Abstract

Purpose

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is one of the leading causes of death in women, largely underpinned by hypertension. Current guidelines recommend first-line therapy with a RAAS-blocking agent especially in young people. There are well documented sex disparities in CVD outcomes and management. We evaluate the management of patients with newly diagnosed hypertension in a tertiary care clinic to assess male–female differences in investigation and treatment.

Methods

Clinic letters of all new patients under the age of 51 attending the Glasgow Blood Pressure Clinic between January and December 2023 were reviewed. The primary outcomes measured were first-line treatment choices, deviations from guideline-recommended treatment, investigations for secondary hypertension, and documentation of female-specific risk factors and family planning advice. Secondary outcomes included clinical characteristics such as systolic and diastolic blood pressure at referral and at the new patient appointment, age at diagnosis, age at first appointment, and the number of antihypertensive drugs prescribed at referral.

Results

One hundred and five (59:46, M:F) new patient encounters were reviewed after sixteen exclusions for non-attendance and inappropriate clinic coding. Choice of first line antihypertensive agent did not vary between sexes with no deviation from guideline-recommended medical therapy. Men, however, had more biochemical investigations conducted for secondary causes across all ages. This was greatest in those under 40 years old. There was suboptimal documentation of female-specific risk factors (obstetric and gynaecological history), contraceptive drug history and family planning with 35%, 20%, and 15.6%, respectively.

Conclusion

In 2023, women under 51 years of age seen in a tertiary care hypertension clinic received similar first-line treatment to their male peers. However, relevant female-specific histories were suboptimally documented for these patients. Whilst therapeutic approaches in men and women appear to be similar in this clinic, there are opportunities to improve CVD prevention in women, even in a specialised clinic setting.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Hypertension, or persistent high blood pressure, is a condition that can lead to serious cardiovascular diseases such as stroke and heart failure. Evidence has shown that women have cardiovascular disease more than men and it is the leading cause of death in women in Europe. To understand how male and female patients are treated for hypertension, we examined documented consultations and treatments of 105 patients under the age of 51 (46 women and 59 men) at a Glasgow hypertension clinic in 2023. We found that men had more investigations for specific causes of their hypertension across all ages (men = 88%, women = 61%). Recording of reproductive history (35%), contraceptive drug history (20%) and advice on family planning (15.6%) was not as thorough as they could be. Incorrect management of female reproductive history and contraceptive drug history can increase the risk of long-term hypertension complications, so managing this is crucial. A class of drugs commonly used to manage hypertension called RAAS blockers are dangerous to the foetus when pregnant - another factor to consider when managing young women with high blood pressure. Overall, these findings mean that there may be a need for more thorough consideration of women’s health factors in hypertension treatment. By paying attention to these areas, we can enhance long-term cardiovascular health for women.

Introduction

Traditionally, cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been regarded as a disease predominantly affecting men, with modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. However, CVD is the leading cause of death in women worldwide [Citation1]. While there has been an improvement in cardiovascular health globally over the past three decades, the subgroup in which there has been minimal improvement since the early 2000s are premenopausal women [Citation2]. Hypertension is a key underpinning factor of CVD and optimal blood pressure management reduces all major adverse cardiovascular events [Citation3].

There are female-specific CVD risk factors that should be assessed, documented and where possible, targeted, such as polycystic ovarian syndrome, early menarche and early menopause and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy including, but not exclusively, pre-eclampsia [Citation4]. This recommendation is supported by guidelines that primarily address hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, history of contraceptive use, and contraindications to antihypertensive drugs. However, these guidelines often overlook other sex-specific aspects such as diagnosis and follow-up processes. Moreover, it has been shown that female CVD risk is frequently under-recognised by physicians, despite existing guidelines [Citation4, Citation5]. Comprehensive documentation of female-specific risk factors would allow for optimal first line management, for instance by avoiding teratogenic antihypertensives in women of childbearing potential, and more effective long-term risk stratification and surveillance. A Canadian study found that inadequate documentation of non-sex specific cardiac risk factors such as smoking and diabetes in hospitalisations for myocardial infarction hindered the optimisation of patient care [Citation6]. It has been further recognised that women experience suboptimal management of conventional risk factors compared to men [Citation7] which further complicates the aforementioned challenges.

