ABSTRACT

The European Union’s regional policy, one of the world’s largest public policies, promotes project activities funded by the Structural Funds, including the European Social Fund (ESF). Besides the goals of increased employment, competitiveness and growth, the ESF aims to increase gender equality (GE). GE is implemented in the ESF through administrative processes in national and regional institutions. Despite public administration’s central role in defining and organizing the GE policy, administrative variations have received little attention. Drawing on interviews and policy documents, this study analyses differences in Sweden and Spain to explore the ideological consequences of governance structures for GE policies.

Introduction

The European Union’s (EU’s) regional policy is one of the world’s largest public policies in terms of budget size and geographical range. One of the EU’s main social instruments, it constitutes a comprehensive macroeconomic redistribution policy (Brine, Citation2002; Piattoni, Citation2010, p. 95; Tomé, Citation2013), aiming to reduce territorial, economic and social disparities within the EU. Representing about one-third of the EU’s total budget, the policy promotes project activities financed by the Structural Funds, including the European Social Fund (ESF). During the period under study, the ESF’s goals were to increase employment, competitiveness and growth, as well as gender equality (GE) (Commission, Citation2007a, Citation2007b, Citation2008). Public and private bodies, as well as non-profit actors, can apply for the ESF to run such projects, aimed at increasing the employability of both employed and unemployed individuals through skills development initiatives.

Despite the lack of studies on the ESF’s GE policy at the national level, research has shown that implementation of the Structural Funds and GE policies varies among the member states (EIGE, Citation2018, p. 27; Allwood, Citation2013; Stratigaki, Citation2004). The EU multi-level governance, within which ESF is implemented (López-Santana, Citation2006; Trubek & Trubek, Citation2005), contributes to making these variations possible by allowing the member states to choose how to organize and implement the ESF policy. At the same time, due to the EU’s limited legal authority over social issues, the European Commission (hereafter, Commission) depends on national administrations to enforce the policy. The ESF is managed through administrative processes in national and regional institutions. By organizing and defining priorities and control techniques, the ESF administration sets the framework for project funding, which is important for the ESF’s long-term impact on the labour market. While public administration plays a central role in defining and organizing the ESF’s GE policy, less is known about how these processes are played out in practice and what their significance is for defining a gender perspective in the member states.

This article, based on my doctoral dissertation (Carlsson, Citation2019), aims to investigate the national ESF administration’s role in the uneven attention to the ESF’s GE policy in member states. Comparing organizational forms and control techniques in national governance structures during the programming period 2007–2013 in Sweden and Spain enables the investigation of whether governance structures in different countries contributed to reinforcing or challenging the EU’s interpretation of GE as a matter of growth. The theoretical research question concerns the relation between public administration governance structures and the GE policies’ ideological content.

Previous feminist studies argue that “bureaucracy is a structural manifestation of male domination” (Ashcraft, Citation2001, p. 1302) and that there has “always been an uneasy relationship between feminism and bureaucracy” (Ferguson, Citation1984, p. 3; see also Acker, Citation1990; Stivers, Citation1993). In contrast, feminist studies on “post-bureaucratic” governance structures contend that these tend to depoliticize GE issues, thus limiting the possibilities for change (Hudson & Rönnblom, Citation2007). This study shows that different ways of organizing and controlling GE policy in public administration affect the conditions for ideological policy outcomes, i.e. administrative processes have ideological consequences for GE policy. In contrast to previous feminist studies on bureaucracy, this study argues that non-feminist forms of organization can be helpful to push for feminist ideas; a centralized hierarchical organizational form and the use of rule-driven and mandatory control techniques can be beneficial to GE policies and increase the discretion of feminist public administrators. At the same time, more flexible organizational forms with voluntary participation poses a risk for feminist perspectives to be neglected. The results point to the need for feminist scholars, interested in the terms and conditions for GE policy outcome, to engage with practices and structures of the public administration.

European social fund and gender equality

Throughout the EU’s history, tensions have existed between economic and social perspectives in formulating GE policy (Allwood, Citation2013; Elomäki, Citation2015; Stratigaki, Citation2004). However, scholars have argued that the EU approaches GE policy, including the ESF’s GE policy, from a neoliberal perspective, emphasizing economic growth as the ultimate goal (see Lewis & Giullari, Citation2005; Lombardo, Citation2008; Squires, Citation2007; Walby, Citation2004). Institutions and organizations have legitimized this market-oriented discourse as the economic case (Elomäki, Citation2015) or the business case (True, Citation2009) for GE. The emergence of a neoliberal GE discourse has been labelled as a change from state feminism to market feminism (Kantola & Squires, Citation2012). The neoliberal discourse is identifiable in the ESF, where social and growth perspectives are intertwined: “[t]he ESF shall support the priorities of the Community as regards the need to reinforce social cohesion, strengthen productivity and competitiveness, and promote economic growth and sustainable development” (Commission (EC) No. 1081/2006: 14).

The objectives and budget of the EU Structural Funds are formulated in programme periods (Hooghe, Citation1996). In 2007–2013, the ESF’s overall objectives were increased regional competitiveness and increased regional cohesion. In recent decades, gender mainstreaming has been the EU’s most important policy instrument in the GE field (Lombardo & Meier, Citation2006; Woodward, Citation2012). The ESF regulation basically allows the member states to determine their implementation strategy but promotes mainstreaming: “[a] gender mainstreaming approach should be combined with specific action to increase the sustainable participation and progress of women in employment” (Commission (EC) No. 1081/2006: 13). In addition to the overall objectives, eligibility for funding requires the applicant organizations to implement a gender perspective with the responsibility at the national level. The mainstreaming perspective aims to “improve access to employment, increase the sustainable participation and progress of women in employment and reduce gender-based segregation in the labour market” (Commission (EC) No. 1081/2006, Article 3). The regulation assumes that the gender perspective can be integrated into the ESF’s overall labour market and growth policy and reflects the assumption that a gender-integrated labour market generates increased human capital, in turn stimulating growth. The understandings implied in the ESF regulation are similar to those in related EU policies including the Lisbon Strategy (Rönnblom, Citation2009) and the European Employment Strategy (Smith & Villa, Citation2010).

