Abstract

Global food security governance is fraught with fragmentation, overlap and complexity. While calls for coordination and coherence abound, establishing an inter-organizational order at this level seems to remain difficult. While the emphasis in the literature has so far been on the global level, we know less about dynamics of inter-organizational relations in food security governance at the country level, and empirical studies are lacking. It is this research gap the article seeks to address by posing the following research question: In how far does inter-organizational order develop in the organizational field of food security governance at the country level? Theoretically and conceptually, the article draws on sociological institutionalism, and on work on inter-organizational relations. Empirically, the article conducts an exploratory case study of the organizational field of food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire, building on a qualitative content analysis of organizational documents covering a period from 2003 to 2016 and semi-structured interviews with staff of international organizations from 2016. The article demonstrates that not all of the developments attributed to food security governance at the global level play out in the same way at the country level. Rather, in the case of Côte d’Ivoire there are signs for a certain degree of coherence between IOs in the field of food security governance and even for an – albeit limited – division of labour. However, this only holds for specific dimensions of the inter-organizational order and appears to be subject to continuous contestation and reinterpretation under the surface.

IntroductionFootnote1

Global food security governance, as many other issue areas in global governance today, seems to be fraught with a whole range of problems. First, the global governance of food and hunger is ‘highly fragmented in practice’ and ‘characterized by a poor coordination of tasks’ (Clapp, Citation2014, p. 645). Second, fragmentation of global political authority, a ‘most harmful and outrageous deficiency of the current food security governance regime’ (McKeon, Citation2015, p. 103), abounds, as economic power in global food security governance has been more and more concentrated within a limited number of multinational enterprises. Third, overlap is identified as a pervasive and arguably detrimental feature: regarding international organizations’ (IOs) mandates (Clapp and Cohen, Citation2010), regarding operational activities and instruments (Gaus and Steets, Citation2012) and regarding rules and policies (McKeon, Citation2015). On top, complexity prevails, as ‘food security is a highly complex and multi-dimensional issue that is impacted by a broad range of drivers and food system activities, stretches across various scales, and involves multiple sectors and policy domains’ (Candel, Citation2014, 591f). The literature on food security governance accordingly observes a wide range of problems. However, there are two relevant caveats: On the one hand, as Candel criticizes, empirical foundations are lacking and ‘a large proportion of the current literature focuses on what food security governance should ideally look like, instead of how the governance system is functioning at present’ (Citation2014, p. 598). On the other, as Margulis points out, ‘there remains a deficit in the literature about the global governance of food security, and in particular with respect to inter-organizational relations’ (Citation2017, p. 520).

Against this background, I seek to address these research gaps by a) providing an empirically informed investigation of food security governance rather than a normative piece, and b) focusing on inter-organizational relations in this field. Therein, I make two further shifts in c) ‘going down’ to the country level rather than looking at the global level, and d) placing emphasis on convergence between IOs and the possible development of types of inter-organizational order, rather than further divergence.Footnote2 Accordingly, my research question is: In how far does inter-organizational order develop in the organizational field of food security governance at the country level?

Theoretically and conceptually, the article draws on sociological institutionalism, and on work on inter-organizational relations. Empirically, I present and discuss findings from an exploratory case study of the organizational field of food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire, therein ‘going down’ from the global level and focusing on the case of a specific country. To do so, I build on the results of a qualitative content analysis of organizational documents covering a period from 2003 to 2016 and semi-structured interviews with IO staff conducted in 2016. Accordingly, the objectives of the article are to develop a view from the field, to demonstrate which types of inter-organizational relations IOs engage in, and to tease out in how far inter-organizational order evolves or is created within the field of food security governance at a country level. Analysing inter-organizational relations is important for understanding food security governance for at least two reasons: First, food security governance is increasingly understood by applying concepts such as regime complexes (e.g. Margulis, Citation2013), which highlight the multiple mutual linkages between different IOs active in different areas of food security governance. If these IOs influence each other in their work and the activities of one IO have implications for those of another, than it matters how IOs seek to address these issues through their inter-organizational relations, e.g. by establishing an inter-organizational order. Second, enhanced coordination and the establishment of some form of a division of labour are oftentimes believed to lead to improvements in the provision of food security; accordingly, inter-organizational relations may also matter for questions of effectiveness in food security governance. Importantly, I demonstrate in this article that not all of the developments attributed to food security governance at the global level play out in the same way at the country level. Rather, in the case of Côte d’Ivoire there are signs for a certain degree of coherence between IOs and even for an – albeit limited – division of labour.

Theoretical and conceptual framework

Theoretically and conceptually, the article draws on sociological institutionalism (e.g. DiMaggio and Powell, Citation1983) and on work on inter-organizational relations (Biermann, Citation2011). Therein, sociological institutionalism has the distinct advantage of situating inter-organizational relations not within a void or an empty space, but locating it within and connected to a broader ‘outer-world’ structure (see also Franke and Koch, Citation2017; Holzscheiter, Citation2014b; Vetterlein and Moschella, Citation2014). While such an approach has the advantage of going beyond dyadic inter-organizational relations and instead shifting emphasis to broader environments and communities of IOs and other actors, at the same time, it widens the field of actors to a point where it potentially becomes unwieldy and too vast.

The section begins by elaborating upon the organizational field as a core concept of sociological institutionalism, before turning to work on inter-organizational relations, which provides relevant conceptual distinctions. Finally, coherence and division of labour are introduced as two types of inter-organizational order. Overall, the purpose of this section is to establish a theoretical understanding of IOs as partially independent actors embedded within an organizational field, and to introduce those concepts which later on guide the empirical analysis.

An organizational field approach

When thinking about evolving orders, it is not sufficient to focus on individual IOs. Rather, IOs are more usefully understood as part of a broader organizational setting; as actors which are embedded within a societal environment with which they interact. There are numerous and varied flows of influence, mutual linkages and inter-relations between IOs and the environment (Franke and Koch, Citation2017). Rather than being a static model, sociological institutionalism allows for dynamic and changing relationships among actors and the environment. As the notion of the environment sometimes remains rather vague and a catch-all phrase for everything outside of the individual organization, IOs are conceptualized here to be part of an organizational field to be analytically clearer. Such an approach has already been applied to global food issues. One example is Schwindenhammer’s (Citation2017) analysis of global organic agricultural policy-making through standards, where she identifies distinct phases of institutional development shaped by IOs, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and businesses.

So what is an organizational field? In the seminal definition of DiMaggio and Powell, the organizational field can be understood as ‘those organizations, that, in the aggregate, constitute a recognized area of institutional life: key suppliers, resource and product consumers, regulatory agencies, and other organizations that produce similar services or products’, thus, ‘the totality of relevant actors’ (DiMaggio and Powell, Citation1983, p. 148). While DiMaggio and Powell were referring to other types of organizations in their seminal contribution, for example hospitals, I posit that the concept of organizational fields is also applicable to IOs (see also Vetterlein and Moschella, Citation2014). This builds on an understanding of IOs as organizations: IOs are not only instruments of member states through which these assert their particular interests, or arenas for negotiations between their members, rather they are understood as partially independent actors in their own right which have a certain degree of agency (Koch, Citation2014). While DiMaggio and Powell point out different types of actors in their definition, such as ‘key suppliers’ or ‘regulatory agencies’, there are other types of actors of relevance for IOs. These are located within the organizational field, such as NGOs, donors, or civil society groups. Importantly, DiMaggio and Powell’s definition points out that there are numerous stakeholders within the organizational field, which can have an impact on the organization and vice-versa. Drawing on the concept of an organizational field then allows for conceptualizing a setting within which inter-organizational interaction among these actors takes place. While the organizational field is composed of different types of actors on the one hand, it encompasses communities of organizations who have similar functions or roles on the other. Therein, these organizations are aware of one another, engage with one another and see each other as ‘peers’ or ‘similar’ in some relevant regard (Dingwerth and Pattberg, Citation2009). Overall, the organizational field is constituted by actors that are similar to one another, i.e. other IOs, as well as by actors that are different but part of a broader organizational constituency, i.e. NGOs and donors.