Current European Society of Hypertension (ESH) guidance recommends the initiation of two-drug therapy comprising of a RAAS blocker with a calcium channel blocker (CCB) or thiazide diuretic [Citation3]. Due to a lack of data, the guidelines do not include age-specific or sex-specific differences in regimens at first presentation or overall. Previous literature has described that there may be a disparity in the number of men and women prescribed ACE inhibitors (ACEis) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) due to their teratogenic effects, even when the patient is not pregnant or planning pregnancy [Citation8]. Additionally, those diagnosed under the age of 40 are more likely to have a secondary cause of hypertension [Citation9], compounding the importance of recording relevant history, examination and investigations of secondary causes.

Using documented clinic data from first presentations to the Glasgow Blood Pressure Clinic over 11 months in 2023, this study explores sex specific disparities in first-line treatment choices, deviations from guideline-recommended treatment, and investigations for secondary hypertension, with the aim of elucidating the potential causes for any sex disparities and proposing changes in practice to improve these. For the purposes of this work, young is defined as under the age of 51 as it is the average age of the menopause in the UK [Citation10].

Methods

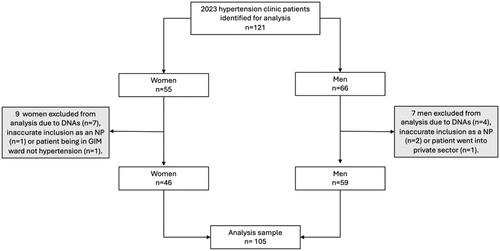

A retrospective review of electronic records and clinic letters processed between 1st January and 1st December 2023 at the Glasgow Blood Pressure Clinic was conducted. This is a tertiary referral clinic within NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde. New referrals of patients with hypertension were identified using the electronic clinic booking system. All new patients under the age of 51 attending the clinic between the aforementioned dates were included in the study (n = 121, ). By focusing on referrals from the year 2023, we aimed to provide a current picture of clinical practices and outcomes in hypertension management at a tertiary clinic that time and allows for a more accurate assessment of recent trends in practices that may be applied elsewhere.

Figure 1. Selection and inclusion/exclusion of patients.

Flowchart demonstrating the exclusions made during the analysis based on various criteria such as failure to attend appointments resulting in DNA (Did Not Attend), inaccurate coding as a new patient (NP) and other specified reasons.

Referrals arose predominantly from primary care, with a smaller number arising from acute hospital admissions. Referrals, submitted electronically via the Scottish Care Information (SCI) system, varied in detail from comprehensive histories with multiple BP readings and risk factors to simpler entries. Sixteen patients were excluded from the cohort due to clinic non-attendance or inappropriate clinic coding as a new patient (). Therefore, a total of 105 patients were analysed. Data were gathered from the referral letter to clinic and the clinic appointment letter at their first visit. All data were anonymised and collected in an encrypted spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel. Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarise continuous variables. Proportions between male and female groups were investigated using Chi-squared and z-tests for proportions. A significance level of p < 0.05 was chosen for all statistical inferential tests. All data were analysed using RStudio version 4.3.1 (2023-06-16).

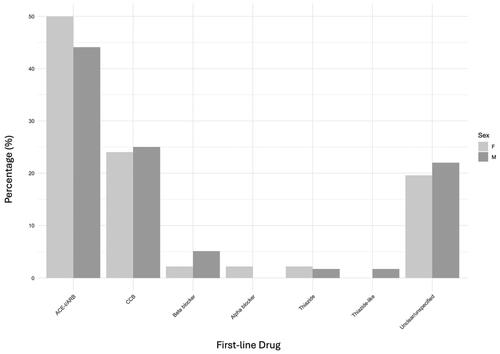

Figure 2. Distribution of patients based on gender and first-line drug.

