ABSTRACT

What makes a piece of research decolonial? Do participatory or co-creative approaches make research participatory and co-creative? These reflections are raised in this article, which looks back at methodological choices made and adapted during a three-year study with riverside communities in the Amazon Forest, in Ecuador and Brazil. Originally designed as grounded research, the project was seriously impacted by restrictions imposed by the global Covid-19 pandemic and, in addition in the Brazilian case, by political issues arising during the 2022 national presidential elections.

This article discusses how these unexpected limitations influenced the fieldwork approach and the resulting answers will be presented as a pedagogy of listening, inspired by the work of Paulo Freire. The recognition and experience of limitations triggered a reflection about disruptive theoretical frameworks and methods. Instead of advocating one precise method, this article advances the relevance of a trans-methodological approach that allows the emergence of new – and/or disruptive – knowledge.

Introduction

At the end of 2019, I started to research how digital media was being used by young members of Amazon riverside communities to express their views of development for their region. It involved advancing studies begun in 2015 with communities living within the Tapajós-Arapiuns Extractive Reserve, in Pará, Brazil (Suzina, Citation2018), and working for the first time with the Indigenous Kichwa People of Sarayaku, in Pastaza, Ecuador. Initially inspired by decolonial methodologies (Castro Lara, Citation2024; Costa Araújo and Maldonado, Citation2023; Tuhiwai Smith, Citation1999), the research had been designed to be carried out from the ground, with field work opening the second semester of the project using participatory methodologies and returning to the communities to discuss and review analyses prior to concluding the project.

These plans were frustrated. The complete first funded year was affected by mobility restrictions imposed by the global Covid-19 pandemic. The Brazilian fieldwork was further limited by political tensions accentuated by the 2022 national presidential elections. These coincided with the moment when travel to the territory became possible again. Would it still be possible to get close to any position that could be called decolonial or participatory?

This article describes the journey of methodological adaptations, reflexivity and learning during the research process from 2020 to 2023. Local perspectives of development observed in the field may be cited briefly and only when relevant for contextualizing reflections on the methods; they are not discussed in this text but can be found elsewhere (Suzina, Citation2023a; Citation2023b). Analysing the adaptations made to cope with the consecutive and unexpected limitations enables questioning if the definition of a method and/or the use of a framework alone can make a research project decolonial or participatory. In doing so, this paper contributes, empirically, to question the presumption of universal benefit of methods labelled as disruptive and to confirm the need of practical transformation to turn labels as transparency (Reyes, Citation2018), decoloniality (Castro Lara, Citation2024) or positionality (Gani and Khan, Citation2024) effectively reparative. Theoretically, it explores the notion of listening (Manyozo, Citation2016) and its role in knowledge production and circulation under a decolonial frame.

I argue that the positionality of the researcher is a constant in the research process, independent of the chosen method and self-declarations. This article therefore joins the conversations about research experiences where an outsider researcher (Tuhiwai Smith, Citation1999) intends to build a dialogical and liberating (Freire, Citation2017) process with the field, assessing the accompanying practical challenges. In association with a pedagogy of listening, the identification of positionalities requires an exercise of reflexivity that goes beyond performative statements (Gani and Khan, Citation2024) to further recognize knowledges and break hierarquies.

This article also questions claims of generalization or scaling up as a core measurement of scientific validity. When effective, decolonial and participatory approaches allow to find the unique dialogues that recognize the peculiarities of relationships and circumstances, which can be of even more value in the field of development and social change. They push trans-methodological frameworks (Maldonado, Citation2019) based on attentive listening, leading to strategies as diverse as the nature and the manifestation of social issues.

In this article, the response to the identified limitations to physically reaching the field took the form of a framework that derived three steps towards what will be described as a pedagogy of listening. They were a ground-framed literature review, joint decisions on sampling and interviewing choices, and open interviews. These steps are presented as one possible response to methodological challenges that can emerge within decolonial guidelines. They are not a model to follow. From a trans-methodological perspective, they are described as indicators that approaches must vary from one project to another. Likewise, in direct opposition to generalizations and canons, they suggest that a single research project is not the final word about anything and looking for this jeopardizes the very possibility of knowledge to support societies’ welfare.

Despite the richness of my experiences with the above-mentioned communities and their peoples and the results obtained in this research, I argue that I cannot speak about decolonization or knowledge co-creation, based on limitations regarding the researcher's previous background, time spent together, possibilities and responsibilities of co-authoring analysis, methodological frameworks and expectations from both sides. I claim that decolonizing or co-creating involves learning with, acknowledging that ‘differently positioned people have different experience, history and social knowledge derived from that positioning’ (Young, Citation2000: 136), and adopting uncomfortable attitudes.

The humility of positioning western knowledge in the place of listening embeds the radicality of allowing ‘other knowledges’ to inform the scientific process. Whilst the latter is framed within a western logic (what is considered as result or impact, for instance), I understand that it is very difficult to talk about decolonization and co-creation. This critical and reflexive consideration aims to preserve a meaningful purpose to the notions of any disruptive approach in science, avoiding their degradation into buzzwords.

The article follows with an introduction to the notion of the pedagogy of listening and how it informed the trifold research methodology conducted with Amazon riverside communities. The three methodological steps will then be described in detail. This is followed by a discussion about the use and utility of labels in research, finally leading to some conclusions and lessons learned.

The pedagogy of listening as a trans-methodological attribute

The development of and the increasing debate about alternative and critical frameworks, such as decolonial approaches or participatory and co-creative methods, reveals a concern and some level of engagement among scholars about the need to introduce or expand more inclusive and diverse practices in academia (Castro Lara, Citation2024; Fals Borda, Citation1985; Gani and Khan, Citation2024; Reyes, Citation2018; Segovia, Citation2023; Tuhiwai Smith, Citation1999), or to even further refund science completely (Fornet-Betancourt, Citation2001). Fields related to development and social change have even higher expectations, considering the association between the construction of knowledge and empirical applications aimed at reducing inequalities and supporting empowerment and transformation locally and globally (Herrera-Huérfano et al., Citation2023; Noske-Turner, Citation2023).

However, the great trick of colonialism, and the coloniality that accompanies it, is that it built a system of knowledge and a capacity to define ‘epistemic “natural” principles’ (Mignolo, Citation2007: 70, inverted commas in the original) to justify some realities and erase others. This is why ‘the Western has disciplines while the Eastern has cultures that are studied by the Western disciplines’ (idem: 60). The pluriverse (Escobar, Citation2020), that can be considered as opposite to colonialism, ‘seeks to recognize and interpret all the realities that present alternatives to what is called development, economic growth and neoliberalism’ (Herrera-Huérfano et al., Citation2023: 6). The decolonial place is the pluriverse, where diversity tops universality, this core feature of colonial Western modernity.

