Abstract

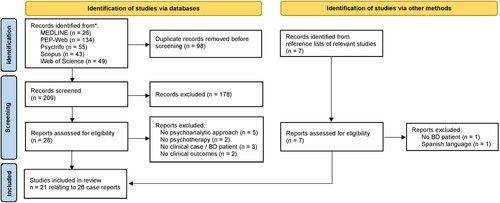

No systematic review has been conducted to provide an overview of the effectiveness of psychoanalysis for treatment outcomes in bipolar depression and mania. The present study undertakes a scoping review of the effectiveness of psychoanalysis for bipolar disorder (BD), provides a summary of the evidence base, and identifies issues for future research in this area. A thorough search of journal articles in MEDLINE, PEP-Web, PsycINFO, Scopus, and the Web of Science was carried out to obtain available studies on psychoanalytic treatment for BD published from 1990 to 2021. We searched for either quantitative or single-case studies. Twenty-six single-case reports from 21 articles and no quantitative studies met the inclusion criteria. A qualitative analysis suggests efficacy and cost-effectiveness but thus far there is no scientific evidence in support of psychoanalysis. Although these pilot findings suggest that psychoanalysis may impact symptoms and global functioning in individuals with BD, the underlying evidence is poor and should be confirmed by experimental studies.

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a lifelong illness characterized by severe and persistent fluctuations in mood state and energy, resulting in psychological distress and behavioral impairment (Carvalho, Firth, & Vieta, Citation2020; Grande, Berk, Birmaher, & Vieta, Citation2016). Although its onset can be in childhood (Youngstrom, Birmaher, & Findling, Citation2008), it usually begins in adolescence (Youngstrom, Morton, & Murray, Citation2020b) and it affects around 1–4% of the world’s population (Moreira, Van Meter, Genzlinger, & Youngstrom, Citation2017; Vieta et al., Citation2018). The course of the illness is variable but it often results in cognitive and functional impairments, increased mortality, and, more generally, reduced quality of life (Carvalho et al., Citation2020; Grande et al., Citation2016; Youngstrom et al., Citation2020a). Indeed, BD is ranked among the 20 leading causes of disability among all injuries and acute/chronic diseases worldwide (Vos et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, individuals with BD are at high risk of developing chronic medical conditions (De Hert et al., Citation2011; Stefana et al., Citation2020) as well as of dying by suicide (a 20/30-fold higher risk than in the general population) (Malhi et al., Citation2015; Plans et al., Citation2019). Identifying the most effective forms of treatment is therefore a global health priority.

At present, pharmacotherapy represents the first-line treatment option (Yatham et al., Citation2018). However, despite the effectiveness of medications in helping those with BD to recover from acute depressive or manic episodes, drugs alone do not enable many of these patients to significantly improve their post-episode symptoms, or achieve a satisfactory functional recovery, or prevent illness recurrences (Cipriani et al., Citation2009, Citation2011, Citation2016; Correll, Sheridan, & DelBello, Citation2010; Goodwin et al., Citation2016; Pacchiarotti et al., Citation2013; Yatham et al., Citation2018).

Optimal long-term management combines medications with psychosocial interventions, including psychotherapy and lifestyle approaches (Geddes & Miklowitz, Citation2013). Indeed, there is evidence that psychological interventions are effective for adults with BD (Oud et al., Citation2016), especially when combined with pharmacotherapy or psychoeducation (Chatterton, Stockings, Berk, Barendregt, Carter, & Mihalopoulos, Citation2017; Miklowitz et al., Citation2006), and are capable of producing the behavioral and lifestyle changes crucial for preventing relapses and maintaining positive function (vs. simple symptom reduction) (Frank, Citation2007; Frank et al., Citation2014; Miklowitz et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, it should be noted that although considerable progress has been made in understanding, managing, and treating BD in recent decades, we are still far from a personalized psychiatric approach to this disorder that allows precisely optimized biological and psychosocial interventions (Grande et al., Citation2016; Kalin, Citation2020).The treatment of these patients remains, in the main, a subjective clinical exercise (Carvalho et al., Citation2020).

Several therapies have growing and positive evidence bases for effectiveness in terms of improving symptoms, social functioning, and/or risk of relapse; these include cognitive-behavioral therapy (Chiang, Tsai, Liu, Lin, Chiu, & Chou, Citation2017; Ye et al., Citation2016), psychoeducation (Colom et al., Citation2003), interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (Lam & Chung, Citation2021), mindfulness-based and mindfulness-informed interventions (Burgos-Julián, Ruiz-Íñiguez, Peña-Ibáñez, Montero, & Santed-Germán, Citation2022; Xuan et al., Citation2020), functional remediation (Torrent et al., Citation2013), group therapy (Janis, Burlingame, Svien, Jensen, & Lundgreen, Citation2021), and also psychodynamic therapies (Abbass, Town, Johansson, Lahti, & Kisely, Citation2019; Caldiroli et al., Citation2020). Psychoanalytic methods are the oldest on this list, but are relatively less studied for bipolar disorder (Stefana et al., Citationunder review). Psychodynamic therapies derived from classical psychoanalysis may be equally as effective as other forms of evidence-based psychotherapy for common mental disorders (Steinert, Munder, Rabung, Hoyer, & Leichsenring, Citation2017), including both unipolar and bipolar (Caldiroli et al., Citation2020) depression. More generally, long-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy has been shown to be useful in improving the long-term outcome of chronic (Leuzinger-Bohleber et al., Citation2019) and treatment-resistant (Fonagy et al., Citation2015) depression. However, to date, no systematic review has been conducted that focuses specifically on psychoanalytic treatment for BD.

Here it should be noted that psychoanalysis and long-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy can be placed on a continuum: according to a large number of theoretical and practicing psychoanalysts, separating them (usually based on extrinsic criteria such as the weekly frequency of sessions or the use of face-to-face therapy as opposed to use of the couch) is a false problem (Stefana, Celentani, Dimitrijevic, Migone, & Albasi, Citation2022).

Historically, psychoanalysis traces its origins back to the beginning of the twentieth century. It quickly became firmly entrenched in European culture due to Sigmund Freud’s success in keeping up with the natural sciences of his time and integrating psychoanalysis with various trends in psychology, biology, physiology, and psychophysics (Makari, Citation2008). In defining psychoanalysis, Freud (Freud, Citation1989) distinguished three interrelated levels: a method of investigation of human functioning, a complex of psychological and psychopathological theories, and a method of treatment. Today the psychoanalytic model is unique in contributing a developmental theory (of attachment relationships) strongly supported by empirical evidence and is useful in understanding the relationship between early experience, genetic inheritance, and the development of subjectivity as well as psychopathology (Cassidy & Shaver, Citation2018; Fonagy & Lemma, Citation2012; Harari & Grant, Citation2022).