The organizational field then has three defining characteristics: A concrete object pertaining to which the field establishes itself, the power relations among those organizations participating in the field and the specific norms and rules that emerge and become the ‘rules of the game’ (Vetterlein and Moschella, Citation2014, p. 149). It is only through the activities of different organizations that the organizational field emerges in the first place; then, it feeds back and influences the organizations and possible new entrants to the field (DiMaggio and Powell, Citation1983).

Analysing the three characteristics in turn allows for some further insights regarding the relations IOs engage in. The first component, i.e. the ‘object around which the field constitutes itself’ (Vetterlein and Moschella, Citation2014, p. 149), underlines the importance of organizations in the process of creating and redefining a field. An organizational field is not exogenously given; rather, actors actively (re)construct it and define an entry point which is of common interest to them and around which they converge. Linking back to the definition by DiMaggio and Powell introduced above, it is decisive that organizations ‘constitute a recognized area of institutional life’ (emphasis added, Citation1983, p. 148). Accordingly, the organizational field has a perception-based element to it and requires recognition by those involved, meaning for example that organizations are aware of each other and engage in interactions.

The second characteristic of organizational fields are the power relations among those organizations that constitute the field. Phillips et al. (Citation2000, 32f.) differentiate three types of power: formal authority, control over resources and discursive legitimacy. Formal authority therein is the ‘legitimately recognized right to make decisions’, understood as ‘the right to make decisions which are somehow crucial to the collaboration’ (ibid.). In general, inter-organizational relations are not characterized by hierarchy; however, the ‘right to make decisions which are somehow crucial to the collaboration’ is a less restrictive definition which allows to grasp inter-organizational relations which are non-hierarchical but where nonetheless the decisions of one organization have an impact for inter-organizational relations. Key is that the other members of the organizational field attribute a legitimately recognized right to one or more organizations to make such decisions. A second source of power in inter-organizational relations is the control over resources, in particular over scarce or critical resources. These can range from material (e.g. financial capital) to ideational resources (e.g. expertise). Resource dependency approaches (Pfeffer and Salancik, Citation2003) – although not explicitly linking back to the organizational field concept – theorize the role of such material and ideational resources. Furthermore, they advance propositions on how diverging resource endowments and resource requirements affect organizations and the interactions they engage in. Organizations therein can be dependent from other actors in their environment for acquiring resources. Control over resources can be an important advantage for organizations when engaging with others. How resources are distributed will also have effects on inter-organizational relations: Given a roughly similar resource endowment, one could expect organizations to interact on an equal footing and to jointly negotiate their collaborative engagement, e.g. to pool resources. If, on the other hand, one organization is dependent upon another for funding this alters the relationship and makes it more asymmetrical – unless the second organization has another resource which the first one needs. Finally, discursive legitimacy – understood as ‘the ability to speak legitimately for issues or other organizations’ (Phillips et al., Citation2000, 32f.) is also a source of power in inter-organizational relations. For example, some IOs are perceived to be – and see themselves – as ‘knowledge organizations’ with the capacity to speak authoritatively on certain issues, especially if the organization does significant research on a certain issue itself – such as the World Bank with regard to poverty (Vetterlein, Citation2012).

Finally, the organizational field is characterized by specific norms and rules that become the ‘rules of the game’. These rules proscribe certain behaviours or actions which organizations are expected to engage in if they belong to a particular organizational field. In that sense, the notion of a field is similar to that of a regime as conceptualized by Krasner (Citation1983; cf. Vetterlein and Moschella, Citation2014, p. 149). If the ‘rules of the game’ for example stipulate cooperative behaviour among organizations, it is more likely that organizations will attempt to collaborate with one another, or at least to appear to do so, as adherence to normative requirements increases legitimacy in the eyes of the environment from which these demands arise.

Inter-organizational relations

Inter-organizational relations are repeated and purposeful interactions among organizations (Holzscheiter, Citation2014a). They can involve different types of organizations (public or private/ state or non-state), refer to relations among two (dyadic) or more (multiple) actors (Cropper et al., Citation2008), take place in the national or international arena, or both, and can be both horizontal and vertical (Biermann, Citation2011). Inter-organizational relations can exhibit certain characteristics, e.g. they can be conflictive or cooperative, close or loose, symmetric or asymmetric, formal or informal and restrictive or non-restrictive (entailing costs for individual organizational autonomy or not). Even though the characteristics are presented as antagonists, they oftentimes coexist in reality. Also, different logics may prevail in particular situations or at different points in time. Given that organizations are also quite large bureaucracies, inter-organizational relations might vary when focusing on different units within organizations, when analysing interactions at different levels, e.g. inter-organizational relations at headquarters compared to those in country contexts, or when investigating particular issue areas where several organizations have a stake.

Literature on coordination among (international) organizations provides further hints regarding different types of collaborative activities. This includes for example sharing information on the ‘4Ws’: who is doing what where when. Even though sharing information on what actors are planning to do, with whom, when and what they did in the past seems to be a rather low-key activity, it has not always been an easy endeavour in the past (Woods, Citation2011). According to Hensell, information sharing as discussed by Woods is just one of three types of coordination activities. Next to information sharing, there are also sharing of resources as well as joint action (Citation2015). While sharing of resources refers to a broad range of different types including not just financial resources but also others such as knowledge, joint activities include for example data gathering or service delivery (Brinkerhoff and Crosby, Citation2002).

IOs thus engage in a range of collaborative practices. They are collaborative in the sense that they are based on organizations voluntarily conducting them with a common goal in mind and include practices that range from information sharing to sharing resources to jointly taking action. What is already evident is that some practices might be more demanding than others (e.g. information sharing requiring less than joint action), meaning that activities may differ regarding the degree of interdependence among organizations they entail and their restrictions on organizational autonomy. With regard to food security governance, Margulis (Citation2017) emphasizes that a range of different IOR can be observed, and that, interestingly, it ‘appears that inter-organizational cooperation in technical and programmatic issues (…) generate more routinized and formalized relationships’ (Citation2017, p. 516), whereas, in contrast, ‘efforts to improve global-level coherence in the global governance of food security tend to be more informal and fluid, and on the whole, do not appear to be durable over the long term’ (Margulis, Citation2017, p. 516).

While the concepts of coordination, collaboration and cooperation have a certain closeness and are sometimes used interchangeably, it is central to be clear on what they entail. I use collaboration and cooperation interchangeably to refer to a voluntary, purposeful practice between two or more IOs, who work together to achieve a common goal. Coordination has two different usages in the literature: on the one hand, coordination describes a low-key, not too-far reaching collaborative practice between two or more actors, often with the goal of basic information-sharing (e.g, Woods, Citation2011). On the other, coordination is depicted as a means to address fragmentation at the international level, or rather, its adverse effects, wherein three types can be distinguished: authoritative coordination through hierarchy, cooperative coordination in networks, and competitive coordination through markets (see Zürn and Faude, Citation2013). While the former implies a concrete activity of two or more actors, the latter refers to a more abstract phenomenon, which is still a strategy different types of actors such as states or IOs may draw on, but which is more of a process at an aggregate level. Here, I understand coordination as both: a type of collaborative practice IOs can engage in and as a mechanism through which an inter-organizational order can evolve, but not as an order in and of itself.

