number [Citation28].

Questionnaires

Data on patients’ beliefs about hypertension, medication and self-reported medication persistence were collected through two validated questionnaires, with a total of 30 questions. In addition, six questions regarding sex, native Swede (yes/no), if patients had blood pressure monitor at home (yes/no), if patients had a blood pressure lowering drug for their hypertension (yes/no) and a three alternative question on the patient’s own self-assessment of persistence to treatment, were also included. The Brief-IPQ [Citation13] studies patients’ attitudes towards their disease by eight questions (). Each question represents a single item and one dimension of illness perception: consequences, timeline, personal control, treatment control, identity, concern, coherence, and emotional representation. Each question is rated on a Likert scale from 0 to 10. The BMQ [Citation14] aims at studying patient’s attitudes towards medicines, and is divided into two parts. The BMQ-General focuses on attitudes towards medicines in general and contains three subscales (harm, overuse, and benefit) with four questions each (). The BMQ-Specific contains questions about the specific prescribed and contains the subscales necessity and concern, with five questions each. This gives the BMQ a total of 22 questions scored on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). For individuals missing less than 60% of the answers, a mean value was calculated from the retrieved answers; otherwise the corresponding subscale was excluded. The Swedish translation of the BMQ questionnaire was initially made for a study on secondary prevention in stroke [Citation20], and for the purpose of this study we modified the questions to be specific for hypertension.

Table 1. Overview of the items assessing attitudes towards hypertension in the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (Brief-IPQ).

Table 2. Overview of the various subscales assessing attitudes towards medicines from the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ).

Sampling procedure for the questionnaires

Eligible patients were identified from the electronic health record in each participating primary healthcare centre. The questionnaires were signed by the chief physician of each primary healthcare center and distributed to the patients by a company conducting patient surveys (Indikator, Institutet för kvalitetsindikatorer AB, Gothenburg, Sweden) between 3 and 12 months after the patients were prescribed their first antihypertensive drug. The patients could reply to the questionnaires by regular mail or by using the internet. Reminders were sent after two and four weeks, respectively. The completed questionnaires and data from the electronic health records were linked with data from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register at the National Board of Health and Welfare, and were then anonymized.

Calculations of medication persistence

Medication persistence was measured by means of the dosage text recorded in the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register and obtained for this study. We manually read a sample of all dosage text and developed algorithms in SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) for automatic extraction from the text in order to calculate tablet days covered. The method of calculation has been described previously [Citation8]. If a new prescription was filled before the end of supply of the previous filled prescription, the remaining tablets were accumulated to the latter one. Patients were classified as non-persistent if they had a gap of more than 30 days between end of dispensed supply and next dispensed prescription.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as proportions with 95% confidence intervals (CI) or as median values and interquartiles, as appropriate. Proportions between groups were evaluated by the Chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test, as appropriate, and the Mann Whitney U-test evaluated group differences. Variables included in multivariable analyses assessing differences between persistent and non-persistent patients were sex, age, blood pressure recorded before first prescription of antihypertensive treatment, diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular comorbidity (including atrial fibrillation, cerebrovascular disease, heart failure, ischemic heart disease). The internal consistency within each BMQ subscale was measured with Cronbach’s alpha (). A value between 0.7–0.9 is recommended [Citation29], and indicates a high correlation between the different questions measured in each subscale. Persistence was calculated by Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, determining the time of discontinuation for each patient. A two-tailed probability value (P) less than 0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

A power-calculation of the number of questionnaires needed was conducted before the study. To detect a difference of 0.2 in BMQ between persistent and non-persistent antihypertensive medication users with 80% power, a proportion of 80% persistent and a significance level of 0.05, a standard deviation of 0.7, and a 50% response rate, a total of 900 patients needed to be sent a questionnaire. A difference of 0.2 has been considered to be clinically relevant.[Citation20]

Ethical considerations

The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm approved the study (2015/589-31/4), and written consent from all primary health care centres was obtained. Patients consented to participate in the study by responding to the questionnaire, and approved of including the use of their clinical records in the analyses. All data were anonymized after linkage with the medical records, with no possibility to identify individual patients.