The fundamental principles that guide the psychoanalytic approach are: (1) the existence of the unconscious and its central role in mental life; (2) the implications/consequences of the interaction between childhood experiences and genetic factors in shaping the development of the individual; (3) the idea that symptoms and behaviors are determined by a complex of biological and unconscious factors; (4) transference as a primary source of understanding the personality characteristics and psychopathology of the patient; (5) countertransference as a ‘technical tool’ potentially able to provide valuable information about what happens in the relationship with the patient; (6) the analysis of the patient’s resistance to therapy; and (7) the facilitation/support of the patient to achieve a sense of authenticity (Gabbard, Citation2017). The aspects embodied in these principles that jointly determine the very essence of psychoanalytic technique are technical neutrality, transference analysis, interpretation, and countertransference analysis. Notably, some of the theoretical and technical features typical of the psychoanalytic approach have been adopted by other modalities, particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy (Fonagy and Lemma, Citation2012). Indeed, some evidence suggests that nonpsychodynamic therapies may be effective in part because they utilize techniques (Gabbard, Citation1995; Kernberg, Citation2016; Stefana, Citation2017; Wallerstein, Citation1990) central to psychoanalytic theory and practice (Fonagy & Lemma, Citation2012).

The purpose of this study was to critically review the available studies on the effectiveness of psychoanalysis/long-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy for BD, provide a summary of the evidence base, and identify issues for future research in this area.

Method

The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) were searched to ensure that no similar reviews had previously been completed. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., Citation2018) statement was followed (see the Supplementary Online Material).

Eligibility criteria

The following eligibility criteria were applied: (1) published in a peer-reviewed journal; (2) inclusion of participants aged 18 years and older; (3) primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder; (4) administration of individual psychoanalysis or psychoanalytic psychotherapy; (5a: quantitative studies) improvement of depressive and manic symptoms, illness recurrence, or global functioning as a primary outcome; and (5b: single case reports) information about the improvement of mood symptoms, illness recurrence, or global functioning.

Information sources

The databases MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Psychoanalytic Electronic Publishing (PEP-Web), Scopus, and Web of Science were searched by title and abstract. The search in PEP-Web used full-text searching because this electronic archive did not allow abstract searching and was limited to those journals not indexed in one of the other databases. Studies were also found through searching the reference lists of the full articles screened and reviews of psychotherapy for BDs. The literature search was limited to English-language journal articles published from January 1990 to September 2021.

Search strategy

The words “psychoanalysis” and “psychoanalytic” were matched with “bipolar” and “manic depress*”.

Study selection

Two raters (A.S. and D.D.) independently and sequentially reviewed and screened titles and abstracts, and then full-text articles, for evidence that the studies met the eligibility criteria. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus reached through discussion.

Data collection process

A data extraction sheet for single-case reports was created and pilot-tested on five randomly selected included studies. One rater extracted the data while another checked it. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction

The following information was extracted from each single-case study: study characteristics – authors, year of publication, country; patient characteristics – age, sex, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5) diagnosis (derived from the patient’s clinical history and symptoms as described in the respective article, when the therapist used the term “manic depression”); and treatment characteristics – psychotherapy setting, status, weekly session frequency, duration, and presence/absence of pharmacotherapy.

Quality assessment

Given the characteristics of psychoanalytic single-case reports (Cena, Lazzaroni, & Stefana, Citation2021; Iwakabe & Gazzola, Citation2009) and the broader controversy regarding the critical appraisal of qualitative research (Dixon-Woods, Citation2004), no exclusion criteria based on the quality assessment of single case studies were applied.

Data analysis

The selected clinical case studies were inspected for patients, therapists, and treatment characteristics. The qualitative meta-analysis focused on identifying treatment outcomes regarding the patient’s mood symptoms, suicidality, hospitalizations, illness recurrence, or global functioning. In parallel, another analysis determined the elements and dynamics of the therapeutic relationship explicitly mentioned in the text. After these analyses were completed, two independent coders (licensed clinicians with both PsyD and PhD) checked the findings by comparing the analyses with the original clinical case reports. Finally, an attempt to contact all the corresponding authors of the included studies was made to check the accuracy of the data analysis results. Seven authors replied to our request.

Results

The initial search retrieved 209 items, with a further examination of seven articles captured via the reverse-search strategies detailed above (). Of these, 21 articles met the full inclusion criteria; all used a single case design. A summary of the characteristics and findings of each included study is presented in Supplemental Online Table S1.

Sample characteristics

A total of 26 single case reports involving adult patients affected by BD and treated with psychoanalysis (from now on called “therapy”) were found. Most patients were female (69%), were aged between 20 and 50 years old at the start of the therapy (31% each decade age range), and met the criteria for a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder (46%). Most of the patients (92%) received psychopharmacological medication during therapy, leaving one patient who did not receive any medication and another whose medication status was unknown. See for the characteristics of the patients.

Table 1. Characteristics of bipolar disorder patients and their psychotherapies

Treatment characteristics

Twelve therapies (46%) were still ongoing at the time of writing the article (mean duration 5.6 years; range 2–15 years; data based on 9 out of 12 clinical cases), and 14 (54%) had been terminated (mean duration 4.7 years; range 0.5–11 years; data based on 12 out of 14 clinical cases). The number of sessions per week ranged from one to six. The interventions offered ranged from the more traditional approach (see, for instance, Jackson, Citation1993; Kalita, Citation2021) to cases where the clinician did not use the free association method to analyze the patient’s conflict (Vanheule, Citation2017), asked the patient to fill in a daily mood chart (e.g., Salzman, Citation1998), or adopted a more active role in mobilizing family/environmental supports (Deitz, Citation1995; Salzman, Citation1998). See for the treatment characteristics.

Treatment outcomes

The findings indicate that 11 of 26 (42%) therapies reduced the patients’ depressive and/or (hypo)manic symptoms, and 7 of 11 therapies produced a reported improvement in psychosocial and/or work functioning. Additionally, seven therapies resulted in some improvement in functioning, but no information specifically about mood symptoms was reported. It should be noted that only 2 out of the 14 interrupted/completed therapies did not report any of the improvements mentioned above.

Of 13 patients who had a pretherapy history of psychiatric hospitalization, six had no further hospital admissions once the therapy started, six had a reduced the number or length of admissions, one experienced no significant change, and the remaining individual had an unclear record of hospitalizations. Overall, these numbers indicate that about three-quarters (77%) of patients with BD that underwent therapy achieved a lowered rate of hospitalization.

Five studies (19%) reported an improvement in medication adherence, while four declared that, due to therapy, patients required reduced medication doses (12%) or discontinued medication with the clinician’s knowledge (4%).

