Abstract

Purpose

In a pilot study including 35 patients with apparently treatment-resistant hypertension (ATRH), we documented associations between psychological profile, drug adherence and severity of hypertension. The current study aims to confirm and expand our findings in a larger and more representative sample of patients with ATRH, using controlled hypertensive patients as the comparator.

Materials and Methods

Patients with ATRH were enrolled in hypertension centres from Brussels and Torino. The psychological profile was assessed using five validated questionnaires. Drug adherence was assessed by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis of urine samples, and drug resistance by 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure was adjusted for drug adherence.

Results

The study sample totalised 144 patients, including 81 ATRH and 63 controlled hypertensive patients. The mean adherence level was significantly lower in the “resistant” group (78.9% versus 92.7% in controlled patients, p-value = .022). In patients with ATRH, independent predictors of poor drug adherence were somatisation, smoking and low acceptance level of difficult situations, accounting for 41% of the variability in drug adherence. Independent predictors of severity of hypertension were somatisation, smoking, more frequent admissions to the emergency department and low acceptation, accounting for 63% of the variability in the severity of hypertension. In contrast, in patients with controlled hypertension, the single predictors of either drug adherence or severity of hypertension were the number of years of hypertension and, for the severity of hypertension, alcohol consumption, accounting for only 15–20% of the variability.

Conclusion

Psychological factors, mostly related to somatisation and expression of emotions are strong, independent predictors of both drug adherence and severity of hypertension in ATRH but not in controlled hypertensive patients.

Plain language summary

This study included 144 patients with Apparently-Treatment Resistant (ATRH) or controlled Hypertension:

Patients with ATRH were more often poorly adherent to antihypertensive treatment than controlled hypertensive patients.

In patients with ARTH but not patients with controlled hypertension, psychological traits were strong, independent predictors of drug adherence and severity of hypertension, over and above demographic and health-related factors.

In patients with ATRH, the tendency to somatize, i.e. expressing somatic symptoms that cannot be adequately explained by organic findings was the most potent predictor of both poor drug adherence and severity of hypertension.

These patients also often presented alterations in the expression of emotions. It may be hypothesised that subjects who have difficulties identifying and expressing emotions with words will express them by physical complaints, and, in the mid-long term, might develop overt diseases.

In addition to more classical lifestyle and drug management and irrespective of their drug adherence level, patients with ATRH may benefit in priority from psychological evaluation and interventions. However, this needs to be studied in an interventional trial in the future.

Introduction

Resistant hypertension has been defined as the failure to achieve an office blood pressure (BP) <140/90 mmHg and a 24-hour ambulatory BP <130/80 mmHg on optimal doses of at least three antihypertensive medications from different classes (ideally one of which is a diuretic) [Citation1]. It is characterised by a higher prevalence of target organ damage [Citation2] and a higher incidence of cardiovascular events [Citation3] compared with other forms of hypertension.

Many patients with apparent resistant hypertension are in fact pseudo-resistant due to poor drug adherence [Citation4–6]. However, whatever the approach used, drug adherence is difficult to assess and varies over time [Citation4,Citation7]. This is particularly true in patients with difficult-to-treat, severe hypertension included in most renal denervation trials [Citation4,Citation8,Citation9]. Such patients may indeed show variable levels of drug adherence during follow-up but also at different stages of their disease, raising the question of whether difficulty to achieve BP control was initially due to poor drug adherence or to the characteristics of hypertension per se (“chicken and egg” paradox). Therefore, the frontier between truly and pseudo-resistant hypertension is fluctuating, and patients may shift from one group to the other and vice versa. Accordingly, many authors prefer to consider these patients in a single category, i.e. “apparently treatment-resistant hypertension” (ATRH) [Citation4,Citation10,Citation11].

Beyond classic demographic and health-related characteristics, psychological traits may influence both drug adherence to antihypertensive treatment and the severity of hypertension. This appears to be particularly the case in patients with difficult-to-treat hypertension [Citation9,Citation12]. In a pilot study performed on 35 patients with particularly severe ATRH, predictors of poor drug adherence were recent hospital admission for hypertension, a lower ability to put things into perspective when facing negative events and a higher tendency to somatize [Citation13]. Independent predictors of treatment resistance were a higher recourse to the strategies of blaming others and oneself. Furthermore, a high proportion of patients manifested symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, such as avoidance and emotional blunting [Citation12].

