Abstract

The relevance of political science education and research in the conduct of elections is evident, but their actual roles are not. We zero in, specifically, on the contribution of political science education and research to peaceful polling in Kenya and Zimbabwe. In both countries, electoral violence has accompanied multi-party competition. To get a profile of political science scholarly production and impact, from a comparative perspective, particularly research output on electoral violence, we employ bibliometric analyses covering publications from the whole African continent. Web of Science and Sabinet databases provide a reliable picture of a fair amount of elections expertise in Kenya and Zimbabwe. In order to approach the role of political scientists in the countries’ electoral politics as well as their participation, or lack of it, in public engagement and public decision-making, we have conducted semi-structured interviews of political scientists working in universities there. Our study reveals structural obstacles related to the ethnicization of political power in Kenya and the economic decline in Zimbabwe. Although academic qualifications were respected and the faculty enjoyed freedom to express opinions on political issues, self-censorship and frustration were identified as hampering the ability of scholars to enhance peaceful polling.

Introduction

The linkage between political science and electoral politics is indispensable. Liberal democracy with elections and electoral competition are central topics in political science (Berndtson, Citation1991, p. 98). African academics’ experiences and scientific output of the transitions to majority rule and multi-party competition are particularly interesting in this regard, not least due to the prevailing problem of electoral violence in the region. Political science is one of the oldest and, in terms of the student intake, biggest disciplines in the main African universities. Thus, research conducted in political science is well-established and has also covered the conduct of elections there. The intensity, value and use of such research, however, is not a given. Comparative studies elsewhere on the content and impact of political science have noted the increasing influence of demand-driven research agendas (Bandola-Gill et al., Citation2021), but also the difficulties of theoretically and methodologically driven research work to show its practical relevance (Stoker et al., Citation2015).

Much of the research work conducted in African universities has been linked to practical policy, not least because of the context of a developmentalist state or interests of the foreign donor agencies. However, there is little systematic analysis on the impact of African political science research on the actual political developments there. Partly, this reflects the focus on training of civil servants, but perhaps also the fact that academic freedoms already early on were restricted by colonial dependencies and authoritarian governments (Mazrui, Citation1975).

Analyses of the evolution of the political science discipline in Africa have appeared, for instance, in the collections The Teaching and Research of Political Science in Eastern Africa (Oyugi, Citation1989) and Political science in Africa (Barongo, Citation1983). Researchers have noted the contribution of the discipline in democratisation (Mustapha, Citation2006), yet also been critical about political scientists using their expertise to serve the interests of undemocratic regimes (Ibrahim, Citation1998). The aim of this article is to contribute to this literature by shedding light on the content of political science research in Africa and its potential to have an impact in one specific area, that of electoral policy. We focus on Kenya and Zimbabwe, countries where competitive elections have been marred by electoral violence, and look at the possible contribution of local electoral violence research to peaceful polling.

Our assumption is that production and dissemination of knowledge on the conduct of elections through research, education and public debates can contribute to local knowledge on their legal, logistical and political conditions. Yet, we recognise that it is a challenge for individual researchers to take part in these debates. Elections seldom are an impartial way to organise political competition, neither is the disciplinary knowledge on their conditions and quality always impartial. Thus, the questions: What is the profile of political science publications on electoral violence by authors from African institutions? How do African political scientists themselves perceive their potentialities and constraints in promoting utilisation of their research for electoral peace? In order to answer the first question, we used bibliometric data from Web of Science (WoS) databases to run a bibliometric analysis of political science research from African institutions. To complement the data of electoral violence publications from Kenya and Zimbabwe we extended our search on these two countries to the Sabinet African Journals database. We then did a content analysis of these articles. To address the second question, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 18 academics from Kenya and Zimbabwe stationed in universities in their respective countries.

This article proceeds as follows. First, we will describe our approach to the phenomenon of electoral violence and the changing space and role of political science in the political developments in Kenya and Zimbabwe. We will then give an overview of the volumes of political science publications output on electoral violence in Africa for the period of 1980-2019, encompassing the post-Cold War wave of democratisation. When combined with the frequency and trends of electoral violence, Kenya and Zimbabwe appear interesting and representative examples. They are among the top ten countries in the production of political science publications in Africa and they have experienced serious electoral violence, although the patterns differ. This will be followed by a summary of both countries’ scholars’ analyses and understandings of the causes of electoral violence there. We will then present the experiences and views of the scholars we have interviewed, which combined with the output and content of publications, will provide ground for a discussion on their role and impact on electoral policy. In the concluding chapter, we will discuss the factors affecting the use of political science knowledge for peaceful polling revealed by these two case studies.

Electoral violence

Electoral violence should be distinguished from wider political violence, although in practice, motivations and impacts are blurred. Mimmi Söderberg Kovacs defines it as ‘violent or coercive acts carried out for the purpose of affecting the process or results of an election’ (Söderberg Kovacs, Citation2018, p. 28). The obvious intention is to have an impact on electoral participation and procedures (Bekoe, Citation2012, p. 4) but violence can also be spontaneous and unplanned. Stephanie Burchard makes a distinction between strategic, incidental, or disruptive types of electoral violence (Burchard, Citation2015, p. 12). The government's and its supporters’ strategies to manipulate the electoral process are often manifest in pre-election violence and harassment, while post-election riots typically follow in the form of aggressive reactions among the ranks of the losing opposition (Laakso, Citation2007). The effects of violence can be many and contradictory: disruption of the elections altogether, increasing cynicism, but also, an incentive to participate in political competition (Dodo and Mpofu, Citation2019; Söderström, Citation2018, p. 870).

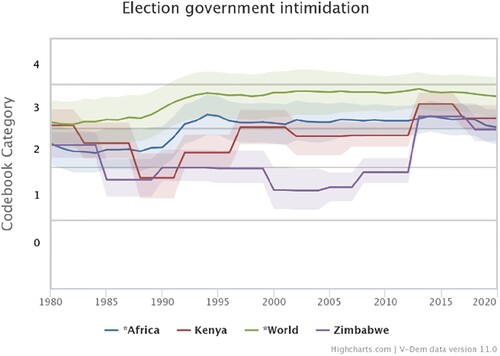

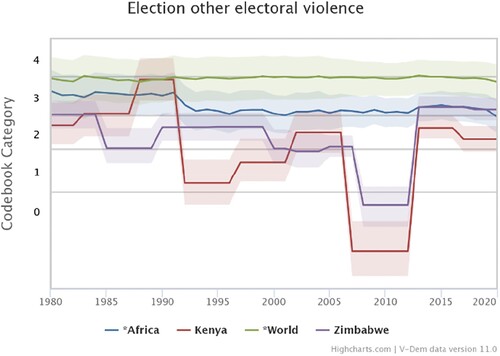

The most commonly used datasets of electoral violence, however, show consensus in the observations of the phenomenon (Birch and Muchlinski, Citation2018). and describe the trends for 1980–2020 from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) expert survey database. The first diagram shows the performance of Kenya, Zimbabwe, Africa and the world on violence instigated by the government, the ruling party, or their agents with a scale from 0 of extreme intimidation to 4 of no intimidation at all. The second one shows violence not conducted by the government, but by the opposition or non-governmental groups (Coppedge et al., Citation2020).