Suicidal thoughts and attempts were reported in seven case reports, four of which claimed that therapy helped patients to reduce, control, or remove suicidal states. Four studies indicated a reduction in level of patients’ self-destructive behaviors and attitudes (including drinking, risky sexual behaviors, and impulsivity).

Finally, a greater acceptance of bipolar illness by patients was described in three cases.

Regarding the combined treatment of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, about a third of the authors (35%) underline the fundamental role of medication in treating BD. Few of those explicitly stated that psychoanalysis (and, more generally, every talking cure) was less valuable than drugs. Some noted that psychotherapy alone was not sufficient to address the structural and functional deficits of these patients, especially during the period when they were manic or profoundly depressed.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that systematically reviews the effectiveness of psychoanalysis and long-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy in the treatment of individuals with BD. Although these pilot findings suggest that psychoanalysis may positively impact symptoms and global functioning in patients with BD, the underlying evidence is poor and should be confirmed by experimental studies.

This might seem somewhat not surprising, since one of the leading criticisms of psychoanalysis is that its treatment lacks empirical evidence. However, it should be noted that although there is relatively limited empirical evidence on psychoanalysis for complex mental disorders (Amir & Shefler, Citation2020; Beutel et al., Citation2004; de Maat et al., Citation2013; Fonagy et al., Citation2015; Huber, Zimmermann, Henrich, & Klug, Citation2012; Huber, Henrich, Clarkin, & Klug, Citation2013; Knekt et al., Citation2011; Leuzinger-Bohleber et al., Citation2019; Smit, Huibers, Ioannidis, van Dyck, van Tilburg, & Arntz, Citation2012), more several robust research studies have been carried out on psychoanalytically derived therapies. The latter fall under the broad umbrella of “psychodynamic psychotherapies” (Caro, Turner, & Macdonald, Citation2019; Kealy & Ogrodniczuk, Citation2019) and are usually less intensive and time limited, have a clearly defined theoretical basis, and are manualized (e.g., transference-focused therapy and dynamic interpersonal therapy).

In recent decades, numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses evaluating the efficacy of short- and long-term psychodynamic therapy have found effect sizes as large as those of the other main types of psychotherapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy (Abbass Hancock, Henderson, & Kisely, Citation2006; Keefe et al., Citation2020; Leichsenring, Citation2008; Leichsenring & Klein, Citation2014; Leichsenring & Rabung, Citation2011; Leichsenring, Rabung, & Leibing, Citation2004; Leichsenring et al., Citation2015; Steinert et al., Citation2017; Zhang et al., Citation2022). In addition, keeping the focus narrowed to mood disorders, a recent meta-analytic review indicates that psychodynamic therapies can be effective and acceptable in the treatment of adult depression, with no significant differences from other evidence-based therapies (Cuijpers et al., Citation2021). Similarly, the preliminary results of a review on the efficacy of intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy suggest a positive effect of this approach on depressive symptoms for patients with major depressive disorder (Cuijpers et al., Citation2021; Fonagy, Citation2015) or BD (Caldiroli et al., Citation2020). Another meta-analysis supports the effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy in reducing suicide attempts and self-harm in patients with heterogeneous diagnoses (Briggs et al., Citation2019), while a naturalistic longitudinal study indicates a significant decrease in the use of healthcare services, as well as a lasting reduction in absenteeism at work and days of psychiatric hospitalization over three years after therapy.

Overall, the above-mentioned research findings show that, contrary to widespread belief, the efficacy of psychodynamic approaches is empirically demonstrated. On the other hand, psychoanalysis is thus far supported by less strong evidence, especially for what concerns the treatment of individuals with BD, as revealed by this review.

Historically, there have been various obstacles to the implementation of empirical (methodologically rigorous) investigations of psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy, as well as to the participation of patients with BD in both therapy and research studies. These obstacles include, but are not limited to, the following four.

The first obstacle is the deep skepticism about the utility of empirical research – considered an “unwanted third” in treatment (de Maat et al., Citation2013) – that has characterized many members of the psychoanalytic community (Ortu, Citation2007; Yakeley, Hale, Johnston, Kirtchuk, & Shoenberg, Citation2014), as well as the resistance to the manualization of specific therapeutic approaches (Yakeley et al., Citation2014). Such skepticism seems to be fueled by the fact that psychoanalytic training is typically provided by private institutes instead of universities, where most of the trainers are clinicians affiliated to private associations and unfamiliar with scientific research methodologies and findings (Dimitrijević, Citation2018; Gonzalez-Torres, Fernandez-Rivas, & Penas, Citation2016). As a result, psychoanalysts usually have little or no knowledge about the epistemological and methodological aspects of empirical psychoanalytic research and its available findings (Stefana et al., Citation2022).

Second, the difficulties and limitations of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in the investigation of intensive and long-term treatments such as psychoanalysis (Leichsenring, Citation2005), including limited feasibility (de Jonghe et al., Citation2012), have led to a situation where most psychoanalytic studies are pre–post cohort studies lacking (randomized) control groups (de Maat et al., Citation2013). Moreover, many existing psychoanalytic studies are characterized by poor research methodology (Yakeley, Citation2018; Yakeley et al., Citation2014), which includes but is not limited to unclear definition of the treatment method and/or patient sample characteristics, inadequate sample sizes, poor monitoring of adherence to the treatment model, lack of blinding, and a lack of rigorous monitoring of interrater reliability.

Third, the availability of psychoanalytic psychotherapy as a treatment offered within the public health systems (where patients with BD are usually treated) of most developed countries is nowadays significantly lower than the availability of other forms of psychotherapy with a more substantial evidence base (Abbass et al., Citation2020; Kadish & Smith, Citation2020; Migone, Citation2020; Parth, Fischer-Kern, Rössler-Schülein, & Doering, Citation2020; Plakun, Citation2020; Yakeley, Citation2020). In addition, when offered within the public healthcare sector, psychoanalytic psychotherapy is usually time limited and conducted by trainees. At the same time, psychiatrists usually do not consider psychoanalysis as an evidence-based treatment (Paris, Citation2017; Salkovskis & Wolpert, Citation2012) or, consequently, as a therapeutic approach suitable for severe mental illnesses like BD. Consequently, recruitment for clinical studies is difficult, as psychoanalytic treatments for these people are fewer and sparse in private practice settings.

The final obstacle, following on from the previous points, is that it is hard to obtain research funding from the main funding agencies because the latter tend to give grants for psychological treatments with greater empirical validity. This fuels a vicious circle, with analytic researchers struggling to demonstrate this validity without being funded to perform such empirical studies (Buchholz & Kächele, Citation2018; McWilliams, Citation2013).

It has already been pointed out that the future of psychoanalysis in times of evidence-based practice could depend on proving the treatment outcomes for different patient groups (Leuzinger-Bohleber, Solms, & Arnold, Citation2021).