The current study aims to further expand our previous findings in a larger and more representative sample of patients with ATRH enrolled in Brussels and Torino Hypertension Excellence Centres, using as a comparator a sample of patients with controlled hypertension from the same centres. In all participants, we collected a wide array of demographic, clinical and psychological variables and assessed drug adherence by chemical detection of drugs in the urine. The severity of hypertension was established based on 24-h ambulatory blood pressure level, after adjustment for drug adherence level and the number of antihypertensive drugs. In a second step, we looked for independent predictors of drug adherence and severity of hypertension, both in patients with ATRH and controlled hypertension.

Methods

Study population

The recruitment period extended from October 2017 to June 2021 for the Department of Cardiology of the Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc (Brussels, Belgium) and from January 2019 to June 2021 for the Torino Hypertension Expert Centre (Torino, Italy).

All consecutive patients with ATRH confirmed by ambulatory BP monitoring (24-hour BP ≥130/80 mmHg on 3 or more antihypertensive drug classes at optimal/maximal tolerated drug dosages) [Citation1] seen during this time frame who signed the informed consent were included in the analysis. In parallel, we enrolled a series of hypertensive patients with 24-h ambulatory BP <130/80 mmHg on antihypertensive treatment, later referred to as “controlled hypertensive patients”. For both cohorts, exclusion criteria were age <18 years, estimated glomerular filtration (eGFR) <30 ml/min/1.73 m2 according to the CKD-EPI formula, body mass index ≥40 Kg/m2 and a history of myocardial infarction, stroke or polyvascular disease.

All patients with ATRH as well as patients with milder forms of hypertension diagnosed <30 years old underwent detailed endocrine and vascular work-up for secondary hypertension, also including in most cases an MR- or CT-angiography (many of them being initially referred for evaluation for renal denervation) as recommended in the guidelines. Other patients from the “controlled group” were evaluated according to history and clinical presentation, for example, primary aldosteronism was searched for in case of incidental finding of an adrenal mass or low plasma potassium, and renal Duplex was performed in young/middle-aged women to exclude renal fibromuscular dysplasia.

Office and 24-hour ambulatory BP values were measured using validated oscillometric devices (see below). For all recruited patients, a detailed clinical history and physical examination were available, and a urine sample of 10 mL was collected. Five validated questionnaires were administered in order to assess different facets of their psychological profile, as well as past traumas and subsequent posttraumatic stress disorders. The duration of the whole procedure was ∼ 60 min. Urines were collected on the day of the signature of the written informed consent. This was a compromise between the ethical need to correctly inform the patient and the necessity to avoid interfering in medication-taking behaviour [Citation12]. The study was approved by the Comité d’Ethique Hospitalo-Facultaire des Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc (Brussels) and the Comitato Etico Interaziendale of the A.O.U. Città della Salute e della Scienza (Torino), and was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent modifications.

Assessment tools

Blood pressure measurement

Office blood pressure

Blood pressure was measured according to the European guidelines from the European Society of Hypertension [Citation1] using the validated oscillometric device Omron HEM 907 (Omron Health Care, Kyoto, Japan), after a 5-minute silent rest in a seated position following all good practice recommendations [Citation14]. Three measurements were obtained at 1 min from each other and the mean value was used in subsequent analyses.

24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring

Twenty-four-hour ambulatory BP values were measured using an automated, non-invasive oscillometric device, the validated Mobil O Graph, I.E.M (Mobil O Graph, I.E.MGmbH, Stolberg, Germany), re-cording BP measurements at 30 min intervals throughout 24 h, with at least 20 valid measurements during day-time (between 6h00 and 23h00) and 7 at night-time (between 23h00 and 6h00) [Citation15]. Assessment of the severity of hypertension was based on mean 24-hour systolic BP, adjusted for the number of antihypertensive drugs and adherence level.