Inter-organizational order: coherence and division of labour

Inter-organizational order is an overarching governance structure, which entails an arrangement regarding the positions and relations among IOs and other actors in a given organizational field. Order implies a certain stability over time – while orders can and do change (and according to some must do so in order to ensure their survival, cp. Anter, Citation2004), they do not change too easily and not without a significant catalyst. An order being in place entails a certain degree of a reliability of expectations for actors who are a part of this order as well as for those who are not. An existing order reflects underlying power structures or relationships which may be to the advantage of some and the disadvantage of others; it is difficult to think about order (or its absence) without also taking the question of power into account (Anter, Citation2004). Order is not necessarily a normatively desirable outcome; an order is inherently neither ‘good’ nor ‘bad’. An inter-organizational order does not have to be the outcome of an intentional process, i.e. via active coordination efforts; rather, it can also evolve ‘spontaneously’ as a by-product of organizational interaction over time.

There are many different manifestations or types of order which can be situated on a spectrum from disorder to order and within this universe, I concentrate on two variants: coherence and division of labour. This is not to say that other kinds of order are not relevant, but rather constitutes a choice of emphasis on coherence and division of labour as those often debated in the literature (e.g. Gehring and Faude, Citation2014; Holzscheiter, Citation2014b).

On the one hand, coherence emphasizes congruence between the goals, policies, instruments and actions of different actors (Holzscheiter, Citation2014b). The organizing principle of coherence is alignment or similarity. For instance, this would entail that the policies of two or more IOs share a likeness and are not at cross-purposes with one another, and would be observable if an analysis of two IOs’ policies on a specific matter does not reveal conflicting policy advice or guidelines. Food security governance provides examples which speak more for a lack of coherence, e.g. between the FAO and the World Bank in the 1980s on the issue of agricultural development – a case of inter-organizational rivalry and diverging views on the effects of structural adjustment programmes for food security (Margulis, Citation2017).

On the other, a division of labour assigns ‘clearly defined roles to each (…) institution’ (Gehring and Faude, Citation2013, p. 127). This division of labour evolves given overlap among institutions, understood as ‘the actual or anticipated provision of similar or identical governance functions for an overlapping membership of at least two elemental institutions’ (Gehring and Faude, Citation2014, pp. 491–492), and emerges gradually over time (Gehring and Faude, Citation2013). Division of labour is accordingly based on the organizing principle of differentiation, which may take place along three main lines: First, pertaining to specific thematic aspects, be they regulatory subsets of the overall issue (Oberthür and Pozarowska, Citation2013) or concrete problems which pose themselves in a given field (Holzscheiter, Citation2014b). Second, a division of labour can take place with regard to certain governance functions, e.g. operational activities or financing (see Abbott, Citation2012). Finally, Oberthür and Pozarowska (Citation2013) also propose to include a spatial division of labour, i.e. referring to different regions throughout the world. Specifically when focusing on IOs and their operational activities, it seems to be adequate to look not just at a potential division of labour across different regions but also at a potential division of labour within regions and even within countries as it may be that some organizations concentrate on certain parts of a country. Thus, I understand division of labour to potentially occur along these three lines: sub-issues, governance functions and spatially. We may observe a division of labour if two or more IOs active within the same field differ consistently in what they do in one or all of these dimensions, e.g. one IO concentrating its operations within one specific region within a country, and another IO focusing its work on a different, specific region within the same country. Pertaining to global food security governance, in which many UN bodies are active, it appears, however, that these IOs are neither ‘nested in a hierarchal manner nor functionally specialized’ (Margulis, Citation2017, p. 510).

While important characteristics of coherence and division of labour have been advanced (e.g. the organizing principle of likeness versus one of difference), some open questions remain. For example, Holzscheiter (Citation2014b) theorizes that these two, understood as meta-governance principles, have different implications with regard to IO authority: Whereas coherence is associated with shared authority, a division of labour implicates divided authority. Thus, coherence may be less demanding and less costly with regard to organizational authority. Accordingly, we should find it more often empirically when analysing inter-organizational relations and order. If it less demanding, it might also be the type of order that develops first, with a division of labour then following at a later phase. This touches upon the question of how coherence and division of labour relate to each other. Although their organizing principles are different, one can think about possible combinations between the two: For example, there might be coherence among IOs’ goals and policies, but a division of labour or a specialization regarding instruments and activities. Regarding a division of labour, finally, it could be interesting to think about differences between sub-issues, governance functions and spatial differentiation. A spatial division of labour might be relatively straightforward and easier to reverse if an IO is not content, while it might be more costly to do so with regard to sub-issues or governance functions. Furthermore, it might be relatively speaking easier to establish a spatial division of labour than to align organizational goals and policies. This prompts the question of the degree of formalization of the division of labour, e.g. whether the division of labour is an informal practice or whether it is substantiated by agreements and contracts, such as a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU).

Exploring inter-organizational relations in food security governance: the case of Côte d’Ivoire

This section first introduces the article’s methodological approach and then elaborates on empirical observations on the field of food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire. The article employs an exploratory case study design. A case study comprises ‘the intensive study of a single case’ (Gerring, Citation2006, p. 20) and ‘the detailed examination of an aspect of a historical episode to develop or test historical observations’ (George and Bennett, Citation2005, p. 5). The case study conducted here is exploratory in nature as it applies a conceptual framework derived from the literature to the case of Côte d’Ivoire in order to develop observations on inter-organizational relations within an organizational field of food security governance at a country level. Thus, the case study is descriptive rather than causal or explanatory. I posit that this decision is justified given the lack of knowledge on inter-organizational relations in food security governance at the country rather than the global level. As Candel points out in his review of literature on food security governance, ‘a majority of the reviewed publications were of a conceptual or normative nature’ (Citation2014, p. 598), which is why further empirical investigation is important. An advantage of this approach is accordingly that it generates empirical findings from the field which further research can build on and use as a point of comparison.

An important step of case study research is case selection as a case is ‘an instance of a class of events’ (George and Bennett, Citation2005, p. 17). There are several reasons for choosing Côte d’Ivoire as a case: First, it allows for observing inter-organizational relations in a concrete country setting given that many of the operational activities of IOs in food security governance take place at the country level. Second, Côte d’Ivoire is an interesting example of a country, which has both emergency and developmental needs with regard to food security. The post-electoral crisis in 2010/2011 in particular and the associated spike in malnutrition rates led to an influx of new actors, especially international NGOs, to the organizational field of food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire. Such moments of crises and the dynamics, which follow, i.e. changes in actor configurations, can be observed at least since the political and military crisis in 2002. Crises have followed in periodic intervals ever since, the last one being the already mentioned post-electoral crisis in 2010/2011. Third, the post-electoral violence in 2010/2011 and the subsequent emergency situation also led to increased attention by donors and thus to additional funding opportunities, although not all funding requirements were met. However, this situation did not last. Today, resource constraints are pressing again and may have effects on inter-organizational relations. Fourth, there are many efforts aimed at aligning IOs’ activities at the global level, and thus, it is relevant to inquire whether and how these efforts ‘travel’ to the national level to a country like Côte d’Ivoire, or whether inter-organizational collaboration takes place independently of these global processes. While these are all reasons which speak for selecting Côte d’Ivoire as a case, the generalizability of findings to other cases nonetheless remains limited. First and foremost, the scope of this study is limited to Côte d’Ivoire, and neither analyses the global level nor can it necessarily be transferred to other country contexts.