ESF has generally contributed to an increase in the EU’s gender mainstreaming methods (Booth & Bennett, Citation2002). Even though studies on the implementation of the ESF’s GE policy in the member states are scarce, EIGE reports that the implementation of a gender perspective is more visible in national ESF operational programmes than in other structural and investment funds (EIGE, Citation2018). The GE perspective is often applied to the project analysis and planning phase but less to the implementation and monitoring phase. There is a lack of studies on the ESF GE policy outcome and the promotion of GE at national ESF level varies. However, Zartaloudis (Citation2015) argues that the ESF has contributed to a general promotion of GE policies in Greece (promotion of work/private life balance and financing of childcare) and Portugal (promotion of gender mainstreaming). Still, Ahrens and Callerstig (Citation2017) argues that Sweden’s ESF GE work was, compared to Germany, less advanced during the 2007–2013 period. This was due to the reputation of Sweden being prominent in GE policies, leading to a lack of control at European and national levels.

Studies have also observed that conformity between European and national ESF policy formulations vary. A comparative study shows that ESF objectives in Spain are interpreted based on the national context (Sanchez Salgado, Citation2013) rather than on the EU context to a greater extent than is the case in France. In contrast, studies in Germany, Poland (Büttner & Leopold, Citation2016) and Belgium (Verschraegen, Vanhercke, & Verpoorten, Citation2011) indicate a greater adjustment to the EU through the ESF at the national level. The adjustment is observed in implementation methods, including an increased number of project activities, as well as increased documentation, monitoring and evaluation. New markets for EU experts and services have emerged, as well as linguistic adaptations to EU terminology. The idea that the Structural Funds should be implemented in collaborative networks and partnerships has changed the prerequisites for the member states’ institutional conditions (Carlsson & Mukhtar-Landgren, Citation2018). However, the partnership principle has been implemented to a lesser extent in Spain (Bache, Citation2008, pp. 66–67).

Policy governance and ideological content

Since the 1980s, the public sector has undergone a shift from a bureaucratic government to network-oriented governance, with the EU described as an example (Marks, Citation1993; Rhodes, Citation1996). The EU constitutes a new form of governance, characterized by two factors. First, several institutional levels are involved in decision-making and implementation processes. Second, these different actors collaborate in networks. From a democratic perspective, the network model has been described as beneficial in terms of the actors’ broad participation. However, research has questioned whether the network-oriented model has offered a real difference to the bureaucracy’s perceived efficiency and equality problems or whether bureaucracy only takes other more camouflaged forms in the networks (Davies, Citation2011; Olsson, Citation2003).

Bureaucracy has also been subject to a feminist critique, with scholars arguing that a bureaucracy with distinct hierarchies impedes equal social relations and that bureaucratic norms and administrative approaches are depoliticizing and thus counterproductive for GE work (see Alnebratt & Rönnblom, Citation2016; Ashcraft, Citation2001; Ferguson, Citation1984; Pringle, Citation1989; Stivers, Citation1993). A common perception is that bureaucracies oppose change and prevent the impact of political content (see Graeber, Citation2015; Weber, Citation1978). The bureaucracy’s emphasis on hierarchies, formal rationality, expertise and confidentiality represses progressiveness and social relations. As a power structure, the bureaucracy is assumed to counteract democracy, both practically and fundamentally. Accordingly, the hierarchy recreates unequal social relationships at both organizational and societal levels (Diefenbach & Todnem By, Citation2012). Feminist studies have also shown that post-bureaucratic structures, such as networks, contribute to the depoliticization of equality policies because networks are based on consensus that tends to limit the possibility of conflicts and differences of opinion (Hudson & Rönnblom, Citation2007; Isaksson, Citation2010). Network management is criticized for resulting in an increased focus on growth, partly because of private actors’ involvement in the new public governance, which tends to compromise social values (Prügl & True, Citation2014).

However, there is a lack of empirical studies comparing the impact of different governance structures on GE policy. To understand the political content permeating the administrative processes within the governance structure, the concept of ideology is used in this study. In this context, ideology is derived from a broad definition entailing interconnected beliefs and assumptions about the world that have implications for society’s power relations (Eagleton, Citation2007, p. 5). The ideology does not primarily consist of distinct explanations of the programme but of a specific set of implicit or explicit assumptions, expressed and maintained through action. Ideology thus operates through social processes that tend to recreate specific interpretations of reality and eliminate or dismiss others. These processes make social circumstances appear naturalized (Eagleton, Citation2007; Hawkes, Citation2003; Rehmann, Citation2013). Ideological assumptions are formulated in relation to an ideational, institutional and material context; ideological processes are formed, reproduced and changed in relation to societal power relations. They constitute a condition for the ways in which political goals and decisions are implemented, and they cooperate with governance structures. In turn, these governance structures have inherent characteristics, serving to reinforce or weaken ideology; a struggle for hegemony can thus be played out within the framework of public administration.