Thus it is important to consider what kinds of methodologies can be considered as decolonial in the sense of leading to the recognition of that diversity of realities on their own terms. The emergent ‘trans-methodology’ (Maldonado, Citation2019; Costa Araújo and Maldonado, Citation2023) advances an approach to research design that responds to such concerns. It proposes liberating rigour from the ties of globally consecrated formats and associating it with highly developed skills in reading and articulating context with refined research questions.

The trans-methodology as a disruptive process

The trans-methodological perspective emerged in the 1990s in discussions about communication epistemology in the School of Communication and Arts, at the University of São Paulo, Brazil. Its configuration draws on theoretical and historical investigations into the constitution of critical thinking in Latin America. In this context, participatory research must be recognized as a turning point in studies of communication, development and social change (Tufte, Citation2017). One of its most recognized authors, Orlando Fals-Borda formulated the Participatory-Action Research (PAR) out of what Jair Vega-Casanova defines as a disenchantment from institutions (Vega Casanova, Citation2021), including academia. Fals-Borda pleaded for a deep association between knowledge and popular power (Fals Borda, Citation1985) while emphasizing academic voice features in distinction to those of social actors, as observed in his book Historia Doble de la Costa (Fals Borda, Citation2002).

The trans-methodology recognizes this popular source to liberate the researcher to adopt a rigorous and yet creative composition of methods that adapts to contexts as well as to exigences posed by research questions. As summarized by Andrielle C.M.M. Guilherme (Citation2022), the trans-methodology calls for an ‘ecological scientific action’ (42) that associates knowledge production with good living principles – referring to traditional Andean philosophies (Contreras Baspinero, Citation2021). This is where academic rigour moves from solely validating knowledge that exclusively fits the dominant paradigm to considering other forms of knowledge embedded very meaningfully in specific contexts – and that can potentially challenge the dominant paradigm.

Alberto Efendy Maldonado (Citation2019) talks about a ‘trans-methodological thought’ that drives the choice of methods and gives an artisanal character to the scientific work without losing academic rigour. It is artisanal because listening to the evidence – the reality, the voice of social actors – leads to specific methodological frameworks that differ in part or completely from one research to another. It is rigorous because a mastery of many different skills is required to establish a meaningful dialogue, manage one own's flaws and come up with a relevant approach for the advancement of knowledge.

For several decades, feminist and indigenous research have been highlighting ‘that “problems” and “solutions” cannot be the same everywhere’ (Segovia, Citation2023: 148). They push the notion of trans-methodology and challenge the idea of disruption itself. In science and technology, disruption is generally seen as the capacity to overcome existing knowledge, ‘rendering it obsolete, and propelling science and technology in new directions’ (Park et al. Citation2023: 139). Even principles of transparency applied to qualitative research look to make their results more ‘valid’ being a synonym for generalizable (Reyes, Citation2018). The decolonial claim moves away from this validating premise of scaling up. The emphasis lays down on the method and how it allows bottom-up knowledge to influence research outcomes.

In all community approaches process – that is, methodology and method – is highly important. In many projects the process is far more important than the outcome. Processes are expected to be respectful, to enable people, to heal and to educate. They are expected to lead one small step further towards self-determination. (Tuhiwai Smith, Citation1999: 127–128)

Listening as a disruptive attribute

For Milton Santos, ‘to decolonize is about looking at the world with one own's eyes and thinking about it from one's own point of view’ (quoted in Tendler, Citation2006). In a research context, this highlights the relevance of allowing the emergence of bottom-up perspectives, recognizing the knowledge already in place in the fields approached (Young, Citation2000). Just as European colonizers did not ‘discover’ new territories, researchers do not discover things or ideas that already exist supposedly lacking a western-driven scientific formulation. As defined by Linda Tuhiwai Smith (above), the research process is an encounter where knowledge is advanced as part of the self-determination of the communities involved.

Nonetheless, Santos’ definition also delineates the existence of the researcher's positionality as someone who arrives in the field with their history – in my case, that of a Latin-American, non-Amazonian, non-indigenous woman predominantly educated within western-inspired systems. This perspective reaffirms that the researcher subjectivity is a relevant and undeniable part of the process, for good and for bad. Moving aside the idea of disruption as overcoming previous knowledge and of research as a way to uncover the unknown, the trans-methodology, as a critical decolonial attitude, seems therefore to be essentially related to the ability to listen.

Listening is considered as a ‘political act’ for its capacity of ‘disrupting, challenging and dismantling’ hierarchies of power relationships (Chandola, Citation2020). It implies engaging levels of recognition (Honneth, Citation2011) that define social validated existence. Inspired by Paulo Freire's work, Linje Manyozo (Citation2016) has already employed this notion to discuss the role of listening in participatory development projects. His ‘major contention is that as development practitioners, we need to build our abilities and capacities to practise all the three forms of listening if we are to work with others in designing and implementing policies that improve lives and communities’ (955). The three forms formulated by Manyozo are ‘(a) listening to evidence; (b) listening to ourselves and (c) listening as a form of speaking’ (idem). The premise highlighted by Manyozo of the development practice looking to improve living conditions relates well to the decolonial agenda as its research focus has identical objectives.

Both in Manyozo's trifold listening concept (above) and in the one that will be described here, listening is rather a relationship where the development practitioner, in Manyozo's work, and the researcher, in the present reflection, listen actively to what is said by the other and to what they, development practitioner and researcher, are actually saying themselves. It is a state of permanent caring awareness.

In her research about indigenous narratives in the Brazilian Northeast region, Guilherme (Citation2022) found in trans-methodology a reference to elaborating a methodological framework based in the dialogue with local indigenous practices. She called it catografia, in reference to indigenous collection practices in Pindorama, the name of the Brazilian territory prior to the arrival of western colonizers – catar, in Portuguese, means ‘to collect’. Her awarded 2023 doctoral study,Footnote1 embraces the objective of making sense of research process findings whilst in constant exchange with the field.

Catografia – as well as Trans-methodology, in my reading – is a proposed approach that aims to bring method and situation closer together; an encounter that, according to Martín-Barbero (1997), forces us to rethink not only the boundaries between disciplines and practices, but also the meaning of the questions themselves: the (theoretical) places of entry into the problems and the plot of (political) ambiguities that involve and displace the exits. (Guilherme, Citation2022: 42)

Listening with disposition to review practices

Regarding listening to the other, Manyozo (Citation2016) highlights that, for Freire, ‘listening does not just imply keeping quiet when someone is speaking’ (958), it is about a virtue and practice of tolerance (955), to which I add, in the research context, the virtue and practice of patience. This overall combination breaks the possibility of stability. In this configuration, the research objective, at least in the development and social change fields, is not to find the newest or the strongest explicative concept or normative principle to define a phenomenon, but to adopt the discipline of following the change that humanity and societies are made of. As underlined in the epistemology of coordination (Whyte, Citation2020), change is the stable element and, consequently, the knowledge about the world must evolve accordingly. The only way to capture how changes flourish or are subject to control is listening with tolerance and patience, moving the focus of knowledge production from the formulation or maintenance of postulates to a permanent dialogue with realities.

