Abstract

Development agencies which address climate change adaptation (CCA) are increasingly adopting human rights-based approaches (HRBAs) as central to their policies and principles. What, however, does that entail in practice? This qualitative case study examines whether and how development NGOs in Cambodia understand and apply HRBAs to CCA programming. We explore the themes of participation, transparency, accountability, and non-discrimination, and examine the experiences and implications of these efforts. An HRBA is a political agenda that is often assumed to challenge a dominant discourse which emphasises technical solutions and sidesteps structural factors of power, vulnerability, inequality, and responsibility. Despite agency commitments to HRBAs, however, this perspective is only cautiously being applied to climate change due to hesitance to critically engage in politics and governance. Linking CCA and human rights would require anchoring efforts within broader efforts related to the participation of vulnerable populations in national development, pressure for greater transparency, accountability of duty bearers, and spotlighting discriminatory governance practices. An HRBA, as currently perceived and applied, has yet to contribute to breaking down the ‘silos’ and other incentives to treat CCA as a technical concern rather than as an impetus for transformational change. Changes in Cambodia’s political landscape may intersect with the global HRBA discourse to challenge dominant development approaches.

Introduction

Climate change (CC) is bringing to the fore critical issues about the linkages between human rights and the environment. Responses to intensified ‘natural’ hazards and increasingly uncertain weather conditions are coming to be recognised as reliant on safeguarding the rights of vulnerable populations. In many countries, civil society is positioning itself to represent at-risk rights holders, and engaging in two ways. First, advocacy is being used to put pressure on duty bearers in local and national governments to address risks posed by CC. Second, many are engaged directly in field-level programming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and vulnerability to the effects of CC. These efforts can generate tensions, since national economic development policies reflect a broad range of concerns, many of which are not related to either climate risks or the perspectives and vulnerabilities of rights holders – and may actually exacerbate climate risk.

Globally, non-government organisations (NGOs)Footnote1 are adopting policies that call for human rights-based approaches (HRBAs), which are designed to build on participation, transparency, accountability, and non-discrimination as a way to increase the power and voice of these vulnerable populations and put pressure on duty bearers. The intention is to make explicit the political nature of development, including climate change adaptation (CCA) and mitigation.Footnote2 Commitments to HRBAs may challenge those climate policy discourses which emphasise ‘win–win’ technical solutions and sidestep structural factors of power, vulnerability, inequality, and responsibility. This study specifically explores how international and local NGOs frame their understandings of rights and responsibilities surrounding CCA in Cambodia, and the key tensions that arise or are avoided. Although there is growing awareness and discourse about the interface between CC and human rights, there has been little systematic investigation of what a rights-based approach to CC would actually entail in practice. This study explores how these issues are playing out in Cambodia, with an emphasis on:

the practical implications of HRBAs in a CCA context (i.e. activities and arrangements), particularly with regard to NGO strategies to interact with state actors;

how the distribution of responsibilities among different actors is conceptualised, most notably the range of ‘duties’ that are assumed to rest with different duty bearers; and

the prevailing constraints and opportunities to realising HRBAs, including limits to the incentives and capacity of local duty bearers to address structural vulnerability.

We examine how NGOs in Cambodia are addressing and implementing right-based approaches to CCA and mitigation, and what the experiences and implications are from these efforts.

Methodology

The authors utilised qualitative methods for this study. The research is ultimately exploratory, and the authors sought to illuminate how governmental and NGO actors engaged in either human rights or CC-related efforts understood and expressed the linkages between CCA and human rights – both of which are broad terms supported by diverse (and, indeed, contested) programmes and policies. This section will review the study’s design; the research sample and site, data collection, analysis, and synthesis; and the limitations of the data.

Research design

The data for this study were drawn from a series of in-depth, open-ended interviews conducted in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. The interview approach prompted participants to reflect on their own understandings of the concepts in question, and whether or how they directly applied within their own work, or in Cambodia generally. Throughout the fieldwork, the authors engaged in an iterative process of building and testing explanatory hypotheses with interviewees. Working hypotheses were developed through interview feedback or documents and then explored in further interviews and literature review. This ongoing process continued through to the analytical phase of the research.

Research sample and site

Sample size and variability in qualitative research vary considerably (Sobal, Citation2001), and data were collected until the point of saturation, that is, when new conversations became repetitive rather than revelatory. A total of 25 separate interviews were conducted in Phnom Penh over a two-week period in August 2014. Sampling for the interviews was purposive, and based on both judgement and theoretical considerations. Most (16) involved representatives of NGOs engaged in CCA and/or HR-related issues; the remainder included individuals drawn from government agencies, multilateral organisations, knowledgeable consultants and academics, and other relevant institutions (e.g. a public interest law firm and a CBO support network). Interviews were usually with a single representative; however, some included two or more people from a single agency. All but one interview was conducted in English. Relevant agencies were identified through their profile in CC and/or human rights, as well as through ‘snowball’ techniques. Nearly every individual or agency that was approached granted an interview.

Data collection, analysis, and synthesis

Open-ended questions invited interviewees to present their work on CC, sustainable development, and/or human rights, and reflect on the themes of the study. Probing questions were utilised to bring out certain themes in more detail, for example, whether and how HRBAs had been applied to advocacy strategies. Detailed notes were taken of each interview by the two authors; these were reviewed, verified, and referred to throughout data analysis and report writing. It should be noted that direct quotes which appear in this paper are reconstructed from the authors’ written notes and are thus paraphrases. The authors collaborated closely in identifying key themes that emerged from the interviews.

Limitations of the data

The authors are confident in the integrity of the data and that it represents a valid representation of the experiences and opinions from across a spectrum of professional stakeholders, which necessarily implies an elite group. Nevertheless, there are important limitations. This study was conducted under time and resource constraints, which limited the scope of data collection. The authors did not, for example, review various agencies’ portfolios or visit their field sites. Data consist entirely of interviews, complemented by literature review. It did not include an independent analysis of NGO or government policies and programmes, nor input from community representatives themselves.

A second limitation is social response bias, that is, presenting the ‘right answer’ rather than frank viewpoint. Some interviewees were careful to only focus on what their agency was achieving or to promote their institution’s official positions. There were noticeable differences between expatriate and Khmer informants; the latter tended to be more comfortable focusing on their own work and hesitant to express critical analyses of ‘meta’ issues. However, most interviewees were frank and forthcoming, and many of the most incisive insights came from Cambodians themselves. Overall, they confirmed Frewer’s (Citation2013) observation that NGO staff ‘navigated a precarious path between the demands of donors and what was possible and safe for them in their day-to-day existence’ (p. 106). Expatriates, by contrast, were often more analytic and critical about the ‘big picture,’ but lacked detailed examples and nuanced understandings of community-level programming and constraints.

