Abstract

Home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) is a convenient way to assess out-of-office blood pressure control and is recommended by numerous international guidelines to aid clinicians in the diagnosis and management of essential hypertension. Although available guidelines recommend the use of HBPM in patients receiving antihypertensive medication, their specific recommendations regarding optimal monitoring schedule, duration, and clinician interpretation of home blood pressure readings may differ among guidelines. Purpose: The purpose of this article is to review available international hypertension guideline recommendations related to the use of HBPM to improve hypertension control among patients receiving antihypertensive therapy. We also briefly highlight clinical trials that have shown improved blood pressure control using HBPM to intensify antihypertensive therapy and provide a practical guide for implementing HBPM to improve hypertension control. Results: Eleven international guidelines were identified and reviewed. In total, recommendations relating to which HBPM to use, number of measurements per day, and how to interpret home blood pressure values were largely in agreement among available guidelines. Conclusion: Clinicians recommending HBPM to their patients with hypertension should utilise a standardised HBPM protocol, based on available guideline recommendations.

Introduction

Hypertension, or elevated blood pressure (BP), is a leading modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease, stroke, and kidney disease [Citation1]. In the United States (US), the prevalence of hypertension varies from approximately 32 to 45% of adults, depending on BP thresholds used to define elevated BP [Citation2]. Despite effective and affordable antihypertensive medications, an estimated 28.7% of patients treated for hypertension have uncontrolled BP [Citation2]. Unfortunately, recent data suggest that BP control rates are declining among US adults with hypertension, while cardiovascular deaths related to hypertension are increasing [Citation3,Citation4].

Historically, decisions to initiate or intensify antihypertensive therapy have been based on office-measured BP values taken at clinician's office. Multiple factors can lead to inaccurate office-measured BP readings, including improper patient position, inappropriate BP measurement technique, and patient anxiety attributed to the healthcare setting [Citation5]. Given the potential for inaccurate office-measured BP and increased availability of home BP monitors, recent guidelines have advocated for the use of out-of-office BP monitoring to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension and to monitor treatment response in those taking antihypertensive therapy [Citation5–7]. Current options for out-of-office BP measurement include 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring and home BP monitoring (HBPM). HBPM has several advantages over office-measured BP, including a more reliable assessment of patients’ BP in their natural setting, multiple readings over several days, and has been shown to be more closely related to risks of developing hypertension end-organ damage and cardiovascular events compared to office-measured BP [Citation8]. Current hypertension guidelines recommend HBPM to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension, assess for white-coat or masked hypertension in patients not currently taking antihypertensive therapy, and evaluate BP control and medication adherence in those receiving antihypertensive treatment [Citation9].

Use of HBPM in clinical practice appears to be increasing as clinicians are increasingly recommending HBPM to their patients with elevated BP. In one survey, 96.8% of primary care clinicians reported using patient self-monitored BP readings and 98.5% reported making changes to medications based on patients’ home BP readings [Citation9]. Likewise, patients are open to HBPM also. A recent survey of patients with hypertension reported that 30.1% stated their physician had recommended HBPM [Citation10]. Among those recommended to use HBPM, 82% reportedly complied [Citation10]. While multiple international hypertension guidelines recommend HBPM for patients treated with antihypertensive medications [Citation5,Citation7,Citation11,Citation12], standardised clinical HBPM protocols for educating patients on appropriate use or recommended monitoring schedules are lacking. In a survey of primary care providers, nearly 97% of clinicians reported using HBPM in their patients; however, 99.5% of clinicians reported that HBPM patient education was done by a team member and not the clinician [Citation9]. Another survey examined the proportion of clinics with appropriate procedures for recommending HBPM based on current guidelines for out-of-office BP monitoring. Among the surveyed clinics, 48.8% utilised a non-clinician staff to provide HBPM training to patients, while only 27.6% reported a standardised policy for training patients on appropriate HBPM use [Citation9].