In his reflections about the centrality of questions with Freire, Antonio Faundez affirms that the relevance of a research cannot be observed ‘in the answers [findings], because the answers are, with no doubt, as provisory as the questions’ (Freire and Faundez, Citation2018 [Citation1985]: 75). For them, the very meaning of knowledge production is about asking the right questions, which requires paying attention to the reality or phenomenon under scrutiny and listening to the inputs coming from it. The ‘context blindless’ (Berger, Citation2022), which can be correlated with the deafness to evidence in Manyozo's conceptualization (2016), stops researchers from advancing with meaningful knowledge. It drives wrong assumptions, based on outdated, biased information or experience, or it can promote ignorance disguised as full knowledge.

Studying communication dynamics in communities in the Amazon region, Sandro Adalberto Colferai and Fernanda Chocron Miranda talk about ‘cartographic wonderings’ (Colferai and Chocron Miranda, Citation2016) and ‘moving cartographies’ (Chocron Miranda et al., Citation2016) to designate a deep empirical observation and a methodological approach derived from it. The first comes from the reflections about the way Amazonian populations design different strategies to maintain mobility and integration flowing in cities affected by the rise of rivers. It highlights aspects such as flexibility, innovation and an association between a local engagement – responses to situated issues – with a global horizon – the maintenance of the general flow of a defined city or area.

The corresponding methodological approach poses a challenge to researchers to cope with the creativity and adaptability of these social practices, associating scientific rigour with an active attention to the movement resulting from the interaction between human societies and the equally dynamic surrounding environment. This attitude can only be achieved, according to the authors, with a full awareness of the reality under scrutiny and the position from which the latter is being analysed, i.e. the positionality of the researchers in relation to the study.

Such a claim echoes Manyozo's trifold description of listening (Citation2016). Beyond listening to others, he advocates listening to oneself to recognize one own's flaws but also to stand in solidarity with one own's convictions. Colferai and Chocron (Citation2016) talk about the ‘researcher's existential territory’ (40) that needs to be mobilized to allow the establishment of a meaningful relationship with the ‘existing territory’ (idem) of the research and the production of ‘new territorialities’ (idem) that result from the shared knowledge. This permanent reminder of positionality is a humble yet empowered stand. It combines enough humility to recognize each other's limited knowledges – and the possibility of wrong assumptions that can be reviewed – with an honest conviction of relevant principles.

In the interview that inspired Manyozo's trifold listening definition (2016), Freire openly admits to reconnecting with his own self from 40 years ago while still believing that he is a changed man every new day. For Freire, the curious being was and would be there until his last day on earth, making his belief in the power of questions a stable conviction. Manyozo highlights this reconnection with oneself as a necessary exercise to make sense of one's work.

No matter how decolonial – or participatory- or co-creation- driven the research framework is, every one of its participants comes from somewhere and brings their own social, political, economic and other capitals. These can empower the relationship or become a source of power asymmetries. Listening to oneself helps the researcher to remind themselves of the power being exercised in the relationship and to address any discrepancies. The pedagogy of listening seems therefore to be a core element of the ‘trans-methodology’ (Costa Araújo and Maldonado, Citation2023; Maldonado, Citation2019).

In the case described in this article, the recognition and experience of limitations constituted relevant drivers for the search for alternative frameworks. The arrangements based on the pedagogy of listening involved a relevant ground-framed literature review, joint decisions on sampling and interview choices, and open interviews. They will be described in the next sections.

Using the pedagogy of listening in development research

As previously mentioned, the original methodological framework of this project included a first phase of field work starting in the first months of funding, adopting a grounded approach as one of the main elements to ensure the exercise of a decolonial perspective. There was a clear intention to allow the research process to interfere with the direction of the reflection and its results.

The original research question searched for elements to analyse and discuss how young members of riverside communities in the Amazon region, in Brazil and Ecuador, were or were not using digital resources in their collective dynamics of building political imagination and converting it into a political voice. There was a strong interest in observing how development ideas for the Amazon were elaborated and voiced inside the communities and then voiced by them to the outside world. The research would start with the identification and observation of related practices. This plan was obstructed by restrictions on mobility imposed to try to contain the spread of Covid-19 and, in the Brazilian case, it was further compromised by political tensions in the context of national presidential elections (Pellegrini and Puolakkainen, Citation2022). Mobility and security restrictions on research can constitute an issue in themselves. This article does not focus, however, on these aspects. They are the background that prompted a review of the original methodological framework and raised the question about whether, in these circumstances, it would still be possible to preserve its grounded and participatory orientation.

Under the above-mentioned circumstances, the methodological and analytical framework looked more like any regular research where the fieldwork is conducted around the middle of the process, after the completion of a solid literature review, and the clear statement of questions and hypotheses. The issue of whether there is only one specific kind of research that can be done under the principles of decoloniality was raised. Can a label define the decolonial integrity of any approach? Furthermore, the question was about what kind of methodology could support any research, labelled or not, with a liberating agenda, which I define as an engagement with the improvement of life on the planet, in addition to or beyond the achievement of what academic rankings have been defining as quality.

In short, the questions raised during the exercise of reframing the research project can be summarized as follows:

Is there a methodological setting that can offer a similar grounded research approach in the absence of fieldwork as the study starting point?

Can a label define the integrity of any approach?

Can liberating principles be applied to any kind of research, labelled or not?

What are the consequences for academic rigour and community engagement?

In a reflexive analysis, the next sections will describe the three attitudes that were implemented to cope with the research limitations. The ground-framed literature review was an exercise to establish the reflection parameters for a deep dialogue with the communities. Joint decisions on sampling and interview choices, and open interviews were the two methodological options employed when travelling and field work became possible, which corresponded to the second year of funding. Analysis of ongoing work and projections of next steps were driven by questions 1 and 4 (above). The descriptions and reflections presented below come from notes made during the fieldwork and later, during the systematization of the experience, when questions 2 and 3 (above) emerged more clearly.

Ground-framed literature review

The impossibility of grounding the research in fieldwork from the beginning required an alternative strategy and it came, in part, from what I’m calling a ground-framed literature review. As it was impossible to go in person to the field, the first phase of the research was transformed into an effort to listen as much as possible to the voices of members from the communities through materials that they produced themselves or others produced about them. The objective was to find evidence about the way both communities were trying to create their vision of development and make it visible.

There was awareness that this was a mediated approximation of the field. Materials produced by the communities have specific aims and objectives, whether presenting them to external audiences, defending themselves against externally circulating stories, or elaborating conceptualizations associated with their belief systems. Donor or supporter guidelines also directly influence these productions (Noske-Turner, Citation2023). Where research is done on their territories, the positionality of authors and the research objectives also play a role. The grounded-frame literature review was, then, positioned precisely to identify how a view of development emerged from the different documents, including possible historical and conceptual contradictions.