Research efforts should be directed to precisely defining conceptual and technical similarities and differences among different paradigms of psychotherapy and identifying which ones are most appropriate for patients with (a specific type of) BD within a complex context of treatment effectiveness and efficacy, cost-effectiveness, patient preference, and availability of psychological treatments (Yakeley, Citation2018).

A first step would be to develop manualized psychoanalytic approaches to BD, which consider the clinical and psychodynamic characteristics that accompany the different (i.e., manic or hypomanic, depressed, and euthymic) phases of bipolar illness. This approach could be quickly and easily adopted because psychoanalysis is traditionally less focused on symptoms of specific mental disorders and more inclined to observe and analyze intrapsychic and interpersonal problems and promote a diagnostic approach that is inferential, contextual, dimensional, and appreciative of the patient’s subjective experience (Lingiardi & McWilliams, Citation2017; McWilliams, Citation2011; Stefana & Gamba, Citation2013) to identify the underlying mental processes. Hence, apart from the traditional treatment outcomes used in RCTs, such as symptom reduction (McIntyre et al., Citation2020), mood instability (Kessing & Faurholt-Jepsen, Citation2022), or relapse prevention (Nestsiarovich, Gaudiot, Baldessarini, Vieta, Zhu, & Tohen., Citation2022), researchers willing to prove the efficacy of psychoanalytic interventions for serious conditions such as BD might want to power their studies for alternative relevant endpoints such as insight (Dell’Osso et al., Citation2002), cognitive reserve (Amoretti & Ramos-Quiroga, Citation2021), emotional and social cognition (Miskowiak and Varo, Citation2021; Varo et al., Citation2021), quality of life (Bonnín et al., Citation2019), or functioning (Vieta & Torrent, Citation2016).

Single-case studies – which historically have been quintessential for psychoanalytic research, theorization, and teaching (Desmet et al., Citation2013; Hinshelwood, Citation2013; Tuckett, Citation2008) – can play an important role in the study of BD only if the psychoanalytic narrative case study method will give way to quantitative single-case research methods (Kächele, Albani, & Pokorny, Citation2015) based on audio (or video) recordings of the whole treatment and supplemented by verbatim transcriptions and, possibly, computer-assisted and artificial intelligence content analysis.

After single-case, pre–post analysis is the most common study design in psychoanalytic research. However, psychoanalytic pre–post studies often do not meet all the methodological quality requirements (de Jonghe et al., Citation2012); thus future studies need to be improved by adhering to sound methodological principles (Barber, Citation2009) and using reporting guidelines such as the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statements (von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche, & Vandenbroucke, Citation2007) and the CONsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT; Schulz, Altman, Moher D, for the CONSORT Group, Citation2010).

Cohort studies can provide some evidential value in line with the extent to which their samples are large enough and the control group is comparable to the treatment group at the start, as well as about important aspects such as having or not having asked for psychological treatment, or having asked for a specific type of treatment instead of others. RCTs, which have the strongest scientific evidence within the evidence hierarchy of evidence-based medicine, should be the main objective of future research work in the psychoanalytic field. They can have strong evidential value within the limits of acceptable differences in setting (especially with respect to session frequency).

Finally, it will be important for future research to explore elements of the therapeutic relationship, such as the therapeutic alliance and countertransference (which originated in the psychoanalytic literature; Gelso, Citation2014; Stefana, Citation2015) for their influence on primary outcomes.

Limitations

The findings of the present review should be considered in light of several limitations. First, our review was entirely based on single case reports, so therefore the underlying evidence-based is overall poor. This was despite the fact that the search criteria would have captured quantitative papers or clinical trials, and it suggests a significant gap in the literature. However, systematically aggregating and synthesizing clinical case studies has clinical and research value when it enables the coverage of critical areas overlooked in large-scale RCTs (Iwakabe & Gazzola, Citation2009) – systematic reviews of case studies can help combat logical errors and biases in recall that otherwise characterize clinician recall and implementation (Caspar, Citation2007). This is notably the case given that no clinical trials have been conducted to establish the effectiveness of psychoanalysis for BD, as shown by our systematic literature search.

Second, the data reported in the studies differed in terms of levels of abstraction and quality of information on the outcome of the symptomatology. This could be partly because many (likely most) psychoanalytic therapists consider symptoms resulting from personality and intrapsychic problems. The latter are assumed to be the real core problem (Hill, Chui, & Baumann, Citation2013). They believe that symptoms improve once personality and intrapsychic changes have been obtained, but they fail to use those concepts as potential alternative endpoints for their studies.

Third, the focus on English-language studies could have excluded relevant studies published in other languages. However, 65% of the journals indexed in the PEP-Web archive, formed by the American Psychoanalytic Association and the Institute of Psychoanalysis and holding all the major psychoanalytic journals, are in English. Furthermore, 10 of 13 journals indexed in the category “Psychology, Psychoanalysis” (Social Sciences Citation Index [SSCI]) of Clarivate’s Journal Citation Reports publish articles only in English, while two of the remaining are multilingual (with English as one of the languages).

Fourth and last, patients with different subtypes of BD are included, and most diagnoses were not based on semi- or fully structured interviews. However, in this regard, bear in mind that although solid evidence indicates that a clinician who uses unstructured interviews tends to formulate and then assign a psychiatric diagnosis based on the presenting problem (usually within the first few minutes of the first encounter; Croskerry, Citation2003), even though these do not meet the formal criteria for a diagnosis (Miller, Citation2002), the therapists who treated the patients included in this review and wrote the case analyses had the benefit of considering tens or hundreds of weekly clinical interviews in formulating the diagnosis.

Conclusion

These pilot findings provide no robust evidence for psychoanalysis/psychoanalytic psychotherapy as an effective treatment for people with BD. Our findings are, however, exclusively based on a small number of psychoanalytic narrative case studies, which, from the perspective of evidence-based medicine, are of poor scientific strength. Therefore, we cannot draw conclusions about the effectiveness of psychoanalysis for BD. Experimental studies, especially randomized clinical trials, are urgently needed that do the following: (1) rely on a manualized psychoanalytic approach to BD; (2) describe patient samples in both psychoanalytic and International Classification of Diseases (ICD)/DSM diagnostic terms; (3) monitor the adherence of therapists to the manualized approach; (4) describe elements of the therapeutic relationship in detail; (5) apply validated process and outcome measures (including constructs such as acceptance, insight, cognitive reserve, emotional cognition, functioning, and quality of life, as well as traditional measures of symptom reduction that are often used as primary outcome measures); (6) include cost-effectiveness measures; (7) monitor mood swings; (8) monitor dropout; and (9) use long-term follow-up.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. All co-authors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript and there is no financial interest to report.

