Abstract

Purpose

Little is known about the factors contributing to preeclampsia in Ethiopia. Therefore, this study was conducted to determine factors associated with preeclampsia among pregnant women in public hospitals.

Methods and materials

An institution based unmatched case-control study was conducted. Women with preeclampsia were cases, and those without preeclampsia were controls. The study participants were selected using the consecutive sampling method with a case-to-control ratio of 1:2. The data were collected through measurements and a face-to-face interview. Then the data were entered using Epi Info and exported to STATA 14 for analysis. The findings were presented in text, tables, and figures.

Results

About 51 (46.4%) of cases and 81 (36.8%) of controls had no formal education. Multiple gestational pregnancies (AOR = 2.75; 95% CI: 1.20–6.28); history of abortion (AOR = 3.17, 95% CI: 1.31–7.70); change of paternity (AOR = 3.16, 95% CI: 1.47–6.83); previous use of implants (AOR = 0.41; 95% CI: 0.13–0.96); and fruit intake during pregnancy (AOR = 0.36, 95% CI: 0.18–0.72) were associated factors of preeclampsia.

Conclusion

History of abortion, change of paternity, and multiple gestational pregnancies were risk factors for preeclampsia. Fruit intake during pregnancy and previous use of implant contraceptives were negatively associated with preeclampsia. Further studies should be conducted regarding the effect of prior implant use on preeclampsia. Healthcare providers should give special attention to women with a history of abortion and multiple gestational pregnancies during the ANC follow-up period.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) is the second leading cause (14.0%) of maternal mortality next to haemorrhage.

Preeclampsia is a common pregnancy problem that results in serious maternal and foetal complications.

Preeclampsia is associated with an increased risk of adverse foetal, neonatal, and maternal outcomes.

The majority of deaths due to preeclampsia could be prevented through timely and effective care provision for pregnant women.

There are limited studies conducted on the factors associated with preeclampsia in Ethiopia.

Introduction

Pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) is the second leading cause (14.0%) of maternal mortality, next to haemorrhage (27.1%) [Citation1]. PIH is associated with an increased risk of adverse foetal, neonatal, and maternal outcomes, including preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction, perinatal death, acute renal or hepatic failure, antepartum haemorrhage, postpartum haemorrhage, and maternal death worldwide [Citation1,Citation2]. About 10–16% of maternal mortality rates are caused by PIH in sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia [Citation3].

According to the latest International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP) updated guidelines, preeclampsia is gestational hypertension accompanied by one or more of the following new-onset conditions at ≥20 weeks’ gestation: Proteinuria, other maternal end-organ dysfunction, including neurological complications, pulmonary edoema, hematological complications, acute kidney infection, with or without right upper quadrant or epigastric abdominal pain, liver involvement, and uteroplacental dysfunction [Citation4]. It is one of the major obstetrical problems in developing countries, and the causes of most cases remain unknown [Citation5]. The impact of the disease is more severe in developing countries, where medical interventions are less effective due to the late admission of cases [Citation6].

Based on previous studies, the risk factors for preeclampsia include maternal age, educational status, previously existing hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and contraceptives [Citation7–10]. Preeclampsia occurs more frequently in primigravida [Citation11]. However, previous studies have had contradictory findings about some factors, like the history of abortion, previous hormonal contraceptive use, and the number of parities [Citation5,Citation8,Citation10,Citation11].

The pooled prevalence of PIH and preeclampsia in Ethiopia was 6.82% and 4.74%, respectively [Citation12]. Maternal deaths due to preeclampsia increased in Ethiopia, contrary to other maternal complications occurring during pregnancy. However, the majority of deaths due to preeclampsia could be prevented through timely and effective care provision for pregnant women. Most of the previous studies were conducted using cross-sectional study designs and the nature of the disease is rare. Hence, a case-control study design is the appropriate design for this rarely prevalent disease. There are limited studies conducted on the factors associated with preeclampsia in Ethiopia, particularly in the study area. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine factors associated with preeclampsia among pregnant women.

Methods and materials

Study area and period

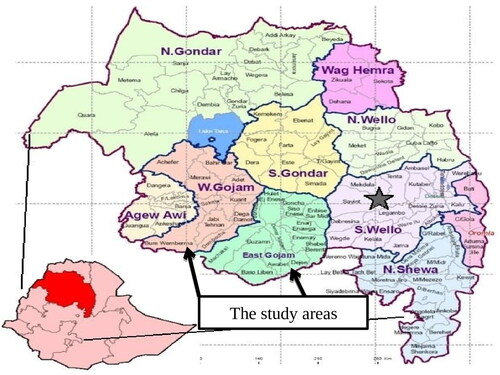

The study was conducted at Finote Selam General Hospital (FSGH), Asrade Primary Hospital (ADH), Shegaw Motta Primary Hospital (SMPH), and Debre Markos Comprehensive and Specialised Hospitals (DMCSH) in Gojjam zones from February 1, 2017 to April 30, 2017. The first two hospitals are found in the West Gojjam zone, and the rest are found in the East Gojjam zone.