Given the increasing use of HBPM to manage hypertension, a consistent protocol for assessing and interpreting home BP readings is needed to ensure clinicians are following best practices. In this review, we compare recommendations from available international hypertension guidelines on clinical use of HBPM and interpreting home BP values to adjust antihypertensive medication. Additionally, we review monitoring schedules used in several clinical trials supporting HBPM to improve hypertension control, as well as provide a practical guide for implementing HBPM in clinical practice to improve BP control rates.

Recommendations for home blood pressure monitoring

A search for international hypertension guidelines providing specific recommendations for use of HBPM in patients treated for hypertension was conducted using PubMed. Guideline statements and consensus documents published from major hypertension management organisations within the last 10 years, and providing specific recommendations for HBPM and interpretation were included. Although the terms, ‘self-measured BP monitoring’ and ‘HBPM’ may seem interchangeable, HBPM specifically refers to BP measurement in ones’ home, but may be performed by someone other than the patient [Citation5]. Self-measured BP monitoring refers to BP measured by the individual, although it may occur outside of their home [Citation9]. For the remainder of this article, the term HBPM will be used as it is the term commonly used in available guidelines. A total of eleven international guidelines were identified and are summarised in .

Table 1. Recommendations for home blood pressure monitoring from International Hypertension Guidelines.

Recommendations for home BP monitoring devices

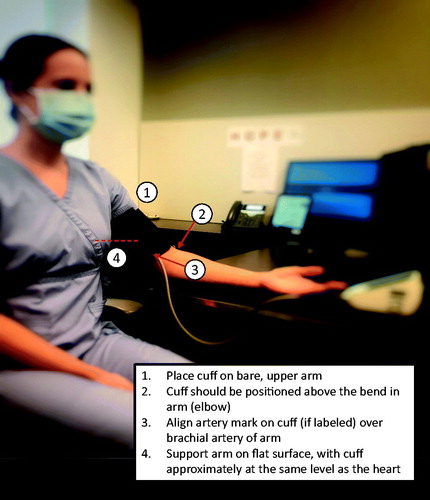

Reviewed guidelines favour the use of automated, oscillometric HBPM devices over the use of manual devices. Automated monitors with upper-arm cuffs assessing pressure of the brachial artery are consistently preferred over wrist or finger devices () when appropriate cuff sizes are available [Citation5,Citation6,Citation8,Citation11–17]. Wrist monitors are less reliable in comparison to upper arm cuffs due to incorrect positioning in relation to the heart and measurement of BP in both the radial and ulnar arteries, but may be considered in patients who are unable to obtain an appropriately sized upper-arm cuff [Citation8]. All eleven reviewed guidelines recommend using a validated HBPM for assessing BP control, yet only five cite resources for choosing a validated monitor [Citation6,Citation8,Citation14–16] (). Home BP monitors should also be routinely calibrated, and guidelines recommend clinicians compare office-measured BP against patients’ home device before initiation HBPM and periodically thereafter [Citation5,Citation12–15,Citation17]. Patients should receive education regarding appropriate HBPM use, and clinicians should assess patients’ technique before initiation HBPM, and periodically thereafter [Citation5,Citation12,Citation14,Citation15].

Table 2. Available resources for choosing validated home blood pressure monitors.

