ABSTRACT

Within the migration-development nexus, cooperation with immigrant organizations is often considered useful by governments and aid agencies. Due to acquaintance with home-country conditions and capacity to transfer remittances, migrants are increasingly viewed as contributors to aid and development. The Swedish government has a similar approach and views migrants and their associations as an asset. At the same time, research on home-country activities among Swedish immigrant organizations (SIOs) is scarce and little is known about their contributions. Based on qualitative and quantitative data on publicly funded SIOs, we explore the alignment between their activities and the Swedish policy goals of humanitarian aid and development cooperation. While few activities align directly, other activities align indirectly since they mainly reflect sectoral targets of the policy goals. We also find few cases of formalized and systematic collaboration with Swedish aid financiers. In comparison with cooperation practices in other European contexts, this suggests deficits in terms of professionalization of SIOs, marginalization in development cooperation and lack of opportunity structures for SIOs. Few SIOs are also engaged in home-country development and humanitarian assistance. A possible explanation is the institutional role that immigrant organizations historically have been granted in the Swedish context. If these deficits are addressed, SIOs could potentially enhance the Swedish approach to aid and development assistance.

Introduction

The migration-development nexus has received increased attention in recent years and is often argued to have a significant impact on international development (Faist and Fauser, Citation2011; Piper, Citation2017). This is evident in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Agenda 2030 where migration and development are intertwined, potentially altering traditional views on aid and development assistance (cf. IOM, Citation2018). The potential of migration for development are not limited to remittances being sent back to developing contexts on an individual basis, but also includes migrant communities (Gagnon and Khoudour-Castéras, Citation2011; OECD, Citation2016). Research demonstrates that migrants maintain strong ties to their home-countries through transnational communities engaging in activities with implications for development (Levitt and Glick Schiller, Citation2004; Portes, Citation2015). Such activities may include social work, poor relief or business collaboration, at times coordinated and implemented by immigrant organizations in host-countries (Østergaard-Nielsen, Citation2009; Portes and Zhou, Citation2012). Hence, cooperation or ‘co-development’ with immigrant organizations is often considered useful in host countries (Nijenhuis and Broekhuis, Citation2010; Portes, Citation2015) and has been launched in order to adapt more efficiently to the SDGs (IOM, Citation2019a). At the same time, such cooperation does not follow a blueprint. Rather, immigrant organizations’ co-development activities and structures of cooperation seem to vary greatly, particularly among European countries (de Haas, Citation2006; Portes and Fernández-Kelly, Citation2015).

To further explore the ties that bind immigrant organizations to aid and development, we present a study on Swedish Immigrant Organizations’ (SIOs) development activities and their engagement in humanitarian assistance.Footnote1 Sweden is a relatively prominent country, both as a receiving country of migrants and as a donor of development assistance in proportion to its economy. Thus, it constitutes an interesting case for research on co-development involving immigrant organizations. The population in Sweden amounts to around 10.45 million, of which some 20 per cent are born in another country. When including second-generation migrants (Swedish-born with two foreign-born parents) the number of people with foreign descent reaches around 26 per cent of the total population (Statistics Sweden, Citation2021).Footnote2 Sweden also presents a historic presence of formally organized immigrant organizations, with state-support since 1975 (Byström and Frohnert, Citation2017), and some 70 per cent of migrants between 1969 and 2014 have been classified as circular migrants, moving between Sweden and countries of birth (Statistics Sweden, Citation2016). Finally, Sweden has for long been among the leading per capita donors of overseas development assistance (OECD, Citation2019), but has not been included in major international studies on transnationalism that trace engagement of immigrant organizations in home-country development (cf. de Haas, Citation2006; Portes and Fernández-Kelly, Citation2015; Pries and Sezgin, Citation2012).

Research on SIOs and their engagement in aid and development is scarce. Earlier studies indicate that such activities are quite limited – only a few cooperation programs exist and little is known about their role (Kleist, Citation2018; Olsson, Citation2016). Moreover, these studies often focus on particular groups of migrants; hence, there is a need for more comprehensive analyses across different groups and organizations. To better grasp their engagement and the possibility of expanded state-SIO cooperation in aid and development, we present findings based on data from official annual reports and interviews with organization-leaders pertaining to 53 organizations, across migrant groups, that received state-funding in 2017. We first assess levels and types of activities among the SIOs and further analyse these activities in terms of (a) their alignment and misalignment with the Policy Framework for Swedish Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Assistance (hereinafter, PSDH); and, (b) in comparison with co-development practices by immigrant organizations in other European cases. It should be noted that we are here primarily focusing on European cases since immigrant organizations in these contexts, like Sweden, regularly receive state support (Portes, Citation2015). Thus, our work is guided by the following inquiries: To which extent and in which ways do SIOs engage in activities pertaining to development and humanitarian aid? How do these activities align and misalign with key objectives in the PSDH; and which aspects might impact on found levels and types of activities, particularly in light of immigrant organizations’ positioning in other European cases?

We find that a minority of SIOs in our sample are engaged in development and humanitarian assistance, and we identify few cases of formalized and systematic collaboration with Swedish aid financiers. Moreover, while a rather limited number of activities align directly with objectives in the PSDH, other activities align indirectly as they mainly reflect sectoral targets of the policy goals. In comparison with cooperation practices in other European contexts, our findings furthermore suggest deficits in terms of professionalization of SIOs and lack of opportunity structures for co-development. We propose that such deficits largely stem from an ambiguous, institutionalized role of immigrant organizations in the Swedish political context, and a comparatively marginalized position in development cooperation. The latter becomes particularly clear in comparison with other Swedish civil society organizations (CSOs) that are, like immigrant organizations in the Spanish case, involved from the very beginning of development planning and implementation, while annually receiving a significant portion of the Swedish development assistance budget (Sida, Citation2021b).

Hence, we identify untapped resources that could, albeit in a modified structure of elevated state-SIO cooperation, enhance Swedish development assistance and humanitarian aid work. Finally, to realize the assumptions of the migration-development nexus in Agenda 2030 and the SDGs, our findings – pertaining to one of the largest per capita donors in overseas development assistance – indicate that states in donor-countries could potentially benefit from analysing particular modes and structures to enhance formal incorporation of migrants and their organizations.

Background and political context of SIOs

Immigrant organizations have existed in Sweden since the mid-1800s. The first organizations date back to 1830 and were formed by migrants from Finland. Since the 1960s, the presence of migrants has increased and Sweden currently hosts a plethora of associations and migrant communities (Dahlstedt, Citation2003). Politically, the purpose of hosting immigrant organizations in Sweden reflects the notion of multiculturalism (cf. Dahlström, Citation2004). This means that migrants have the opportunity to preserve their cultural specificity and the organizations should enable them to do so. To obtain state funding, the organizations should therefore be formed on ‘ethnic grounds’ and at least 51 per cent of the members should be of foreign descent (MUCF, Citation2021).