The study is based on an interest in the relation between governance structures and ideology. This does not mean that the results will generate the conclusion that a particular kind of governance model always produces a certain ideological outcome. Governance is not considered to be determined for a specific effect or consequence but as a social phenomenon, and actors are not equated with their structural or organizational identities and positions. This premise means that contextual structures and conditions constitute the foundations for agency, while agency can reproduce or change these structures and conditions (Archer, Citation1995, p. 158). There is room for actions within a social structure, and these actions can produce changes, reinforcements or displacements in it.

Methods for analysing the ESF GE policy in Spain and Sweden

This article compares ESF’s GE governance structures in Sweden and Spain. Despite different national contexts and histories, during the analysed time period, both countries were at the forefront of GE policy. At the same time, their ESF support structures were designed differently (Commission, Citation2016). Generally, during the 2000–2006 programming period and initially during the 2007–2013 period, Spain had a certain focus on GE policies and introduced new laws aimed at increasing women’s rights in several policy areas. These entailed a shift from Spain’s conservative and authoritarian history (Magone, Citation2018, p. 20; Bustelo, Citation2016) and from being regarded as one of the least equal countries in the EU to climbing the EU’s lists and indices that measured GE levels in the member states (León, Citation2011). Historically, Spain has a weak institutionalization of GE policies and a strong women’s movement (Threlfall, Citation2010). In contrast, Sweden has been described as the world’s most equal country, and it ranks highly, topping both EU and other international ratings. The institutionalization of GE policies has historically been strong with a high degree of “state feminism” (Sainsbury, Citation2004).

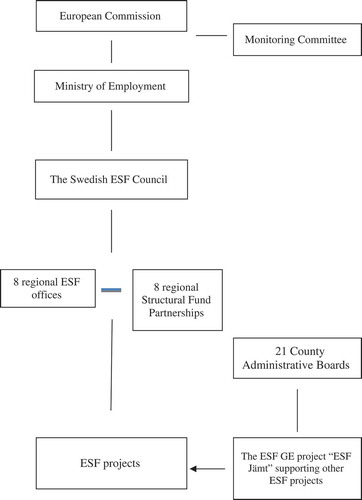

Regarding engagement with the structural funds, Spain is a recipient of major funding with a total of ESF allocation of EUR 11,4 billion during the time period studied. Sweden is a recipient of minor funding with a total of ESF allocation of EUR 1,2 billion during the same years (Commission, Citation2012b; Ruiz, Citation2008; Schratzenstaller, Citation2013; Swedish ESF Council, Citation2013). In 2007–2013, the two member states chose to develop prioritized organizational structures for the ESF’s GE policy. These were specifically created within the framework of the national ESF administration, with the application of a range of methods, work processes and control systems ().

In Sweden, actors from the public, private and voluntary sectors collaborated in networks on ESF project financing decisions, as well as auditing and other governance activities. The regional Structural Fund partnerships played a particularly important role and consisted of elected representatives of municipalities and county councils, as well as representatives of labour market organizations, such as employment agencies, universities and colleges, and business and interest organizations. They decided on project funding and had a formal impact on the economic and the substantive conditions for implementing the EU regional policy at the Swedish regional and local levels (SFS Citation2007: 459). The GE work was externally directed and targeted the ESF projects, where participation in GE activities was voluntary. The County Administrative Boards (CAB) project ESF Jämt provided GE support to the ESF projects.

In contrast, the Spanish governance model was organized hierarchically, with fewer decision-making actors and with the GE work directed internally and centrally towards the ESF administration employees. Participating in GE activities was mandatory for these ESF administrators at the national level. Spain has 17 autonomous regions, each with its own ESF programme. However, all regions are subject to the nationally established GE criteria, and the support structure for GE was centralized in this sense. A group of ESF administrators, who called themselves the ESF GE group, initiated the GE work together with the national authority the Women’s Institute. They were in charge of GE support, directly addressed to the ESF employees. In conjunction with the notable development in Spain’s GE policy at the time, the differences in Spain’s and Sweden’s respective designs of the ESF’s GE support structure justify the comparison between the countries.

Qualitative methods were used in tandem with a rich body of empirical material based on interviews and policy documents. The empirical material was addressed with an ideology analysis (Eagleton, Citation2007). This study explored the relationship between governance and ideology, consisting of an interaction among the analytical levels of actors’ assumptions, organizational processes and the political environment. The ideological (substantive) dimension of the GE policy was operationalized by actors’ assumptions about GE based on three main components: (a) what GE is, its causes and effects; (b) how GE policy should be organized within the ESF policy; and (c) what options for action are possible in the ESF policy context. The concept of the governance structure was operationalized by distinguishing between organizational forms and control techniques. By organizational form I refer to the formal structure of positions and actors in an organization and their respective relationship to each other through, for example, delegation of tasks and pronounced responsibilities. By control techniques I refer to the measures that are used to control and govern, such as formalization of tasks through rule-based regulation, preparation and use of audit systems, collaboration activities, mandatory activities etcetera.

The empirical analysis drew on policy documents on ESF regulation at European (16), national (12) and regional level (9) and on 21 interviews with key actors involved in the 2007–2013 ESF’s GE policy in Sweden and Spain. The ESF organization and the support structure were considerably more centralized in Spain () than in Sweden (). The analysis of the Spanish case was therefore based on a smaller number of interviews. Less people were involved in formulating the definition of and organizing the GE policy in Spain. In total, 14 interviews were conducted at the national level and in two regions in Sweden. In Spain, there were seven interviews in total and documents from the national level and five regions. The website that was developed to publish the presentations in the regional meetings initiated at the national level to engage the Spanish regions was also included in the analysis.