As the figures show, electoral violence is more frequent in Africa than the world average. The post-Cold war transition to multi-partyism seems to have reduced government instigated violence but worsened the situation as far as other electoral violence is concerned. While volatility stemming from the electoral cycles is naturally high at a country level, the wide range of values in Kenya is noteworthy. Zimbabwe, in turn, is exceptional in government intimidation, which has remained high throughout the 1990s.

In Kenya, which along with much of sub-Saharan Africa experienced a post-Cold War wave of democratisation, freedom to establish political parties was reinstalled in 1991. Elections in 1992 and again in 1997 were won by the ruling party, Kenya African National Union (KANU). Both witnessed serious violence. In 2002, the opposition won having unified into the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC). In a bid to renew a failed constitutional review process of 2001, NARC proposed a new constitution but it was rejected in 2005 (Amadi, Citation2009; Mati, Citation2012). In 2007, the widespread post-election violence lead to prosecution in the International Criminal Court (ICC) of the political rivals, Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto (Wamai, Citation2014). In the aftermath of the violence, a Grand Coalition Government was established following a mediation process. Subsequently, the constitutional reform process was revitalised (Amadi, Citation2009; Kagwanja and Southall, Citation2009) and a new constitution decentralising government power and introducing a bicameral parliament was adopted in 2010 (Zeleza, Citation2014). Using anti-ICC rhetoric, Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto joined forces to win the 2013 elections (Dancy et al., Citation2020; Ferree, Gibson, & Long, Citation2014).

Uhuru Kenyatta again won the contested 2017 elections, where the Supreme Court nullified the first round and ordered new election. Opposition leader Raila Odinga boycotted the repeat election and declared that the government was illegitimate amidst post-election violence and the government's decision to blackout all TV signals except the state broadcaster and a news channel linked to the president (Peralta, Citation2018). In 2018, however, the two reached a political compromise in what is popularly known as ‘the handshake’ (Cheeseman et al., Citation2019). Both leaders legitimised the so-called Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) that was set to make amendments to the 2010 constitution by way of a referendum (Onguny, Citation2020). Nonetheless, the High Court and Court of Appeal declared BBI unconstitutional and illegal (Wangui, Citation2021).

In Zimbabwe, in turn, freedom to form political parties was never abolished. However, since the end of the liberation struggle and fall of white-minority rule of Southern Rhodesia in 1980, the opposition parties have not been able to challenge the position of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU). The first repression of political pluralism targeted ZANU's rival nationalist party, Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), and its ethno-regional support in Matabeleland. After a series of massacres of civilians in a campaign known as Gukurahundi, ZAPU, in practice, was co-opted by the ruling party with a new ending Patriotic Front (PF) (Laakso, Citation2003). Under the leadership of Robert Mugabe ZANU-PF aimed to establish a formal one-party state, which according to the peace agreement, had become possible in 1990.

At that time, the rest of Africa was moving in the opposite direction, however. In Zimbabwe, too, civil society, students and academics among them rallied for political freedoms. A formal one-party state was never established but amidst deepening economic crisis, the government hampered the chances of the new opposition to mobilise voters beyond its urban strongholds. It supported war veterans to recruit youth for ZANU-PF's political campaigning. Trainees of the National Youth Service program, known as ‘green bombers’, attacked opposition supporters especially in the rural areas (Laakso, Citation2007). The violence and increasing pressure with electoral irregularities led the opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai to withdraw from the second round of the presidential elections. The legitimacy crisis that followed was solved with an international mediation by a formation of an inclusive government and Tsvangirai as a prime minister. But instead of genuine power-sharing and better accountability of the use of state power, the agreement turned to be another co-optation and weakening of the opposition (Welz, Citation2010).

The dominance of ZANU-PF in the Zimbabwean party system has prevailed even after the party failed to solve the succession question when the military ousted Mugabe and replaced him by former vice-president Emmerson Mnangagwa in 2018 (Tendi, Citation2020). The green bombers were active again in the subsequent presidential elections endorsing Mnangagwa's win.

Intensive power struggles and tensions, thus, have marred the party politics in Kenya and Zimbabwe. While competitive elections have been able to change the government in the former, the latter has been under the rule of the same party since 1980. In both countries, the role of the opposition has been volatile, and the legitimacy of the elections, although regularly conducted, shackled by opposition boycotts.

The evolving space of political science

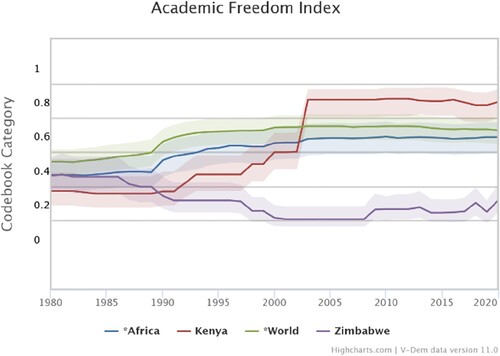

The space of political science in Kenya and Zimbabwe has evolved along the political changes. Important condition and indication of that space has been academic freedom. According to the V-Dem Academic Freedom Index, a comprehensive aggregate of expert-coded data of the respect of academic freedom, Zimbabwe in 1980 did not differ from the average African level, while the Kenyan level was clearly lower. Forty years later, the situation had become very different. Kenya had moved to a higher level than the world average. Zimbabwe, in turn, had dropped below the African average (see ).

During one-party rule, political science was suppressed in Kenya and taught only under the rubric of government and public administration. The period was marked by arbitrary closure of the University of Nairobi, expulsion of student leaders, banning of the academic staff union and detention of lecturers, political scientists included, critical of the system on grounds of ‘teaching subversion’ (Sifuna, Citation2012, p. 130). It was only after the reinstallation of multi-partyism, that political scientists were able to participate in party politics and the debates around the constitutional reforms. With the regime change of 2002 and the general liberalisation of the political environment, the space available for critical interventions and political dissidence increased further. Despite these advances, however, Daniel Sifuna (Citation2012) notes that a new set of challenges to academic freedom and university autonomy emerged. University management trends on staffing and appointments have favoured those hailing from the region where the university is located to an extent where the universities could become politically compromised and even reduced to what can be deemed ‘ethnic enclaves’ (Sifuna, Citation2012, p. 132).

In Zimbabwe, political scientists were actively involved in the consolidation of majority rule. Already in 1982, the government had established the Zimbabwe Institute of Development Studies (ZIDS) that, with the support of Dakar-based Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA), recruited not only Zimbabwean political scientists returning from exile but also scholars of other African nationalities (Raftopoulos, Citation2016). During the first decade, political economy dominated the research focus of political science while education concentrated on administration and international relations. Towards the 1990s electoral politics and party-systems started to feature on the research agenda. Harare-based Southern African Political Economy Series (SAPES) became a host for the African Association of Political Science (AAPS). In the early 1990s, the Zimbabwe branch of AAPS and the University of Zimbabwe appeared among the most vocal defenders of the multi-party system in the continent. A noteworthy example is a critical study of the conduct of the 1990 Zimbabwean general elections and public opinions: Voting for Democracy: Study of Electoral Politics in Zimbabwe by Jonathan Moyo (Citation1992), then lecturer of Political and Administrative Studies at the University of Zimbabwe.