Regarding methods, I drew on two major data sources: First, organizational documents, such as humanitarian bulletins, situation reports, country briefs, consolidated appeals, evaluations, joint letters and MoUs. Therein, a time frame from 2003 to 2016 is covered, which allows for observing whether and which changes in the organizational field take place. Second, semi-structured interviews conducted with IO staff during a research stay in Côte d’Ivoire in February/ March 2016. Taking the UN country team as a starting point, I contacted representatives of those IOs whose work had linkages to food security governance, e.g. providing food assistance, and of those entities which were specifically tasked to work on coordination within the UN system. Interview partners included (deputy) representatives, programme officers and coordination specialists, both national and international staff. Overall, I conducted eight semi-structured interviews in English or French using an interview guideline (on interviews, see e.g. Aberbach and Rockman, Citation2002; Brinkmann, Citation2014; Leech, Citation2002), which included seven themes: the set-up of the organizational field, practices of collaboration, overlap and competition, coherence, division of labour, relevance of coordination, and role of international guidelines. Data was analysed by means of a computer-assisted qualitative content analysis, which utilized a partly deductively, partly inductively generated coding scheme (Schreier, Citation2012), covering dimensions such as collaborative practices and inter-organizational order. In a first round, a sub-sample of the data was analysed to refine the coding scheme, before the revised coding scheme was then applied to the complete material. The coded material was then reviewed and analysed in-depth. Furthermore, I used network visualization software (gephi) to visualize relations between actors, based on both, interviews and organizational documents. The advantage of this approach is that it provides insights into IO perspectives on inter-organizational relations and to be sure, organizational ‘talk’ is an important component in organizational research and the emphasis in this article. However, we know that organizational ‘talk’ and ‘action’ may diverge (Brunsson, Citation1989), which is a potential bias that the approach chosen here cannot address. Yet, future research could incorporate participatory ethnographic methods, e.g. observing coordination meetings between IOs, to arrive at deeper conclusions about inter-organizational relations and order among IOs in food security governance at the country level. The remaining part of this section is structured as follows: First, I elaborate upon the organizational field of food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire, in particular upon the object, actors and their (power) relations, and norms and rules. Then, I continue by analysing the inter-organizational relations of three IOs which are at the core of the field, namely the World Food Programme (WFP), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Finally, I delve into und reflect upon coherence and division of labour as the two types of inter-organizational order of interest here.

The field of food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire

In the following, three dimensions of the organizational field of food security governance are characterized: the object, actors and their (power) relations, and the fields’ norms and rules.

The object, to begin with, is food security. That food security qualifies as such a pertinent object becomes evident in that there is a cluster in the international humanitarian architecture formed around food security. This applies to the humanitarian sphere, but food security is also a stand-alone issue area or object in development cooperation. Food security, according to the 1996 World Food Summit definition is a situation that exists ‘when all people, at all times, have physical, [social] and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food which meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’ (Bianchi, Citation2014, p. 5). The definition encompasses three main pillars: availability, access and utilization, which are hierarchically ordered, as well as a fourth pillar of stability, which covers all three main pillars over time (Barrett, Citation2013). Food security can thus be understood as a normative goal. It is a multi-faceted issue with linkages to several other issue areas, such as agriculture, health, environment/ sustainability, human rights, production/ agro-processing, trade, and finance, thus allowing for a more holistic perspective.

Second, there are numerous actors in the organizational field of food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire. This includes IOs, bilateral development agencies, international and national NGOs, as well as government entities, for example relevant ministries, and others. Regarding IOs as the focus of this article, interviewees commonly depicted FAO, UNICEF and WFP to be at the core of the field.

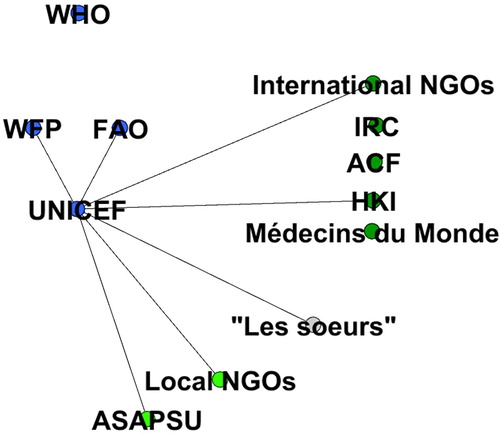

This is reflected in a description of the field by a UNICEF staff member who depicted FAO, WFP and UNICEF to be the most central IOs in the field (cf. ). While also mentioning the World Health Organization (WHO) to be a key actor, the interview partner commented at the same time on the fact that the WHO is less operationally active than the other three organizations. Next to IOs the interview partner also referred to international and national NGOs as relevant actors in the field of food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire, some of which the organization collaborates with directly. Missing in this picture are ministries, state institutions and the like which the interview partner did not refer to when asked to describe the field of food governance in Côte d’Ivoire, although the interviewee mentioned them in the course of the interview.

Figure 1: The field of food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire – a UNICEF perspective.Footnote3 Own compilation based on Interview No. 6, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, March 2016, created with gephi.

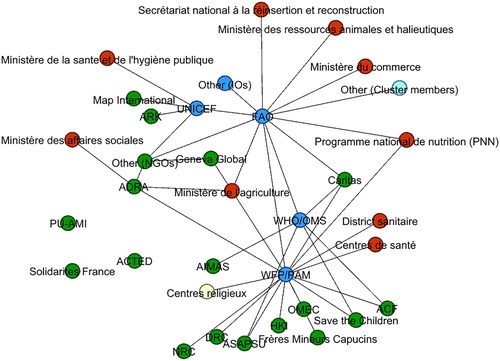

The picture gains in nuance when taking a more systemic view on the organizational field besides an individual organizational perspective. A snapshot of the field (cf. ) captures a particular moment in time: Shortly after the post-electoral violence and the subsequent humanitarian crisis in parts of Côte d’Ivoire, IOs and other actors began planning their emergency response. In that, it depicts inter-organizational relations in an emergency context without accounting for other relations between IOs and other actors in a developmental setting, which are also relevant but faded from the spotlight during the crisis in 2010/2011. As noted above, the map shows FAO, UNICEF and WFP, as well as WHO, as the four IOs of relevance, meaning that they are the organizations planning and implementing food security projects. On top of that, there are numerous NGOs that conduct activities – some without any collaboration with other actors, neither with IOs nor with government entities. The snapshot also illustrates that there are quite a number of state institutions involved, such as different ministries. For example, both FAO and WFP work together with the Ministry of Agriculture as well as with the Programme nationale de nutrition (PNN).

Figure 2: The field of food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire in 2012 – Actors.Footnote4 Own compilation based on OCHA Financial Tracking Service (OCHA, Citation2017b), created with gephi.

There are some further observations to be drawn: First, collaboration among different actors can be understood as joint action. However, they may differ regarding their characteristics. For example, a relation between an IO and an NGO can be rather asymmetrical and hierarchical if the IO delegates certain tasks to the NGO, which the NGO is required to fulfil based on a contractual basis. The links per se do not yet tell us anything about the characteristics of the collaboration or the inter-organizational relation. Second, when comparing FAO, UNICEF and WFP it appears that FAO overall collaborates more with ministries, while WFP engages with a number of NGOs. UNICEF overall has links to a ministry, NGOs and other IOs, but fewer in number than FAO and WFP. The WHO, finally, has links to NGOs and other IOs, but not to government entities. Third, there are only two government entities that have links to more than one IO: Perhaps unsurprisingly this includes the Ministry of Agriculture and the PNN. Finally, some NGOs don’t have any links to other actors, although the fact that they are on the snapshot demonstrates that they participated in the Consolidated Appeals Process (CAP) organized by OCHA and thus in coordination efforts by the international community .