The autonomy of SIOs has allegedly been crippled by a political process that Schierup (Citation1991) labels ‘ethnization’. According to Schierup, the idea of multiculturalism in Sweden is essentially a political construct that has been orchestrated from above by giving immigrant organizations a standardized role as proponents of ethnic interests within the broader framework of civil society. In the context of Swedish corporativism where civil society organizations (CSOs) historically have been amalgamated with the state, immigrant organizations have turned into a layer of loyal state clients whose primary role is to justify a vision of multiculturalism that has little to do with their own ambitions. This suggests that their capacity to voice their own interests is limited and that they primarily have served the objectives of the state (Schierup, Citation1991).

Schierup’s critique has been widely debated in previous research on SIOs (cf. Dahlstedt, Citation2003; Odmalm, Citation2004), and a common interpretation is that Swedish organizations differ from equivalents in other countries which are assumed to be more independent (Emami, Citation2004; Scaramuzzino, Citation2013). At the same time, the strength of corporativism has varied and some periods have been characterized by a lower degree of earmarking of state aid to the organizations (Borevi, Citation2004). Due to the growing demand for partnerships with CSOs in delivery of public services, today’s governance structure also enables horizontal relationships with Swedish authorities (Government of Sweden, Citation2009; Scaramuzzino, Citation2013). While this weakens the argument that SIOs lack autonomy, research on their capacity of collaborating with authorities suggests that many are hampered by the legacy of government-sponsored multiculturalism (Odmalm, Citation2004). Aggravated by the fact that the state has protected their members through various forms of social benefits, this has allegedly made it difficult to assume new responsibilities (Scaramuzzino, Citation2013).

While these aspects may thwart the capacity to engage in home-country activities, migrants in Sweden have generally had unrestricted opportunities for transnationalism. The right to preserve origin, mother tongue, and contacts with home countries was specified already in the commission on immigrants that commenced in 1968 (Borevi, Citation2004). Current information technology also facilitates cross-border activities. Home country issues can, for instance, be raised in social media and involve members of the same diaspora in other countries as well as younger associates (Bloch and Hirsch, Citation2018). Despite this, existing research indicates that the frequency of transnational activities has been low among SIOs. In a survey from 2000-2001, only a small portion had this type of engagement whereas ethnocultural activities and activities pertaining to integration dominated (Dahlstedt, Citation2003).

The Swedish policy on development cooperation and humanitarian assistance

The Swedish approach to international development covers both humanitarian assistance and long-term development cooperation. The objectives are stated in the PSDH which reflects the Swedish endorsement of Agenda 2030 and related international agreements like the Addis Ababa Agenda on Financing for Development (2015), the Paris Agreement on Climate Change (2015) and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Management (2015), but also priorities of specific concern for Sweden (Government of Sweden, Citation2016a). To ensure that the PSDH is implemented and coordinated among ministries and public agencies, the government has issued a specific policy for global development (officially known as the PGU) covering both domestic responsibilities and international strategies (Government of Sweden, Citation2015).

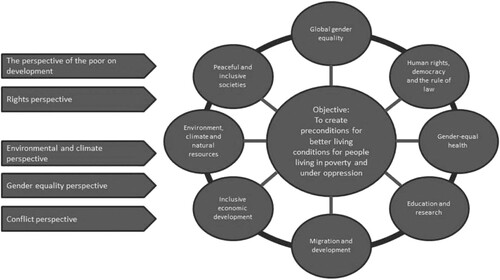

The approach to development cooperation revolves around five major perspectives (Government of Sweden, Citation2016a; Sida, Citation2020a). These are (1) ‘the perspective of the poor on development’ (stating that the fight against poverty in development intervention must draw on a multi-dimensional approach where social as well as economic reasons to poverty are considered from a bottom-up perspective), (2) ‘the rights perspective’ (stating that the emphasis on democracy and human rights in development intervention must empower people to acknowledge and defend their rights), (3) ‘the conflict perspective’ (stating that development intervention must reflect and take conflict prevention and peacebuilding into consideration), (4) ‘the gender equality perspective’ (stating that development intervention must address and take gender inequality as well as sexual and reproductive rights into consideration), and (5) ‘the environmental and climate perspective’ (stating that development intervention must contribute to sustainability and resilience to climate change).

The perspectives relate to the targets of Agenda 2030 but are also influenced by ideas that reflect Sweden’s role and voice in international development more specifically. Among those are the Feminist Foreign Policy launched in 2014 in order to clarify Sweden’s position in the global advocacy for women’s rights (cf. OECD, Citation2019). There are also fields of interest where the government claims that Agenda 2030 requires additional efforts. This applies, for instance, to the perspective on human rights, democracy and rule of law where Sweden’s ambitions are stronger in terms of priorities and long-term goals (Government of Sweden, Citation2016a). While these perspectives comprise the basics of the policy framework, eight additional themes are specified in the PSDH in order to concretize where development cooperation is necessary. As demonstrates, each theme will contribute to the overarching goal of the policy framework, i.e. ‘to create preconditions for better living conditions for people living in poverty and under oppression’.

Figure 1. The perspectives of Swedish development cooperation (retrieved from Government of Sweden, Citation2016b, p. 17)

Humanitarian assistance is primarily aimed for immediate response in case of e.g. natural disasters, armed conflicts or food shortages. In this sense, there is a difference between long-term development cooperation and actions taken during humanitarian emergencies (Sida, Citation2020b). However, since the realization of long-term development goals is believed to mitigate the impact of humanitarian emergencies the approach to humanitarian assistance is associated with the overarching framework of development cooperation. A key objective of the PSDH is therefore to create synergies between short-term humanitarian intervention and long-term cooperation.

Research on co-development and comparative cases

While diasporic communities can mediate resources for development in collaboration with home country governments (cf. Fenton et al., Citation2020; Gelb et al., Citation2021), co-development was initially understood as means to reduce push factors in sending areas and prevent further migration. Even if the outcome is uncertain and determined by the institutional capacity of using of diasporic transfers on the ground (OECD, Citation2017), the idea of relying on migrants for other developmental ends has gradually received more traction (Khoudour-Castéras, Citation2009; Nijenhuis and Broekhuis, Citation2010). This has been driven by an interest in the benefits of the migration-development nexus, especially in European countries (Gagnon and Khoudour-Castéras, Citation2011; Sinatti and Horst, Citation2015). Despite the intricacies of associating a group of migrants with a specific geographical space, co-development is often considered important due to migrants’ pre-existing acquaintance with language and conditions in their country of origin (Nijenhuis and Broekhuis, Citation2010; Sinatti and Horst, Citation2015). Similar ideas are prevalent among Swedish policy-makers. In compliance with the SDGs, the PSDH declares that migrants and their associations are ‘development agents’ with ‘unique knowledge about needs and opportunities in their countries of origin’. Accordingly, ‘migrants’ and ‘diaspora groups’ should be recognized and supported within the framework of development cooperation (Government of Sweden, Citation2016a, p. 34).