Author contribution statement

A.S. contributed to study design and drafted the study report. All authors reviewed the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the submitted version.

Supplemental online Table S1

Download Zip (33.6 KB)PRISMA-ScR Checklist

Download Zip (75.6 KB)Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here https://doi.org/10.1080/0803706X.2022.2097307

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alberto Stefana

Alberto Stefana PsyD, PhD, is a clinical psychologist, psychotherapist, and researcher. His main clinical area of interest is the psychotherapy of adults with psychological or psychiatric conditions or illness. He has worked as a psychotherapist at the psychiatric unit of the Spedali Civili Hospital of Brescia, still works in private practice, and is currently the recipient of a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Global Fellowship on the project “Evidence-based assessment in psychotherapy.” The main areas of scientific interest focus on the history and epistemology of psychoanalysis, evidence-based assessment and treatment, therapeutic relationship, and psychopathology. He has published more than 70 articles in international journals such as the International Journal of Psychoanalysis, Journal of Affective Disorders, and Bipolar Disorders, and the monograph History of counter transference: from Freud to the British Object Relations School (Routledge, 2017).

Daniela D’Imperio

Daniela D’Imperio PhD, PsyD, is a clinical psychologist, specialized in neuropsychology and psychotherapy. In her clinical and research activities, she mainly focuses on neuropsychological manifestations of adult neurological patients. Her interest ranges over all psychological aspects of the patients for a complete clinical view.

Antonios Dakanalis

Antonios Dakanalis MD, PsyD, PhD is a medical doctor specialised in mental health disorders research and psychotherapy practice. He currently works as a senior researcher at the psychiatric unit, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Milano Biccoca, where he also runs several funded cutting-edge and translational mental health research projects. He has published more than 150 scientific publications in the field of mental disorders, evidence-based practice and e-mental health services.

Eduard Vieta

Eduard Vieta MD, PhD, is Professor of Psychiatry and Chair at the University of Barcelona and Head of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology at the Hospital Clinic, where he also leads the Bipolar and Depressive Disorders Program in Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. His unit is one of the worldwide leaders in clinical care, teaching and research on affective disorders. Dr. Vieta is also the current Scientific Director of the Spanish Research Network on Mental Health (CIBERSAM). He has received the Aristotle award (2005), the Mogens Schou award (2007), the Strategic Research award of the Spanish Society of Biological Psychiatry (2009), the Official College of Physicians award to Professional Excellence (2011), the Colvin Price on Outstanding Achievement in Mood Disorders Research by the Brain and Be.

Paolo Fusar-Poli

Paolo Fusar-Poli MD, PhD, is a Professor of Preventive Psychiatry at the Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience (IoPPN), King's College London (KCL), where he heads the Early Psychosis: Intervention and Clinical-detection Laboratory (EPIC Lab). He is also a consultant psychiatrist in the Outreach And Support In South-London (OASIS) mental health service at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. He is also associate professor at the University of Pavia, Italy. Much of his research utilises evidence-based medicine, clinical prediction, neuroscience and experimental therapeutics and aims to develop new and effective strategies to improve the prevention of mental disorders.

Eric Youngstrom

Eric Youngstrom Ph.D., is a professor of Psychology and Neuroscience, and Psychiatry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and an adjunct professor of Psychology at the Korea University in Seoul, South Korea. He is also the Acting Director of the Center for Excellence in Research and Treatment of Bipolar Disorder. He is a two-time Past President of the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology and served as president of Division 5 of the American Psychological Association (Qualitative & Quantitative Methods). His research improves clinical assessment instruments for making better differential diagnoses, predictions about future functioning, and monitoring of treatment progress, especially for bipolar disorder. Since 2018, in an effort for open science, he has served as an editor on the Wiki Journal of Medicine Editorial Board. Most notably, Dr. Youngstrom is the proud Co-Founder, and Executive Director of Helping Give Away Psychological Science (HGAPS) (https://www.hgaps.org/). This 501c3 nonprofit service-based education organization brings the best psychological information to the most who will benefit from it.

References

- Abbass, A.A., Hancock, J.T., Henderson, J., & Kisely, S.R. (2006). Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapies for common mental disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (4), CD004687.

- Abbass, A.A., Tasca, G.A., Vasiliadis, H.-M., Spagnolo, J., Kealy, D., Hewitt, P.L., et al. (2020). Psychodynamic therapy in Canada in the era of evidence-based practice. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 34, 78–99.

- Abbass, A., Town, J., Johansson, R., Lahti, M., & Kisely, S. (2019). Sustained reduction in health care service usage after adjunctive treatment of intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy in patients with bipolar disorder. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 47, 99–112.

- Amir, I., & Shefler, G. (2020). The “Lechol Nefesh” project: Intensive and long term psychoanalytic psychotherapy in public mental health centers. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 40, 536–549.

- Amoretti, S., & Ramos-Quiroga, J.A. (2021). Cognitive reserve in mental disorders. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 49, 113–115.

- Barber, J.P. (2009). Toward a working through of some core conflicts in psychotherapy research. Psychotherapy Research, 19, 1–12.

- Beutel, M.E., Rasting, M., Stuhr, U., Rüger, B., & Leuzinger-Bohleber, M. (2004). Assessing the impact of psychoanalyses and long-term psychoanalytic therapies on health care utilization and costs. Psychotherapy Research, 14, 146–160.

- Bonnín, C. del M., Reinares, M., Martínez-Arán, A., Jiménez, E., Sánchez-Moreno, J., Solé, B, et al. (2019). Improving functioning, quality of life, and well-being in patients with bipolar disorder. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 22, 467–477.

- Briggs, S., Netuveli, G., Gould, N., Gkaravella, A., Gluckman, N.S., Kangogyere, P., et al. (2019). The effectiveness of psychoanalytic/psychodynamic psychotherapy for reducing suicide attempts and self-harm: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 214, 320–328.

- Buchholz, M.B., & Kächele, H. (2018). Teaching research methods to psychoanalysts: Experiences from PSAID. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 27, 114–120.

- Burgos-Julián, F.A., Ruiz-Íñiguez, R., Peña-Ibáñez, F., Montero, A.C., & Santed-Germán, M.A. (2022). Mindfulness-based and mindfulness-informed interventions in bipolar disorder: A meta-analysis based on Becker’s method. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 2022 Jan 31. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2717. Online ahead of print.

- Caldiroli, A., Capuzzi, E., Riva, I., Russo, S., Clerici, M., Roustayan, C., et al. (2020). Efficacy of intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy in mood disorders: A critical review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 273, 375–379.

- Caro, P., Turner, W., & Macdonald, G. (2019). Comparative effectiveness of interventions for treating the psychological consequences of sexual abuse in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (6), CD013361.