Study design and population

An institution-based unmatched case-control study was conducted among pregnant women attending ANC and admitted for delivery in obstetrics and gynaecology departments. The source populations were all pregnant women who attended ANC or delivered in Gojjam Zones. The study population was pregnant women who came to Finote Selam General Hospital (FSGH), Asrade Primary Hospital (APH), Debre Markos Comprehensive and Specialised Hospital (DMCSH), and Shegaw Motta Primary Hospitals (SMPH) for ANC or delivery during the study period. All consecutively selected pregnant women who came for ANC and were admitted for delivery during the data collection period were the sampled population.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The cases were women whose blood pressure was < 140/90 mmHg at ≥ 20 weeks’ gestation and who had proteinuria. The control groups were women whose blood pressure was < 140/90 mmHg at ≥ 20 weeks’ gestation and who did not have one or more of the above criteria for preeclampsia. Women who were unable to respond to the interview and were severely ill were excluded from the study.

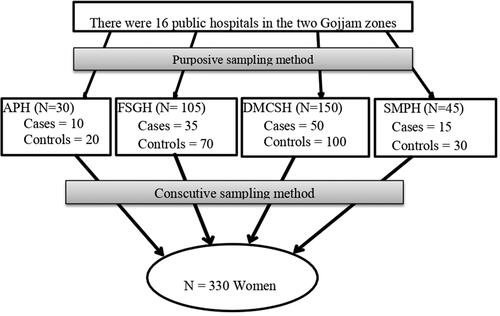

Sample size determination and sampling procedure

The sample size was calculated by using OpenEpi version 2.3 and assuming a case-control ratio of 1:2 with a significant level of 95%, a power of 80%, a proportion of hormonal contraceptive use among women without preeclampsia of 36.8% [Citation13], and a minimum detectable odds ratio of 2.0. By adding the 10% non-response rate, the final sample size = 330. The four hospitals were selected purposefully among the 16 hospitals that are found in Gojjam Zones. The cases that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were selected until the required sample size was attained. Then the next two immediate controls were selected consecutively in the same manner as cases ().

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design or conduct or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Data collection procedures

A questionnaire was prepared by reviewing different literature. Then the questionnaire was translated from English to Amharic and back to English. The data was collected through measurements and a face-to-face interview using a pretested questionnaire. The women were interviewed about their socio-demographic characteristics, medical history, obstetric factors, and behavioural factors by trained health professionals ().

The measurements included the women’s blood pressure, weight, height, and urine. Blood pressure was measured while the women were seated in an upright position using a mercury sphygmomanometer apparatus. Before taking the measurement, the participants were allowed to rest. The measurement was taken from the participant’s right hand, which covers two-thirds of the upper arm. A standard mercury sphygmomanometer was used throughout the study to minimise measurement error (instrument bias). The fruit consumption was measured using a food frequency questionnaire.

Proteinuria was assessed using the urine dipstick method, which was done as a routine investigation for all pregnant women. Urine samples were collected from pregnant women who attended ANC and sent into the laboratory rooms at the selected hospitals. Then a urine dipstick test was done after the women provided urine samples. The health care providers used a dipstick made with a colour-sensitive pad. The colour changes on the dipstick indicated the woman’s level of protein in the urine.

Data quality control

Training was given for data collectors and supervisors. A clear explanation of the purpose of the study was provided to the respondents at the beginning of the interview. Before one week of actual data collection, a pre-test was conducted to check the consistency of the questionnaire. Supervisors and the principal investigator kept close supervision over the data collection process.

Statistical analysis

After data collection, the data were coded, entered, and cleaned using EPI-info version 7 software. Then the data were exported to STATA version 14 for analysis. Descriptive analyses like frequency, mean, and standard deviation were carried out. The association between preeclampsia and each variable was checked using bivariate logistic regression. We included variables with a p value less than .05 in multivariable analysis. This was due to the excess number of eligible variables in the bivariate logistic regression analysis and in order to get the best-fit model. At the same cut-off point, variables with a p value less than .05 in the multivariate logistic regression analysis were considered significantly associated factors. Text, tables, and figures were used to present the findings.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

One hundred and ten cases and 220 controls participated in this study, yielding a 100% response rate. The mean ages of cases and controls were 28 ± 6 SD and 27 ± 5 SD years, respectively. More than half (51.8%) of the cases and 121 (55.0%) controls were in the age range of 20–29 years old. Concerning educational status, 51 (46.4%) of cases and 81 (36.8%) of controls had no formal education ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of women attended ANC and delivery.