Biochemical analysis (urine LC-MS/MS)

All patients were provided a 10 mL urine sample, stored at a temperature of −20 °C before analysis. Detection of antihypertensive drugs in the urine was performed using a liquid chromatography system coupled with a tandem mass spectrometer as a detector (LC-MS/MS). Briefly, an ethyl acetate extraction (1 mL) of 200 µL aliquots of urine was performed after adding internal standards. After mixing and centrifugation, the organic phase was evaporated. The dry residue was reconstituted with 100 µL of 0.1% formic acid/acetonitrile (80:20, v/v) and analysed by LC-MS/MS [Citation8,Citation16]. All prescribed antihypertensive drugs and metabolites were detectable. Full drug adherence, partial drug adherence and total non-adherence were defined as the presence of all, part or none of the prescribed drugs in the urine, respectively. Drug adherence was defined as the percentage of prescribed antihypertensive drugs which were effectively detected in the urine.

Psychological analysis

In order to get a broad picture of the psychological profile of hypertensive patients, five validated questionnaires were used: the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) [Citation17–19]; the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) [Citation20,Citation21]; The Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) [Citation22]; The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) [Citation23] and the Post Traumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS) [Citation24]. Explanations on the questionnaires and their interpretation are provided in the Online Supplement. Of note, the CERQ was not available in the Italian version, therefore this questionnaire was not administered to participants from Torino.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York). Categorical variables are reported as percentages and continuous data as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Patients with ATRH and controlled hypertension were compared on clinical and demographic variables using t-tests and Chi-Square tests as appropriate. Pearson’s (for normally distributed variables) and Spearman’s correlations (for those that were not) were used to investigate the associations between adherence level defined as the percentage of prescribed antihypertensive drugs detected in the urine and demographic, health-related and psychological variables. Correlations were also run between demographic, health-related and psychological variables and the residuals of 24-hour ambulatory systolic BP, regressed on the adherence level and the number of antihypertensive drugs per day, considered as reflecting the severity of hypertension. Independent t-tests and ANOVA’s were further used to clarify significant correlations involving continuous variables. Finally, multivariate linear regression analyses were performed to investigate which factors, among the significantly correlated (with p < 0.05 as the level of significance) demographic, health-related and/or psychological variables were independent predictors of adherence level and severity of hypertension. All analysis were adjusted for centre. Collinearity was checked with a matrix of Pearson’s correlations with r ≥ 0.8 in at least one correlation as the criterion for multicollinearity and with the variance inflation factor (VIF) (exclusion of multicollinearity if all VIF < 10) [Citation25].

Results

Characteristics of ATRH and controlled hypertensive patients

Between October 2017 and June 2021, a total of 144 consecutive patients were enrolled, 95 in Brussels (Belgium) and 49 in Torino (Italy). The study sample included 81 patients with ATRH and 63 patients with controlled hypertension.

As expected, patients with ATRH had higher office BP (157/91 ± 27/17 versus 140/79 ± 18/12; p-value <.001) and ambulatory BP (144/89 ± 16/12 versus; 119/71 ± 6/6; p < .001) on a higher number of prescribed antihypertensive drug classes (4.1 ± 1.2 versus 2.4 ± 1.2, p < .001). Furthermore, “resistant” patients were more often of African descent (14.8% versus 1.6%, p = .006) and overweight (BMI 29.8 ± 4.6 Kg/m2 versus 28.1 ± 5.1 Kg/m2, p = .037), and on antihypertensive treatment for a longer period of time (16 ± 10 years versus 11 ± 11, p = .005) ().

Table 1. Characteristics of apparently treatment-resistant and controlled hypertensive patients.

