Abstract

In contrast to its Nordic neighbours, Finland has failed to fulfil the 0.7 per cent of GNI target for development assistance over the past three decades. This has been the case despite restated commitments ‘to reach 0.7’ by every government since 1993 and Finland’s otherwise progressive role as a Nordic donor. This inconsistency, but also the Finnish aid approach in general, has been charted by only a few academic contributions. In this article, we begin by revisiting the Finnish aid paradigm for background purposes and identify continuities and changes including degrees of change [Hall, P., 1993, ‘Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: The case of economic policymaking in Britain’, Comparative Politics, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 275–296] since the early 1990s. Then we shift our focus to the 0.7 target in the context of domestic political forces [Lancaster, C., 2007, Foreign Aid: Diplomacy, Development, Domestic Politics, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press] that shape Finnish aid. In addition, we provide snapshots of the two most significant changes in Finnish aid that relate to aid volume (centred in 1991 and 2015) and address them through the conceptual lenses of de/politicisation [Wood, M., 2015, ‘Puzzling and powering in policy paradigm shifts: politicisation, depoliticisation and social learning’, Critical Policy Studies, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 2–21]. We conclude that some strong underlying continuities can be identified in the Finnish aid paradigm (1993–2021) concerning particularly poverty reduction, the role of aid, foreign and commercial policy self-interests as well as global concerns. The aspirations to reach the 0.7 per cent target are also a part of this continuum. However, domestic political forces related to the Finnish government coalitions and budgetary politics hinder the fulfilment of the self-declared 0.7 target. Furthermore, the largely depoliticised nature of both aid and these dynamics make it difficult to change the course towards true commitment.

Finnish development aid in the nordic context: ‘the odd man out’ to be understood

Finland has had an official development policy for almost 30 years, its background rooted in the formation of the country’s external role (Koponen and Siitonen, Citation2005; Siitonen, Citation2005; Citation2011; for earlier see Antola, Citation1978).Footnote1 In practical terms, the main task of development policy is to guide development aid, its purpose, volume, and selection of beneficiaries through different channels and instruments.Footnote2 In this article, these aspects are seen as the core elements that manifest the Finnish aid paradigm – the ideational framework underlying aid at any given time. As Koponen and Siitonen (Citation2005, p. 15) noted more than 15 years ago, the evolution of Finnish aid has been far from linear, but there have been some underlying continuities. Since their last comprehensive review in 2005, these have not been thoroughly explored.

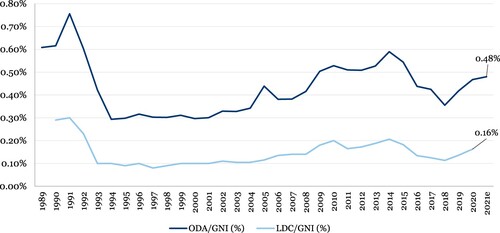

One of the most prominent of these continuities is that in conspicuous and persistent contrast to its Nordic neighbours, Finland has failed to fulfil the 0.7 per cent of GNI target for official development assistance (ODA) during the past three decades. This has been the case despite the stated commitment ‘to reach 0.7’ by the highest levels of every government irrespective of the political parties in power or the state of the Finnish economy. In fact, the commitment that Finland made for the first time at the UN General Assembly in 1970 was reached only once (0.76 per cent of GNI), in 1991, and even then it was facilitated by a sharp economic downturn, which lowered the country’s GNI drastically before the aid volume was cut. Since then, Finland’s aid disbursements have fluctuated between 0.29 and 0.59 per cent of GNI, with an average of 0.42 per cent. The almost ritualistic striving for the 0.7 target and changes in volume suggest that Finland has not been able to secure the material base for its aid, which Stokke (Citation2019, p. 8), for example, sees in most cases as the most important part of the policy. Essentially, the volume of aid enables or constrains the achievement of set goals or the use of different aid instruments.

The failure to fulfil the 0.7 target has made Finland the ‘odd man out’ as Elgström and Delputte (Citation2015, p. 30) describe it in the context of the Nordic countries. It also stands in contradiction with Finland’s external and internal image of an otherwise progressive donor and like-minded partner on the international scene (Elgström Citation2017; Elgström and Delputte, Citation2015; Siitonen, Citation2011). The renewed commitments to 0.7 as an active EU and OECD DAC member or as an ambitious promoter of both Agenda2030 and financing for sustainable development have not changed the case (Europe Sustainable Development Report, Citation2021). Nevertheless, Finland’s claims to Nordic donor identity have remained central to Finnish aid debates and in official development policies (see especially MFA, Citation2021).

In this article, our aim is to explain this inconsistency more closely and in doing so focus on the domestic policy arena, where domestic politics and international influences meet. To put the 0.7 target in context, we first outline the conceptual basis for this contribution (second section). We then briefly revisit as a background the Finnish aid paradigm and its evolution (third section). In particular we ask, what has characterised the Finnish aid paradigm, especially the perceived purpose(s) of aid and its material base, since the first government-level development policy in 1993? What continuities and what kind of changes (including degrees of change, Hall, Citation1993) can be identified? Then we shift our focus to the 0.7 target in the context of domestic political forces (Lancaster, Citation2007) that shape Finnish aid. We also provide snapshots of the two most significant changes in Finnish aid that relate to aid volume (centred in 1991 and 2015) through the conceptual lenses of de/politicisation (Wood, Citation2015) (fourth section). Finally, fifth section presents our conclusions and suggestions for further research.

Analysing the Finnish aid paradigm: the conceptual basis

Paradigm change (or continuity)

In our overview of the Finnish aid paradigm, we refer to the concept of policy paradigm as originally developed by Peter Hall in his seminal article (Citation1993) on British domestic economic policy-making. In Hall’s view, paradigms are in effect world-views on a given policy-area. They not only prescribe certain policies, or preferred policy-instruments within them. Paradigms also offer the very view of the issues in the policy-area itself, describing both existing problems and possible solutions, and therefore the kinds of objectives that would be suitable in that presentation of the context (Hall, Citation1993, p. 273). Following approximately in Hall’s footsteps, we understand ‘paradigm’ broadly as a set of ideas concerning how the world works in a given policy area. It can also be seen as ‘an instruction manual’, for understanding what ‘causal’ mechanisms are believed to exist there for pursuing (selected) goals.

In Hall’s view, the main avenue for paradigm-change is through social learning (Hall, Citation1993, p. 276). Or, in other term he uses, ‘puzzling’ (Hall, Citation1993, p.275), meaning pondering collectively and figuring out what the appropriate goals for a given policy area are and how to best achieve them, especially among decision-makers. More specifically for Hall, much of the social learning happens through experimentation. Hall sees this social learning taking place in three possible steps, or ‘degrees’, each more ‘radical’ than the one before. In Hall’s ‘first order change’, merely the parameters of existing instruments are adjusted (Hall, Citation1993, p. 280). In his ‘second order change’, altogether different means or instruments are put to use, even though the ends themselves remain broadly the same. The first two orders of change Hall sees as part of ‘normal’ everyday policy-making, where the existing instruments used are constantly adjusted, or even switched. But in the third most ‘radical’ step, even the whole world-view of what the given policy-area is about is changed, leading into entirely different perceptions of the issues to be addressed (Hall, Citation1993, p. 279). This last step usually only occurs, according to Hall, if there is sufficient cumulative evidence of real or perceived ‘policy failure’.

In our overview of Finnish aid paradigm and its continuities and changes, we claim that key worldviews, or, to use Hall’s term, paradigms, can be inferred from the development policy documents of the time as they are the officially declared intentions and guidelines of the government for itself – and for voters and citizens holding it to account. In some (extended) sense they can be considered as analogous to ‘legal’ documents. These documents explain and justify the key ideas, the purpose of aid and define the channels and instruments through which aid is to be allocated to beneficiaries. In the Finnish case, the aid paradigm is most clearly manifested in the official development policy programmes (usually in a form of the government reports or White Papers). As there is no comprehensive law or Act of Parliament on aid, these overarching policy documents represent the official view by each government.