Results

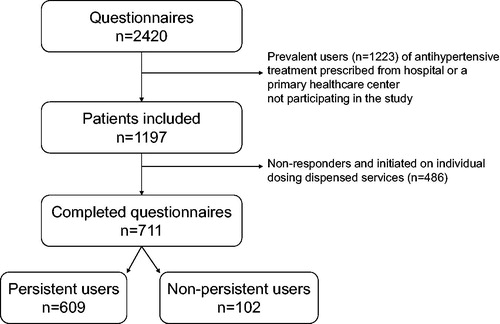

Out of 69 primary healthcare centres invited, 25 agreed to participate (see ) and through information from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, we identified 1197 eligible patients. A total of 711 (59%) responded to the questionnaire (mean age 62 ± 12 years, 50% women), and 609 (86%) of them were classified as persistent, and 102 (14%) as non-persistent. Patients responding to the questionnaire were more often 65 years or older, as compared to non-responders (44% vs. 28%, p < 0.01) and persistent to the antihypertensive medication (86% vs. 74%, p < 0.01). No sex differences were observed between responders and non-responders.

Of the 711 patient that responded to the questionnaire 21 (3%) did not report treatment with antihypertensive medication.

Patient characteristics in persistent and non-persistent medication users are presented in . A majority (59%) were 65 years or older, and 7% were 80 years or older. Diabetes and cardiovascular comorbidity were present in 7% and 5%, respectively. Approximately two thirds (69%) of all patients reported that they were born in Sweden, while 29% stated they were not, and for 2% data on country of birth was missing.

Table 3. Patient characteristics in persistent and non-persistent users of antihypertensive medication.

Mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures in the total study population prior to initiation of drug therapy were 160 ± 18 and 93 ± 12 mm Hg, respectively. Patients persistent to medical treatment had a higher systolic blood pressure compared to those non-persistent (161 ± 18 vs. 156 ± 17 mm Hg, p = 0.02). Three out of five patients reported that they used a home blood pressure monitor.

The antihypertensive drug classes dispensed at initiation of therapy were angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors were 44% (n = 316), calcium channel blockers 23% (n = 160), angiotensin receptor blockers 17% (n = 117), beta blockers, 7% (n = 48) and diuretics 2% (n = 11). A total of 3% (n = 18) received fixed combination therapy and 6% (n = 41) more than one antihypertensive drug class. Almost one third (n = 219) of all patients claimed that they had experienced side effects from their antihypertensive treatment (30% among persistent and 36% among non-persistent medication users, p = 0.21). The persistent and non-persistent users had a similar average number of different types of prescriptions per person (9.5 vs. 9.4).

There were large variations in attitudes towards hypertension between individual patients, but small differences between persistent and non-persistent medication users (). The Brief-IPQ ratings for “consequences” (How much does your hypertension affect your life?), were lower and “timeline” (“How long do you think your hypertension will continue?”) and “treatment control” (How much do you think your treatment can help your hypertension?) were higher in persistent than in non-persistent medication users.

Table 4. Brief-Illness Perception Questionnaire (Brief-IPQ) terms in persistent and non-persistent medication users of antihypertensive treatment.

Also results from the BMQ subscales showed large variations between individual patients in attitudes to antihypertensive medication (). Small significant differences between persistent and non-persistent patients were observed for the subscales Overuse and Benefit from the BMQ-General, and for the subscales Necessity and Concern from the BMQ-Specific, indicating that the persistent patients were more positive towards drugs in general and the specific antihypertensive drugs for which they had been prescribed.

Table 5. Comparisons of outcomes in the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ) between persistent and non-persistent patients.

Discussion

There are three major results of the present study. First, the findings suggest that persistent and non-persistent medication users differ in their beliefs about hypertension being a chronic disease. Second, compared to non-persistent patients, persistent medication users to a less extent believe that hypertensive disease has consequences to their life. Third, persistent patients consider antihypertensive medication to protect from future cardiovascular disease to a greater extent than do non-persistent patients.

First, persistent medication users believe to a greater extent than non-persistent patients that hypertension is a chronic disease. This finding has not been described previously, but results from a study in a secondary care hypertension clinic found that most patients with hypertension believe that it is a chronic condition [Citation30]. Our results suggest that the non-persistent patients would benefit from becoming aware that hypertension is a chronic condition with life-long treatment. Consequently, primary healthcare physicians and other health professionals need to emphasize this notion when initiating treatment.

Second, persistent medication users to a less extent believe that hypertensive disease has consequences to their life, as compared to non-persistent patients. Our findings are novel as no study appears to have addressed this issue previously. However, studies assessing the relation between the single Brief-IPQ item “Consequences” and medication adherence, did not find the adherence to be a large contributing factor [Citation16,Citation18], and we do not know if these results can be applied to our study on hypertensive patients in primary care, and if findings on medication adherence are comparable to those on medication persistence. A study comparing the impact of consequences on persistent compare to non-persistent patients would be needed to further analyze this issue.