Medical factors of preeclampsia

About 10 (9.1%) of cases and 7 (3.2%) of controls had a family history of hypertension. Similarly, 6 (8.6%) of the cases and 2 (1.7%) of the controls had a previous history of preeclampsia. Two (1.8%) of cases and two (0.9%) of controls had a family history of diabetes mellitus ().

Table 2. Distribution of medical illness factors of women attending ANC and delivery.

Obstetrics and contraceptive related factors

About 48 (43.6%) of cases and 71 (32.3%) of controls were primigravida. About 16 (14.5%) cases and 14 (6.4%) controls had multiple pregnancies. The majority of 98 (89.1%) of cases and 207 (94.1%) of controls attended ANC during their current pregnancies. Concerning the contraceptive methods, 95 (86.4%) of cases and 176 (80.0%) of controls were using contraceptives before their current pregnancy ().

Table 3. Obstetrics factors of women attended ANC and deliver service in Gojjam zones.

Behavioural factors of preeclampsia

About 87 (79.1%) of cases and 176 (80.0%) of controls drank alcohol during their pregnancies. Tella was drunk more frequently. This is a favourite traditional alcohol commonly drunk in the region. Among the participants, 89 (80.9%) cases and 181 (82.3%) controls drank coffee. About 50 (45.5%) cases and 82 (37.3%) controls consumed foods containing excess salt. Thirty-five (31.8%) of the cases and 48 (21.7%) of the controls did not eat fruit during their pregnancies. About 11 (10.0%) of cases and 8 (3.6%) of controls took traditional drugs during their current pregnancy. Nevertheless, the types of traditional drugs were not specified, so future studies would be investigated by identifying these traditional drugs.

Factors associated with preeclampsia

The factors associated with preeclampsia were identified using multivariate logistic regression analysis. The variables with a p value less than .05 in the bivariate logistic regression analysis were entered into multivariate logistic regression. In the same manner, those variables with a p value less than .05 in the multivariate logistic regression analysis were considered significantly associated factors.

There were both risk factors and preventive factors for preeclampsia. Previous use of implant contraceptives before their pregnancy and consuming fruits during their pregnancy were preventive factors for preeclampsia. But the mechanism of the previous use of implant contraceptives in preventing preeclampsia is not well understood. Hence, readers would do well to consider further studies regarding this association.

Pregnant women who had a history of abortion were 3.17 (AOR = 3.17; 95% CI: 1.31–7.70) times more likely to be exposed to preeclampsia compared with controls. Similarly, pregnant women with a history of paternity change were 3.16 (AOR = 3.6; 95% CI: 1.67–6.83) times more likely to be exposed to preeclampsia than women without a history of paternity change. In addition to this, pregnant women who had multiple pregnancies were 2.68 (AOR = 2.6; 95% CI: 1.10–6.58) times more likely to have preeclampsia as compared with controls.

In contrast, the odds of pregnant women who used implant contraceptives were 41% (AOR = 0.41; 95% CI: 0.18–0.93) higher than the odds of women without preeclampsia. This means that women who used implants before their pregnancy had a 59% reduction in their risk of being exposed to preeclampsia. In addition, pregnant women who had eaten fruit during their current pregnancy were 64% (AOR = 0.36; 95% CI: 0.18–0.72) less likely to be exposed to preeclampsia compared with women without the condition ().

Table 4. Factors associated with preeclampsia women attended ANC and delivery.

Discussion

This study was conducted, using a case-control study design, to determine the factors associated with preeclampsia among pregnant women. According to this study, history of paternity change, history of abortion, multiple gestation pregnancy, history of implant use before the current pregnancy, and intake of fruits during this pregnancy were factors associated with preeclampsia.

There was a significant association between the change of paternity and preeclampsia. This finding was in line with the previous studies [Citation14,Citation15]. The reason behind this might be that parental human leukocyte antigen sharing may have a role in the aetiology of preeclampsia [Citation16]. The immunological maladaptation at the foetal-maternal interface may be the root cause. Many epidemiological studies revealed that some fathers might have genetic predispositions when it comes to successful placentation, sometimes referred to as the dangerous father hypothesis [Citation17]. However, there are paradoxical ideas between studies about this association. For example, according to a study conducted in Sweden, changes in partners were associated with a protective effect against preeclampsia in the recurrence of births of small gestational age. Contrarily, partner change was associated with a higher risk of small for gestational age in second pregnancies among women who had no history of small for gestational age in their first pregnancy. Changes in partners had no impact on the chances of preeclampsia during term pregnancy [Citation18,Citation19].