Politicisation/depoliticisation (of aid)

Wood’s (Citation2015, p. 2) work on the politicisation/depoliticisation of the processes in and through which policy paradigms change provides an interesting methodological tool (see also Wood and Flinders, Citation2014). As Wood (Citation2015, pp. 4–5) notes, Hall’s approach is illuminating as it focuses attention on the scale of policy change and provides a framework for tracking such changes. But whereas Hall mostly emphasises a more rationalistic process of social learning (‘puzzling’) through testing, learning and revision, a growing body of literature on paradigm change, as Wood (Citation2015, pp. 8–9) points out, sees processes of discursive conflicts and contestations of ideas or interests (or ‘powering’) as equally important to paradigm change. For Wood this ‘powering’ implies pushing for certain policy-views through political and other means ‘external’ to policy-learning. Moreover, ‘powering’ can be used equally for both politicitisation of policies and policy-views as well as for their depolicitisation.

In its most elementary, ‘philosophical’ form politicisation is simply about claiming options, that there is an alternative to a current state of affairs or to an existing policy, whereas depolitisation claims the opposite: that the alternative at hand is the only viable option in a given situation. Of course, alternatives are always claimed for almost any given state of affairs or policy. Thus politicisation must be seen as a matter of crossing a certain threshold in the intensity of contestation. In research politicisation is often perceived as a matter of (significant) change in the way that a given policy is contested.

This of course is by itself insufficient for operationalisation – for discerning politicisation (or the lack of it) being present in a given context. For operationalisation, we use the definition set by Hackenesh et al. (Citation2021). They follow de Wilde et al. (Citation2015) in defining the politicisation of a given issue to be a reality when (1) salience of the issue, (2) polarisation of opinions and views over the issue and (3) expansion of actors participating in the debates and contestations over the given issue, or showing an interest in them, all significantly increase.

Domestic political forces influencing aid

To understand, in turn, the domestic political forces behind Finnish aid, we also draw on Lancaster’s (Citation2007) simple heuristic framework, in which she identifies four categories of domestic forces shaping development assistance. They include key ideas (or worldviews) of development; political and economic institutions shaping decisions on aid; interests and interest groups driving aid; and the organisation of aid agency (Lancaster, Citation2007, pp. 18–22). Lancaster’s very general notion of ideas of aid resembles somewhat that of Hall’s (Citation1993), but she concentrates mainly on norms and values.

In our article Hall’s work on paradigm change provides a theoretical model for understanding the thinking and rationale underlying (Finnish) aid-policy framework, while Lancaster directs our attention in a more pragmatic fashion to certain domestic forces and their dynamics in certain specific locations in the policy arena. In this study these forces are important to understand dynamics around aid volume. For the purpose of this study, political and economic institutions as well as organization of aid agency are key.

To understand in turn the role of political and economic institutions shaping aid and aid volumes in any country, it is essential to look briefly at the locus of the authority of aid-related decision-making in the domestic policy arena. In Finland, the interaction between Parliament, the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs (MFA) and the Ministry for Finance is key. Relatedly, ‘the nexus’ between the economic institutions and the budgetary process and the political parties in government is in turn decisive for defining the level of the Finnish development assistance. In the Finnish case, we will also look at the organisation of the aid agency together with political institutions, as it is so closely linked to the role of development policy in the Finnish political system.

As Hackenesh et al. (Citation2021, p. 4) note, politicisation may take place firstly in formal institutional arenas, such as parliaments and spread from there, but also in any political (or administrative) decision-making body that allows for a certain level of public debate about a policy or an issue. Or politicisation can happen in the public arena, meaning public opinion as a locus of politicisation (Hackenesh et al., Citation2021, p. 8). The same applies to depoliticisation.

On the research process, methodology and data

Before turning to 0.7 per cent question itself, our overview of the Finnish aid paradigm focuses on two of the fundamentals, that is, the perceived purposes of aid and the expressed intentions related to its material basis. Both would be important for aid as a whole as they influence and constrain more specific goal setting, thematic priorities, aid instruments and programmes. While drawing on earlier descriptions of Finnish aid (see Koponen et al., Citation2012; Koponen and Siitonen, Citation2005; Siitonen, Citation2011), we need first to gather and update the missing pieces and track the stated trends in the evolution of the Finnish aid paradigm. We start by examining official development policies (in all nine key documents) through some of the key features of Hall’s concept of paradigm. Our analysis begins with the first published government-level development policy (Citation1993) and its core elements. We then look at how these have evolved in ensuing policies, identifying the main elements of continuity and change, as well as degrees of change (Hall, Citation1993). In parallel with the policy programmes, we follow the actual trends in aid volume and the official commitments to the 0.7 target by each government term in office 1993–2021. To explain the changes in levels of Finnish aid, we inquire deeper into the domestic political forces shaping aid, following Lancaster’s framework. To demonstrate how these forces affect aid in practice, we then take a look at the main periods of change in aid volume (centred in 1991 and 2015) through the concept of de/politicisation (Wood, Citation2015).

Our data includes independent development policy reviews and parliamentary reports. We also use party and election platforms to help understand political parties’ positions. Another key source is the OECD DAC reviews, as well as some of the evaluations commissioned by the MFA. We use statistical data from the MFA statistics unit. We also carried out 10 complementary interviews with politicians, government officials and other stakeholders who have participated in shaping of Finnish development policy.

Framing the foundations for the Finnish aid paradigm (1993)

The first development policy founding the Finnish approach

Finland officially launched its first official government-level ‘development cooperation policy’ in 1993, entitled Finland’s Development Cooperation in the 1990s. The policy explicitly stated the goals and operational principles for Finnish development aid in a comprehensive and systematic form. As the 1995 OECD DAC review notes, the 1993 policy consolidated established development cooperation policy, but it also placed new emphasis on certain elements (OECD DAC, Citation1995, p. 14). First, the policy outlined Finland's approach to aid and a strategy to reduce poverty and inequality. By so doing, it also clarified Finland’s position on international processes related to development at the time, and – most importantly to domestic audiences – a Finnish take on more effective aid management and spending. Furthermore, it established the development cooperation as an essential part of Finland's foreign and security policy and trade (MFA, Citation1993, Preface). This understanding guided the understanding and organisation of aid policy in the MFA throughout the 1990s (The Level and Quality of Finland’s Development Cooperation, Citation2003, p. 4).

The policy was formulated amidst the economic turmoil of the early 1990s, when Finland was hit exceptionally hard by one of the worst banking-crises in Western Europe (Dang et al., Citation2013, p. 233). The aim of the 1993 policy was to make Finnish aid, significantly expanded in the 1980s but now dramatically cut in the recession, more ‘planned’ and ‘results-orientated’, a model explicitly following private enterprises (MFA, Citation1993, Preface). Moreover, the end of the Cold War required a revision of Finnish aid for foreign policy reasons (MFA, Citation1993, p. 8).

The policy also emphasised new global problems and threats – from environment to population growth (and ensuing migration), terrorism, drugs and pandemics – that required international cooperation (MFA, Citation1993, p. 8). On the economic front, the policy noted how developing countries were now a divided group. In the 1980s, many developing countries suffered crippling debt. Now, the world economy was said to be lifting some countries up, because they had already integrated into it, while leaving others behind, because integration had not happened (MFA, Citation1993, pp. 8–9).

The policy also argued that the perception of developing countries as ‘targets of world-wide social policy’ could no longer be maintained. Instead, developing countries were to be seen as countries, along with all others, existing in mutual interdependence (MFA, Citation1993, p. 9). The policy speculated that taking (in rich countries) these mutual interdependencies affecting developing countries into account in other policy-areas than aid – agriculture, trade, employment and immigration, for instance – might perhaps change the significance of aid in the future and perhaps even reduce it, if the same goals could be achieved in the future ‘with different means’ (MFA, Citation1993, pp. 9–10). This idea resonates in the concept of policy coherence for development enshrined in the Maastricht Treaty (1993).