Moyo's later career in the ruling party and government revealed the uneasy position of political scientists vis-á-vis the regime. As the Minister of Information and Publicity, he, for instance, introduced legislation restricting freedom of expression. But soon after Mugabe was overthrown, Moyo found himself opposing the regime and again criticised the conduct of the elections, including the presence of soldiers in ZANU-PF's campaigns in 2018 (Kunambura, Citation2019).

Economic decline in Zimbabwe has resulted in an exodus of skilled labour, academics included, and deteriorated the universities’ international reputation. This, notwithstanding, the government in 2021 tasked universities ‘to debate on the ideology of the second republic [led by President Emmerson Mnangagwa] as a means for, among other things, fostering political transformation in the country’ (Matenga, Citation2021).

The involvement of Kenyan and Zimbabwean political scientists in processes such as constitutional reform, power-sharing negotiations or coalition building within the ruling elite and ideology connects them immediately in what can be called high politics, i.e. ‘regime efforts to lay down procedures for decision-making and to create the mechanisms for their enforcement’ (Chazan et al., Citation1999, p. 159). For our aim to grasp their potential and actual impact, it is thus useful to examine the accounts of these scholars more in detail.

Profile of publications

In order to be versed with the volume and content of the research work of political scientists in Kenya and Zimbabwe, we conducted a search and analysis of the WoS bibliometric databases and used the InCites tool (Clarivate Analytics) filtering results by the country of the authors’ host institutions. This gave us a view of a sample of high quality research knowledge across Africa. This can be assumed to have a wider policy impact, for example through university education, which by definition should build on the highest level of scientific knowledge, as well as through top researchers’ interaction with practitioners.

As seen in , South Africa ranks, by a considerable margin, as the country with the most publications in political science and publications featuring the keywords ‘elections’ and ‘violence’ in Africa. Kenya and Zimbabwe, the countries of our interest, appear among the top seven countries. However, as many of the local publications are not recorded on WoS, we extended our search to the Sabinet African Journals database. We searched peer reviewed Social Sciences and Humanities journals with the keywords ‘elections’, ‘violence’, Kenya and Zimbabwe, and filtered the results by the period 1980-2019. With the EndNote 20 citation management software, we then distinguished articles authored or co-authored by researchers based in Kenya, Zimbabwe or South Africa. Because South Africa has attracted several political scientists from other African countries conducting research and participating in the public discussions in their countries of origin, we also included articles dealing with electoral violence in Kenya or Zimbabwe by researchers based in South Africa. Texts that were produced by researchers affiliated with an African institution in collaboration with researchers outside the continent were also included as they, too, represent accumulation of local level knowledge.

Table 1: Political science and electoral violence articles 1980–2019 by authors affiliated with African institutions, Web of Science and Incites (Clarivate Analytics).

A closer look at the articles so selected showed that many did not focus on the theme of our interest, but on its consequences, such as crisis in health care. Only about half of the articles analyzed electoral violence with an aim to understand or explain it. This gave us a sample of 49 articles for a closer content analysis. 25 articles representing research excellence on electoral violence in Kenya (20 identified from WoS and 5 from Sabinet), and 19 on Zimbabwe (5 WoS and 14 Sabinet). 5 additional articles were comparative ones looking at different African countries with either Kenya or Zimbabwe among them.

The publishers of the journals in question were in the UK, the USA, South Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Nigeria. A minority, 6, of the articles were open access. In terms of academic impact, all but 6 of the WoS articles had citations in the WoS database.

The research methods that the authors had utilised in their empirical studies were predominantly qualitative: text analysis, interviews, ethnographic observations and case studies. Sadiki Koko (Citation2013b) and Yolanda Sadie (Citation2001) utilised statistical data on electoral violence across the continent and Karuti Kanyinga and James long analyzed rounds of household public opinion data in Kenya. Of the conceptual frameworks, the most common were those paying attention to political economy, secondly to political institutions, behaviour and identities, and thirdly to peace and security. Most of the analyses were on a macro-level. Using in-depth interviews, Caroline Kihato (Citation2015) and Raftopoulos & Eppel (Citation2008) conducted micro-level analyses in their studies.

Below we present an overview of the forces that were identified as causes of electoral violence first in the articles on Kenya, then on Zimbabwe and lastly from a comparative perspective.

Kenyan approach

While several of the Kenya studies followed the theoretical perspective of political economy, most of the empirical analyses focused on particular political events and the relations between political rivals. The driving forces of electoral violence were detected within the wider socio-economic dynamics such as historical tensions of land rights, regional marginalisation and inequitable distribution of resources.

To understand the 2007–2008 violence, Sithole and Asuelime (Citation2017) combined its immediate cause – the announcement of the presidential election results amid allegations of a flawed electoral process by the opposition – and the country's historical political trends of politicisation of ethnicity and marginalisation in land ownership and control, the economy and political leadership. Samuel Kariuki (Citation2008) chronicled the history and politics of land reform from pre-independence through different presidencies, and demonstrated its tie to organised political violence, although the climate and demographic challenges according to him pointed to the need of diversifying economic processes rather than land reform. Julius Kinyeki (Citation2018), too, emphasised the land disputes as stemming from colonial rule.

The ethnicization of politics and, in particular, the use of longstanding land injustices in political mobilisation to do this, was iterated. Susan Kilonzo (Citation2009) attributed election conflict to politicised ethnicity, ethnicized politics and ethnic rivalries and clashes. Roseanne Njiru (Citation2018) asserted that the fact that land had become a symbol for ethnicity exacerbated the experience of inequalities in the distribution of power and resources. That these intertwined systemic factors were left unaddressed by the state had made them the main drivers of electoral violence. Peter Kagwanja (Citation2006), concentrated on the position of youth in electoral politics, building on the notions of youth revolution and generational identity dating back to colonial times. He demonstrated the manipulation and instrumentalization of generational and ethnic identities by the patrimonial elite. Daniel Mburu (Citation2018), in his study of the collapse of the ICC case against Ruto and Kenyatta as well as the authors of a comprehensive article on the land law reform in Kenya (Boone et al., Citation2019) stressed the limitations of legal instruments to intervene in disputes that had become ethnicized and politicised.

John Githigaro (Citation2017) advanced that the weaponization of the politics of belonging with relation to land in different parts of the country had been applied consistently in election periods since the return of multi-partyism in 1992, 1997 and 2007. The linkage between identity politics and political economy was also evident in Muhoma’s and Nyairo’s (Citation2011) depictions of the chaotic political environment created by economic turmoil. Tambe Endoh and Mbao (Citation2016) as well as Hansen and Sriram (Citation2015) stressed longer-term structural problems and cumulated frustrations due to poor living conditions and historical disenfranchisement of the voiceless majority, in addition to the real and perceived discriminations and grievances over land-issues.