The following section starts with an analysis of the relationship between how the ESF’s GE policy was organized and interpreted Sweden, followed by an analysis of Spain. On one hand, it analyses if and how assumptions about gender and GE affected the organizing of the policy, and on the other hand, if and how the organizing influenced and helped to produce dominant interpretations of gender and GE within the ESF organizations. Based on the analysis, a discussion of the options for actions related to governance structures is outlined.

Governance and ideological content in the Swedish ESF GE policy

In Sweden, the ESF GE policy was mainly anchored in an ideological interpretation of GE as a promotion of resource efficiency, i.e. supported the Commission´s interpretation of GE in ESF. Although there were actors representing a contrary interpretation of GE, the organizational form and control techniques contributed to making the economic growth perspective dominant.

Ideological assumptions about the ESF’s GE policy

During the 2007–2013 period, the goal of the Swedish ESF was to strengthen economic development through promoting skills and increased labour supply:

A potential labor shortage could hamper companies’ opportunities to grow and is thus a threat to Sweden’s economic development. Efforts in many policy areas are required to prevent such development. It is about better utilizing the existing workforce and increasing labor force participation (Swedish ESF Council, Citation2007, p. 28).

Accordingly, the gender perspective was mainly related to a discussion on the gender-segregated labour market. A more concrete definition of the perspective was left open in the national operational programme. During the interviews at the national level, a diffuse definition of GE policy emerged, floating between a growth perspective and a social perspective. One interviewee intertwined the perspectives as follows:

If you work with an approach that is equitable for everyone, I think it contributes to better growth. It is related, I mean. If you have a rights perspective, I think it will promote sustainable growth. (Swedish ESF Council, management representative.)

GE was more clearly defined within a discourse on economic efficiency and profitability at the regional level, where resource efficiency was highlighted as a core value:

[GE] is about improving resource utilisation in the economy. We have lower employment rates among women, while in some cases the absolute unemployment rate is higher among men. I believe that the labour market needs to be able to make non-gender-stereotyped recruitments; it is better to recognise all skills than just half. This would lead to lower unemployment and better resource utilisation. It’s a good deal. (ESF administrator, Region B.)

This interpretation largely corresponded to the overall formulations in the EU’s regional and social fund policies (Brine, Citation2002; Tomé, Citation2013). Another regional ESF administrator (Region A) linked the GE concept with a discussion on a regional development perspective (i.e. human capital and growth):

If you are striving for a good foundation for development and growth within a region, then you must involve everyone regardless of gender. You shouldn’t strive for a single-sex labour market; if there is to be development, then it must be of both sexes.

What does “development” mean?

Economic growth. From an economic growth perspective, you should involve both sexes. You should endeavour to have the whole population as your recruitment base.

At the project level, the CAB performed a central role in developing GE implementation methods. During the initial stage of the programming period, contradictions occurred between the CAB’s definition of GE, promoting a democratic perspective, and the regional ESF offices’ definition from an economic growth perspective. The CAB subsequently adapted the interpretation of the ESF Council and started workshops for ESF projects on how to integrate a gender perspective with a profitability perspective (ESF Jämt & Tema Likabehandling, Citation2011).

The purpose of the ESF’s GE policy was initially vague but was further defined as more actors became involved, i.e. the organizational form (network) helped to produce a dominant ideological assumption. Although some actors expressed alternative interpretations of the GE concept, these had little impact. The next section discusses how the organizational form and the control techniques contributed to this situation.

Organizational form and control techniques

Overall, control techniques, such as quantitative measurements and consensual decision making, characterized the governance of the ESF’s GE policy. The EU’s collaborative requirements permeated Swedish ESF policy, and the business sector occupied significant positions in the governance structure at both national and regional level.

The Swedish ESF Council formally initiated the organizing of the GE policy at the national level. At first, there was no clear definition of GE in relation to the ESF, but the responsibility for defining the GE concept was relocated among the actors in the organization. According to the respondents from both national and regional levels, the actors had no organic collaboration or dialogue. In the absence of dialogue, the focus was directed at administration. One respondent argued that the lack of a substantive framework for the GE perspective had negative effects in that only quantitative aspects were emphasized:

Was this a democratic issue, a social issue, or […] a specific business issue? When you have not decided at [a national] level what you want to do and why, then that uncertainty percolates down to the project, and thus, the only thing that can be done is to report the quantitative [dimension of GE]. (Monitoring Committee member.)

Similarly, one respondent observed that the purpose of a gender perspective was unclear throughout the internal ESF organization and that “there were no structures at all for internal ESF gender equality” (ESF administrator, Region A). While the formal GE work was externally directed towards the ESF projects, there was no clear perception on how to organize the GE policy within the ESF administration.

At the regional level, an economic perspective eventually defined the overall interpretation of GE, emphasizing economic growth. One reason why the regional level became important for the interpretation process was delegated decision-making power to regional public–private Structural Fund partnerships. The partnerships were legitimized based on the idea of local connection. However, the respondents from the Swedish ESF Council described the partnerships as lacking the knowledge or interest to prioritize the “right” projects from a gender perspective, leading to GE projects’ failure to obtain funding. One interviewee provided a picture of the relationship between the ESF managing authority and the regional partnerships when planning the previous programming period:

The partnerships were new actors. We had some trouble finding the roles, what they were going to do, what we were going to do. Entering deeply into gender mainstreaming, they would have killed us. […] And it is important to say that we received a lot of criticism from the market, from the partnerships, because we made demands on GE. It was pretty tense. (Swedish ESF Council, manager.)