At the same time, the outcome and organization of co-development differ across countries. In settings where the state financially supports co-development initiatives, the outcome may be crippled by competition over recognition and funding from the authorities or clientelism that motivates organizations to prioritize financial entitlements more than efforts on the ground (Portes, Citation2015). A further obstacle seems to be that governments in host countries have streamlined the process of cooperation in ways that exclude immigrant organizations lacking organizational skills of conventional development organizations. This implies that the added value of collaboration occasionally is jeopardized and that the organizations may lose motivation due to lack of recognition (Nijenhuis and Broekhuis, Citation2010). Another problem is that state funding occasionally makes it difficult for organizations to find other economic means of sustaining their activities during cutbacks in public spending (Cebolla-Boado and López-Sala, Citation2015). In this sense, state support could also lead to dependency that obstructs organizations from realizing their ambitions. Finally, the advantages of collaboration may be hampered by misalignments between restrictive immigration policies and co-development objectives (Khoudour-Castéras, Citation2009). The idea that co-development should prevent further migration has therefore been associated with a legitimization of immigration control instead of incorporation and collaboration with migrants for developmental ends (Gagnon and Khoudour-Castéras, Citation2011).

Despite these uncertainties, fruitful outcomes have appeared in contexts where governments have invited migrants to play an active role. A case in point is France where co-development policies have created room for a range of home-country activities, particularly by Moroccan organizations (Lacroix, Citation2009). Such activities include infrastructure development, practical and economic support to returning migrants, new forms of cooperation in tertiary education and joint undertakings between NGOs and immigrant organizations. Efforts that enhance professionalization and capacity to cooperate with other actors have been critical in this respect, and paved the way for undertakings that reflect co-development policies both in France and in the home country. Moroccan migrants have also established NGOs engaged in smaller self-financed undertakings such as delivery of medicine, school materials and money transfers from charities. While interventions on the ground are less common among these organizations, available sources indicate that the activities are beneficial to the areas where they reach out (Lacroix and Dumont, Citation2015).

A similar commitment is discernible in Spain where co-development policies have evolved gradually since the early 2000s (Østergaard-Nielsen, Citation2009). Spanish organizations are treated as legitimate stakeholders in the administration of the state and have a firm position as strategic partners in official development assistance. As a consequence, independent and charity-based activities occur less regularly whereas mainstream development undertakings like capacity building, business development, projects for women’s empowerment and infrastructural development are common. Such undertakings often rely on a well-established network of collaboration partners and many organizations are headquartered in the home country (Cebolla-Boado and López-Sala, Citation2015). This suggests that they are embedded in the conventional structure of international development and have a function similar to that of an NGO in terms of assisting donors and aid agencies. Like the French case, therefore, Spanish cooperation practices underscore the significance of professionalization and the importance of treating immigrant organizations as legitimate partners.

Examples from Belgium indicate that co-development policies can be successful, particularly in terms of capacity building and institutional development in home countries. Through collaboration with migrants such initiatives have been conducted in countries like Burundi, DRC, and Rwanda (Godin et al., Citation2015; IOM, Citation2004). Public funding for co-development has also paved the way for ‘institutional opportunity structures’ (Godin et al., Citation2015, p. 201) for migrants to engage in home country development. However, with the state lacking a thorough commitment in terms of providing equal access to these structures, it is mainly associations with integrated members that have reaped the benefits. This is notable among Moroccan migrants whose engagement in co-development correlates with their level of social and political integration. In addition, demands on co-financing and fragmentation among funding agencies due to federal administrative structures have allegedly hampered the process (Godin et al., Citation2015). Besides the importance of creating wider opportunity structures, this suggests that a generous and well-defined system of funding is needed to mobilize migrants for developmental ends.

Research from the Netherlands demonstrates that co-development programs are available there, but mainly for migrants from countries that match the priorities of official development policy (Nijenhuis and Broekhuis, Citation2010). Moreover, a limited number of organizations appear to be solidly funded by state authorities while charity-related work and small-scale projects through ad hoc funding are common. The Dutch case is characterized by variances in terms of access to co-development programs. This is visible in the differences between Ghanaian, Surinamese and Moroccan migrants, where the first group has a stronger affiliation with co-development programs. Consequently, Ghanaian organizations have more resources and can engage in larger development projects than other groups (Nijenhuis and Zoomers, Citation2015, p. 249). Organizations engaged in co-development are also more professionalized and embedded in the financial and operational structure of other donors. Moreover, their participation in national networks for migration and development is higher and many have connections with the government that contribute to their position (Nijenhuis and Zoomers, Citation2015). Similar to the Belgian case, this suggests that access to institutional opportunity structures is unevenly distributed and that the Dutch commitment to co-development is weaker in comparison with the French and Spanish cases.

As noted earlier, research on Swedish cooperation practices is scarce. By comparison, therefore, little is known about the Swedish approach. The most renowned examples are the Somalia Diaspora Programme (SDP) and the Swedish-Somali Business Programme (SSBP). Targeting gender equality, job creation, human rights and sustainable development, these programs are exclusively focusing on Somalia – a major recipient of Swedish aid. Projects within SDP and SSBP have primarily been carried out by formally registered Somali-Swedish organizations. While professionalization has been ensured through mandatory training programs, associates of the organizations have often been active in Swedish politics or have maintained political connections in Somalia. Like the previous examples, engagement in co-development therefore seems associated with political and institutional integration. Somali-Swedish organizations are also engaged in activities that relate to health, schooling and supply of water. Such activities differ from Swedish development priorities and are usually funded by other donors, member fees or donations (Kleist, Citation2018). While this provides a hint of SIOs home-country activities, our findings demonstrate that development-related work exists among other migrant groups as well. Comparatively, our sample included four organizations of Somalian descent and their activities comprised around 18 per cent of the total number of reported development activities.

Data and methodology

Our data consists of annual reports from 52 SIOs submitted to the Swedish Agency for Youth and Civil Society (MUCF) in 2017.Footnote3 The reports contain organizational data from the previous year and must be submitted yearly to obtain funding from the state. Besides information about members, date of establishment and financing, they include facts about ongoing projects, activities and collaboration partners. As such, they are useful in order to grasp the organizations’ key features and operations. The content was initially coded in a database comprising both numerical and qualitative data. Leaving out non-ethnic federations of immigrant organizations and organizations failing to submit a report (only one for the year of 2017), the sample represents all but 6 of the publicly funded ‘ethnic associations’ at national level in Sweden.

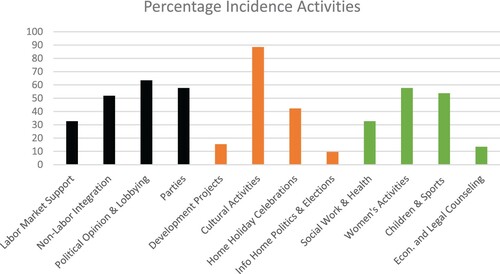

To analyse organizational characteristics, information from the database was tabularized based on key data such as number of members and local organizations, annual budgets, and year of establishment. This data was analysed with descriptive statistics. The activities in the annual reports were mapped based on the twelve activities with the highest frequency. These were subsequently organized into four types of host-country activities, four types of home-country activities, and four types that we categorized as member services. Among host-country activities we included labour market support, non-labour integration, political opinion/lobbying, and parties and festivities, while home-country activities included development projects, cultural activities with home-country orientation, home-country holiday celebrations, and information on home-country politics and elections. Among member services, we included social work and health services, women’s activities, children’s and sports activities, and economic and legal counselling (see ).