Each bar represents the percentage (%) of males (M) and females (F) given each drug as a percentage of the total first-line drugs given within each male/female category. ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker.

Ethics statement

This is a clinical audit and is therefore exempt from formal ethical approval. The audit proposal has, however, been presented to the Glasgow Blood Pressure Clinic Multidisciplinary Team and was approved.

Results

Characteristics of the patient cohort

Data was collected from 105 patients (46 women and 59 men) with an age range from 21 to 51 years. The mean male age was 34.8 and mean female age was 33.9 at diagnosis and 37.4 and 35.6, respectively at their first appointment. At their new patient appointment at the hypertension clinic, men had an average blood pressure (BP) of 145/93 mmHg and women 137/90 mmHg ().

Table 1. Characteristics of new patients under the age of 51 attending hypertension clinic for the first time.

Of the 105 hypertensive patients, 34 were well controlled in primary care by the time they reached their first appointment in the specialist clinic (BP of <140/90 mmHg). 13 (12.4%) patients had a pre-existing diagnosis of hypertension before their initial appointment as new patients in 2023. This could be attributed to recent relocation or previous management by primary care, either within our clinic or elsewhere in preceding years. Men and women were on an average of 1.66 and 1.26 antihypertensive agents, respectively at the time of first assessment at the hypertension clinic ().

First line treatment

Regarding first line treatment choices, 50% of women and 44% of men were prescribed an ACEi or ARB with no significant difference in first-line management between sexes (p = 0.55) ( and ).

Table 2. First-line treatment of male and female new patients at time of first attendance at the hypertension clinic.

CCBs were given second most commonly after RAAS blockers (). Less than 5% of total patients were treated with a thiazide, thiazide-like diuretic or an alpha blocker. In 20% of patients, it could not be identified what their first medication was as they were on more than one medication at the time of first review.

There was no significant difference found between men and women commencing guideline-recommended treatment as a first line treatment (). 29% of men and 35% of women were prescribed other medication as first line antihypertensive (p = 0.45). Additionally, there was no difference between men and women in documentation of a clinical explanation (41% and 38%, respectively, p = 0.71) for any deviation prescribed. However, the percentage of patients with documented explanation of deviations in treatment was low (<42%) for both men and women.

Table 3. Percentage of male and female patients with treatment deviation from guideline-recommended first line treatment.

Secondary hypertension investigation

Investigations typically conducted in the hypertension clinic are serum cortisol levels, serum metadrenaline levels, renin and aldosterone concentrations and urinary catecholamine and cortisol levels. In the study population, men had a significantly higher rates of investigation of secondary causes; 88% of men compared to 61% of women (p < 0.001). Urine biochemistry was, however, done in similar percentages in men (39%) and women (39%; p = n.s.) ().

Table 4. Percentage of male and female patients with secondary hypertension investigations.

In patients under the age of 40 years, men were investigated more frequently for serum markers of secondary causes of hypertension than women (p = 0.008). However, women more frequently underwent urine biochemistry tests than men (p = 0.002) ().

Female specific risk factor documentation & family planning advice

In clinic letters, 36% of women had their obstetrics and gynaecology history documented. 20% of women on antihypertensive medication had their contraceptive drug history documented. 16% of women were given family planning advice. The percentage of women given an ACE inhibitor or ARB as a first-line treatment who were also given family planning advice was 29%. Overall, 7% of women had all three of these aspects of clinical evaluation documented ().

Table 5. Documentation of female risk factors, family planning (FP) advice and contraception in female patients at the hypertension clinic.

