Abstract

Purpose

Hypertension is the most important risk factor for disease and premature death. Treatment strategies adjusted for cardiovascular risk have been proposed in guidelines, but real-life treatment strategies for patients with newly diagnosed hypertension in Germany are largely unknown. The aim of the study was to analyse initial drug treatment strategies and associated risk status in patients with newly diagnosed hypertension.

Material and methods

In the representative research database of the public health insurance system in Germany (2077899 individuals) we identified patients with newly diagnosed hypertension in 2012 and analysed co-existing cardiovascular co-morbidities and hypertension-mediated organ damage by ICD-codes as qualifiers for high risk. Health insurance billing datasets for redeemed prescriptions were analysed at several time points using ATC-codes.

Results

The incidence of hypertension was 2.6%, 33.6% of the patients were at high risk at diagnosis, mainly due to cardiovascular co-morbidities. Most patients initially received monotherapy (55.4%), of which ACE inhibitors (43.8%) or beta-blockers (32.4%) were the leading drug classes, while 21.7% of patients received no drug therapy during the first year. The treatment strategies of low and high-risk patients resembled each other – high-risk patients also received mostly monotherapy during the first year after diagnosis (53.4%), while 13.7% remained without drug therapy. Combination therapy was the most frequent treatment strategy one year after hypertension diagnosis (40.6%) and in the long term (68.4%).

Conclusion

Initial treatment strategies may not always be stratified according to cardiovascular risk. The majority of patients with hypertension receives initial monotherapy independent of their individual risk. However, combination therapy represents the major form of therapy in the long-term.

Introduction

Arterial hypertension is the most important risk factor for cardiovascular disease and death. Sufficient control of blood pressure leads to a significant reduction of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [Citation1,Citation2]. In addition to lifestyle modification, several effective antihypertensive drug classes are available [Citation3,Citation4]. Nevertheless, hypertension control rates remain at an unsatisfactory level until today [Citation5].

The optimal therapeutic strategy after initial diagnosis of hypertension is currently under discussion. The 2007/2013 ESH guidelines proposed a therapeutic algorithm based on the overall cardiovascular risk. An initial combination therapy could be considered in patients with high cardiovascular risk or with markedly high blood pressure [Citation3,Citation4]. In the current guideline the therapy algorithm has been significantly simplified while therapy stratification according to cardiovascular risk has become less important. The 2018 ESH guidelines recommend an initial combination therapy for the majority of patients. Only hypertensive patients with mild hypertension and no other risk factors as well as frail and old hypertensive patients should receive an initial monotherapy [Citation6]. However, other societies still continue to favour a more complex risk-adapted approach [Citation7].

The recommendations proposed in guidelines are mostly based on the results of clinical trials and data sets which were acquired under controlled conditions. To what extent the recommendations are applied and implemented in everyday clinical practice is not known. The aim of the study was to describe and analyse initial drug treatment strategies in patients with newly diagnosed hypertension from a national database of reimbursement claims in Germany. Of particular interest was the question whether the presence of cardiovascular co-morbidities or hypertension-mediated organ damage, evidence of high risk, did influence initial treatment strategies as recommended in the 2007/2013 guidelines, i.e. whether a risk-adjusted treatment strategy was followed in real-life.

Methods

The analysis is based on data from the German research database for billing information of public health insurance companies, which is maintained by Arvato Health Analytics GmbH. This database contains pooled, anonymized accounting information from six statutory health insurance companies, which are representative of the national health insurance system in Germany [Citation8]. Arvato Health Analytics was responsible for data management and retrieval.

The analysis includes data from 2077899 individuals over 18 years of age from 2011–2013. All patients with a diagnosis of hypertension or hypertension-related disease (ICD I10-I15) in 2012 were considered. A patient was considered newly diagnosed if no such diagnosis was registered in the 2011 pre-observation period and considered existing hypertension when a diagnosis was registered in 2011 onwards. In addition, it was examined whether at least one of the following risk-relevant comorbidities has been coded: stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, diabetes, chronic renal failure or hypertensive end organ damage (ICD I11-15, I60-69, I21-22, I50, E10-14, N17-19). The presence of at least one of these diagnoses qualified the patient as high risk. On the basis of the health insurance accounting data, which are based on prescriptions redeemed in the pharmacy, the antihypertensive medication was examined after the initial diagnosis as well as during follow-up according to the ATC classification. The follow-up analyses are based on aggregated data, whereby the highest therapy class was counted in each case. All newly diagnosed patients were followed up for one year.