To get further insights, semi-structured interviews were carried out with chairpersons of the organizations or other key informants with knowledge about the organization at the national level. Compared to the annual reports, information from the interviews often stretched further back in time and gave a denser description that involved both past and present undertakings. This made it possible to better grasp the span of activities over a longer time-period among interviewed organizations. In total, 17 interviews were conducted, including one with the organization that was discarded in the statistical inquiry due to lack of an annual report. In addition, a written answer to the interview guide was received from one organization which means that 18 SIOs were investigated in this part of the study. Finally, we analysed SIOs’ activities in co-development with Sida and other development organizations in Sweden by way of archive research that included project databases.

In light of the mixture of data sources, it is important to note that our material does not allow for generalizations about SIOs. Furthermore, our research covers only state-funded, national organizations while the total number of migrant associations in Sweden is much larger. While some activities have been cross-verified through supplementary sources, follow-up studies in the home-countries have not been conducted. In this respect, our findings cannot say anything about the impact or effectiveness of the undertakings.

Organizational features and types of engagement

As noted above, state-funding requires at least 51 per cent of members to have immigrant background, activities should be non-profit and the organization must have at least 1,000 paying members either nationally or at local levels (MUCF, Citation2021). Pioneer organizations in our sample were founded during the post-World War II period, while the majority were established between 1991 and 2000. By comparison, the most recent SIOs were established between 2011 and 2013. SIOs in our sample have on average been active in Sweden for 23 years, and total number of members ranges from 244 to 8662. They have on average 18 local organizations and a balanced representation of female and male members.Footnote4 Moreover, around 73 per cent of the organizations are small with only 15 per cent in our sample categorized as large, and around 12 per cent as very large. Annual reports show that SIOs receive limited financial support from the state – median annual benefit is approximately 300,000 SEK (about USD 35,500)Footnote5 which on average amounts to roughly 70 per cent of an organization’s total budget.

As incidence rates show in , SIOs are in aggregate predominantly engaged in cultural activities. This is followed by activities related to political parties, opinion and lobbying for home country issues in Sweden, and various types of social engagement including women’s activities, children and sports. By comparison, the incidence of engagement in labour market support is significantly lower. Yet, SIOs are often engaged in activities that relate to integration. This includes, for instance, training in the Swedish language which in some cases is an indirect form of labour market support.

Development activities and alignment with Swedish policy priorities

The number of home-country development projects is low and such undertakings were reported by a mere 15.4 per cent. At the same time, conducted interviews indicate charitable work, such as shipping of goods and other forms of home-country support, to be fairly common, particularly when considering both past and present undertakings. Thus, a combination of data from annual reports and interviews indicates further engagement of this type. Of the total number of investigated SIOs, 19 organizations report that they are or have been engaged in projects or other activities that relate to development or humanitarian aid. Our inquiry implies that these activities are ongoing or have been undertaken during the past ten years, while a few took place as early as the mid-2000s. All but four of the organizations are linked to recipient countries of Swedish development assistance (OECD, Citation2021; Sida, Citation2021a). The remaining four are linked to countries that formerly belonged to the Soviet Union, the Eastern Bloc and Yugoslavia, and joined the European Union during the 2000s (see ).

Table 1: Alignment with Swedish development priorities (based on data in SIOs’ annual reports and interviews with organizational leaders).

To shed light on SIOs’ activities, draws on a qualitative assessment where information from the annual reports and the interviews have been compared with the objectives of each theme in the PSDH.Footnote6 In relation to the global gender equality theme, for instance, we have included activities that promote the interests of women in the home country or in the geographical area associated with the diaspora. As such activities may influence gender relations at various levels, they are also assumed to be linked to the global gender equality theme. Some organizations are also categorized based on activities that seem to deviate from the themes of the PSDH. These are listed under ‘other development areas’ in . Such activities may still be conducive to development but the extent to which they serve the key priorities of the PSDH is unclear in this case. As we will explain below, many of them rather contribute indirectly since they primarily reflect sectoral targets in the prioritized goals.

Activities of direct concern for the PSDH

Three SIOs reported activities pertaining to the overarching goals of the gender equality theme to support the rights of women, to counteract all forms of discrimination, and to make sure that women are treated in accordance with CEDAW (1979) and other international agreements that Sweden has ratified. SIO 1 has educated people in women’s rights in places where the security level is safe for its people to operate. These undertakings were managed in partnership with a Swedish study association and also included training in human rights. In this respect, their work does not only correspond to the gender equality theme but also to the theme that includes human rights in the policy framework (see more below). SIO 2 has provided training in gender equality and environmental awareness in the home country with financial support from the Swedish government. Due to the engagement in environmental issues, these activities are also relevant for more than one theme in the policy framework (see more below). While these SIOs have a Swedish counterpart and have been active at the field level, SIO 3 states that they primarily contribute with financial donations to locally arranged projects. In this way, the organization has recently financed the construction of an atelier that makes it possible for women to make a living under war-torn conditions. This project would probably also fit with the gender equality theme, particularly considering CEDAW’s emphasis on economic opportunities for women.

Similar to the first example above, two additional SIOs report activities related to the theme of human rights, democracy and the rule of law. This theme is a key priority of Swedish development cooperation and includes extensive support of human rights as well as support of democratic governance, democratic institutions and constitutional law based on democratic principles. SIO 5 reports that they have worked with electoral assistance during the home country’s first elections. The undertakings involved training of electoral observers and were carried out in partnership with a local organization. SIO 4 have at least two associated undertakings. The first of those pertain to a project where members of the organization educate local aid workers in the processes of democracy. The project is financed by a Swedish aid organization and also includes training in HIV prevention. The second project aims to establish a venue in the home-country’s capital where schooling in democracy and the principles of Swedish associational life will take place. The venue also aims to become a safe space for returnees and a forum for teaching in security issues. Due to the emphasis on security, these ambitions may also correspond to the theme that relates to peaceful and inclusive societies. This is indicated by the Swedish endorsement of the New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States (2011) and UN Security Council Resolutions 1325 and 2250 (2000, 2015) which relate to such activities, and thus constitute important features of this theme.

While activities directly associated with research are lacking in our sample, some organizations prioritize schooling of young people. Hence, such activities are indirectly associated with the education and research theme which states that schooling is a human right and a prerequisite for democracy, equity and sustainable development. Found schooling activities have mostly been limited to financial donations, or donations of educational material to schools in the home-country. However, SIO 6 has also been involved on the ground, participating in the construction of a school. The project was carried out in partnership with a Swedish aid financier and members of the organization were assigned to make sure that local partners followed agreements. While these undertakings correspond to the significance of education in the policy framework, they also indicate that young people are important when the organizations engage in development work. This is not only visible in the context of schooling but in the number of organizations that engage in youth development, care of children, orphans and disabled children (see ).

