Abstract

Purpose

Early treatment of hypertension is important to reduce adverse cardiovascular outcomes. The aim of this study was to investigate the time delay from detection of a high blood pressure in a health screening survey to hypertension diagnosis in primary care.

Materials and methods

Seventy years old inhabitants in the Uppsala County were randomly invited to the Prospective Investigation of the Vasculature in Uppsala Seniors (PIVUS) study. We found 409 individuals without antihypertensive treatment with a blood pressure >140/90 mmHg, being the average of three recordings measured after 30 min rest in a supine position. These individuals were recommended to ask their primary care physician to further investigate this finding.

Results

During 10 years of follow-up, 285 of them (70%) received a hypertension diagnosis. The mean time to diagnosis was 5 (SD 2) years. The chance of receiving a diagnosis of hypertension during the follow-up period in this group with elevated blood pressure at baseline was related to the systolic blood pressure (OR 1.04 per 1 mmHg, 95%CI 1.02–1.04), the BMI (OR 1.06 per 1 kg/m2, 95%CI 1.01–1.12), and statin use (OR 3.76, 95%CI 1.35–10.3) at the health survey, but was not significantly related to sex, prevalence of diabetes, or use of salicylic acid. No significant interaction between sex and systolic blood pressure regarding hypertension diagnosis was observed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, when an elevated blood pressure was discovered in elderly persons at a health screening, 70% of those received a hypertension diagnosis within 10 years, with a mean time to diagnosis of 5 years. Health care actions should be enforced to shorten this time lag both in terms of information to the individuals, as well as the handling of this patient group in primary care.

Keywords:

Introduction

Hypertension is one of the major risk factors for cardiovascular disease [Citation1]. Blood pressure lowering significantly reduces the risk of major cardiovascular disease events, such as coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, as well as all-cause mortality [Citation2–4].

This risk reduction is proportional across various population subgroups, irrespective of starting blood pressure [Citation3,Citation5]. Prevalence of hypertension in Sweden is about 27%, but only 20–30% of those who are prescribed antihypertensive medicine reach target blood pressure levels [Citation6].

Several studies have highlighted the poor adherence to blood pressure-lowering treatment [Citation7] but the average time between discovery of high blood pressure and the time of diagnosis is largely unknown. The aim of our study was to investigate the time delay from the discovery of a high blood pressure and the time to a hypertension diagnosis. To study this aim, we evaluated 409 persons participating in the community-based Prospective Investigation of Vasculature in Uppsala Seniors (PIVUS) study who were free from antihypertensive treatment but were found to have a blood pressure level ≥140/90 mmHg at the baseline examination. These subjects were told to ask their primary care physician to follow-up on this finding. We also investigated if some clinical characteristics were associated with the likelihood of receiving a hypertension diagnosis during the follow-up period. In addition, we have also investigated the risk of incident hypertension diagnosis over 10 years in the total sample free from hypertension at baseline. Furthermore, since a sex-difference regarding blood pressure control has been described [Citation8], we also investigated if we could find any sex-difference in the time delay from the discovery of a high blood pressure and the time of a hypertension diagnosis.

Methods

The PIVUS study

Eligible were all men and women aged 70 years residing in the County of Uppsala, Sweden. They were chosen from the register of county living and were invited in a randomised order from April 2001 to June 2004 by an invitation by letter within one month of their 70th birthday. Of 2025 invited persons, 1016 were investigated, giving a participation rate of 50.1% [Citation9].

The initial examination at age 70 has previously been described in detail [Citation9]. A second examination of participants was performed at the age of 75 years [Citation10]. All participants were investigated in the morning after an overnight fast. No medication or smoking was allowed after midnight. Blood pressure was measured in supine position by a calibrated mercury sphygmomanometer to nearest mm Hg after at least 30 min of rest and the average of three recordings was used. All persons with blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg were informed verbally and given written information to contact their primary health care physician for further follow up.

Follow-up and outcomes

We have in the Uppsala County Council a computerised system for medical records, being the same for primary care and hospital care. In these records, we search for different cardio-metabolic disease (including hypertension) 10 years after the baseline investigation in PIVUS study. The end-point used in this study was a diagnosis of primary hypertension (ICD-10, code I10.9). No diagnoses of secondary or renovascular hypertension were found. We have not evaluated if the diagnosis of primary hypertension was valid or not, but in all cases a blood pressure >140/90 mmHg was noted in the records at the time of diagnosis. An experienced physician (L.L.) performed the search of the records.