Klopp and Kamungi (Citation2007) demonstrated that the concentrated presidential power and populist promises given during election campaigns made the contest for presidency a high-stakes game explaining gerrymandering and ethnic cleansing. Similarly, Mutahi and Ruteere (Citation2019) described the winner-takes-all politics of the exclusionary system that encouraged highly factionalised ethnic politics, which raised the costs of winning or losing. Ibrahim Magara (Citation2016) and Mwaura and Martinon (Citation2010) also explained gross abuse of state power by the concentration of power by the presidency, the patronage system and elite fragmentation. Wilson, Van Luik and Boit (Citation2015) also attributed the behaviour of the political elite as the main reason for the 2007–2008 post-election violence, but they concentrated on the positive role of celebrity athletes in reconciliation.

A number of publications pointed at institutional failure. Wanyama & Elklit (Citation2018) emphasised the absence of appropriate party structures behind intra-party electoral violence. Elias Opongo (Citation2010) brought to attention the lack of institutional accountability to address historical injustices. Kanyinga and Long (Citation2012) argued that the lack of prior constitutional reform contributed to the post-election violence of 2007-2008. Westen Shilaho (Citation2016) as well as Mwaura and Martinton (Citation2010) linked the divisive 2005 referendum on a draft constitution to the 2007–2008 conflict.

The subsequent institutional reforms and devolution, according to Mutahi and Ruteere (Citation2019), explain why wide-spread violence did not accompany the 2017 elections. They noted, however, that these did not prevent police brutality that stemmed from attitudes within the police force.

In their analyses, Kihato (Citation2015) and Grace Musila (Citation2009) highlighted the overtly gendered nature of political violence and how gender inequality entwined with ethnicized and socio-economic dynamics. Among emerging themes was also new technology. Mutahi and Kimari (Citation2020) addressed the role of social media in fuelling political divisions and spreading hatred. Collins Odote and Kanyinga (Citation2020) investigated the role of digital electoral technology. They argued that digital technology exacerbated rather than reduced electoral violence in contexts where electoral governance was poor and ethno-political divisions and lack of embedded democratic values prevailed.

Zimbabwean approach

All the 19 Zimbabwe articles marked electoral violence as predominantly state and ruling party sanctioned. The roles played by actors such as civil society, the media and the AU were criticised as weak in their prevention, mitigation or management of that violence.

Moyo and Ncube (Citation2015), for instance, argued that since 1980, the country, under ZANU-PF, had functioned as a militarised authoritarian regime. Additionally, Joseph Smiles (Citation2003) and Tompson Makahamadze (Citation2019) noted the repressive character of the state and, violence perpetrated by the ruling party against the opposition. Alois Mlambo's analysis of student activism showed the extension of this political violence to student protests, too (Citation2013)

Raftopoulos and Eppel analysed the use of ZANU-PF youth militia and war veterans who meted out violence on behalf of the party for promises of ‘money, maize and educational opportunities’ (Citation2008, p. 395). Dodo, Nsenduluka and Kasanda (Citation2016) explained how the liberation war legacy had been co-opted for the coordination of political violence in 2002 and 2008, with mobilisation enabled by a range of factors from poverty to forced conscription. Similarly, Mangani, Raselekoane, and Gwatimba (Citation2019) emphasised the construction of a symbiotic relationship between the party and the war veterans, and the subsequent focus on the youth to defend the regime. As an underlying dynamic enabling such tactics, James Muzondidya and Ndlovu-Gatsheni (Citation2007) analyzed the failure of the regime to address the political economy of ethnic inequalities and polarisation stemming from the colonial past.

Mwonzora and Mandikwaza (Citation2019) demonstrated that after the 2008 elections ZANU PF had shifted to manipulation strategies, using isolated violence only as a reminder of what the party could do. Closely, Solomon Muqayi (Citation2018) probed reminders of previous violence as a ZANU PF strategy to cultivate fear in the minds of the electorate in rural Zimbabwe especially. The switch to non-violent coercion was echoed in Anusa Daimon’s (Citation2016) analysis of the ZANU-PF government's opportunistic inclusion or exclusion of the migrant vote. The electoral system and the practical running of the elections were also highlighted as critical, although not the sole factors, to violence in the studies by Lloyd Sachikonye (Citation2004) and Dziva and Chigora (Citation2017), for instance.

Tendai Chari (Citation2017) demonstrated bisected ideological and political narratives in the press coverage of election violence in the state-owned and privately-owned newspapers, potentially inciting political intolerance among the public. Seda and Chivandikwa (Citation2016) on the other hand, argued that the period of political unrest between 1999 and 2008 would have been a ripe opportunity for intervention by civil society. Finally, Simon Badza (Citation2008), Khabele Matlosa (Citation2009), Patrick Dzimiri (Citation2017) and Lucky Asuelime (Citation2018) discussed the potential of SADC and the AU to support free and fair elections, but found them, over time, to have become indifferent and accommodating to ZANU PF's survival politics.

Comparisons

Kanyinga (Citation2018) posited electoral challenges engrained in winner-take-all-politics: lack of constitutionalism, a weak culture of rule of law and poor electoral governance as prime conditions for the outbreak of violence in Zimbabwe and in many other African countries as well. Constitutional and legal frameworks, in addition to structural forces such as inequitable distribution of resources, state controlled media and drawbacks in the independence of electoral commissions were identified as central by Sadie (Citation2001) who looked at the conduct of the second round of competitive multi-party elections in the whole continent since 1989.

Masunungure’s and Mutasa’s (Citation2011) overview of the performance of the governments of national unity in Zimbabwe and Kenya, with a reference to Côte d’Ivoire, too, stressed the short term character of these arrangements with regard to the enduring structural problems. Koko (Citation2013a) comparing the cases of Rwanda, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Kenya, argued that power sharing, which was used to address political violence based on ethnic divisions, actually weakened the prospects of justice and human rights protection. Elsewhere, in a comprehensive overview of literature and data across the continent, Koko (Citation2013b) asserted the importance of understanding the complexity of the causes of election violence in different countries but emphasised the lessons learned from the engagement of a wide spectrum of stakeholders in its prevention.

As a summary of the research presented above, we can note that historical experiences of inequalities and the intensity of political competition appeared as important root causes for electoral violence in Kenya, Zimbabwe and elsewhere in Africa. The politicised nature of these factors effectively hampered African or international multilateral interventions to mitigate or solve the tensions. The ruling regimes exerted power not only within their countries but rallied political support even from outside. Thus the reserved mediation by the SADC and the AU in Zimbabwe and the failed ICC criminal cases in Kenya.

Most of the studies on Kenya's electoral violence pointed to the interconnectivity of the causes of electoral violence; land and other socio-economic injustices tied to ethnicized politics and vice versa. While the issues raised were more often than not traced to the country's colonial and early post-colonial history, the researchers also recognised the impact of institutional reforms, organisation of the political parties and state policies with regard to factionalised ethnic politics. In the case of Zimbabwe, electoral violence was understood as stemming from the character of the state's, ZANU-PF's, strategy. In a way, violence as well as all other election manipulation tactics reflected the threat the opposition and its potential popularity was posing to the regime.