As noted previously, some organizations have activities associated with the theme related to environment, climate and natural resources. Priorities of this theme include support for sustainability in the use of natural resources, to create awareness of environmental problems and to strengthen the role of CSOs in efforts to enhance transparency and accountability in matters of environmental concern. In addition to the previous example, undertakings related to this theme were reported by two organizations. While members of SIO 10 have been engaged in eco-tourism on local farms in the home – country, SIO 9 has recently invited local environmental activists to inform about deforestation and environmental crimes allegedly committed by Swedish businesses in the home-country. This latter activity primarily aims to benefit development in the home-country by giving voice to local activists. Possibly, therefore, it aligns the government’s emphasis on local civil society actors as catalysts for transparency and accountability in matters related to sustainability.

Humanitarian assistance

Several organizations report activities that can be defined as humanitarian assistance. Here, SIOs provide emergency response in the wake of natural disasters like flooding, drought and earthquakes, conflict or food shortages. Assistance is often provided in the form of goods or collective remittances gathered from members and other private donors, for example during a festivity, and then sent to the home country. SIO 3 reports occasional assistance through food distribution and hygiene products, shipped out of Sweden in containers. In terms of transfers, SIO 1 and 11 states that money is remitted via the ICRC and Doctors Without Borders, whereas the other often rely on local organizations they seem to know and trust. In other cases, funds are occasionally being transferred and managed by the diaspora at the global level or, due to lack of reliable bank connections, by members travelling to the home country. The fact that some organizations appear to engage autonomously through local connections could potentially benefit the policy goals of humanitarian assistance. According to the PSDH, there is currently a strong demand for enhanced coordination and influence of local actors in order to make humanitarian intervention more need-based and effective. In this regard, the organizations could potentially contribute with local knowledge and connections. The channelling of collective remittances may also have benefits beyond the sphere of humanitarian aid. When diaspora organizations act as mediators of remittances for a common purpose, transfers are sometimes larger in comparison with other types of remittances and may have wider economic implications on the ground (cf. Gelb et al., Citation2021). As we will show below, such undertakings are fairly common among organizations with activities that deviate from the Swedish policy goals.

Activities in other development areas

Several organizations have engagements that we define as ‘other development areas’. As noted previously, such activities differ from the PSDH and are difficult to categorize based on the main themes. As demonstrates, the first category concerns youth development, care of children, orphans and disabled children. SIO 14 and 16 are working with capacity building among deprived youngsters in the home country, while the other put emphasis on orphans or children with disabilities assisted through money collections to local aid organizations or schools for disabled children. While the PSDH generally addresses young people as a subsidiary objective in relation to broader development goals, these activities seem to address young people per se. Most of them also focus on specific beneficiaries like vulnerable and disabled children and seem to prioritize direct relief more than the socio-political targets of the PSDH. Yet, as aid of this type may contribute to socio-political development, they could potentially support the broader policy scheme indirectly.

Among ‘other development areas’, we have also identified activities that relate to food production and agriculture, an area not addressed among main priorities by the Swedish government. Rather, the government’s engagement with food and agriculture primarily relates to the necessity of adapting to climate change in order to prevent food shortages. Linkages are also found in the emphasis on inclusive economic development which the government views as a prerequisite for the goals that relate to food security and eradication of hunger in Agenda 2030. Activities in this category were reported by two organizations. In the first case, members of SIO 7 are trying to enhance living conditions in the home country through minor undertakings like purchasing agricultural products from locals or buying agricultural machines and small pieces of land to individuals who need it. In the second case, SIO 3 has participated in the construction of a bakery in the home country which secures bread delivery to around 400 families. Both initiatives derive from a process where needs have been defined and addressed based on contacts with local organizations or personal connections with people on the ground. Given that the government mainly treats food security and agriculture as subsidiary objectives in relation to other priorities, these activities could probably only provide a partial contribution to the PSDH. Defining them in terms of indirect support may thus be reasonable also in this case.

A further activity in this category is infrastructure development, which is not a major concern of the PSDH but rather constitutes a subsidiary objective in the theme related to inclusive economic development. In this context, transportation and communication facilities are viewed as prerequisites for fair trade and sustainable investments. Engagement in infrastructural projects was reported by one of the organizations (SIO 9), and mainly concerns co-funding of road projects in the home country. This has been managed by members who collect money in Sweden for a global fund aimed at reconstruction and development in the wake of conflicts and natural disasters. While infrastructure development constitutes a sub-target for the Swedish government, it may indirectly contribute to the broader policy goals.

A related area concerns business development in the home countries. Like infrastructure development, such undertakings are not addressed directly by the PSDH but appear in relation to the goal of inclusive economic development. While economic growth is important in this respect, the main priorities of the PSDH relate to sustainable growth and investments that contribute to social and political goals like the rule of law, good institutions, inclusion and gender equality. The organizations engaged in business development have worked predominantly with Swedish companies and seem to have priorities that differ from the idea of inclusive economic development. While SIO 5 has mediated contacts between a Swedish air carrier and local business partners with the aim of establishing flights to the home country, SIO 4 states that they are trying to boost economic growth at home by paving the way for Swedish businesses and investors. The aim, according to the representative, is to give them competitive advantages by being the first to market once the country is safe enough for foreign investments. Even if these activities may contribute to economic growth in the home country, none of the organizations stated or implied that inclusive or sustainable growth would be the goal of their activities. In this sense, the undertakings are only contributing partially to the broader goals of the PSDH since they may enhance growth.

As demonstrates, some organizations are engaged in activities that relate to care. These activities are often targeted towards hospitals in the home country, for instance through purchasing and delivering used healthcare equipment from Sweden. Similarly, care of elderly is a prioritized area. SIO 17 has been engaged in running retirement homes while SIO 18 is engaged in advocacy for older people in the home country. As with youth development, these activities are directed towards undertakings or groups that lack specific recognition in the PSDH but occur in a subsidiary fashion. While elderly people and hospitals are not targeted explicitly in the policy framework, such priorities mainly occur in the theme of gender equal health where the right to health allegedly concerns ‘everyone’ (Government of Sweden, Citation2016a, p. 37). Thus, while issues like sexual and reproductive health, women’s rights and LGBTQ individuals are more important for the government in this respect, indirect linkages between the PSDH and the work of the organizations are discernible in this case too.

In summary, a limited number of SIOs’ activities appear to be directly aligned with the PSDH, and many undertakings have a rather loose coupling where they contribute but partially or indirectly to the policy framework through various forms of collective remittances or other independent initiatives. Consequently, our findings suggest that a general alignment does not exist between the work of the SIOs and the goals of the PSDH. At the same time, it would be inaccurate to dismiss SIOs’ development activities since their alignment becomes somewhat stronger when the prospect of co-development is approached more broadly by considering both direct and indirect linkages. A further observation is that many activities appear to be small and insignificant in relation to the broader goals of the PSDH. As previously noted, however, there is a demand for local actors and organizations in the operative structure of Swedish development cooperation where they could play an important role in terms of raising environmental awareness, and in the stated quest for need-based and effective humanitarian intervention. The PSDH also calls for greater diaspora engagement in social remittances, e.g. transfers of political ideas and skills obtained in Sweden, and further economic interaction between migrants and home countries. Beyond the positive impact this might have on development, such activities are also assumed to prevent further migration and enhance the possibilities of voluntary returns. Once these additional aspects are thoroughly considered, stronger synergies may exist for a potential future alignment between the goals of the PSDH and the activities we have identified.