Statistical analysis

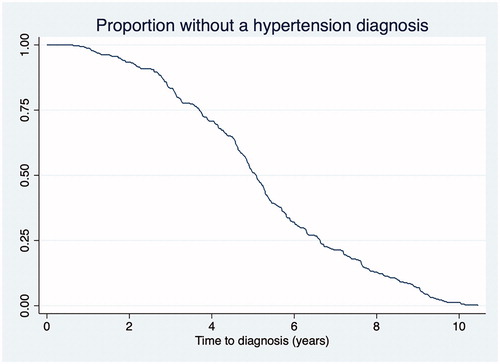

Logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate which baseline characteristics that were related to a hypertension diagnosis during 10 years follow-up in the total sample, as well as in those with untreated high blood pressure at baseline in the PIVUS study. A Kaplan-Meyer survival curve was used to illustrate the time to diagnosis. STATA16 (STAT Inc., College Station, TX, USA) was used for calculations.

Results

In the total sample, 699 individuals did not have hypertension diagnosis at baseline. Of those, 409 showed either systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mmHg. Of those, 331 showed isolated systolic hypertension (SBP > 140 and DBP < 90 mmHg). Only 5 individuals showed isolated diastolic hypertension (SBP < 140 and DBP ≥90 mmHg).

Of the 409 participants with a blood pressure >140/90 mmHg at the examination at age 70 without antihypertensive treatment, 285 (70%) received a diagnosis of hypertension during 10 years of follow-up. The basic characteristics in this group are shown in .

Table 1. Medians (range) or proportions of basic characteristics in the subjects with a blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg without antihypertensive treatment.

During the 10 years of follow-up in the total sample without hypertension diagnosis at baseline, 318 (45%) cases of incident hypertension occurred. Subjects with a discovered hypertension at the baseline investigation (blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg) showed a more than 4-fold increased risk of a diagnosis of hypertension during the follow-up (OR 4.26, 95% CI 3.313–5.53, p < 0.0001). For subjects with isolated systolic hypertension the risk was doubled (OR 2.00, 95% CI 1.58–2.51, p < 0.0001), while no significant increase was seen for those with isolated diastolic hypertension at baseline (OR 1.24, 95% CI 0.40–3.87, p = 0.71).

The chance of receiving a diagnosis of hypertension during the 10-year follow-up period in the 409 subjects without treatment, but with a blood pressure >140/90 mmHg at the examination at age 70, was associated with the following factors at the baseline examination at age 70; systolic blood pressure (OR 1.04 for a 1 mmHg change, 95%CI 1.02–1.04, p < 0.0001), body mass index (BMI) (OR 1.06 for 1 kg/m2 change, 95%CI 1.005–1.12, p = 0.032), and statin use (OR 3.76, 95%CI 1.35–10.3, p = 0.010), but was not significantly related to diabetes, sex or use of salicylic acid. No significant interaction between sex and systolic blood pressure were seen in this respect ().

Table 2. Odds ratio of receiving hypertension diagnosis (during 10 years follow-up) in relation to different risk factors at baseline, such as sex, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, body mass index, use of statins and salicylic acid. The odds ratios are given in relation to female sex, systolic blood pressure in mmHg and body mass index in mg/m2.

In the group with normal blood pressure at baseline, statin use (OR 2.09, 95% CI 1.05–4.09, p = 0.032 and BMI (OR 1.08, 95% CI 1.01–1.14, p = 0.024) were related to a future diagnosis of hypertension, while SBP was less important in this group (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.99–1.05, p = 0.070).

In 251(88%) of those 285 participants, we could find the exact date of diagnosis in the medical records. In the remaining 34 participants, the date of diagnosis was uncertain, but within the 10 years follow-up. The mean time from the examination at age 70 to date of hypertension diagnosis in these 251 individuals with an exact date of diagnosis was 5.0 (SD 2.0) years. Survival estimates for time to diagnosis is shown in .

Discussion

The most important finding of this study is that the mean time to receive hypertension diagnosis from the first discovery of a high blood pressure was long. In the 70% of individuals who showed an elevated blood pressure on a health screening and received a diagnosis of hypertension within 10 years, it took an average of 5 years to diagnosis of hypertension. The reason for this time delay could be due both to doctor’s delay and patient´s delay. Information to the participants in the PIVUS study about the importance of treatment of hypertension might have been interpreted differently by different subjects and some individuals may not have taken the information of a high blood pressure seriously despite that both oral and written information was given.