Drug adherence

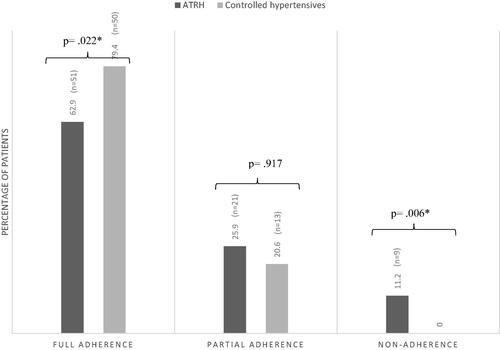

Mean drug adherence was significantly lower in patients with ATRH (78.9% versus 92.7% in controlled patients, p = .022). Furthermore, the distribution of drug adherence (full adherence, partial adherence and total non-adherence) was substantially different in both groups. In particular, all totally non-adherent patients were found in the resistant group ().

Correlations between drug adherence and demographic, health-related and psychological variables

In patients with ATRH, adherence level, defined as the proportion of prescribed antihypertensive drugs detected in the urine was associated with general characteristics such as age, smoking status, the fact to live with a partner, the yearly number of admissions to the emergency department for hypertension, and family history of hypertension. Notably, adherence level was also significantly associated with a number of psychological traits: difficulty to describe feelings (TAS, r = −.247; p = .019), total alexithymia (TAS, r = −.265; p = .048), acceptation (CERQ, r = .321; p = .018), planification (CERQ, r = .362; p = .007), adaptive strategies (CERQ, r = .374; p = .006), anxiety (BSI, r = −.286; p = .017) and somatisation (BSI, r = −.469; p = .001). By contrast, in controlled hypertensive patients, the single parameter significantly correlated with adherence level was the number of years with hypertension (r = −.412; p = .019) ().

Table 2. Correlations between socio-demographic, health-related and psychological variables and adherence level.

Correlations between severity of hypertension and demographic, health-related and psychological variables

In patients with ATRH, the severity of hypertension, defined as mean 24-hour systolic BP adjusted for adherence level and the number of antihypertensive drugs prescribed, was significantly correlated with age, smoking status, and the fact to live with a partner and the number of admissions at the emergency department. Concerning psychological parameters, the severity of hypertension was significantly associated with acceptation (CERQ, r = −.322, p = .018), planification (CERQ, r = −.272, p = .031), adaptive strategies (CERQ, r = −.267, p = .037), anxiety (BSI, r = .316, p = .010), and somatisation (BSI, r = .463, p ≤ .001) ().

Table 3. Correlation between socio-demographic, health-related and psychological variables and severity of hypertension based on 24-h Ambulatory Systolic BP.

In the subgroup of controlled hypertensive patients, the severity of hypertension was only correlated with alcohol consumption, education level and the number of years on antihypertensive treatment (r = .363, p = .008; r = −.385, p = .010; and r = .361, p = .042, respectively) ().

Predictive analyses

For predictive analyses, all demographic, health-related and psychological variables that were significantly correlated with the variable of interest were included in the models as potential predictors of drug adherence or severity of hypertension.

Regression analysis on the adherence level

In the ATRH group, eleven variables were included in the model for the prediction of the adherence level: age, smoking status, living with a partner, number of admissions to the emergency department for hypertension, family history of hypertension, the difficulty to describe feelings factors and the total alexithymia scores (TAS-20), the acceptation and planification subscales (CERQ) and the somatisation and anxiety factors (BSI) ().

Table 4. Multivariable regression with stepwise backward selection for prediction of adherence level and severity of hypertension in patients with apparently treatment-resistant and controlled hypertension.

Three predictors of poor adherence level remained in the final model, from the best predictor to the last one: somatisation, active smoking and low acceptance of difficult situations. This model accounted for 40.6% (adjusted R2) of the variability in adherence level. By contrast, in the controlled group, the single variable included in the model as a potential predictor of adherence level was the number of years on antihypertensive treatment (a long time since diagnosis of HTN being correlated with poorer drug adherence), accounting for only 15.3% of the variability (adjusted R2) ().

Regression analyses on severity of hypertension

In the ATRH group, nine variables were included in the model for the prediction of the severity of hypertension: age, smoking status, living with a partner, number of admissions at the emergency department, the acceptation and planification subscales of the CERQ, and the somatisation and anxiety factors of the BSI. Four predictors remained in the final model, from the best predictor to the last one: somatisation, smoking status, number of hospital admissions for hypertension and finally, low acceptation of difficult situations. This model accounted for about 63.2% (adjusted R2) of the variability of the severity of hypertension.