- Carvalho, A.F., Firth, J., & Vieta, E. (2020). Bipolar disorder. New England Journal of Medicine, 383, 58–66.

- Caspar, F. (2007). Two babies in two bathtubs – don’t throw out either, but rather advance both: Discussion of Edwards, Eells, and Messer papers. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy, 3, 59–67.

- Cassidy, J., & Shaver, P.R. (2018). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- Cena, L., Lazzaroni, S., & Stefana, A. (2021). The psychological effects of stillbirth on parents: A qualitative evidence synthesis of psychoanalytic literature. Zeitschrift für Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie, 67, 329–350.

- Chatterton, M.L., Stockings, E., Berk, M., Barendregt, J.J., Carter, R., & Mihalopoulos, C. (2017). Psychosocial therapies for the adjunctive treatment of bipolar disorder in adults: Network meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 210, 333–341.

- Chiang, K.-J., Tsai, J.-C., Liu, D., Lin, C.-H., Chiu, H.-L., & Chou, K.-R. (2017). Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy in patients with bipolar disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE, 12, e0176849.

- Cipriani, A., Barbui, C., Salanti, G., Rendell, J., Brown, R., & Stockton, S., et al. (2011). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: A multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet, 378, 1306–1315.

- Cipriani, A., Furukawa, T.A., Salanti, G., Geddes, J.R., Higgins, J.P., Churchill, R., et al. (2009). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: A multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet, 373, 746–758.

- Cipriani, A., Zhou, X., Giovane, C.D., Hetrick, S.E., Qin, B., Whittington, C., et al. (2016). Comparative efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: A network meta-analysis. Lancet, 388, 881–890.

- Colom, F., Vieta, E., Martínez-Arán, A., Reinares, M., Goikolea, J.M., Benabarre, A., et al. (2003). A randomized trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 402.

- Correll, C.U., Sheridan, E.M., & DelBello, M.P. (2010). Antipsychotic and mood stabilizer efficacy and tolerability in pediatric and adult patients with bipolar I mania: A comparative analysis of acute, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disorders, 12, 116–141.

- Croskerry, P. (2003). The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Academic Medicine, 78, 775–80.

- Cuijpers, P., Quero, S., Noma, H., Ciharova, M., Miguel, C., Karyotaki, E., et al. (2021). Psychotherapies for depression: a network meta-analysis covering efficacy, acceptability and long-term outcomes of all main treatment types. World Psychiatry, 20, 283–293.

- De Hert, M., Correll, C.U., Bobes, J., Cetkovich-Bakmas, M., Cohen, D., Asai, I., et al. (2011). Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry, 10, 52–77.

- Deitz, I. J. (1995). The self-psychological approach to the bipolar spectrum disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 23, 475–92.

- de Jonghe, F., de Maat, S., Barber, J.P., Abbas, A., Luyten, P., Gomperts, W., et al. (2012). Designs for studying the effectiveness of long-term psychoanalytic treatments: Balancing level of evidence and acceptability to patients. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 60, 361–387.

- de Maat, S., de Jonghe, F., de Kraker, R., Leichsenring, F., Abbass, A., Luyten, P., et al. (2013). The current state of the empirical evidence for psychoanalysis: A meta-analytic approach. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 21, 107–137.

- Dell’Osso, L., Pini, S., Cassano, G.B., Mastrocinque, C., Seckinger, R.A., Saettoni, M., et al. (2002). Insight into illness in patients with mania, mixed mania, bipolar depression and major depression with psychotic features: Insight into illness in patients with mania. Bipolar Disorders, 4, 315–322.

- Desmet, M., Meganck, R., Seybert, C., Willemsen, J., Geerardyn, F., Declercq, F., et al. (2013). Psychoanalytic single cases published in ISI-ranked journals: The construction of an online archive. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82, 120–121.

- Dimitrijević, A. (2018). A mixed-model for psychoanalytic education. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 27, 121–125.

- Dixon-Woods, M. (2004). The problem of appraising qualitative research. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 13, 223–225.

- Fonagy, P. (2015). The effectiveness of psychodynamic psychotherapies: An update. World Psychiatry, 14, 137–150.

- Fonagy, P., & Lemma, A. (2012). Does psychoanalysis have a valuable place in modern mental health services? Yes. BMJ, 344, e1211–e1211.

- Fonagy, P., Rost, F., Carlyle, J., McPherson, S., Thomas, R., Pasco Fearon, R.M., et al. (2015). Pragmatic randomized controlled trial of long-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy for treatment-resistant depression: The Tavistock Adult Depression Study (TADS). World Psychiatry, 14, 312–321.

- Frank, E. (2007). Treating bipolar disorder: A clinician’s guide to interpersonal and social rhythm therapy. New York: Guilford Press.

- Frank, E., Benabou, M., Bentzley, B., Bianchi, M., Goldstein, T., Konopka, G., et al. (2014). Influencing circadian and sleep-wake regulation for prevention and intervention in mood and anxiety disorders: What makes a good homeostat? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1334, 1–25.

- Freud, S. (1989). The ego and the id (1923). TACD Journal, 17, 5–22.

- Gabbard, G.O. (1995). Countertransference: The emerging common ground. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 76(Pt 3), 475–485.

- Gabbard, G.O. (2017). Long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy: A basic text (3rd ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

- Geddes, J.R., & Miklowitz, D.J. (2013). Treatment of bipolar disorder. Lancet, 381, 1672–1682.

- Gelso, C. (2014). A tripartite model of the therapeutic relationship: Theory, research, and practice. Psychotherapy Research, 24, 117–131.

- Gonzalez-Torres, M.A., Fernandez-Rivas, A., & Penas, A. (2016). In the mind of the teacher: Psychoanalytic papers as key elements in a scientific endeavour. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 25, 123–129.

- Goodwin, G., Haddad, P., Ferrier, I., Aronson, J., Barnes, T., Cipriani, A. et al. (2016). Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: Revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 30, 495–553.

- Grande, I., Berk, M., Birmaher, B., & Vieta, E. (2016). Bipolar disorder. Lancet, 387, 1561–1572.

- Harari, E., & Grant, D.C. (2022). Clinical wisdom, science and evidence: The neglected gifts of psychodynamic thinking. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 56, 594–602.

- Hill, C.E., Chui, H., & Baumann, E. (2013). Revisiting and reenvisioning the outcome problem in psychotherapy: An argument to include individualized and qualitative measurement. Psychotherapy, 50, 68–76.

- Hinshelwood, R.D. (2013). Research on the couch: Single-case studies, subjectivity, and psychoanalytic knowledge. Hove/New York: Routledge.

- Huber, D., Henrich, G., Clarkin, J., & Klug, G. (2013). Psychoanalytic versus psychodynamic therapy for depression: A three-year follow-up study. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 76, 132–149.