Third, persistent patients consider antihypertensive medication to protect from future cardiovascular disease to a greater extent than do non-persistent patients. This is consistent with findings in post stroke patients [Citation20]. Thus, physicians in primary healthcare initiating antihypertensive treatment are recommended to acknowledge the benefits of antihypertensive drug treatment to their patients to improve medication persistence.

Our findings from the BMQ show that persistent patients have an overall more positive attitude towards medication, in particular antihypertensive medications, as compared to non-persistent patients. Persistent patients are also less concerned about the effects of antihypertensive drugs. These findings are expected and consistent with other studies assessing differences in BMQ between adherent and non-adherent patients [Citation17,Citation18,Citation20], and suggest that patients who begin antihypertensive medication should be informed of the benefits with treatment.

One sixth of all patients discontinued treatment before they responded to the survey. This corresponds to the findings in our previous study, where many patients discontinued treatment early after initiation [Citation8]. That study on patients initiated on antihypertensive treatment in primary care 2006–2007 found that angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors were the most commonly dispensed drugs class. Furthermore, the major determinants of discontinuation of drug treatment in that study were male sex, young age, only mild-to-moderate systolic blood pressure elevation, low income, and foreign country of birth, while educational level did not influence discontinuation rate [Citation8]. These patterns seem to remain a decade later. However, we do not have information on socioeconomic data available in the current study. Providers of primary healthcare should organize their services to offer patients at high risk for drug discontinuation greater attention.

One out of three patients claimed that they experienced side effects from their antihypertensive drug treatment. This is half of what was found in an observational study from Canada, were 62% reported that they experienced side effects from treatment [Citation31]. However, it is likely that only a limited number of discontinuations are explained by side effects. In a systematic review of clinical trials on oral antihypertensive agents in patients with essential hypertension the highest frequency of discontinuations due to diagnostic adverse events occurred with calcium channel blockers (6.7%) and alpha-blockers (6.0%); the lowest with diuretics and angiotensin receptor blockers (each 3.1%).

The main strengths of this study are that we studied a large unselected primary care population of patients with hypertension, representing two different socioeconomic districts of Stockholm, Sweden. We included the linkage of information from several sources, including electronic health records and the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register to the survey results, to calculate a suggested gold standard of persistence. In contrast to many previous studies [Citation15–18,Citation20–23], we used individual level pharmacy dispensing data to calculate medication-taking behavior. This may be considered the best data source available for studying drug utilization patterns in patients as it includes all dispensed prescription drugs regardless of reimbursement status.

This study also has important limitations. First, although calculating medication persistence from pharmacy claims data is a more objective method than self-assessment, the methods have to be adapted to the context in each country due to different data sources. Drug analyses in blood or urine are other objective methods to calculate medication persistence. However, there are limitations with those methods as they require more time, have costs, and may not actually measure real life medication persistence, since the patient would (for ethical reasons) have to be informed about the sampling beforehand. This would probably affect the medication persistence. Second, there are potential biases with questionnaires as data source, including non-response bias, response bias, and selection bias. Non-response bias would have occurred if some people did not respond to the questionnaire and they differ from the responders in terms of sociodemographic, behavior, or attitudes. This study was liable to non-response bias because not all who received the questionnaire responded. We found responders somewhat older and more persistent than non-responders, and the non-persistent patients answered the questionnaires to a lesser degree. However, we believe that a relatively good response rate (61%) provides a high potential of generalizability. We do not consider response bias a problem in this study, since only attitudes towards diagnosis and drugs were asked. It could have been a problem if people were asked about taking their drugs, but that was handled by using data from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register. Furthermore, recall bias, which would imply that the persistent users would recall differently compared to non-persistent users is not considered likely in this study. We believe that attitudes towards diagnosis and drugs are questions more or less consistent over time. Finally, we do not consider selection bias a major problem, since we did not select patients, but included all primary health care centers willing to participate in the survey. Third, some of the significant differences in the individual Likert scales ( and ) were numerically small and it may be questioned whether this represents clinically relevant differences. However, the study included a sufficient number of participants according to an appropriate power analysis of the size of the study population performed beforehand. Our findings from the different items in the questionnaires were overall consistent. Moreover, similar small significant differences were also shown in a cross-sectional study investigating the association between attitudes and medication adherence on patients with a stroke [Citation20].