The main purpose of Finnish aid was designated as three-fold: poverty reduction, protection against global environmental threats and the promotion of democracy, human rights (and good governance and rule of law). Finland would set out to pursue these goals through dialogue, influencing its multilateral partners, through design of specific projects and programmes and through its support of non-governmental organisation (NGO) activities. However, the policy was rather thin on how the goals were to be realised, stating that the policy in question was only the ‘upper’, strategic level of a declaration of the goals and principles guiding Finnish aid (MFA, Citation1993, p. 7).

To promote poverty reduction, the policy stated that Finland’s aid was intended to be directed to the world's poorest countries. Here, it was seen that aid should go to sectors that on the one hand satisfy directly basic needs (such as water or basic health care) and on the other facilitate economic development (infrastructure, small business, and sustainable forestry and agriculture) (MFA, Citation1993, p. 16). Likely influences for these views are, for example, the World Bank World Development Reports of the time (especially World Bank 1990).

The 1993 policy states that the precondition for Finland’s aid is in every case a ‘will to develop’ on the part of a given country and its people (MFA, Citation1993, pp. 14–15). It becomes evident from various statements throughout the policy is that this ‘will to develop’ was seen to hinge most on a willingness to adopt economic and trade policies considered to be of ‘right’ kinds, even though economic conditionality was not explicitly endorsed. This stance in turn opened the door to what was regarded as mutually beneficial economic relations and Finnish export promotion, perhaps even through tied aid.

Main continuities and changes in the Finnish aid paradigm

Between 1993 and 2022 Finland revised development policy eight times (MFA, Citation1996, Citation1998, Citation2001, Citation2004, Citation2007, Citation2012, Citation2016 and Citation2021). Prior to the centre-left government of 2019, this chain of separate programmes was backed by an implicit notion that each government should decide its own development policy approach. This has been the case especially in the period 2004–2016. Then, each government reformulated its development policies from the scratch under differing thematic headings but with remarkably similar overall goals and principles, channels and instruments (Evaluation, Citation2015; Reinikka, Citation2015, p. 27). The ministers responsible for development have also sought to leave their mark on policy, while the overall responsibility of policy formulation has rested with the aid administration (Reinikka, Citation2015, p. 27; Interviews). The latest policy, that of 2021, has for the first time the explicit aim of transcending single government terms of office.

summarises the evolution of Finnish Development Policy since 1993, showing both continuities and changes that we have identified in all nine documents using Hall’s policy-paradigm framework (especially the category of ‘policy goals’) as a guide. Mapping the key elements related to the purpose of aid shows that the 1993 policy not only established a framework for the future policies but contained elements that became permanent features of the Finnish aid paradigm. Within the limits of this article, we can only very briefly discuss each of the main elements, acknowledging the need for more thorough analysis.

Table 1. Finnish Development policies since 1993: Continuities, Changes and 0.7 Commitments.

The elements of continuity in the development policies include, first, poverty reduction as the stated main purpose of development aid. However, it is often presented in a cluster of other goals and/or themes. As Koponen and Siitonen (Citation2005, pp. 218–219) and OECD DAC (Citation2003, p. 237; Citation2013, p. 12) have critically noted, this model of goal setting has risked blurring the poverty focus and creating confusion between goals and means. Also, the order of the main goals perhaps changed once, in 1998, as a new goal of ‘increase in world-wide security (and peaceful development)’ seemingly superseded poverty eradication as the first on the list of the main goals for one government term. The two other main goals set in 1993 – protection against global environmental threats, and human rights and democracy – have also remained firmly on the agenda over the last three decades, though with varying emphases, roles and accompanying aims. Gender equality, too, was introduced as a ‘cross-cutting topic’ already in 1993, but it took two decades to be established as a ‘cross-cutting objective’, in 2012. The line-up of goals has also tended to expand from one government to another, regardless of the volume of aid.

In addition, the poverty focus has varied from poverty reduction (1993–2001) to eradicating extreme poverty (MFA, Citation2004, p. 7) and to reducing poverty and inequality (MFA, Citation2016, p. 13), while the most recent policy defines it as poverty eradication and reduction of inequalities (MFA, Citation2021, p. 11). A stronger focus on inequality was incorporated into the 2012 policy, which brought the human rights-based approach to the centre of Finnish development policy. The wider context of poverty reduction has also evolved. The first development policy referred to sustainable development already in 1993. This was enhanced in 2007 as a precondition to poverty eradication (MFA, Citation2007, p. 12) and with the UN 2030 Agenda for sustainable development became the overarching framework for development policy in 2015, replacing the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

Second, the role of development cooperation as a tool to address, at least in part, a wide variety of global problems can be identified from the onset of the first policy. For instance, tackling environmental degradation and the unsustainable use of natural resources (since 1993), conflicts (strong emphasis in late 1990s and early 2000s), climate change (2007-), the root causes of migration (2016-), and biodiversity loss (2021-).

Third, there is the primacy of other means besides development aid, most notably economic policy, trade and investments, that are seen as appropriate for advancing development in parallel with development aid, with the explicit hope that these measures could even gradually replace aid in the future (for current international trends in going ‘beyond aid’, see Janus et al., Citation2015; Mawdsley et al., Citation2014). From the 1993 policy onwards, Finland has emphasised policy coherence for development (especially between 2004 and 2015) in the policy documents. It has also highlighted together with the UN and DAC, that ODA-funds will never be enough for sustainable development, and that therefore for instance, Finnish companies must be encouraged to get involved in development (already in MFA, Citation2004, but especially 2016 and 2021).

Fourth, development policies stress the importance of Finland’s own interests in the aid paradigm, implying that their advancement ‘on the back of’ development is acceptable and it can be accommodated directly or indirectly. Directly, for instance, by supporting Finnish companies’ export- and investment opportunities in the 1990s through concessional credits, and again especially since 2016 policy with financial investments. And indirectly, for instance, by creating a peaceful and non-threatening world specifically for Finland (MFA, Citation2001 and onwards).

This takes us to the fifth element of continuity, concerning the selection of aid channels, instruments and beneficiaries. The selection of main channels has remained largely the same as has those of main instruments. The most notable change in this context has been the rise of financial investment instruments from 2015 onwards, discussed in Section 4. Within bilateral aid, however, Finland seems to have struggled with two opposing tendencies in aid allocation: an expansion of recipient-country numbers and a concentration on fewer countries, with the primacy and continuity of the former. The expansion has reflected Finnish foreign and commercial policy interests (Koponen and Siitonen, Citation2005, pp. 229–230) but also geographically fragmented NGO support (Reinikka, Citation2015, pp. 39–40). This has been criticised for diluting Finnish aid’s impact (OECD DAC) and for working against the stated concentration criteria for selecting partner countries based on their poverty (The Level and Quality of Finland’s Development Cooperation, Citation2003, p. 2; MFA, Citation2004, p. 28; OECD DAC, Citation1995, pp. 22–23).

In 1993, Finland had 13 ‘primary cooperation countries’, in line with the criteria of concentrating aid on the poorest countries, but ‘project-based assistance’ was also provided beyond this group. According to Koponen and Siitonen (Citation2005, p. 230), Finland's EU membership in 1995 confronted the policy with demands to materially support the EU’s policies. A ‘more flexible policy in the choice of partners and widening contact surface’ was declared and a different type of assistance was to be extended to a different type of countries and different geographical locations, including Eastern Europe (MFA, Citation1998; see also OECD Citation1999). At the end of the 1990s, about 100 countries were receiving Finnish aid (Koponen and Siitonen, Citation2005, pp. 229–230). The 2004 policy aimed to reverse this expansion, and reduce number of recipients and focus on the LDCs (MFA, Citation2004, p. 27).

Since 2007, the long-term partner countries have been mainly LDCs and fragile states in East Africa as well as Afghanistan, Nepal and Myanmar in Asia (with a transition phase with Vietnam since 2015 and Zambia since 2019). In Africa, Finland's main bilateral partner countries are currently Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Somalia and Tanzania. Finland has also supported the Palestinian Territories and efforts to respond to the crisis in Syria have increased during the last ten years. However, the coups in Myanmar and the Taliban take-over in Afghanistan and the subsequent suspension of aid in 2021 have left the question of the future role of the main partner countries unresolved. In addition, the number of beneficiaries beyond this group has remained large. In 2015 it was 94 and in 2020 70 countries (MFA Statistics, Citation2022).