Climate contexts in Cambodia

Cambodia is highly vulnerable to CC, due to high levels of poverty and inequality, demographic pressures, development trajectories that compound risks facing large sectors of the population, and the frequency of extreme climatic events. It has the world’s highest exposure to flooding, with an average of 12.2 per cent of the population affected annually (PreventionWeb, Citationn.d.). More than 70 per cent of Cambodia’s rice production loss between 2004 and 2008 was attributed to floods (Heng and Pech, Citation2009). Despite impressive economic growth surpassing 7 per cent per year since 2011, per capita GDP hovers around US$1000 per year. As of 2011, 43 per cent of the population subsisted on less than $2 per day (PPP). Despite high rates of internal migration, 80 per cent of the population remains rural (World Bank, Citation2014), and 65 per cent work primarily in agriculture (FAO, Citation2014).

The negative long-term effects of CC are being compounded by more immediate threats to the integrity of Cambodia’s natural environment, which are seen by communities as more urgent (CCCN, Citation2014). Cambodia has the third highest deforestation rate in the world: over 7 per cent of its forest cover was lost between 2002 and 2012 (Hansen et al., 2013, as cited by Milne and Mahanty, Citation2015). This alarming loss, coupled with threats to aquatic ecosystems (e.g. unsustainable fishing and upstream hydropower dams), is further compromising rural livelihoods and capacities to adapt to CC. In 2014, Standard and Poor’s ranked Cambodia’s economy as the single most vulnerable to the effects of CC worldwide (Kraemer and Negrila, Citation2014).

Cambodia is often pointed to as an example of a less-developed country (LDC) which has successfully mainstreamed CC into public policy. It has been described as ‘the “star” of CDM [clean development mechanism] among LDCs’ (Käkönen et al., Citation2014, p. 367), for example. Cambodia ratified the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1995, and it formulated one of the first LDC National Adaptation Programme of Action to Climate Change plans in 1996 (CCCN Citation2014). Today it actively partners with a number of international CC initiatives, including the UNFCCC and the Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PPCR). Funding to support these endeavours is significant: the PPCR’s budget for Cambodia, originally US$105 million, had climbed to US$240 million in grants and soft loans by 2013 (CCCN, Citation2014). An inter-agency National Climate Change Committee (NCCC), chaired by the Ministry of Environment, has been in place since 2006, and there are Climate Change Action Plans (CCAPs) for the national government and multiple ministries. The Cambodia Climate Change Alliance (CCCA) includes non-government actors while remaining ‘anchored in the government’ (Climate Change Department, Citation2014, para. 1) and, with international donor support, serves to strengthen the capacity of line ministries, local government, and non-governmental actors to address CC mitigation and adaptation (see, for example, Dahlgren et al., Citation2013).

Käkönen et al. (Citation2014) assert, however, that CC policy in Cambodia is ‘not principally grounded on country-level realities … [but] internationally driven and dependent on the existing international incentives and structures developed to support low-carbon development’ (p. 369). Our evidence concurs with this statement. Most interviewees (including some government representatives) described a nonchalance among policy-makers in Cambodia. They asserted that CC policy and programming have been top-down, and that duty bearers see adaptation and mitigation as a source of funding rather than as a meaningful responsibility. Considerable cynicism was expressed by most of those working in the non-government sector. As one Cambodian explained, ‘the government talks about climate change because there’s money, but it’s not meaningful.’

CC policy and programming presents many opportunities insofar as there is considerable overlap between it and overall sustainable development objectives. Nevertheless, as Spearman and McGray (Citation2011) have asserted, ‘not all development is adaptation and not all adaptation leads to development’ (p. 11). Käkönen et al. (Citation2014) demonstrate that climate and development objectives should also include the analysis of conflicts, tensions, and trade-offs; and Bours et al. (Citation2014a) have similarly asserted that

good adaptation is founded on an incisive consideration of how climate change interacts with issues of social justice … [and] approaches to adaptation should be grounded in a differentiated analysis of how vulnerability to climate change is compounded by poverty, power, and inequality. (p. 13)

The Cambodian state has selected aspects of CCA which are consistent with advancing other economic development goals, and omitted those that do not, however imperative they may be from a CC perspective. For example, CC is expected to bring about more unpredictable and extreme weather, and therefore greater need for disaster risk reduction and humanitarian efforts. Nonetheless, the duty to protect populations from disasters appears to be poorly understood or implemented in Cambodia. There is awareness of the links between CCA and disaster risk reduction among many NGOs, but these perspectives are not necessarily reflected operationally. The higher levels of government emphasise a ‘green growth’ model that focuses on harnessing economic opportunities and synergies wherein adaptation is assumed to be a ‘positive externality’ of economic development. This leads to a focus on those with growth potential, which implicitly downplays disaster risks or the priorities of the most vulnerable. For example, drought is used as a rationale for large-scale irrigation to farms to enable off-season double-cropping. This is presented as a disaster management initiative, even when it does not explicitly address risk and vulnerability among smallholders. Actors who are more concerned with underlying social and economic drivers of climate vulnerability appear to be largely excluded from mainstream CC efforts. Norman (Citation2014) has commented on the co-option of NGOs despite the rhetoric of participatory democracy; while uncritical enthusiasm for civil society ‘solutions’ continues in many official development platforms, academia has adopted a more critical eye. In some quarters critique has given way to cynicism and dismissiveness about NGOs in Cambodia as being donor-dependent and artificial. While it is easy to point to many failures, this discourse is replete with its own dangers, including further marginalisation of voices at the grass roots. Indeed, the Cambodian Government has directly and explicitly adopted this argument to marginalise agencies which adopt more confrontational approaches (see, for example, Rose-Jensen, Citationin press).

Cambodian agriculture policy reflects little awareness regarding the respective ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ of selected priorities as economic growth is seen to be universally beneficial. Large agricultural plantations (e.g. rubber) are expected to provide a welcome source of jobs in the countryside, despite evidence of increasing marginalisation of many rural smallholders. Moreover, there is little in-depth discussion on the implications of slogans around ‘climate smart’ agriculture in Cambodia (Nang, Citation2013). Outside of central government, the government’s land and agricultural policies are vociferously disputed. Critics charge that government policies and representatives are largely insensitive to the particularities of smallholder farming in a changing climate. As CCCN (Citation2014) asserted:

The shift toward commercial farming, requiring intensive inputs but more vulnerable to climate and market fluctuation is very pronounced in rice producing areas and is not being accompanied by measures and policies aimed at supporting smallholders and favoring a fairer distribution of wealth … Not surprisingly inequalities are increasing. (p. xiii)

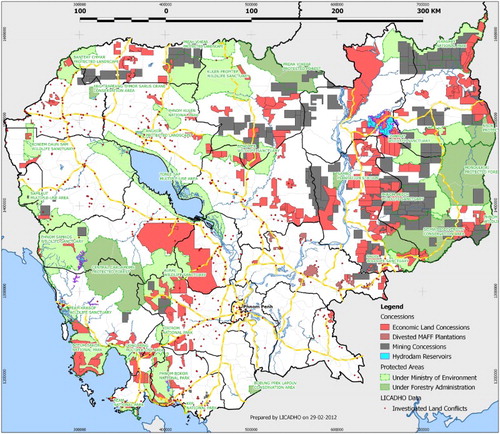

Figure 1: Map showing land concessions in Cambodia. As much as 22% of Cambodia’s land has been sold for economic concessions or other development projects in recent years (LICADHO & The Cambodia Daily, Citation2012)

In terms of human rights, Cambodian law largely meets international standards on paper, but falls considerably short in practice. The US State Department’s most recent (Citation2014) human rights report for Cambodia, for example, documents widespread transgressions and official impunity. Meanwhile, land conflicts and widespread dispossession of both rural and urban Cambodians for ELCs have emerged as explosive political issues, and the processes behind the granting of these concessions are widely regarded as contravening both Cambodian law and international standards (McGinn, Citation2013).