The roles were undefined, and the tensions among the actors meant that the Swedish ESF Council did not discuss the meaning of the GE policy or responsibilities with the partnerships. One administrator from an ESF office (Region B) expressed frustration regarding the partnerships: “I know that saying so is tantamount to sacrilege, but it would have been quite nice to avoid the partnership at times”. However, he continued, “I guess that’s what democratic transparency is like”. Although the business sector was represented in the public–private partnerships, the legitimacy of the partnerships flowed from a democratic perspective, making it difficult to criticize them.

The regional ESF offices had at least some contact with the partnerships, in contrast to the CAB who described the partnerships as follows:

The partnerships were conspicuous by their absence; after all, they were like the deity that makes the decisions but is not present in any way. Do they even know about gender equality? The teamwork was not there at all. (Co-worker at the CAB/ESF Jämt.)

Imagine splurging all those millions over all these years on this giant [external] support organisation for GE, which is fantastic and unique, I believe. There are lots of associates here. Who makes sure that it is [kept together]? I don’t know. (Co-worker at the CAB/ESF Jämt.)

At the regional level, the GE perspective tended to end up in the shadows for the benefit of other regional development issues, where the agenda was to some extent perceived as predetermined. The respondents described the relationships among the actors at all levels as characterized by distance and closed processes. With the lack of explicit conflicts and communications the legitimation of GE policy, based on assumptions about its promotion of economic growth, emerged as natural especially at the regional level. Moreover, the lack of communication revealed that GE work was integrated into a bureaucratic-administrative structure with an emphasis on administration and a focus on quantitative measurements. As stated by Alnebratt and Rönnblom (Citation2016) and Stivers (Citation1993), the attention to quantitative measurements in public administration tends to result in the subordination of the gender perspective. And as argued by Hudson and Rönnblom (Citation2007) and Isaksson (Citation2010), the consensual decision-making process within regional partnerships results in a depoliticized approach to GE issues, also contributing to the subordination of the GE policy.

In addition to the undefined division of roles, the statutory decision making within the partnerships affected the strength of the GE policy. The partnerships had to make decisions by consensus. One respondent from the partnership in Region A believed that the gender perspective was perceived as important and for him personally GE was about “not categorizing people” (member of the Structural Fund partnership, Region A) and allowing both women and men free choices at work. At the same time, he believed that this perspective did not ultimately permeate the partnership’s decision making. The members had different geographical anchorage and came from various sectors. Accordingly, they did not usually agree on the decisions. The conflicts were often due to members wanting more fund assets to be allocated to their own local areas, contributing to economic development. Combined with the requirement for consensus, these tensions resulted in the non-prioritization of the gender perspective:

There cannot be conflicts, so in the end, there was a lot of trade-offs. And when you embark on such a process, the gender perspective drops out. (member of the Structural Fund partnership, Region A.)

The representation of economic interests in partnerships hampered the impact of the gender perspective. This result is supported by previous studies arguing that private actors’ involvement in public governance tends to compromise social values, such as GE (e.g. Prügl & True, Citation2014).

Governance and ideological content in the Spanish ESF GE policy

In Spain, the ESF GE policy was mainly anchored in an interpretation of GE as a matter of social justice and democracy, i.e. representing an alternative ideological interpretation than promoted by the Commission and at the same time challenging conservative perceptions of GE work within the national ESF administration. With the active use of a hierarchic organizational form and mandatory control techniques, the social justice perspective had impact during the period 2007–2013.

Ideological assumptions about ESF’s GE policy

In Spain, the development of the GE policy was initiated by a smaller group of civil servants, who called themselves the “gender equality group” (GE group), in the management of the national ESF administration. The group explicitly defined the GE concept as departing from the focus on social rights and justice (DGFC, Citation2009; Women´s Institute, Citation2010a, Citation2010b). The gender perspective was related to the ESF policy and the labour market conditions; however, an effort was made to relate GE to other policy areas beyond the ESF’s, such as gender-related violence and fair living conditions for children and young people. Representatives from the GE group explained that equal rights constituted the main motive for starting GE work. One of these officials emphasized GE as a question of equal legal rights. ESF becomes a tool for achieving social change in the transition towards a just society:

I studied law, so in my opinion, equality is a constitutional right. In so far as it is a constitutional right, you have to implement it in every step, like other rights. Inequalities between men and women are so visible in Spanish society. […] The Structural Funds are part of life, like the rest of the policies, and they are equally necessary. (member 2, ESF GE group, managing authority.)

The ESF is a labour market instrument for merging the economic aspects of growth and the social aspects of GE, according to the EU’s writings on the overall objective of increased labour supply (Commission, Citation2012a). The Commission stressed that a more competitive labour market would be achieved, inter alia, through increased GE (i.e. the use of human capital). As stated, this logic reflected the Swedish ESF organization, where the aim of GE policy was interconnected with a discussion of labour supply and growth. However, in the Spanish case, this interpretation did not carry equal weight but was perceived as a possible contradiction:

I think the political and the economic interests are not always on the same side regarding the gender issues, but I think [GE] is a question of justice (member 3, ESF GE group, managing authority).

The respondent assumed that GE did not directly constitute an endeavour to achieve both economic growth and social justice. Instead, these two interpretations potentially contrasted, with the profitability perspective subordinated to the social rights perspective. The expected effects of a successful GE policy were described as constituting an overall social change where the ESF could contribute through a resource allocation between social groups secured by the ESF administrator’s assessments and reviews of projects. The primary interpretation of the ESF’s GE policy as a promotion of social rights and justice differed from the Commission’s formulations and (as shown in the next section) the dominant assumptions in the organizational environment within the Spanish public administration, which expressed conservative assumptions about gender and resisted the GE work.