In conclusion, differences in attitudes towards hypertension and drugs in these overall healthy hypertensive patients suggest that providers of primary health care, where most patients with hypertension are recognized, may improve medication persistence to antihypertensive treatment by informing the patients about the chronicity of hypertension, and the benefit and need of antihypertensive medication in preventing future cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgements

We thank Maria Sjölander, PhD, Umeå University, for expert feedback on the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2224–2260.

- Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension: 4. Effects of various classes of antihypertensive drugs–overview and meta-analyses. J Hypertens. 2015;33:195–211.

- Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:2043–2050.

- Godwin M, Williamson T, Khan S, et al. Prevalence and management of hypertension in primary care practices with electronic medical records: a report from the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network. CMAJ Open. 2015;3:E76–82.

- Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, et al. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;133:1–8.

- Chow CK, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA 2013;310:959–968.

- Wang J, Ning X, Yang L, et al. Trends of hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control in rural areas of northern China during 1991–2011. J Hum Hypertens. 2014;28:25–31.

- Qvarnström M, Kahan T, Kieler H, et al. Persistence to antihypertensive drug treatment in Swedish primary healthcare. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69:1955–1964.

- Friedman O, McAlister FA, Yun L, et al. Antihypertensive drug persistence and compliance among newly treated elderly hypertensives in Ontario. Am J Med. 2010;123:173–181.

- Ishisaka DY, Jukes T, Romanelli RJ, et al. Disparities in adherence to and persistence with antihypertensive regimens: an exploratory analysis from a community-based provider network. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2012;6:201–209.

- Corrao G, Zambon A, Parodi A, et al. Discontinuation of and changes in drug therapy for hypertension among newly-treated patients: a population-based study in Italy. J Hypertens. 2008;26:819–824.

- Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11:44–47.

- Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, et al. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:631–637.

- Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health. 1999;14:1–24.

- Jamous RM, Sweileh WM, El-Deen Abu Taha AS, et al. Beliefs about medicines and self-reported adherence among patients with chronic illness: a study in palestine. J Fam Med Primary Care. 2014;3:224–229.

- Lo SH, Chau JP, Woo J, et al. Adherence to antihypertensive medication in older adults with hypertension. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;31:296–303.

- Rajpura J, Nayak R. Medication adherence in a sample of elderly suffering from hypertension: evaluating the influence of illness perceptions, treatment beliefs, and illness burden. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20:58–65.

- Ross SD, Akhras KS, Zhang S, et al. Discontinuation of antihypertensive drugs due to adverse events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacotherapy 2001;21:940–953.

- Saarti S, Hajj A, Karam L, et al. Association between adherence, treatment satisfaction and illness perception in hypertensive patients. J Hum Hypertens. 2016;30:341–345.

- Sjölander M, Eriksson M, Glader EL. The association between patients' beliefs about medicines and adherence to drug treatment after stroke: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003551.

- Maguire LK, Hughes CM, McElnay JC. Exploring the impact of depressive symptoms and medication beliefs on medication adherence in hypertension–a primary care study. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:371–376.

- Chen SL, Tsai JC, Chou KR. Illness perceptions and adherence to therapeutic regimens among patients with hypertension: a structural modeling approach. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48:235–245.

- Hsiao CY, Chang C, Chen CD. An investigation on illness perception and adherence among hypertensive patients. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2012;28:442–447.

- Vrijens B, Heidbuchel H. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants: considerations on once- vs. twice-daily regimens and their potential impact on medication adherence. Europace. 2015;17:514–523.

- Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM, et al. The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register–opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidem Drug Safe. 2007;16:726–735.

- Hjerpe P, Merlo J, Ohlsson H, et al. Validity of registration of ICD codes and prescriptions in a research database in Swedish primary care: a cross-sectional study in Skaraborg primary care database. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2010;10.

- Kristianson KJ, Ljunggren H, Gustafsson LL. Data extraction from a semi-structured electronic medical record system for outpatients: a model to facilitate the access and use of data for quality control and research. Health Informatics J. 2009;15:305–319.

- Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, et al. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24:659–667.

- Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ Prim Care 2011;2:53–55.

- Ross S, Walker A, MacLeod MJ. Patient compliance in hypertension: role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18:607–613.

- Gregoire JP, Moisan J, Guibert R, et al. Determinants of discontinuation of new courses of antihypertensive medications. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:728–735.