Abstract

Aims: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) is a well-established and widely used screening instrument. It has been shown that AUDIT has good criterion validity in relation to alcohol abuse and dependence according to DSM-IV, but it has not yet been validated following the introduction of the DSM-5 diagnostic system. The aim of this study was to evaluate concurrent validity for the AUDIT in relation to self-reported DSM-5 severity levels for Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) in a Swedish general population sample.

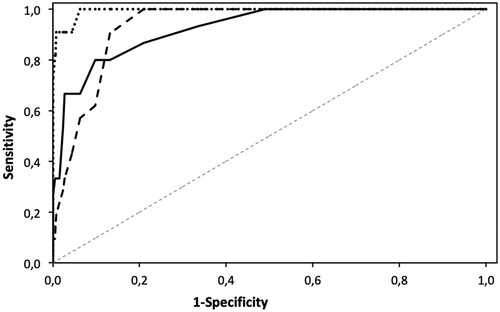

Methods: A postal questionnaire, containing the AUDIT and the 13-item brief DSM-5 AUD diagnostic assessment screener, was sent to a random sample of 1,500 persons drawn from the Swedish population, aged between 17 and 80 years and having a public residence address in Sweden. To evaluate the concurrent validity of AUDIT in relation to DSM-5 severity criteria for AUD, a Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curve analysis was conducted.

Results: Area under the curve (AUROC) showed excellent differentiation between AUD or not, mild (.93), moderate (.92) and severe (.99). Higher individual AUDIT scores were associated with more severe levels of AUD according to the DSM-5 screener. The optimal cutoff scores approximate earlier research on the DSM-IV and were identified as 5, 7 and 13 points, respectively, for mild, moderate and severe AUD.

Conclusions: Our findings indicate that AUDIT is a valid screener for detecting concurrent AUD at three severity levels in the Swedish general population.

Introduction

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) [Citation1] is widely used and defines criteria for Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD). In the current fifth version, DSM-5, 11 criteria for AUD are classified in a unidimensional construct operationalized in three different levels – mild, moderate or severe, depending on the number of criteria met. A 13-item brief DSM-5 self-report AUD diagnostic assessment screener has also been developed by Hagman [Citation2]. In a college student sample of 923 past-year drinkers, aged 18–30, Hagman found that the scale was unidimensional with high internal consistency. Additionally, compared to low consumers people with high alcohol and drug consumption responded affirmatively to a higher number of criteria on the DSM-5 screener. Similar to the original version of DSM-5, the self-report screener defines three severity levels by the number of criteria met, where a mild severity level corresponds to 2 to 3 items, a moderate level 4 to 5 items and a severe level to 6 or more items.

An instrument often used to screen for AUD that has also been used among psychiatric patients in Nordic settings [Citation3,Citation4] is the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) consisting of three items on consumption, three items related to dependence on alcohol and four items indicating alcohol-related harms. AUDIT was developed within the WHO framework, meaning that it is based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) to capture hazardous use, harm and dependence, where the dependence items overlap with DSM. Furthermore, AUDIT is intended as a screener, not a full-blown diagnostic instrument, for the primary health care setting to screen for hazardous and harmful alcohol use [Citation5]. It has been shown to have good validity and reliability in several studies, summarized in several reviews [Citation6–8]. In the original AUDIT, a standard drink was defined as containing 10 grams of alcohol but the definition of a standard drink varies across countries. Higgins-Biddle and Babor [Citation9] adjusted the original AUDIT to US conditions, defining a standard drink as containing 14 grams of alcohol. In the Swedish version of the AUDIT, different beverages containing a standard drink of 12 grams of alcohol are depicted.