Is civil society connecting the dots?

There is a growing body of literature on civil society in Cambodia, including research focusing on its role in service provision, advocacy/political mobilisation, democratisation, land rights, and natural resource conflicts (see, for example Baaz and Lilja, Citation2014; Frewer, Citation2013; McGinn, Citation2013; Milne and Mahanty, Citation2015; Norman, Citation2014; Rodan and Hughes, Citation2012; Rose-Jensen, Citationin press). Frewer (Citation2013) comments on the ‘unbridled optimism’ (p. 99) of the international development community regarding NGOs in Cambodia, despite the fact that Toquevillian assumptions about its role are unsupported by evidence. Indeed, he demonstrates that they are firmly dependent on both neo-liberal development funding flows and a neo-patrimonial state bureaucracy. As such, he asserts that ‘NGOs in Cambodia play a crucial role in constructing consent’ insofar as they ‘play supportive and mediating roles’ (p. 103) between state and international development partners, both of which they are too dependent on to meaningfully challenge. The politics of CC is a new topic, with critical literature only beginning to emerge (e.g. Käkönen et al., Citation2014; Mahanty et al., Citation2015; Work, Citation2015). In terms of NGO programming, there has been a proliferation of new CCA-related initiatives in Cambodia, funded by international agencies and sometimes linked to government-led major infrastructure investments. Against this backdrop, NGOs are supported to implement community-based CCA projects, usually paired with ‘capacity building.’ It is unsurprising that there is considerable confusion as to what does and does not count as adaptation, much less how it might challenge or strengthen dominant development paradigms. Despite a nascent but growing awareness of the linkages between human rights and CC concerns, in Cambodia there are notably few efforts that explicitly ‘connect these dots’ in operations or strategic plans. Norman (Citation2014) discusses at length the twin and often conflicting roles of NGOs in Cambodia as professional service-delivery agents as well as democratic watchdogs; the pressures of the first often crowd out – if not co-opt – the latter. Rodan and Hughes (Citation2012) argue that civil society’s

social accountability mechanisms … help preserve existing power hierarchies and limit the scope for critical evaluation of prevailing reform agendas … [and] often privilege nonconfrontational state-society partnerships, drawing activists into technical and administrative processes limiting political reform possibilities by marginalizing or replacing independent collective political action crucial to the democratic political authority of citizens. (p. 367)

In Cambodia, concerns about climate justice (i.e. measures which seek to rectify the ‘inverse relationship between climate risk and responsibility’ [Barrett Citation2014: 130]) are seen by some to indicate the need for action in countries with large-scale emissions. Moreover, several interviewees indicated that there is a tendency to label more immediate problems (e.g. the impact of dams or deforestation) as being instead due to CC in order to shift the blame to developed countries and exonerate those actors within Cambodia who are responsible for environmental destruction. In this sense, the language of CCA has been co-opted to serve elite interests. One senior government official even indicated that unless donor countries were prepared to ‘step up to the plate’ and pay more than the (short-term) profits that can be reaped from exploitation of the forests, there is no reason for Cambodia to slow the current pace of destruction. ‘We look at mitigation from the perspective of an LDC, which is that we implement mitigation as long it supports sustainable development and the rich countries fund it,’ he explained. ‘Why would countries like us [protect forests]? We need development. Under the current market model there is no other way.’

There is a clear recognition that widespread deforestation is both contributing to CC and reducing the adaptive capacities of the populations living in the (often formerly) forested areas.Footnote4 Nonetheless, there is also considerable ambivalence about how this recognition should influence courses of action. This may reflect, in part, the government’s persistent downplaying of the scale and effect of deforestation in Cambodia (Milne and Mahanty, Citation2015), and NGO reluctance to risk government partnerships by openly challenging that. While cross-cutting issues are recognised, action largely remains firmly boundaried within agencies’ long-standing modi operandi. Both advocacy and operational strategies are corralled into ‘silos’ – and this is true for human rights as well as development agencies. Organisational inertia is compounded by resignation and fear about political repercussions of challenging elite interests.

While some human rights organisations address access to essential livelihood resources, most focus (usually exclusively) on legal rights and the judicial sector. As such they actively contest the legality of the ELCs and other ‘land grabs,’ but rarely address a population’s rights to protection from climate risks per se. These agencies clearly focus on the formal accountability of duty bearers to follow the law. There is some understanding of how, in principle, these accountabilities extend to issues related to CC, but this is not regarded as part of their mandate. The reduction in vulnerability to CC that results from the protection of farmland and forests is seen as a positive externality rather than as a justification for these efforts. There is also some criticism that human rights in Cambodia is dominated by a set of concerns defined by urban elite lawyers, and that the human rights agencies fail to adopt a broad approach to empowerment of the marginalised.

The four principles of HRBAs

Cambodia is undergoing rapid social, economic, political, and environmental change. Milne and Mahanty (Citation2015) assert that

the social and environmental dimensions of change are dynamic, inter-linked, multi-scalar and power laden. The major actors in this drama – government officials, conservation organizations, villagers, local NGOs, armed forces, elites and private interests – are caught in an interplay which, at a fundamental level, involves struggles over resources such as land, forests, fisheries and floodplains. (pp. 1–2)

The following analysis focuses primarily on four specific principles of HRBAs (UN, Citation2011): meaningful participation and opportunity, transparency, accountability of duty bearers, and non-discrimination. We recognise that HRBA perspectives and its principles are contested, and some argue that protecting human rights is a top-down, global, donor-driven agenda to empower the poor. However, an HRBA has been adopted by actors from the global to the grass-roots levels precisely to promote an alternative discourse and perspective to address these failures. Moreover, the UN and many other internationally agencies have formally adopted HRBA policies, in part in response to criticisms from civil society actors in developing countries. It is well worth ‘unpacking’ this concept and systematically exploring its implications for CCA in Cambodia.

Participation and opportunity

The Cambodian Government’s CC policies are grounded in a ‘trickle down’ logic which posits that economic growth inevitably leads to greater employment opportunities, which will facilitate an exit from undesirable subsistence and smallholder agriculture. This is also seen as consistent with the aspirations of the younger generation who are assumed to prefer urban and/or ‘modern’ livelihoods.Footnote5 Some in the NGO community dispute these policy assumptions; however, others emphasise their commitment to align efforts with government policies and planning.