Structural constraints

Despite these possibilities, our results indicate that SIOs’ engagement in development and humanitarian aid is rather modest. Only a few SIOs report such activities while the main share of their engagements takes place within Swedish borders. Occasionally, this could be explained by political reasons that prevent collaboration and contacts with home-countries. Immigrant organizations may sometimes represent interests that challenge the foreign policy of host countries, and they can also be barred from entering the home country if their members are at odds with the regime (Huynh and Yiu, Citation2015; Olsson, Citation2016). Due to previous experiences of political and economic turmoil, they may also distrust development initiatives by home country governments (OECD, Citation2016). In combination with obstacles like travel precautions, such reasons were sometimes perceived as a barrier to transnational activity among the interviewed SIOs. A further and perhaps more important explanation pertains to their role as state clients. As noted above, researchers have often viewed SIOs’ position within the framework Swedish multiculturalism as a barrier to independent action. For instance, Odmalm (Citation2004, p. 113) argues that immigrant organizations are obliged to remain loyal to the authorities and act for the ‘greater good’ to receive public funding. Accompanied by the requirement of adjusting to the organizational principles of Swedish associational life, this has allegedly blocked activities that deviate from what the organizations think the state is expecting.

From this perspective, the limited engagement could possibly be explained by the institutional role SIOs have been granted in the Swedish context. Hence, whereas the most common activity in our data – cultural activities – serves the political objectives of Swedish multiculturalism, engagement in development and humanitarian aid rather appeal to home country loyalties and are less common because such activities may be at odds with this role. The same could possibly be said about the other activities we have identified. Apart from lobbying for home country issues, celebration of home country holidays and dissemination of information about home-country politics and elections, the remaining activities primarily seem to address issues of concern for migrants within Sweden. Structurally, therefore, many SIOs are seemingly caught in a formula of activities that pertains to host country interests and may prevent transnational undertakings on a wider scale. This was also confirmed in the interviews where SIOs often perceived themselves not as transnational actors per se, but predominantly as Swedish CSOs with the foremost task of preserving the cultural distinction of their members while also contributing to integration.

These barriers are possibly reinforced by the official approach to co-development which seems equally inhibited by structural constraints, particularly through a lack of coordination across departments and the paradoxical state-assigned role of SIOs. While MUCF, the state agency responsible for funding of SIOs, employ criteria for state-funding that fail to address co-development efforts (and rather emphasize preserving ethnic identity and participation in Swedish society), the PSDH which guides Swedish development cooperation and aid, calls for greater involvement of migrants. Yet, the PSDH remiss did not go out to a single SIO for review before being adopted by the Swedish government, implying that SIOs were marginalized already in the formation of the country’s development objectives (cf. Government of Sweden, Citation2016a, pp. 58–60).

Marginalized partner

While co-development practices may exist on a wider scale than presented here, our study could identify but a few SIOs that are affiliated with Swedish aid financiers, and only a handful of externally financed development projects. Apart from the partnership with organizations of Somalian descent, most development activities are seemingly undertaken without systematic and formalized collaboration. Considering the prevalence of enabling parameters and that nearly all of the organizations with development activities are linked to countries of significance for Swedish aid, this suggests that Sweden aligns with the cases of the Netherlands or Belgium where the lack of institutional opportunity structures seems to prevent co-development on a wider scale. The lack of opportunity structures could be contrasted with the formalized and quite advanced development cooperation between the Swedish state and other CSOs. This is further evident in the apparent mismatch of funding sources that inevitably inhibit SIOs’ development activities. MUCF, the agency constituting the largest funding agency for SIOs, provides roughly 25 million SEK (about USD 3 million) annually or an average of 313,000 SEK (about USD 37,000) per SIO for all types of activities, while Sida provides close to 1.8 billion SEK (about USD 213 million) for development assistance through CSOs as Strategic Partners. However, the list of Strategic Partners fails to include any SIO (Sida, Citation2021b), and the latter are only sporadically involved in work carried out by selected Strategic Partners like ForumCiv which received over 260 million SEK (about USD 31 million) in 2020 from Sida to perform development activities (ForumCiv, Citation2021).

Comparing Sweden with other European cases also indicates that enhanced professionalization of SIOs is needed for co-partnership to flourish. This presents a challenge as SIOs often lack the professional skills of other public sector partners and have been reported elsewhere to find it difficult to comply with formalities that characterize collaboration with the authorities (Kleist, Citation2018; Scaramuzzino, Citation2013). As noted previously, professionalization of migrant organizations has been vital in Spain and France where co-development strategies are more integrated in official development policy. Given the practice of turning immigrant organization into legitimate stakeholders, the Spanish case is particularly interesting in this respect. Even if SIOs often prioritize activities that differ from the PSDH and have identified needs that deviate from the Swedish policy targets, the government could draw from best practices in such contexts in order to enhance SIOs’ professional capabilities and further explore the prospect of cooperation.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that roughly 35 per cent of SIOs engage in some form in development assistance and aid activities. Rather than larger projects, most SIOs provide development support for their home-countries in an ad-hoc fashion. That is, they seldom participate in official development projects funded by Sida or its strategic partners, where only a handful of SIOs contribute. The analysis of SIOs’ activities in relation to the PSDH reveals that few activities align directly with Swedish development priorities, although several activities do align indirectly.

We suggest that the relatively low levels of cooperation could be traced to a set of structural constraints, where SIOs activities possibly are inhibited by a paradoxical, state-provided role and lack of coordination between state agencies. SIOs are generally neither viewed nor treated as important partners in Swedish development efforts, which manifests itself both in terms of limited funding and marginalization from partnerships. Accordingly, the Swedish case aligns quite well with the Belgian and the Dutch case where co-development is partly being pursued without sufficient opportunity structures. It also misaligns with that of immigrant organizations in Spain, and to a lesser degree France, two countries that have a more formalized and systematized development cooperation with immigrant organizations.

At the same time, we discern potential for future enhancement of SIO-involvement in Swedish development assistance and aid. Such partnerships would arguably benefit SIOs, whose enhanced role could ensure adequate funding and possibilities for professionalization of their organizations, while most likely improving Swedish aid collaboration through local knowledge and potentially larger untapped networks in home countries. Hence, the Swedish government may opt in the future to use established co-development agreements and practices with CSOs, and experiences in other European countries, as roadmaps for enhanced engagement of SIOs.

Finally, immigrant organizations in other donor countries may constitute untapped resources, like in the case of Sweden. Continued strengthening of the migration-development nexus should arguably not overlook the potential of immigrant organizations to spur local development, and findings in the Swedish case could be used in future international assessments and planning for aid partnerships.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Axel Fredholm

Axel Fredholm is Senior Lecturer at the Department of Sociology, Lund University, Sweden. His research mainly covers development studies, migration, education policy and Swedish school politics.