During this review of documents produced by the communities, that lasted around 10 months, two protest events were identified as common points in the timeline of the two case studies and taken as a pic of visibility (Melucci, Citation1999) that exposed their vision of development and how they defended it when externally challenged. Both events were acts of resistance against outsider extractive enterprises in each of the territories.

In Ecuador, the event took place in 2002 when the Indigenous Kichwa People of Sarayaku resisted the arrival of the CGC oil company in their territory, a land invasion granted by the State of Ecuador and protected by the national army. In Brazil, the event took place in 2009, when 26 communities within and neighbouring the Reserva Extrativista Tapajós-Arapiuns blocked the passage of boats loaded with wood from crossing the river Arapiuns just offshore from the community of São Pedro. Taking both extractive enterprises as threats to the ancestral lands inhabited by these communities and to their relationship model to that territory, the objective became to understand the clash between development visions expressed during those events and how the affected communities elaborated and voiced their stances.

Much material is available about the Indigenous Kichwa People of Sarayaku both produced by themselves (e.g. Sarayaku, Citation2014; Viteri Gualinga, Citation2002) and written about them in academic and journalistic outlets (e.g. Martínez Suárez et al., Citation2019; Martínez, Citation2004). The tentative invasion of their territory by oil companies and their resistance is well documented in the context of their successful legal complaint to the International Court of Human Rights against the State of Ecuador, which took place after the event in 2002. There is also a lot of information about the opposition to their struggle. Starting from the audio-visual production available on Eriberto Gualinga's YouTube channelFootnote2, going through a couple of websites created and managed by the community,Footnote3 and the documents related to the legal case (Chávez et al., Citation2005), it was possible to establish a mediated approximation to the field. Eriberto was also invited and joined one online seminar organized by my research centreFootnote4 (Gualinga Montalvo, Citation2021), which facilitated some direct exchanges. Following procedures to secure permission from the Sarayaku to visit their community in the context of this research provided additional information about their internal organization and decision-making processes.

The access to information related to the case study in Brazil was less straightforward. The event taken as the pic of resistance, in 2009, was organized inside the territory of Reserva Extrativista Tapajós-Arapiuns but mainly concerned a piece of land outside of it, the Gleba Nova Olinda, where locals identified illegal logging taking place and where there was a conflict about the ownership of the land (Neepes/ENSP/Fiocruz, Citation2014; Suzina, Citation2023a; Citation2023b). Many materials about that event were no longer available online – even some that I had identified, but not conserved, during previous research in the region. An alternative solution was deployed. As I was unable to travel, a local research assistant was employed temporarily. This support allowed access to archives that were only available locally as well as a snowball dynamic using references and information identified in the documents gathered by the research assistant (e.g. Moraes de Andrade, Citation2019; Castro Sena, Citation2011).

Such a procedure requires the recognition of the drivers that framed the documents used as evidence, as some of the above-mentioned aspects may lead to bias in the research. Grounding the literature review does not exempt the researcher from establishing a rigorous dialogue with additional resources, including those that may be critical of the original evidence. The ground-framed literature review can be considered as a mid-point to achieving decoloniality. The field is not yet speaking by itself, and the positionality of the researcher is still in place. There is, however, room for such research to escape from colonial frameworks imprinted in previous research and already taken as canons to define situations, peoples and cultures. Given that indigenous and traditional stories have almost all been written by foreigners and colonizers, grounded literature review may allow disruptive knowledge to emerge.

In this research, the restricted literature resource frame tapped almost entirely into locally produced knowledge during the first stage of the research, allowing a distant immersion into the field and clearly impacted on the re-definition of the research topic. The effects of the adaptations suggest that any decolonial, participatory or co-creation research framework can strongly benefit from funded sandpits or similar exercises where research ideas can be discussed with peers and, necessarily, with people involved in or affected by the topic under consideration. Such procedures may allow agency from the field over the very definition of research topics, methodological approaches, and theoretical frameworks. They can support the emergence of meaningful questions, as prescribed by Freire and Faundez (Citation2018 [1985]).

Joint decisions on sampling and interview choices

Once travel became possible, trips to the communities were organized, first to Sarayaku, in Ecuador (2 weeks in April 2022), and later to Santarém, in Brazil (2 weeks in August 2022). Preparations involved series of exchanges with members of both communities to secure the required authorizations and to explain the objectives of the work on site, including definitions of the profiles of community members that could and should be interviewed. Different circumstances in each of the territories dictated these decisions, but there were two principles in common for both cases. The first was that the choice of interviewees should be made jointly by the researcher and the communities. The second was that there would be room for a local snowball process where developments during the initial interviews could lead to the addition of other names to the list of interviewees.

Elaborating on their ‘cartographic wonderings’, Colferai and Chocron Miranda (Citation2016) argue that the very goal of a cartography is indeed to map relationships, because its main focus should be on the encounters that produce imprints and new meanings. Engaging deeply with this understanding and with the principle of trans-methodological thought (Maldonado, Citation2019), the joint decision on sampling allowed those encounters with the field to guide the development of the research and, in the Brazilian case, to find solutions to the security issues that emerged during the sampling process. These options looked for increasing the connection between method and a moving situation.

In the case of Sarayaku, preliminary exchanges before arriving in the community produced profiles of a minimum of 10 community members to be interviewed – meaning here as a defined moment for individual conversation, beyond other exchanges that could occur during the researcher's stay in the community. Those profiles were reviewed, and the list was expanded on arrival in the territory. Information exchanged during the interviews as well as field observations served as indicators of the need to meet a few more community members. The final list of interviewees comprised 13 individual community members plus one with a longstanding partner who is not a Sarayaku member. Some were interviewed on more than one occasion and additional exchanges, outside of formal interviews, involved other community members.

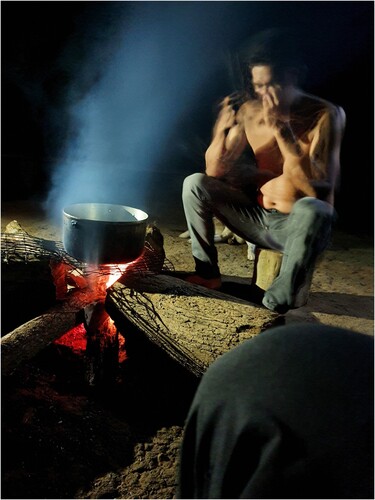

Community dynamics were respected, and exchanges took place determined by each interviewee, which defined the time and place where conversations happened. These configurations were also recorded as data and registered in field notes, as they played a role in setting the conditions for and providing elements of conversation. Frequently, elements of the context were used to describe and/or illustrate ideas evoked during interviews – aspects of these elements were added to the field notes, including drawings and photographs taken using my phone (). The time spent in the community allowed topics to be returned to with discussions either with the same interviewees or with others, as they developed different nuances in different exchanges.

Figure 1: The technology of building houses was frequently mentioned in discussions about community-driven development models. Here, it appears (left) in a child's drawing and in a picture (right). © Ana Cristina Suzina.