The chance of receiving a diagnosis of hypertension during the 10-years follow-up period was associated with systolic blood pressure at the baseline examination at age 70, a high BMI and use of statins. Although both subjects with previously unknown elevated both SBP and DBP as well as those with previously unknown isolated systolic hypertension were told to make contact with their general practitioner regarding these findings, chance of receiving a diagnosis of hypertension was almost double as high in those previously unknown elevated both SBP and DBP compared to those with previously unknown isolated systolic hypertension. Thus, it might be that an elevation of both SBP and DBP is treated more seriously than isolated systolic hypertension.

In our study, blood pressure was measured in supine position after 30 min rest. Measuring blood pressure in supine position is a tradition in Sweden and for logistic reasons we used a longer period of rest (30 min) than usually used in the clinical setting. Since blood pressure usually declines with resting, it is likely that the blood pressure measured in the present study was lower compared to a measurement in the clinic. Therefore, the number of subjects with unknown hypertension is possibly underestimated in the present sample.

Having other co-morbidities, like obesity and indication for statin use also increased the chance of hypertension diagnosis, but a diabetes diagnosis was not a factor associated with hypertension diagnosis, as might be expected.

Only 70% of all persons with a high blood pressure received a diagnosis during 10 years. A part of this is likely due to regression towards the mean with a lower blood pressure at a second examination performed in the primary care setting. Nevertheless, systolic blood pressure increases steadily over time and those with an elevated systolic blood pressure at the baseline examination are very likely to develop manifest hypertension in the following years [Citation11].

An excellent coverage of the care given by the primary care (and hospital care) in the Uppsala County Council is recorded in our medical record system. However, if a subject moves to another region this health information could not be further followed. Between age 70 and 80 such mobility is uncommon in Sweden, but it might be that single individuals amongst the 30% who did not receive a hypertension diagnosis within 10 years actually received such diagnosis in another region of Sweden or abroad. Thus, the calculation of 30% not obtaining a hypertension diagnosis might be slightly overestimated.

The strength of the present study is that a fairly large number of subjects with a high blood pressure not previously having a hypertension diagnosis were identified and could be followed over the 10 years. One weakness is that the exact date of hypertension diagnosis could not be found in 12% of individuals who received a hypertension diagnosis during the follow-up. In those cases, it was evident that the diagnosis was set before the date when the hypertensive state was commented in the medical records. Therefore, the time delay might be slightly overestimated, since that was based on the cases where an exact date was available (in 88%). Another weakness is that, we only studied elderly Caucasian Swedes, so the time delay to diagnosis might be different in other population samples.

One reason for not giving antihypertensive drug treatment to subjects is frailty. Unfortunately, this association could not be evaluated due to lack of information in this study. In the elderly, it is a possibility that a new diagnosis of hypertension was not registered if other more urgent diseases were the focus of the visit to the health care.

In conclusion, when an elevated blood pressure was discovered in elderly persons at a health screening, 70% of those received a hypertension diagnosis within 10 years, with a mean time to diagnosis of 5 years. Health care actions should be enforced to shorten this time lag both in terms of information to the individuals, as well as the handling of this patient group in primary care.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kannel WB. Blood pressure as a cardiovascular risk factor: prevention and treatment. JAMA. 1996;275(20):1571–1576.

- Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension: 4. Effects of various classes of antihypertensive drugs-overview and meta-analyses. J Hypertens. 2015;33(2):195–211.

- Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):957–967.

- Wright JT, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103–2116.

- Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension: 7. Effects of more vs. less intensive blood pressure lowering and different achieved blood pressure levels – updated overview and meta-analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2016;34(4):613–622.

- Moderately elevated blood pressure. A report from SBU, the Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care. J Intern Med Suppl. 1995;737:1–225.

- Qvarnström M, Kahan T, Kieler H, et al. Persistence to antihypertensive drug treatment in Swedish primary healthcare. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(11):1955–1964.

- Chu SH, Baek JW, Kim ES, et al. Gender differences in hypertension control among older korean adults: Korean social life, health, and aging project. J Prev Med Public Health. 2015;48(1):38–47.

- Lind L, Fors N, Hall J, et al. A comparison of three different methods to evaluate endothelium-dependent vasodilation in the elderly: the Prospective Investigation of the Vasculature in Uppsala Seniors (PIVUS) study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(11):2368–2375.

- The PIVUS study. [Internet] Available from: www.medsci.uu.se/pivus.

- Vasan RS, Larson MG, Leip EP, et al. Assessment of frequency of progression to hypertension in non-hypertensive participants in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort study. Lancet. 2001;358(9294):1682–1686.