In the controlled hypertensive group, three variables were included in the model as potential predictors of severity of hypertension: alcohol consumption, a lower education level and the number of years on an antihypertensive regimen. Only two predictors remained in the final model, the number of years with treated hypertension followed by alcohol consumption, accounting for 17.1% (adjusted R2) of the variability in the severity of hypertension ().

Exploratory analysis in patients with ATRH according to adherence status

In order to further refine our analysis we divided our sample into fully adherent patients (n = 50), subsequently labelled “truly resistant” hypertensive patients and poorly/non-adherent patients (n = 31). Compared with truly resistant hypertensive patients, poor adherers tended to be younger, had both higher office and ambulatory blood pressure despite prescription of a higher number of antihypertensive drugs, were five-fold more often admitted for hypertension at the emergency room and three-fold more often smokers (Supplementary Table S1). Low adherence was associated with a lower capacity for positive refocusing and adaptive strategies when facing difficult life events, higher anxiety and somatisation. (Supplementary Table S2). While in patients with truly resistant hypertension the severity of hypertension was associated both with limb arteriopathy (likely a proxy for arterial damage/stiffened arteries) and psychological factors such as a lower capacity to put into perspective and professional and social impairments, in poor adherers the single predictors of hypertension severity were of psychological nature, namely a low capacity to develop adaptive strategies, a higher tendency to anxiety and somatisation, as well as a higher number of previous traumas (Supplementary Table S3).

Discussion

The main findings of this study can be summarised as follows: (i) patients with ATRH are more often poorly adherent to antihypertensive treatment than controlled hypertensive patients; (ii) in such patients, psychological traits are strong, independent predictors of drug adherence and severity of hypertension, over and above demographic and health-related factors; (iii) by contrast, in controlled hypertensive patients, psychological characteristics do not predict either drug adherence or severity of hypertension; (iv) in patients with ATRH, somatisation appears to be the most potent predictor of both poor drug adherence and severity of hypertension; (v) subgroup analysis shows that distinct psychological factors are associated with severity of hypertension both in truly resistant and poorly/non-adherent patients with ATRH.

First, as expected, our findings confirm a high prevalence of non- or poor drug adherence in patients with ATRH. Indeed, the mean adherence level was significantly lower in this group than in controlled patients (78.9% versus 92.7%, p = .022). Furthermore, patients who did not take any prescribed medication were all found in the resistant hypertensive subgroup. This is in line with previous studies documenting a high proportion of non-adherence ranging from 9 to 35% in ATRH patients [Citation4,Citation26,Citation27].

Second, we confirm and further expand previous findings from our and other groups showing the relation between hypertension and the expression of emotions. A large body of evidence supports the association between hypertension and alexithymia, a phenomenon characterised by difficulties to identify feelings, finding appropriate words to describe them and distinguishing feelings from bodily sensations, and by an externally-oriented style of thinking [Citation28]. Furthermore, in our pilot study including patients with severe ATRH [Citation12], we have identified correlations between drug adherence and severity of hypertension on one side, expression of emotions and difficulties to put life events into perspective on the other side. Along the same lines, in another study of our group [Citation9], cognitive reappraisal appeared as a single independent predictor of eventual blood pressure control in patients with initially resistant hypertension.

Similarly, in the current study, alexithymia, factors related to the expression of emotions and maladaptive emotional strategies were found to be associated with poor drug adherence, the severity of hypertension or both in patients with resistant hypertension. However, the most potent, independent psychological factor associated with poor drug adherence and the level of drug resistance was somatisation, already identified as an independent predictor of drug adherence in our previous study [Citation12].

Somatisation, defined as expressing somatic symptoms that cannot be adequately explained by organic findings [Citation13], has been associated with alexithymia and disturbed expression of emotions, both in population studies [Citation29,Citation30] and different pathological situations [Citation31,Citation32]. It may be hypothesised that subjects who have difficulties identifying and expressing emotions with words will express them by physical complaints, and, in the mid-long term, might even develop overt diseases. In the case of hypertension, this may result from the activation of the autonomic nervous system or hormonal cascades such as the renin-angiotensin system [Citation12].