With regard to the meaningful participation of rights holders, the INGOs and national NGOs indicate that grass-roots actors – including CBOs and constituency groups – were until very recently excluded from genuine influence on both government and NGO programming. Several interviewees explained how CBOs in Cambodia are suddenly finding their voice. This may reflect subtle changes in political space in Cambodia but also, very importantly, the increasingly precarious state of rural livelihoods in a context of widespread dispossession and deteriorating farming and fishing conditions. As a result, ‘farmers, fishers and forest-dependent villagers have become increasingly vocal and determined in Cambodia; now representing a major force for social change that the ruling party cannot ignore’ (Milne and Mahanty, Citation2015, p. 9). This, together with more recent pressures on NGOs, and perhaps the growing awareness of international norms have meant that emergent CBOs are now largely acknowledged by NGOs and donors as key to participation in advocacy efforts to demand accountability from those responsible for environmental destruction and loss of livelihoods. CBOs and resource-user associations (especially in fisheries) are also seen as having a central role in setting locally adapted ground rules and demanding effective enforcement of existing regulations.

The belated introduction of this seemingly self-evident aspect of a rights-based approach is attributed to several factors. The most important is the role of international donors in funding civil society in Cambodia, and their preference for a select group of NGOs which are able to prepare professional proposals and reports. A second issue has been patronising attitudes among educated Cambodians, including both government and NGO staff. The rural poor have been seen as ignorant, incapable, and in need of ‘champions’ to speak on their behalf. These attitudes continue to be prevalent in some quarters, particularly regarding ethnic minorities.

Transparency

The principle of transparency is perhaps most apparent in relation to increasing the visibility of the processes that are simultaneously dispossessing farmers and destroying Cambodia’s forests, that is, official land concessions coupled with rampant logging. Both of these issues are compounding rural Cambodians’ vulnerability to CC. Transparency is an important aspect of both hard advocacy (influencing public and international opinions to put pressure on government) and soft advocacy (gently persuading duty bearers through increasing their understanding of the implications of prevailing processes). Many note, however, that transparency may be created within specific contexts for raising attention to a particular rights violation, but this has little bearing on widespread impunity of those with political and/or economic power. Rodan and Hughes (Citation2012), for example, demonstrate that anticorruption agendas have been marginalised from reform efforts in Cambodia to achieve greater accountability.

Non-discrimination

With very few exceptions, discrimination receives strikingly little attention. Cambodia is unusually homogenous in terms of ethnicity – some 90 per cent of the population is Khmer, although some argue that minorities are undercounted. Nonetheless, the country also has an egregious history of gross ethnic human rights violations. Discrimination is widespread – particularly against ethnic Vietnamese who are openly vilified. There is little acknowledgement of this as a social problem, and ‘race-baiting’ is a common tactic in political campaigns – perhaps particularly by the political opposition. Even among some NGOs interviewed, Vietnamese speakers are not seen to be rights holders because they are not citizens (which is not always true). The criteria for membership in officially recognised Community Fisheries, for example, includes Cambodian citizenship (Vuthy et al., Citation2009), which effectively excludes many families of Vietnamese origin. Indigenous peoples may be particularly affected by the ELCs. There is a recognition that defence of human rights in relation to the ELCs, therefore, coincides with addressing ethnic discrimination, but this is seldom explicit.

Insensitivity about discrimination is rather surprising among organisations that would be expected to be more aware of international norms. In interviews, the differing gendered dimensions of economic development of adaptive capacities were acknowledged by some, but given notably limited attention.

Accountability

Accountability has a number of dimensions at national and local levels, and in the relations between citizens and the state. It also relates to how the state perceives its accountability for creating an enabling environment for the private sector in relation to accountability towards rights holders more generally. As noted above, Cambodian government representatives who were interviewed primarily saw themselves to be accountable for providing economic opportunities through growth and thereby the creation of formal employment. Therefore, the government sees its accountability to the interests of the economic elite as sufficient for addressing the rights of the population in general. Those aspects of CCA and mitigation which are consistent with the interests of the elite are embraced, whereas others are ignored. For example, supporting ‘modernisation’ in agro-industrial systems is seen as reducing poor people’s dependence on variable and uncertain agro-ecological conditions in smallholder farming, and therefore implies that duty bearers are indirectly accountable to vulnerable rights holders via state support to the elite.

Although NGO interviewees were largely sceptical regarding the benefits of agricultural modernisation in reducing vulnerability, few of those engaged in CCA programming were prepared to explicitly demand state accountability for the reduction of climate risk and vulnerability. NGO staff widely acknowledged that community forestry efforts, for example, are failing because they are powerless in the face of land grabs or illegal logging. Still, they remain cautious about demanding accountability among duty bearers for upholding the law, or more broadly to ensure that the claimed adaptation benefits reach the most climate vulnerable.

Duty bearers and decentralisation

A significant factor which weakens the accountability of Cambodian duty bearers is the incomplete decentralisation of power to local government, compounded by poor capacity, and generally weak implementation of stated policies. The principle of subsidiarity to local government is commonly assumed to be important for accountable and effective climate governance (UNDP, UNCDF and UNEP, Citation2010), but our interviews suggest that the ‘devil is in the details.’ Milne and Mahanty (Citation2015) have asserted that ‘the most profound challenge for Cambodia’s conservation movement … is a dissonance or disconnect between what government counterparts say they will do, and what they actually do’ (p. 14). Virtually all respondents echoed this concern: Cambodia has what one expatriate NGO manager described as ‘beautiful policies,’ but little local-level capacity or motivation to implement them.

Probably the most glaring environmental policy implementation gap is in law enforcement. Local government is universally seen as powerless to enforce laws which safeguard either the environment or environmental defenders when powerful actors are the culprit. Four factors emerged from our interviews which stymie efforts to hold local duty bearers to account for protecting the environment and respecting the rights of resource users.

Decisions about land are made in Phnom Penh. Local officials are powerless in regard to land acquisitions, and fear retribution if they act to protect their constituencies from the effects of concessions granted at central levels. The granting of a land concession tacitly goes hand in hand with a certain level of impunity regarding effects on either the local population or natural environment. NGOs indicate that local government has no power or authority regarding these issues, which makes holding it to account a futile exercise.

Local government has extremely little capacity to provide essential services. Agricultural extension agencies are often expected to act as major actors in moving climate policies into practice, an assumption that can be questioned (Christoplos, Citation2012). Cambodia’s publicly financed agricultural extension services are severely under-resourced (Nang, Citation2013) and sometimes find themselves overwhelmed by NGO expectations regarding ‘collaboration’ in climate projects (Dahlgren et al., Citation2013). To some extent, NGOs bypass duty bearers to provide extension services directly, but these are reliant on donor resources and limited to time-bound projects. Indeed, NGOs may accept this state of affairs rather passively as it provides a raison d’être for their continued service-provision niche. Some interviewees did recognise the importance of more coherent extension systems, and donors are acting accordingly, but levels of national ownership and readiness to shoulder a role as duty bearers are uncertain.