The field work in Brazil proved very challenging. After overcoming the travel restrictions, a date for the trip was fixed with the support of the local research assistant. However, new barriers emerged with the 2022 national presidential elections (Pellegrini and Puolakkainen, Citation2022). Conservative actors, legitimized by the aggressive discourse of the then president running for re-election, Jair Bolsonaro, increased tensions. The assassination of the British journalist Dom Philips and the Brazilian indigenist Bruno PereiraFootnote5 in the remote Vale do Javari in the Amazonas region, increased fears. Against this background, community members advised against travelling into the territories. It could be life threatening for a foreign researcher. Additionally, there was a concern that interviews discussing views of development could spark opposition within the communities and become the justification for local violence. Yet again the research framework had to be adapted.

The joint sampling with a smaller group, initiated during the preparations prior to travel and completed once in Santarém, allowed interviews to be conducted in that same city. Members from different communities would come on different days and times, so individuals with opposing perspectives would not meet and not even necessarily know about each other's participation in the research. The field observation and the chain of exchanges were missing, but the impossibility of conducting certain interviews also became relevant data. The very fact that talking about development visions represented a risk spoke for itself and indicated that analyses should contemplate what was said as well as what could not.

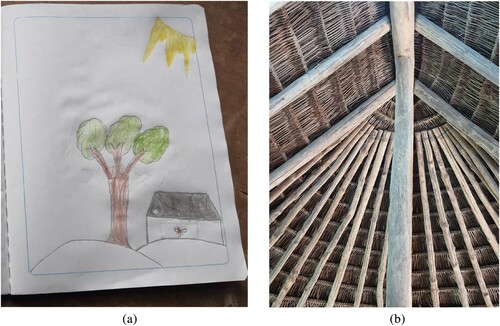

There is a reciprocal relationship in joint sampling. Researchers expect and rely on the openness of the communities to collect the necessary information for analyses. When researchers allow the community to take part in the sampling, they reciprocate this openness with the possibility of the community influencing the direction of the study. The exercise, in this research, suggests that it also contributes to undermining voice hierarchies. Once community members join the sampling process looking to identify who knows something else about certain topics or stories, the community leader is not necessarily the main source of information. During an interview with Abigail Gualinga (abril 2022), identified as a young leader in Sarayaku, she claimed that, if the objective was to understand youth dynamics, the best was to call a wayusa (see below) with young people to have an open conversation with them. Mentions to decision-making process led to the participation in community assemblies to observe it in practice and to listen to their participants (). Horizontal decision making may result in more horizontality in voice raising.

Figure 2: Socialization meeting in the ancestral community of Mawkallakta, Sarayaku, April 2022. © Ana Cristina Suzina.

Joint sampling, including the possibility of onsite snowballing, requires high ethical standards to be maintained. Predefined sampling allows previous evaluation while local decisions may be taken at short notice – something that can happen during any research, but here it is the general rule. The improved trust may lead communities to offer access to sensitive information that, although interesting, can expose the same communities or the research team to undesirable risks, as observed by Victoria Reyes in her analysis about employing transparency in research (Reyes, Citation2018). Working with such configurations, the researcher must have a clear engagement with ethical guidelines and scrupulously apply them in the field.

Open interviews

The pedagogy of listening was completed using non-structured interviews. The exchanges followed the principles of comprehensive interview (Kaufmann, Citation1996) that underlines the importance of establishing a constructive dialogue with those who Jean-Claude Kaufmann calls ‘informants’ (idem, p. 16). The method is founded in the attentive listening of the informants as reflexive actors who are involved in some process by action and by permanent reflection.

The comprehensive approach is based on the conviction that men are not mere agents of structures, but active social producers, and thus the repositories of important knowledge that must be grasped from within, through the bias of each individual's value system; it begins, therefore, by introphatie [a term that can be understood as close to empathy or co-subjectivity]. (Kaufmann, Citation1996: 24, my translation)

Kaufmann's description seem through the decolonial paradigm shows how vocabulary can evolve to recognize not the bias, but the ontological and epistemological frameworks that guide the production and the evolution of knowledge in any group, including that of the researcher that is out there creating questions based on their own framework. The attraction of a comprehensive approach is that it opens the conversation sufficiently to allow the manifestation of these frameworks while keeping the research objectives in sight.

Throughout this research project, every interview was guided by a series of talking points, based on the research objectives and on the review of the communities’ own literature production. However, these talking points evolved during the field work and were presented in a very open way. There was no defined sequence of topics. The kick-off talking point was usually related to the resistance events from 2002 in Sarayaku, and from 2009 in Santarém. Each interviewee was encouraged to divulge where they were and what they recalled from their engagement with those protests or how they unfolded. All the other talking points were integrated in association with aspects raised during the interview and in relation to the place in which each interviewee positioned themselves within the resistance movement. The intention was to follow the symbolic articulations mobilized by each person with whom I spoke that could delineate the relationships established by them individually and collectively to define a view of development and to place it in opposition to any other.

And then it was a moment of sadness because we didn't know what was going to happen to us, to the children, to the grandparents, because they were in lots of different places as well. … We thought that, every gunshot we heard, we thought they had already killed someone. I mean, it was terrible back then, terrible. (Testimony of a Sarayaku woman who was a child during the oil company invasion in 2002, interview, 2022)

Colferai and Chocron Miranda (Citation2016) talk about ‘moving cartographies’ as counterpoint to the process of representing objects. For the authors, the cartography allows the flow of the processes to be followed. Inspired by the work of Jesús Martín-Barbero, they explain that:

The cartography does not aim to isolate the object from its historical connections and from the world; on the contrary, the purpose is to present a design of the network of forces to which it is connected. The cartographer's attention, as it is not focused on a watertight object, can, for this very reason, apprehend movements that are only possible to be observed with open attention. (Colferai and Chocron Miranda, Citation2016: 44)

In Sarayaku, the organization of interviews also followed in part, dynamics already nurtured by the community around the value attached to oral traditions. A couple of the interviews were set-up during the wayusa ritual (), a moment at dawn where families or neighbours or a group of community members meet to drink a specific herbal tea and talk (Suzina, Citation2023b). They exchange and interpret dreams, discuss pressing topics and take binding decisions, constituting a core moment of cohesion and reciprocity. Most of the other interviews took place in spaces related to the individual's activities. Allowing agency to the people I was talking to, so they could choose the place and the moment where and when we spoke, as well as making room to introduce topics or tell stories that they consider relevant to explain themselves, enriched the conversations. It brought elements of reference and descriptions beyond the spoken domain, something that was relevant in the context of a research with a social group for whom natural and transcendental elements have a central role.

The only danger for the Kichwa men [because] we walk, the only danger is, are the snakes, but […] the tigers, the boa, all things are respectful when the man is respectful with the codes of conduct in the jungle. (Tupac Viteri, during wayusa when he associated my adventurous story of walking in the dark in the jungle to reach his house with learning to live with the nature, interview 2022.)

