The 2020 International Society of Hypertension (ISH) Global Hypertension Practice Guidelines [Citation1] were developed by the ISH Hypertension Guidelines Committee to be evidence-based and, in addition, (a) to be used globally; (b) to be fit for application in low-resource and high-resource settings by advising on both basic/essential and optimal standards; and (c) to be concise, simplified, and easy to use.

The ISH has a long tradition of issuing hypertension guidelines, either stand-alone or jointly with other organisations such as the World Health Organisation (WHO). The jointly written 1999 WHO/ISH hypertension guidelines were the source of inspiration for developing the first European Society of Hypertension (ESH) Guidelines issued as an ESH Scientific Newsletter [Citation2]. The first full guidelines from ESH were issued jointly with the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and published in the Journal of Hypertension. This publication was the most widely cited paper in the medical literature in 2003 and 2004 [Citation3]. In the United States the National High Blood Pressure Education Program (NHBPEP) was founded in 1972 and its subsidiary Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC) began issuing hypertension guidelines in 1977 and updated them regularly until the task was taken over in 2017 by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA), in partnership with several other professional societies [Citation4].

Modern hypertension guidelines are evidence-based in the sense that they recommend medical treatments that have been proven effective in lowering blood pressure and preventing cardiovascular disease outcomes and death in randomised controlled clinical trials and/or in well-designed observational studies with large patient populations. The evidence base for these guidelines is extensive, and guidelines typically include many hundreds of references. Their complexity and the extensive background literature on which they are based is overwhelming to most practicing physicians, and most guidelines have drawn criticisms for being impractical for everyday use. The 2020 ISH guidelines were designed to solve this problem by being concise, simplified, and easy to use for the busy practitioner [Citation1]. The most recent ESC/ESH practice guidelines were also simplified for similar reasons [Citation5].

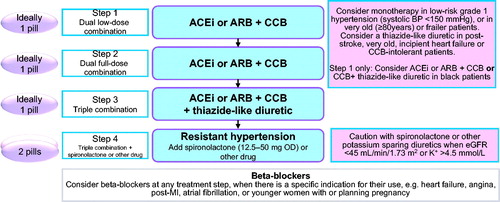

Since the various hypertension guidelines generally refer to the same clinical trials and observational studies as their evidence base, they might be expected to make similar treatment recommendations. However, there are differences between guidelines regarding important issues, e.g. the choice of first line treatment. The recommended treatment algorithm by ISH is shown in . Step 1 and step 2 include angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) plus calcium channel blockers (CCB) in low-dose and full-dose combination [Citation1]. The decision to move thiazide or thiazide-like diuretics such as chlorthalidone or indapamide to step 3 was based in part on results of the Avoiding Cardiovascular Events through Combination Therapy in Patients Living with Systolic Hypertension (ACCOMPLISH) trial [Citation6] in which the ACE inhibitor plus CCB combination prevented cardiovascular endpoints more effectively than the ACE inhibitor plus hydrochlorothiazide combination. The ACE inhibitor plus CCB combination was also the most effective combination in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT) when compared with the beta-adrenergic blocker atenolol plus bendroflumethiazide combination [Citation7].

Figure 1. Treatment Algorithm of the International Society of Hypertension. ACEi: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker; CCB: calcium channel blocker; OD: once a day; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; MI: myocardial infarction.

It is peculiar that in the ISH Guidelines only two outcome trials [Citation6,Citation7] performed in the Nordic countries, United Kingdom and the United States, provided the evidence base for the most important recommendation, choice of first line treatment, for hypertensive patients throughout the world. Numerous outcome trials in hypertension have shown the benefit of thiazide or thiazide-type diuretics in preventing cardiovascular disease outcomes. All placebo controlled trials of antihypertensive medications have shown that active treatment prevented cardiovascular disease outcomes, including stroke, heart failure, myocardial infarction, left ventricular hypertrophy and aortic aneurysm. Outcome trials that have compared diuretics with beta-blockers have shown no differences for the primary endpoints.

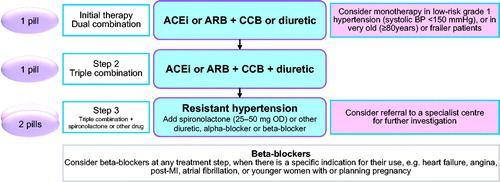

Further, numerous recent outcome trials have compared antihypertensive drugs of different classes head-to-head and have shown no inferiority when a diuretic was administered as the first or second line drug. The only outcome trial that has shown a difference between first line drugs for the primary endpoint is the Losartan Intervention for Endpoint prevention in hypertension study (LIFE). LIFE showed that losartan was superior to atenolol for the composite outcome of stroke, myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death, but hydrochlorothiazide was given to approximately 90% of study participants to ensure blood pressure control [Citation8]. Amlodipine was equally effective as valsartan in the Valsartan Long-term Use for endpoint Evaluation study (VALUE), but hydrochlorothiazide was given as the number 2 drug in both arms to ensure blood pressure control [Citation9]. Thus, many outcome trials of cardiovascular disease prevention in hypertension have included a diuretic as first or second step, clearly supporting the role of diuretics as a first line antihypertensive treatment, as recommended in the 2017 American [Citation4] and 2018 European [Citation5] hypertension guidelines ().

Figure 2. Treatment Algorithm of the European Society of Cardiology/ European Society of Hypertension. ACEi: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker; CCB: calcium channel blocker; OD: once a day; MI: myocardial infarction.

Importantly, several frequently occurring hypertension-related conditions including aging, obesity, diabetes and renal function impairment are associated with salt sensitivity, which favours diuretic treatment. Furthermore, insufficient diuretic treatment is one of the most frequent reasons of not achieving blood pressure targets. Finally, there is now increasing evidence that all diuretics are not equal in terms of efficacy and tolerability as well as clinical evidence [Citation10].

In conclusion, the ISH hypertension guidelines diverge from the American and European hypertension guidelines regarding choice of initial drug treatment. We are concerned that this could be a step in the wrong direction because a thiazide type diuretic, e.g. chlorthalidone or indapamide, is at top of the list of evidence-based first line antihypertensive drugs.

Disclosure statement

SEK, KN, MB and SO are editors of Blood Pressure and report no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose related to this editorial.

References

- Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. J Hypertens. 2020;38:952–1004.

- Kjeldsen SE, Erdine S, Farsang C, et al. 1999 WHO/ISH Hypertension Guidelines – highlights & ESH update. J Hypertens. 2002;20:153–155.

- Zanchetti A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, et al. 2003 European Society of Hypertension – European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1011–1053.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:1269–1324.

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. Blood Press. 2018;27:314–340.

- Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, et al. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2417–2428.

- Dahlöf B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, et al.; for the ASCOT Investigators. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:895–906.

- Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, et al.; for LIFE Study Group. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002;359:995–1003.

- Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Weber M, et al.; for the VALUE trial group. Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: the VALUE randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2022–2031.

- Burnier M, Bakris G, Williams B. Redefining diuretics use in hypertension: why select a thiazide-like diuretic? J Hypertens. 2019;37:1574–1586.