Recommendations for optimal BP monitoring schedule

Available guidelines provide specific instructions for the number of BP measurements per day and frequency of monitoring for appropriate assessment. All guidelines agree upon testing BP twice daily (in the morning and evening), with two consecutive measurements taken 1–2 min apart each time. Prior to each measurement, patients should be resting for at least 5-minutes and positioned correctly (). Reviewed guidelines offer varying recommendations regarding conditions prior to taking BP measurements, such as before or after meals and time since waking in the morning, yet most agree that morning BP measurements should be taken after emptying one’s bladder and before typical morning activities (caffeine, exercise, smoking). Four guidelines recommend assessing BP before the morning meal [Citation11–13,Citation16], and nine guidelines specify morning BP readings be taken before administering antihypertensive medications [Citation5,Citation6,Citation8,Citation11–13,Citation15–17]. Recommendations for evening BP readings are less consistent regarding timing in relation to meals. Three guidelines recommend measuring evening BP before the evening meal [Citation8,Citation16,Citation17], two guidelines recommend measuring after the evening meal [Citation11,Citation15], and three guidelines call for measuring BP before bed [Citation5,Citation12,Citation13]. Considering some patients may be taking antihypertensive medications more than once per day, two guidelines specify that evening BP measurements be taken before administering evening antihypertensive medications [Citation11,Citation16].

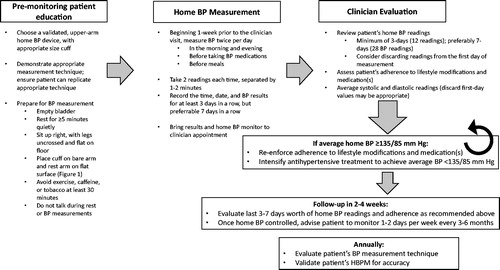

Figure 2. Recommended clinical approach to implementing home blood pressure monitoring to improve hypertension control.

The duration of HBPM assessment varies slightly between the reviewed guidelines; however, it is acknowledged that longer periods of continuous assessment provide superior data for managing hypertension. Consecutive measurements taken over a 3-day and ideally 7-day period are recommended to assess BP control. Excluding BP measurements taken the first-day is recommended by most guidelines, given expected higher values on the first day of evaluation. Once BP control is achieved, recommendations for continued HBPM measurement are mixed, ranging from weekly to biannually [Citation6,Citation8,Citation11,Citation13–16]. Time frames to reassess control of hypertension with HBPM should be determined based on patient-specific factors such as medication adherence, cardiovascular risk, comorbid conditions, age, and potential for labile BP. Providers should be mindful of ‘monitoring-fatigue’ when patients are asked to continuously monitor home BP despite controlled BP.

Evaluating home BP to guide treatment intensification

In patients treated with antihypertensive medications, assessing BP control with HBPM requires patients to measure BP over a minimum 3-day period, preferably a consecutive 7-day period, beginning 1-week prior to their next clinic visit. To assess BP control, guidelines recommend averaging all systolic and diastolic values taken during the 3 to 7-day measurement period (excluding readings on day 1). Two guidelines recommend averaging morning and evening values separately [Citation12,Citation13]. If the calculated average home BP is 135/85 mmHg or higher, equivalent to an office-measured BP of 140/90 mmHg, guidelines unanimously recommend intensifying antihypertensive therapy. Specific home BP goals are not recommended by most guidelines, although two guidelines offer specific home BP goals. The HOPE Asia Network recommends home BP goal of <135/85 mmHg for patients under 80 years, home BP of <145/85 mmHg for patients above age 80, and a systolic BP (SBP) goal of <125 mmHg for patients at increased cardiovascular risk, such as those with diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or cardiovascular disease [Citation12]. The 2020 Taiwan Hypertension Society considers home BP to be ‘well-controlled’ if both the morning and evening average BP values are <135/85 mmHg [Citation13]. Further, patients with hypertension-related organ damage are recommended to achieve a home BP of <130/80 mmHg [Citation13]. Time frames for reassessing home BP following adjustment of antihypertensive medications is provided in two guidelines. Recommendations from Australian guidelines[Citation16] call for reassessing home BP values approximately 4-weeks after medication adjustment, while guidelines from Taiwan[Citation13] recommend re-evaluating home BP control after 2 weeks.

Home blood pressure monitoring schedules from clinical trials

Multiple studies have evaluated changes in BP when HBPM is combined with additional management compared to usual care. A brief review of several of those trials, including how HBPM data was used to guide hypertension treatment, is described below.