To evaluate concurrent validity of AUDIT, several trials have been conducted comparing AUDIT against clinical diagnostic criteria. Babor et al. [Citation10] suggested different AUDIT total score cutoffs indicating AUD severity levels and indications for treatment, where a score of 8–15 corresponds to risky use and should be responded to with simple advice, a score of 16–19 points indicates harmful use, requiring brief counseling and monitoring, and 20 or more points reflect probable dependency and are described as requiring referral for alcohol dependence. Prior research in outpatient clinics has identified varying cutoff levels. Noorbakhsh et al. [Citation11] found a cutoff of 20 to be optimal when screening for DSM-IV alcohol dependence in Iranian psychiatric outpatients. Chang et al. [Citation12] divided patients visiting hospital for a medical examination according to whether they had two or more DSM-5 criteria or not, and found that an optimal AUDIT cutoff of 10 points for men and 5 for women most effectively differentiated between groups. Using a similar design, but outside the clinical setting, Kim et al. [Citation13] found an optimal cutoff of 9 for male and 6 for female college students in predicting any DSM-5 diagnosis. Lundin et al. [Citation14] found an optimal AUDIT cutoff of 6 for both men and women when detecting DSM-IV alcohol dependence among a general population sample aged 20–64 in Stockholm Sweden. The aim of the present study was to psychometrically evaluate the concurrent validity of the AUDIT in detecting the three DSM-5 AUD severity levels, mild, moderate and severe, in a Swedish general population sample.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Data were collected through random selection of 1,500 people, aged 17–80 years (50% women) having a permanent address in Sweden and drawn from an official register (SPAR). Respondents were sent an invitation letter in the spring of 2018 and a postal questionnaire consisting of the Swedish version of the 10-item AUDIT [Citation5,Citation15] and an authorized Swedish translation of the 13-item brief DSM-5 self-report diagnostic assessment screener [Citation2]. The 13-item DSM-5 AUD diagnostic assessment screener is based on the 11 DSM-5 criteria. It includes one additional item each for the tolerance and withdrawal criteria, to account for interpretation differences. Tolerance can namely be interpreted as a) experiencing a lower effect as time goes on or b) drinking more in order to obtain the effect desired, and withdrawal can be interpreted as a) the experience of withdrawal symptoms when not drinking or b) drinking to reduce or eliminate withdrawal symptoms [Citation2]. For each item, participants report the occurrence (yes) or absence (no) within the past year of the criterion described, and the number of yes responses is summarized; for the tolerance and withdrawal criteria, positive responses for one or both relevant items are counted as one. The envelope also contained a stamped response envelope, a letter explaining the study and that their participation are anonymous and voluntary.

A total of 710 individuals responded yielding a response rate of 47.3%, and the response rate among men and the younger age groups was somewhat lower. The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm approved this study (registration number: 2018/184-32).

Statistics

All calculations were made using SPSS 24.0. Three dichotomous variables were created for each of the three severity levels of alcohol use disorders, mild (2–3 criteria), moderate (4–5 criteria) and severe (6 or more criteria). For each dichotomous variable, 0 was coded for those respondents with 0 or 1 DSM-5 criteria and 1 was coded for respondents who fulfilled the requirements for that level. Other respondents were categorized as missing. A Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted calculating area under the curve (AUROC), sensitivity and specificity. Youden’s index was calculated as (sensitivity + specificity)-1. A higher index value indicates an optimum cutoff threshold score, but one should also consider the separate values for sensitivity and specificity [Citation16].

Results

Analysis of the non-responders showed that more women compared to men responded to the questionnaire (χ2 = 7.52, df = 1, p=.006). The mean age among responders (51.0 years, SD = 17.8) was higher than among non-responders (43.2 years, SD = 16.4, t = 8.78, df = 1417 p<.001). Descriptive statistics in relation to the DSM-5 AUD severity levels are shown in . The internal reliability of the DSM-5 AUD diagnostic assessment screener was good (Cronbach’s α = .86). A one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference in AUDIT scores between DSM-5 severity levels (F(3,66) = 187.08, p<.001), but multiple post hoc comparisons showed no difference in AUDIT scores between mild and moderate AUD. This indicates that small differences in alcohol habits may be diagnosed as mild or moderate AUD according to DSM criteria. In , optimal cutoffs for each severity level are shown by a combination of the highest specificity and Youden’s index and were found to be 5, 7 and 13 points for mild, moderate and severe AUD, respectively. depicts ROC curves for each severity level. The AUROCs for the three severity levels were >.90, indicating excellent discrimination between AUD and no AUD at all severity levels. More specifically, AUDIT had the highest AUROC for the highest severity level (.99) and lower for moderate (.92) and mild (.93) levels.

Figure 1. ROC curves for the three DSM-5 severity levels defined by the 13-item DSM-5 AUD diagnostic assessment screener: mild (broken line), moderate (solid) and severe (dotted).