And finally, alongside these five continuities, there is the continuing striving for the 0.7 target from one government term to another, as shown in . Even though the target has not been met since 1991, it continues to feature in government programmes and development policies as an essential feature of the Finnish aid paradigm defining Finland’s aspirations and self-image as a Nordic donor.

Within all the core elements of continuity, a number of adjustments could of course be identified that would qualify as first-order changes in Hall’s (Citation1993) terms. However, the core elements and characteristics of Finnish aid have largely remained the same at the policy level. But there are also some more fundamental changes, that meet Hall’s criteria for second-order change. Intriguingly, these changes are not related to the paradigm per se as expressed in government policies, but to its funding in practice and some of the instruments. Thus the main second-order changes in Finnish aid relate to instituted changes in the volume of aid and to the rise of a new category of instruments called financial investments (from 2015 onwards).Footnote3 We now turn to discuss the changes in actual aid volume and then look at the domestic forces behind these changes.

Finland’s efforts to reach the 0.7 target: ups and downs in aid volume

In the 1980s, Finland sustained the fastest growing development cooperation ever recorded in the OECD DAC in its funding relative to GNI (OECD DAC, Citation1995, p. 13; Paasio, Citation1996, p. 11.) This upward turn was soon halted by probably one of the worst banking crises in Western Europe and the consequent economic recession (Dang et al., Citation2013, p. 233). The recession resulted in dramatic cuts to government budgets, especially for development cooperation. Finland’s all-time record high of development aid disbursements of 0.76 per cent of the GNI in 1991, the only time ever when the country momentarily reached the 0.7 level, dropped to an all-time low of 0.29 per cent in 1994 (MFA Statistics, Citation2022). Despite the economic shock, the 0.7 per cent GNI goal was never abandoned. In fact it was re-stated in each subsequent government programme, but the conditional ‘when the economy permits’ was appended to it for decades to come. The drastic cuts were first excused as a temporary measure (Government programme 1991). By 1995, economic recovery was already on the way and by the end of the decade, Finland was back at the top of the ranking lists of the world’s most competitive and technologically advanced economies. Yet, Finland’s efforts to advance 0.7 were lagging far behind (OECD DAC, Citation1995, p. 31; Voipio, Citation1998, p. 31) ().

After the recession, the first 10-year period from 1994 to 2004 was marked with a slow uphill struggle in aid disbursements/GNI from 1994 to 2004, during which the share of the ODA fluctuated at around 0.3 per cent of the GNI. In 2005, the Finnish aid disbursements finally jumped to 0.44 per cent. In addition to the country’s good economic situation, a centre-left government in power, and pro-0.7 campaigning taking place, the obligations attached to Finland's EU membership and the joint EU aid-targets seemed to start to take effect (Delputte et al., Citation2016, pp. 77–78; Rekola, Citation2005; Interviews). Despite a slight downturn in 2006-2007, Finnish aid was again on a positive curve from 2008 until 2014. In fact, the 0.7 target was closest in 2014, with an all-time second highest level of 0.59 per cent of GNI. This was facilitated by a stronger economy, a favourably inclined centre-left majority government constellation, determined development ministers, and an active NGO lobby (Interviews). However, the positive tide was to end dramatically with the change of government in 2015. In just a few years, Finnish ODA dropped again drastically, from 0.59 per cent of GNI to 0.36 in 2018.

Despite the stated LDC focus for poverty reduction reasons, Finland’s average share of ODA to LDCs was about 0.12 per cent in 2000–2010 (Siitonen, Citation2011, p. 16). The share of LDC funding started to pick up anew in 2008 and Finland maintained this upward course close to 0.2 GNI until 2015, even superseding it in 2014 as the overall ODA share of GNI also rose. In turn, the steepest decreases in aid to LDCs seem to go hand in hand with the decline of the overall aid level, as in 1991 and from 2016 onwards. Between 1991 and 1994, Finnish aid to the poorest countries shrank from 0.3–0.1 percent of GNI. Similarly with the massive cuts of 2015, the share of ODA to the LDCs declined from 0.18 per cent in 2015–0.13 per cent of GNI between 2016 and 2017.

As for the current government, the Social Democratic Party (SDP)-led coalition government did introduce an increased aid disbursement from 0.42 in 2019–0.47 in 2020. But despite a joint commitment enshrined into government programme of 2019 ‘to prepare a roadmap and timetable for attaining the 0.7 goal’, the attempts to do so have so far failed but have not been abandoned. In the latest report by Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee (Citation2022), the committee reiterates its long-standing view of the importance of both 0.7% and 0.2% targets and considers it important that funding be increased systematically and gradually towards this target.

To understand the difficulties to reach the 0.7 target, we now turn to the domestic political forces to find possible explanations and to identify probable obstacles.

Explaining the dynamics behind the Finnish aid volume: domestic political forces and the 0.7 target

Political institutions and coalition politics

In the Finnish multiparty system of proportional representation, the power of the government has usually been shared among three or four of the main political parties. In recent elections, the winning parties have each carried only about 20 per cent of popular support. The rest of the seats in Parliament are divided among the smaller parties. Currently, the largest parties include the Social Democratic Party (SDP), the conservative National Coalition Party, the populist Finns Party (which joined the ranks of the main parties in 2011), then the Centre Party (formerly the Agrarian League), followed by the Greens, the Left Alliance, the Swedish People’s Party, the Christian Democrats and, since 2019, Movement Now (Statistics Finland, Citation2019). This array of parliamentary parties may result in large government coalitions with politically unconventional combinations, such as so-called ‘blue-red’ or ‘rainbow’ governments of parties from the whole political spectrum.

The large government coalitions tend to increase the number of policy issues that have to be negotiated, which may also affect the position of development policy on the government agenda, especially when the government programme and budget are being negotiated (Interviews). The parties aim to keep their positions open to ensure better positions in the future governments. Fixed positions would narrow their options. On the other hand, each party has core priorities that they need to defend. In budget negotiations, development policy is often played off against domestic welfare concerns, which makes advocating international commitments difficult (Interviews). In practice, those parties or individual politicians that profile themselves as pro-aid may push for development financing, but it has never been a deal breaker. As a result, no political party has risked its position in the government for development assistance during government negotiations or while in office.

A review of party and election platforms (2011–2019) shows that the main parliamentary parties tend to formulate their support for the 0.7 target as a commitment that ‘Finland’ should fulfil rather than expressing direct commitment to it as a party. Only the smaller parties, including the Left Alliance, the Swedish People’s Party and the Christian Democrats, formulate their commitment in this way. As for the point of development policy, only the SDP and the Greens see its purpose in the ultimate goal of poverty reduction, while other parties just list separate themes for the policy to implement (see for instance, The Greens Elections platform, Citation2015; SDP, Citation2018). All parties highlight the importance of wider foreign policy goals and addressing global problems in connection with aid. Also, Finnish commercial self-interests are present and have a stronger profile among centre-right parties.

Concerning support for development policy and cooperation, of the large parties the SDP has historically been considered to be most in favour. The party has also been active on the Nordic scene and associated networks (Interviews). Conversely, the National Coalition Party has generally been less keen on development policy at programme level, although it has emphasised Finland’s responsibility to the poorest countries and its wider global responsibility (Kokoomuksen vaaliohjelma, Citation2011; Kokoomuksen strateginen vaaliohjelma, Citation2015; Kokoomuksen periaateohjelma, Citation2018). Formally, the Centre Party has advocated the 0.7 target since in 2003 and this commitment has been re-affirmed in its 2011 and 2019 in elections platforms (Interview; A Better Finland: Centre Party Elections Platform, Citation2015). Of the current main parties, the Finns Party has been overtly sceptical towards development cooperation’s legitimacy, except humanitarian aid. In its view, development aid must be strictly conditional and major part of it should be collected through a voluntary tax or levy and not financed from the state budget unless there is surplus (Foreign Affairs Committee of Parliament, Citation2022; Perussuomalaisten talouspoliittinen ohjelma, Citation2015).