Superficial understanding and approach to CCA. When funds are made available to either the national or local government for CC mitigation and adaptation, interviewees noted a strong tendency to use these funds for projects with marginal relevance to CCA – for example, to conflate infrastructure work with ‘climate proofing.’ These are highly visible, tangible investments that can be quickly implemented and yield political benefits. However, the impacts of these investments on the environment or adaptive capacities of vulnerable populations are usually poorly assessed. The potential for maladaptation is rarely considered and there are reports of new roads increasing or shifting flooding risks due to blocked run-off.

Decentralisation processes are not being complemented by outreach to and empowerment of rights bearers at the local level. Support extended to build the capacity of local government does not include empowering local citizens. As one Cambodian interviewee argued,

their process is more about empowering the government and authorities than the people … How come we work with a commune chief who logs and threatens? They say [rights-based approach] but they are not empowering people, they are empowering a government which violates rights.

NGO categories, strategies, and limitations

The concept of ‘civil society’ encompasses diverse bodies and contested meanings; it is both broad-ranging and ambiguous. Zartman (1995, as cited by PCSG, Citation2001) has described it as

the social, economic, and political groupings that structure the demographic tissue; distinct and independent of the state but potentially under state control, performing demand and support functions in order to influence, legitimise, and/or even replace some of the activities of the state. (pp. 13–14)

Given the political economy in Cambodia, it would be expected that agencies which apply HRBAs in relation to CCA would be led into a controversial territory concerning market dynamics, power, ideology, and politics of the environment. This would lead to clashes around the inter-related issues of poor natural resource management, ineffective law enforcement (i.e. against illegal logging, fishing, and other harmful commercial practices), and widespread shady ELCs. In practice, NGOs have adopted a range of strategies to engage, manage, or sometimes even avoid these issues. It is evident that by and large NGOs are risk averse and are aware that they are confronted with a very delicate balance. As Frewer (Citation2013) has commented, ‘very few NGOs are able to successfully navigate the near impossible constraints of working partnership with an authoritarian government while simultaneously having the space to criticise and challenge state actors’ (p. 103). Moreover, they are highly dependent on official development assistance (ODA) from abroad; their growth has been driven by the availability of funding; and they have been characterised as ‘a civil society movement without citizens’ (Un, 2004, cited by Khieng and Dahles, Citation2015, p. 1416). Many therefore choose to focus on technical projects which can be implemented without confrontation with duty bearers.

Nevertheless, many NGO workers and managers express deep commitment and are doing their best to navigate very real constraints of dependence on ODA and working relationships with authorities. It is easy to be dismissive of NGOs as artificial, reflecting academic research on the topic conducted a few years ago. The context is changing rapidly and there is now foment at the grass roots, including rural areas, and especially among youths. The political opposition is increasingly viable, and emerging CBOs are taking ‘rabble-rouser’ positions – often bypassing more established NGOs (see, for example, Parnell, Citation2015; Rose-Jensen, Citationin press). In the political realm, Baaz and Lilja (Citation2014) highlight that ‘Cambodians … realize that there is more to democracy than voter registration’ (p. 6), although they argue that the nation’s ‘hybrid democracy’ continues to be characterised by patronage systems wherein people ally themselves with powerful individuals, rather than ideas. Nevertheless, there is also evidence that some NGO workers and village ‘participants’ are embracing the language of HRBAs as a discourse of resistance to development of ‘business-as-usual’ in Cambodia. There are echoes of the example of King Sihanouk: in 1941, this seemingly pliable young man was hand-picked to facilitate colonial rule; instead, he defied the French and led the country to independence.

Some would argue that an HRBA perspective would necessitate a confrontational stance on the land and natural resource conflicts in Cambodia, insofar as they undermine the adaptive capacities of rights holders. This would lead directly to demands on the state regarding transparency, accountability, conflicts of interest, and impunity. It could even be claimed that HRBAs would demand efforts to ‘name and shame’ those who are not respecting the rights of populations whose climate vulnerability is being increased due to the plunder of Cambodia’s environment. This involves considerable risks. The INGO Global Witness published a scathing (Citation2007) document on deforestation in Cambodia, charging that illegal logging was associated with the families of top government officials. The agency was banned from further operations in the country.

Many NGO staff in Cambodia are of the view that confrontations are ineffective and even dangerous. Bold action may endanger vulnerable populations and place both activist leaders and communities at risk of violence or more subtle retribution. Indeed, in May 2016, five human rights and independent election workers were arrested in Cambodia and declared Prisoners of Conscience by Amnesty International (Meyn, Citation2016). The alternative perspective encourages ‘soft advocacy’ strategies to engage in dialogue on how resources can be managed in a more equitable and ‘climate smart’ manner. Those who embrace this strategy generally acknowledge that their efforts are unlikely to be transformative. However, they assert that this is all that can be achieved under current circumstances.

Some argue that the growing strength and confidence of the affected communities – and the escalating strength of political opposition to the entrenched ruling party – has meant that local authorities are starting to recognise the dangers of ignoring their ‘downward’ accountability to constituencies. The quality of local leadership is often mentioned as a significant factor in this regard, together with how influential outside forces are in achieving more ‘upward’ accountability. It has also been noted that there has been more success in protecting fish stocks, for example, due to the fact that the exploitive agents themselves are less powerful to begin with. Nevertheless, those who openly challenge what one long-term expatriate resident described as ‘Cambodia’s tightly controlled system of patronage’ risk being blacklisted and shut out from government access altogether. As one government official stated, ‘The NGOs have to understand the reform agenda of the government. We will not provide funding to NGOs who want to bring the government down. We want to improve service delivery and build a partnership together’ (Ngy, 2009, as cited by Rodan and Hughes, Citation2012, p. 377). In some cases, there have been threats or acts of violence as well; the 2012 murder of environmental activist Chhut Vuthy has had an especially chilling effect. This contributes to self-censorship among the NGOs.

Hard, soft, and complacent advocacy

When development-oriented NGOs in Cambodia engage in independent advocacy efforts, they usually do so as partners within a coalition. There are numerous independent NGO networks. Most concern specific issues or constituencies, and there is also one major independent coordination body of which nearly all the national and international ‘professional’ development NGOs are members. In addition to general coordination functions, these networks aim to enhance the capacity of their members and present a ‘united voice’ for advocacy. This is especially critical for agencies with a technical orientation, which might not otherwise fully engage on policy and advocacy issues.

Interviewees voiced a wide range of opinions about the effectiveness of NGO networks’ advocacy efforts. Many rely on them to take stronger advocacy positions that would not be prudent for an individual agency to adopt. While many were satisfied, criticisms were also expressed. Perhaps the most important is that, in one expatriate NGO manager’s words,

too much is expected of an umbrella, and everyone hides behind it. Everything difficult goes to it, but it doesn’t have enough support. They pass the buck, and [the network] has too much on its plate and everyone vanishes … It just gets left holding the ball.