In this study, the history of abortion was a risk factor for preeclampsia. The finding was comparable with a study done in Thailand [Citation20]. The current finding was also consistent with a study conducted in Tahran, Iran, where a history of spontaneous abortion increases the occurrence of preeclampsia during a subsequent pregnancy [Citation21]. However, the finding was inconsistent with a study conducted in New Haven, USA, and China in which the history of abortion reduces the risk of preeclampsia in a subsequent pregnancy among nulliparous women [Citation17,Citation22]. A recent case-control study in Sudan showed that preeclampsia risk was lower in women with a history of spontaneous abortion than in women without such a history [Citation23]. The differences may be that in our study, the type of previous abortion was not specified. This means we did not differentiate whether the previous abortion was spontaneous or induced. In contrast, the study conducted in Sudan was specified as spontaneous. In addition to this, the controversy might be due to the fact that the women were nulliparous in the study conducted in Sudan, but in our study, we included women with all types of parities. Women with a history of abortion have already gone through changes in their hormone and immune systems during pregnancy.

The odds of multiple gestational pregnancies were higher among women with preeclampsia compared with women without preeclampsia. This was consistent with a study done in Thailand and Uganda [Citation20,Citation24]. The possible reason might be due to greater trophoblastic volume and foetal antigen load and the large placental size, which leads to impaired placental perfusion [Citation25,Citation26]. However, there was no association in a study done in Brazil [Citation27].

Concerning contraceptive use, the odds of previous use of implants were 0.41 among women with preeclampsia compared with controls. This finding was in line with a study done in Thailand [Citation20]. The combined hormonal contraceptive has an effect on vascular resistance due to the presence of oestrogen. This, in turn, increases blood pressure. On the contrary, implant contraceptives do not contain oestrogen as an ingredient. The mechanism of association between previous use of implant contraceptives and preeclampsia is not well understood. Therefore, we could not indicate the mechanism by which previous use of implants could prevent preeclampsia. However, no significant association was observed in a study conducted in China [Citation28]. This result variation may be due to a difference in data sources and race. In addition to this, the differences might be due to variation in the data sources and nature of the study design, non-specificity of the outcome variable and socioeconomic and lifestyle differences between these countries.

Regarding behavioural factors, pregnant women who were using fruits during their current pregnancy were 64% more likely to be exposed to preeclampsia as compared with controls. The result was consistent with case-control studies conducted in Egypt and Indonesia [Citation29,Citation30]. The reason behind this association might be that vegetables and fruits are rich in micronutrients such as antioxidants, vitamins, minerals, and dietary fibre that decrease the risk of hyperhomocysteinemia, which is one of the risk factors for the occurrence of preeclampsia. This condition, in turn, reduces the risk of being exposed to preeclampsia.

Strengths and limitation of the study

The strength of the study is its strong design and use of primary data for research. As a limitation, recall bias might be introduced since women with preeclampsia may remember the events more than women without the condition.

Conclusions

A previous history of abortion, a change in paternity, and multiple gestational pregnancies were risk factors for preeclampsia. Previous use of implant contraceptives and the consumption of fruit during their pregnancy were protective factors against preeclampsia. Healthcare providers should give special attention to women with a history of abortion and multiple gestational pregnancies during the ANC follow-up period. To examine the underlying mechanisms of previous implant contraceptive use and abortion on the development of preeclampsia, more researches should be conducted.

Authors contributions

AWA, AWT: Participated in conception, design, proposal writing, data collection, and data analysis, interpretation of the result, and manuscript drafting and write-up. AWA, AA: Conducted the formal analysis, critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics statement

Addis Ababa University School of Public Health Institutional Review Board provided an ethical clearance letter with an ethical number of SPH/001/2017. An informed consent was obtained from each respondent after explaining the purpose of the study. The confidentiality and privacy of the respondents’ responses were secured.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (431.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the study participants and data collectors.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that non-financial associations that may be relevant to the submitted manuscript.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository in Addis Ababa University.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Jim B, Sharma S, Kebede T, et al. Hypertension in pregnancy: comprehensive update. Cardiol Rev. 2010;18(4):1–8. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181c60ca6.

- Jeyabalan A. Epidemiology of preeclampsia: impact of obesity. Nutr Rev. 2013;71(1):S18–S25.