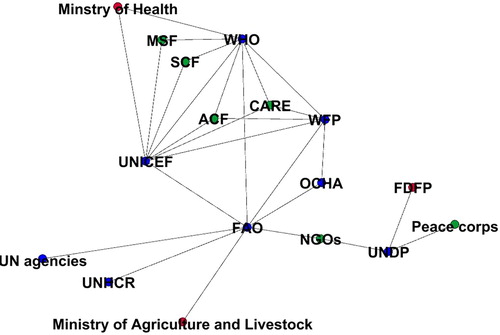

Figure 3: The field of food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire in 2003 – Actors. Own compilation based on OCHA (Citation2017a), created with gephi.

When comparing a snapshot of the organizational field of 2012 to one of 2003, there are several observations to be made: First, there are more actors involved in 2012 in comparison to 2003; the field has expanded actor-wise. Second, the number of international and national NGOs as well as government entities involved has risen: While in 2003 only the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock, the Ministry of Health and the Fonds de développement de formation professionnelle (FDFP), a state institution focusing on vocational training, were involved in food security governance, the field has diversified in 2012. The same is true of international and national NGOs: While some have remained in the country, for example Action Contre le Faim (ACF), there are numerous actors, which are part of the field in 2012, which were not in the picture in 2003. Third, interestingly, one can observe a reduction in the number of IOs in the field, with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) for example belonging to the organizational field in 2003 – here referring to the humanitarian side of food security – but not in 2012. Overall, actor configurations in the food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire have changed quite a bit in between the two snapshots from 2003 to 2012 presented here.

Regarding the power relations among the actors in the organizational field, only some tentative observations can be presented here, as power relations play out more strongly in specific inter-organizational relations among two or more actors, rather than in the organizational field overall. Nonetheless, some more general observations may be offered: First, formal authority, or the ‘legitimately recognized right to make decisions’, lies to some extent with those IOs at the core of the field. For example, FAO and WFP are the co-leads of the food security cluster. Co-leads of clusters have particular rights as well as responsibilities, as in to ‘convene or facilitate meetings of the cluster’ or in to ‘facilitate agreement on an efficient division of labour and the assignment of responsibilities amongst cluster partners’ (IASC, Citation2010). While the language of ‘facilitate’ hints at the fact that the cluster co-leads cannot enforce decisions, they are in the position to significantly shape and influence inter-organizational collaboration within the cluster. Interview partners explained that sometimes the lead IOs will agree upon an approach beforehand, and then use cluster meetings to formalize decisions in the larger, official group setting. In that sense, IOs such as FAO and WFP may have the opportunity to shape some decisions for inter-organizational relations before they are taken into the cluster. Second, actors are endowed differently with regard to resources in the organizational field of food security governance. Regarding financial resources, donors in particular are the ones with the ‘power of the purse’. But then, IOs may also have substantial financial resources, and the possibility to commission NGOs to implement projects. Within the framework of the consolidated appeals process (CAP) for instance, some IOs have received higher degrees of funding in comparison to other organizations, among them WFP, UNICEF and UNHCR as the mid-review of the 2008 CAP demonstrates ([OCHA], Citation2008b). Third, discursive legitimacy, or the ‘ability to speak authoritatively’ on a matter, is distributed differently among actors in the organizational field of food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire. WFP, for instance, enjoys recognition for its food security assessments, which are seen as the most appropriate means of measuring food security, according to one interviewee.Footnote5 To some degree, these types of power relations among IOs link back to and draw on the specific resource endowments and the legitimacy IOs enjoy at a global level. However, they do not have to translate fully to the country level, rather, power relations at the country level may be different from those at the global level. For example, an OCHA 2003 situation report on the crisis in Côte d’Ivoire does not refer to FAO in its section on food security (only WFP and UNICEF are mentioned), although at a global level FAO is the organization most commonly mentioned as it pertains to the issue of food security, together with WFP ([OCHA], Citation2003c).

Finally, there are some norms and rules that have an impact on inter-organizational relations in food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire, partly those that shape inter-organizational relations in humanitarian assistance and development cooperation overall. Two seem to be particularly salient: On the one hand, there is a strong normative requirement on inter-organizational collaboration. IOs are expected to work together, a demand that is put forward by member states, be it through channels such as the IO governing bodies or through their function as donors in humanitarian funding mechanisms, as well as by the headquarter-level, i.e. IO secretariats. This inter-organizational cooperation e.g. through the cluster system is believed to have a positive impact in humanitarian crises: According to the Terms of Reference for cluster leads, the objective is to ‘ensure a coherent and effective response’ and ‘to respond in a strategic manner’ ([IASC], Citation2013). On the other, IOs are faced with an organizing principle of the ‘comparative advantage’, which is supposed to determine which IO is particularly suited to do a certain type of activity in a certain sector and accordingly should be the one to do so. This is also reflected in the Terms of Reference’s mention of the ‘complementarity’ of humanitarian actors, and is frequently referred to by interview partners as the means of establishing which IO should engage where. Non-conformity is not appreciated: One interview partner expressed concern and disapproval that another IO was conducting income-generating activities in different locations in Côte d’Ivoire, given that the organization did not have field offices throughout the country, which could adequately monitor these projects. The interview partner felt that it was not within the IO’s mandate and in accordance within its comparative advantage to implement these kinds of projects.

International organizations and their relations

In this section, the focus will be on FAO, WFP and UNICEF, as these three IOs were most often described to be at the centre of the organizational field of food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire. There are many linkages among the three organizations and numerous instances of inter-organizational cooperation. Despite of funding constraints and limited financial resources, as becomes evident in the high resource needs formulated in the CAPs with simultaneously rather low levels of funding secured, there seems to be little competition among the three organizations. When asked whether there is competition taking place among organizations within the field, one interview partner confirmed that there is competition with regard to resource mobilization. However, the interview partner added that this refers to other UN organizations beside FAO, WFP and UNICEF, since these other organizations attempt to acquire funding but have neither the mandate to do so nor the structures in place to adequately implement these projects. Another interview partner confirmed that competition among IOs does take place, but that the competition among NGOs is even fiercer. According to interview partners, FAO, WFP and UNICEF are reacting to funding constraints through even closer collaboration, in particular by developing a joint project proposal on nutrition and mobilizing resources together rather than competing. The relations among the three IOs appear to be relatively close, and seem to be facilitated by good working relationships among the heads of the agencies, which were often referred to as an enabling factor. While the three IOs work together, it seems that the linkages between WFP and UNICEF are closer than among FAO or WFP, or among FAO and UNICEF. Whereas FAO and WFP do collaborate closely as co-leads of the food security cluster, WFP and UNICEF established an MoU as the basis of their cooperation (UNICEF & WFP, Citation2015). Although there have been discussions on establishing a FAO-WFP MoU, as WFP mentions in a 2015 country brief (WFP, Citation2015), no MoU as of yet has materialized. Thus, regarding the formal basis for the cooperation, WFP and UNICEF seem to be one step further.