Discussion

In an era where CVD is the most prevalent cause of death in all European women [Citation11], optimising the management of female patients with hypertension is of paramount importance for patients’ long-term outcomes. The data presented here demonstrates similar guideline-recommended treatment between men and women but more frequent investigations into secondary causes of hypertension in men than in women. Patients under the age of 40 have an increased likelihood of secondary causes of hypertension and as such should be investigated accordingly. Additionally, it is recommended that women of child-bearing potential should have secondary causes of hypertension investigated prior to conception [Citation3]. When assessing female specific cardiovascular risk factors, there was incomplete documentation of obstetric and gynaecological history, family planning advice and history of contraceptive drug use.

This suboptimal documentation mirrors previous studies and audits in Ireland and Oman [Citation12, Citation13]; indicating that this is not a unique situation in this clinic. Research by Zhao et al. suggests that women may receive fewer prescription medications for cardiovascular disease than men, highlighting potential disparities in treatment [Citation14]. In our clinic the prescription rate of RAAS blocking agents (ACEis and ARBs) was not significantly lower in women than in men, indicating equitable treatment across sexes. However, the percentage of women on RAAS blocking agents who were given documented advice on family planning or history of contraception use is low in our study.

Sex disparities in hypertension risk factors have been extensively documented. There are multiple studies that suggest women have different cardiovascular physiology than men [Citation15, Citation16] and this has an impact on the cardiovascular disease phenotype and the clinical presentations seen in female patients [Citation17]. Hypertension, particularly prevalent in black women, is the most common disorder of pregnancy, with implications for long-term hypertension risk [Citation18]; highlighting the importance of obtaining an obstetric history. Sex disparities also exist in other aspects of cardiovascular risk management, with women more likely being obese and having hyperlipidaemia than men but being less likely to be prescribed statins and RAAS blocking agents [Citation19]. While we cannot fully explain the observed difference in secondary hypertension assessments between men and women, it may be that the variability in blood pressure (with men on average having a higher systolic blood pressure) prompts further investigations. Furthermore, the types of investigations conducted and documented may account for some of the difference. Prior investigations such as abdominal ultrasounds done for other reasons might not have been captured in our data.

This study also found a trend that on average, men were older than females at their first appointment in the tertiary referral clinic, but age at diagnosis was similar. Speculatively, it may indicate that primary care colleagues investigate secondary causes of hypertension in women more promptly or comprehensively than in men. Therefore, further research into diagnostic practices across sexes is warranted to determine the underlying factors contributing to this observed difference.

Addressing the findings in this study has the potential to significantly improve patient care. Studies have shown that both primary care physicians and cardiologists feel underprepared in the evaluation of female specific cardiovascular risk factors [Citation4]. This could be due to the lack of incorporation of female specific risk factors into risk prediction models, as when obstetric and gynaecological patient factors are incorporated, existing models become more accurate for women [Citation20]. Additionally, it is recognised that guidelines are not necessarily easy to implement nor are they universally followed. While incorporating female-specific factors into clinical guidelines and risk prediction models has been shown to improve accuracy for women, it may add complexity to diagnosis and management which could in hand further exacerbate this issue of decreased adherence. Therefore, it may be beneficial to accompany the enhanced guidelines with comprehensive training and decision aids such as simplified integration of these factors into electronic health records. These strategies have previously been shown to improve patient outcomes [21]. With appropriate strategies adherence could potentially be improved and ultimately lead to better long-term outcomes for women.

We recognise that a standardised form for recording this information may be the most effective and realistic approach to ensure consistent and accurate documentation of female-specific factors. For example, a simple check box that asks the clinician ‘could this patient be pregnant or trying to conceive?’ in the clinic letter proforma. Furthermore, data collection through such a form would have the potential to provide consistent and easily accessible data for research and further evaluation which may play a role in refining guidelines and care in the future.

The recently updated ESH guidelines include recommendations for the use of simple protocols in combination with lifestyle counselling involving a knowledgeable, patient centred health care team and up-to-date information systems in tracking and conducting case management [22]. These factors may help positively modify the management of hypertension in premenopausal women and have the potential to improve adherence to guidelines.