Perceptions of political scientists on their influence

The experiences of political scientists in Kenya and Zimbabwe shed further light on the role of scholarship on electoral politics. We recorded the views of 18 scholars (9 in Zimbabwe and 9 in Kenya) between June 2019 and October 2021 of their interaction with decision-making and the public, and their perceptions of their influence. The interviewees were working at the main public universities. We identified them by their profiles in their universities’ web pages and by a snowball method. Our target group was not only researchers who themselves had conducted research on elections or political violence, but researchers and teachers of political science in general covering different theoretical, methodological and empirical orientations (see Laitin, Citation1998) and thus having a broad view of the discipline's relevance and impact – similar to the range of approaches reviewed in the electoral violence studies above. The group was diversified, including senior scholars and emerging ones with experiences in different universities including those abroad. However, only 4 were women reflecting the patriarchal structures of the academic environment in much of Africa.

The semi-structured interview method served the purpose of letting the interviewees speak in their own words, reflecting their subjective perceptions. The questions covered the following: freedom to teach and do research, ability to express views on political issues and societal relevance of university education. We also asked if scholars were able to, or had been invited to, advise the government, civil society, political parties or international development agencies working in the field of democratisation. Transcripts of the interviews were coded by NVivo software along references to elections, political violence and party competition among others. We identified the themes as they emerged from these references rather than in accordance to pre-determined questions (Saunders et al., Citation2018). All the interviews were anonymized and all the interviewees allowed the interviews to be recorded.

Below we describe the meanings connected to these themes (for the method see Alasuutari, Citation1995; Silverman, Citation2009). First, the perceptions of the scholars of the public respect of universities and academic qualifications, which can be seen as essential for the value given to scientific knowledge and expert opinions. Then what the scholars identified as the specific constraints for political science knowledge to enhance electoral peace.

Respect and utilisation of academic knowledge

Our interviewees in both countries testified about the appreciation of university education. According to a professor in Zimbabwe, ‘if you have a bachelor's you must get a master's degree, and if you have master's you want to get a doctorate.’ The governments emphasised qualifications in recruitments and sometimes offered special university programs for employees. This implied a direct link for the faculty to government authorities, including bodies responsible for the running of the elections. ‘We have, actually, direct access. You can pick up a phone and talk to somebody that you know directly,’ one of the scholars we interviewed stated. For example, the chairperson of the Zimbabwe electoral commission was ‘a product of our department’, a professor there noted. A Kenyan professor, in turn, told about a colleague who had served as the vice-chairman of a commission investigating solutions to political violence after the 2017 elections.

The scholars felt that they were free to express their opinions of the quality of elections, including criticism of the political parties. In Kenya, for instance, we learned about a PhD thesis that had focused on the irregularities of the presidential elections. There were, however, also sensitive issues that had proved difficult to study and, at least potentially, suggested a tendency of self-censorship. The ICC case of the 2007 post-election violence was mentioned as an example.

A general perception among the scholars was that the problem of electoral violence was well known and discussed in public. Thanks to private media, Zimbabweans knew about the green bombers, for instance. As stated by one respondent, there was ‘a lot of public outcry’ that the government should do away with them. The Kenyan interviewees stressed that election-related debate, including the issues of intimidation and violence, was common and popular in traditional media; TV appearances and newspaper commentaries.

Political parties also used academics in their campaigns: ‘everybody is trying to look for scholars to be in their team so that they can write their manifestos. Some of them are being kept as advisors, some of them are being kept as resource persons’, in the words of one professor.

However, as far as the immediate impact to mitigate electoral violence was concerned, a Kenyan professor noted: ‘the products of our research are not for the ordinary persons, those who get involved in electoral violence. They are simply instigated by the politicians. They are not those who would get to read of what we have researched on.’ Civic education programmes, where the scholars worked together with NGOs as facilitators or consultants, on the other hand, were targeting the whole electorate. These mostly ran just ahead of elections with funding coming from development partners, although, according to one of our interviewees they ought to be an ongoing activity.

In Zimbabwe, while direct influence on the electoral policies of the government was difficult, the regional organisation, SADC had provided one channel through which the scholars had been able to make a contribution. SADC's involvement had been critical for the formation of an inclusive government after the violent 2008 presidential elections, for instance. Zimbabwean political scientists had served in SADC's Electoral Advisory Council (SEAC) and participated in the drafting of its Principles and Guidelines Governing Democratic Elections covering the whole electoral cycle. Significantly, the scholars had been nominated as experts, not as representatives of their governments. One of them told us ‘I have never asked our foreign ministry what I should do. I never reported to them what I have done.’

Ethnic divisions in Kenya

Ethnic tensions, which were identified as major drivers of electoral violence in Kenya, were seen as affecting also the abilities of scholars to make a contribution there. One professor characterised the elections as ‘very messy affairs. For everyone on one side, there will be another one on the other side, even if they are coming from the same department’. The professor continued: ‘If you are a professor from some region, and the kingpin from that region needs people in government, you may become one of the people that find support from this kingpin, are given resources, so that you can continue upholding the structure.’ We were even told about a scholar who had worked for the opposition and charged of inciting violence after the 2017 general elections.

The changing coalitions and power sharing in the government resonated among the academics as ‘flipflopping about one side of the divide or the other’, as expressed by a lecturer. One of our interviewees added that even appointments at universities were contingent upon ethnic affiliation: ‘The political overflows into the academic.’ Notably, it was mainly the regional universities that were seen to be highly ethnicized. Yet there were also scholars, who as ‘public intellectuals’, were able to speak about their empirical research on political participation, present data and evidence of opinion polls, for instance, without being labelled as partial.

Economic crisis in Zimbabwe

Concerning the constraints on the scholars’ influence on electoral politics, in the Zimbabwean dominant party system the main issues related to education and economic conditions. Low levels of education, even among the politicians, was identified as one of the main limitations. ‘Those who go to the parliament are party people. They are not well educated’, said a professor. This observation further pointed to the sway of the countryside. One of the respondents explained: ‘the people in the urban areas who vote for the opposition are not a critical mass. For the rural areas it's not really issues-based concerns like human rights. The critical mass are those who are poor. They are controlled by the ruling party. The elections are held on issues like food aid.’ Even though the food aid came from international sources, the ZANU-PF government delivered it, not the opposition.