In the context of this research, where I was looking to understand the process from the construction of political imagination to the emergence of political voices regarding development models, the open approach to interviews proved very efficient. The choice made by community members to integrate the interviews within their practices of exchange and decision-making allowed the communicative ethos that permeates community organization to be identified. This finding did not come solely from the representation of objects or the description of practices; it emerged as a preferred feature manifested in the formats chosen by them to facilitate the field work.

The interviews conducted in Santarém were non-structured, but rather framed as they would take place in a neutral place behind closed doors. Some of the participants were so concerned with safety issues that the timetable was organized in such a way that no interviewee would ever cross another. The sole exception was two interviewees who worked in the same organization and were interviewed in its headquarters. We could tap into memories as I had visited the protest site during a 2015 fieldwork visit, but the descriptions were limited to the realm of language. In this case, having the words framed inside rooms together with the impossibility of listening to the contexts speaks loudly for itself. It prevented better access to community processes but allowed the coercion experience that surrounds their social mobilization and political action to come through.

I remember that I would arrive at a place, anywhere, and people would say, ‘look, there it is the boat burner, be careful’ … The local press attacked us hard; they were not capable to listen to us. … This made us be called fake indigenous. (Participant of 2009 protest that did not want to be identified, interview in Santarém, 2022)

Working with open interviews raises questions around rigour, but it should not be confused with a lack of clear objectives or mastery of the process. It requires a permanent analytical attitude from the researcher as initial assumptions need to be confronted with the not necessarily expected evolution of the topic in the field. Linda Tuhiwai Smith advises that ‘[i]dealistic ideas about community collaboration and active participation need to be tempered with realistic assessments of a community's resources and capabilities, even if there is enthusiasm and goodwill’ (1999: 140).

This option makes the researcher reflect permanently about the pertinence and quality of their questions in relation to the depth of reflection expected from the study. In the experience of this research, comprehensive interviews did not change the research objects but did lead to examinations of them from perspectives that were absent at the study outset. Far from trying to ponder the value of this research, this observation underlines how what is usually called rigour may be hiding the dominance of the perspective of the researcher over that from the field. This is the direct opposite of what decolonial frameworks, participatory and co-creative methods aim to achieve.

Lessons and conclusion: will it be different if I give it another name?

In Silvio Tendler's documentary (2006), Milton Santos reflects that it is difficult to be an intellectual because listening and specifically listening with ease to criticism is not part of the national culture. Santos is describing the challenges of being a black man and an intellectual in Brazil, but his observations can be generalized with contextual nuances. The search for alternative and critical frameworks, such as decolonial approaches or participatory and co-creative methods, reveals a certain awareness of this condition, as researchers look for concepts and methods that leave more room for dialogue and bottom-up participation. This lively debate is relevant as it allows the incorporation of different topics into the research agenda, but it also comes with the risk of making notions and concepts banal.

Raul Fornet Bettancourt (2001) expresses a concern about the way knowledge is incorporated into the dominant scientific realm. He criticizes the persistent colonial procedures that serve as legitimacy gatekeepers to select pieces of knowledge that bend enough to be incorporated into the dominant science without changing it at all. Decolonial frameworks, participatory and co-creative methods challenge the dominant way of recognizing and producing knowledge and, as already stated, their increased presence must be celebrated for the benefit they can bring to science. The question that the experience from this research raises regards the relationship between labels and a true room for agency for the social actors involved and sites where research takes place. How much of the dominant science frames – or limits – these disruptive approaches? How much are the latter able to challenge the former?

This problem relates to both sides of the equation. Scholars may be concerned with recognition of rigorous and still engaged methods in academia. Tuhiwai Smith (Citation1999), a recognized researcher in decolonial studies, also identifies this concern in indigenous communities.

What researchers may call methodology, for example, Maori researchers in New Zealand call Kaupapa Maori research or Maori-centred research. This form of naming is about bringing to the centre and privileging indigenous values, attitudes and practices rather than disguising them within Westernized labels such as “collaborative research”. (Tuhiwai Smith, Citation1999: 125)

These potentially disruptive frameworks, as well as an initial perception of the idea of listening, can fall in the same trap as the well-known reflections about giving voice to the voiceless, which are indeed important, but have become very problematic (see e.g. Ferron et al., Citation2022). Benjamin Ferron (Ferron, Citation2022) draws attention, among other aspects, to the meaning of operations specifically organized to allow the emergence of these marginalized voices. In this sense, a method cannot be considered fully disruptive if, although recovering once marginalized voices, it still leads to conservative results, where those voices disappear within the scientific narrative or serve to consolidate – or protect – an unjust cognitive system. Decolonizing, allowing participation, co-creating and any other approach oriented to a dialogical process in research is mainly about losing control. In the opening plenary of the 2022 conference of the Association of Internet Research, Nanjala Nyabola insisted that ‘things will need to break in order to decolonize’ and this looks like the perfect description of theoretical and methodological frameworks claiming a disruptive character. Nyabola associated the notion of colonization with extraction and described its opposite, decolonization, as restitution and a restoration of links. These can only be possible with loss of control. In science, porous approaches give power (back) to all research participants and establish links around the production or review of knowledge.

If decolonizing includes restitution, as suggested by Nyabola, although including any social group's claim or perspective within the research agenda can be considered an important step, this cannot be called decolonization. A step toward restitution may involve having members of respective social groups taking part in the academic and scientific debate – if they understand that this is a relevant venue for their claims, aspirations and reflections. While this full restitution is not in place and outsiders like me engage with any group's agenda in research, the decolonial attitude described by Milton Santos seems pertinent and even necessary. It acknowledges the positionality of the researcher and leads them to the second step of listening described by Manyozo (Citation2016), that is listening to oneself, underlining the role of reflexivity. This means a need to admit and exercise positionality, as no one is completely stripped from their position as a western or urban or white researcher, nor its position as the one who controls funds and who is controlled by the kind of results expected, when adopting a method package formulated to be friendly.

This critical perspective is important for the consolidation of these methods as well as for the way they are employed. Their legitimation by the dominant perspective may be questioned because of such porous features, while their justification as disruptive approaches depends on that. Losing control can mean losing the capacity of confirming or not some theory or findings from previous research, which can affect the appreciation of the study. However, imposing strict procedures goes against the principle of pluriverse where diversity is the rule (Escobar, Citation2020).

In this sense, decoloniality is not a theory or a conceptual framework to be applied as a formula. Participatory and co-creative methods also cannot be seen as such. They are not there to be confirmed or identically replicated, but to drive attitudes that will lead to diverse approaches and results. Following the principles of seeking universality or replicability may lead disruptive approaches to repeat the patterns that they are willing to change.

This article reflects upon a path of methodological adaptations imposed by unforeseeable limitations on a research study planned to be as dialogical as possible. Recognizing and experiencing those limitations however proved useful when discussing aspects that can identify disruptive theoretical frameworks and methods, such as some increasingly present in current debates, like decolonization, participation and co-creation.