Limitations of this work

First, this study is limited in scale. The tertiary clinic analysed is restricted to one half of the city of Glasgow. The statistical analysis was likely underpowered, which reflects the small numbers in our review of data from one year of new patients at their first clinic attendance. Some patients arrived at their first blood pressure clinic appointment already on therapy initiated by general practitioners or other specialists. This explains the improvement in blood pressure between time of referral and time of first review (). However, as some patients had a long-standing diagnosis managed elsewhere prior to their first review at this clinic, there were 22% of men and 20% of women where it could not be established what their historic first line drug therapy was (). While it is not necessarily a limitation for patients to have been managed in primary care, it does emphasise the importance of conducting comprehensive risk assessments and potentially reassessing management strategies during their appointment. Referrals were submitting electronically in free-text form and varied in detail, with the only mandatory field being blood pressure, meaning that some information was inconsistently reported. Ensuring that patients’ histories are thoroughly reviewed, and treatment plans are adjusted as needed can optimise the effectiveness of care provided in the clinic setting. Additionally, as this is a retrospective audit of electronic records, the conclusions are entirely dependent upon what has been documented rather than prospectively documenting a potentially more accurate version of the consultation at the time. It is well possible that some of the missing documentation and missing investigations have been done in other settings and were therefore not repeated or documented again in the clinic.

Additionally, the setting of this study in a single tertiary care clinic does limit the generalisability of the findings to other clinical environments such as primary and secondary referral clinics, so there may be a need for broader studies across these settings to better understand and address these disparities. While adherence to guideline-recommended first-line treatments was observed in this study, this may not be representative of first and secondary referral clinics.

Another limitation is that other secondary tests routinely done were not captured as part of this analysis, for example, renal ultrasound, MR angiography and other imaging studies such an echocardiography. The secondary tests that were recorded for this investigation were blood renin and aldosterone levels, with or without cortisol, as well as 24-hour urinary catecholamines, with or without cortisol. Imaging studies were not included in this assessment; the focus was solely on determining which patients underwent these initial blood tests following their referral to the hypertension service. As such, we did not assess whether there were differences in the types or frequency of these tests between men and women. These tests are often only done when prior less invasive and less costly investigations have not provided sufficient information, or clinical presentation raised suspicions that requires these tests. However, screening for aldosterone:renin ratio is the very minimum test for investigation of renovascular hypertension and primary aldosteronism; as such we have taken this as a surrogate in this study.

Conclusion

The work presented here shows that there is disparity in the investigation of secondary causes of hypertension between men and women. When assessing female specific cardiovascular risk factors, there was incomplete documentation of obstetric and gynaecological history. Family planning and contraceptive drug history was often not documented. If these gaps in documentation and the disparity in investigations into secondary cause of hypertension represent the discussions during the consultations, it may indicate missed opportunities for risk assessments and personalised management. Therefore, this may have effects on long-term health outcomes in women. Our data has also shown that there may be a disparity in primary and secondary referral patterns between sexes, with men being older at their first tertiary appointment despite no difference in age at diagnosis, suggesting that women may be receiving more timely or comprehensive investigations in primary care settings. Further research in these settings may be useful to explore these diagnostic practices and their impact on patient outcomes.

Our retrospective study has many limitations but highlights a significant gap in consultation and documentation even in a specialised tertiary hypertension clinic. A structured approach to fill these gaps including a pre-appointment survey and better use of standardised electronic assessment forms will be developed to further improve the quality of our services. We encourage colleagues in other clinical settings to look into their own practice too as even in presumably excellent services there is always room for improvement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be provided by the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Woodward M. Cardiovascular disease and the female disadvantage. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(7):1165. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/16/7/1165/htm doi: 10.3390/ijerph16071165.

- Eberly LA, Rusingiza E, Park PH, et al. Nurse-driven echocardiography and management of heart failure at District Hospitals in Rural Rwanda. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(12):e004881. doi: 10.1161/circoutcomes.118.004881.