Our interviewees saw the ‘economic imperative’ frustrating the influence of evidence-based knowledge too, because it fuelled corruption: ‘inefficiencies and misallocation of resources increase.’ Furthermore, effects of the economic decline; the hyperinflation eroding government salaries and the breakdown of infrastructure, such as water and electricity shortages, affected the working conditions in universities. That explained why political scientists were less active in political life than before. ‘Priorities for many are survival, it is a daily struggle’, one senior scholar observed. Independent think tanks that had nurtured critical research and debates were still active, but according to our interviewees, their ability to interact with the government and to be heard by the public was no longer the same as it had been in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Although scholars in both countries felt that they were free to participate in political discussions and were able to disseminate evidence-based knowledge on electoral politics, they also identified important constraints to have significant effects on the behaviour of the government or political parties and most importantly through them to the political mobilisation of the wide electorate. In Zimbabwe, these were connected to the economic imperative in particular, frustrating the academia and civil society. In Kenya, to the politicised ethnicity spilling over to universities, too.

Conclusions

Our overview of the Kenyan and Zimbabwean political science publications output on electoral violence showed an ample knowledge base on the topic in both countries. Researchers had approached it with empirical analysis on individual elections, local and national level, focusing on the implications and the underlying societal and economic tensions and injustices.

In Kenya, the ethnicization of politics and the colonial legacy of land distribution were among the most referred root causes. Researchers also identified institutional factors related to the organisation of the parties, constitution, and governance. Winner-takes-all competition, the concentration of powers to the executive and populist mobilisation of voters exemplified dynamics where relatively targeted evidence-based policy interventions could enhance peaceful polling.

The state's abuse of power, instigation of violence and manipulation of vulnerable population in order to secure electoral victories was clearly proved from the Zimbabwean sample. The studies also revealed how the legacy of the liberation war, in the mobilisation of war veterans and after them the youth for violent campaigning, facilitated the stronghold of ZANU-PF.

Semi-structured interviews with political scientists in both countries showed that they had connections as advisers, critics and supporters to different stakeholders: government, political parties, media and civil society. And that they enjoyed freedom to express criticism, which had not always been the case. But the interviews also revealed structural obstacles hampering the ability of the faculty to reach its fullest potential to enhance the quality of election.

The scholars had opportunities to influence the behaviour of the electorate particularly through their involvement in the work of the NGOs and media appearance. Interaction with political parties and regional organisations appeared important, too. The political scientists we interviewed felt they could openly be critical and address publicly similar themes as those identified in the electoral studies we reviewed. However, (self)censorship was an issue at least to the extent it related to the ethnicization of political power and clientelism in the faculty itself. Furthermore, the public and media attention to electoral violence was limited predominantly to the campaign periods and there remained a distance between the scholars and the average voters who were the main target of party mobilisation.

In this regard, the experiences of the professors and lecturers on the role of private and government controlled media and social media deserves to be looked more in detail. For a better understanding of the research output, future research should also trace and analyze research output beyond peer reviewed journal articles to commissioned reports and material used in civic education.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Elina Oinas and the participants of the 6th joint Nordic Development Research Conference, working group ‘Academic scholarship that matters? Matters where?’ for comments, as well as Mimmi Söderberg Kovacs and the participants of the Folke Bernadotte Academy Research Workshop, ‘The Pursuit of Peaceful Polling’ (December, 2020), where the first findings from the Zimbabwe case study were presented. We want to thank the anonymous reviewer for insightful suggestions and Tiina Kontinen and Ilona Steiler for editorial advice and comments that helped us to improve our argumentation. We are grateful to Florian Stoll for the conduction of interviews in Kenya, Michael Chukwuebuka Igbokwe for interview transcriptions and Anna Mattsson for research assistance. Our deepest gratitude goes to the scholars, who devoted their time to our study. Nordic Africa Institute and Tampere University supported our work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Liisa Laakso

Liisa Laakso is an expert on world politics and international development cooperation. Her research interests include political science, African studies, democratisation of Africa, world politics, crisis management, foreign policy, EU-Africa policy and the global role of the European Union.

Esther Kariuki

Esther Kariuki is a MSc. graduate in International Development and Management from Lund University. Her research interests lie within international development, particularly in sub Saharan Africa: education, urban livelihoods, politics and democratisation.

References

- Alasuutari, P., 1995, Researching Culture: Qualitative Method and Cultural Studies, London: Sage.

- Amadi, H., 2009, ‘Kenya’s Grand Coalition Government - another obstacle to urgent constitutional reform?’, Africa Spectrum, Vol. 44, No. 3, pp. 149–164.

- Asuelime, L. E., 2018, ‘The African Union and election related violence in Zimbabwe’, Gender & Behaviour, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 11790–11804.

- Badza, S., 2008, ‘Zimbabwe’s 2008 elections and their implications for Africa’, African Security Review, Vol. 17, No. 4, pp. 2–16.

- Bandola-Gill, J., M. Flinders and A. Anderson, 2021, ‘Co-option, control and criticality: The politics of relevance regimes for the future of political Science’, European Political Science, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 218–236.

- Barongo, Y. R. (ed), 1983, Political Science in Africa: A Critical Review, London: Zed Books.

- Bekoe, D. A. O., 2012, ‘Introduction, scope, nature, and pattern of electoral violence in Sub-Saharan Africa’, in D. A. O Bekoe, ed, Voting in Fear: Electoral Violence in Sub-Saharan Africa, Washington, D.C: United States Institute of Peace Press, pp. 1–14.

- Berndtson, E., 1991, ‘The development of political science: methodological problems of comparative research’, in D. Easton, J. Gunnell and L Graziano, eds, The Development of Political Science: A Comparative Survey, London: Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 34–58.

- Birch, S. and D. Muchlinski, 2018, ‘Electoral violence prevention: what works?’, Democratization, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 385–403.

- Boone, C., A. Dyzenhaus, A. Manji, C. W. Gateri, S. Ouma, J. K. Owino, A. Gargule and J. M. Klopp, 2019, ‘Land law reform in Kenya: Devolution, veto players, and the limits of an institutional Fix’, African Affairs, Vol. 118, No. 471, pp. 215–237.

- Burchard, S. M., 2015, Electoral Violence in Sub-Saharan Africa: Causes and Consequences, Boulder: FirstForumPress, A Division of Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc.

- Chari, T. J., 2017, ‘Electoral violence and its instrumental logic: Mapping press discourse on electoral violence during parliamentary and presidential elections in Zimbabwe’, Journal of African Elections, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 72–96.

- Chazan, N., P. Lewis, R. Mortimer, D. Rothchild and S. J. Stedman, 1999, ‘High politics: The procedures and practices of government’, in N. Chazan, P. Lewis, R. Mortimer, D. Rothchild and S. J. Stedman, eds, Politics and Society in Contemporary Africa, London: Macmillan Education UK, pp. 159–195.

- Cheeseman, N., K. Kanyinga, G. Lynch, M. Ruteere and J. Willis, 2019, ‘Kenya’s 2017 elections: Winner-takes-all politics as usual?’, Journal of Eastern African Studies, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 215–234.

- Coppedge, M., J. Gerring, C. H. Knutsen, S. I. Lindberg, J. Teorell, D. Altman, M. Bernhard, et al., 2020, V-Dem Dataset 2020.

- Daimon, A., 2016, ‘ZANU (PF)’s manipulation of the “Alien” vote in Zimbabwean elections: 1980–2013’, South African Historical Journal, Vol. 68, No. 1, pp. 112–131.