Table 1. Mean and standard deviation of AUDIT scores for each DSM-5 severity levelTable Footnotea.

Table 2. Sensitivity, specificity and Youden’s index for different AUDIT scores when assessing the three DSM-5 severity levelsTable Footnotea,Table Footnoteb.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the concurrent validity of the AUDIT in relation to self-reported DSM-5 AUD severity levels according to the brief DSM-5 diagnostic assessment screener. Results showed that those with the highest level of severity according to DSM-5 had significantly higher average scores on the AUDIT compared to those with lower levels of severity. The AUDIT proved an excellent tool for discriminating between AUD and no AUD at all levels. The optimal AUDIT cutoffs for detecting mild, moderate and severe AUD were in line with previous research that has validated the AUDIT in relation to both DSM-IV and DSM-5 alcohol diagnoses. The results support the concurrent validity of the AUDIT in relation to the brief DSM-5 diagnostic assessment criteria and add support to the construct validity of the DSM-5-based scale. Interestingly, the cutoffs for AUD severity levels identified here were lower than in previous research [Citation10,Citation11], but not directly contradictory.

A primary limitation in the study was the modest response rate, implying a possible problem with selection bias. In fact, more women compared to men responded to the questionnaire, and responders’ age was higher compared to non-responders. Another limitation was that, due to few women admitting to fulfillment of any DSM criteria, it was not feasible to determine gender specific cutoffs. An additional limitation is that DSM-5 criteria were assessed via self-report, not via personal diagnostic interview, as is optimal in studies of criterion validity.

Conclusions

The results presented indicate that AUDIT may serve as an adequately valid screener for detecting different DSM-5 AUD severity levels in the Swedish general population. Further research on the AUDIT-DSM-5 relationship should be undertaken in treatment-seeking samples.

Notes on contributors

HK, PW and AHB conceived the research idea and applied for funding. HK and TE wrote the first manuscript draft, in consultation with PE and AHB regarding background, results analysis and discussion. All authors contributed significantly to continued manuscript drafts, responses to reviewers and the final draft. .

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Hagman BT. Development and psychometric analysis of the brief DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder diagnostic assessment: towards effective diagnosis in college students. Psychol Addict Behav. 2017;31:797–806.

- Karpov B, Joffe G, Aaltonen K, et al. Self-reported treatment adherence among psychiatric in- and outpatients. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72:526–533.

- Sorensen T, Jespersen HSR, Vinberg M, et al. Substance use among Danish psychiatric patients: a cross-sectional study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72:130–136.

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, et al. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804.

- Allen JP, Litten RZ, Fertig JB, et al. A review of research on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:613–619.

- de Meneses-Gaya C, Zuardi AW, Loureiro SR, et al. Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): an updated systematic review of psychometric properties. Psychol Neurosci. 2009;2:83–97.

- Reinert DF, Allen JP. The alcohol use disorders identification test: an update of research findings. Alcoholism Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:185–199.

- Higgins-Biddle JC, Babor TF. A review of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), AUDIT-C, and USAUDIT for screening in the United States: past issues and future directions. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44:578–586.

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, et al. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: guidelines for use in primary health care. 2nd ed. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2001.

- Noorbakhsh S, Shams J, Lofti-Lelahloo R, et al. An empirical study of the cut-off point for the Iranian version of Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Asia Pacific J Med Toxicol. 2018;7:75–78.

- Chang JW, Kim JS, Jung JG, et al. Validity of Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Korean revised version for screening Alcohol Use Disorder according to diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition criteria. Korean J Fam Med. 2016;37:323–328.

- Kim SJ, Kim JS, Kim SS, et al. Usefulness of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Korean revised version in screening for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5th edition alcohol use disorder among college students. Korean J Fam Med. 2018;39:333–339.

- Lundin A, Hallgren M, Balliu N, et al. The use of alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in detecting alcohol use disorder and risk drinking in the general population: validation of AUDIT using schedules for clinical assessment in neuropsychiatry. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:158–165.

- Bergman H, Källmén H. Alcohol use among Swedes and a psychometric evaluation of the alcohol use disorders identification test. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:245–251.

- Akobeng AK. Understanding diagnostic tests 3: receiver operating characteristic curves. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:644–647.