- Huber, D., Zimmermann, J., Henrich, G., & Klug, G. (2012). Comparison of cognitive-behaviour therapy with psychoanalytic and psychodynamic therapy for depressed patients – A three-year follow-up study. Zeitschrift für Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie, 58, 299–316.

- Iwakabe, S., & Gazzola, N. (2009). From single-case studies to practice-based knowledge: Aggregating and synthesizing case studies. Psychotherapy Research, 19, 601–611.

- Jackson, M. (1993). Manic-depressive psychosis: Psychopathology and individual psychotherapy within a psychodynamic milieu. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 7, 103–33.

- Janis, R.A., Burlingame, G.M., Svien, H., Jensen, J., & Lundgreen, R. (2021). Group therapy for mood disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy Research, 31, 342–358.

- Kächele, H., Albani, C., & Pokorny, D. (2015). From a psychoanalytic narrative case study to quantitative single-case research. In O.C.G. Gelo, A. Pritz, and B. Rieken (eds.), Psychotherapy Research (pp. 367–379). Vienna: Springer Vienna.

- Kadish, Y., & Smith, C. (2020). Psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy in the South African context. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 34, 163–179.

- Kalin, N.H. (2020). Advances in understanding and treating mood disorders. American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 177, 647–650.

- Kalita, L. (2021). Is psychodynamic psychotherapy a useful approach in treatment of bipolar disorder? A review of research, actualization of technique and clinical illustrations. Psychiatria Polska, 55, 145–70.

- Kealy, D., & Ogrodniczuk, J.S. (2019). Theoretical evolution in psychodynamic psychotherapy. In D. Kealy, and J.S. Ogrodniczuk (eds.), Contemporary Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (pp. 3–17). London: Elsevier.

- Keefe, J.R., McMain, S.F., McCarthy, K.S., Zilcha-Mano, S., Dinger, U., Sahin, Z., et al. (2020). A meta-analysis of psychodynamic treatments for borderline and cluster C personality disorders. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 11, 157–169.

- Kernberg, O.F. (2016). The four basic components of psychoanalytic technique and derived psychoanalytic psychotherapies. World Psychiatry, 15, 287–288.

- Kessing, L.V., & Faurholt-Jepsen, M. (2022). Mood instability – A new outcome measure in randomised trials of bipolar disorder? European Neuropsychopharmacology, 58, 39–41.

- Knekt, P., Lindfors, O., Laaksonen, M.A., Renlund, C., Haaramo, P., Härkänen, T., et al. (2011). Quasi-experimental study on the effectiveness of psychoanalysis, long-term and short-term psychotherapy on psychiatric symptoms, work ability and functional capacity during a 5-year follow-up. Journal of Affective Disorders, 132, 37–47.

- Lam, C., & Chung, M.-H. (2021). A meta-analysis of the effect of interpersonal and social rhythm therapy on symptom and functioning improvement in patients with bipolar disorders. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 16, 153–165.

- Leichsenring, F. (2005). Are psychodynamic and psychoanalytic therapies effective? A review of empirical data. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 86, 841–868.

- Leichsenring, F. (2008). Effectiveness of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of the America Medical Association, 300, 1551.

- Leichsenring, F., & Klein, S. (2014). Evidence for psychodynamic psychotherapy in specific mental disorders: A systematic review. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 28, 4–32.

- Leichsenring, F., & Rabung, S. (2011). Long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy in complex mental disorders: Update of a meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199, 15–22.

- Leichsenring, F., Luyten, P., Hilsenroth, M.J., Abbass, A., Barber, J.P., Keefe, J.R., et al. (2015). Psychodynamic therapy meets evidence-based medicine: A systematic review using updated criteria. Lancet Psychiatry, 2, 648–660.

- Leichsenring, F., Rabung, S., & Leibing, E. (2004). The efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy in specific psychiatric disorders: A meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 1208.

- Leuzinger-Bohleber, M., Hautzinger, M., Fiedler, G., Keller, W., Bahrke, U., Kallenbach, L., et al. (2019). Outcome of psychoanalytic and cognitive-behavioural long-term therapy with chronically depressed patients: A controlled trial with preferential and randomized allocation. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 64, 47–58.

- Leuzinger-Bohleber, M., Solms, M., & Arnold, S. (2021). Outcome research and the future of psychoanalysis: Clinicians and researchers in dialogue. New York: Routledge.

- Lingiardi, V., & McWilliams, N. (2017). Psychodynamic diagnostic manual: PDM-2. New York: Guilford Press.

- Makari, G. (2008). Revolution in mind: The creation of psychoanalysis. Carlton, VIC: Melbourne University Publishing.

- Malhi, G.S., Bassett, D., Boyce, P., Bryant, R., Fitzgerald, P.B., Fritz, K., et al. (2015). Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49, 1087–1206.

- McIntyre, R.S., Berk, M., Brietzke, E., Goldstein, B.I., López-Jaramillo, C., Kessing, L.V., et al. (2020). Bipolar disorders. Lancet, 396, 1841–1856.

- McWilliams, N. (2011). Psychoanalytic diagnosis: Understanding personality structure in the clinical process. New York: Guilford Press.

- McWilliams, N. (2013). Psychoanalysis and research: Some reflections and opinions. Psychoanalytic Review, 100, 919–945.

- Migone, P. (2020). Psychodynamic therapy in the public sector in Italy: Then and now. The opportunity of evidence-based practice in the birthplace of ‘care-in-the-community.’ Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 34, 147–162.

- Miklowitz, D.J., Otto, M.W., Frank, E., Reilly-Harrington, N.A., Wisniewski, S.R., Kogan, J.N., et al. (2007). Psychosocial treatments for bipolar depression – A 1-year randomized trial from the systematic treatment enhancement program. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 419–427.

- Miklowitz, D.J., Otto, M.W., Wisniewski, S.R., Araga, M., Frank, E., Reilly-Harrington, N.A., et al.(2006). Psychotherapy, symptom outcomes, and role functioning over one year among patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 57, 959–965.

- Miller, P.R. (2002). Inpatient diagnostic assessments: 3. Causes and effects of diagnostic imprecision. Psychiatry Research, 111, 191–197.

- Miskowiak, K.W., & Varo, C. (2021). Social cognition in bipolar disorder: A proxy of psychosocial function and novel treatment target? European Neuropsychopharmacology, 46, 37–38.

- Moreira, A.L.R., Van Meter, A., Genzlinger, J., & Youngstrom, E.A. (2017). Review and meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies of adult bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78, e1259–e1269.

- Nestsiarovich, A., Gaudiot, C.E.S., Baldessarini, R.J., Vieta, E., Zhu, Y., & Tohen, M. (2022). Preventing new episodes of bipolar disorder in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 54, 75–89.