FAO, WFP and UNICEF engage in numerous collaborative practices. To begin with, they are involved in information sharing. For instance, WFP conducted a cash and voucher feasibility study in Abidjan in 2011 (WFP, Citation2011), the results of which it shared with the Humanitarian Country Team, to which FAO and UNICEF belong. WFP, as head of the logistics cluster, furthermore developed an assessment of all roads and a map, which it shared with all humanitarian agencies. In that sense, by providing information WFP is enabling other humanitarian actors to conduct their activities in the first place (WFP, Citation2011). But information is not only shared through the formal cluster system, but also through informal mechanisms. One interview partner described how he would call his counterparts in other IOs to acquire the information needed to do the IO’s own planning without having to go through formal, sometimes lengthy channels. To continue, IOs are also involved in resource sharing. This can include very practical issues, for example, WFP and UNICEF sharing a sub-office in Man in Western Côte d’Ivoire (WFP, Citation2011). Finally, FAO, WFP and UNICEF also engage in joint action. While FAO and WFP work together closely in conducting food security assessments, FAO WFP and UNICEF have a history of collaborating on projects in the fields of food security and nutrition. This becomes evident in the consolidated appeals with joint projects on nutritional surveillance and rehabilitation or projects on the provision of agricultural inputs to IDPs and host communities in Côte d’Ivoire. Despite quite well-established cooperation over the years, the FAO/WFP/UNICEF joint proposal on implementing the Ivorian nutrition strategy has a new quality to it: While IOs oftentimes collaborate with other organizations in the implementation phase of a project, they do not necessarily design the projects together. For the 2016 joint proposal, this went differently. As one interview partner describes it: ‘we drafted a joint proposal for nutrition, integrated activities etc. and it is working. The proposal has been prepared and now we are doing resource mobilization together, we are presenting the document to the government’.Footnote6 Another interview partner elaborates upon the observation that the process was lengthy, but important:

I think this planning which took us many months to really sit together through joint meetings, seeing what can you do, what are you doing, what are your intervention areas-, and really making sure that we provide the synergy, I think it was extremely beneficial.Footnote7

Overall, FAO, WFP and UNICEF engage in all types of collaboration, and have inter-organizational relations, which, at least in 2016, interview partners, described quite positively in that they were said to be cooperative, close and at eye level. Even though the literature lets us expect that IOs should engage most often in information sharing, and less so in resource sharing and joint action, as they are more costly in terms of organizational autonomy, with regard to FAO, WFP and UNICEF one can observe all three types. To some extent, it seems that one can observe even more information sharing and joint action than resource sharing. However, the emphasis on joint action through a joint, inter-agency proposal is also a relatively new development and might be due to the long-standing relationships the three organizations have with each other in Côte d’Ivoire and on a global level.

Inter-organizational order: coherence and division of labour

In this remaining section, I will offer some observations on inter-organizational order in the organizational field of food security governance. As the number of actors has increased, at least in the humanitarian assistance sphere of food security, and at least for a certain period of time, the question arises as to whether the field has become ‘messier’ or not. Again, ‘messier’ does not mean that the actual outcome and impact are better or worse. These are two distinct questions. However, at least among IOs it seems to be more or less common knowledge or rather, a taken-for-granted assumption that coordination and inter-organizational cooperation are necessary to achieve more effective and efficient provision of goods and services.

At least on a discursive level, IOs frequently refer to ‘coherence’ and ‘alignment’. Therein, IOs not only strive for coherence with each other within the UN system, for example through joint strategy and planning frameworks, such as in CAPs, or in the UN Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF). The goal is also to align these strategies with government policies and strategies on the one hand, such as the Ivorian National Development Plan, as well as with international declarations on the other, for example the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in the past, or with the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) movement. Ideally, on the level of goals and policies at least, it seems as if everything should be aligned with everything. Regarding policies, one interview partner noted that there were no frictions and that policies were well aligned, since

I never found a conflictual situation regarding policies (…). Because the policies are negotiated at upper level, at headquarters, Geneva, Rome, New York, Paris whatever … (..) there is what we call the IASC, the Interagency Standing Committee, where they work on the transformative agenda (…). So I think the roles, the policies are more or less on the same direction.Footnote8

Similar to coherence, IOs frequently refer to division of labour. The organizing principle, therein, is that of the ‘comparative advantage’, with IOs highlighting the ‘complementarity’ of their efforts. This was already the case in 2003, when the UN Resident Coordinator underlined the importance of UN agencies having ‘a clear understanding of our respective roles’ (OCHA, Citation2003b). References to ‘complementarity’ are also part of later CAPs, e.g. in 2008 ([OCHA], Citation2008a), and are still frequently referred to later on. As one interview partner puts it: ‘there is some complementarity instead of overlap, unless the coordination is not working well, unless people are doing whatever they want to do, then we found that we clearly need to state who should be doing what and when.’Footnote11

If there is complementarity and the added value of each IO implies specific roles for each individual agency in food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire, how does this division of labour then look like and how has it possibly changed over time? When thinking back to the three dimensions introduced earlier on in which a division of labour may evolve – sub-issues, governance functions, and spatially – one first observation is that there are only few indications for a spatial division of labour. IOs overall focus their efforts on Western Côte d’Ivoire, where, according to their analyses, the needs for humanitarian assistance were particularly high ([OCHA], Citation2012, p. 3). Regarding different governance functions one can note that at least none among the three focal organizations in the field – FAO, WFP and UNICEF – exercises governance functions of rule-making and implementation or of financing. Rather, these IOs, as most of the others within the field, are focused on operational activities on the one hand and information and networking on the other. For instance, as it pertains to operational activities in 2012, FAO supported livelihoods and reintegration of rural households, WFP delivered emergency assistance and UNICEF provided treatment for severe acute malnutrition (OCHA, Citation2012). Regarding information and networking, all three organizations concentrate on providing information within their field of expertise as it links back to their mandate, i.e. nutrition for UNICEF and food security for WFP and FAO. However, it is not the case that one IO is responsible for implementing activities, another for providing information and so on. This leads to the third dimension, that of a division of labour along the lines of thematic sub-issues. These areas of specialization may be linked back to organizational mandates, the underlying assumption being that on the level of mandates there is no confusion regarding concrete roles and responsibilities, and no overlap. As one interview partner notes: ‘if each organization would go back to its mandate, I think it will be clear. We have mandates, each organization, we have simple mandates.’Footnote12 This goes hand in hand with the observation of another interview partner that

the division of labour [in food security governance, ah] is quite clear. In the sense that FAO really focuses on food security, longer term agricultural reforms. World Food Program is providing food assistance and also providing support in that way to the nutrition of children through the school feeding programs, the school canteens. (…) UNICEF has not a mandate on food security, (..) [the] mandate is really on nutrition.Footnote13

Responsibilities within the organizational field have changed over time ([OCHA], Citation2003a, Citation2008a, Citation2012): For instance, coordinating functions which used to be spread apart across different IOs are now mainly done by FAO and WFP. Furthermore, FAO has gained a more prominent role: Monitoring the food security situation is now mostly in its purview, together with WFP. UNICEF has mostly kept its emphasis on severe acute malnutrition, as well as on children. This does however raise the question as to how useful it is to distinguish among types of beneficiaries, as the same beneficiary groups may have different needs which fall within the mandate of different IOs. It is not clear for instance as to whether a focus on a particular group would have priority before an issue area. While it appears as if responsibilities have become more defined over time, there still remains some overlap. For example, the 2012 CAP indicates that both UNICEF and WHO are involved in the treatment of severe acute malnutrition; also, it seems as if the ‘integrated nutritional education programs’ FAO conducts could also fall within UNICEF’s sphere of responsibility.

Finally, the question arises as to whether coherence and division of labour are compatible with one another. As becomes obvious in their discourse, IOs want to achieve both at the same time, both enhanced coherence as well as a clear cut distribution of responsibilities and a delineation of specific roles. If coherence is now about the similarities of IOs, and a division of labour about their differences, are the two compatible? As mentioned earlier, it could theoretically be possible for IOs to align goals and policies, but to differentiate regarding instruments and activities. For example, IOs in food security governance commonly refer to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and their predecessors, the MDGs. To some extent, whether there is coherence or not regarding goals may depend on how abstract these goals are formulated, but then the question arises as to how useful in their everyday work such generalized coherence would be.