Interestingly, in this study, psychological factors associated with poor drug adherence and the degree of drug resistance were very similar. While this may to some extent reflect methodological difficulties in fully separating both aspects, it supports the idea of a continuum between difficult-to-treat, poorly adherent patients with severe hypertension and “truly resistant” hypertensive patients. We have discussed this dynamic process elsewhere [Citation9], where an initially adherent patient may for example neglect her/his antihypertensive treatment due to treatment failure, then become truly resistant following the development of arterial hypertrophy and target organ damage.

This study has to be interpreted within the context of its limitations. First, despite being increasingly considered the gold standard, LC-MS/MS is mostly a qualitative method, and pharmacokinetic individual characteristics, renal and liver function, as well as drug half-lives, may influence the results [Citation4,Citation7]. Secondly, chemical detection of drugs was performed only at a one-time point, in the context of a consultation, and the possibility of a “toothbrush effect” [Citation33] cannot be discarded. Third, 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring was performed in the context of daily clinical practice, typically within one week of the consultation where informed consent was obtained and urine sample for drug monitoring was collected. Therefore, we cannot exclude subtle differences in the level of ambulatory blood pressure between the day of ambulatory BP monitoring and the day of urine sampling. However, this is unlikely to have affected the classification between controlled patients and patients with ATRH, because the latter were usually known as such for months, if not for years. Finally, this cross-sectional study is unable to capture the dynamic character, not only of drug adherence but also of human psychology and physiology. Our study can only provide information on associations between psychological factors, drug adherence and drug resistance at a given time point, and causal inferences should be considered as speculative.

Still, our results provide further support to the implication of psychological factors in the pathogenesis and maintenance of severe forms of hypertension, likely both via activation of physiological pathways and influence on drug-taking behaviour and lifestyle (for example smoking) [Citation12]. Our findings suggest that psychological factors are mostly involved in difficult-to-treat/resistant forms of hypertension, at least in Western countries such as Belgium and Italy. The current results complement another study from our group [Citation34] showing the importance of altered expression of emotions and post-traumatic stress disorder in milder forms of hypertension in an African population chronically exposed to violence. Hypertensive patients belonging to these different categories – i.e. with ATRH and/or coming from regions chronically exposed to violence such as migrants and refugees – could benefit in priority from psychological evaluation and interventions [Citation4]. Future studies should aim at following prospectively patients with ATRH, with repeated evaluation of drug adherence, and testing the efficacy of various psychological approaches to improve blood pressure control, as well as physical and psychological well-being.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25.5 KB)Acknowledgements

Alexandre Persu and Philippe de Timary are Cliniciens-Chercheurs Spécialistes Qualifiés of Fonds Cliniques de Recherche of UCLouvain, Belgium. During her PhD, Coralie Georges was partly supported by the Fondation Camille et Germaine Damman, the Fondation-Institut de Recherche Médicale (http://www.f-mri.org/) and educational grants from Ablative Solution, Recor Medical and Servier.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021–3104.

- Muiesan ML, Salvetti M, Rizzoni D, et al. Resistant hypertension and target organ damage. Hypertens Res. 2013;36(6):485–491.

- Daugherty SL, Powers DJ, Magid DJ, et al. Incidence and prognosis of resistant hypertension in hypertensive patients. Circulation. 2012;125(13):1635–1642.

- Berra E, Azizi M, Capron A, et al. Evaluation of adherence should become an integral part of assessment of patients with apparently treatment-resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2016;68(2):297–306.

- Eskås PA, Heimark S, Eek Mariampillai J, et al. Adherence to medication and drug monitoring in apparent treatment-resistant hypertension. Blood Press. 2016;25(4):199–205.

- Choudhry NK, Kronish IM, Vongpatanasin W, et al. Medication adherence and blood pressure control: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2022;79(1):e1–e14.

- Lane D, Lawson A, Burns A, et al. Nonadherence in hypertension: how to develop and implement chemical adherence testing. Hypertension. 2022;79(1):12–23.