Organizational form and control techniques

In Spain, the ESF was less organized by the Commission’s principle of partnerships (Bache, Citation2008). According to one respondent, the GE group could initiate GE work because the ESF managing authority was located within the Ministry: “ESF is close to the Ministry […]; we have some power to press and push” (member 3, ESF GE group, managing authority). The substantive meaning of GE was clearly defined by this group at this level, with no valid opportunities for other actors to contribute alternative interpretations. The GE policy was addressed to the ESF administrators and included mandatory activities and requirements for all employees at the national level. The hierarchical organization and rule-based approach became important in introducing a gender perspective in the ESF:

It’s not about saying, ‘take the gender perspective into account, blah blah blah’. We wanted facts and results. (member 3, ESF GE group, managing authority.)

The respondent expressed the belief that change would occur as a result of the compulsory use of new work methods. The varied ideological interpretations of GE within the administration also explained why it was considered important to arrange shared seminars and workshops:

Are there different understandings within the ESF regarding the concept of gender equality?

Member 2, ESF GE group, managing authority: Yes. And that’s why it’s important to have regular seminars, courses and discussions about it.

The ESF officials promoting GE assumed that they would face resistance and questioning from their ESF colleagues, and the hierarchical model with mandatory activities was used as a proactive response:

So, there was a lot of resistance, which we knew was going to happen, but we didn’t care (member 1, ESF GE group, managing authority).

The mandatory internal activities were effects of the expected resistance, and the decision-making process followed a formal hierarchical structure. Furthermore, delegation order, control and auditing were performed centrally in the organization. The organizing and activities of the ESF’s GE policy were used explicitly to establish a centrally defined GE policy. The feminist critique had focused on the traditional bureaucracy’s tendency to reproduce unequal social relations, particularly patriarchal relations (cf. Ashcraft, Citation2001; Bologh, Citation1990; Ferguson, Citation1984; Stivers, Citation1993). However, the Spanish case showed that a hierarchical organization with mandatory and rule-based control techniques can be useful for GE work that challenge established assumptions about gender relations. The governance structure helped to reinforce ideological assumptions of the GE group, while simultaneously contradicting dominant ideological assumptions in the administration. There are several explanations as to why this was possible. One is that the dominant ideology already had some cracks. In the studied period, Spain’s political regime, led by the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party, instituted new laws aimed at changing gender structures in society. Additionally, the EU’s GE requirements for the ESF were used to legitimize GE work at the national level. It was also crucial that the GE group had the opportunity to meet and discuss how to organize the GE work and to lobby the Ministry. Thus, the existing organizational structure enabled this group to pressure the central administration. Nevertheless, in the wake of the economic crisis and the conservative wave of Spanish politics, the ESF’s GE work was dismantled by the end of the 2007–2013 programming period.

The GE policy was defined by and directed towards the national level, where the analysis was primarily conducted. There was no delegation of definitions or work methods to the regional level. The regions were offered access to method materials, guidelines and joint meetings, and the national administrators set GE requirements in communication with the regions.

Conclusions

Inherent mechanisms in administrative processes have ideological consequences. At the same time, the interaction between governance structure and ideology appears in different shapes in the Swedish and Spanish case. As stated in previous research, the EU’s GE policy is defined within the tension between social and economic growth perspectives. This study showed that the national governance structures contributed to the variations in the attention to the ESF’s GE policy in Sweden and Spain during the 2007–2013 programming period. Sweden corresponded better to the Commission’s definition of GE and the EU’s ideas of governance, while specific national conditions for GE seemed to have primarily influenced its definition and implementation in Spain (cf. Sanchez Salgado, Citation2013).

The organizational form and control techniques characterizing the policy process in Sweden supported the reproduction of assumptions promoting an economic growth perspective, thus limited the promotion of GE as an issue of social power relations. This was due to the lack of communication channels and the interpretive prerogatives dominating the decision-making process where public–private partnerships prioritized growth-investment ESF projects. The lack of dialogue prevented alternative ways of interpreting and reduced possibilities for redefining the political content promoted by the EU. In this sense, the complex coordination limited the opportunities for discussing substantive political aspects and shaped an informal hierarchy between actors (cf. Davies, Citation2011). Policy networks, with participating business sector actors, tasked with implementing an overall growth policy thus tends to promote an economic growth-oriented definition of GE.

Another conclusion is that bureaucratic control techniques, such as management by regulation, tend to override the governance of policy goals in cases with no clear definition of the policy content. This was most visible in the Swedish case, where no distinct initial definition of GE permeated the actors’ collaboration. Initially, there was no substantive definition, resulting in a focus on auditing and accounting. However, in contrast to previous feminist studies on bureaucracy, this study showed that bureaucratic governance characteristics can be beneficial for policy change in relation to issues of informal power structures (e.g. GE), especially when GE policies lack legitimacy. In the Spanish case, the governance structure promoted discretionary power for civil servants. Control techniques such as mandatory and confrontational activities also produce open conflicts and discussions, i.e. politicizing GE politics. Therefore, hierarchy as an organizational form does not automatically imply that bureaucratic control techniques push away substantive policy aspects. Rather, feminist officials can use bureaucratic governance characteristics to establish and define GE politics (cf. Ferguson, Citation1984; Pringle, Citation1989; Stivers, Citation1993; see also Weber, Citation1978; Graeber, Citation2015).