Johan Sandberg

Johan Sandberg is Associate Professor (Docent), Department of Sociology at Lund University and Research Fellow at the Center for Migration and Development (CMD), Office of Population Research at Princeton University. His research has been published in journals such as Development and Change, Ethnic and Racial Studies, Development Policy Review, Social Policy & Administration, and Global Social Policy.

Olle Frödin

Olle Frödin is Associate Professor (Docent) in Sociology at Lund University. His research interests mainly concern globalization, governance, labor market change and migration.

Notes

1 The terms immigrant organization, diaspora and migrant are used interchangeably in this article. Conceptually, we are following IOMs definition which states that diasporas are ‘migrants or descendants of migrants, whose identity and sense of belonging have been shaped by their migration experience and background’ (IOM, Citation2019b). We define immigrant organizations as organized groups of migrants with activities that may influence both home countries and host countries, or other geographical areas associated with the group.

2 In December 2021, the total population reached 10,452,326. Of these, the number of foreign-born comprised 2,090,503 while the number second-generation immigrants comprised 662,068 (Statistics Sweden, Citation2021).

3 For an overview of included organizations, see in Appendix. According to the public business register in Sweden, all organizations are still operational. A majority have also received public funding for the year of 2021 (MUCF, Citation2022).

4 For organizational features, see in Appendix.

5 All currency conversions in this article are based on the exchange rate on July 1, 2017 (SEK to USD).

6 Since the assessment includes interview data, SIOs have been anonymized in order to protect confidentiality of the informants.

References

- Bloch, Alice and Shirin Hirsch, 2018, ‘Inter-generational transnationalism. The impact of refugee backgrounds on second generation’, Comparative Migration Studies, Vol. 6, No. 30, pp. 1–18.

- Borevi, Karin, 2004, Den svenska diskursen om staten, integrationen och föreningslivet, in Bo Bengtsson, ed, Föreningsliv, makt och integration. Rapport från Integrationspolitiska maktutredningens forskningsprogram, Stockholm: Justitiedepartementet, pp. 31–64.

- Byström, Mikael and Pär Frohnert, 2017, ‘Invandringens historia – från “folkhemmet” till dagens Sverige’, DELMI Kunskapsöversikt, Vol. 2017, p. 5. https://www.delmi.se/publikationer/kunskapsoversikt-2017-5-invandringens-historia-fran-folkhemmet-till-dagens-sverige/. Date: 8.9.2021.

- Cebolla-Boado, Héctor and Ana López-Sala, 2015, Transnational immigrant organizations in Spain: Their role in development and integration, in Alejandro Portes and Patricia Fernández-Kelly, ed, The State and the Grassroots. Immigrant Transnational Organizations in Four Continents, New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 264–290.

- Dahlstedt, Inge, 2003, Invandrarorganisationer i Sverige, in Flemming Mikkelsen, ed, Indvandrerorganisationer i Norden, København: Nordisk Ministerråd/Akademiet for Migrationsstudier i Danmark, pp. 27–94.

- Dahlström, Carl, 2004, Nästan välkomna. Invandrarpolitikens retorik och praktik, Göteborg: Göteborgs universitet. Date: 7.9.2021.

- de Haas, Hein, 2006, ‘Engaging Diasporas. How Governments and Development Agencies Can Support Diaspora Involvement in the Development of Origin Countries’, https://heindehaas.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/2006-engaging-diasporas.pdf. Date: 6.9.2021.

- Emami, Abbas, 2004, Institutionaliserade relationer, fria organisationer – om sverigeiraniers föreningsliv, in Bo Bengtsson, ed, Föreningsliv, makt och integration. Rapport från Integrationspolitiska maktutredningens forskningsprogram, Stockholm: Justitiedepartementet, pp. 163–196.

- Faist, Thomas and Margit Fauser, 2011, The migration–development nexus: toward a transnational perspective, in Thomas Faist, Fauser Margit and Kivisto Peter, ed, The Migration-Development Nexus. Migration, Diasporas and Citizenship Series, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–26.

- Fenton, Nina, Jason Gagnon, Christoph Weiss and Laura Wollny, 2020, Remittances and financial sector development in Africa. In Banking in Africa. Financing Transformation Amid Uncertainty, Luxembourg: European Investment Bank, pp.183–204. https://www.eib.org/attachments/efs/economic_report_banking_africa_2020_en.pdf. Date 22.5.2022.

- ForumCiv, 2021, ‘Medlemsorganisationer’. https://www.forumciv.org/sv/medlemskap/medlemsorganisationer. Date: 8.9.2021.

- Gagnon, Jason and David Khoudour-Castéras, 2011, ‘Tackling the Policy Challenges of Migration. Regulation, Integration, Development’, OECD Development Centre, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/tackling-the-policy-challenges-of-migration_9789264126398-en. Date 22.5.2022.

- Gelb, Stephen, Sona Kalantaryan, Simon McMahon and Marta Perez-Fernandez, 2021, ‘Diaspora Finance for Development: From Remittances to Investment’, Publications Office of the European Union, https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC125341. Date 22.5.2022.

- Godin, Marie, Barbara Herman, Andrea Rea and Rebecca Thys, 2015, Moroccan and Congolese migrant organizations in Belgium, in Alejandro Portes and Patricia Fernández-Kelly, ed, The State and the Grassroots. Immigrant Transnational Organizations in Four Continents, New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 189–211.

- Government of Sweden, 2009, ‘En politik för det civila samhället. Regeringens proposition 2009/10:55’, https://www.regeringen.se/49b70c/contentassets/626c071c353f4f1d8d0d46927f73fe9c/en-politik-for-det-civila-samhallet-prop.-20091055. Date: 7.9.2021.

- Government of Sweden, 2015, ‘Politiken för global utveckling i genomförandet av Agenda 2030. Regeringens skrivelse 2015/16: 182’, https://www.regeringen.se/49bbd2/contentassets/c233ad3e58d4434cb8188903ae4b9ed1/politiken-for-global-utveckling-i-genomforandet-av-agenda-2030-skr.-201516182.pdf. Date: 7.9.2021.

- Government of Sweden, 2016a, ‘Policyramverk för svenskt utvecklingssamarbete, Regeringens skrivelse 2016/17:60’, https://www.regeringen.se/4af25d/contentassets/daadbfb4abc9410493522499c18a4995/policyramverk-for-svenskt-utvecklingssamarbete-och-humanitart-bistand.pdf. Date: 7.9.2021.

- Government of Sweden, 2016b, ‘Policy Framework for Swedish Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Assistance’, https://www.government.se/49a184/contentassets/43972c7f81c34d51a82e6a7502860895/skr-60-engelsk-version_web.pdf. Date: 7.9.2021.

- Huynh, Jennifer and Jessica Yiu, 2015, Breaking blocked transnationalism: Intergenerational change in homeland ties, in Alejandro Portes and Patricia Fernández-Kelly, ed, The State and the Grassroots. Immigrant Transnational Organizations in Four Continents, New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 160–186.