- Duley L. Maternal mortality associated with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99(7):547–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13818.x.

- Magee LA, Brown MA, Hall DR, et al. The 2021 international society for the study of hypertension in pregnancy classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022;27:148–169. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2021.09.008.

- Dekker G, Sibai B. Primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of preeclampsia. Lancet. 2001;357(9251):209–215. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03599-6.

- Onakewhor JU, Gharoro EP. Changing trends in maternal mortality in a developing country. Niger J Clin Pract. 2008;11(2):111–120.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. Health sector development program IV (2010/11–2014/15). 2010.

- Wolde Z, Segni H, Woldie M. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in Jimma university specialized hospital. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2011;21(3):147–154.

- Shey Wiysonge CU, Ngu Blackett K, Mbuagbaw JN. Risk factors and complications of hypertension in Yaounde, Cameroon. Cardiovasc J S Afr. 2004;15(5):215–219.

- Mills JL, Klebanoff MA, Graubard BI, et al. Barrier contraceptive methods and preeclampsia. JAMA. 1991;265(1):70–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.1991.03460010070033.

- Ness RB, Markovic N, Harger G, et al. Barrier methods, length of preconception intercourse, and preeclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2004;23(3):227–235. doi: 10.1081/PRG-200030293.

- Tesfa E, Nibret E, Gizaw T, et al. Prevalence and determinants of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2020;15(9):e0239048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239048.

- Central Statistical Agency. Ethiopia mini demographic and health survey. Ethiopia: Addis Ababa; 2014.

- Endeshaw M, Ambaw F, Aragaw A, et al. Effect of maternal nutrition and dietary habits on preeclampsia: a case-control study. IJCM. 2014;05(21):1405–1416. doi: 10.4236/ijcm.2014.521179.

- Galaviz-Hernandez C, Sosa-Macias M, Teran E, et al. Paternal determinants in preeclampsia. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1870. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01870.

- El-Moselhy EA, Khalifa HO, Amer SM, et al. Risk factors and impacts of pre-eclampsia: an epidemiological study among pregnant mothers in Cairo, Egypt. J Am Sci. 2011;7(5):311–323.

- Eras JL, Saftlas AF, Triche E, et al. Abortion and its effect on risk of preeclampsia and transient hypertension. Epidemiology. 2000;11(1):36–43. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200001000-00009.

- Wikström A-K, Gunnarsdóttir J, Cnattingius S, et al. The paternal role in pre-eclampsia and giving birth to a small for gestational age infant; a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(4):e001178. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001178.

- Cnattingius S, Wikström AK, Stephansson O, et al. The impact of small for gestational age births in early and late preeclamptic pregnancies for preeclampsia recurrence: a cohort study of successive pregnancies in Sweden. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2016;30(6):563–570. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12317.

- Manandhar BL, Chongstuvivatwong V, Geater A. Antenatal care and severe pre-eclampsia in Kathmandu valley. J Chitwan Med Coll. 2014;3(4):43–47. doi: 10.3126/jcmc.v3i4.9554.

- Sepidarkish M, Almasi-Hashiani A, Maroufizadeh S, et al. Association between previous spontaneous abortion and pre-eclampsia during a subsequent pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;136(1):83–86. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12008.

- Su Y, Xie X, Zhou Y, et al. Association of induced abortion with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy risk among nulliparous women in China: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):5128. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61827-0.

- Mohamedain A, Rayis DA, AlHabardi N, et al. Association between previous spontaneous abortion and preeclampsia: a case–control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):715. doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-05053-8.

- Kiondo P, Wamuyu-Maina G, Bimenya GS, et al. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia in Mulago hospital, Kampala, Uganda. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17(4):480–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02926.x.

- Sibai B. Immunologic aspects of preeclampsia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1991;34(1):27–34. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199103000-00007.

- Broughton Pipkin F. Risk factors for preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(12):925–926. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103223441209.

- Dantas E, M, D, Pereira FVM, Queiroz, et al. Preeclampsia is associated with increased maternal body weight in a northeastern Brazilian population. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:159. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-159.

- Ye C, Ruan Y, Zou L, et al. Survey on hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) in China: prevalence, risk factors, complications, pregnancy and perinatal outcomes. PLOS One. 2014;9(6):e100180. 17doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100180.

- Farley KE, Huber LR, Warren-Findlow J, et al. The association between contraceptive use at the time of conception and hypertensive disorders during pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study of prams participants. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(8):1779–1785. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1447-6.

- Kartasurya MI. Pre-eclampsia risk factors of pregnant women in semarang, Indonesia. IJSBAR. 2015;22(1):31–37.