Most NGOs align themselves with either ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ advocacy, and this in turn determines their advocacy strategy; Rodan and Hughes (Citation2012) argue that the distinction between political and development NGOs is ‘useful to the government’ (p. 377). Our interviews confirmed that NGOs’ advocacy strategies are predetermined by how the agency wishes to situate itself within the political landscape, rather than the underlying analysis of what is needed to address a particular issue. Indeed, there were criticisms that agencies adopt a ‘knee-jerk’ response. Usually, this criticism was expressed regarding NGOs which actively discouraged communities or constituencies from confrontations with the state. However, some have also criticised the other end of the spectrum, charging that they unnecessarily stoke conflict and thereby recklessly endanger the people or interests they purport to represent.

It is not possible to generalise which approach is most effective; McGinn (Citation2013) observed that both were failing, and Rose-Jensen (Citationin press) has commented that the distinction between ‘real’ grass-roots agencies and the so-called astroturf ones, driven by outside interests and funding, may be unhelpful and lacking nuance. Moreover, it is arguable that in the current political climate, both hard and soft advocacy approaches have been ineffective. Many interviewees were particularly pessimistic regarding the future of Cambodia’s forests and smallholder farms. A large proportion of informants at all levels (including government and multilateral agencies) indicated that they felt unable to address the ‘real’ issues altogether, as that would compromise their government relationships. Some accepted this state of affairs and expressed satisfaction with achievements like input into draft environmental impact assessment legislation. Others sounded cynical or defeated, making comments like the lawyer who lamented, ‘land cases are hopeless.’

The post-war legacy and a state without duties

The role of international and national NGOs was forged in the post-war period, when the international community embarked on an ambitious effort to put Cambodia back together. The United Nations assumed, for the first time, direct administrative control of a collapsed state, accompanied by a massive influx of foreign aid money. After the control of the country was returned to the national government, pipeline problems in this very fragile state quickly arose and the international community responded by directing enormous levels of funding and responsibilities to NGOs. As is often the case in fragile states, the exit strategy whereby the government would reassume these responsibilities was not very explicit. Although there were international commitments to ushering in a vibrant and strong civil society, those agencies which received funds were, necessarily, those which could meet donor expectations and criteria. In this sense, civil society in Cambodia was very much birthed by the international community. The paradox, of course, was that Cambodia was home to one of the highest concentrations of NGOs in the world, but they were highly dependent and adopted a service-delivery orientation which lacked ‘basic civil society features’ (Ou and Kim, Citation2013, v).

Today the government is making significant progress in developing capacities and is taking strong steps towards reassuming its role as a duty bearer. But our findings suggest that the duties it is ready to bear are highly selective and reflect a general view that the market will respond to most needs. CC policies are being developed, but the apparent lack of ownership of these donor-driven documents has meant that the government does not assume a leading role. Among NGOs as well, CC may represent a new ‘buzzword’ to be applied to fundraising proposals; as one manager commented to Frewer (Citation2013), ‘I think we must also consider climate change’ (p. 107) in order to sustain funding. Instead, Käkönen et al. (Citation2014) demonstrate how effectively CC has been depoliticised in Cambodia by adopting ‘expert’ technologies and policy narratives, ‘rendering it more easily governable through existing bureaucratic planning processes and without challenging the current structures of political economy’ (p. 351). Work (Citation2015) further questions whether mitigation initiatives may ‘constitute land grabbing under the guise of conservation and biodiversity protection … in the extractive and power-laden climate of contemporary Cambodia’ (p. 25). It is arguable that the main underlying challenge to a concerted HRBA is that CC is too often and easily framed as a challenge of technology transfer. Guidelines and training programmes to promote various forms of ‘climate smart agriculture,’ for example, tend to downplay the social, political, and economic drivers of risk and resilience, and also omit legal frameworks regarding land and services that largely determine ‘whose adaptation counts.’ While technological strategies to improve agricultural production or access to water are welcome and valuable, CCA encompasses more than that. As Bours et al. (Citation2014a) have written,

It must also be understood that vulnerability and resilience to climate change are profoundly shaped by social structures and institutions. Adaptation strategies should reflect a nuanced analysis that captures how distinct groups within the population are affected differently … The most vulnerable groups may be uniquely or differently vulnerable from the community at large – and from each other. The poorest and most marginalised often have weakest access to resources with which to effectively cope, and their needs may be missed in general ‘community’ interventions. (p. 12)

Conclusion: towards a rights-based climate agenda

Despite organisational commitments to HRBAs, in Cambodia this perspective is only cautiously being applied to CC and in general. Given the extent to which human rights abuses are reducing vulnerable peoples’ adaptive capacities and contributing to maladaptation, in the future this linkage will be increasingly difficult to ignore. A rights-based approach could be a way to challenge the dominant paradigm which favours apolitical ‘quick fixes’ or technical ‘solutions’ over strategies grounded in a coherent analysis and theory of change for empowering climate-vulnerable populations. Indeed, HRBAs can be a counterweight to what Norman (Citation2014) refers to as the ‘dissent dampening’ (p. 257) effect of technocratic trends among Cambodia’s NGOs. If and when CC financing begins to flow in earnest, some hard choices will need to be made, and HRBAs are intended to provide important locally relevant normative and principled guidance for making such choices. Indeed, there is a growing professional concern over superficial and technocratic approaches to ‘resilience,’ and that there is a trend towards more stringent criteria regarding coherent and incisive vulnerability analyses (Bours et al., Citation2014b; Christoplos, Citation2014).

Cambodia exemplifies both the opportunities and the obstacles of applying HRBAs. Prospects for a rights-based approach to CC are actively undermined by the state’s failure to accept responsibility for maladaptive and non-inclusive development polices, and civil society is, for the most part, too dependent on maintaining its working relations with the government and funding flows from donors to act as an effective watchdog. As Frewer (Citation2013) commented, ‘the priority of an NGO [in Cambodia] is organisational existence and survival rather than creating alternatives to neoliberal development … [and this] seriously limits the possibilities for NGOs to play a significant role in social change’ (p. 108). In this context, it is perhaps naive to expect an external conceptual framework like HRBAs to bring about transformative change with a deck stacked, so to speak, against such change. It is easy to draw cynical conclusions that unpacking the application of HRBAs underscores the limitations of such frameworks to ever realise their aims. We adopt an alternative interpretation, which is to highlight what is needed to address the obstacles.

Further efforts are needed to narrow the gap between hard and soft advocacy by finding synergies between outside pressure on duty bearers and inside support for them to strengthen their capacities to shoulder their responsibilities. Moreover, advocacy strategies should be grounded in more coherent analyses of effecting change, rather than simply following predetermined formulae. This perspective also implies that NGOs should develop and articulate more coherent theories of change, and more attention to the ‘big picture’ and the factors that can contribute to capacities of climate-vulnerable people to protect themselves from extreme events. This would involve perspectives that transcend narrow technical roles and interventions. Furthermore, those adopting a rights perspective cannot turn a blind eye to the lack of policy implementation. International and national climate efforts on policy development need to be better balanced with thornier questions of implementation and accountability. In Cambodia, this suggests a need to develop capacities to challenge impunity, pervasive conflicts of interests, and the lack of law enforcement. Weak rule of law is in many respects the most pressing CC issue, and an HRBA can draw attention to what is needed after laws are passed.