Policy change is promoted by the possibility of discussions on policy content. At the same time, the results showed such discussions as insufficient to create long-term changes; rather, institutional, economic and political contexts had considerable impact. Some actors, in both Sweden and Spain, opposed established assumptions about GE, but whether these affected the interpretation process was partly due to the governance structures. It was consequently possible to challenge assumptions and beliefs, but the reason for the lack of change was found at a non-discursive level. What is important is that neither a pronounced requirement for change nor governance proved enough for a long-term effect. The conditions for lasting change were instead due to several contextual aspects. This result calls for more feminist research on the profound interaction between governance and broader institutional, economic and ideological processes. Secondly, it points to the importance of feminist scholars, who seek to understand GE policy change and implementation, understanding governance processes within the public administration.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors for helpful and constructive comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Vanja Carlsson

Vanja Carlsson is a researcher and teacher at the School of Public Administration, University of Gothenburg. In her thesis from 2019 she investigates the Swedish and Spanish implementation of the gender equalitp policy within the European Social Fund. Her theoretical interest involves the relationship between public governance models and ideological content of politics.

References

- Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender & Society, 4(2), 139–158.

- Ahrens, P., & Callerstig, A.-C. (2017). The European Social Fund and the institutionalisation of gender mainstreaming in Sweden and Germany. In H. Macrae & E. Weiner (Eds.), Towards gendering institutionalism (pp. 69–97). London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Allwood, G. (2013). Gender mainstreaming and policy coherence for development: Unintended gender consequences and EU policy. Women’s Studies International Forum, 39, 42–52.

- Alnebratt, K., & Rönnblom, M. (2016). Feminism som byråkrati [Feminism as bureaucracy]. Stockholm: Leopard Förlag.

- Archer, M. (1995). Realist social history: The morphogenetic approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ashcraft, K. L. (2001). Organized dissonance: Feminist bureaucracy as hybrid form. Academy of Management Journal, 44(6), 1301–1322.

- Bache, I. (2008). Europeanization and multi-level governance. Cohesion policy in the European Union and Britain. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Bologh, R. (1990). Love or greatness. Max Weber and masculine thinking – A feminist inquiry. London: Unwin Hayman.

- Booth, C., & Bennett, C. (2002). Gender mainstreaming in the European Union. Towards a new conception and practice of equal opportunities? The European Journal of Women´s Studies, 9(4), 430–446.

- Brine, J. (2002). The European Social Fund and the EU. London: Sheffield Academic Press.

- Bustelo, M. (2016). Three decades of state feminism and gender equality policies in multi-governed Spain. Sex Roles, 74(3), 107–120.

- Büttner, S. M., & Leopold, L. M. (2016). A ‘new spirit’ of public policy? The project world of EU funding. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 3(1), 41–71.

- Carlsson, V. (2019). Jämställdhetspolitik och styrformens betydelse [Gender equality policy and the importance of governance models] (Diss). University of Gothenburg.

- Carlsson, V., & Mukhtar-Landgren, D. (2018). Styrning genom frivillig koordinering? [Governing by voluntary coordination?]. Statsvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 2018(3), 137–161.

- Commission. (2007a). European Social Fund. 50 years investing in people. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Commission. (2007b). Cohesion policy 2007–13. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Commission. (2008). Working for the regions. EU regional policy 2007–2013. Luxembourg: Publications Office.

- Commission. (2012a). European Social Fund investing in people. What it is and what it does. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Commission. (2012b). Spain and the European Social Fund. Brussels: Author.

- Commission. (2016). ESF ex-post evaluation synthesis 2007–2013. Brussels: Author.

- Davies, J. (2011). Challenging governance theory. Bristol: Policy Press.

- DGFC. (2009). Dirección general de fondos comunitarios. In Guia metodologica para la evaluacion estrategica tematica de igualdad de oportunidades entre hombres y mujeres [Methodological guide for the thematic strategic evaluation of equal opportunities between men and women] (pp. 1–54). Madrid: Secretaria general de presupuestos y gastos.

- Diefenbach, T., & Todnem By, R. (2012). Bureaucracy and hierarchy – What else!? In T. Diefenbach & R. Todnem By (Eds.), Reinventing hierarchy and bureaucracy (pp. 1–27). Bingley: Emerald Books.

- Eagleton, T. (2007). Ideology. London: Verso.

- EIGE. (2018). Gender budgeting. Mainstreaming gender into the EU budget and macroeconomic policy framework. Luxemburg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Elomäki, A. (2015). The economic case for gender equality in the European Union: Selling gender equality to decision-makers and neoliberalism to women´s organizations. European Journal of Women´s Studies, 22(3), 288–302.

- ESF Jämt & Tema Likabehandling. (2011). Jämställdhet och lönsamhet – Hur hänger det ihop? [Gender equality and profitability – How is it related]. Örebro: Invitation to workshop.

- Ferguson, K. (1984). The feminist case against bureaucracy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Graeber, D. (2015). The Utopia of rules. Brooklyn: Melville House.

- Hawkes, D. (2003). Ideology. London: Routledge.

- Hooghe, L. ( red.). (1996). Cohesion policy and European integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hudson, C., & Rönnblom, M. (2007). Regional development policies and the constructions of gender equality: The Swedish case. European Journal of Political Research, 46(1), 47–68.

- Isaksson, A. (2010). Att utmana förändringens gränser [Challenging the limits of change]. Lund: Diss Lund University.

- Kantola, J., & Squires, J. (2012). From state feminism to market feminism? International Political Science Review, 33(4), 382–400.