Apart from the Finns party, the positions of the parties are not fixed and the views of the parties on the purpose of aid and the 0.7 target vary. But crucially, the 0.7 target is still widely considered somewhat abstract. That is, the link between the purposes of aid, the 0.7 target as well as the possible benefits from increasing funding have remained vague. In the competition between different interests, this works against achieving the target. It is also perceived to be too difficult to form within the parties a critical mass in support of development aid and its financing and to get their leadership to commit to the cause (Interviews). Hence, development aid appears to be a rather low priority issue for Finnish parties.

In sum, given the typical process of Finnish government formation and the lack of powerful, pro-aid stances by the bigger political parties and the absence of cross-party pro-aid coalitions make it unlikely that the status quo would change through politicisation in favour of the 0.7 target. On the other hand, the rise since 2011 of the Finns party, which is openly aid-sceptical, further challenges any attempts to promote the 0.7 target.

It is noteworthy that in the light of the Development Barometer (commissioned by the MFA 2002–2021 to Taloustutkimus/Economic Survey), support for development aid has in fact been rising among Finns since the 2000s.Footnote4 A positive general attitude has not, however, been reflected in the evolution of development spending, party programmes or in parliamentary debates.

The locus of authority in development policy content lies with the government, particularly the MFA and the minister in charge of the development cooperation portfolio. The decision-making power on development shifted from Parliament to the MFA in the mid-1990s (Paasio, Citation1996). Since then, Parliament's involvement has narrowed down from former substantive and direct involvement (including the selection of partner countries and aid allocations) to simply approving budget totals and debating finalised policies (Paasio, Citation1996; The Reality of Aid, Citation1996; Interviews).

Since 2016, Parliament has approved final development policies, which are published as Government Reports. They are discussed in plenary sessions of Parliament both before and after circulation in relevant committees for statements. Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee then reports back to the plenary based on this process. At this occasion, parliamentary parties may present their views on the report and discuss them in the plenary. In terms of engagement and awareness, this process is important and could offer openings for politicisation (Interviews). Also the latest development policy of 2021 was prepared jointly by the MFA and an interparty parliamentary committee. But so far these efforts have not resulted in the politicisation of aid and the interest in these debates has remained low both among the political parties themselves and the media (Interviews).

The integrated organisation of aid agency and interests related to aid

Notably, Finland has never had a development minister responsible only for development issues, as the portfolio has always been shared between other policy sectors. Under the MFA’s institutional reform at the turn of the millennium the separate aid section Finnida was dismantled and integrated into the ministry’s new institutional setting at the turn of the millennium. In this process, the section was brought under the Development Policy and Regional Departments, alongside the Political and International Trade Departments. This integrated structure may have had implications for the Finnish aid paradigm, especially concerning the wide array of issues related to the purpose of aid, its goal-setting and the number of beneficiary countries beyond LDCs. Since 2003 development policy has been coupled with external trade (OECD DAC, Citation2003, p. 9). As Lancaster (Citation2007) points out, the organisation of aid agency matters, as the integrated external relations structure can be identified in the continuation of Finnish development policy content. In particular, these integrated elements also echo Finnish external policy self-interests, as discussed above. Of course, this is not unique to Finland, as a variety of interests can be pursued through aid (for a discussion on this, see Riddell, Citation2007). These can range from altruistic motivations of solidarity towards other countries to donor’s own various economic or foreign policy interests.

The interrelationship between the organisation of aid agency and aid volume is much more indirect. For instance, promoting aid in parallel with Finnish self-interests through foreign and commercial policy may have sometimes been one factor favouring an increase in aid financing (Interviews). From a historical perspective, Koponen and Siitonen (Citation2005, p. 225; Siitonen, Citation2011) have explained how development aid and the volume of aid played a role in the construction of Finnish international identity and attempts to build the image of ‘a neutral member of the Western bloc’ during the Cold War. In order to maintain such a profile with any credibility, the level of aid had at least to approach the levels of other Nordic states (see also Antola, Citation1978). After the Cold War, there was no further need for this and the importance of the Nordic group started to fade in this regard. With Finland’s accession to the EU in 1995 and the need to substantiate the claim to be in the ‘core’ of the EU, the role of aid volume and targets again appeared to be instrumental for Finland, but with less pressure to follow in the Nordic peers’ footsteps in terms of aid volume (Siitonen, Citation2011, p. 8).

Another feature that relates to aid agency and aid volume is administrative costs. In times of economic downturn, cuts are often directed both at aid as well as to aid administration and personnel resources. This has resulted in a lack of personnel resources in key areas of aid potentially endangering not only aid quantity but also its quality. Insufficient personnel combined with frequent staff rotation, due to heavy reliance on diplomatic staff, have limited institutional memory and knowledge generation. This in turn has been identified as among the key challenges to social learning at a development policy level and its content (MFA, Citation2019; OECD, Citation2017, pp. 23, 62; Ylönen and Salmivaara, Citation2021).

The plurality of interests is echoed also in the stakeholder representation in the policy arena. Ever since the formation of Finnida in 1965, key stakeholders have always played a role in the formulation of development policy in a some organised manner (Nogueira de Morais and Virtanen, Citation2015, p. 422). In 2019, this structure was institutionalised by the Government Decree on the Development Policy Committee (1071/2019). Its members include representatives of political parties, non-governmental organisations engaged in development cooperation, the business community, research community, agriculture and trade unions as well as expert members from sectoral ministries. Essentially, the committee is an advisory body to the government and a forum for stakeholder dialogue and knowledge production. The committee is chaired by three MPs representing the government and opposition alike. Unlike, for instance, its Danish counterpart (Advisory Board), the Finnish Development Policy committee does not have any decision-making power, which lowers its political appeal for the political parties and decreases the tension needed for politicisation. Representatives of political parties (one MP member/one substitute) are usually the ones who are interested in global issues and who advocate for aid in their respective parties. The membership supports them in this effort but it does not remove the main obstacles that pro-aid parliamentarians face in promoting the 0.7 target vis-à-vis the political and economic institutions discussed in this article.

In practice, the committee provides one institutionalised avenue for policy advice and advocacy but does not substitute direct channels between stakeholders and the government. The Confederation of Finnish Industries, agricultural lobbying groups and the umbrella organisation for Finnish NGOs KEPA (since 2018 Fingo), larger civil society organisations and NGOs working on thematic sectors in particular play a role in their own right and are vocal on the issues concerning their own subject area. In addition, consultancy companies are peculiarly heavily involved in Finnish aid (see for instance Voipio, Citation1998; White, Citation2020).

Overall, the Development Policy Committee provides a framework for a host of actors to influence the policy area and to join forces. But its consensual working method is not conducive to politicisation. Regarding the volume of aid, the members sign-up for joint statements to advance 0.7 and 0.2 targets that reflect the position of their member organisations. But in the case of the Finns party, a note of dissent is usually added without further debate.

The economic institutions setting the limits to aid: ministry of finance and the budgetary framework

In many respects, the Ministry of Finance plays a key role in development assistance. As the list of the governments’ commitments to the 0.7 target shows, the conditional tag ‘when the economy permits’ was appended to them at the beginning of the 1990s and this has persisted until today with few exceptions. While no specific criteria have been set for this conditionality, the Ministry of Finance is in a crucial position to set the scene for budget negotiations. It provides its own analysis of the state of the economy, forecasts economic trends, and on the basis of forecasts sets government spending limits, the so-called expenditure framework. This is a spending ceiling agreed in advance by the government for the duration of an electoral period, not to be exceeded. Each year, the framework sets the ceiling at about 80 per cent of government budget expenditure – leaving only 20 per cent for later discretion, to be subsequently shared among all budget items. The expenditure framework is not enshrined in law, but its institutionalised role is based on an agreement between the political parties.

The framework sets a prior limit on the scope for negotiation, especially on rather marginal items in relation to domestic politics, such as development assistance. The Ministry of Finance is therefore often regarded as the first gatekeeper in budget negotiations, exercising both direct and indirect power in framing the debate and defining what is possible/advisable to do. This is important concerning the politicisation/depoliticisation of aid and the scope for any alternatives. In some cases, the ministry has made direct statements on aid spending, although it is not their policy ambit (Koponen and Siitonen Citation2005, p. 224; Interviews).