A link between CC and HRBAs thus requires anchoring advocacy within broader governance efforts that promote the participation of vulnerable populations in national development, pressure for greater transparency, accountability of duty bearers, and spotlighting discriminatory governance practices. If this framework is applied, it could contribute to breaking down the ‘silos’ that treat climate risk as a technical or sectoral concern rather than as an impetus for political and institutional change. It also implies that human rights organisations should expand their vision beyond legal perspectives and consider the implications of trends in control of resources that will determine adaptive capacity, including broader issues of participation, mobilisation, and empowerment.

Acknowledgements

We are very appreciative of the thoughtful comments and feedback from Dr Mikkel Funder, Dr Richard McGinn, Dr Winnie Wairimu and the two anonymous reviewers.

Notes on contributors

Dr Ian Christoplos is senior researcher at the Danish Institute for International Studies. He also works as a professional evaluator, as part of which he actively strives to apply a human rights perspective. His research, consultancy and evaluations cover a broad range of issues, with a major focus on disaster/climate risk, conflict, rural development and agricultural services. His research and other assignments have included programmes in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Western Balkans. He is currently leading a Danish financed research programme on climate change and rural institutions.

Dr Colleen McGinn is an independent research consultant. She is an expert in population coping, adaptation, and resilience and has a long track record in applied research, M&E and programme management across Asia, Africa and the Balkans. Colleen holds a PhD from the Columbia University School of Social Work, an MA in Development Studies from Tulane University and a BA in Political Science from Ohio University. Email: [email protected]; [email protected]

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1In Cambodia the term ‘NGO’ refers to ‘private, non-profit, professional organizations with a distinctive legal character, concerned with public welfare goals’ (Clarke 1998, as cited by Ou and Kim, Citation2013, p. 2). Community-based organisations (CBOs), by contrast, may be much more informal. Often conflated with ‘grass-roots organisations,’ CBOs have been defined as ‘voluntary associations of community members that reflect the interests of a broader constituency’ (Kaplan, Msoki, and Soal, 1994, as cited by Lentfer and Yachkaschi, Citation2009, p. 2). They often consist entirely of volunteers and activists, tend to be located in villages rather than cities, and may not be registered with or recognised by the state.

2Climate change adaptation refers to how individuals, communities, and countries manage the adverse effects of climate change so that people are more resilient. Mitigation policies and programmes, by contrast, seek to reduce the rate or extent of CC itself, usually through controlling greenhouse gas emissions and preserving forests and other carbon sinks.

3Although the issuing of new ELCs was suspended in 2012, land tenure security remains a highly controversial and contested topic in Cambodia. A full discussion is outside the scope of this paper, and we recommend those who are seeking a detailed review to consult Work (Citation2015).

4Readers may also wish to consult the research being conducted by the MOSAIC project (www.iss.nl/mosaic) which explores the intersections between CC mitigation strategies and elite land capture in Cambodia and Myanmar. Work’s (Citation2015) research particularly highlights the issuing of ELCs to clear forest land for ‘green’ biofuel crops, and failing forest conservation strategies which have had negative effects on both the environment and resident populations.

5NGO programmes focused on smallholders are acknowledged even by some NGO staff as being out of touch with these aspirations. As one expatriate manager commented, ‘people don’t want to be subsistence farmers anymore, and nobody wants that for their kids, but NGOs are still often stuck in a yeoman farmer fallacy.’ Others, however, articulate how villagers despair the prospect of losing their farms, and/or sending young relatives to factories, cities, or abroad in search of wage labour under difficult and often dangerous circumstances.

References

- Baaz, M. and M. Lilja, 2014, ‘Understanding hybrid democracy in Cambodia: The nexus between liberal democracy, the state, civil society, and a “politics of presence”’, Asian Politics and Policy, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 5–24. doi: 10.1111/aspp.12086

- Barrett, S., 2014, ‘Subnational climate justice? Adaptation finance distribution and climate vulnerability’, World Development, Vol. 58, pp. 130–142. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.014

- Bours, D., C. McGinn and P. Pringle, 2014a, ‘Agriculture and food security in a changing climate – Lessons learned from Asian programme evaluations’, http://www.ukcip.org.uk/wordpress/wp-content/PDFs/UKCIP-SeaChange-MandE-ER1-agriculture.pdf (accessed 16 February 2015).

- Bours, D., C. McGinn and P. Pringle, 2014b, ‘Evaluation review 2: International and donor agency portfolio evaluations: Trends in monitoring and evaluation of climate change adaptation programmes’, http://www.ukcip.org.uk/wordpress/wp-content/PDFs/UKCIP-SeaChange-MandE-ER2-donor-agencies.pdf (accessed 16 February 2015).

- CCCN (Cambodia Climate Change Network), 2014, Many Factors in an Uncertain Future: Situation Climate Change Among Local Community Priority in CAMBODIA, Phnom Penh: Author.

- Christoplos, I., 2012, ‘Climate advice and extension practice’, Danish Journal of Geography, Vol. 112, No. 2, pp. 183–193. doi: 10.1080/00167223.2012.741882

- Christoplos, I., 2014, ‘Resilience, rights and results in Swedish development cooperation’, Resilience: International Policies, Practices and Discourses, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 88–99. doi: 10.1080/21693293.2014.914767

- Climate Change Department, 2014, ‘ Cambodia climate change alliance – Description’, http://www.camclimate.org.kh/en/activities/cambodian-climate-change-alliance/21-activities/ccca/ccca-core/46-ccca-background-and-approach.html (accessed 18 November 2014).

- Dahlgren, S., I. Christoplos and C. Phanith, 2013, Evaluation of the joint climate change initiative (JCCI) in Cambodia, Stockholm: Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA), http://www.sida.se/contentassets/987bfff9965c405c99391d49618c2b68/evaluation-of-the-joint-climate-change-initiative-jcci-in-cambodia—final-report_3706.pdf.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization), 2014, Cambodia FAOStat, http://faostat.fao.org/CountryProfiles/Country_Profile/Direct.aspx?lang=en&area=115 (accessed 18 November 2014).

- Frewer, T., 2013, ‘Doing NGO work: The politics of being civil society and promoting good governance in Cambodia’, Australian Geographer, Vol. 44, No. 1, pp. 97–114. doi: 10.1080/00049182.2013.765350

- Global Witness, 2007, Cambodia’s Family Trees: Illegal Logging and the Stripping of Public Assets by Cambodia’s Elite, London: Author.

- Heng, C.T. and R. Pech, 2009, ‘Vulnerability and adaptation assessment to climate change in agriculture sector in Cambodia’, [Power Point] Presentation for Workshop on building climate resilience in the agriculture sector of Asia and the Pacific, Manila: Asian Development Bank, http://www.icrisat.org/what-we-do/impi/meetings-cc/14_15May2009/HC%20Thoeun%20Present%20on%20CC%20and%20Agriculture%20in%20Cambodia-14-15%20May%202009.pdf (accessed 16 February 2015).