Overall, IOs are engaged in an ongoing process and attempt to achieve more inter-organizational order, as they are convinced of the positive effects this will have for the effectiveness of their work. At the same time, orders among IOs seem to be in flux and an object of renegotiation. Besides logics of harmonization and inter-organizational cooperation, there are also other logics which have an impact on IO action – even if IOs in their discourse say that they strive for inter-organizational order, whether or not this actually evolves (and how) remains a separate question.

Conclusion

Against a background of complexity, fragmentation and overlap attributed to food security governance at the global level, this article analysed the organizational field of food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire, as well as inter-organizational relations within the field, with particular emphasis on FAO, WFP and UNICEF. Therein, the objective of the article was to address the following research question: In how far does inter-organizational order develop in the organizational field of food security governance at the country level?

In this vein, the article provides several findings: First, the organizational field of food security governance in Côte d’Ivoire is fluid and dynamic, with actor configurations changing over time. While there was a (re)expansion on the side of NGOs and the involvement of government ministries over time, regarding IOs, a phase of concentration on select core actors has taken place. Given that the focus of this article was more on the humanitarian assistance side of food security governance, it is not surprising that NGOs have come and gone. Regarding actors, the emphasis of the article was on IOs, and most of those analysed have dual mandates, i.e. are engaged both in humanitarian assistance and development cooperation and thus are there to stay in Côte d’Ivoire for the time being. Therein, it would be fruitful to further inquire as to how the two spheres relate within the overall organizational field, and how IOs frame their operations in one way or the other. Second, inter-organizational relations among FAO, WFP and UNICEF as the three core agencies within the organizational field in Côte d’Ivoire are characterized by those involved as close and cooperative; the three organizations engage in all types of collaborative activities in pairs of two or even all three of them, and do so against a background of resource constraints. This may be specific to Côte d’Ivoire; the scope of the article is limited here to this case and does not make claims for other countries or the global level. Accordingly, further comparative research which analyses other countries may prove insightful. Third, at least on a discursive level, there are numerous references to coherence and division of labour, and IOs are engaged in many attempts to define and delineate specific spheres of responsibility and particular roles for each organization in Côte d’Ivoire. The article demonstrated that there are indications for coherence regarding goals and policies, but less so regarding instruments. Furthermore, the article showed that while there is neither a spatial division of labour, nor one along the lines of different governance functions, there are some hints for a division of labour along thematic lines. However, it appears to some extent as if it is an issue of interpretation and framing as to which activities fall within which thematic area. Thus, while there seems to be a partial, superficial consensus that there is an, albeit limited, inter-organizational order, the question appears to be more contested under the surface and the answers vary when looking into different aspects of coherence and division of labour. Here, in-depth ethnographic research on the ground would be valuable.

Overall, my article makes three contributions: First, it provides an empirical study of food security governance and inter-organizational relations at the country level and thus contributes empirical underpinnings to a literature which has so far focused more on conceptual and normative work (Candel, Citation2014). Second, and in a related vein, my article demonstrates that food security governance at the country level – at least pertaining to the case of Côte d’Ivoire – does not appear to be as dire, fraught and conflictive as global food security governance sometimes appears to be. Within limits, coherence and a division of labour do appear to evolve to a certain degree, and inter-organizational relations seem to be fairly cooperative. While there are few case studies of inter-organizational relations in food security governance at the country level, the article’s findings do speak to Margulis’ (Citation2017) assumption that cooperation in technical and programmatic issues – in this case, at the country level – lead to more routine and longer-term inter-organizational relations, than more informal and short-term attempts at coherence between at the global level. Finally, the article illustrates that coherence and division of labour as types of inter-organizational order need to be carefully considered, as an analysis of their various dimensions points to different answers of whether we can observe such an order. In essence, the question of whether there is an inter-organizational order between IOs in food security governance (or not) requires a nuanced view of these different dimensions and clear criteria against which to assess them – a task to which the article hopes to have provided first observations and points of entry for further inquiry.

Notes on contributor

Angela Heucher is a doctoral candidate at University of Potsdam and a research affiliate at the Berlin Graduate School for Transnational Studies. From 2014 to mid-2018, she worked as a research associate at the Collaborative Research Center (SFB) 700 “Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood” in a research project examining the role of international organizations as external governance actors (“‘Talk and Action’: How International Organizations Respond to Areas of Limited Statehood”). The project analyzed how international organizations see their own role as well as opportunities and challenges regarding their operations in different country contexts. Her research interests include international organizations, inter-organizational relations, as well as organizational perceptions of and responses to fragmentation and overlap in global food security governance.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Research for this article was conducted when the author worked as a researcher at the Collaborative Research Center (SFB) 700 ‘Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood’ in the research project ‘“Talk and Action”. How International Organizations Respond to Areas of Limited Statehood’. Funding by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under grant SFB 700/3, D08 is gratefully acknowledged. Furthermore, I thank the three anonymous reviewers for valuable and constructive comments.

2 While inter-organizational order is often seen as a solution to developments such as fragmentation or overlap, I have no prior assumptions in this regard. The existence of a division of labour among IOs, for example, does not automatically have to lead to a more effective and efficient provision of governance goods. Rather, this is an empirical question.

3 The figure includes all actors the UNICEF interviewee referred to, either generically (‘international NGOs’) or by name (Helen Keller International – HKI). Lines indicate that UNICEF cooperates with another actor in a specific project or someway else. The color code blue depicts IOs (mostly UN), while green stands for international and local NGOs and grey depicts the category ‘other’.

4 The figure builds on the Consolidated Appeals Process (CAP), a document which the OCHA compiles when a humanitarian emergency is declared, cf. OCHA (Citation2012). The document lists projects by cluster/sector. All projects were included which had a food security governance component and which referred to food security as a goal in the project description. Relations among actors depict that they jointly engage in the implementation of a project (category on ‘implementation partners’). The colour codes are as follows: blue – IOs; green – NGOs; red – state institutions; yellow – other.

5 IO-Interview No. 07, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, March 2016.

6 IO-Interview No. 05, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, March 2016.

7 IO-Interview No. 06, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, March 2016.

8 IO-Interview No. 03, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, February 2016.

9 IO-Interview No. 07, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, March 2016.

10 IO-Interview No. 03, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, February 2016.

11 IO-Interview No. 05, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, March 2016.

12 IO-Interview No. 03, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, February 2016.

13 IO-Interview No. 06, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, March 2016.

14 IO-Interview No. 05, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, March 2016.

References

- Abbott, K. W., 2012, ‘The transnational regime complex for climate change’, Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, Vol. 30, No. 4, pp. 571–590.

- Aberbach, J. D. and B. A. Rockman, 2002, ‘Conducting and coding elite interviews’, Political Science & Politics, Vol. 35, No. 4, pp. 673–676.

- Anter, A., 2004, Die Macht der Ordnung: Aspekte einer Grundkategorie des Politischen, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

- Barrett, C. B., 2013, Food or consequences: Food security and its implications for global sociopolitical stability, in C. B. Barrett, ed, Food Security and Sociopolitical Stability, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–34.

- Bianchi, E. 2014. Food Security, the Right to Food and the Human Development Report 1994 (GR:EEN Working Paper No. 48), University of Warwick.

- Biermann, R., 2011, Inter-organizational relations: An emerging research programme, in B. Reinalda, ed, The Ashgate Research Companion to Non-State Actors, Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 173–184.

- Brinkerhoff, D. W. and B. Crosby, 2002, Managing Policy Reform: Concepts and Tools for Decision-Makers in Developing and Transitioning Countries, Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press.