I began this research with a decolonial intention, holding a mistaken premise that I could only do decolonial research if I spent a lot of time in the field. And that would be enough. My experience confirms that shared time in the field is indeed precious, but what was an unforeseen limitation in the context of this project is the frequent setting for many studies and this should not limit the decolonial exercise. Regardless of going into the field a lot or a little less, in the adaptation exercise that I had to undertake, what I describe as a pedagogy of listening emerges strongly as a determining factor in the decolonial and participatory nature of the research work. The great challenge is to define a set of methods that allows listening to take place and consistently influence the results.

Applying trans-methodology, this may vary from one research project to another. Guilherme (Citation2022) came up with her catografia. Chocron and Colferai (2016) talk about ‘mobile cartographies.’ I have connected with the idea of a pedagogy of listening (Manyozo, Citation2016). The common ground for these examples is the researcher's willingness to make room for the research process (Tuhiwai Smith, Citation1999) and the popular power (Fals Borda, Citation1985) to influence the direction of reflection.

These options must have consequences for the development of the research, including the way knowledge is identified within or elaborated with the community, and validating evidence that comes from non-western frameworks. In my experience, this is where the limitations are imposed by the western academic system, as journal reviewers and editors, for instance, are not familiar with and/or do not see any relevance in disruptive frameworks. If the result of a disruptive method does not bend enough to fit the dominant paradigm, it may be hard to find a channel for discussing it outside the niches where dominant academia understands they belong.

The examples mentioned also go in the opposite direction to scaling up. No matter how inspiring a methodological framework can be – and Guilherme's and Chocron and Colferai's frameworks indeed inspired me – there is no decolonial method or participatory method that should be taken as a beacon and reference for formatting searches per se. Under the trans-methodological premise, ‘approaching, observing, recognizing, excluding, selecting, recording, organizing, systematizing and experimenting are relevant methodological procedures’ (Maldonado, Citation2011: 292). Engaging with these procedures may lead to different frameworks that do not necessarily apply elsewhere. In this sense, as much as decolonization is about science, trans-methodology is predominantly about the attitude.

Understanding the decolonial shift as a concern regarding the way researchers approach the diversity of phenomena and processes, while recognizing the colonial traces from the professional and personal positionality, the attitude adopted throughout this research was what is described in this article as a pedagogy of listening. It took the form of a trifold procedure, including a ground-framed literature review, joint decisions on sampling and interviews choice, and open interviews. These procedures are not presented as any kind of model. Their description aims at contributing to the debate of how disruptive theoretical frameworks and methods can produce meaningful results for the field and, potentially, transform the way science is carried out.

LEON_ethical_approval.pdf

Download PDF (113.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2024.2374711

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ana Cristina Suzina

Dr Ana Cristina Suzina is a Lecturer at Loughborough University London. She was trained as a journalist (Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa) and has a PhD in Political and Social Sciences (Université catholique de Louvain). Her research interests include popular and community communication, participation issues, inequalities and power asymmetries, production and circulation of knowledge.

Notes

3 See mainly https://sarayaku.org/

4 The presentation is still available at https://repository.lboro.ac.uk/articles/media/Communication_and_Hope_producing_audiovisual_from_the_perspective_of_indigenous_peoples/14397935

References

- Berger, Eva, 2022, Context Blindness. Digital Technology and the Next Stage of Human Evolution, New York: Peter Lang.

- Castro Lara, Eloina, 2024, Comunicación-Decolonialidad: Emergencia de un pensamiento comunicacional otro, in Ana Cristina Suzina and Jair Vega-Casanova eds,La comunicación popular en Nuestramérica: visiones y horizontes, Bogotá: FES, pp.45–60.

- Castro Sena, Antonio E., 2011, Conflitos Ambientais no Ambito do Zoneamento Ecológico-Economico: O Caso da Gleba Nova Olinda em Santarém – Pará, Manaus: Universidade do Estado do Amazonas.

- Chandola, Tripta, 2020, 'Listening: An Ethnographic Exploration', in T. Chandola, ed, Listening into Others: An Ethnographic Exploration in Govindpuri, Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, pp. 45–60.

- Chávez, G., R. Lara and M. Moreno, 2005, Sarayaku: El Pueblo del Cenit, Quito: FLACSO; CDES.

- Chocron Miranda, Fernanda, Sandro Adalberto Colferai and Maria A. Malcher, 2016, ‘Interações em cidades amazônicas sob a perspectiva da cartografia movente’, Chasqui. Revista Latinoamericana de Comunicación, Vol. 130, pp. 179–197.

- Colferai, Sandro Adalberto and Fernanda Chocron Miranda, 2016, ‘Errâncias cartográficas: mapeamentos subjetivos de caminhos movediços para a pesquisa em Comunicação na Amazônia’, Comunicação & Sociedade, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 25–50.

- Contreras Baspinero, Adalid, 2021, 'Communication and Vivir Bien/Buen Vivir. In the care of our common home', in Suzina Ana Cristina ed,The Evolution of Popular Communication in Latin America. An Epistemology of the South from Media and Communication Studies, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 209–227.

- Costa Araújo, B. C. and Alberto Efendy Maldonado, 2023, ‘A transmetodologia como alternativa epistêmica para diálogo com saberes indígenas tradicionais’, Chasquí. Revista Latinoamericana de Comunicación, Vol. 22, No. 42, pp. 42–54.

- Escobar, Arturo, 2020, Pluriversal Politics: the Real and the Possible, Durham: Duke University Press.

- Fals Borda, Orlando, 1985, Conocimiento y poder popular, Bogotá: Editorial Siglo XXI.

- Fals Borda, Orlando, 2002, Historia Doble de la Costa, (2nd ed). Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

- Ferron, Benjamin, 2022, A dialogue with Paulo Freire: Reflections on the social conditions of hope and the problem of equality of expression, in Ana Cristina Suzina and Thomas Tufte, ed, Freire and the Perseverance of Hope: Exploring Communication and Social Change, Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, pp. 51–56.

- Ferron, Benjamin, Émilie Née and Claire Oger, 2022, Donner la parole aux “sans-voix"? Construction sociale et mise en discours d'un probleme public, Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Fornet-Betancourt, Raul, 2001, La philosophie interculturelle. Penser autrement le monde, Editorial, Desclée de Brouwer: Bilbao.

- Freire, Paulo, 2017, Pedagogia do Oprimido. 63 ed., Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra.

- Freire, Paulo and Antonio Faundez, 2018 [1985], Por una pedagogía de la pregunta: crítica a una educación basada en respuestas a preguntas inexistentes, (3a ed). Buenos Aires: Siglo Veintiuno.

- Gani, Jasmine K. and Rebea M Khan, 2024, ‘Positionality Statements as a Function of Coloniality: Interrogating Reflexive Methodologies’, International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 68, No. 2, pp. 1–13.

- Gualinga Montalvo, Eriberto, 2021, Communication and hope: producing audiovisual from the perspective of indigenous peoples, in Ana Cristina Suzina and Thomas Tufte, ed, Freire and the Perseverance of Hope: Exploring Communication and Social Change, Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, pp. 57–58.