- IOM, 2004, ‘MIDA. Mobilizing the African Diasporas for the Development of Africa’, https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/mida_en.pdf. Date: 25.5.2022.

- IOM, 2018, ‘Migration and the 2030 Agenda. A Guide for Practitioners’, https://publications.iom.int/books/migration-and-2030-agenda-guide-practitioners. Date: 3.9.2021.

- IOM, 2019a, ‘Migration, Integration, Development. Bolster Inclusion to Foster Development’, https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/migration_integration_development.pdf. Date: 6.9.2021.

- IOM, 2019b, ‘Glossary on Migration’, https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml_34_glossary.pdf. Date: 23.5.2022.

- Khoudour-Castéras, David, 2009, ‘Neither Migration nor Development: The Contradictions of French Co-development Policy’, http://umdcipe.org/conferences/Maastricht/conf_papers/Papers/Neither_Migration_nor_Development.pdf. Date: 7.9.2021.

- Kleist, Nauja, 2018, ‘Somali Diaspora groups in Sweden – engagement in development and relief work in the horn of Africa’, Delmi Rapport, Vol. 2018, p. 1. https://www.delmi.se/media/0bzbyy5w/delmi-report-2018_1-eng.pdf. Date: 6.9.2021.

- Lacroix, Thomas, 2009, ‘Transnationalism and development: The example of Moroccan migrant networks’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Vol. 35, No. 10, pp. 1665–1678.

- Lacroix, Thomas and Antoine Dumont, 2015, Moroccans in France: Their organizations and activities back home, in Alejandro Portes and Patricia Fernández-Kelly, ed, The State and the Grassroots. Immigrant Transnational Organizations in Four Continents, New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 212–235.

- Levitt, Peggy and Nina Glick Schiller, 2004, ‘Conceptualizing simultaneity: A transnational social field perspective on Society’, The International Migration Review, Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 1002–1039.

- MUCF, 2021, ‘Etniska organisationer’, https://www.mucf.se/bidrag/etniska-organisationer. Date: 6.9.2021.

- MUCF, 2022, ‘Årsredovisning 2021’, https://www.mucf.se/publikationer/arsredovisning-2021. Date 23.5.2022.

- Nijenhuis, Gery and Annelet Broekhuis, 2010, ‘Institutionalising transnational migrants’ activities. The impact of co-development programmes’, IDPR, Vol. 32, No. 3-4, pp. 245–265.

- Nijenhuis, Gery and Annelies Zoomers, 2015, Transnational activties of immigrants in the Netherlands: Do Ghanaian, Moroccan and Surinamese Diaspora organizations enhance development?, in Alejandro Portes and Patricia Fernández-Kelly, ed, The State and the Grassroots. Immigrant Transnational Organizations in Four Continents, New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 236–263.

- Odmalm, Pontus, 2004, Invandrarföreningar som intressekanaler – möjligheter och hinder på lokal nivå, in Bo Bengtsson, ed, Föreningsliv, makt och integration. Rapport från Integrationspolitiska maktutredningens forskningsprogram, Stockholm: Justitiedepartementet, pp. 99–128.

- OECD, 2016, ‘Perspectives on Global Development 2017. International Migration in a Shifting World’, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/perspectives-on-global-development-2017_persp_glob_dev-2017-en. Date: 22.5.2022.

- OECD, 2017, ‘Interrelations between Public Policies, Migration and Development’, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/interrelations-between-public-policies-migration-and-development_9789264265615-en. Date: 23.5.2022.

- OECD, 2019, ‘OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews: Sweden 2019’, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/oecd-development-co-operation-peer-reviews-sweden-2019_9f83244b-en. Date: 6.9.2021.

- OECD, 2021, ‘Sweden, in Development Co-operation Profiles’, https://doi.org/10.1787/8a6be3b3-en. Date: 7.9.2021.

- Olsson, Erik, 2016, ‘‘Diaspora - ett begrepp i utveckling. En kunskapsöversikt’. Delmi’, Rapport, Vol. 2016, pp. 4. http://delmi.se/upl/files/133677.pdf. Date: 6.9.2021.

- Østergaard-Nielsen, Eva, 2009, ‘Mobilising the Moroccans: Policies and perceptions of transnational co-development engagement among Moroccan migrants in Catalonia’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Vol. 35, No. 10, pp. 1623–1641.

- Piper, Nicola, 2017, ‘Migration and the SDGs’, Global Social Policy, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 231–238.

- Portes, Alejandro, 2015, Immigration, transnationalism and development. The state of the question, in Alejandro Portes and Patricia Fernández-Kelly, ed, The State and the Grassroots. Immigrant Transnational Organizations in Four Continents, New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 1–24.

- Portes, Alejandro and Patricia Fernández-Kelly, 2015, eds, The State and the Grassroots. Immigrant Transnational Organizations in Four Continents, New York: Berghahn Books.

- Portes, Alejandro and Min Zhou, 2012, ‘Transnationalism and Development: Mexican and Chinese immigrant organizations in the United States’, Population and Development Review, Vol. 38, No. 2, pp. 191–220.

- Pries, Ludger and Zeynep Sezgin, 2012, Cross Border Migration Organizations in Comparative Perspective, Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Scaramuzzino, Roberto, 2013, I statens tjänst. Så påverkas invandrarorganisationer av politiska krav och förväntningar, Stockholm: Sektor3.

- Schierup, Carl-Ulrik, 1991, ‘Ett etniskt Babels torn: Invandrarorganisationerna och den uteblivna dialogen’, Sociologisk Forskning, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 3–22.

- Sida, 2020a, ‘Prioriteringar i biståndet’, https://www.sida.se/Svenska/sa-fungerar-bistandet/svenskt-bistand/prioriteringar-i-bistandet/. Date: 7.9.2021.

- Sida, 2020b, ‘Två sorters bistånd’, https://www.sida.se/sa-fungerar-bistandet/tva-sorters-bistand. Date: 7.9.2021.

- Sida, 2021a, ‘Sida i världen’, https://www.sida.se/sida-i-varlden. Date: 7.9.2021.

- Sida, 2021b, ‘Civilsamhället och organisationer’, https://www.sida.se/partner-till-sida/civilsamhallet-och-organisationer. Date: 8.9.2021.

- Sinatti, Giulia and Cindy Horst, 2015, ‘Migrants as agents of development: Diaspora engagement discourse and practice in Europe’, Ethnicities, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 134–152.

- Statistics Sweden, 2016, ‘Välfärd 3/2016’, https://www.scb.se/contentassets/bd478fd453084f998296cab9f7f2ccd9/le0001_2016k03_ti_a05ti1603.pdf. Date: 6.9.2021.

- Statistics Sweden, 2021, ‘Befolkningsstatistik i sammandrag’, https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/population/population-composition/population-statistics/pong/tables-and-graphs/yearly-statistics–the-whole-country/summary-of-population-statistics/. Date: 23.5.2022.

Appendix

Table A1: SIOs’ organizational features (based on data in SIOs’ annual reports).

Table A2: Overview of included organizations.