- Brinkmann, S., 2014, Unstructured and semi-structured interviewing, in P. Leavy, ed, The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 277–299.

- Brunsson, N., 1989, The Organization of Hypocrisy: Talk, Decisions and Actions in Organizations, Chichester: Wiley.

- Candel, J. J. L., 2014, ‘Food security governance: A systematic literature review’, Food Security, Vol. 6, No. 4, pp. 585–601.

- Clapp, J., 2014, Food and hunger, in T. G. Weiss, ed, International Organization and Global Governance, London: Routledge, pp. 644–655.

- Clapp, J. and M. J. Cohen, 2010, The food crisis and global governance, in J. Clapp, ed, The Global Food Crisis: Governance Challenges and Opportunities, Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, pp. 1–10.

- Cropper, S., M. Ebers, C. Huxham and P. Smith Ring, 2008, Introducing inter-organizational relations, in S. Cropper, M. Ebers, C. Huxham and P. Smith Ring, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Inter-Organizational Relations, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–21.

- DiMaggio, P. J. and W. W. Powell, 1983, ‘The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields’, American Sociological Review, Vol. 48, No. 2, pp. 147–160.

- Dingwerth, K. and P. Pattberg, 2009, ‘World politics and organizational fields: The case of transnational sustainability governance’, European Journal of International Relations, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 707–743.

- FAO. 2013. FAO's Attributes, Core Functions and Comparative Advantages. (No. CL 144/14 Web Annex). Rome.

- Franke, U. and M. Koch, 2017, Sociological approaches, in J. A. Koops and R. Biermann, eds, Palgrave Handbook of Inter-Organizational Relations in World Politics, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 169–187.

- Gaus, A. and J. Steets, 2012, The challenging path to a global food assistance architecture, in A. Binder, C. B. Barrett and J. Steets, eds, Uniting on Food Assistance: The Case for Transatlantic Cooperation, Abingdon, OX: Routledge, pp. 11–29.

- Gehring, T. and B. Faude, 2013, ‘The dynamics of regime complexes: Microfoundations and systemic effects’, Global Governance, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 119–130.

- Gehring, T. and B. Faude, 2014, ‘A theory of emerging order within institutional complexes: How competition among regulatory international institutions leads to institutional adaptation and division of labor’, The Review of International Organizations, Vol. 9, No. 4, pp. 471–498.

- George, A. L. and A. Bennett, 2005, Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Gerring, J., 2006, Case Study Research: Principles and Practices, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Hensell, S., 2015, ‘Coordinating intervention: International actors and local ‘partners’ between ritual and decoupling’, Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 89–111.

- Holzscheiter, A., 2014a, ‘Interorganisationale Harmonisierung als sine qua non für die Effektivität von Global Governance?: Eine soziologisch-institutionalistische Analyse interorganisationaler Strukturen in der globalen Gesundheitspolitik’, Politische Vierteljahresschrift, Sonderheft, Vol. 49, pp. 322–348.

- Holzscheiter, A., 2014b, Restoring order in global health governance. Do metagovernance norms affect interorganizational convergence? (CES Papers Open Forum No. 23). Cambridge, MA.

- IASC. 2010. ‘Operational guidance: Generic terms of reference for cluster coordinators at the country level’, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/system/files/documents/files/IASC20Operational20Guidance20ToR20Cluster%20Coordinators.pdf.

- IASC. 2013. ‘Generic terms of reference for sector/cluster at the country level’, https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/legacy_files/IASC20Generic20ToR20for20Cluster20Leads20at20the20Country%20Level_0.pdf.

- Koch, M., 2014, ‘Weltorganisationen: Ein (Re-)Konzeptualisierungsvorschlag für internationale Organisationen’, Zeitschrift Für Internationale Beziehungen, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 5–38.

- Krasner, S. D., 1983, Structural causes and regime consequences: Regimes as intervening variables, in S. D. Krasner, ed, International Regimes, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, pp. 1–21.

- Leech, B. L., 2002, ‘Asking questions: Techniques for semistructured interviews’, Political Science & Politics, Vol. 35, No. 4, pp. 665–668.

- Margulis, M., 2013, ‘The regime complex for food security: Implications for the global hunger challenge’, Global Governance, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 53–67.

- Margulis, M., 2017, The global governance of food security, in J. A. Koops and R. Biermann, eds, Palgrave Handbook of Inter-Organizational Relations in World Politics, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 503–525.

- McKeon, N., 2015, Food Security Governance: Empowering Communities, Regulating Corporations, Abingdon, OX: Routledge.

- Oberthür, S. and J. Pozarowska, 2013, ‘Managing institutional complexity and fragmentation: The Nagoya Protocol and the global governance of Genetic Resources’, Global Environmental Politics, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 100–118.

- OCHA, 2003a, Côte d'Ivoire Plus Five: Consolidated Inter-Agency Appeal, Geneva: OCHA.

- OCHA. 2003b. Côte d'Ivoire: Côte d'Ivoire: Better protect, better assist: 16 May 2003, http://reliefweb.int/report/cC3B4te-divoire/cC3B4te-divoire-better-protect-better-assist.

- OCHA. 2003c. ‘Crisis in Côte d'Ivoire Situation Report No. 06’, https://reliefweb.int/report/cC3B4te-divoire/crisis-cC3B4te-divoire-situation-report-no-06.

- OCHA. 2008a. Côte d'Ivoire Consolidated Appeal, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/system/files/documents/files/cap_2008_cdivoire_1.pdf.

- OCHA. 2008b. ‘Côte d'Ivoire Consolidated Appeal: Mid-Year Review’, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/system/files/documents/files/myr_2008_cdivoire.pdf.

- OCHA. 2012. Côte d'Ivoire Consolidated Appeal, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/system/files/documents/files/cap_2012_cdi_eng_1.pdf.

- OCHA. 2017a. ‘Financial Tracking Service: Tracking humanitarian aid flows [Côte d'Ivoire + 5 2003 (CAP)]’, https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/123/summary.

- OCHA. 2017b. ‘Financial Tracking Service: Tracking humanitarian aid flows [Côte d'Ivoire 2012 (CAP)]’, https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/380/summary.

- Pfeffer, J. and G. R. Salancik, 2003, The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective, Stanford, CA: Stanford Business Books.

- Phillips, N., T. B. Lawrence and C. Hardy, 2000, ‘Inter-organizational collaboration and the dynamics of institutional fields’, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 23–43.

- Schreier, M., 2012, Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Schwindenhammer, S., 2017, ‘Global organic agriculture policy-making through standards as an organizational field: When institutional dynamics meet entrepreneurs’, Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 1–20.

- UNICEF, & WFP. 2015. Mémorandum d’Entente entre Le Fonds des Nations Unies pour L’Enfance et le Programme Alimentaire Mondiale en Côte d’Ivoire.

- Vetterlein, A., 2012, ‘Seeing like the World Bank on poverty’, New Political Economy, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 35–58.

- Vetterlein, A. and M. Moschella, 2014, ‘International organizations and organizational fields: Explaining policy change in the IMF’, European Political Science Review, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 143–165.

- WFP. 2011. Côte d'Ivoire Post-electoral Crisis: Côte d'Ivoire External Situation Report #10 [20 June 2011]. WFP.

- WFP. 2015. Côte d'Ivoire Brief [Reporting Period: 01 January - 31 March 2015]. WFP.

- Woods, N., 2011, Rethinking aid coordination, in H. J. Kharas, K. Makino and W. Jung eds,Catalyzing Development: A New Vision for Aid, Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, pp.112–126.

- Zürn, M. and B. Faude, 2013, ‘Commentary: On fragmentation, differentiation, and coordination’, Global Environmental Politics, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 119–130.