Results

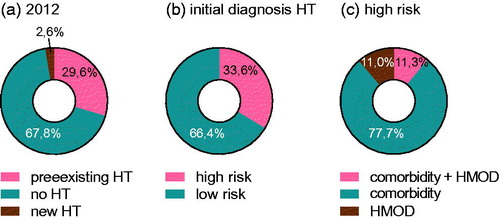

In total, datasets of 2077889 adult individuals from 2012 were analysed. In this representative cohort arterial hypertension occurred with an incidence of 2.6% and a prevalence of 32.2% (). At diagnosis, patients were on average 59 years old, with both sexes affected equally (50% each). In contrast, patients in the database with pre-existing hypertension were on average 66 years old.

Figure 1. Prevalence, incidence and risk distribution of patients with arterial hypertension. (a) Proportion of patients with known and newly diagnosed hypertension (HT) in 2012. (b) Patients with incident hypertension who were known to have one or more cardiovascular comorbidities (stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, chronic kidney disease or diabetes) or hypertension-mediated organ damage (HMOD) were classified as risk patients. (c) Percentage of risk patients with one or more HMOD only, cardiovascular comorbidities only, or both.

33.6% of patients with incident hypertension met the prespecified criteria for a risk constellation, since these individuals had co-existing hypertension-mediated organ damage (HMOD) and/or co-morbidities (), while the prevalence of risk constellation in patients with pre-existing hypertension was 44.9% (data not shown).

Risk-attribution analysis demonstrated that co-morbidities (stroke, heart attack, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, diabetes) accounted for 77.7% of the risk population, while HMOD accounted for 11.0% of risk, and HMOD plus co-morbidities accounted for 11.3% of risk patients ().

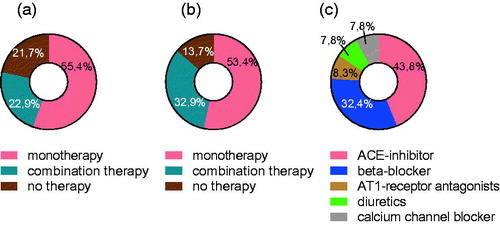

As initial treatment choice, 55.4% of patients received monotherapy, whereas 22.9% received antihypertensive combination therapy. In 21.7% of cases no therapy was initiated or redeemed within the first year after diagnosis (). Of note, the subgroup of risk patients also received monotherapy to almost the same extent as the general population (53.4%), while combination therapy was started in 32.9% of the cases. Furthermore, 13.7% of risk patients did not receive or redeem any prescribed antihypertensive therapy within the first year after diagnosis (). In the overall cohort, only minor differences between men and women with regard to the initial therapeutic strategy were observed. No therapy was recorded in 21.0% of female patients and 22.3% of males, monotherapy occurred in 57.8% of female patients and 53.1% in male patients and combination therapy was recorded in 21.2% of females and 24.6% in males.

Figure 2. Therapeutic strategies for patients with newly diagnosed HT. (a) Proportion of patients with initial monotherapy, combination therapy or no therapy (1 year). (b) Proportion of high-risk patients with initial monotherapy, combination therapy or no therapy. (c) Proportion of different antihypertensive drug classes in monotherapy.

The drug classes most frequently prescribed for monotherapy were ACE inhibitors (43.8%), beta-blockers (32.4%), AT1 receptor antagonists (8.3%), diuretics (7.8%) and calcium antagonists (7.8%) ().

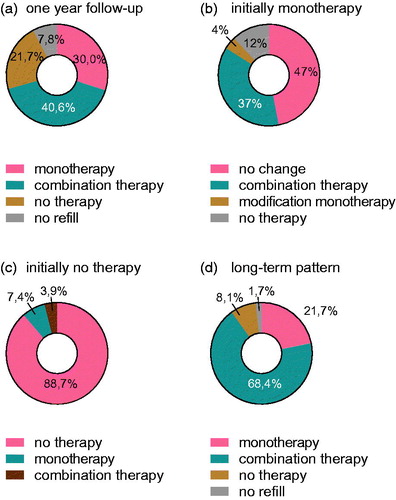

One year after diagnosis, combination therapy (41%) had replaced monotherapy (30%) as the major form of therapy, while a total of 29.5% of the patients were without drug therapy one year after diagnosis (21.7% no initiation/7.8% no re-fill) ().