- Dancy, G., Y. M. Dutton, T. Alleblas and E. Aloyo, 2020, ‘What determines perceptions of bias toward the International Criminal Court? Evidence from Kenya’, Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 64, No. 7–8, pp. 1443–1469.

- Dodo, O. and B. Mpofu, 2019, Female Political Youth Activism. A Study of the Motivation in Seke.

- Dodo, O., E. Nsenduluka and S. Kasanda, 2016, ‘Political bases as the epicenter of violence: cases of Mazowe and Shamva, Zimbabwe’, Journal of Applied Security Research, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 208–219.

- Dzimiri, P., 2017, ‘African multilateral responses to the crisis in Zimbabwe: A responsibility to protect Perspective’, Strategic Review for Southern Africa, Vol. 39, No. 2, pp. 50–77.

- Dziva, C. and P. Chigora, 2017, ‘Building a case for the adoption of an E-voting electoral system in Zimbabwe based on the Namibian Experience’, Journal of Public Administration and Development Alternatives (JPADA), Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 47–61.

- Ferree, K. E., C. C. Gibson and J. D. Long, 2014, ‘Voting behavior and electoral irregularities in Kenya’s 2013 Election’, Journal of Eastern African Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 153–172.

- Githigaro, J. M., 2017, ‘Politics of belonging - exploring land contestations and conflicts in Kenya’s North Rift Region’, Africa Insight, Vol. 46, No. 4, pp. 83–95.

- Hansen, T. O. and C. L. Sriram, 2015, ‘Fighting for justice (and survival): Kenyan civil society accountability strategies and their Enemies’, International Journal of Transitional Justice, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 407–427.

- Ibrahim, J., 1998, ‘Political scientists and the subversion of democracy in Nigeria’, in G. Nzongola-Ntalaja and M. C Lee, ed, The State and Democracy in Africa, Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, pp. 114–124.

- Kagwanja, P. M., 2006, ‘“Power to Uhuru”: youth identity and generational politics in Kenya’s 2002 Elections’, African Affairs, Vol. 105, No. 418, pp. 51–75.

- Kagwanja, P. and R. Southall, 2009, ‘Introduction: Kenya – A democracy in retreat?’, Journal of Contemporary African Studies, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 259–277.

- Kanyinga, K., 2018, ‘Elections without constitutionalism: votes, violence, and democracy gaps in Africa’, African Journal of Democracy and Governance, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 147–168.

- Kanyinga, K. and J. D. Long, 2012, ‘The political economy of reforms in Kenya: The post-2007 election violence and a new constitution’, African Studies Review, Vol. 55, No. 1, pp. 31–51.

- Kariuki, S., 2008, ‘“We’ve been to hell and back … ” can a botched land reform programme explain Kenya’s political crisis? (1963–2008)’, Journal of African Elections, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 135–172.

- Kihato, C. W., 2015, ‘“Go back and tell them who the real men are!” gendering our understanding of kibera’s post-election Violence’, International Journal of Conflict and Violence, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 13–24.

- Kilonzo, S., 2009, ‘Ethnic minorities wedged up in post-election violence in Kenya: A lesson for African Governments’, Critical Arts, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 245–251.

- Kinyeki, J., 2018, ‘Community resilience and social capital in the reconstruction and recovery process for post-election violence victims in Kenya’, African Journal on Conflict Resolution, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 115–144.

- Klopp, J. and P. Kamungi, 2007, ‘Violence and elections: will Kenya collapse?’, World Policy Journal, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 11–18.

- Koko, S., 2013a, ‘The tensions between power sharing, justice and human rights in Africa’s “post-violence” societies: Rwanda, Kenya and the Democratic Republic of the Congo’, African Human Rights Law Journal, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 254–280.

- Koko, S., 2013b, ‘Understanding election-related violence in Africa - Patterns, causes, consequences and a framework for preventive Action’, Journal of African Elections, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 51–88.

- Kunambura, A., 2019, ‘Poll Ghost Haunts President’, Zimbabwe Independent, 23 August 2019.

- Laakso, L., 2003, ‘Opposition politics in independent Zimbabwe’, African Studies Quarterly, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 119–137.

- Laakso, L., 2007, Insights into electoral violence in Africa, in M. Basedau, G. Erdmann and A. Mehler eds, Votes, Money and Violence: Political Parties and Elections in Africa, Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, pp. 224–252.

- Laitin, D. D., 1998, ‘Toward a political science discipline: authority patterns Revisited’, Comparative Political Studies, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 423–443.

- Magara, I., 2016, ‘Transitional justice and democratisation nexus: challenges of confronting legacies of past injustices and promoting reconciliation within weak institutions in Kenya’, African Journal on Conflict Resolution, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 9–34.

- Makahamadze, T., 2019, ‘The role of political parties in peacebuilding following disputed elections in Africa - The case of Zimbabwe’, Africa Insight, Vol. 49, No. 3, pp. 142–158.

- Mangani, D. Y., N. R. Raselekoane and L. Gwatimba, 2019, ‘Prospects for the future role of Ex-combatants in the Zimbabwean nationalist politics or is it the end of the era?’, Gender and Behaviour, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 1390–13919.

- Masunungure, E. V. and F. Mutasa, 2011, ‘The nexus between disputed elections and Governments of National Unity in Africa’, Africa Insight, Vol. 41, No. 1, pp. 129–142.

- Matenga, M., 2021, ‘Varsities Ordered to Strategise for ED’, NewsDay, 1 October 2021.

- Mati, J. M., 2012, ‘Social movements and socio-political change in Africa: The ufungamano initiative and Kenyan constitutional reform struggles (1999–2005)’, VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 63–84.

- Matlosa, K., 2009, ‘The role of the Southern African development community in the management of Zimbabwe’s post-election crisis’, Journal of African Elections, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 46–73.

- Mazrui, A. A., 1975, ‘Academic freedom in Africa: The dual Tyranny’, African Affairs, Vol. 74, No. 297, pp. 393–400.

- Mburu, D. M., 2018, ‘The lost Kenyan duel: The role of politics in the collapse of the International Criminal Court cases against Ruto and Kenyatta’, International Criminal Law Review, Vol. 18, No. 6, pp. 1015–1047.

- Mlambo, A. S., 2013, ‘Student activism in a time of crisis - Zimbabwe 2000–2010: A tentative Exploration’, Journal for Contemporary History, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 184–204.

- Moyo, J. N., 1992, Voting for Democracy: A Study of Electoral Politics in Zimbabwe, Harare: University of Zimbabwe Publications.

- Moyo, G. and C. Ncube, 2015, ‘The Tyranny of the executive-military alliance and competitive authoritarianism in Zimbabwe’, AFFRIKA: Journal of Politics, Economics and Society, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 2015–2052.

- Muhoma, C. and J. Nyairo, 2011, ‘Inscribing memory, healing a nation: post-election violence and the search for truth and justice in Kenya Burning’, Journal of Eastern African Studies, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 411–426.

