I am sure that all the readers have heard about Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). I am also certain that most of us recognise the general importance of stress, depression, loneliness and social isolation in our lives and their relationship with hypertension and other non-transmissible diseases [Citation1–5]. However, PTSD is an especially disturbing entity, so much so that words – and as humans we are bound to vocal expression – fall short when you get to the explaining part. So, when you try to explain exactly what war veterans’ PTSD is, a wide understanding is necessary. In this respect, I recently found out that several studies are assessing the relationship between PTSD and hypertension, in Europe [Citation5]. It is now well accepted that there is a connection between PTSD and increased cardiovascular risk [Citation6–8]. This interest in PTSD seems to spur in the wake of the horrible war in the Ukraine. War is next door and, certainly, it touches us all…

Why am I, a cardiologist devoted to hypertension and cardiovascular risk, such an expert? Clearly, I am not an expert, except for my firsthand experience as a medical officer in the Portuguese Navy. Like everything else in human emotions, you can know a lot about a certain theme, but living it is something else…Truthfully, I seldom talk about my war experiences, like many other combatants either with or without a formal PTSD diagnosis.

Former fighters get together often. War makes for a strong bond. Some say it is the strongest possible bond and I tend to agree. Veterans do not like to talk about their traumatic experiences, not even to their closest family. Repeated deployment already burdens military families [Citation9–11] even without veteran’s PTSD. Instead, the conversation focusses on the many comic events experienced, like the details of food, the occasional drunkenness of a few, the lice infestation, or the dengue outbreak. Nobody talks about the fear, the noise in their souls, or the longing for the world to be different. As a doctor – even when you are not directly under fire – you are called to tend for wounded or sick comrades and, commonly, to help suffering civilians, innocent victims of a political chess board they do not understand…

Quite often, you remember the laments of dying people, from many fields from Africa and some others in Asia (like East Timor, where I worked for quite some time). In these faraway places people die from treatable diseases, such as a light cut in a foot or a common upper respiratory infection, both hard challenges to an immune system in overload from malaria, malnutrition, etc. You are faced with a different type of medicine, where abdominal palpation is sufficient for the diagnosis of appendicitis, auscultation will help in the diagnosis of tuberculosis and a heart murmur is commonly associated with a scourge called rheumatic fever, still very common in the poor world.

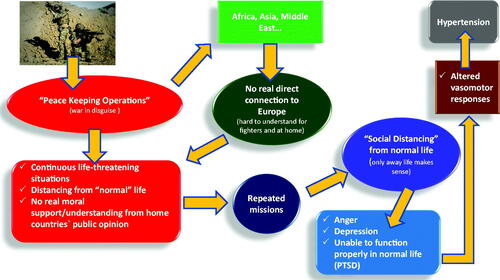

You work for long hours, with basic medical kits, doing the best you can, in makeshift hospitals, in unreal locations, with very real people. You realise later that all this work comes at an extra cost. You will forever hear the cries of those left behind for ‘critical’ political reasons, or simply that could not be saved with the resources available. You remember their faces, their frail bodies, the smell, and the heat, as vividly as if you were there. That is my own heritage, my own personal silent suffering. Such experiences, and the clinical follow-up of many of the fighters sent to hold the peace everywhere, allowed me to produce the graphical abstract above – It is just a personal insight for PTSD (). The reader will notice that lack of recognition, from public opinion at home, seems important. Indeed, many veterans feel that people just don’t care. This, understandably, is an important issue for them and their families.

Figure 1. The reality of the fighters from most European countries: (1) Forces are sent to active and dangerous places, under the guise of ‘Peace Keeping Operations’; (2) Repeated missions and lack of understanding from public opinion send them away from normal life; (3) Psychological suffering ensues, followed by deep anger and, occasionally, serious depression; (4) Severely altered lifestyle (PTSD) and continuous emotional stress promote hypertension.