- Guilherme, Andrielle C. M. M, 2022, Comunicadoras indígenas e a de(s)colonização das imagens, Natal: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte.

- Herrera-Huérfano, Eliana, Juan Pedro Caranana and Juana Ochoa Almanza, 2023, 'Dialogue of knowledges in the pluriverse, in Pedro-Caranana Joan, Herrera-Huérfano Eliana and Ochoa Almanza Juana eds,Communicative Justice in the Pluriverse: An International Dialogue, New York: Routledge, pp. 5–31.

- Honneth, Axel, 2011, La sociedad del desprecio, Madrid: Editorial Trotta.

- Kaufmann, Jean-Claude, 1996, L'entretien compréhensif, Paris: Nathan.

- Maldonado, Alberto Efendy, 2011, Pesquisa em comunicação: trilhas históricas, contextualização, pesquisa empírica e pesquisa teórica, in Maldonado Alberto Efendy, Schmidt Alencastro Bruno, Antunes Pereira Carmem Rejane, Reis Pedroso da Silva Dafne, Dalprá Becker Fernanda, Bianchi Graziela, Bonin Jiani Adriana, de Sousa Lacerda Juciano, Machado Aguiar Lisiane, Patta Melão Maria Lúcia, Martins do Rosário Nísia, Foletto Rafael and Sá Barreto Virgínia eds,Metodologias de pesquisa em comunicação: olhares, trilhas e processos, Porto Alegre: Sulina, pp. 277–303.

- Maldonado, Alberto Efendy, 2019, ‘El pensamiento transmetodológico en ciencias de la comunicación/; saberes múltiples, fuentes críticas y configuraciones transformadoras’’, Chasqui. Revista Latinoamericana de Comunicación, Vol. 141, pp. 193–214.

- Manyozo, Linje, 2016, ‘The pedagogy of listening’, Development in Practice, Vol. 26, No. 7, pp. 954–959.

- Martínez, Esperanza, 2004, ‘Mujeres víctimas del petróleo y protagonistas de la resistencia’, Biodiversidad, Vol. April, pp. 31–32.

- Martínez Suárez, Yolanda, Agra Romero and Maria Xosé, 2019, ‘Nuevos sujetos, nuevas narrativas: na Naturaleza y el Pueblo de Sarayaku’, eikasia, Revista de Filosofía, Vol. 89, pp. 231–264.

- Melucci, Alberto, 1999, Teoría de la acción colectiva, in Melucci Alberto ed,Acción colectiva, vida cotidiana y democracia, s.l.: El Colegio de México, pp. 25–54.

- Mignolo, Walter D, 2007, La idea de América Latina: La herida colonial y la opción decolonial, Barcelona: Gedisa.

- Moraes de Andrade, Marcelo, 2019, Organizacao Social na Reserva Extrativista Tapajós-Arapiuns: Sistemas Sociais em Mudanca, Santarém: Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará.

- Neepes/ENSP/Fiocruz, 2014, PA – Na Gleba Nova Olinda e entorno, http://mapadeconflitos.ensp.fiocruz.br/conflito/pa-na-gleba-nova-olinda-e-entorno-povo-borari-camponeses-e-ribeirinhos-lutam-contra-grileiros-madeireiros-e-sojicultores-do-sul-que-buscam-cada-vez-mais-expulsa-los-de-suas-terras-enquanto-agua/.

- Noske-Turner, Jessica, 2023, ‘Communication for social changemaking: A “new spirit” in media and communication for development and social change?’, International Journal of Communication, Vol. 17, pp. 2944–2966.

- Park, Michael, Erin Leahey and Russell J Funk, 2023, ‘Papers and patents are becoming less disruptive overtime’, Nature, Vol. 613, pp. 138–144.

- Pellegrini, S. and M. Puolakkainen, 2022, Election Watch: Political Violence during Brazil's 2022 General Elections, https://acleddata.com/2022/10/17/political-violence-during-the-brazil-general-elections-2022/ [Accessed 23 May 2024].

- Reyes, Victoria, 2018, ‘Three models of transparency in ethnographic research: Naming places, naming people, and sharing data’, Ethnography, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 204–226.

- Sarayaku, Pueblo Originario Kichwa de, 2014, El libro de la vida de Sarayaku para defender nuestro futuro, in Hidalgo-Capitán Antonio Luis, Guillén García Alejandro and Deleg Guazha Nancy eds,Antología del Pensamiento Indigenista Ecuatoriano sobre Sumak Kawsay, Huelva y Cuenca: Fiucuhu, pp. 77–102.

- Segovia, Carlos A., 2023, Ontologies and ecologies of the otherwise, in Eliana Herrera-Huérfano, Juan Pedro Caranana and Juana Ochoa Almanza, ed, Communicative Justice in the Pluriverse, New York and Oxon: Routhledge, pp. 146–161.

- Suzina, Ana Cristina, 2018, Popular media and political asymmetries in the Brazilian democracy in times of digital disruption, Louvain-la-Neuve: Universite catholique de Louvain.

- Suzina, Ana Cristina, 2023a, Uma floresta, um rio e muitas vozes: Comunicação e Ativismos na Comunidade de São Pedro de Arapiuns, na Amazônia Brasileira, in Isabel Babo ed,Comunicação e Ativismos na Comunidade Práticas Comunicacionais, Ativismos e Redes, Porto: Socicom, pp.145–168.

- Suzina, Ana Cristina, 2023b, ‘Towards a circular theory of communication: the case of the Wayusa ritual of the Kichwa Indigenous People of Sarayaku’, Journal of Alternative and Community Media, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 145–168.

- Tendler, Silvio, 2006, Encontro com Milton Santos: o mundo global visto do lado de cá, s.l.: s.n.

- Tufte, Thomas, 2017, Communication and Social Change. A citizen perspective, Cambridge: Polity.

- Tuhiwai Smith, Linda, 1999, Decolonizing Methodologies. Research and Indigenous Peoples, London, New York, Dunedin: Zed Books Ltd; University of Otago Press.

- Vega Casanova, J, 2021, Disenchantment as a path toward autonomy. Orlando Fals Borda, PAR, Communication and Social Change, The evolution of popular communication in Latin America. An epistemology of the south from media and communication studies, Cham: Palgrave, pp.109–128.

- Viteri Gualinga, Carlos, 2002, ‘Visión indígena del desarrollo en la Amazonía’, Polis, Vol. 3, pp. 1–7.

- Whyte, Kyle, 2020, 'Against crisis epistemology', in Hokowhitu Brendan, Moreton-Robinson Aileen, Tuhiwai-Smith Linda, Andersen Chris and Larkin Steve eds,Handbook of Critical Indigenous Studies, s.l.: Routledge, pp.52–64.

- Young, Iris Marion, 2000, Inclusion and Democracy, New York: Oxford University Press.