- Ortu, F. (2007). Psychoanalysis and empirical research. Rivista di Psicologia Clinica, 1, 31–40.

- Oud, M., Mayo-Wilson, E., Braidwood, R., Schulte, P., Jones, S.H., Morriss, R., et al. (2016). Psychological interventions for adults with bipolar disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 208, 213–222.

- Pacchiarotti, I., Bond, D.J., Baldessarini, R.J., Nolen, W.A., Grunze, H., Licht, R.W., et al. (2013). The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD). Task Force Report on Antidepressant Use in Bipolar Disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 1249–1262

- Paris, J. (2017). Is psychoanalysis still relevant to psychiatry? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 62, 308–312.

- Parth, K., Fischer-Kern, M., Rössler-Schülein, H., & Doering, S. (2020). Psychoanalytic psychotherapy in Austria. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 34, 111–128.

- Plakun, E.M. (2020). Access to psychoanalysis and psychotherapy in the US. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 34, 100–110.

- Plans, L., Barrot, C., Nieto, E., Rios, J., Schulze, T.G., Papiol, S., et al. (2019). Association between completed suicide and bipolar disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Affective Disorders, 242, 111–122.

- Salkovskis, P., & Wolpert, L. (2012). Does psychoanalysis have a valuable place in modern mental health services? No. BMJ, 344, e1188–e1188.

- Salzman, C. (1998). Integrating pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in the treatment of a bipolar patient. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 686–8.

- Schulz, K.F., Altman, D.G., Moher, D., for the CONSORT Group (2010). CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ, 340, c332–c332.

- Smit, Y., Huibers, M.J.H., Ioannidis, J.P.A., van Dyck, R., van Tilburg, W., & Arntz, A. (2012). The effectiveness of long-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy—A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 81–92.

- Stefana, A. (2015). The origins of the notion of countertransference. Psychoanalytic Review, 102, 437–460.

- Stefana, A. (2017). History of countertransference: From Freud to the British object relations school. London: Routledge.

- Stefana, A., & Gamba, A. (2013). Semeiotica e diagnosi psico(pato)logica [Psycho(patho)logical semeiotics and diagnosis]. Journal of Psychopathology, 19, 351–358.

- Stefana, A., Celentani, B., Dimitrijevic, A., Migone, P., & Albasi, C. (2022). Where is psychoanalysis today? Sixty-two psychoanalysts share their subjective perspectives on the state of the art of psychoanalysis: A qualitative thematic analysis. International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 1–13.

- Stefana, A., Paolo Fusar-Poli, P., D’Imperio, D., Choplin, E., Dakanalis, A., Vieta, E., & Youngstrom, E.A. (under review). Mapping the psychoanalytic literature on bipolar disorder: A scoping review of journal articles.

- Stefana, A., Youngstrom, EA., Chen, J., Hinshaw, S., Maxwell, V., Michalak, E., et al. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic is a crisis and opportunity for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 22, 641–643.

- Steinert, C., Munder, T., Rabung, S., Hoyer, J., & Leichsenring, F. (2017). Psychodynamic therapy: As efficacious as other empirically supported treatments? A meta-analysis testing equivalence of outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174, 943–953.

- Torrent, C., Bonnin, C. del M., Martínez-Arán, A., Valle, J., Amann, B.L., González-Pinto, A., et al. (2013). Efficacy of functional remediation in bipolar disorder: A multicenter randomized controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 852–859.

- Tricco, A.C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K.K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., et al. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, 467–473.

- Tuckett, D. (2008). Psychoanalysis comparable and incomparable. London: Routledge.

- Vanheule, S. (2017). Conceptualizing and treating psychosis: A Lacanian perspective. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 33, 388–98.

- Varo, C., Kjærstad, H.L., Poulsen, E., Meluken, I., Vieta, E., Kessing, L.V., et al. (2021). Emotional cognition subgroups in mood disorders: Associations with familial risk. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 51, 71–83.

- Vieta, E., & Torrent, C. (2016). Functional remediation: The pathway from remission to recovery in bipolar disorder: World Psychiatry, 15, 288–289.

- Vieta, E., Berk, M., Schulze, T.G., Carvalho, A.F., Suppes, T., Calabrese, J.R., et al. (2018). Bipolar disorders. Nat Reviews. Disease Primers, 4, 18008.

- von Elm, E., Altman, D.G., Egger, M., Pocock, S.J., Gøtzsche, P.C., & Vandenbroucke, J.P. (2007). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet, 370, 1453–1457.

- Vos, T., Barber, R.M., Bell, B., Bertozzi-Villa, A., Biryukov, S., Bolliger, I., et al. (2015). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet, 386, 743–800.

- Wallerstein, R.S. (1990). Psychoanalysis: The common ground. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 71(Pt 1), 3–20.

- Xuan, R., Li, X., Qiao, Y., Guo, Q., Liu, X., Deng, W., et al. (2020). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113116.

- Yakeley, J. (2018). Psychoanalysis in modern mental health practice. Lancet Psychiatry, 5, 443–450.

- Yakeley, J. (2020). Editorial. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 34, 73–77.

- Yakeley, J., Hale, R., Johnston, J., Kirtchuk, G., & Shoenberg, P. (2014). Psychiatry, subjectivity and emotion – deepening the medical model. Psychiatric Bulletin, 38, 97–101.

- Yatham, L.N., Kennedy, S.H., Parikh, S.V., Schaffer, A., Bond, D.J., Frey, B.N., et al. (2018). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 20, 97–170.

- Ye, B.-Y., Jiang, Z.-Y., Li, X., Cao, B., Cao, L.-P., Lin, Y., et al. (2016). Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy in treating bipolar disorder: An updated meta-analysis with randomized controlled trials: CBT for bipolar disorder. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 70, 351–361.

- Youngstrom, E.A., Birmaher, B., & Findling, R.L. (2008). Pediatric bipolar disorder: Validity, phenomenology, and recommendations for diagnosis. Bipolar Disorders, 10, 194–214.

- Youngstrom, E.A., Hinshaw, S.P., Stefana, A., Chen, J., Michael, K., Van Meter, A., et al. (2020a). Working with bipolar disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic: Both crisis and opportunity. WikiJournal of Medicine, 7, 4.

- Youngstrom, E.A., Morton, E.E., & Murray, G. (2020b). Bipolar spectrum disorders. In E. A. Youngstrom, M. J. Prinstein, E. J. Mash and R. A. Barkley (eds.), Assessment of disorders in childhood and adolescence (5th ed., pp. 192–244). New York: Guilford Press.

- Zhang, Q., Yi, P., Song, G., Xu, K., Wang, Y., Liu, J., et al. (2022). The efficacy of psychodynamic therapy for social anxiety disorder–A comprehensive meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 309, 114403.