Figure 3. HT treatment after one year and long term. (a) Therapeutic strategy one year after diagnosis. (b) Therapeutic strategy one year after diagnosis in patients with initial monotherapy. (c) Therapeutic pattern one year after diagnosis in patients without initial drug therapy. (d) Long-term (>1 year) therapy pattern in patients with pre-existing hypertension.

In patients with initial monotherapy, drug treatment was adjusted in 53% of all cases within the first year. In 37% of the cases the therapy was escalated to a combination therapy, 4% of the patients received another antihypertensive substance class and 12% of the patients stopped taking the medication ().

The majority of patients who did not receive initial drug therapy at diagnosis remained without therapy in the first year (88.7%), while only a small proportion adopted delayed monotherapy (7.4%) or combination therapy (3.9%) ().

In the long term, patients with pre-existing hypertension mostly received combination therapy (68%), while 21.7% of these patients were treated with monotherapy and 9.9% remained without drug therapy ().

Discussion

Arterial hypertension is an important cardiovascular risk factor with a worldwide prevalence of about 30–45% [Citation1,Citation2]. Sufficient blood pressure control is one of the most effective strategies to reduce cardiovascular disease burden [Citation5]. In line with the results of the study on the health of adults in Germany (DEGS1) [Citation9], hypertension occurred in this analysis with a prevalence of 32.2% and had an incidence of 2.6% (). Compared to systematic studies, the prevalence of HMOD in this cohort appears to be relatively low: HMOD was registered in 22.3% of patients at risk. If hypertensive patients are examined systematically by clinical parameters, the rate of HMOD can be high as 64% [Citation10]. This either suggests significant underdetection of HMOD, or underreporting in ICD-based HMOD data in every day clinical practice, which contributes to suboptimal risk-assessment or risk status communication.

After initial diagnosis, drug therapy was started in 78.3% of patients. In the long term 89.7% of patients receive antihypertensive medication (). These values are higher than the rate determined in the DEGS1 survey (71.6%) [Citation9]. This could be due to the fact that the billing data also included patients who are no longer able to participate in a survey due to increased morbidity or lack of mobility. The datasets are based on the number of redeemed prescriptions and should therefore reflect the real situation of the patient quite well. Secondary non-adherence as an important limiting factor of drug therapy cannot be conclusively assessed either from these data or from a survey. Nevertheless, it can be seen as a possible factor of interference.

The drug therapy pattern is subject to significant changes over time. Initially, monotherapy was established in the majority of cases (55.4%), while in the long-run combination therapy was prescribed in about two thirds of the cases (). The ESH/ESC guidelines of 2007 and 2013 already indicated that a large proportion of patients require combination therapy for sufficient blood pressure control [Citation3,Citation4]. A meta-analysis demonstrated that blood pressure control is higher with combination therapy than with a dose adjustment of the individual substance [Citation11]. In our analysis, 37% of patients with initial monotherapy were switched to combination therapy within the first year after diagnosis. After one year, combination therapy was the leading therapy strategy (41%). (). This rapid escalation could indicate early treatment failure, but might also be explained by progression of hypertension or progression of co-morbidities.

In the context of monotherapy, ACE inhibitors and beta blockers were used most frequently (). According to the 2007/2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines, both drug classes belonged to first-line therapy [Citation3,Citation4]. However, there is evidence that beta-blockers are inferior to other drug classes with regards to cardiovascular outcome [Citation1]. The current guidelines only propose their use if a specific indication is present [Citation6]. Follow-up studies should analyse whether altered guideline recommendations lead to a change in the prevalence of beta-blockers for the initial treatment of hypertension.

The initial treatment pattern of patients at risk was very similar to that of the overall collective: the majority of these patients initially received monotherapy (53.4%) and 32.9% received combination therapy. 13.7% of the patients remained without drug therapy. The 2007/2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines suggest starting combination therapy in patients with increased cardiovascular risk or severe hypertension [Citation3,Citation4]. Against this background, 67.1% of the patients received an initial therapy pattern more appropriate for a low risk constellation ().