A randomised trial compared HBPM with pharmacist management to usual care among patients with uncontrolled BP [Citation13]. Patients randomised to the HBPM group received a HBPM home and advised to check home BP 3-times per week and upload their results weekly to a web-based application which calculated weekly averages. These results were reviewed by clinical pharmacists, who contacted patients to assess medication adherence and if needed, intensify antihypertensive therapy. The proportion of patients with controlled BP at 6-months was greater in the HBPM group compared to usual care (). Additionally, patient reported satisfaction with hypertension care was also greater in the HBPM group versus usual care.

Table 3. Home blood pressure monitoring schedules and outcomes from select clinical trials.

A randomised cluster trial evaluated hypertension control rates among patients receiving HBPM with pharmacist-management compared to usual care over an 18-month period [Citation18]. Patients in the HBPM cohort were asked to submit at least six BP readings per week, preferably 3 readings taken in the morning and 3 readings in the evening. Pharmacist follow-up with HBPM patients occurred every 2 weeks until their home BP was controlled. Instead of average BP values to determine control, pharmacists evaluated the proportion of controlled home BP readings, where treatment intensification would be recommended if less than 75% of BP readings were controlled. HBPM and follow-up was continued for 12 months, then patients returned to usual care for hypertension management. Hypertension control rates were significantly higher among the HBPM cohort compared to usual care even at 18-months, 6-months after the HBPM intervention had ended [Citation18]. An extension of this trial found no significant difference in systolic or diastolic BP (DBP) at 54 months between HBPM and usual care groups, concluding that maintaining long-term BP control requires continued monitoring and resumption of HBPM intervention if BP increases [Citation19].

Home BP monitoring with additional management appears to improve hypertension control compared to usual care, but whether HBPM alone results in improved hypertension control was assessed in a randomised trial by Green et al. [Citation20]. Patients with uncontrolled hypertension despite antihypertensive therapy were eligible for one of three interventions: usual care, HBPM with results reported to their primary care physician (HBPM-PCP), or HBPM with pharmacist-management (HBPM-Pharmacist). Patients in both HBPM groups received training on appropriate use of a validated BP metre, and instructions to measure their BP at least twice per week, with two measurements each time. Home BP values were reported to PCPs or clinical pharmacists via a secure web-based messaging system. Patients randomised to the HBPM-Pharmacist group received follow-up management from clinical pharmacists every two weeks until their BP was controlled. The HBPM-Pharmacist group resulted in the largest proportion of patients with controlled in-clinic BP (defined as <140/90 mmHg) at 12-months [Citation20].

Discussion

Among the international guidelines for HBPM, there is overwhelmingly agreement among recommendations for using HBPM to assess and manage hypertension. Available guidelines provide similar recommendations for choosing a validated monitor and patient-preparation prior to BP measurements (empty bladder, resting for at least 5 min, using a monitor device with an arm cuff, and placing the BP cuff on bare skin) [Citation5,Citation8,Citation11,Citation12,Citation16]. Perhaps key to using HBPM is ensuring patients use a validated BP monitor and education on appropriate use and monitoring schedule. Specific resources where patients and clinicians can view validated BP monitors are provided in five guidelines [Citation6,Citation8,Citation14–16]. Recommended schedules to evaluate BP control in patients receiving antihypertensive medication were highly concordant in endorsing two measurements per day, in the morning before antihypertensive medication and in the evening, with 2 readings taken at least 1-minute apart each time. Additionally, at least 3-days of HBPM data and optimally 7-days is sufficient to assess BP control, with average home BP values 135/85 mmHg or higher indicating uncontrolled hypertension. Seven guidelines recommend omitting first-day readings due to concerns that these readings will likely be higher than subsequent day readings, and may increase the 7-day average [Citation6,Citation8,Citation11–14,Citation16,Citation17].