Despite the official commitment to the 0.7 target, development financing is discussed like any other item in the state budget process. No collective outcome that would confirm the 0.7 commitment is sought but rather development financing is played against any other expenditure items, including domestic welfare needs (Interviews). This was also the case in 2019, when the state budget was for the first time officially based on the Agenda2030, with the 0.7 per cent target incorporated into SDG-17. Should the 0.7 target be considered important enough, the Ministry of Finance would have the authority to propose the inclusion of the target into the 80 per cent expenditure framework (Interviews). So far it has not used this option.

There is an additional challenge in that development policy formulation and financing do not quite go hand in hand in terms of planning and timing. The process of setting the content of development policies (their goal setting, ambition levels and instruments) are detached from planning the budget at government and ‘corporate’ levels (MFA, Citation2015, p. 10). This in turn makes it possible to extend policy objectives and the purpose of aid even at times of massive aid cuts.

As politicised as it gets? The rise of 0.7 in 1991

The political and economic forces of Finnish domestic politics discussed in this article have so far contributed to a model in which the pursuit of the 0.7 target continues rather than materialises. This begs the question of why the increase of aid to 0.7 did actually happen once, in 1991, and what factors enabled it and led, momentarily, to more politicised aid?

In light of previous literature and some of our research interviewees present in policy-making in 1991, we assume that a number of factors contributed to highlight the salience of aid and generated wide-based support (with very little opposition) in the political and economic context at the turn of 1990s. This short period therefore marked the most politicised momentum in Finnish aid, partially meeting the criteria for politicisation, but without any real polarisation of opinion against aid increases.

First, the aid level was already relatively high (0.61 per cent/GNI in 1989) and the economic situation in Finland was exceptionally good, with one of the fastest growing GDPs in the OECD (Citation1995, p. 13). Second, aid was seen to promote both Finnish national economic and foreign policy self-interests, especially export promotion, in the 1980s, and third, a group of influential and internationally well-connected activists that created the One Percent Movement championed the 0.7 target through different channels. For the first time, poverty eradication and aid were advocated in an organised manner to policy-makers and the public alike. Fourth, the members of the movement were closely allied with high-level politicians, especially those in the SDP but also leaders of other parties. In addition, they appealed directly to people to pay one per cent of their pay to NGOs working in developing countries. The campaign started in the early 1980s and largely achieved its aims by 1984 as the SDP-led government renewed the Finnish commitment to the 0.7 GNI target and started systematically to increase aid. In addition, more than 100 000 individuals signed to the one per cent principle (Rekola, Citation2005, p. 9; Interviews).

The record year in Finnish aid was a year of elections, which started under government of the National Coalition and SDP, accompanied by the Swedish People’s Party and the Agrarian League (1987–1991). For all these parties, Finland’s membership of the UN and the Nordic group was crucial, and aid and the 0.7 target were seen as key prerequisites for belonging to these communities (Interviews). This constituted the fifth factor that worked in favour of the 0.7 target being attained in 1991. However, even in these favourable circumstances the ‘triumph’ was partly incidental as aid funding rose at the same time that GNI started to fall.

In the Spring of 1991, a centre-right government was elected with the lead of the Centre party and the National Coalition party (1991–1995). The new government was faced with an unprecedented economic shock as a consequence of a banking crisis. The following year, it introduced a set of measures that led to a drop in aid volume, as described above. It was stated that this decrease would be temporary, but in reality aid stagnated at a chronically low level. The recovery plan tied aid volume to the perceived state of economy without any clear criteria related to a sufficient improvement of economic indicators. Making any progress towards 0.7 conditional on the state of the economy has not been politicised since then. This dramatic collapse of aid funding in the early 1990s marked a second order change, a change that the government programme stated would be a one-off. But in 2015 it happened again.

Depoliticised economy and cuts in aid volume 2015–2016

The depoliticised nature of aid seems to be highlighted especially in periods in which Finland’s overall economic policy comes under political scrutiny. The change of government from centre-left to centre-right in 2015 serves here as a case in point. In spring 2015, the Centre Party, the Coalition Party and the Finns Party won the parliamentary elections and formed a majority government. In his speech to Parliament on the new government programme, Prime Minister Sipilä (Centre Party), expressed the government’s concerns about imbalances in the Finnish economy and paved the way for ‘unavoidable austerity measures’:

When reform is neglected for a long period, cuts become unavoidable. We must now focus both on saving money and fully implementing major reforms. Finland has only two alternatives. Either we carry out these reforms ourselves or someone else will carry them out on our behalf … .

The government announced a list of sectors that either needed reform and/or cost saving to tackle the budget imbalance. ‘Warnings’ from the EU and the IMF were used to increase the pressure to carry out the measures. The Finnish welfare state, no less, was posited as being in jeopardy (Prime Minister’s Speech 15 June 2015). This list of cost savings included freezing indexed increases for pensions and other social transfers, development assistance as the largest single item on the list to be directly reduced, as well as cuts to such things as social benefits, education, and research and innovations funds. As a result, the share of Finnish ODA disbursements fell from 0.59 per cent of GNI in 2014, the pre-election year, to 0.38 per cent in 2018 (MFA Statistics, Citation2022). The €118-million refugee reception costs of 2016 were more than 200 per cent higher than the previous year. Without these costs, the percentage of Finnish ODA would have looked even gloomier ().

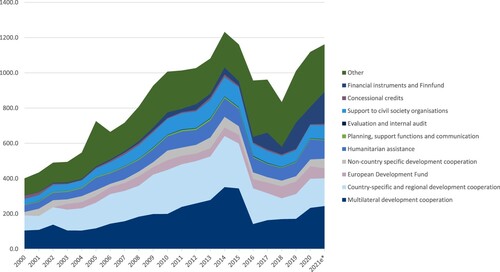

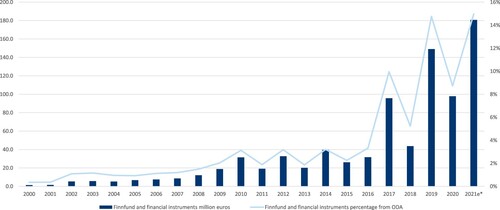

Alongside the cuts, the government created a new instrument referred to as ‘financial investments’ outside the state budget. This shift was made possible by converting €140 million annually from grant aid into loans and capital investments (Financial Affairs Committee of Parliament, Citation2015). From the perspective of state finances, loans and investments were preferred over grant aid as they did not increase the budget deficit (Financial Affairs Committee of Parliament, Citation2015; Interviews). For the development community, the government marketed this shift as a way to stop additional cuts and to secure more funding for ODA ‘in a different form’ (Interviews). Among the main beneficiaries of this re-allocation was Finnfund, a government-steered development financier supporting private sector investments in developing countries involving Finnish interests (Finnfund Act, Citation1979). Although Finnfund had already operated since the 1980s, the shift significantly strengthened its resources. It also enhanced the role of development financing institutions and their funding in Finnish development policy. Taken together, financial investments established a new and fast growing budget item from 2–3 per cent to 15 per cent of ODA between 2015 and 2021 ().

In the light of the election platforms of the winning parties, the case of development aid seemed a relatively easy target to agree on. Yet the magnitude of the cuts was a shock even within the parties themselves, suggesting that the final decision had been taken at the highest levels of the party leadership and government. In the budget negotiations, the Finns Party went as far as suggesting an end to state-funded development cooperation altogether (Interviews). Publicly, they insisted that the state could save by transferring the main responsibility for financing development aid to the individual citizen. Although the Finns Party did not gain support for this model and it did not materialise, it made even massive cuts to aid seem like an acceptable compromise. Moreover, the idea of foregrounding the Finnish economy and the country’s interests seemed to resonate across the centre-right government.