- León, M. (2011). The quest for gender equality. In A. M. Guillén & M. León (Eds.), The Spanish welfare state in European context (pp. 59–76). Surrey & Burlington: Ashgate.

- Lewis, J., & Giullari, S. (2005). The adult worker model family, gender equality and care. Economic and Society, 34(1), 76–104.

- Lombardo, E. (2008). Gender inequality in politics. Policy frames in Spain and the European Union. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 10(1), 78–96.

- Lombardo, E., & Meier, P. (2006). Gender mainstreaming in the EU: Incorporating a feminist reading? European Journal of Women’s Studies, 13(2), 151–166.

- López-Santana, M. (2006). The domestic implications of European soft law: Framing and transmitting change in employment policy. Journal on European Public Policy, 13(4), 481–499.

- Magone, J. M. (2018). Contemporary Spanish politics. New York: Routledge.

- Marks, G. (1993). Structural policy and multi-level governance in the EC. In A. Cafruny & G. Rosenthal (Eds.), State of European community (Vol. 2, pp. 391–409). Boulder Colorado: Lynne Rienner and London: Logman.

- Olsson, J. (2003). Democracy paradoxes in multi-level governance: Theorizing on structural fund system research. Journal of European Public Policy, 10(2), 283–300.

- Piattoni, S. (2010). The theory of multi-level governance. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Pringle, R. (1989). Secretaries talk. London: Verso.

- Prügl, E., & True, J. (2014). Equality means business? Governing gender through transnational public-private partnerships. Review of International Political Economy, 21(6), 1137–1169.

- Rehmann, J. (2013). Theories of ideology. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

- Rhodes, R. A. W. (1996). The new governance: Governing without government. Political Studies, 44(4), 652–667.

- Rönnblom, M. (2009). Bending towards growth: Discursive constructions of gender equality in an era of governance and neoliberalism. In E. Lombardo, P. Meier, & M. Verloo (Eds.), The discursive politics of gender equality (pp. 105–120). London: Routledge.

- Ruiz, C. (2008). New methods and results in measuring the efficiency of EU funds: The Spanish case. Society and Economy, 30(2), 245–257.

- Sainsbury, D. (2004). Women’s political representation in Sweden: Discursive politics and institutional presence, Scandinavian Political Studies, 27(1): 65–87.

- Sanchez Salgado, R. (2013). From ‘talking the talk’ to ‘walking the walk’: Implementing the EU guidelines on employment through the European Social Fund. European Integration Online Papers, 17(2), 1–26.

- Schratzenstaller, M. (2013). The EU own resources system. Intereconomics, 48(5), 303–313.

- SFS 2007: 459. Swedish Structural Fund Partnership Act.

- Smith, M., & Villa, P. (2010). The ever-declining role of gender equality in the European employment strategy. Industrial Relations Journal, 41(6), 526–543.

- Squires, J. (2007). The new politics of gender equality. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Stivers, C. (1993). Gender images in public administration. New York: SAGE Publications.

- Stratigaki, M. (2004). The cooptation of gender concepts in EU policies: The case of reconciliation of work and family. Social Politics, 11(1), 30–56.

- Swedish ESF Council. (2007). Nationellt strukturfondsprogram för regional konkurrenskraft och sysselsättning (ESF) 2007–2013 [National Structural Funds program for regional competitiveness and employment (ESF) 2007–2013]. Stockholm: Swedish ESF Council.

- Swedish ESF Council. (2013). Socialfonden i siffror [Social fund in numbers]. Örebro: APeL Forskning och utveckling.

- Threlfall, M. (2010). State feminism or party feminism? Feminist politics and the Spanish Institute of Women. In M. L. Krook & S. Childs (Eds.), Women, gender and politics: A reader (pp. 227–233). New York: OUP.

- Tomé, E. (2013). The European Social Fund: A very specific case instrument of HRD policy. European Journal of Training and Development, 37(4), 336–356.

- Trubek, D. M., & Trubek, L. G. (2005). Hard and soft law in the construction of social Europe. European Law Journal, 11(3), 343–364.

- True, J. (2009). Trading in gender equality. In E. Lombardo, P. Meier, & M. Verloo (Eds.), The discursive politics of gender equality: Stretching, bending and policymaking (pp. 121–137). London: Routledge.

- Verschraegen, G., Vanhercke, B., & Verpoorten, R. (2011). The European Social Fund and domestic activation policies. Journal of European Social Policy, 21(1), 55–72.

- Walby, S. (2004). The European Union and gender equality: Emergent varieties of gender regime. Social Politics, 11(1), 4–29.

- Weber, M. (1978). Economy & society. (G. Roth & C. Wittich, ed). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Women´s Institute. (2010a, May 13–14). Jornada de capacitación la igualdad de oportunidades entre mujeres y hombres en los fondos estructurales y el fondo de cohesion 2007–2013 [Training conference on equal opportunities between women and men in the structural funds and the 2007–2013 cohesion fund]. Presentation, Madrid.

- Women´s Institute. (2010b, May 13–14). Prioridades futuras para la UE en el area de la igualdad de género [Future priorities for the EU in the area of gender equality]. Presentation, Madrid.

- Woodward, A. (2012). From equal treatment to gender mainstreaming and diversity management. In G. Abels & J. M. Mushaben (Eds.), Gendering the European Union (pp. 85–103). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Zartaloudis, S. (2015). Money, empowerment and neglect –The Europeanization of gender equality promotion in Greek and Portuguese employment policies. Social Policy & Administration, 49(4), 530–547.