This discrepancy between prescription data and guideline recommendations could be intended by physicians. Especially the strategic avoidance of polypharmacy in order to improve adherence could be seen as a possible explanatory approach. However, these results also suggest that initial therapy is not always stratified according to cardiovascular risk. This could be due to insufficient awareness of risk-adjusted treatment schemes or to problems in risk perception. The risk evaluation proposed by the former ESH/ESC Guidelines was based on cardiovascular diseases but also on a variety of cardiovascular risk factors and findings indicating (subclinical) organ damage [Citation3,Citation4]. The integration and classification of all these findings and diagnoses may be difficult in everyday clinical practice, especially in decentralised health care systems. The relatively low prevalence of HMOD in this cohort could point to further limitations of risk assessment in every day clinical practice.

The current 2018 ESH guidelines recommend combination therapy for the majority of patients, whereas risk adjustment is just of minor importance [Citation6]. Risk-adapted therapy algorithms seem to be insufficiently implemented in every day clinical practice in Germany. Simplified treatment recommendations – as proposed by the current ESH/ESC guidelines- may offer an opportunity to improve feasibility of guidelines and could improve blood pressure control or prognosis in everyday clinical practice. However, this needs to be proven in further studies.

The analysis of accounting data offers the possibility to analyse real life data from health care systems. However, this analysis has important limitations. As mentioned above, there might be significant under-detection or under-reporting of co-morbidities/HMOD based on ICD-codes, which in any case would indicate significant problems in patient risk assessment or risk status communication, but which could confound our analysis of risk-adjusted treatment. Furthermore, it is methodically impossible to discriminate whether a medication was not prescribed or a prescription was not redeemed. In a study with 75 589 patients, the prescribed prescriptions were compared with the redeemed prescriptions. For antihypertensives, primary non-adherence was high as 28.4% [Citation12]. Moreover, dose adjustments as a potential therapeutic strategy cannot be detected. As blood pressure readings are not reported, the quality of the blood pressure control in the examined cohort cannot be assessed. In a study conducted in the period 2008–2011, the rate of controlled hypertension in Germany under study conditions was 71.5% [Citation13].

Ethical approval

The research work follows the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, FP upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):957–967.

- Rapsomaniki E, Timmis A, George J, et al. Blood pressure and incidence of twelve cardiovascular diseases: Lifetime risks, healthy life-years lost, and age-specific associations in 1·25 million people. Lancet. 2014;383(9932):1899–1911.

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al.; Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology. 2013 ESH/ESC practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Blood Press. 2014;23(1):3–16.

- 2007 ESH‐ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Blood Press [Internet]. 2007;16(3):135–232.

- Chow CK, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. J Am Med Assoc. 2013;310(9):959.

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 Practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. Blood Press. 2018;27(6):314–340.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management NICE guideline [Internet]. 2019. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136

- Gesundheitsforen Leipzig GmbH (GFL) arvato health analytics G. Individuelle Analyselösungen und Versorgungsforschung im Gesundheitsmarkt [Internet]. Leipzig; 2016. [cited 2020 May 2]. Available from: https://www.gesundheitsforen.net/portal/media/gesundheitsforen/analytik/informationsbroschuere/Informationsbroschuere_Forschungsdatenbank.pdf

- Neuhauser H, Thamm M, Ellert U. Blutdruck in Deutschland 2008–2011Blood pressure in Germany 2008–2011. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforsch - Gesundheitsschutz. 2013.

- Papazafiropoulou A, Skliros E, Sotiropoulos A, et al. Prevalence of target organ damage in hypertensive subjects attending primary care: C.V.P.C. study (epidemiological cardio-vascular study in primary care). BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12(1):75.

- Wald DS, Law M, Morris JK, et al. Combination therapy versus monotherapy in reducing blood pressure: meta-analysis on 11,000 participants from 42 trials. Am J Med. 2009;122(3):290–300.

- Vogeli C, Weissman JS, Stedman MR, et al. Primary medication non-adherence: analysis of 195,930 electronic prescriptions. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(4):284–290.

- Sarganas G, Knopf H, Grams D, et al. Trends in antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control among adults with hypertension in Germany. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29(1):104–113.