Some war veterans isolate themselves. In other cases, their families cannot hold their aggression, this truly makes adhesion to chronic disease therapy very hard and loneliness does kill [Citation12]. Others prefer to sleep in lighted, noisy environments, so their life cycle is inverted: they are awake at night and sleep during the day. Darkness and silence bring about bad memories. War is very loud. There are the sounds of mortars, small arms fire very close and, if you are a doctor, the sounds of the wounded and sick, or their sudden silence…Many are not able to hold a paying job. Further isolation leads to increased suffering and in some cases, suicide in a trailer somewhere. Those are the people who’s wars are still raging.

Portugal, a small country in western Europe, was a colonial power, with important colonies in Africa, such as Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, or in other latitudes, like East Timor. These countries were, and some still are, involved in political turmoil, escalating to war at times (…such is the case in present-day Northern Mozambique [Citation13]). The small Portuguese Armed Forces have also contributed to NATO efforts in non-traditional geographies, like Afghanistan and Iraq. So, while ‘not in war’, we have always been involved in conflict, many under the guise of ‘Peace Keeping Operations’, a strange and dangerous euphemism…

The current war in Ukraine has caught the attention of many. I don’t like to see the images, because they bring forth ghosts from days past, turned real. I am sure combatants in both sides will eventually suffer the same ordeals and end up with PTSD. As someone who has seen war up close, I plainly wish war in Europe would end quickly. Unfortunately, mankind’s memory is short lived. As I write this text – produced upon a gentle friend’s invitation – the Ukraine war is at a stalemate, with verbal aggression and ever increasing threats. This situation may be indicative of the need for a ‘Peace Keeping Operation’ in Europe. This would involve a serious escalating of the conflict, with massive movements of troops already on the borders of the Ukraine.

Lastly, I dearly wish to thank my family and the many friends who closely work with me. I must apologise, for the ‘stiffness’ I display at times. This is often the sure sign of people who lived alongside avoidable death for too long. I also want to salute all those that shared risks with me, in unforgotten conflicts, they truly deserve our wholehearted respect. Veterans will understand fully these words (and all that could not be written in this text…). Peace will certainly prevail since there is no acceptable alternative. So, yes, war veterans’ PTSD is related to hypertension and to a lot of other disorders, but to study veterans one does need a wide understanding from where they came from and the ordeals to which they were (are) subjected to.…

References

- Kreutz R, Dobrowolski P, Prejbisz A, et al. Lifestyle, psychological, socioeconomic and environmental factors and their impact on hypertension during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. J Hypertens. 2021;39(6):1077–1089.

- Golaszewski NM, Lacroix AZ, Godino JG, et al. Evaluation of social isolation, loneliness, and cardiovascular disease among older women in the US key points + supplemental content. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2146461.

- Gaio V, Rodrigues AP, Kislaya I, et al. Estimation of the 10-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in the Portuguese population: results from the First Portuguese Health Examination Survey (INSEF 2015). Acta Med Port. 2020;33(11):726–732.

- Rodrigues AP, Gaio V, Kislaya I, et al. Sociodemographic disparities in hypertension prevalence: results from the first Portuguese National Health Examination Survey. Rev Port Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2019;38(8):547–555.

- Persu A, Petit G, Georges C, et al. Hypertension, a posttraumatic stress disorder? Time to widen our perspective. Hypertension. 2018;71(5):811–812.

- Kibler JL. Posttraumatic stress and cardiovascular disease risk. J Trauma Dissociation. 2009;10(2):135–150.

- Kibler JL, Joshi K, Ma M. Hypertension in relation to posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Behav Med. 2009;34(4):125–132.

- Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Riviere LA, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among active component and national guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):614–623.

- Riggs SA, Cusimano A. The dynamics of military deployment in the family system: what makes a parent fit for duty? Fam Court Rev. 2014;52(3):381–399.

- Maholmes V. Adjustment of children and youth in military families: toward developmental understandings. Child Dev Perspect. 2012;6:430–435.

- Bóia A, Marques T, Francisco R, et al. International missions, marital relationships and parenting in military families: an exploratory study. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27(1):302–315.

- Wong CW, Kwok CS, Narain A, et al. Marital status and risk of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2018;104(23):1937–1948.

- War in Resource-Rich Northern Mozambique—Six Scenarios – Africa Center for Strategic Studies. [cited 2022 Aug 10]. https://africacenter.org/security-article/war-in-resource-rich-northern-mozambique-six-scenarios/