- Muqayi, S., 2018, ‘The strategies applied by the Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) to dominate the 2013 harmonised elections in Zimbabwe’, Journal of African Foreign Affairs, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 45–64.

- Musila, G. A., 2009, ‘Phallocracies and gynocratic transgressions gender, state power and Kenyan public Life’, Africa Insight, Vol. 39, No. 1, pp. 39–57.

- Mustapha, A. R., 2006, ‘Rethinking Africanist political science’, CODESRIA Bulletin, No. 3-4, pp. 3–10.

- Mutahi, P. and B. Kimari, 2020, ‘Fake news and the 2017 Kenyan Elections’, Communicatio, Vol. 46, No. 4, pp. 31–49.

- Mutahi, P. and M. Ruteere, 2019, ‘Violence, security and the policing of Kenya’s 2017 Elections’, Journal of Eastern African Studies, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 253–271.

- Muzondidya, J. and Sabelo J Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2007, ‘Echoing silences’: ethnicity in Post-Colonial Zimbabwe, 1980–2007’, African Journal on Conflict Resolution, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 275–297.

- Mwaura, P. N. and C. M. Martinon, 2010, ‘Political violence in Kenya and local churches’ responses: The case of the 2007 post-election Crisis’, The Review of Faith & International Affairs, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 39–46.

- Mwonzora, G. and E. Mandikwaza, 2019, ‘The menu of electoral manipulation in Zimbabwe: food handouts, violence, memory, and fear – case of Mwenezi East and Bikita West 2017 by-Elections’, Journal of Asian and African Studies, Vol. 54, No. 8, pp. 1128–1144.

- Njiru, R., 2018, ‘Outsiders in their own nation: electoral violence and politics of “internal” displacement in Kenya’, Current Sociology, Vol. 66, No. 2, pp. 226–240.

- Odote, C. and K. Kanyinga, 2020, ‘Election technology, disputes, and political violence in Kenya’, Journal of Asian and African Studies, Vol. 56, No. 3, pp. 558–571.

- Onguny, P., 2020, ‘The politics behind Kenya’s Building Bridges Initiative (BBI): Vindu Vichenjanga or sound and fury, signifying nothing?’, Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue Canadienne des études Africaines, Vol. 54, No. 3, pp. 557–576.

- Opongo, E. O., 2010, ‘Kenyan challenges for a prophetic and vigilant Church’, The Review of Faith & International Affairs, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 77–79.

- Oyugi, W.O. (ed), 1989, The Teaching and Research of Political Science in Eastern Africa, Addis Ababa: Organization for Social Science Research in Eastern Africa.

- Peralta, E., 2018, ‘As Government Ignores Court Order, Kenya’s Media Blackout Continues’, NPR, 2 February 2018.

- Raftopoulos, B., 2016, ‘Zimbabwe institute of development studies (ZIDS): The early context of Sam Moyo’s Intellectual Development’, Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 5, No. 2–3, pp. 187–201.

- Raftopoulos, B. and S. Eppel, 2008, ‘Desperately seeking sanity: What prospects for a new beginning in Zimbabwe?’, Journal of Eastern African Studies, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 369–400.

- Sachikonye, L. M., 2004, ‘Zimbabwe: Constitutionalism, the electoral system and challenges for governance and Stability’, Journal of African Elections, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 140–159.

- Sadie, Y., 2001, ‘Second Elections in Africa: An Overview’, Politeia, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 63–86.

- Saunders, B., J. Sim, T. Kingstone, S. Baker, J. Waterfield, B. Bartlam, H. Burroughs and C. Jinks, 2018, ‘Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and Operationalization’, Quality & Quantity, Vol. 52, No. 4, pp. 1893–1907.

- Seda, O. and N. Chivandikwa, 2016, ‘Civil society, religion and applied theatre in a kairotic moment –preliminary reflections on a project on political violence and torture in Zimbabwe, 2001–2002’, Commonwealth Youth and Development, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 81–91.

- Shilaho, W. K., 2016, ‘The paradox of Kenya’s constitutional reform process: what future for constitutionalism?’, Journal for Contemporary History, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 184–207.

- Sifuna, D. N., 2012, ‘Leadership in Kenyan public universities and the challenges of autonomy and academic freedom: An overview of trends since Independence’, Journal of Higher Education in Africa/Revue de L’enseignement Supérieur en Afrique, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 121–137.

- Silverman, D., 2009, Doing Qualitative Research, Third Edition, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Sithole, T. and L. E. Asuelime, 2017, ‘The role of the African Union in post-election violence in Kenya’, African Journal of Governance and Development, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 98–122.

- Smiles, J., 2003, ‘Zimbabwe: Review of the 2002-Presidential Election’, Journal for Contemporary History, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 152–164.

- Söderberg Kovacs, M., 2018, ‘Introduction: The everyday politics of electoral violence in Africa’, in J. Bjarnesen and M Söderberg Kovacs, eds, Violence in African Elections: Between Democracy and Big Man Politics, London: Zed Books, pp. 21–59.

- Söderström, J., 2018, ‘Fear of electoral violence and its impact on political knowledge in Sub-Saharan Africa’, Political Studies, Vol. 66, No. 4, pp. 869–886.

- Stoker, G., G. B. Peters and J. Pierre, 2015, ‘Introduction’, in G. Stoker, G. B. Peters and J Pierre, ed, The Relevance of Political Science, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–16.

- Tambe Endoh, F. T. and M. M. and Mbao, 2016, ‘Political Dynamics in Kenya’s Post-Electoral Violence: Justice without Peace or Political Compromise’, p. 14.

- Tendi, B.-M., 2020, ‘The motivations and dynamics of Zimbabwe’s 2017 Military Coup’, African Affairs, Vol. 119, No. 474, pp. 39–67.

- Wamai, N. E., 2014, ‘Mediating Kenya’s post-election violence: from a peace-making to a constitutional moment’, in G. R. Murunga, A. Sjögren and D. Okello eds, Kenya: The Struggle for a New Constitutional Order, London: Zed Books, pp. 66–78.

- Wangui, J., 2021, Appellate Court Upholds Ruling against BBI, Business Daily. https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/economy/appeal-court-upholds-ruling-against-bbi-3519108.

- Wanyama, F. O. and J. Elklit, 2018, ‘Electoral violence during party primaries in Kenya’, Democratization, Vol. 25, No. 6, pp. 1016–1032.

- Welz, M., 2010, ‘Zimbabwe’s “inclusive government”: Some observations on its first 100 Days’, The Round Table, Vol. 99, No. 411, pp. 605–619.

- Wilson, B., N. Van Luijk and M. K. Boit, 2015, ‘When celebrity athletes are “Social Movement Entrepreneurs”: A study of the role of Elite runners in run-for-peace events in post-conflict Kenya in 2008’, International Review for the Sociology of Sport, Vol. 50, No. 8, pp. 929–957.

- Zeleza, P. T., 2014, ‘The protracted transition to the second republic in Kenya’, in G. R. Murunga, A. Sjögren and D Okello eds, Kenya: The Struggle for a new Constitutional Order, London: Zed Books, pp. 17–43.