Recommendations with the greatest disagreement were related to guidance on timing of evening BP measurements. Among the guidelines reviewed, three offered no recommendation regarding evening BP measurements with regard to meals [Citation6,Citation7,Citation14], three recommend measuring before the evening meal [Citation8,Citation16,Citation17], three recommend measuring before bedtime [Citation5,Citation12,Citation13], and one guideline specifies measuring evening 2-hours after the evening meal [Citation11]. Postprandial hypotension, defined as a reduction in SBP of 20 mmHg or more within 2 h of a meal, is common in elderly patients and may or may not be symptomatic [Citation22]. To minimise the postprandial hypotension, which may produce artificially low evening BP values, evening BP should be measured before meals, or at least 2-hours after. When interpreting home BP readings, the average SBP and DBP should be used to assess BP control, rather than assessing the proportion of days controlled. Consistent among all included guidelines was an average home BP of 135/85 mmHg or higher corresponded to an office-measured BP of 140/90 mmHg or more, and should prompt treatment intensification. While most guidelines (6 out of 11) recommend routine calibration of home BP monitors against office-BP, specific details regarding when and how often this should be done are lacking. At a minimum, annual evaluation of patients’ HBPM technique and the accuracy of their HBPM seems appropriate.

Evidence supporting use of HBPM with additional management utilised a variety of HBPM schedules, none of which follow current recommendations. Although trials used different HBPM schedules, each used the same home BP threshold of ≥135/85 mmHg to guide antihypertensive intensification, thus the specific monitoring schedule may be less relevant than treatment intensification when average home BP readings are elevated. A 2017 meta-analysis evaluated changes in BP and control rates with HBPM compared to usual care, but categorised HBPM use by levels of additional co-interventions [Citation23]. Twenty trials with individual patient data were included, and stratified by intensity of co-intervention. Studies which used HBPM alone showed modest reductions in SBP and DBP at 12 months, and no significant improvement in BP control rates. However, studies which combined HBPM with more intense interventions, such as patient education and medication management, were associated with significant decreases in SBP (−6.1 mmHg) and DBP (−2.3 mmHg) [Citation23]. Additionally, patients who received HBPM with more intensive co-interventions were 40-50% more likely to achieve BP control compared to usual care [Citation23]. Thus, available data support greater reductions in SBP and DBP, as well as improved BP control rates, when HBPM is used along with additional patient education or medication management strategies.

Best practices related to HBPM for hypertension management should include standardised patient-education material, including written instructions clearly explaining proper measurement and monitoring schedule for obtaining home BP values. Additionally, a standardised approach for assessing BP control using home-monitored BP values according to current guidelines should be encouraged among all clinicians. Given that some clinicians may not be aware of recommendations for HBPM or evaluating home BP values, a recent statement on the use of self-measured BP monitoring from the American Heart Association and American Medical Association (AHA/AMA) has called for additional education for health care professionals to increase their knowledge and skills related to self-measured BP monitoring and ensure core competencies of HBPM in clinical practice [Citation9]. All clinicians involved in treating hypertension should be aware of the recommended monitoring schedule, as well as correctly interpreting home BP values to improve hypertension control rates.

Conclusion

Hypertension control rates remain unsatisfactorily low among patients treated with effective antihypertensive therapy. HBPM is recommended by multiple international hypertension guidelines as an effective way to assess BP control in patients treated with antihypertensive medications. Clinicians who recommend HBPM should educate patients on proper home BP measurement techniques, as well as recommend validated automatic monitors which measure BP from the upper arm. Available guidelines largely recommend a standardised HBPM schedule, including measuring BP twice per day for seven days, should be used to assess BP control. Averaged home BP values should be used to evaluate BP control, with prompt antihypertensive adjustment recommended if average home BP readings are above 135/85 mmHg, and close follow-up monitoring thereafter to ensure continued BP control.