- Wunder C, Persu A, Lengelé J-P, et al. Adherence to antihypertensive drug treatment in patients with apparently treatment-resistant hypertension in the INSPiRED pilot study. Blood Press. 2019;28(3):168–172.

- Pappaccogli M, Di Monaco S, Georges CMG, et al. Predictors of blood pressure control in patients with resistant hypertension after intensive management in two expert centres: the Brussels-Torino experience. Blood Press. 2019;28(5):336–344.

- Judd E, Calhoun DA, Judd E, et al. Apparent and true resistant hypertension: definition, prevalence and outcomes. J Hum Hypertens. 2014;28(8):463–368.

- Maw AM, Thompson LE, Ho PM, et al. Implications of guideline updates for the management of apparent treatment resistant hypertension in the United States (a NCDR research to practice [R2P] project). Am J Cardiol. 2020;125(1):63–67.

- Petit G, Berra E, Georges CMG, et al. Impact of psychological profile on drug adherence and drug resistance in patients with apparently treatment-resistant hypertension. Blood Press. 2018;27(6):358–367.

- Kellner S. Theories and research. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990;178(3):150–160.

- Stergiou GS, Palatini P, Parati G, et al. 2021 European society of hypertension practice guidelines for office and out-of-office blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens. 2021;39(7):1293–1302.

- O'Brien E, Parati G, Stergiou G, et al. European society of hypertension position paper on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 2013;31(9):1731–1768.

- Jung O, Gechter JL, Wunder C, et al. Resistant hypertension? Assessment of adherence by toxicological urine analysis. J Hypertens. 2013;31(4):766–774.

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implication for affect, relationships and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(2):348–362.

- Ioannidis CA, Siegling AB. Criterion and incremental validity of the emotion regulation questionnaire. Front Psychol. 2015;6:247.

- Cutuli D. Cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression strategies role in the emotion regulation: an overview on their modulatory effects and neural correlates. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8:175.

- Garnefski N, Legerstee J, Kraaij VV, et al. Cognitive coping strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety: a comparison between adolescents and adults. J Adolesc. 2002;25(6):603–611.

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personal Individ Differ. 2001;30(8):1311–1327.

- Bagby RM, Parker JDA, Taylor GJ. The twenty-item toronto alexithymia Scale-I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38(1):23–32.

- Derogatis LR. Brief symptom inventory: BSI; administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: Pearson; 1993.

- Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, et al. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Psychol Assess. 1997;9(4):445–451.

- Bowerman O. Linear statistical models. Thomson Q2 Wadsworth, Belmond (California); 1990.

- de Jager RL, van Maarseveen EM, Bots ML, et al. Medication adherence in patients with apparent resistant hypertension: findings from the SYMPATHY trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(1):18–24.

- Gupta P, Patel P, Strauch B, et al. Risk factors for nonadherence to antihypertensive treatment. Hypertension. 2017;69(6):1113–1120.

- Casagrande M, Mingarelli A, Guarino A, et al. Alexithymia: a facet of uncontrolled hypertension. Int J Psychophysiol. 2019;146:180–189.

- Bailey PE, Henry JD. Alexithymia, somatization and negative effects in a community sample. Psychiatry Res. 2007;150(1):13–20.

- Mattila AK, Kronholm E, Jula A, et al. Alexithymia and somatization in general population. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(6):716–722.

- Liu L, Cohen S, Schulz MS, et al. Sources of somatization: exploring the roles of insecurity in relationships and styles of anger experience and expression. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(9):1436–1443.

- Raffagnato A, Angelico C, Valentini P, et al. Using the body when there are no words for feelings: alexithymia and somatization in self-harming adolescents. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:262.

- Burnier M, Wuerzner G, Struijker-Boudier H, et al. Measuring, analyzing, and managing drug adherence in resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;62(2):218–225.

- Bapolisi A, Maurage P, Pappaccogli M, et al. Association between post-traumatic stress disorder and hypertension in congolese exposed to violence: a case-control study. J Hypertens. 2022;40(4):685–691.