The cuts and conversion from grant aid to financial investments faced very little resistance among opposition parties (Financial Affairs Committee of Parliament, Citation2015). Nor did they prompt debate outside Parliament and its Foreign Affairs Committee (Foreign Affairs Committee of Parliament, Citation2015; Interviews). The Finnish NGO umbrella organisation, KEPA and other bigger NGO networks were almost the sole actors that questioned them publicly and in development debates. One reason was that parties opposing the aid cuts also opposed cuts to the social welfare, research and education sectors, leaving development aid on the sidelines (Interviews). The government reiterated that there was no alternative to the chosen austerity measures, while the opposition parties attempted to safeguard their other priorities (Interviews). As one interviewee pointed out, the cuts provoked more questions internationally than at home.

The cuts were not reflected in any way in the goals and declared measures of government development policy (MFA, Citation2016), which remained as broad in scope as in all previous policies. On top of this, in 2015 Finland adopted the UN 2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which became an additional overarching framework for aid and its purpose (MFA, Citation2016, p. 12). However, the equation between aid cuts and the broad policy scope was a problematic one. Although the new government’s own priorities, such as gender, were to be safeguarded, it did not work out in practice, as there was no time for transition and the cuts were simply too extensive. Neither did it allow for performance or results-based criteria, let alone social learning. Instead, Finland faced the era of SDGs with 38 per cent (or €330 million) less funding for the period of 2016–20 (OECD Citation2017, p. 43). This shifted the balance in Finnish aid from traditional aid channels in the direction of financial investments. Intriguingly, the actual cuts were not even mentioned in Finland’s development policy issued the same year, leaving the official aid paradigm’s view on aid volume intact. Instead, the policy referred once again to the long-term goal to raise the level of our development cooperation funds to 0.7 per cent of gross national income in accordance with UN goals, when ‘Finland’s own economy picks up’ (MFA Citation2016, p. 14). The government also maintained that the share of Finnish funding for the LDCs would remain above the international recommendation of 0.2 per cent of GNI. Neither pledge materialised.

To sum up, the drastic cuts and the rise of the financial investment instrument both marked second-order changes in Finnish aid that revealed the vulnerability of Finnish aid paradigm and changed Finland’s donor portfolio. The shift was not grounded on social learning in development policy but instead was ‘powered through’ (Wood, Citation2015) from outside the policy area by domestic political and economic forces in a largely depoliticised process.

Conclusions and issues for further research

This article was motivated by the need for a more scholarly analysis of Finnish aid and especially the ritualistic striving for the 0.7 target. We first sketched the background to the study by mapping continuities and changes (Hall, Citation1993) in the Finnish aid paradigm during the past three decades. To elaborate first on continuities, we identified some strong underlying characteristics concerning particularly poverty reduction, the role of aid, foreign and commercial policy self-interests as well as global concerns. The aspirations to reach the 0.7 per cent target are also a part of this continuum.

Like largely with the other Nordic peers, the long-term end goal of poverty reduction has prevailed down the decades, although its precise position in the aid paradigm, and consequently the purpose of Finnish aid, has often been rather ambiguous. In development policies, poverty reduction has often appeared to have been coupled with other development policy goals and even with competing aims, most notably from the other branches of external relations. This could be also noted in the rather unclear status of the Least Developed Countries in the Finnish paradigm. In a similar vein, and with some internal tension created in policy, Finland has seen the purpose of development aid as a means to address a wide spectrum of global problems, while simultaneously promoting partner countries’ developmental aspirations and Finland’s national interests.

Against this background, the role of aid volume is peculiar. Overall, aid is stated to be used for a wide variety purposes, yet none of these is perceived as compelling enough to end the 0.7 ritual and make it a reality. On the other hand, the importance of aid itself was often presented in an ambiguous manner in the policy documents, while other aspects, such as the ‘right economic policies’ in the recipient countries or the role of other Finnish policy areas were highlighted as being more decisive.

Although, the commitment to 0.7 has been one of the permanent features of the Finnish development policy throughout the three decades, in reality the significant changes in volume of aid have also constituted the most notable shifts that Finnish aid has faced. The magnitude, speed and impact of these changes qualify as second-order changes in Hall’s terms. Furthermore, new financial investment instrument rose mainly out of perceived economic necessities and interests, rather than from a desire to innovate or take into account the evaluation results of existing instruments through social learning.

To understand this contradiction and the difficulties of reaching the 0.7 target, we looked at the domestic political forces and obstacles for possible explanations. What we can conclude here, is that there are features in the Finnish domestic policy arena that relate both to the political and economic forces that hinder the fulfilment of the 0.7 target. The former included the structure of the Finnish government and coalition politics, where aid plays a minor role in competition with other domestic and – now also increasingly visibly – security issue-areas, in the absence of cross-party support. The case for 0.7 is further challenged by the budget procedure and the expenditure framework. Furthermore, the largely depoliticised nature of the economic considerations and these dynamics make it difficult to address these characteristics and to change the course towards the true commitment.

In the current acute security circumstances (war in Ukraine) and consequent humanitarian needs in Europe, it may be increasingly difficult to advocate for a large-scale raise in aid for developing countries. Instead, it will require even more effort to safeguard the continuity of the Finnish aid paradigm in its present form for now. But the urgent need for aid, for instance, to repair the ravages of the Covid-19 pandemic and climate change, highlights the importance of a solid aid approach and makes the 0.7 commitment too important to avoid.

In this article, we have only been able to provide a short overview to the Finnish aid thinking and to unpack the 0.7 puzzle. We hope that the interest in Finnish aid studies would attract scholars to continue from here. The perceptions of aid and the exact role perceived for it (both among decision-makers and the general public) in the contemporary world could be a potential topic of further research. It would be equally important to compare the intentions stated in policies with their actual implementation. There is also a need for more academic scrutiny of Finland’s efforts to go ‘beyond aid’ and to advance policy coherence for development.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the fellow contributors to the Forum for Development Studies Special issue on Nordic aid for their most helpful comments and lively discussions on the past and the future of Nordic aid. We also extend our gratitude to the two anonymous referees for engaging so thoroughly in the manuscript. Very special thanks go to Juhani Koponen and Lauri Siitonen for generously donating their time to the benefit of this article by commenting on it, and to Antti Putila, the intern at the Development Policy Committee, who worked also as our research assistant. We remain grateful to the Development Policy Committee's chairs, members and to the coordinator Katja Kandolin for constant encouragement and support for this project. Finally, our sincere thank you to our interviewees, who were willing share their insights into the Finnish development policy and aid.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marikki Karhu

Dr. Marikki Karhu (formerly Stocchetti) is currently the Secretary General of the Finnish Development Policy Committee. She serves also as an expert member of Finnish National Commission on Sustainable Development. Karhu's work draws on her experience as a researcher and educator at the Department of Political and Economic Studies (University of Helsinki), where she gained her Ph.D. in Development Studies (2013). Before her appointment to the Finnish Development Policy Committee, she worked as a researcher in the European Union research programme at the Finnish Institute of International Affairs (FIIA).

Jari Lanki

Jari Lanki is a PhD student at the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Helsinki. He has also taught for several years courses in Development Studies at the Helsinki Open University, including on development policy and aid. Lanki was one of the co-editors for the first Finnish-language textbook on Development Studies.

Notes

1 Finland joined the United Nations in 1955 and established its first section for Development aid (Finnida) under the Ministry for Foreign Affairs ten years later (Koponen et al., Citation2012).

2 Although Finnish policy documents consistently use the term ’development cooperation’ in place of ‘development aid/development assistance’, we will use the term ‘development aid/assistance’ in line with the OECD/DAC definition. The term ‘development policy’ has been in use since 2004 in the official documents in Finland. In practice, it is often used in unison with ‘development cooperation’ although it also refers to the declared aim to take into account the effects of all donor-country policies on developing countries (Policy Coherence for Development). Thus, development policy is seen to encompass the guidance of development aid and governance of other policy sectors towards development goals. In this article, we use the term development policy when referring to the overall policy but focus our analysis on the politics of aid.

3 In addition, for instance, the introduction of the human rights-based approach to development (MFA, Citation2012) could possibly also be seen as a second order change. In the absence of previous academic literature on the subject and with the first MFA evaluation process on this approach just starting in 2022, we leave this as a topic for further research.