- Ironside, J., 2015, What about the ‘unprotected’ areas? Building on traditional forms of ownership and land use for dealing with new contexts, in S. Milne and S. Mahanty, eds, Conservation and Development in Cambodia: Exploring Frontiers in Nature, State and Society, London: Routledge, pp. 203–224.

- Käkönen, M., L. Lebel, K. Karhunmaa, V. Dany and T. Thuon, 2014, ‘Rendering climate change governable in the least-developed countries: Policy narratives and expert technologies in Cambodia’, Forum for Development Studies, Vol. 41, No. 3, pp. 351–376. doi: 10.1080/08039410.2014.962599

- Khieng, S. and H. Dahles, 2015, ‘Resource dependence and effects of funding diversification strategies among NGOs in Cambodia’, VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, Vol. 26, pp. 1412–1437. doi: 10.1007/s11266-014-9485-7

- Kraemer, M. and L. Negrila, 2014, Climate Change Is a Global Mega-trend for Sovereign Risk, New York: McGraw Hill Financial, http://www.acclimatise.uk.com/login/uploaded/resources/climate-change-is-a-global-mega-trend-for-sovereign-risk-15-may-14-.pdf (accessed 16 February 2015).

- Lentfer, J. and S. Yachkaschi, 2009, ‘ The glass is half full? Understanding organizational development within community-based organizations’, http://hiidunia.com/The%20glass%20half%20full%20Understanding%20organizational%20development%20within%20community%20based%20organizations%20pdf.pdf (accessed 16 February 2015).

- LICADHO (Cambodian League for the Defense and Promotion of Human Rights) and The Cambodia Daily, 2012, ‘Carving up Cambodia one concession at a time’, http://www.licadho-cambodia.org/land2012 (accessed 17 September 2015).

- Mahanty, S., A. Bradley and S. Milne, 2015, The forest carbon commodity chain in Cambodia’s voluntary carbon market, in S. Milne and S. Mahanty, eds, Conservation and Development in Cambodia: Exploring Frontiers in Nature, State and Society, London: Routledge, pp. 258–279.

- McGinn, C., 2013, ‘ Every day is difficult for my body and my heart’, Forced evictions in Phnom Penh, Cambodia: Women’s narratives of risk and resilience, PhD Dissertation, Columbia University.

- Meyn, C., 2016, ‘Amnesty mobilizes for adhoc five’, The Cambodia Daily, https://www.cambodiadaily.com/second2/amnesty-mobilizes-for-adhoc-five-112985/ (accessed 28 May 2016).

- Milne, S. and S. Mahanty, 2015, The political ecology of Cambodia’s transformation, in S. Milne and S. Mahanty, eds, Conservation and Development in Cambodia: Exploring Frontiers in Nature, State and Society, London: Routledge, pp. 1–27.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, 2014, Climate Change Priorities Action Plan for agriculture, forestry and fisheries sector 2014–2018, Phnom Penh: Author.

- Ministry of Health, 2014, National Climate Change Action Plan for Public Health 2014–2018, Phnom Penh: Author.

- Nang, P., 2013, Climate Change Adaptation and Livelihoods in Inclusive Growth: A Review of Climate Change Impacts and Adaptive Capacity in Cambodia, Phnom Penh: Cambodia Development Resource Institute (CDRI), http://www.cdri.org.kh/webdata/download/wp/wp82e.pdf (accessed 16 February 2015).

- Norman, D.J., 2014, ‘From shouting to counting: Civil society and good governance reform in Cambodia’, The Pacific Review, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 241–264. doi: 10.1080/09512748.2014.882393

- Ou, S. and S. Kim, 2013, 20 Years’ Strengthening of Cambodian Civil Society: Time for Reflection, Phnom Penh: Cambodia Development Resource Institute (CDRI), http://www.cdri.org.kh/webdata/download/wp/wp85e.pdf (accessed 16 February 2015).

- Parnell, T., 2015, Story-telling and social change: A case study of the Prey Lang Community Network, in S. Milne and S. Mahanty, eds, Conservation and Development in Cambodia: Exploring Frontiers in Nature, State and Society, London: Routledge, pp. 258–279.

- PCSG (Payson Conflict Study Group), 2001, A Glossary on Violent Conflict: Terms and Concepts Used in Conflict Prevention, Mitigation, and Resolution in the Context of Disaster Relief and Sustainable Development, New Orleans: Payson Center for International Development and Technology Transfer, Tulane University, http://reliefweb.int/report/world/glossary-violent-conflict-terms-and-concepts-used-conflict-prevention-mitigation-and (accessed 16 February 2015).

- PreventionWeb., n.d., Flood – Hazard Profile, http://www.preventionweb.net/english/hazards/statistics/risk.php?hid=62 (accessed 17 November 2014)

- Rodan, G. and C. Hughes, 2012, ‘Ideological coalitions and the international promotion of social accountability: The Philippines and Cambodia compared’, International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 56, pp. 367–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2011.00709.x

- Rose-Jensen, S., in press, ‘Everything we do is democracy: Women and youth in land rights social mobilization in Cambodia’, Journal of Mason Graduate Research, Vol. 3, No. 3.

- Sherchan, D., 2015, Cambodia: The Bitter Taste of Sugar Displacement and Dispossession in Oddar Meanchey Province, Phnom Penh: ActionAid Cambodia and Oxfam GB.

- Sobal, J., 2001, ‘Sample extensiveness in qualitative nutrition education research’, Journal of Nutrition Education, Vol. 33, No. 4, pp. 184–192. doi: 10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60030-4

- Spearman, M. and H. McGray, 2011, Making Adaptation Count: Concepts and Options for Monitoring and Evaluation of Climate Change Adaptation, Bonn: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung (BMZ), and World Resources Institute (WRI), http://www.seachangecop.org/node/107 (accessed 16 February 2015).

- State Department, 2014, Cambodia 2014 Human Rights Report, Washington, DC: United States Government, http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/humanrightsreport/index.htm#wrapper (accessed 14 September 2015).

- UN (United Nations General Assembly), 2011, The right to Development: Report of the Secretary-General, New York: Author, http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N11/439/53/PDF/N1143953.pdf?OpenElement (accessed 17 November 2014).

- UNDP, UNCDF and UNEP, 2010, Local Governance and climate change: A discussion note, December 2010, Bangkok.

- Vuthy, L., R. Rivera-Guleb, J. Tsatsaros, T. Phearak and A. Cheam Pe, 2009, Understanding self-help groups for credit in community fisheries in Cambodia, in P. Beaupre, J. Taylor, T. Carson, K. Han, H. Chinda, N. Baromey, K. Han, H. Chinda, M. Monyrak, S. Sokngy and K. Piseth, eds, Emerging Trends, Challenges and Innovations: Community Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) in Cambodia, Phnom Penh: CBNRM Learning Institute, pp. 416–36.

- Work, C., 2015, Intersections of Climate Change Mitigation Policies, Land Grabbing and Conflict in a Fragile State: Insights from Cambodia, MOSAIC Working Paper Series No. 2, Rotterdam: International Institute of Social Studies.

- World Bank, 2014, World Development Indicators, Washington, DC: Author, http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators (accessed 18 November 2014).