- Mancia G, Kreutz R, Brunström M, et al. 2023 ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA). J Hypertens. 2023;41(12):1874–2071. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000003480.Erratum in: J Hypertens. 2024 Jan 1;42(1):194.

- Isakadze N, Mehta PK, Law K, et al. Addressing the gap in physician preparedness to assess cardiovascular risk in women: a comprehensive approach to cardiovascular risk assessment in women. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2019;21(9):47. doi: 10.1007/s11936-019-0753-0.

- Burnier M, Brguljan J, Algharably EAE, et al. Women’s health, cardiovascular risk and hypertension: the perspective still needs to improve. Blood Press. 2023;32(1):2193648. doi: 10.1080/08037051.2023.2193648.

- Cox JL, Zitner D, Courtney KD, et al. Undocumented patient information: an impediment to quality of care. Am J Med. 2003;114(3):211–216. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01481-X.

- Driscoll A, Beauchamp A, Lyubomirsky G, et al. Suboptimal management of cardiovascular risk factors in coronary heart disease patients in primary care occurs particularly in women. Intern Med J. 2011;41(10):730–736. Oct doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02534.x.

- Ferrannini G, De Bacquer D, Vynckier P, et al. Gender differences in screening for glucose perturbations, cardiovascular risk factor management and prognosis in patients with dysglycaemia and coronary artery disease: results from the ESC-EORP EUROASPIRE surveys. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12933-021-01233-6.

- Charles L, Triscott J, Dobbs B. Secondary hypertension: Discovering the underlying cause. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(7):453–461. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29094913/

- NHS inform. Menopause [Internet]. NHS Inform; 2024. Available from: https://www.nhsinform.scot/menopause.

- European Heart Network and European Society of Cardiology. European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics. 2012. Available from: https://www.escardio.org/static-file/Escardio/Press-media/press-releases/2013/EU-cardiovascular-disease-statistics-2012.pdf.

- Al-Shidhani TA, Bhargava K, Rizvi S. An audit of hypertension at University Health Center in Oman. Oman Med J. 2011;26(4):248–252. doi: 10.5001/omj.2011.60.

- Meagher PF, Deery C, Linton AF, et al. An audit of hypertensive care in general practice. Ir Med J. 1993;86(1):20–22. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8444586/

- Zhao M, Woodward M, Vaartjes I, et al. Sex differences in cardiovascular medication prescription in primary care: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(11):e014742. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014742.

- Lau ES, Paniagua SM, Guseh JS, et al. Sex differences in circulating biomarkers of cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(12):1543–1553. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.06.077.

- Yahagi K, Davis HR, Arbustini E, et al. Sex differences in coronary artery disease: pathological observations. Atherosclerosis. 2015;239(1):260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.01.017.

- Garcia M, Mulvagh SL, Bairey Merz CN, et al. Cardiovascular disease in women. Circ Res. 2016;118(8):1273–1293. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307547.

- Minhas AS, Ogunwole SM, Vaught AJ, et al. Racial disparities in cardiovascular complications with pregnancy-induced hypertension in the United States. Hypertension. 2021;78(2):480–488. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17104.

- Wright AK, Kontopantelis E, Emsley R, et al. Cardiovascular risk and risk factor management in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2019;139(24):2742–2753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.039100.

- Tschiderer L, Seekircher L, Willeit P, et al. Assessment of cardiovascular risk in women: progress so far and progress to come. Int J Womens Health. 2023;15:191–212. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S364012.

- Kwan JL, Lo L, Ferguson J, et al. Computerised clinical decision support systems and absolute improvements in care: meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2020;370:m3216. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3216.

- Whelton PK, Flack JM, Jennings GL, et al. Editors’ commentary on the 2023 ESH management of arterial hypertension guidelines. AHA J. 2023;80(9):1795–1799. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.123.21592.