4 The proportions of ‘highly important’ have varied between 28–48 per cent and of ‘fairly important’ between 41 and 53 per cent between 2006 and 2020 (Taloustutkimus 2022: compilation of responses).

References

- List of interviewees

- Biaudet, Eva (MP, Swedish People’s Party), online-interview February 22, 2022.

- Hetemäki, Martti (Former Head of cabinet, Ministry for Finance, online-interview March 30, 2022.

- Kiljunen, Kimmo (MP, SDP, vice-chair Finnish Development Policy Committee), online-interview February 7, 2022.

- Lappalainen, Timo (Former Director of NGDO platform KEPA 2005 -2018), Helsinki, November 18 2021.

- Laukko, Helena (Executive Director, Finnish UN league), Helsinki, October 28 2022.

- Majanen, Pertti (Former Finnish Ambassador, MFA), online-interview, April 11 2022.

- Paloniemi, Aila (Former MP 2003-2019, Center Party and Chair of the Development Policy Committee 2016-2019), online-interview, January 31, 2022.

- Puustinen, Pekka (Former Head of Department, Development Policy, MFA), online-interview June 28 2022.

- Sundman, Folke (Former Director of NGDO platform KEPA 1985–2003 and Special advisor to the Minister of Foreign Affairs), Helsinki, November 26 2022.

- Toivakka, Lenita (Former Minister of Development Cooperation and MP, National Coalition Party), online-interview March 22 2002.

- Virkkunen, Suvi (Former Team leader, Development Results/Knowledge management, MFA), online-interview February 3 2022.

- Antola, E., 1978, ‘The evolution of official Finnish development Policy’, Cooperation and Conflict, Vol. 13, No. 4, pp. 231–241.

- A Better Finland: Centre Party Elections Platform, 2015, Centre Party, https://keskusta.fi/politiikkamme/ohjelmia-ja-linjauksia/vaaliohjelmia/ (accessed 17 November 2021).

- Dang, H., S. Knack and F. H. Rogers, 2013, ‘International aid and financial crises in donor countries’, European Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 32, pp. 232–250.

- Delputte, S., S. Lannoo, J. Orbie and J. Verschaeve, 2016, ‘Europeanisation of aid budgets: Nothing is as it seems’, European Politics and Society, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 74–89.

- de Wilde, P., A. Leupold and H. Schmidtke, 2015, ‘Introduction: the differentiated politicisation of European governance’, West European Politics, Vol. 39, No. 1, pp. 3–22.

- Elgström, O., 2017, ‘‘Norm advocacy networks: Nordic and like-minded countries in EU gender and development Policy’, Cooperation and Conflict, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 224–240.

- Elgström, O. and S. Delputte, 2015, ‘‘An end to nordic exceptionalism?’ Europeanisation and nordic development Policies’, European Politics and Society, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 28–41.

- Europe Sustainable Development Report, 2021, https://www.sdgindex.org/reports/europe-sustainable-development-report-2021/(accessed 31 January 2022).

- Evaluation, 2015, Finland’s Development Policy Programmes from a Results-Based Management Point of View 2003-2013, Helsinki : Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- Financial Affairs Committee of Parliament, 2015, Committee Statement on Government Budget 2016, Valiokunnan mietintö VaVM 16/2015 vp.

- Finnfund Act 291/79, 1979, Finnfund. https://www.finnfund.fi/en/finnfund_act/ (accessed 12 March 2022).

- Foreign Affairs Committee of Parliament, 2015, Committee Statement to Financial Committee on Government budget, Valiokunnan lausunto UaVL 2/2015 vp.

- Foreign Affairs Committee of Parliament, 2022, Committee Report on Development Policy 2021, Valiokunnan mietintö UaVM 1/2022 vp─ VNS 5/2021 vp.

- The Greens Elections Platform, 2015, Puolueohjelma 2015 “Kohti Kestävää yhteiskuntaa 2015-2019, ‘The Greens’. https://www.vihreat.fi/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Poliittinen_ohjelma2014.pdf] (accessed 12 December 2021).

- Hackenesh, C., J. Bergmann and J. Orbie, 2021, ‘Development policy under fire? The politicization of European external Relations’, Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 59, No. 1, pp. 3–19.

- Hall, P., 1993, ‘Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: The case of economic policymaking in Britain’, Comparative Politics, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 275–296.

- Janus, H., S. Klingebiel and S. Paulo, 2015, ‘Beyond aid: A conceptual perspective on the transformation of development cooperation’, Journal of International Development, Vol. 27, pp. 155–169.

- Kokoomuksen periaateohjelma, 2018, ‘Programme of Principles’, National Coalition Party, https://www.fsd.tuni.fi/pohtiva/ohjelmalistat/KOK/981 (accessed 14 April 2022).

- Kokoomuksen strateginen vaaliohjelma, 2015, ‘National Coalition Party: Strategic elections platform’, National Coalition Party. file:///C:/Users/um51674/ Downloads/Kokoomuksen%20strateginen %20hallitusohjelma.pdf (accessed 17 November 2021).

- Kokoomuksen vaaliohjelma, 2011. National Coalition Party Elections Platform, https://www.fsd.tuni.fi/pohtiva/ohjelmalistat/KOK/106?start_year = 1880&end_year = 2020&type1 = vaaliohjelma&type5 = tavoiteohjelma&party1 = PARLIMENTARY&language1 = FI&language2 = SV&stext = (accessed 15 January 2021)

- Koponen, J. and L. Siitonen, 2005, Finland: Aid and identity, in P. Hoebink and O. Stokke, ed, Perspectives on European Development Co-Operation: Policy and Performance of Individual Donor Countries and the EU, London: Routledge, pp. 215–241.

- Koponen, J., M. Suoheimo, S. Rugumamu, S. Sharma and J. Kanner, 2012, Finnish Value-Added: Boon or Bane to aid Effectiveness?, Helsinki: Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- Lancaster, C., 2007, Foreign Aid: Diplomacy, Development, Domestic Politics, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- The Level and Quality of Finland’s Development Cooperation: Final Report, 2003, Kehitysyhteistyön tason ja laadun selvitysryhmä: loppuraportti, Helsinki: Ulkoministeriö.

- Mawdsley, E., L. Savage and Sung-Mi Kim, 2014, “A ‘post-aid world'? Paradigm shift in foreign aid and development cooperation at the 2011 Busan High Level Forum’, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 180, No. 1, pp. 27–38.

- MFA, 1993, Finland’s Development Co-operation in the 1990s, Helsinki: Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- MFA, 1996, Decision-in-principle on Finland’s Development Co-operation, Helsinki: Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- MFA, 1998, Finland’s Policy on Relations with Developing Countries, Helsinki: Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- MFA, 2001, Operationalization of Development Policy Objectives in Finland’s International Development Cooperation. Government Decision-in-Principle, Helsinki: Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- MFA, 2004, Development Policy: Government Resolution, Helsinki: Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- MFA, 2007, Development Policy Programme 2007: Towards a Sustainable and Just World Community Government Decision-in-Principle, Helsinki: Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- MFA, 2012, Development Policy Programme 2012, Government Decision-in-Principle, Helsinki: Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- MFA, 2015, Finland’s Development Policy Programmes from a Results-Based Management Point of View 2003-2013, Evaluation 1/2015, Helsinki: Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- MFA, 2016, Government Report on Development Policy: One World, Common Future - Toward Sustainable Development, Helsinki: Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- MFA, 2019, Evaluation on Knowledge Management: “How do we Learn, Manage and Make Decisions in Finland’s Development Policy and Cooperation”, MFA, https://um.fi/development-cooperation-evaluation-reports-comprehensive-evaluations/-/asset_publisher/nBPgGHSLrA13/content/evaluointi-tietojohtamisesta-miten-opimme-johdamme-ja-teemme-paatoksia-suomen-kehityspolitiikassa-ja-yhteistyossa-/384998 (accessed: 14 August 2021).

- MFA, 2021, ‘Report on Development Policy across Parliamentary Terms’. MFA, https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/163218 (accessed 5 June 2021).