Disclosure statement

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2021 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(8):e254–e743.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Hypertension Cascade: Hypertension Prevalence, Treatment and Control Estimates Among US Adults Aged 18 Years and Older Applying the Criteria From the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association’s 2017. Hypertension Guideline—NHANES 2013–2. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://millionhearts.hhs.gov/data-reports/hypertension-prevalence.html. Published 2019. Accessed November 3, 2020.

- Rethy L, Shah NS, Paparello JJ, et al. Trends in hypertension-related cardiovascular mortality in the United States, 2000 to 2018. Hypertension. 2020;76(3):e23–e25.

- Muntner P, Hardy ST, Fine LJ, et al. Trends in blood pressure control among US adults with hypertension, 1999-2000 to 2017-2018. JAMA. 2020;324(12):1190–1200.

- Muntner P, Shimbo D, Carey RM, et al. Measurement of blood pressure in humans: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2019;73(5):e35–e66.

- Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, et al. 2020 international society of hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2020;75(6):1334–1357.

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Authors/Task Force Members, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36(10):1953–2041.

- Stergiou GS, Palatini P, Parati G, et al. 2021 European society of hypertension practice guidelines for office and out-of-office blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens. 2021; [epub ahead of print].

- Shimbo D, Artinian NT, Basile JN, et al.; American Heart Association and the American Medical Association. Self-measured blood pressure monitoring at home: a joint policy statement from the American Heart Association and American Medical Association. Circulation. 2020;142(4):e42–e63.

- Tang O, Foti K, Miller ER, et al. Factors associated with physician recommendation of home blood pressure monitoring and blood pressure in the US population. Am J Hypertens. 2020;33(9):852–859.

- Rabi DM, McBrien KA, Sapir-Pichhadze R, et al. Hypertension Canada's 2020 comprehensive guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, risk assessment, and treatment of hypertension in adults and children. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36(5):596–624.

- Kario K, Park S, Buranakitjaroen P, et al. Guidance on home blood pressure monitoring: a statement of the HOPE asia network. J Clin Hypertens. 2018;20(3):456–461.

- Lin HJ, Wang TD, Yu-Chih CM, et al. 2020 consensus statement of the taiwan hypertension society and the taiwan society of cardiology on home blood pressure monitoring for the management of arterial hypertension. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2020;36(6):537–561.

- British Hypertension Society. Home blood pressure monitoring protocol. Available from: https://bihsoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Protocol.pdf

- Wang JG, Bu PL, Chen LY, et al. 2019 Chinese hypertension league guidelines on home blood pressure monitoring. J Clin Hypertens. 2020;22(3):378–383.

- Sharman JE, Howes F, Head GA, et al. How to measure home blood pressure: recommendations for healthcare professionals and patients. Aust Fam Physician. 2016;45(1):31–34.

- Villar R, Sánchez RA, Boggia J, et al. Recommendations for home blood pressure monitoring in latin American countries: a Latin American Society of hypertension position paper. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2020;22(4):544–554.

- Margolis KL, Asche SE, Bergdall AR, et al. Effect of home blood pressure telemonitoring and pharmacist management on blood pressure control: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(1):46–56.

- Margolis KL, Asche SE, Dehmer SP, et al. Long-term outcomes of the effects of home blood pressure telemonitoring and pharmacist management on blood pressure among adults with uncontrolled hypertension: follow-up of a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(5):e181617.

- Green BB, Cook AJ, Ralston JD, et al. Effectiveness of home blood pressure monitoring, Web communication, and pharmacist care on hypertension control: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(24):2857–2867.

- Magid DJ, Olson KL, Billups SJ, et al. A pharmacist-led, American Heart Association Heart360 web-enabled home blood pressure monitoring program. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(2):157–163.

- Madden KM, Feldman B, Meneilly GS. Blood pressure measurement and the prevalence of postprandial hypotension. Clin Invest Med. 2019;42(1):E39–E46.

- Tucker KL, Sheppard JP, Stevens R, et al. Self-monitoring of blood pressure in hypertension: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2017;14(9):e1002389..